User login

Keeping up to date and maintaining currency on developments in medicine are a routine part of medical practice, but the means by which this is accomplished are changing rapidly. Training, maintenance of certification, continuing education, mentoring, and career development will all be transformed in the coming years because of new technology and changing needs of physicians. Traditional learning channels such as print media and in-person courses will give way to options that emphasize ease of access, collaboration with fellow learners, and digitally optimized content.

Education and content delivery

The primary distribution channels for keeping medical professionals current in their specialty will continue to shift away from print publications and expand to digital outlets including podcasts, video, and online access to content.1 Individuals seeking to keep up professionally will increasingly turn to resources that can be found quickly and easily, for example, through voice search. Content that has been optimized to appear quickly and with a clear layout adapted to a wide variety of devices will most likely be consumed at a higher rate than resources from well-established organizations that have not transformed their continuing education content. There is already a growing demand for video and audiocasts accessible via mobile device.2

John D. Buckley, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine and vice chair for education at Indiana University, Indianapolis, sees the transformation of content delivery as a net plus for physicians, with a couple of caveats. He noted, “Whether it is conducting an in-depth literature search, reading/streaming a review lecture, or simply confirming a medical fact, quick access can enhance patient care and advance learning in a manner that meets an individual’s learning style. One potential downside is the risk of unreliable information, so accessing trustworthy sources is essential. Another potential downside is that, while accessing the answer to a very specific question can be done very easily, this might compromise additional learning of related material that used to occur when you had to read an entire book chapter to answer your question. Not only did you answer your question, you learned a lot of other relevant information along the way.”

