User login

Addiction used to be considered a moral failing, and the family was blamed for keeping the relative with addictions sick, through behaviors labeled “codependency” and “enabling.” The opioid epidemic can take credit for putting a serious dent in these destructive and stigmatizing notions. When psychiatrists actively include families as educated treatment partners, fatalities are less likely, and the havoc created by addiction on families is mitigated.

Genes and addiction

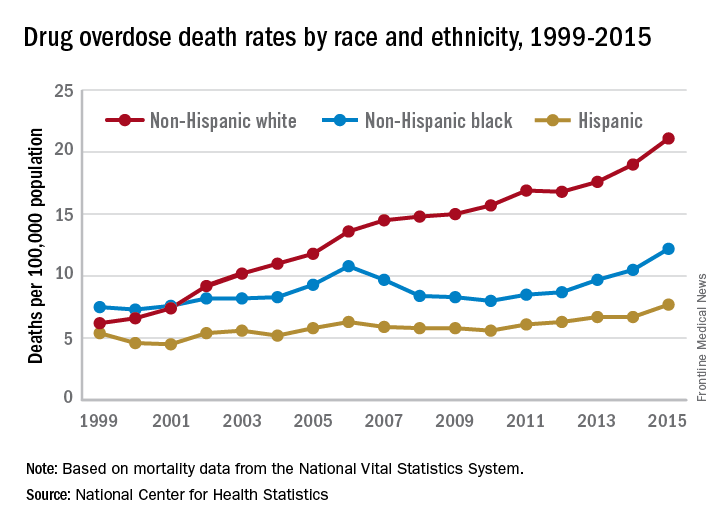

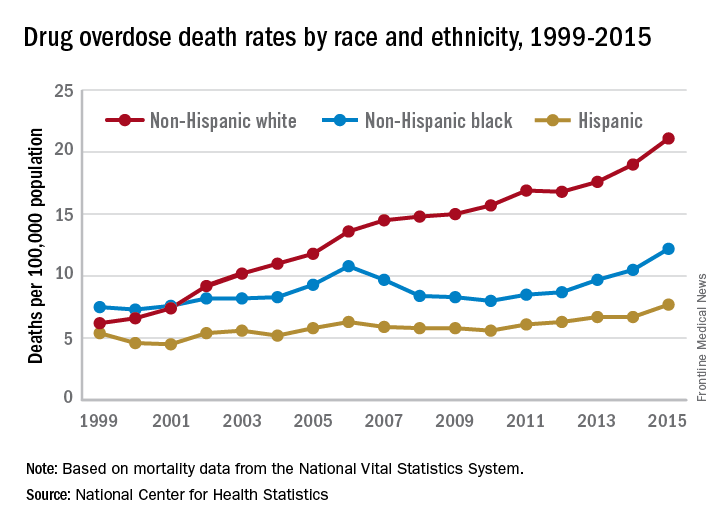

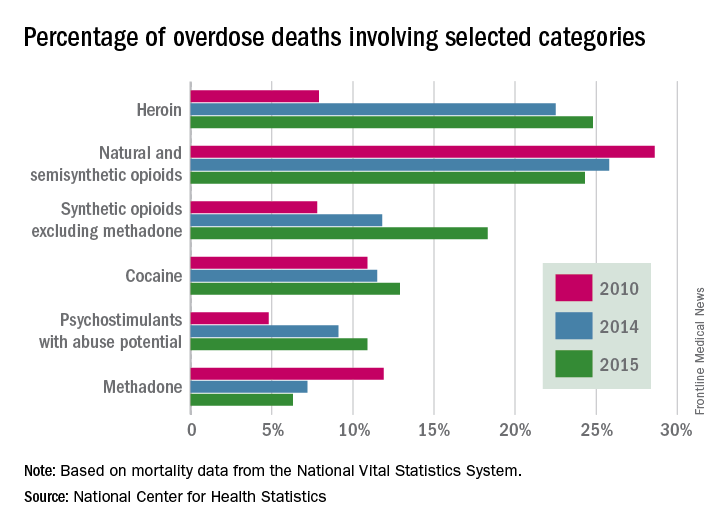

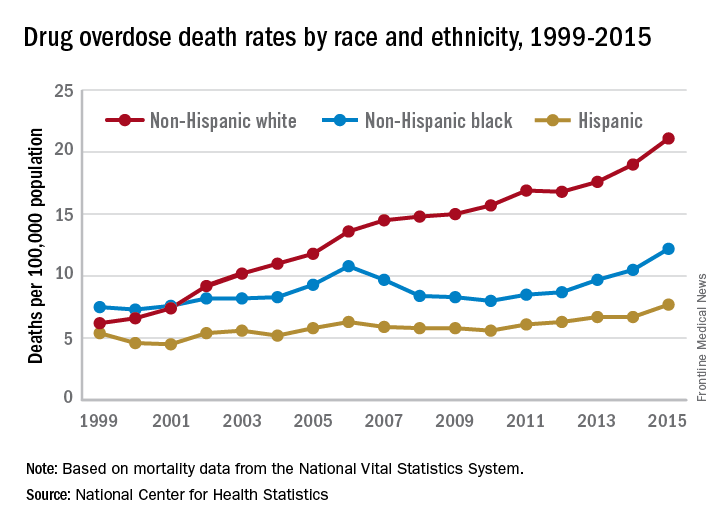

What causes addiction? Statistics show that Native Americans fare the worst of all minority groups, with death by opiates in whites and Native Americans double or triple the rates of African Americans and Latinos. Reasons put forward for Native American deaths are their vulnerability related to systemic racism, intergenerational trauma, and lack of access to health care. These “reasons” are well known to contribute to poor overall health status of impoverished communities.

Among impoverished white communities, the Monongahela Valley of Pennsylvania has been studied by Katherine McLean, PhD, as an example of postindustrial decay (Int J Drug Policy. 2016;[29]:19-26). Once a global center of steel production, the exodus of jobs, residents, and businesses since the early 1980s is thought to contribute to the high numbers of opioid deaths. A qualitative study of the people with addiction in the deteriorating mill city of McKeesport, Pa., characterized a risk environment hidden behind closed doors, and populated by unprepared, ambivalent overdose “assistants.” These people are “co-drug” users who themselves are reluctant to step forward because of fear of getting in trouble. The participants described the hopelessness and lack of opportunity as driving the use of heroin, with many stating that jobs and community reinvestment are needed to reduce fatalities. This certainly resonates with the Native American experience.

People with the AA variant of OXTR also have been shown to have less secure adult attachment and more social anxiety (World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17[1]:76-83). Comparing people with OXTR variants, the AA genotype was associated with a perceived negative social environment and significantly increased PTSD symptoms, whereas the GG genotype was protective.

However, for many decades, psychological theories about the defects of individuals and their moral failing have prevailed. In the family, aspersions have been cast on the family’s deficits in terms of setting limits and their enabling behaviors, mostly focusing on wives and mothers. The social mantra has been that since not all people get addicted, the strong resist and the weak succumb. Psychiatry has focused on providing psychotherapy to correct the personal deficits of the weak and addicted and, from a family perspective, on correcting negative personality traits in the caregivers, classified as codependency.

