User login

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) defines early pregnancy loss (EPL) as a nonviable, intrauterine pregnancy up to 12 6/7 weeks’ gestation.1 The term EPL has been used interchangeably with miscarriage, spontaneous abortion, and early pregnancy failure; the preferred terms among US women who experience pregnancy loss are EPL and miscarriage.2 EPL is the most common complication of early pregnancy and accounts for up to 15% to 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies.3

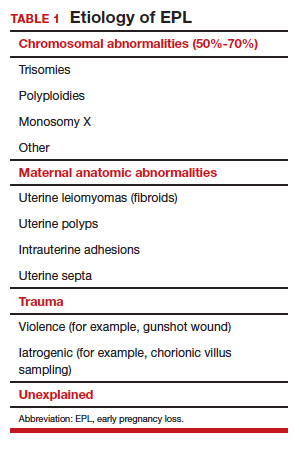

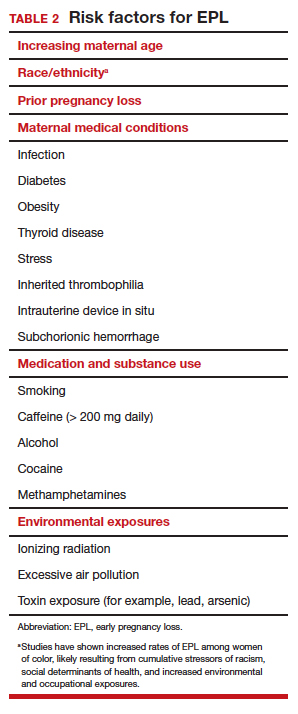

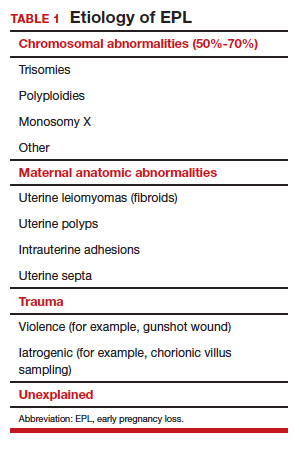

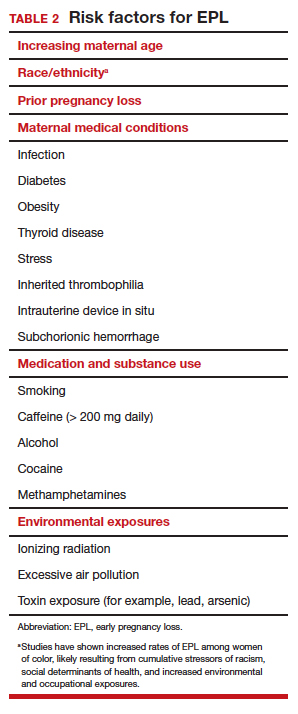

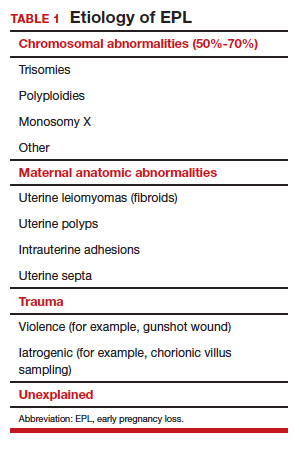

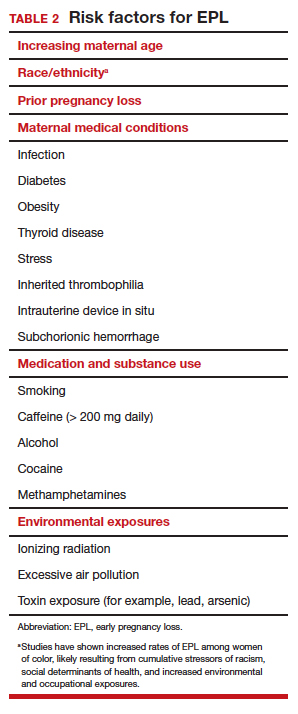

The most common cause of EPL is a chromosomal abnormality (TABLE 1). Other common etiologies include structural abnormalities, such as uterine fibroids or polyps. Risk factors for EPL include maternal age, prior pregnancy loss, and various maternal conditions and medication and substance use (TABLE 2).

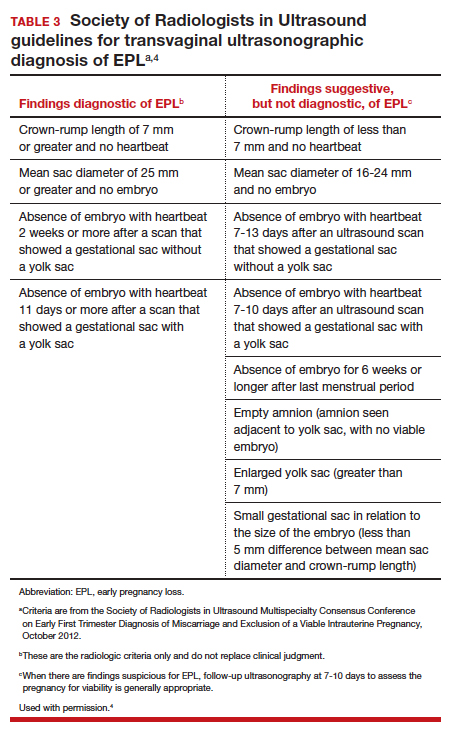

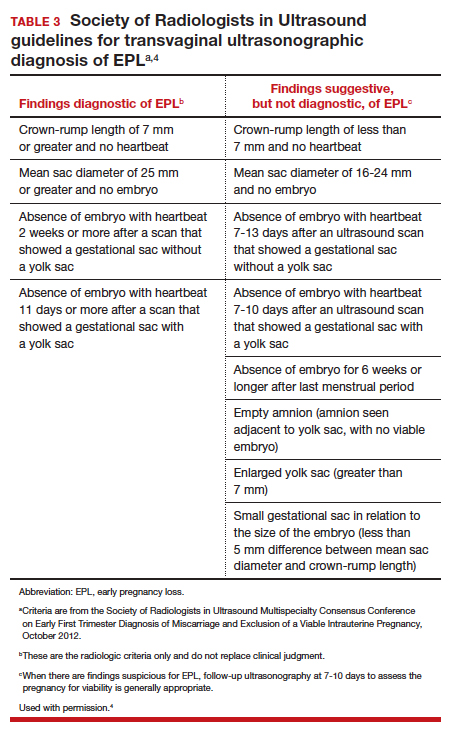

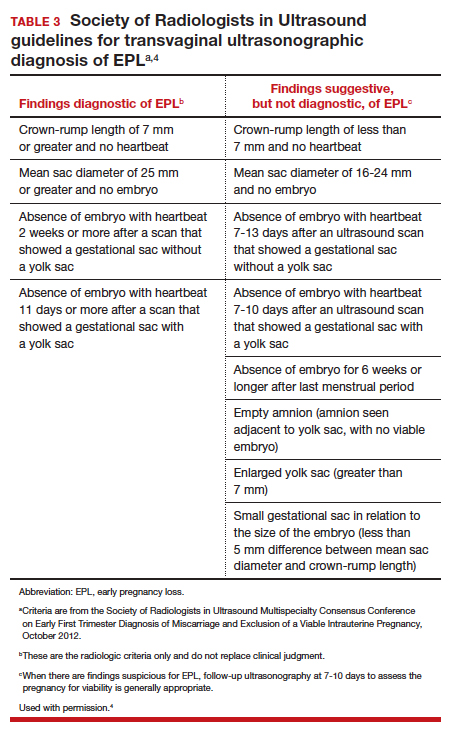

Definitive diagnosis of EPL often requires more than 1 ultrasonography scan or other examination to determine whether a pregnancy is nonviable versus too early to confirm viability. The consensus guidelines from the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound provide transvaginal ultrasonographic criteria to diagnose EPL (TABLE 3).4 Two of the diagnostic criteria require only 1 ultrasonography scan while the others require repeat ultrasonography.