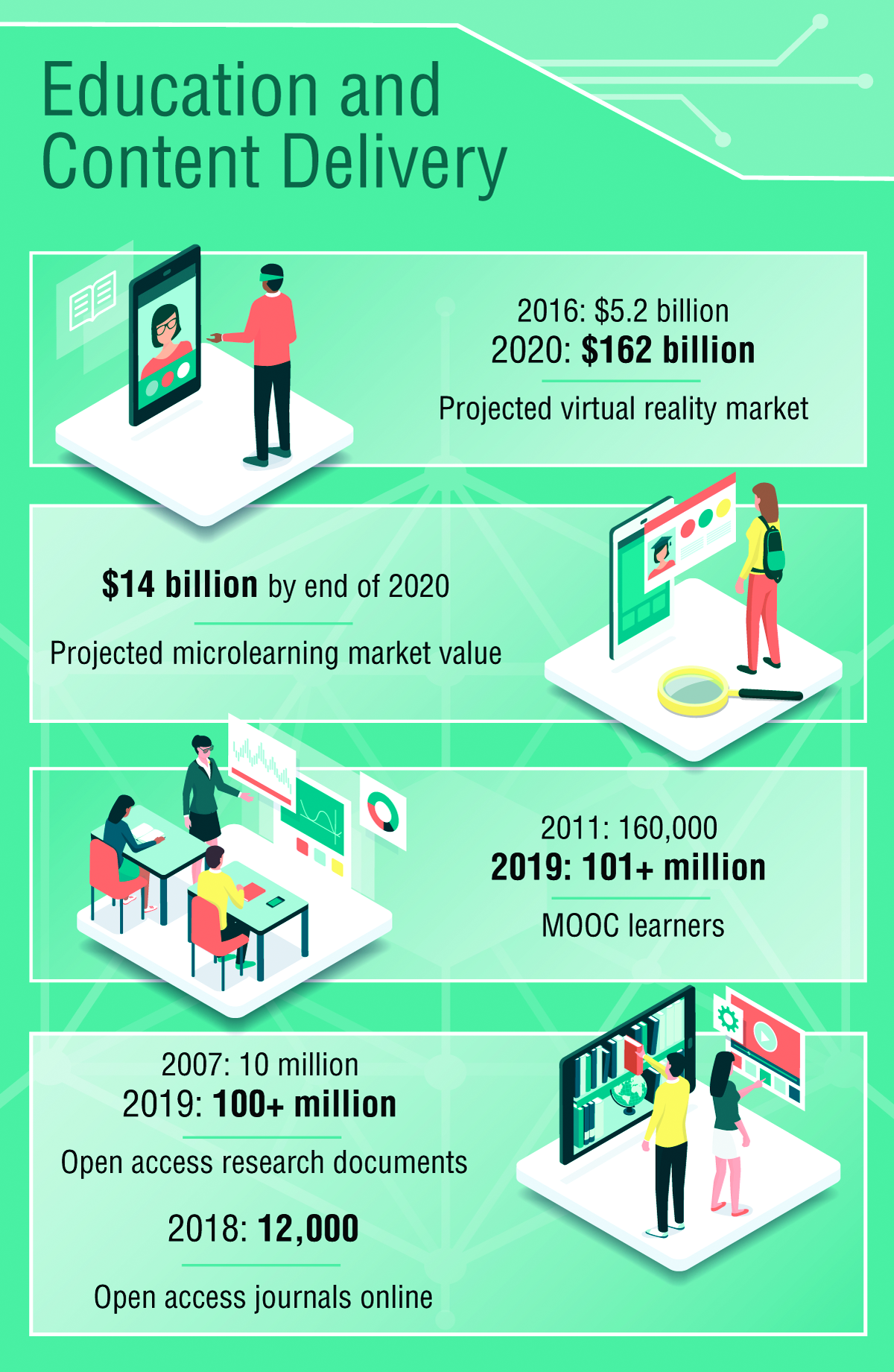

Online learning is now a vast industry and has been harnessed by millions to further professional learning opportunities. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are free online courses available for anyone to enroll.3 MOOCs have been established at Harvard, MIT, Microsoft, and other top universities and institutions in subjects like computer science, data science, business, and more. MOOCs are being replicated in conventional universities and are projected to be a model for adult learning in the coming decade.4

Another trend is the growing interest in microlearning, defined as short educational activities that deal with relatively small learning units utilized at the point where the learner will actually need the information.5

Dr. Buckley sees potential in microlearning for continuing medical education. “It is unlikely that microlearning would be eligible for CME currently unless there were a mechanism for aggregating multiple events into a substantive unit of credit. But the ACCME [Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education] has been very adaptive to various forms of learning, so aggregate microlearning for CME credit may be possible in the future.” He added that the benefits of rapid and reliable access of specific information from a trusted source are significant, and the opportunities for microlearning for chest physicians are almost limitless. “Whether searching for the most updated review of a medical topic, or checking to see if your ICU patient’s sedating medication can cause serotonin syndrome, microlearning is already playing a large role in physician education, just less formal that what’s been used historically,” he said.

Institutions for which professional development learning modules are an important revenue stream will increasingly be challenged to compete with open-access courses of varying quality.

A key trend identified in 2018 is accelerating higher-education technology adoption and a growing focus on measured outcomes and learning.5 Individuals are interested in personalized learning plans and adaptive learning systems that can provide real-time assessments and immediate feedback. It is expected that learning modules and curricula will be most successful if they are easily accessed, attractively presented, and incorporate immediate feedback on learning progress. Driving technology adoption in higher education in the next 3-5 years will be the proliferation of open educational resources and the rise of new forms of interdisciplinary studies. As the environment for providing and accessing content shifts from pay-to-access to open-access, organizations will need to identify a new value proposition if they wish to grow or maintain related revenue streams.6

The implications of these changes in demand are profound for creators of continuing education content for medical professionals. Major investment will be needed in new, possibly costly platforms that deliver high-quality content with accessibility and interactive elements to meet the demands of professionals, the younger generation in particular.7 The market will continue to develop new technology to serve continuing education needs and preferences of users, thus fueling competition among stakeholders. With the proliferation of free and low-cost online and virtual programs, continuing education providers may experience a negative impact on an important revenue stream if they don’t identify a competitive advantage that meets the needs of tomorrow’s workforce. However, educational programs and courses that use artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and augmented reality to enhance the learning experience are likely to experience higher levels of use in the coming years.8

Workforce diversity and mentoring

A global economy requires organizations to seek a diverse workforce. Diversity can also lead to higher levels of profitability and employee satisfaction. As such, it will be essential for organizations to increase opportunities for individuals from diverse backgrounds to join the workforce. Creating a diverse workforce will mean removing barriers of time and location to skill building through online learning opportunities and facilitation of interdisciplinary career paths.

