User login

Patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer who had end-of-life discussions with caregivers before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive care in their final days and more likely to get hospice care and to enter hospice earlier, a study of 1,231 patients found.

Nearly half received some kind of aggressive care in their last 30 days (47%), including chemotherapy in the last 14 days (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days (6%), and/or acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%), Dr. Jennifer W. Mack and her associates reported.

Multiple current guidelines recommend starting end-of-life care planning for patients with incurable cancer early in the course of the disease while patients are relatively stable, not when they are acutely deteriorating.

Many physicians in the study postponed the discussion until the final month of life, and many patients didn’t remember or didn’t recognize the end-of-life discussions. Discussions that were documented in charts were not associated with less-aggressive care or greater hospice use, if patients or their surrogates said no end-of-life discussions took place.

Eighty-eight percent of patients in the current study had end-of-life discussions. Twenty-three percent of the discussion were reported by patients or their surrogates in interviews but not documented in records, 17% were documented in medical records but not reported by patients or surrogates, and 48% were both reported and documented.

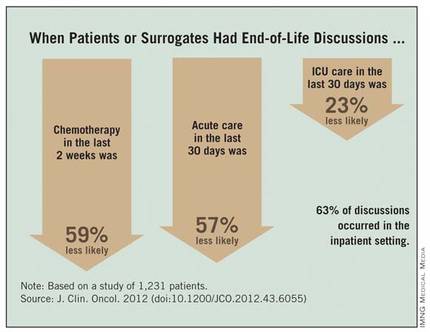

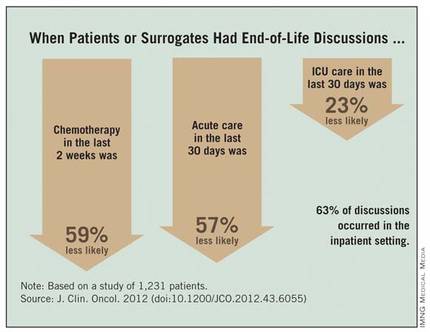

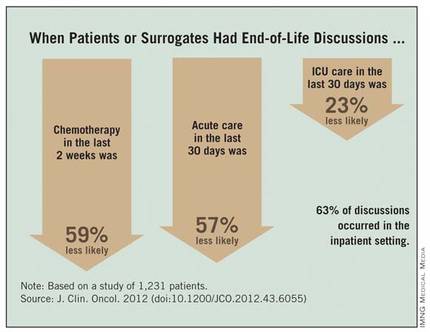

Among the 794 patients with end-of-life discussions documented in medical records, 39% took place in the last 30 days of life, 63% happened in the inpatient setting, and 40% included an oncologist. Fifty-eight percent of patients entered hospice care, which started in the last 7 days of life for 15% of them, reported Dr. Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The study was published online Nov. 13, 2012 by the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055).

Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Patients Followed 15 Months After Diagnosis

Patients whose first end-of-life discussion happened while they were hospitalized were more than twice as likely to get any kind of aggressive care at the end of life and three times more likely to get acute care or ICU care in the last 30 days and to have hospice care start within the last week before death.

Having a medical oncologist present at the first end-of-life discussion increased the odds of having chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life by 48%, decreased the odds of ICU care in the last 30 days by 56%, increased the likelihood of hospice care by 43%, and doubled the chance of hospice care starting in the last 7 days of life. All of these odds ratios were significant after controlling for other factors.

Data came from a larger cohort of 2,155 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer receiving care in HMOs or Veterans Affairs medical centers in five states. All were followed for 15 months after diagnosis in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.

An earlier analysis by the same investigators showed that 87% of the 1,470 patients who died and 41% of the 685 still alive by the end of follow-up had end-of-life care discussions, but oncologists documented end-of-life discussions with only 27% of their patients, suggesting that most discussions were with non-oncologists. Among those who died, documented discussions took place a median of 33 days before death (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:204-10).