Note that a definitive diagnosis may be more important to some patients than others due to differing pregnancy intent and/or desirableness. Patients may choose to take action in terms of medication or uterine aspiration based on suspicion of EPL, or they may wish to end the pregnancy regardless of EPL diagnosis.

Management options for EPL

EPL can be managed expectantly, with medication, or with uterine aspiration. These methods have different risks and benefits, and in most cases all should be made available to women who experience EPL.5-7

Expectant management

Expectant management involves waiting for the body to spontaneously expel the nonviable pregnancy. In the absence of any signs of infection, hemodynamic instability, or other medical instability, it is safe and reasonable to wait a month or more before intervening, according to patient choice. Expectant management is up to 80% effective.8

Medication management

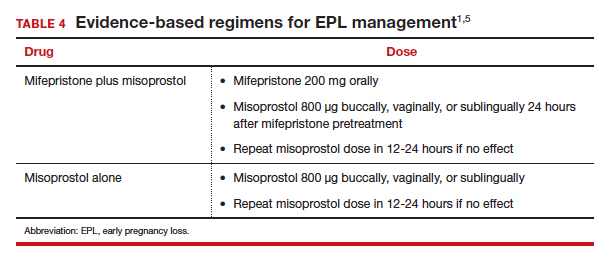

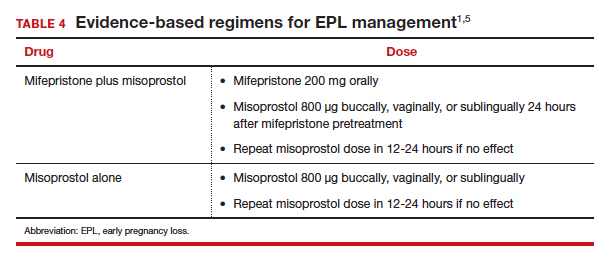

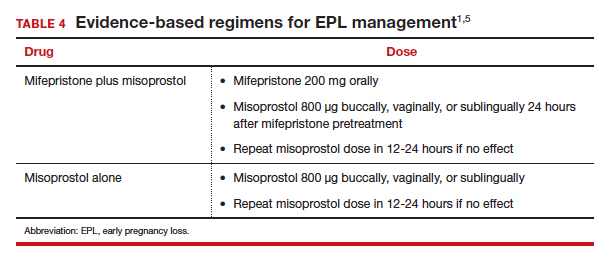

Medication management entails using mifepristone and misoprostol, or misoprostol alone, to cause uterine contractions to expel the pregnancy. A landmark study demonstrated that medication management of EPL with the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol is significantly more effective than misoprostol alone.9 While the mean cost of mifepristone is approximately $90 per dose, its addition is cost-effective given the increased efficacy.10

The evidence-based combination regimen is to provide mifepristone 200 mg orally, followed 24 hours later by misoprostol 800 µg vaginally, for a success rate of 87.8% by 8 days, and 91.2% by 30 days posttreatment. Success rates can be increased further by adding a second dose of misoprostol to take as needed.5

We strongly recommend using the combination regimen if you have access to mifepristone. If you do not have access to mifepristone in your clinical setting, perhaps this indication for use can help facilitate getting it onto your formulary. (See “Ordering mifepristone” below.)

Without access to mifepristone, medication abortion still should be offered after discussing the decreased efficacy with patients. The first-trimester misoprostol-only regimen for EPL is to give misoprostol 800 µg buccally, vaginally, or sublingually, with a second dose if there is no effect (TABLE 4).1,5 For losses after 9 weeks, some data suggest adding additional doses of misoprostol 400 µg every 3 hours until expulsion.11

- There are 2 distributors of mifepristone in the United States. Danco (www.earlyoptionpill.com) distributes the branded Mifeprex and GenBioPro (www.genbiopro.com) distributes generic mifepristone.

- To order mifepristone, 1 health care provider from your clinic or facility must read and sign the distributor’s prescriber agreement and account setup form. These forms and instructions can be found on each distributor’s website. Future orders can be made by calling the distributor directly (Danco: 1-877-432-7596; GenBioPro: 1-855-643-3463).

- The shelf life of mifepristone is 18 months.

- Each patient who receives mifepristone needs to read and sign a patient agreement (available on distributor websites), as required by the US Food and Drug Administration–approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.

Continue to: Uterine aspiration...

Uterine aspiration

Uterine aspiration is the third management option for EPL and is virtually 100% successful. Although aspiration is used when expectant or medication management fails, it is also a first-line option based on patient choice or contraindications to the other 2 management options.

We recommend either manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) or electric vacuum aspiration (EVA); sharp curettage almost never should be used. Uterine aspiration can be performed safely in a clinic, emergency department, or operating room (OR) setting, depending on patient characteristics and desires.12-14 For various reasons, many patients prefer outpatient management. These reasons may include avoiding the costs and delays associated with OR management, wanting more control over who performs the procedure, or avoiding more significant/general anesthesia. MVA in the outpatient setting is the most cost-effective approach to uterine aspiration.15

Choosing a management approach

There are virtually no contraindications for uterine aspiration. Expectant and medication management are contraindicated (and uterine aspiration is recommended) in the setting of bleeding disorders, anticoagulation, suspected intrauterine infection, suspected molar pregnancy, significant cardiopulmonary disease, or any condition for which heavy, unsupervised bleeding might be dangerous.1 Uterine aspiration offers immediate resolution, with a procedure usually lasting 3 to 10 minutes. By contrast, expectant and medication management offer a less predictable time to resolution and, often, a more prolonged period of active pregnancy expulsion.

In the absence of a contraindication, patient choice should determine which management option is used. All 3 options are similarly safe and effective, and the differences that do exist are acceptable to patients as long as they are allowed to access their preferred EPL management method.5,6,16 Patient satisfaction is associated directly with the ability to choose the method of preference.

Managing pain

Pain management should be offered to all women diagnosed with EPL. Those who choose expectant or medication management likely will require only oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). A minority may require the addition of a small number of narcotic pain pills.17

Women who choose uterine aspiration also should be offered pain management. All patients should be given a paracervical block; other medications can include NSAIDs, an oral benzodiazepine, intravenous (IV) sedation, or even general anesthesia/monitored airway care.17

Patients’ expectations about pain management should be addressed directly during initial counseling. This may help patients decide what type of management and treatment location they might prefer.

Checking blood type: Is it necessary?

The ACOG practice bulletin for EPL states, “administration of Rh D immune globulin should be considered in cases of early pregnancy loss, especially those that are later in the first trimester.”1 A growing body of evidence indicates that Rho(D) immune globulin likely is unnecessary in early pregnancy.