Roots of codependency

The concept of codependency began as a grassroots idea in the 1960s to describe family members, usually wives or mothers, who were deemed excessive in their caring for their husband or son with addiction. The term was used to describe women who had an overresponsibility for relationships, rather than a responsibility to self. Support groups for codependency, such as Co-Dependents Anonymous, Al-Anon/Alateen, Nar-Anon, and Adult Children of Alcoholics, based on the 12-step program model of Alcoholics Anonymous, were established. Codependents were negatively labeled as rescuers, supporters, and confidantes of their family member with substance use disorder. These helpers were described as dependent on the other person’s poor functioning to satisfy their own emotional needs.

In these early descriptions, there was a lack of discussion about possible deeper family dynamics: Inequality in financial independence of each partner, the desire for family stability focusing on the welfare of children, the real possibility that disrupting a relationship might result in violence if the woman was more assertive. Women were blamed for trying to love their spouse out of the addiction. One aspect of codependency is self-sacrifice, which used to be considered an important trait of the good wife but became a negative trait in the 1960s. Recovery from codependence was considered achieved when the wife or mother expressed healthy self-assertiveness. Some scholars did state, however, that they believed that codependency was not a negative trait, but rather a healthy personality trait taken to excess. In most studies, women with high codependency ratings have tended to be unemployed and with lower educations. Their behavior had been considered worthy of a DSM inclusion as a personality disorder, but luckily, this was thwarted.

A family is forced to make some accounting when an individual develops a substance use disorder. If the family tries to maintain equilibrium and keeps things as stable as possible for the sake of maintaining the family unit or the stability of the lives of the children, accommodation will be required. Accommodation minimizes the impact of the addiction: the sober spouse stepping up to complete the roles of the ill relative and in all ways reducing the impact of dysfunction on the family. If you swap out the illness and consider the ill family member as having cancer or respiratory distress, then you reframe the spouse’s “codependence” as the behavior of a caring spouse.