"Our previous study on this database found that most physicians do have end-of-life discussions before death, but most occur near the end of life," Dr. Mack said in an interview.

The current study analyzed data for 1,231 of the patients who died but who lived at least 1 month after diagnosis, in order to assess whether the timing of discussions influenced end-of-life care. "Besides the fact that that seems like logical practice, there really wasn’t a clear evidence base that that affects care," she said.

Patients were significantly less likely to say they’d had an end-of-life discussion if they were unmarried, black or non-white Hispanic, or not in an HMO.

Start Talks Closer to Diagnosis

When discussions don’t begin until the last 30 days of life, the end-of-life period usually is already underway, the investigators noted. Physicians should consider moving end-of-life care discussions closer to diagnosis, they suggested, while patients are relatively well and have time to plan for what’s ahead.

"It’s something that any physician can do," but some previous studies report that physicians are reluctant to start end-of-life discussions early because these are emotionally difficult conversations, they worry about taking away hope, and they are concerned about the psychological impact on patients – though there is no clear evidence that it does have psychological consequences for patients, Dr. Mack said.

"It’s a compassionate instinct," she said. "Being in the room with a family when I deliver this kind of news, that emotional impact is right in front of me. I believe there are bigger consequences" from not discussing end-of-life care, such as perpetuating false hopes and asking people to make decisions about what’s ahead without a clear picture of the situation, she added.

The conversation should take place more than once because patient preferences may change over time and patients need time to process the information and their thoughts about it, Dr. Mack said.

Ask Patients What They Hear

Further work is needed on why some documented end-of-life discussions were not reported by patients/surrogates. "Every physician can relate to this, that sometimes we have conversations but they’re not heard or understood by patients," she said. "It reminds me that I need to ask patients what they’re taking away from these conversations and use that to guide me going forward."

That finding echoes two recent large, population-based studies that found many patients with terminal cancer mistakenly think that palliative chemotherapy or radiation will cure their disease.

Some previous studies suggest that patients dying of cancer increasingly are receiving aggressive care at the end of life and that this trend may be modifiable. Cross-sectional studies that assessed one point in time between diagnosis and death have shown that many patients don’t have end-of-life discussions, but these studies probably missed discussions closer to death, Dr. Mack noted.

Other studies have reported an association between having end-of-life discussions and reduced intensity in care. The current study was longitudinal and is one of the first to look at the effects of the timing of these discussions and other factors.

Most patients who realize that they are dying do not want aggressive care, previous studies have shown. Other studies report that less-aggressive end-of-life care is easier on family members and less expensive.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Physicians and American Society of Internal Medicine recommend beginning end-of-life discussions early for patients with incurable cancer.

When investigators conducted secondary analyses that excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites or excluded interviews with patient surrogates, the findings were similar to results of the main analysis.

In the current analysis, 82% of patients had lung cancer, and the rest had colorectal cancer.

Future research on this topic could take many paths, Dr. Mack suggested, including implementing routine early discussions and seeing whether that alters the intensity of final care. Much more could be learned about the quality of discussions between physicians and patients. The current study had no data on discussions led by nurses or social workers or that took place among family members without a medical provider present.

"We’re also interested in looking at a longer trajectory of end-of-life decision making" for patients with incurable cancer – from diagnosis to death, she said.

Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

This is an important study that documents the fact that early discussions about end-of-life care for patients with stage IV cancer are associated with decreased intensity of care at the end of life, and that the timing of the initiation of these discussions is very important and should happen earlier than it does much of the time.

This is not the first study to show that this communication is associated with decreased intensity of care (JAMA 2008;300:1665-73). However, this is an important study because it is the first to document that early discussions are important (prior to the last 30 days of life).

|

|

Moving end-of-life discussions closer to diagnosis definitely is realistic and the way this should occur. However, it is not an "either-or" situation. Early discussions don’t mean that later discussions aren’t necessary and important. Early discussions set the frame and make it easier to have later discussions if/when patients get worse.