A recent prospective cohort study of 42 women who were at 5 to 12 weeks’ gestation found that the fetal red blood cell concentration was below the calculated threshold for Rh sensitization.18 In light of recent evidence, the National Abortion Federation now recommends foregoing Rh testing and provision of Rh immune globulin at less than 8 weeks’ gestation for uterine aspiration and at less than 10 weeks’ gestation for medication abortion.19

We feel there is sufficient evidence to forego Rh testing in EPL at similar gestational ages, although this is not yet reflected in US societal guidelines. (It is already standard practice in some countries.) Although the risk of Rh alloimmunization is low, the risk of significant consequences in the event of Rh alloimmunization is high. Currently, it also is reasonable to continue giving Rho(D) immune globulin to Rh-negative patients who experience EPL at any gestational age. A lower dose (50 µg) is sufficient for EPL; the standard 300-µg dose also is acceptable.20

We anticipate that society and ACOG guidelines will change in the next few years as the body of evidence increases, and practice should change to reflect new guidance.

Continue to: Prophylactic antibiotics...

Prophylactic antibiotics

The risk of infection with EPL is low overall regardless of the management approach.1 Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended for patients undergoing uterine aspiration but are not necessary in the setting of expectant or medication management. We recommend prophylaxis with 1 dose of oral doxycycline 200 mg or oral azithromycin 500 mg approximately 30 minutes to 1 hour prior to uterine aspiration.21 Alternatives include 1 dose of oral metronidazole 500 mg or, if the patient is unable to take oral medications, IV cefazolin 2 g.

A multisite international randomized controlled trial concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis before uterine aspiration for EPL did not significantly reduce the risk of infection.22 However, there was a significant reduction in pelvic infection with antibiotic administration for the subgroup of women who underwent MVA, which is our recommended approach (along with EVA, and opposed to sharp curettage) for outpatient EPL management.

Follow-up after EPL

In-person follow-up after treatment of EPL is not medically necessary. A repeat ultrasonography 1 to 2 weeks after expectant or medication management can be helpful to confirm completion of the process, and clinicians should focus on presence or absence of a gestational sac to determine if further management is needed.1

Follow-up by telemedicine or phone also is an option and may be preferred in the following situations:

- the patient lives far from the clinic

- travel to the clinic is difficult or expensive

- the patient has child-care issues

- there is a global pandemic necessitating physical distancing.

If the patient’s reported history and symptoms are consistent with a completed process, no further intervention is indicated.

If ongoing EPL is a concern, ask the patient to come in for an evaluation and ultrasonography. If visiting the clinic is still a challenge, following with urine or serum human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) levels also is acceptable. Experts recommend waiting 4 weeks before expecting a negative urine HCG measurement, although up to 25% of women with a completed EPL will still have a positive test at 4 weeks.23,24

A postprocedure serum HCG is more helpful if a preprocedure HCG level already is known. Numerous studies have evaluated phone follow-up after medication abortion and it is reasonable to translate these practices to follow-up after EPL, recognizing that direct data looking at alternative EPL follow-up are much more limited.23,25-30

The benefit of HCG follow-up at a scheduled time (such as 1 week) is less clear for EPL than for medication abortion, as HCG trends are less predictable in the setting of EPL. However, if the pregnancy has passed, a significant drop in the HCG level would be expected. It is important to take into account the patient’s history and clinical symptoms and consider in-person evaluation with possible ultrasonography if there is concern that the pregnancy tissue has not passed.

Pay attention to mental health

It is critical to assess the patient’s mental and emotional health. This should be done both at the time of EPL diagnosis and management and again at follow-up. Both patients and their partners can struggle after experiencing EPL, and they may suffer from prolonged posttraumatic stress.31

Often, EPL occurs before people have shared the news about their pregnancy. This can amplify the sense of isolation and sadness many women report. Equally critical is recognizing that not all women who experience EPL grieve, and clinicians should normalize patient experiences and feelings. Provider language is important. We recommend use of these questions and phrases:

- I’m so sorry for your loss.

- How are you feeling?

- How have you been doing since I saw you last?

- Your friends/family/partner may be grieving differently or at a different pace than you—this is normal.

- Just because the EPL process is complete doesn’t necessarily mean your processing and/or grieving is over.

- Whatever you’re feeling is okay.

Continue to: Address desire for future pregnancy or contraception...

Address desire for future pregnancy or contraception

No additional workup is necessary after EPL unless a patient is experiencing recurrent pregnancy loss. We do recommend discussing plans for future conception. If a patient wants to conceive again as soon as possible, she can start trying when she feels emotionally ready (even before her next menstrual period). One study found that the ability to conceive and those pregnancy outcomes were the same when patients were randomly assigned to start trying immediately versus waiting 3 months after EPL.32

Alternatively, a patient may want to prevent pregnancy after EPL, and this information should be explicitly elicited and addressed with comprehensive contraception counseling as needed. All forms of contraception can be initiated immediately on successful management of EPL. All contraceptive methods, including an intrauterine device, can be initiated immediately following uterine aspiration.1,33,34

Patients should be reminded that if they delay contraception initiation by more than 7 days, they are potentially at risk for pregnancy.35 Most importantly, clinicians should not make assumptions about future pregnancy desires and should ask open-ended questions to provide appropriate patient counseling.

Finally, patients may feel additional anxiety in a subsequent pregnancy. It is helpful to acknowledge this and perhaps even offer earlier and more frequent visits in early pregnancy to help reduce anxiety. EPL is commonly experienced, and unfortunately it is sometimes poorly addressed by clinicians.

We hope this guidance will help you provide excellent, evidence-based, and sensitive care that will not only manage your patient’s EPL but also make the experience as positive as possible. ●

- Early pregnancy loss (EPL) is common, occurring in up to 15% to 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies.

- EPL can be managed expectantly, with medication, or by uterine aspiration.

- There are virtually no contraindications to uterine aspiration.

- Contraindications to expectant or medication management include any situation in which heavy, unsupervised bleeding might be dangerous.

- In the absence of contraindications, patient preference should dictate the management approach.

- Mifepristone-misoprostol is more effective than misoprostol alone.

- Manual uterine aspiration in the outpatient setting is the most cost-effective approach to uterine evacuation.

- Rh testing is not necessary at less than 8 weeks’ gestation if choosing uterine aspiration, or at less than 10 weeks’ gestation if choosing expectant or medication management.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated for uterine aspiration, but not for expectant or medication management.

- Ultrasonography follow-up should focus on presence or absence of gestational sac.

- There are viable telemedicine and phone follow-up options that do not require repeat ultrasonography or in-person evaluation.

- There is no need to delay future conception once EPL management is confirmed to be complete.

- It is okay to initiate any contraceptive method immediately on completed management of EPL.

- Feelings toward EPL can be complex and varied; it is helpful to normalize your patients’ experiences, ask open-ended questions, and provide support as needed.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 200: early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e197-e207.

- Clement EG, Horvath S, McAllister A, et al. The language of first-trimester nonviable pregnancy: patient-reported preferences and clarity. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:149-154.

- Ventura SJ, Curtin SC, Abma JC, et al. Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the United States, 1990-2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;60:1-21.

- Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, et al; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Multispecialty Panel on Early First Trimester Diagnosis of Miscarriage and Exclusion of a Viable Uterine Pregnancy. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1443-1451.

- Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, et al. A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:761-769.

- Nanda K, Peloggia A, Grimes D, et al. Expectant care versus surgical treatment for miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(2):CD003518.

- Neilson JP, Hickey M, Vazquez J. Medical treatment for early fetal death (less than 24 weeks). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(3):CD002253.

- Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324:873-875.

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170.