A critical piece of the emerging model of career development will be mentoring. Many professionals in today’s workforce view mentoring as an opportunity to gain immediate skills and knowledge quickly and effectively. Mentoring has evolved from pairing young professionals with seasoned veterans to creating relationships that match individuals with others who have the skills and knowledge they desire to learn about – regardless of age and experience. Institutions striving to develop a diverse workforce will need many individuals to serve as both mentors and mentees. When searching for solutions to work-related challenges, individuals will increasingly turn to knowledge management and collaboration systems (virtual mentoring) that provide them with the opportunity to match their needs in an efficient and effective manner.

Dr. Buckley values peer-to-peer mentoring as a means of accessing and sharing niche expertise among colleagues, but he acknowledges the difficulties in incorporating it into everyday practice. “The biggest obstacles are probably time and access. More and more learners and mentors are recognizing the tremendous value of effective mentorship, so convincing people is less of an issue than finding time,” he said.

Mentorship will continue to play a central role in the advancement of one’s career, yet women and minorities find it increasingly difficult to match with a mentor within the workplace. These candidates are likely to seek external opportunities. Individuals will evaluate the experience, opportunities for career advancement and the level of diversity and inclusion when seeking and accepting a new job.

Dr. Buckley sees both progress and remaining challenges in reducing barriers to underrepresented groups in medical institutions. “There continues to be a need for ongoing training to help individuals and institutions recognize and eliminate their barriers and biases, both conscious and subconscious, that interfere with achieving diversity and inclusion. Another important limitation is the pipeline of underrepresented groups that are pursuing careers in medicine. We need to do more empowerment, encouragement, and recruitment of underrepresented groups at a very early stage in their education if we ever expect to achieve our goals.”

Future challenges

The transformations described above will require a large investment by physicians aiming to maintain professional currency, by creators of continuing education content, and by employers seeking a diversified workforce. All these stakeholders have an interest in the future direction of continuing education and professional training. The development of new platforms for delivery of content that is easily accessible, formatted for a wide variety of devices, and built with real-time feedback functions will require a significant commitment of resources.

References

1. IDC Trackers. “Worldwide semiannual augmented and virtual reality spending guide.” Accessed Sept. 3, 2019.

2. ASAE. “Foresight Works: User’s Guide.” ASAE Foundation, 2018.

3. Online Course Report. “The State of MOOC 2016: A year of massive landscape change for massive open online courses.” Accessed Sept. 3, 2019.

4. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “Postsecondary Success: Data and Information.” Accessed Sept. 4, 2019.

5. QYReports. “The Microlearning Market Report, 2018.” Accessed Sept. 4, 2019.

6. Adams S et al. “NMC Horizon Report: 2018 Higher Education Edition.” Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2018.

7. An M. “Content trends: Preferences emerge along generational fault lines.” Hubspot: Nov. 6, 2017; updated Dec 14, 2018.

8. Grajek S and Grama J. “Higher education’s 2018 trend watch and top 10 strategic technologies.” EDUCAUSE Review, Jan 29, 2018.

Note: Background research performed by Avenue M Group.

CHEST Inspiration is a collection of programmatic initiatives developed by the American College of Chest Physicians leadership and aimed at stimulating and encouraging innovation within the association. One of the components of CHEST Inspiration is the Environmental Scan, a series of articles focusing on the internal and external environmental factors that bear on success currently and in the future. See “Envisioning the Future: The CHEST Environmental Scan,” CHEST Physician, June 2019, p. 44, for an introduction to the series.