There is a need for physicians to improve communication to make sure patients or their surrogates understand end-of-life discussions. Our challenge now is to find successful ways to teach these communication skills to physicians and help physicians implement these discussions in clinical practice. It is not useful to tell physicians to have these discussions if they haven’t been trained to do it well, and we don’t create systems that make it practical and feasible.

When the Obama administration tried to implement a policy of paying physicians to conduct advance care planning on an annual basis through Medicare, Sarah Palin and others used the "death panel" scare tactics to defeat this important effort. We need to change the public discussion to be more aware of the importance of early and regular discussions about advance care planning.

We also need research to figure out how best to implement "earlier discussions" in clinical practice and to identify the long-term consequences of such a practice.

Dr. J. Randall Curtis is director of the University of Washington Palliative Care Center of Excellence and head of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He provided these comments in an interview. Dr. Curtis reported having no financial disclosures.

This is an important study that documents the fact that early discussions about end-of-life care for patients with stage IV cancer are associated with decreased intensity of care at the end of life, and that the timing of the initiation of these discussions is very important and should happen earlier than it does much of the time.

This is not the first study to show that this communication is associated with decreased intensity of care (JAMA 2008;300:1665-73). However, this is an important study because it is the first to document that early discussions are important (prior to the last 30 days of life).

|

|

Moving end-of-life discussions closer to diagnosis definitely is realistic and the way this should occur. However, it is not an "either-or" situation. Early discussions don’t mean that later discussions aren’t necessary and important. Early discussions set the frame and make it easier to have later discussions if/when patients get worse.

There is a need for physicians to improve communication to make sure patients or their surrogates understand end-of-life discussions. Our challenge now is to find successful ways to teach these communication skills to physicians and help physicians implement these discussions in clinical practice. It is not useful to tell physicians to have these discussions if they haven’t been trained to do it well, and we don’t create systems that make it practical and feasible.

When the Obama administration tried to implement a policy of paying physicians to conduct advance care planning on an annual basis through Medicare, Sarah Palin and others used the "death panel" scare tactics to defeat this important effort. We need to change the public discussion to be more aware of the importance of early and regular discussions about advance care planning.

We also need research to figure out how best to implement "earlier discussions" in clinical practice and to identify the long-term consequences of such a practice.

Dr. J. Randall Curtis is director of the University of Washington Palliative Care Center of Excellence and head of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He provided these comments in an interview. Dr. Curtis reported having no financial disclosures.

This is an important study that documents the fact that early discussions about end-of-life care for patients with stage IV cancer are associated with decreased intensity of care at the end of life, and that the timing of the initiation of these discussions is very important and should happen earlier than it does much of the time.

This is not the first study to show that this communication is associated with decreased intensity of care (JAMA 2008;300:1665-73). However, this is an important study because it is the first to document that early discussions are important (prior to the last 30 days of life).

|

|

Moving end-of-life discussions closer to diagnosis definitely is realistic and the way this should occur. However, it is not an "either-or" situation. Early discussions don’t mean that later discussions aren’t necessary and important. Early discussions set the frame and make it easier to have later discussions if/when patients get worse.

There is a need for physicians to improve communication to make sure patients or their surrogates understand end-of-life discussions. Our challenge now is to find successful ways to teach these communication skills to physicians and help physicians implement these discussions in clinical practice. It is not useful to tell physicians to have these discussions if they haven’t been trained to do it well, and we don’t create systems that make it practical and feasible.

When the Obama administration tried to implement a policy of paying physicians to conduct advance care planning on an annual basis through Medicare, Sarah Palin and others used the "death panel" scare tactics to defeat this important effort. We need to change the public discussion to be more aware of the importance of early and regular discussions about advance care planning.

We also need research to figure out how best to implement "earlier discussions" in clinical practice and to identify the long-term consequences of such a practice.