- Nagendra D, Koelper N, Loza-Avalos SE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of nonviable early pregnancy: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e201594.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Wiebe E, Janssen P. Management of spontaneous abortion in family practices and hospitals. Fam Med. 1998;30:293-296.

- Harris LH, Dalton VK, Johnson TR. Surgical management of early pregnancy failure: history, politics, and safe, cost-effective care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:445.e1-e5.

- Dalton VK, Harris L, Weisman CS, et al. Patient preferences, satisfaction, and resource use in office evacuation of early pregnancy failure. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:103-110.

- Rausch M, Lorch S, Chung K, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of surgical versus medical management of early pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:355-360.

- Trinder J, Brocklehurst P, Porter R, et al. Management of miscarriage: expectant, medical, or surgical? Results of randomised controlled trial (Miscarriage Treatment [MIST] trial). BMJ. 2006;332:1235-1240.

- Calvache JA, Delgado-Noguera MF, Lesaffre E, et al. Anaesthesia for evacuation of incomplete miscarriage. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2012(4):CD008681.

- Horvath S, Tsao P, Huang ZY, et al. The concentration of fetal red blood cells in first-trimester pregnant women undergoing uterine aspiration is below the calculated threshold for Rh sensitization. Contraception. 2020;102:1-6.

- National Abortion Federation. 2020 clinical policy guidelines for abortion care. https://www.prochoice.org/education-and-advocacy/cpg. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e59-e70.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 104: antibiotic prophylaxis for gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1180-1189.

- Lissauer D, Wilson A, Hewitt CA, et al. A randomized trial of prophylactic antibiotics for miscarriage surgery. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1012-1021.

- Perriera L, Reeves MF, Chen BA, et al. Feasibility of telephone follow-up after medical abortion. Contraception. 2010:81:143-149.

- Barnhart K, Sammel MD, Chung K, et al. Decline of serum human chorionic gonadotropin and spontaneous complete abortion: defining the normal curve. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 pt 1):975-981.

- Chen MJ, Rounds KM, Creinin MD, et al. Comparing office and telephone follow-up after medical abortion. Contraception. 2016;94:122-126.

- Clark W, Bracken H, Tanenhaus J, et al. Alternatives to a routine follow-up visit for early medical abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):264-272.

- Jackson AV, Dayananda I, Fortin JM, et al. Can women accurately assess the outcome of medical abortion based on symptoms alone? Contraception. 2012;85:192-197.

- Raymond EG, Tan YL, Grant M, et al. Self-assessment of medical abortion outcome using symptoms and home pregnancy testing. Contraception. 2018;97:324-328.

- Raymond EG, Shochet T, Bracken H. Low-sensitivity urine pregnancy testing to assess medical abortion outcome: a systematic review. Contraception. 2018;98:30-35.

- Raymond EG, Grossman D, Mark A, et al. Commentary: no-test medication abortion: a sample protocol for increasing access during a pandemic and beyond. Contraception. 2020;101:361-366.

- Farren J, Jalmbrant M, Ameye L, et al. Post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011864.

- Schliep KC, Mitchell EM, Mumford SL, et al. Trying to conceive after an early pregnancy loss: an assessment on how long couples should wait. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:204-212. DOI: 0.1097/AOG.0000000000001159.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion No. 642: increasing access to contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e44-e48.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US medical eligibility criteria (US MEC) for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) defines early pregnancy loss (EPL) as a nonviable, intrauterine pregnancy up to 12 6/7 weeks’ gestation.1 The term EPL has been used interchangeably with miscarriage, spontaneous abortion, and early pregnancy failure; the preferred terms among US women who experience pregnancy loss are EPL and miscarriage.2 EPL is the most common complication of early pregnancy and accounts for up to 15% to 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies.3

The most common cause of EPL is a chromosomal abnormality (TABLE 1). Other common etiologies include structural abnormalities, such as uterine fibroids or polyps. Risk factors for EPL include maternal age, prior pregnancy loss, and various maternal conditions and medication and substance use (TABLE 2).

Definitive diagnosis of EPL often requires more than 1 ultrasonography scan or other examination to determine whether a pregnancy is nonviable versus too early to confirm viability. The consensus guidelines from the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound provide transvaginal ultrasonographic criteria to diagnose EPL (TABLE 3).4 Two of the diagnostic criteria require only 1 ultrasonography scan while the others require repeat ultrasonography.

Note that a definitive diagnosis may be more important to some patients than others due to differing pregnancy intent and/or desirableness. Patients may choose to take action in terms of medication or uterine aspiration based on suspicion of EPL, or they may wish to end the pregnancy regardless of EPL diagnosis.

Management options for EPL

EPL can be managed expectantly, with medication, or with uterine aspiration. These methods have different risks and benefits, and in most cases all should be made available to women who experience EPL.5-7

Expectant management

Expectant management involves waiting for the body to spontaneously expel the nonviable pregnancy. In the absence of any signs of infection, hemodynamic instability, or other medical instability, it is safe and reasonable to wait a month or more before intervening, according to patient choice. Expectant management is up to 80% effective.8

Medication management

Medication management entails using mifepristone and misoprostol, or misoprostol alone, to cause uterine contractions to expel the pregnancy. A landmark study demonstrated that medication management of EPL with the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol is significantly more effective than misoprostol alone.9 While the mean cost of mifepristone is approximately $90 per dose, its addition is cost-effective given the increased efficacy.10

The evidence-based combination regimen is to provide mifepristone 200 mg orally, followed 24 hours later by misoprostol 800 µg vaginally, for a success rate of 87.8% by 8 days, and 91.2% by 30 days posttreatment. Success rates can be increased further by adding a second dose of misoprostol to take as needed.5

We strongly recommend using the combination regimen if you have access to mifepristone. If you do not have access to mifepristone in your clinical setting, perhaps this indication for use can help facilitate getting it onto your formulary. (See “Ordering mifepristone” below.)

Without access to mifepristone, medication abortion still should be offered after discussing the decreased efficacy with patients. The first-trimester misoprostol-only regimen for EPL is to give misoprostol 800 µg buccally, vaginally, or sublingually, with a second dose if there is no effect (TABLE 4).1,5 For losses after 9 weeks, some data suggest adding additional doses of misoprostol 400 µg every 3 hours until expulsion.11

- There are 2 distributors of mifepristone in the United States. Danco (www.earlyoptionpill.com) distributes the branded Mifeprex and GenBioPro (www.genbiopro.com) distributes generic mifepristone.

- To order mifepristone, 1 health care provider from your clinic or facility must read and sign the distributor’s prescriber agreement and account setup form. These forms and instructions can be found on each distributor’s website. Future orders can be made by calling the distributor directly (Danco: 1-877-432-7596; GenBioPro: 1-855-643-3463).

- The shelf life of mifepristone is 18 months.

- Each patient who receives mifepristone needs to read and sign a patient agreement (available on distributor websites), as required by the US Food and Drug Administration–approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.

Continue to: Uterine aspiration...

Uterine aspiration

Uterine aspiration is the third management option for EPL and is virtually 100% successful. Although aspiration is used when expectant or medication management fails, it is also a first-line option based on patient choice or contraindications to the other 2 management options.