Keeping up to date and maintaining currency on developments in medicine are a routine part of medical practice, but the means by which this is accomplished are changing rapidly. Training, maintenance of certification, continuing education, mentoring, and career development will all be transformed in the coming years because of new technology and changing needs of physicians. Traditional learning channels such as print media and in-person courses will give way to options that emphasize ease of access, collaboration with fellow learners, and digitally optimized content.

Education and content delivery

The primary distribution channels for keeping medical professionals current in their specialty will continue to shift away from print publications and expand to digital outlets including podcasts, video, and online access to content.1 Individuals seeking to keep up professionally will increasingly turn to resources that can be found quickly and easily, for example, through voice search. Content that has been optimized to appear quickly and with a clear layout adapted to a wide variety of devices will most likely be consumed at a higher rate than resources from well-established organizations that have not transformed their continuing education content. There is already a growing demand for video and audiocasts accessible via mobile device.2

John D. Buckley, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine and vice chair for education at Indiana University, Indianapolis, sees the transformation of content delivery as a net plus for physicians, with a couple of caveats. He noted, “Whether it is conducting an in-depth literature search, reading/streaming a review lecture, or simply confirming a medical fact, quick access can enhance patient care and advance learning in a manner that meets an individual’s learning style. One potential downside is the risk of unreliable information, so accessing trustworthy sources is essential. Another potential downside is that, while accessing the answer to a very specific question can be done very easily, this might compromise additional learning of related material that used to occur when you had to read an entire book chapter to answer your question. Not only did you answer your question, you learned a lot of other relevant information along the way.”

Online learning is now a vast industry and has been harnessed by millions to further professional learning opportunities. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are free online courses available for anyone to enroll.3 MOOCs have been established at Harvard, MIT, Microsoft, and other top universities and institutions in subjects like computer science, data science, business, and more. MOOCs are being replicated in conventional universities and are projected to be a model for adult learning in the coming decade.4

Another trend is the growing interest in microlearning, defined as short educational activities that deal with relatively small learning units utilized at the point where the learner will actually need the information.5

Dr. Buckley sees potential in microlearning for continuing medical education. “It is unlikely that microlearning would be eligible for CME currently unless there were a mechanism for aggregating multiple events into a substantive unit of credit. But the ACCME [Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education] has been very adaptive to various forms of learning, so aggregate microlearning for CME credit may be possible in the future.” He added that the benefits of rapid and reliable access of specific information from a trusted source are significant, and the opportunities for microlearning for chest physicians are almost limitless. “Whether searching for the most updated review of a medical topic, or checking to see if your ICU patient’s sedating medication can cause serotonin syndrome, microlearning is already playing a large role in physician education, just less formal that what’s been used historically,” he said.

Institutions for which professional development learning modules are an important revenue stream will increasingly be challenged to compete with open-access courses of varying quality.

A key trend identified in 2018 is accelerating higher-education technology adoption and a growing focus on measured outcomes and learning.5 Individuals are interested in personalized learning plans and adaptive learning systems that can provide real-time assessments and immediate feedback. It is expected that learning modules and curricula will be most successful if they are easily accessed, attractively presented, and incorporate immediate feedback on learning progress. Driving technology adoption in higher education in the next 3-5 years will be the proliferation of open educational resources and the rise of new forms of interdisciplinary studies. As the environment for providing and accessing content shifts from pay-to-access to open-access, organizations will need to identify a new value proposition if they wish to grow or maintain related revenue streams.6

The implications of these changes in demand are profound for creators of continuing education content for medical professionals. Major investment will be needed in new, possibly costly platforms that deliver high-quality content with accessibility and interactive elements to meet the demands of professionals, the younger generation in particular.7 The market will continue to develop new technology to serve continuing education needs and preferences of users, thus fueling competition among stakeholders. With the proliferation of free and low-cost online and virtual programs, continuing education providers may experience a negative impact on an important revenue stream if they don’t identify a competitive advantage that meets the needs of tomorrow’s workforce. However, educational programs and courses that use artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and augmented reality to enhance the learning experience are likely to experience higher levels of use in the coming years.8

Workforce diversity and mentoring

A global economy requires organizations to seek a diverse workforce. Diversity can also lead to higher levels of profitability and employee satisfaction. As such, it will be essential for organizations to increase opportunities for individuals from diverse backgrounds to join the workforce. Creating a diverse workforce will mean removing barriers of time and location to skill building through online learning opportunities and facilitation of interdisciplinary career paths.