Dr. J. Randall Curtis is director of the University of Washington Palliative Care Center of Excellence and head of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He provided these comments in an interview. Dr. Curtis reported having no financial disclosures.

Patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer who had end-of-life discussions with caregivers before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive care in their final days and more likely to get hospice care and to enter hospice earlier, a study of 1,231 patients found.

Nearly half received some kind of aggressive care in their last 30 days (47%), including chemotherapy in the last 14 days (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days (6%), and/or acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%), Dr. Jennifer W. Mack and her associates reported.

Multiple current guidelines recommend starting end-of-life care planning for patients with incurable cancer early in the course of the disease while patients are relatively stable, not when they are acutely deteriorating.

Many physicians in the study postponed the discussion until the final month of life, and many patients didn’t remember or didn’t recognize the end-of-life discussions. Discussions that were documented in charts were not associated with less-aggressive care or greater hospice use, if patients or their surrogates said no end-of-life discussions took place.

Eighty-eight percent of patients in the current study had end-of-life discussions. Twenty-three percent of the discussion were reported by patients or their surrogates in interviews but not documented in records, 17% were documented in medical records but not reported by patients or surrogates, and 48% were both reported and documented.

Among the 794 patients with end-of-life discussions documented in medical records, 39% took place in the last 30 days of life, 63% happened in the inpatient setting, and 40% included an oncologist. Fifty-eight percent of patients entered hospice care, which started in the last 7 days of life for 15% of them, reported Dr. Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The study was published online Nov. 13, 2012 by the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055).

Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Patients Followed 15 Months After Diagnosis

Patients whose first end-of-life discussion happened while they were hospitalized were more than twice as likely to get any kind of aggressive care at the end of life and three times more likely to get acute care or ICU care in the last 30 days and to have hospice care start within the last week before death.

Having a medical oncologist present at the first end-of-life discussion increased the odds of having chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life by 48%, decreased the odds of ICU care in the last 30 days by 56%, increased the likelihood of hospice care by 43%, and doubled the chance of hospice care starting in the last 7 days of life. All of these odds ratios were significant after controlling for other factors.

Data came from a larger cohort of 2,155 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer receiving care in HMOs or Veterans Affairs medical centers in five states. All were followed for 15 months after diagnosis in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.

An earlier analysis by the same investigators showed that 87% of the 1,470 patients who died and 41% of the 685 still alive by the end of follow-up had end-of-life care discussions, but oncologists documented end-of-life discussions with only 27% of their patients, suggesting that most discussions were with non-oncologists. Among those who died, documented discussions took place a median of 33 days before death (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:204-10).

"Our previous study on this database found that most physicians do have end-of-life discussions before death, but most occur near the end of life," Dr. Mack said in an interview.

The current study analyzed data for 1,231 of the patients who died but who lived at least 1 month after diagnosis, in order to assess whether the timing of discussions influenced end-of-life care. "Besides the fact that that seems like logical practice, there really wasn’t a clear evidence base that that affects care," she said.

Patients were significantly less likely to say they’d had an end-of-life discussion if they were unmarried, black or non-white Hispanic, or not in an HMO.

Start Talks Closer to Diagnosis

When discussions don’t begin until the last 30 days of life, the end-of-life period usually is already underway, the investigators noted. Physicians should consider moving end-of-life care discussions closer to diagnosis, they suggested, while patients are relatively well and have time to plan for what’s ahead.

"It’s something that any physician can do," but some previous studies report that physicians are reluctant to start end-of-life discussions early because these are emotionally difficult conversations, they worry about taking away hope, and they are concerned about the psychological impact on patients – though there is no clear evidence that it does have psychological consequences for patients, Dr. Mack said.

"It’s a compassionate instinct," she said. "Being in the room with a family when I deliver this kind of news, that emotional impact is right in front of me. I believe there are bigger consequences" from not discussing end-of-life care, such as perpetuating false hopes and asking people to make decisions about what’s ahead without a clear picture of the situation, she added.