We recommend either manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) or electric vacuum aspiration (EVA); sharp curettage almost never should be used. Uterine aspiration can be performed safely in a clinic, emergency department, or operating room (OR) setting, depending on patient characteristics and desires.12-14 For various reasons, many patients prefer outpatient management. These reasons may include avoiding the costs and delays associated with OR management, wanting more control over who performs the procedure, or avoiding more significant/general anesthesia. MVA in the outpatient setting is the most cost-effective approach to uterine aspiration.15

Choosing a management approach

There are virtually no contraindications for uterine aspiration. Expectant and medication management are contraindicated (and uterine aspiration is recommended) in the setting of bleeding disorders, anticoagulation, suspected intrauterine infection, suspected molar pregnancy, significant cardiopulmonary disease, or any condition for which heavy, unsupervised bleeding might be dangerous.1 Uterine aspiration offers immediate resolution, with a procedure usually lasting 3 to 10 minutes. By contrast, expectant and medication management offer a less predictable time to resolution and, often, a more prolonged period of active pregnancy expulsion.

In the absence of a contraindication, patient choice should determine which management option is used. All 3 options are similarly safe and effective, and the differences that do exist are acceptable to patients as long as they are allowed to access their preferred EPL management method.5,6,16 Patient satisfaction is associated directly with the ability to choose the method of preference.

Managing pain

Pain management should be offered to all women diagnosed with EPL. Those who choose expectant or medication management likely will require only oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). A minority may require the addition of a small number of narcotic pain pills.17

Women who choose uterine aspiration also should be offered pain management. All patients should be given a paracervical block; other medications can include NSAIDs, an oral benzodiazepine, intravenous (IV) sedation, or even general anesthesia/monitored airway care.17

Patients’ expectations about pain management should be addressed directly during initial counseling. This may help patients decide what type of management and treatment location they might prefer.

Checking blood type: Is it necessary?

The ACOG practice bulletin for EPL states, “administration of Rh D immune globulin should be considered in cases of early pregnancy loss, especially those that are later in the first trimester.”1 A growing body of evidence indicates that Rho(D) immune globulin likely is unnecessary in early pregnancy.

A recent prospective cohort study of 42 women who were at 5 to 12 weeks’ gestation found that the fetal red blood cell concentration was below the calculated threshold for Rh sensitization.18 In light of recent evidence, the National Abortion Federation now recommends foregoing Rh testing and provision of Rh immune globulin at less than 8 weeks’ gestation for uterine aspiration and at less than 10 weeks’ gestation for medication abortion.19

We feel there is sufficient evidence to forego Rh testing in EPL at similar gestational ages, although this is not yet reflected in US societal guidelines. (It is already standard practice in some countries.) Although the risk of Rh alloimmunization is low, the risk of significant consequences in the event of Rh alloimmunization is high. Currently, it also is reasonable to continue giving Rho(D) immune globulin to Rh-negative patients who experience EPL at any gestational age. A lower dose (50 µg) is sufficient for EPL; the standard 300-µg dose also is acceptable.20

We anticipate that society and ACOG guidelines will change in the next few years as the body of evidence increases, and practice should change to reflect new guidance.

Continue to: Prophylactic antibiotics...

Prophylactic antibiotics

The risk of infection with EPL is low overall regardless of the management approach.1 Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended for patients undergoing uterine aspiration but are not necessary in the setting of expectant or medication management. We recommend prophylaxis with 1 dose of oral doxycycline 200 mg or oral azithromycin 500 mg approximately 30 minutes to 1 hour prior to uterine aspiration.21 Alternatives include 1 dose of oral metronidazole 500 mg or, if the patient is unable to take oral medications, IV cefazolin 2 g.

A multisite international randomized controlled trial concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis before uterine aspiration for EPL did not significantly reduce the risk of infection.22 However, there was a significant reduction in pelvic infection with antibiotic administration for the subgroup of women who underwent MVA, which is our recommended approach (along with EVA, and opposed to sharp curettage) for outpatient EPL management.

Follow-up after EPL

In-person follow-up after treatment of EPL is not medically necessary. A repeat ultrasonography 1 to 2 weeks after expectant or medication management can be helpful to confirm completion of the process, and clinicians should focus on presence or absence of a gestational sac to determine if further management is needed.1

Follow-up by telemedicine or phone also is an option and may be preferred in the following situations:

- the patient lives far from the clinic

- travel to the clinic is difficult or expensive

- the patient has child-care issues

- there is a global pandemic necessitating physical distancing.

If the patient’s reported history and symptoms are consistent with a completed process, no further intervention is indicated.

If ongoing EPL is a concern, ask the patient to come in for an evaluation and ultrasonography. If visiting the clinic is still a challenge, following with urine or serum human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) levels also is acceptable. Experts recommend waiting 4 weeks before expecting a negative urine HCG measurement, although up to 25% of women with a completed EPL will still have a positive test at 4 weeks.23,24

A postprocedure serum HCG is more helpful if a preprocedure HCG level already is known. Numerous studies have evaluated phone follow-up after medication abortion and it is reasonable to translate these practices to follow-up after EPL, recognizing that direct data looking at alternative EPL follow-up are much more limited.23,25-30

The benefit of HCG follow-up at a scheduled time (such as 1 week) is less clear for EPL than for medication abortion, as HCG trends are less predictable in the setting of EPL. However, if the pregnancy has passed, a significant drop in the HCG level would be expected. It is important to take into account the patient’s history and clinical symptoms and consider in-person evaluation with possible ultrasonography if there is concern that the pregnancy tissue has not passed.

Pay attention to mental health

It is critical to assess the patient’s mental and emotional health. This should be done both at the time of EPL diagnosis and management and again at follow-up. Both patients and their partners can struggle after experiencing EPL, and they may suffer from prolonged posttraumatic stress.31

Often, EPL occurs before people have shared the news about their pregnancy. This can amplify the sense of isolation and sadness many women report. Equally critical is recognizing that not all women who experience EPL grieve, and clinicians should normalize patient experiences and feelings. Provider language is important. We recommend use of these questions and phrases:

- I’m so sorry for your loss.

- How are you feeling?

- How have you been doing since I saw you last?

- Your friends/family/partner may be grieving differently or at a different pace than you—this is normal.

- Just because the EPL process is complete doesn’t necessarily mean your processing and/or grieving is over.

- Whatever you’re feeling is okay.

Continue to: Address desire for future pregnancy or contraception...

Address desire for future pregnancy or contraception

No additional workup is necessary after EPL unless a patient is experiencing recurrent pregnancy loss. We do recommend discussing plans for future conception. If a patient wants to conceive again as soon as possible, she can start trying when she feels emotionally ready (even before her next menstrual period). One study found that the ability to conceive and those pregnancy outcomes were the same when patients were randomly assigned to start trying immediately versus waiting 3 months after EPL.32

Alternatively, a patient may want to prevent pregnancy after EPL, and this information should be explicitly elicited and addressed with comprehensive contraception counseling as needed. All forms of contraception can be initiated immediately on successful management of EPL. All contraceptive methods, including an intrauterine device, can be initiated immediately following uterine aspiration.1,33,34

Patients should be reminded that if they delay contraception initiation by more than 7 days, they are potentially at risk for pregnancy.35 Most importantly, clinicians should not make assumptions about future pregnancy desires and should ask open-ended questions to provide appropriate patient counseling.

Finally, patients may feel additional anxiety in a subsequent pregnancy. It is helpful to acknowledge this and perhaps even offer earlier and more frequent visits in early pregnancy to help reduce anxiety. EPL is commonly experienced, and unfortunately it is sometimes poorly addressed by clinicians.