A critical piece of the emerging model of career development will be mentoring. Many professionals in today’s workforce view mentoring as an opportunity to gain immediate skills and knowledge quickly and effectively. Mentoring has evolved from pairing young professionals with seasoned veterans to creating relationships that match individuals with others who have the skills and knowledge they desire to learn about – regardless of age and experience. Institutions striving to develop a diverse workforce will need many individuals to serve as both mentors and mentees. When searching for solutions to work-related challenges, individuals will increasingly turn to knowledge management and collaboration systems (virtual mentoring) that provide them with the opportunity to match their needs in an efficient and effective manner.

Dr. Buckley values peer-to-peer mentoring as a means of accessing and sharing niche expertise among colleagues, but he acknowledges the difficulties in incorporating it into everyday practice. “The biggest obstacles are probably time and access. More and more learners and mentors are recognizing the tremendous value of effective mentorship, so convincing people is less of an issue than finding time,” he said.

Mentorship will continue to play a central role in the advancement of one’s career, yet women and minorities find it increasingly difficult to match with a mentor within the workplace. These candidates are likely to seek external opportunities. Individuals will evaluate the experience, opportunities for career advancement and the level of diversity and inclusion when seeking and accepting a new job.

Dr. Buckley sees both progress and remaining challenges in reducing barriers to underrepresented groups in medical institutions. “There continues to be a need for ongoing training to help individuals and institutions recognize and eliminate their barriers and biases, both conscious and subconscious, that interfere with achieving diversity and inclusion. Another important limitation is the pipeline of underrepresented groups that are pursuing careers in medicine. We need to do more empowerment, encouragement, and recruitment of underrepresented groups at a very early stage in their education if we ever expect to achieve our goals.”

Future challenges

The transformations described above will require a large investment by physicians aiming to maintain professional currency, by creators of continuing education content, and by employers seeking a diversified workforce. All these stakeholders have an interest in the future direction of continuing education and professional training. The development of new platforms for delivery of content that is easily accessible, formatted for a wide variety of devices, and built with real-time feedback functions will require a significant commitment of resources.

References

1. IDC Trackers. “Worldwide semiannual augmented and virtual reality spending guide.” Accessed Sept. 3, 2019.

2. ASAE. “Foresight Works: User’s Guide.” ASAE Foundation, 2018.

3. Online Course Report. “The State of MOOC 2016: A year of massive landscape change for massive open online courses.” Accessed Sept. 3, 2019.

4. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “Postsecondary Success: Data and Information.” Accessed Sept. 4, 2019.

5. QYReports. “The Microlearning Market Report, 2018.” Accessed Sept. 4, 2019.

6. Adams S et al. “NMC Horizon Report: 2018 Higher Education Edition.” Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2018.

7. An M. “Content trends: Preferences emerge along generational fault lines.” Hubspot: Nov. 6, 2017; updated Dec 14, 2018.

8. Grajek S and Grama J. “Higher education’s 2018 trend watch and top 10 strategic technologies.” EDUCAUSE Review, Jan 29, 2018.

Note: Background research performed by Avenue M Group.

CHEST Inspiration is a collection of programmatic initiatives developed by the American College of Chest Physicians leadership and aimed at stimulating and encouraging innovation within the association. One of the components of CHEST Inspiration is the Environmental Scan, a series of articles focusing on the internal and external environmental factors that bear on success currently and in the future. See “Envisioning the Future: The CHEST Environmental Scan,” CHEST Physician, June 2019, p. 44, for an introduction to the series.