The conversation should take place more than once because patient preferences may change over time and patients need time to process the information and their thoughts about it, Dr. Mack said.

Ask Patients What They Hear

Further work is needed on why some documented end-of-life discussions were not reported by patients/surrogates. "Every physician can relate to this, that sometimes we have conversations but they’re not heard or understood by patients," she said. "It reminds me that I need to ask patients what they’re taking away from these conversations and use that to guide me going forward."

That finding echoes two recent large, population-based studies that found many patients with terminal cancer mistakenly think that palliative chemotherapy or radiation will cure their disease.

Some previous studies suggest that patients dying of cancer increasingly are receiving aggressive care at the end of life and that this trend may be modifiable. Cross-sectional studies that assessed one point in time between diagnosis and death have shown that many patients don’t have end-of-life discussions, but these studies probably missed discussions closer to death, Dr. Mack noted.

Other studies have reported an association between having end-of-life discussions and reduced intensity in care. The current study was longitudinal and is one of the first to look at the effects of the timing of these discussions and other factors.

Most patients who realize that they are dying do not want aggressive care, previous studies have shown. Other studies report that less-aggressive end-of-life care is easier on family members and less expensive.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Physicians and American Society of Internal Medicine recommend beginning end-of-life discussions early for patients with incurable cancer.

When investigators conducted secondary analyses that excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites or excluded interviews with patient surrogates, the findings were similar to results of the main analysis.

In the current analysis, 82% of patients had lung cancer, and the rest had colorectal cancer.

Future research on this topic could take many paths, Dr. Mack suggested, including implementing routine early discussions and seeing whether that alters the intensity of final care. Much more could be learned about the quality of discussions between physicians and patients. The current study had no data on discussions led by nurses or social workers or that took place among family members without a medical provider present.

"We’re also interested in looking at a longer trajectory of end-of-life decision making" for patients with incurable cancer – from diagnosis to death, she said.

Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer who had end-of-life discussions with caregivers before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive care in their final days and more likely to get hospice care and to enter hospice earlier, a study of 1,231 patients found.

Nearly half received some kind of aggressive care in their last 30 days (47%), including chemotherapy in the last 14 days (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days (6%), and/or acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%), Dr. Jennifer W. Mack and her associates reported.

Multiple current guidelines recommend starting end-of-life care planning for patients with incurable cancer early in the course of the disease while patients are relatively stable, not when they are acutely deteriorating.

Many physicians in the study postponed the discussion until the final month of life, and many patients didn’t remember or didn’t recognize the end-of-life discussions. Discussions that were documented in charts were not associated with less-aggressive care or greater hospice use, if patients or their surrogates said no end-of-life discussions took place.

Eighty-eight percent of patients in the current study had end-of-life discussions. Twenty-three percent of the discussion were reported by patients or their surrogates in interviews but not documented in records, 17% were documented in medical records but not reported by patients or surrogates, and 48% were both reported and documented.

Among the 794 patients with end-of-life discussions documented in medical records, 39% took place in the last 30 days of life, 63% happened in the inpatient setting, and 40% included an oncologist. Fifty-eight percent of patients entered hospice care, which started in the last 7 days of life for 15% of them, reported Dr. Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The study was published online Nov. 13, 2012 by the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055).

Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Patients Followed 15 Months After Diagnosis

Patients whose first end-of-life discussion happened while they were hospitalized were more than twice as likely to get any kind of aggressive care at the end of life and three times more likely to get acute care or ICU care in the last 30 days and to have hospice care start within the last week before death.

Having a medical oncologist present at the first end-of-life discussion increased the odds of having chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life by 48%, decreased the odds of ICU care in the last 30 days by 56%, increased the likelihood of hospice care by 43%, and doubled the chance of hospice care starting in the last 7 days of life. All of these odds ratios were significant after controlling for other factors.