We hope this guidance will help you provide excellent, evidence-based, and sensitive care that will not only manage your patient’s EPL but also make the experience as positive as possible. ●

- Early pregnancy loss (EPL) is common, occurring in up to 15% to 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies.

- EPL can be managed expectantly, with medication, or by uterine aspiration.

- There are virtually no contraindications to uterine aspiration.

- Contraindications to expectant or medication management include any situation in which heavy, unsupervised bleeding might be dangerous.

- In the absence of contraindications, patient preference should dictate the management approach.

- Mifepristone-misoprostol is more effective than misoprostol alone.

- Manual uterine aspiration in the outpatient setting is the most cost-effective approach to uterine evacuation.

- Rh testing is not necessary at less than 8 weeks’ gestation if choosing uterine aspiration, or at less than 10 weeks’ gestation if choosing expectant or medication management.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated for uterine aspiration, but not for expectant or medication management.

- Ultrasonography follow-up should focus on presence or absence of gestational sac.

- There are viable telemedicine and phone follow-up options that do not require repeat ultrasonography or in-person evaluation.

- There is no need to delay future conception once EPL management is confirmed to be complete.

- It is okay to initiate any contraceptive method immediately on completed management of EPL.

- Feelings toward EPL can be complex and varied; it is helpful to normalize your patients’ experiences, ask open-ended questions, and provide support as needed.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) defines early pregnancy loss (EPL) as a nonviable, intrauterine pregnancy up to 12 6/7 weeks’ gestation.1 The term EPL has been used interchangeably with miscarriage, spontaneous abortion, and early pregnancy failure; the preferred terms among US women who experience pregnancy loss are EPL and miscarriage.2 EPL is the most common complication of early pregnancy and accounts for up to 15% to 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies.3

The most common cause of EPL is a chromosomal abnormality (TABLE 1). Other common etiologies include structural abnormalities, such as uterine fibroids or polyps. Risk factors for EPL include maternal age, prior pregnancy loss, and various maternal conditions and medication and substance use (TABLE 2).

Definitive diagnosis of EPL often requires more than 1 ultrasonography scan or other examination to determine whether a pregnancy is nonviable versus too early to confirm viability. The consensus guidelines from the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound provide transvaginal ultrasonographic criteria to diagnose EPL (TABLE 3).4 Two of the diagnostic criteria require only 1 ultrasonography scan while the others require repeat ultrasonography.

Note that a definitive diagnosis may be more important to some patients than others due to differing pregnancy intent and/or desirableness. Patients may choose to take action in terms of medication or uterine aspiration based on suspicion of EPL, or they may wish to end the pregnancy regardless of EPL diagnosis.

Management options for EPL

EPL can be managed expectantly, with medication, or with uterine aspiration. These methods have different risks and benefits, and in most cases all should be made available to women who experience EPL.5-7

Expectant management

Expectant management involves waiting for the body to spontaneously expel the nonviable pregnancy. In the absence of any signs of infection, hemodynamic instability, or other medical instability, it is safe and reasonable to wait a month or more before intervening, according to patient choice. Expectant management is up to 80% effective.8

Medication management

Medication management entails using mifepristone and misoprostol, or misoprostol alone, to cause uterine contractions to expel the pregnancy. A landmark study demonstrated that medication management of EPL with the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol is significantly more effective than misoprostol alone.9 While the mean cost of mifepristone is approximately $90 per dose, its addition is cost-effective given the increased efficacy.10

The evidence-based combination regimen is to provide mifepristone 200 mg orally, followed 24 hours later by misoprostol 800 µg vaginally, for a success rate of 87.8% by 8 days, and 91.2% by 30 days posttreatment. Success rates can be increased further by adding a second dose of misoprostol to take as needed.5

We strongly recommend using the combination regimen if you have access to mifepristone. If you do not have access to mifepristone in your clinical setting, perhaps this indication for use can help facilitate getting it onto your formulary. (See “Ordering mifepristone” below.)

Without access to mifepristone, medication abortion still should be offered after discussing the decreased efficacy with patients. The first-trimester misoprostol-only regimen for EPL is to give misoprostol 800 µg buccally, vaginally, or sublingually, with a second dose if there is no effect (TABLE 4).1,5 For losses after 9 weeks, some data suggest adding additional doses of misoprostol 400 µg every 3 hours until expulsion.11

- There are 2 distributors of mifepristone in the United States. Danco (www.earlyoptionpill.com) distributes the branded Mifeprex and GenBioPro (www.genbiopro.com) distributes generic mifepristone.

- To order mifepristone, 1 health care provider from your clinic or facility must read and sign the distributor’s prescriber agreement and account setup form. These forms and instructions can be found on each distributor’s website. Future orders can be made by calling the distributor directly (Danco: 1-877-432-7596; GenBioPro: 1-855-643-3463).

- The shelf life of mifepristone is 18 months.

- Each patient who receives mifepristone needs to read and sign a patient agreement (available on distributor websites), as required by the US Food and Drug Administration–approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.

Continue to: Uterine aspiration...

Uterine aspiration

Uterine aspiration is the third management option for EPL and is virtually 100% successful. Although aspiration is used when expectant or medication management fails, it is also a first-line option based on patient choice or contraindications to the other 2 management options.

We recommend either manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) or electric vacuum aspiration (EVA); sharp curettage almost never should be used. Uterine aspiration can be performed safely in a clinic, emergency department, or operating room (OR) setting, depending on patient characteristics and desires.12-14 For various reasons, many patients prefer outpatient management. These reasons may include avoiding the costs and delays associated with OR management, wanting more control over who performs the procedure, or avoiding more significant/general anesthesia. MVA in the outpatient setting is the most cost-effective approach to uterine aspiration.15

Choosing a management approach

There are virtually no contraindications for uterine aspiration. Expectant and medication management are contraindicated (and uterine aspiration is recommended) in the setting of bleeding disorders, anticoagulation, suspected intrauterine infection, suspected molar pregnancy, significant cardiopulmonary disease, or any condition for which heavy, unsupervised bleeding might be dangerous.1 Uterine aspiration offers immediate resolution, with a procedure usually lasting 3 to 10 minutes. By contrast, expectant and medication management offer a less predictable time to resolution and, often, a more prolonged period of active pregnancy expulsion.

In the absence of a contraindication, patient choice should determine which management option is used. All 3 options are similarly safe and effective, and the differences that do exist are acceptable to patients as long as they are allowed to access their preferred EPL management method.5,6,16 Patient satisfaction is associated directly with the ability to choose the method of preference.

Managing pain

Pain management should be offered to all women diagnosed with EPL. Those who choose expectant or medication management likely will require only oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). A minority may require the addition of a small number of narcotic pain pills.17

Women who choose uterine aspiration also should be offered pain management. All patients should be given a paracervical block; other medications can include NSAIDs, an oral benzodiazepine, intravenous (IV) sedation, or even general anesthesia/monitored airway care.17

Patients’ expectations about pain management should be addressed directly during initial counseling. This may help patients decide what type of management and treatment location they might prefer.

Checking blood type: Is it necessary?

The ACOG practice bulletin for EPL states, “administration of Rh D immune globulin should be considered in cases of early pregnancy loss, especially those that are later in the first trimester.”1 A growing body of evidence indicates that Rho(D) immune globulin likely is unnecessary in early pregnancy.