Keeping up to date and maintaining currency on developments in medicine are a routine part of medical practice, but the means by which this is accomplished are changing rapidly. Training, maintenance of certification, continuing education, mentoring, and career development will all be transformed in the coming years because of new technology and changing needs of physicians. Traditional learning channels such as print media and in-person courses will give way to options that emphasize ease of access, collaboration with fellow learners, and digitally optimized content.

Education and content delivery

The primary distribution channels for keeping medical professionals current in their specialty will continue to shift away from print publications and expand to digital outlets including podcasts, video, and online access to content.1 Individuals seeking to keep up professionally will increasingly turn to resources that can be found quickly and easily, for example, through voice search. Content that has been optimized to appear quickly and with a clear layout adapted to a wide variety of devices will most likely be consumed at a higher rate than resources from well-established organizations that have not transformed their continuing education content. There is already a growing demand for video and audiocasts accessible via mobile device.2

John D. Buckley, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine and vice chair for education at Indiana University, Indianapolis, sees the transformation of content delivery as a net plus for physicians, with a couple of caveats. He noted, “Whether it is conducting an in-depth literature search, reading/streaming a review lecture, or simply confirming a medical fact, quick access can enhance patient care and advance learning in a manner that meets an individual’s learning style. One potential downside is the risk of unreliable information, so accessing trustworthy sources is essential. Another potential downside is that, while accessing the answer to a very specific question can be done very easily, this might compromise additional learning of related material that used to occur when you had to read an entire book chapter to answer your question. Not only did you answer your question, you learned a lot of other relevant information along the way.”

Online learning is now a vast industry and has been harnessed by millions to further professional learning opportunities. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are free online courses available for anyone to enroll.3 MOOCs have been established at Harvard, MIT, Microsoft, and other top universities and institutions in subjects like computer science, data science, business, and more. MOOCs are being replicated in conventional universities and are projected to be a model for adult learning in the coming decade.4

Another trend is the growing interest in microlearning, defined as short educational activities that deal with relatively small learning units utilized at the point where the learner will actually need the information.5

Dr. Buckley sees potential in microlearning for continuing medical education. “It is unlikely that microlearning would be eligible for CME currently unless there were a mechanism for aggregating multiple events into a substantive unit of credit. But the ACCME [Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education] has been very adaptive to various forms of learning, so aggregate microlearning for CME credit may be possible in the future.” He added that the benefits of rapid and reliable access of specific information from a trusted source are significant, and the opportunities for microlearning for chest physicians are almost limitless. “Whether searching for the most updated review of a medical topic, or checking to see if your ICU patient’s sedating medication can cause serotonin syndrome, microlearning is already playing a large role in physician education, just less formal that what’s been used historically,” he said.

Institutions for which professional development learning modules are an important revenue stream will increasingly be challenged to compete with open-access courses of varying quality.

A key trend identified in 2018 is accelerating higher-education technology adoption and a growing focus on measured outcomes and learning.5 Individuals are interested in personalized learning plans and adaptive learning systems that can provide real-time assessments and immediate feedback. It is expected that learning modules and curricula will be most successful if they are easily accessed, attractively presented, and incorporate immediate feedback on learning progress. Driving technology adoption in higher education in the next 3-5 years will be the proliferation of open educational resources and the rise of new forms of interdisciplinary studies. As the environment for providing and accessing content shifts from pay-to-access to open-access, organizations will need to identify a new value proposition if they wish to grow or maintain related revenue streams.6

The implications of these changes in demand are profound for creators of continuing education content for medical professionals. Major investment will be needed in new, possibly costly platforms that deliver high-quality content with accessibility and interactive elements to meet the demands of professionals, the younger generation in particular.7 The market will continue to develop new technology to serve continuing education needs and preferences of users, thus fueling competition among stakeholders. With the proliferation of free and low-cost online and virtual programs, continuing education providers may experience a negative impact on an important revenue stream if they don’t identify a competitive advantage that meets the needs of tomorrow’s workforce. However, educational programs and courses that use artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and augmented reality to enhance the learning experience are likely to experience higher levels of use in the coming years.8

Workforce diversity and mentoring

A global economy requires organizations to seek a diverse workforce. Diversity can also lead to higher levels of profitability and employee satisfaction. As such, it will be essential for organizations to increase opportunities for individuals from diverse backgrounds to join the workforce. Creating a diverse workforce will mean removing barriers of time and location to skill building through online learning opportunities and facilitation of interdisciplinary career paths.