Data came from a larger cohort of 2,155 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer receiving care in HMOs or Veterans Affairs medical centers in five states. All were followed for 15 months after diagnosis in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.

An earlier analysis by the same investigators showed that 87% of the 1,470 patients who died and 41% of the 685 still alive by the end of follow-up had end-of-life care discussions, but oncologists documented end-of-life discussions with only 27% of their patients, suggesting that most discussions were with non-oncologists. Among those who died, documented discussions took place a median of 33 days before death (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:204-10).

"Our previous study on this database found that most physicians do have end-of-life discussions before death, but most occur near the end of life," Dr. Mack said in an interview.

The current study analyzed data for 1,231 of the patients who died but who lived at least 1 month after diagnosis, in order to assess whether the timing of discussions influenced end-of-life care. "Besides the fact that that seems like logical practice, there really wasn’t a clear evidence base that that affects care," she said.

Patients were significantly less likely to say they’d had an end-of-life discussion if they were unmarried, black or non-white Hispanic, or not in an HMO.

Start Talks Closer to Diagnosis

When discussions don’t begin until the last 30 days of life, the end-of-life period usually is already underway, the investigators noted. Physicians should consider moving end-of-life care discussions closer to diagnosis, they suggested, while patients are relatively well and have time to plan for what’s ahead.

"It’s something that any physician can do," but some previous studies report that physicians are reluctant to start end-of-life discussions early because these are emotionally difficult conversations, they worry about taking away hope, and they are concerned about the psychological impact on patients – though there is no clear evidence that it does have psychological consequences for patients, Dr. Mack said.

"It’s a compassionate instinct," she said. "Being in the room with a family when I deliver this kind of news, that emotional impact is right in front of me. I believe there are bigger consequences" from not discussing end-of-life care, such as perpetuating false hopes and asking people to make decisions about what’s ahead without a clear picture of the situation, she added.

The conversation should take place more than once because patient preferences may change over time and patients need time to process the information and their thoughts about it, Dr. Mack said.

Ask Patients What They Hear

Further work is needed on why some documented end-of-life discussions were not reported by patients/surrogates. "Every physician can relate to this, that sometimes we have conversations but they’re not heard or understood by patients," she said. "It reminds me that I need to ask patients what they’re taking away from these conversations and use that to guide me going forward."

That finding echoes two recent large, population-based studies that found many patients with terminal cancer mistakenly think that palliative chemotherapy or radiation will cure their disease.

Some previous studies suggest that patients dying of cancer increasingly are receiving aggressive care at the end of life and that this trend may be modifiable. Cross-sectional studies that assessed one point in time between diagnosis and death have shown that many patients don’t have end-of-life discussions, but these studies probably missed discussions closer to death, Dr. Mack noted.

Other studies have reported an association between having end-of-life discussions and reduced intensity in care. The current study was longitudinal and is one of the first to look at the effects of the timing of these discussions and other factors.

Most patients who realize that they are dying do not want aggressive care, previous studies have shown. Other studies report that less-aggressive end-of-life care is easier on family members and less expensive.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Physicians and American Society of Internal Medicine recommend beginning end-of-life discussions early for patients with incurable cancer.

When investigators conducted secondary analyses that excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites or excluded interviews with patient surrogates, the findings were similar to results of the main analysis.

In the current analysis, 82% of patients had lung cancer, and the rest had colorectal cancer.

Future research on this topic could take many paths, Dr. Mack suggested, including implementing routine early discussions and seeing whether that alters the intensity of final care. Much more could be learned about the quality of discussions between physicians and patients. The current study had no data on discussions led by nurses or social workers or that took place among family members without a medical provider present.

"We’re also interested in looking at a longer trajectory of end-of-life decision making" for patients with incurable cancer – from diagnosis to death, she said.

Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Major Finding: Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or their surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Data Source: This was a longitudinal study of 1,231 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer at HMOs or Veterans Affairs sites in five states.

Disclosures: Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.