A recent prospective cohort study of 42 women who were at 5 to 12 weeks’ gestation found that the fetal red blood cell concentration was below the calculated threshold for Rh sensitization.18 In light of recent evidence, the National Abortion Federation now recommends foregoing Rh testing and provision of Rh immune globulin at less than 8 weeks’ gestation for uterine aspiration and at less than 10 weeks’ gestation for medication abortion.19

We feel there is sufficient evidence to forego Rh testing in EPL at similar gestational ages, although this is not yet reflected in US societal guidelines. (It is already standard practice in some countries.) Although the risk of Rh alloimmunization is low, the risk of significant consequences in the event of Rh alloimmunization is high. Currently, it also is reasonable to continue giving Rho(D) immune globulin to Rh-negative patients who experience EPL at any gestational age. A lower dose (50 µg) is sufficient for EPL; the standard 300-µg dose also is acceptable.20

We anticipate that society and ACOG guidelines will change in the next few years as the body of evidence increases, and practice should change to reflect new guidance.

Continue to: Prophylactic antibiotics...

Prophylactic antibiotics

The risk of infection with EPL is low overall regardless of the management approach.1 Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended for patients undergoing uterine aspiration but are not necessary in the setting of expectant or medication management. We recommend prophylaxis with 1 dose of oral doxycycline 200 mg or oral azithromycin 500 mg approximately 30 minutes to 1 hour prior to uterine aspiration.21 Alternatives include 1 dose of oral metronidazole 500 mg or, if the patient is unable to take oral medications, IV cefazolin 2 g.

A multisite international randomized controlled trial concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis before uterine aspiration for EPL did not significantly reduce the risk of infection.22 However, there was a significant reduction in pelvic infection with antibiotic administration for the subgroup of women who underwent MVA, which is our recommended approach (along with EVA, and opposed to sharp curettage) for outpatient EPL management.

Follow-up after EPL

In-person follow-up after treatment of EPL is not medically necessary. A repeat ultrasonography 1 to 2 weeks after expectant or medication management can be helpful to confirm completion of the process, and clinicians should focus on presence or absence of a gestational sac to determine if further management is needed.1

Follow-up by telemedicine or phone also is an option and may be preferred in the following situations:

- the patient lives far from the clinic

- travel to the clinic is difficult or expensive

- the patient has child-care issues

- there is a global pandemic necessitating physical distancing.

If the patient’s reported history and symptoms are consistent with a completed process, no further intervention is indicated.

If ongoing EPL is a concern, ask the patient to come in for an evaluation and ultrasonography. If visiting the clinic is still a challenge, following with urine or serum human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) levels also is acceptable. Experts recommend waiting 4 weeks before expecting a negative urine HCG measurement, although up to 25% of women with a completed EPL will still have a positive test at 4 weeks.23,24

A postprocedure serum HCG is more helpful if a preprocedure HCG level already is known. Numerous studies have evaluated phone follow-up after medication abortion and it is reasonable to translate these practices to follow-up after EPL, recognizing that direct data looking at alternative EPL follow-up are much more limited.23,25-30

The benefit of HCG follow-up at a scheduled time (such as 1 week) is less clear for EPL than for medication abortion, as HCG trends are less predictable in the setting of EPL. However, if the pregnancy has passed, a significant drop in the HCG level would be expected. It is important to take into account the patient’s history and clinical symptoms and consider in-person evaluation with possible ultrasonography if there is concern that the pregnancy tissue has not passed.

Pay attention to mental health

It is critical to assess the patient’s mental and emotional health. This should be done both at the time of EPL diagnosis and management and again at follow-up. Both patients and their partners can struggle after experiencing EPL, and they may suffer from prolonged posttraumatic stress.31

Often, EPL occurs before people have shared the news about their pregnancy. This can amplify the sense of isolation and sadness many women report. Equally critical is recognizing that not all women who experience EPL grieve, and clinicians should normalize patient experiences and feelings. Provider language is important. We recommend use of these questions and phrases:

- I’m so sorry for your loss.

- How are you feeling?

- How have you been doing since I saw you last?

- Your friends/family/partner may be grieving differently or at a different pace than you—this is normal.

- Just because the EPL process is complete doesn’t necessarily mean your processing and/or grieving is over.

- Whatever you’re feeling is okay.

Continue to: Address desire for future pregnancy or contraception...

Address desire for future pregnancy or contraception

No additional workup is necessary after EPL unless a patient is experiencing recurrent pregnancy loss. We do recommend discussing plans for future conception. If a patient wants to conceive again as soon as possible, she can start trying when she feels emotionally ready (even before her next menstrual period). One study found that the ability to conceive and those pregnancy outcomes were the same when patients were randomly assigned to start trying immediately versus waiting 3 months after EPL.32

Alternatively, a patient may want to prevent pregnancy after EPL, and this information should be explicitly elicited and addressed with comprehensive contraception counseling as needed. All forms of contraception can be initiated immediately on successful management of EPL. All contraceptive methods, including an intrauterine device, can be initiated immediately following uterine aspiration.1,33,34

Patients should be reminded that if they delay contraception initiation by more than 7 days, they are potentially at risk for pregnancy.35 Most importantly, clinicians should not make assumptions about future pregnancy desires and should ask open-ended questions to provide appropriate patient counseling.

Finally, patients may feel additional anxiety in a subsequent pregnancy. It is helpful to acknowledge this and perhaps even offer earlier and more frequent visits in early pregnancy to help reduce anxiety. EPL is commonly experienced, and unfortunately it is sometimes poorly addressed by clinicians.

We hope this guidance will help you provide excellent, evidence-based, and sensitive care that will not only manage your patient’s EPL but also make the experience as positive as possible. ●

- Early pregnancy loss (EPL) is common, occurring in up to 15% to 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies.

- EPL can be managed expectantly, with medication, or by uterine aspiration.

- There are virtually no contraindications to uterine aspiration.

- Contraindications to expectant or medication management include any situation in which heavy, unsupervised bleeding might be dangerous.

- In the absence of contraindications, patient preference should dictate the management approach.

- Mifepristone-misoprostol is more effective than misoprostol alone.

- Manual uterine aspiration in the outpatient setting is the most cost-effective approach to uterine evacuation.

- Rh testing is not necessary at less than 8 weeks’ gestation if choosing uterine aspiration, or at less than 10 weeks’ gestation if choosing expectant or medication management.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated for uterine aspiration, but not for expectant or medication management.

- Ultrasonography follow-up should focus on presence or absence of gestational sac.

- There are viable telemedicine and phone follow-up options that do not require repeat ultrasonography or in-person evaluation.

- There is no need to delay future conception once EPL management is confirmed to be complete.

- It is okay to initiate any contraceptive method immediately on completed management of EPL.

- Feelings toward EPL can be complex and varied; it is helpful to normalize your patients’ experiences, ask open-ended questions, and provide support as needed.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 200: early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e197-e207.

- Clement EG, Horvath S, McAllister A, et al. The language of first-trimester nonviable pregnancy: patient-reported preferences and clarity. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:149-154.

- Ventura SJ, Curtin SC, Abma JC, et al. Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the United States, 1990-2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;60:1-21.

- Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, et al; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Multispecialty Panel on Early First Trimester Diagnosis of Miscarriage and Exclusion of a Viable Uterine Pregnancy. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1443-1451.

- Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, et al. A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:761-769.

- Nanda K, Peloggia A, Grimes D, et al. Expectant care versus surgical treatment for miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(2):CD003518.

- Neilson JP, Hickey M, Vazquez J. Medical treatment for early fetal death (less than 24 weeks). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(3):CD002253.

- Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324:873-875.

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170.

- Nagendra D, Koelper N, Loza-Avalos SE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of nonviable early pregnancy: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e201594.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Wiebe E, Janssen P. Management of spontaneous abortion in family practices and hospitals. Fam Med. 1998;30:293-296.

- Harris LH, Dalton VK, Johnson TR. Surgical management of early pregnancy failure: history, politics, and safe, cost-effective care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:445.e1-e5.

- Dalton VK, Harris L, Weisman CS, et al. Patient preferences, satisfaction, and resource use in office evacuation of early pregnancy failure. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:103-110.

- Rausch M, Lorch S, Chung K, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of surgical versus medical management of early pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:355-360.

- Trinder J, Brocklehurst P, Porter R, et al. Management of miscarriage: expectant, medical, or surgical? Results of randomised controlled trial (Miscarriage Treatment [MIST] trial). BMJ. 2006;332:1235-1240.

- Calvache JA, Delgado-Noguera MF, Lesaffre E, et al. Anaesthesia for evacuation of incomplete miscarriage. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2012(4):CD008681.

- Horvath S, Tsao P, Huang ZY, et al. The concentration of fetal red blood cells in first-trimester pregnant women undergoing uterine aspiration is below the calculated threshold for Rh sensitization. Contraception. 2020;102:1-6.

- National Abortion Federation. 2020 clinical policy guidelines for abortion care. https://www.prochoice.org/education-and-advocacy/cpg. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e59-e70.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 104: antibiotic prophylaxis for gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1180-1189.

- Lissauer D, Wilson A, Hewitt CA, et al. A randomized trial of prophylactic antibiotics for miscarriage surgery. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1012-1021.

- Perriera L, Reeves MF, Chen BA, et al. Feasibility of telephone follow-up after medical abortion. Contraception. 2010:81:143-149.

- Barnhart K, Sammel MD, Chung K, et al. Decline of serum human chorionic gonadotropin and spontaneous complete abortion: defining the normal curve. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 pt 1):975-981.

- Chen MJ, Rounds KM, Creinin MD, et al. Comparing office and telephone follow-up after medical abortion. Contraception. 2016;94:122-126.

- Clark W, Bracken H, Tanenhaus J, et al. Alternatives to a routine follow-up visit for early medical abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):264-272.

- Jackson AV, Dayananda I, Fortin JM, et al. Can women accurately assess the outcome of medical abortion based on symptoms alone? Contraception. 2012;85:192-197.

- Raymond EG, Tan YL, Grant M, et al. Self-assessment of medical abortion outcome using symptoms and home pregnancy testing. Contraception. 2018;97:324-328.

- Raymond EG, Shochet T, Bracken H. Low-sensitivity urine pregnancy testing to assess medical abortion outcome: a systematic review. Contraception. 2018;98:30-35.

- Raymond EG, Grossman D, Mark A, et al. Commentary: no-test medication abortion: a sample protocol for increasing access during a pandemic and beyond. Contraception. 2020;101:361-366.

- Farren J, Jalmbrant M, Ameye L, et al. Post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011864.

- Schliep KC, Mitchell EM, Mumford SL, et al. Trying to conceive after an early pregnancy loss: an assessment on how long couples should wait. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:204-212. DOI: 0.1097/AOG.0000000000001159.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion No. 642: increasing access to contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e44-e48.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US medical eligibility criteria (US MEC) for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 200: early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e197-e207.

- Clement EG, Horvath S, McAllister A, et al. The language of first-trimester nonviable pregnancy: patient-reported preferences and clarity. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:149-154.

- Ventura SJ, Curtin SC, Abma JC, et al. Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the United States, 1990-2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;60:1-21.

- Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, et al; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Multispecialty Panel on Early First Trimester Diagnosis of Miscarriage and Exclusion of a Viable Uterine Pregnancy. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1443-1451.

- Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, et al. A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:761-769.

- Nanda K, Peloggia A, Grimes D, et al. Expectant care versus surgical treatment for miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(2):CD003518.

- Neilson JP, Hickey M, Vazquez J. Medical treatment for early fetal death (less than 24 weeks). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(3):CD002253.

- Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324:873-875.

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170.

- Nagendra D, Koelper N, Loza-Avalos SE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of nonviable early pregnancy: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e201594.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Wiebe E, Janssen P. Management of spontaneous abortion in family practices and hospitals. Fam Med. 1998;30:293-296.

- Harris LH, Dalton VK, Johnson TR. Surgical management of early pregnancy failure: history, politics, and safe, cost-effective care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:445.e1-e5.

- Dalton VK, Harris L, Weisman CS, et al. Patient preferences, satisfaction, and resource use in office evacuation of early pregnancy failure. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:103-110.

- Rausch M, Lorch S, Chung K, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of surgical versus medical management of early pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:355-360.

- Trinder J, Brocklehurst P, Porter R, et al. Management of miscarriage: expectant, medical, or surgical? Results of randomised controlled trial (Miscarriage Treatment [MIST] trial). BMJ. 2006;332:1235-1240.

- Calvache JA, Delgado-Noguera MF, Lesaffre E, et al. Anaesthesia for evacuation of incomplete miscarriage. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2012(4):CD008681.

- Horvath S, Tsao P, Huang ZY, et al. The concentration of fetal red blood cells in first-trimester pregnant women undergoing uterine aspiration is below the calculated threshold for Rh sensitization. Contraception. 2020;102:1-6.

- National Abortion Federation. 2020 clinical policy guidelines for abortion care. https://www.prochoice.org/education-and-advocacy/cpg. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e59-e70.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 104: antibiotic prophylaxis for gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1180-1189.

- Lissauer D, Wilson A, Hewitt CA, et al. A randomized trial of prophylactic antibiotics for miscarriage surgery. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1012-1021.

- Perriera L, Reeves MF, Chen BA, et al. Feasibility of telephone follow-up after medical abortion. Contraception. 2010:81:143-149.

- Barnhart K, Sammel MD, Chung K, et al. Decline of serum human chorionic gonadotropin and spontaneous complete abortion: defining the normal curve. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 pt 1):975-981.

- Chen MJ, Rounds KM, Creinin MD, et al. Comparing office and telephone follow-up after medical abortion. Contraception. 2016;94:122-126.

- Clark W, Bracken H, Tanenhaus J, et al. Alternatives to a routine follow-up visit for early medical abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):264-272.

- Jackson AV, Dayananda I, Fortin JM, et al. Can women accurately assess the outcome of medical abortion based on symptoms alone? Contraception. 2012;85:192-197.

- Raymond EG, Tan YL, Grant M, et al. Self-assessment of medical abortion outcome using symptoms and home pregnancy testing. Contraception. 2018;97:324-328.

- Raymond EG, Shochet T, Bracken H. Low-sensitivity urine pregnancy testing to assess medical abortion outcome: a systematic review. Contraception. 2018;98:30-35.

- Raymond EG, Grossman D, Mark A, et al. Commentary: no-test medication abortion: a sample protocol for increasing access during a pandemic and beyond. Contraception. 2020;101:361-366.

- Farren J, Jalmbrant M, Ameye L, et al. Post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011864.

- Schliep KC, Mitchell EM, Mumford SL, et al. Trying to conceive after an early pregnancy loss: an assessment on how long couples should wait. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:204-212. DOI: 0.1097/AOG.0000000000001159.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion No. 642: increasing access to contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e44-e48.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US medical eligibility criteria (US MEC) for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.