A critical piece of the emerging model of career development will be mentoring. Many professionals in today’s workforce view mentoring as an opportunity to gain immediate skills and knowledge quickly and effectively. Mentoring has evolved from pairing young professionals with seasoned veterans to creating relationships that match individuals with others who have the skills and knowledge they desire to learn about – regardless of age and experience. Institutions striving to develop a diverse workforce will need many individuals to serve as both mentors and mentees. When searching for solutions to work-related challenges, individuals will increasingly turn to knowledge management and collaboration systems (virtual mentoring) that provide them with the opportunity to match their needs in an efficient and effective manner.

Dr. Buckley values peer-to-peer mentoring as a means of accessing and sharing niche expertise among colleagues, but he acknowledges the difficulties in incorporating it into everyday practice. “The biggest obstacles are probably time and access. More and more learners and mentors are recognizing the tremendous value of effective mentorship, so convincing people is less of an issue than finding time,” he said.

Mentorship will continue to play a central role in the advancement of one’s career, yet women and minorities find it increasingly difficult to match with a mentor within the workplace. These candidates are likely to seek external opportunities. Individuals will evaluate the experience, opportunities for career advancement and the level of diversity and inclusion when seeking and accepting a new job.

Dr. Buckley sees both progress and remaining challenges in reducing barriers to underrepresented groups in medical institutions. “There continues to be a need for ongoing training to help individuals and institutions recognize and eliminate their barriers and biases, both conscious and subconscious, that interfere with achieving diversity and inclusion. Another important limitation is the pipeline of underrepresented groups that are pursuing careers in medicine. We need to do more empowerment, encouragement, and recruitment of underrepresented groups at a very early stage in their education if we ever expect to achieve our goals.”

Future challenges

The transformations described above will require a large investment by physicians aiming to maintain professional currency, by creators of continuing education content, and by employers seeking a diversified workforce. All these stakeholders have an interest in the future direction of continuing education and professional training. The development of new platforms for delivery of content that is easily accessible, formatted for a wide variety of devices, and built with real-time feedback functions will require a significant commitment of resources.

References

1. IDC Trackers. “Worldwide semiannual augmented and virtual reality spending guide.” Accessed Sept. 3, 2019.

2. ASAE. “Foresight Works: User’s Guide.” ASAE Foundation, 2018.

3. Online Course Report. “The State of MOOC 2016: A year of massive landscape change for massive open online courses.” Accessed Sept. 3, 2019.

4. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “Postsecondary Success: Data and Information.” Accessed Sept. 4, 2019.

5. QYReports. “The Microlearning Market Report, 2018.” Accessed Sept. 4, 2019.

6. Adams S et al. “NMC Horizon Report: 2018 Higher Education Edition.” Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2018.

7. An M. “Content trends: Preferences emerge along generational fault lines.” Hubspot: Nov. 6, 2017; updated Dec 14, 2018.

8. Grajek S and Grama J. “Higher education’s 2018 trend watch and top 10 strategic technologies.” EDUCAUSE Review, Jan 29, 2018.

Note: Background research performed by Avenue M Group.

CHEST Inspiration is a collection of programmatic initiatives developed by the American College of Chest Physicians leadership and aimed at stimulating and encouraging innovation within the association. One of the components of CHEST Inspiration is the Environmental Scan, a series of articles focusing on the internal and external environmental factors that bear on success currently and in the future. See “Envisioning the Future: The CHEST Environmental Scan,” CHEST Physician, June 2019, p. 44, for an introduction to the series.