This long preamble is intended to illustrate how little family dynamics have to do with the etiology of addiction. Addiction is a chronic neurobiological disease, and like all diseases, individuals, and couples and families have the option of learning to cope well. We, as psychiatrists, must move away from blaming people (usually women who have less-than-optimal coping skills) and consider how best to engage partners and families in optimal programs.*

Families can benefit from specialist treatment and thus contribute to the recovery process. One example is a telepsychiatry program that aimed to improve family coping skills to cope with relatives who have substance use disorders. The Tele-intervention Model and Monitoring of Families of Drug Users is based on motivational interviewing and stages of change. Families were randomized into the intervention group (n = 163) or the usual treatment (n = 162). After 6 months of follow-up, the family members of the telepsychiatry group were twice as likely to modify their behavior (odds ratio; 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.18-3.65) (J Sub Use Misuse. 2017 Jan 28;52[2]:164-74). This model was organized so that each of nine calls had a specific goal to stimulate the family members in their process of change.

Family change and engagement also can occur through Alanon (Subst Use Misuse. 2015; 50[1]:62-71) and the use of the Arise program of Judith Landau, MD, (Landau J et al. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26[3]:379-98).

In summary, the family can be engaged in treatment and can develop family coping skills to support their relative with this chronic neurobiological disease.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

*Updated on January 12, 2018.

Addiction used to be considered a moral failing, and the family was blamed for keeping the relative with addictions sick, through behaviors labeled “codependency” and “enabling.” The opioid epidemic can take credit for putting a serious dent in these destructive and stigmatizing notions. When psychiatrists actively include families as educated treatment partners, fatalities are less likely, and the havoc created by addiction on families is mitigated.

Genes and addiction

What causes addiction? Statistics show that Native Americans fare the worst of all minority groups, with death by opiates in whites and Native Americans double or triple the rates of African Americans and Latinos. Reasons put forward for Native American deaths are their vulnerability related to systemic racism, intergenerational trauma, and lack of access to health care. These “reasons” are well known to contribute to poor overall health status of impoverished communities.

Among impoverished white communities, the Monongahela Valley of Pennsylvania has been studied by Katherine McLean, PhD, as an example of postindustrial decay (Int J Drug Policy. 2016;[29]:19-26). Once a global center of steel production, the exodus of jobs, residents, and businesses since the early 1980s is thought to contribute to the high numbers of opioid deaths. A qualitative study of the people with addiction in the deteriorating mill city of McKeesport, Pa., characterized a risk environment hidden behind closed doors, and populated by unprepared, ambivalent overdose “assistants.” These people are “co-drug” users who themselves are reluctant to step forward because of fear of getting in trouble. The participants described the hopelessness and lack of opportunity as driving the use of heroin, with many stating that jobs and community reinvestment are needed to reduce fatalities. This certainly resonates with the Native American experience.

People with the AA variant of OXTR also have been shown to have less secure adult attachment and more social anxiety (World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17[1]:76-83). Comparing people with OXTR variants, the AA genotype was associated with a perceived negative social environment and significantly increased PTSD symptoms, whereas the GG genotype was protective.

However, for many decades, psychological theories about the defects of individuals and their moral failing have prevailed. In the family, aspersions have been cast on the family’s deficits in terms of setting limits and their enabling behaviors, mostly focusing on wives and mothers. The social mantra has been that since not all people get addicted, the strong resist and the weak succumb. Psychiatry has focused on providing psychotherapy to correct the personal deficits of the weak and addicted and, from a family perspective, on correcting negative personality traits in the caregivers, classified as codependency.

Roots of codependency

The concept of codependency began as a grassroots idea in the 1960s to describe family members, usually wives or mothers, who were deemed excessive in their caring for their husband or son with addiction. The term was used to describe women who had an overresponsibility for relationships, rather than a responsibility to self. Support groups for codependency, such as Co-Dependents Anonymous, Al-Anon/Alateen, Nar-Anon, and Adult Children of Alcoholics, based on the 12-step program model of Alcoholics Anonymous, were established. Codependents were negatively labeled as rescuers, supporters, and confidantes of their family member with substance use disorder. These helpers were described as dependent on the other person’s poor functioning to satisfy their own emotional needs.

In these early descriptions, there was a lack of discussion about possible deeper family dynamics: Inequality in financial independence of each partner, the desire for family stability focusing on the welfare of children, the real possibility that disrupting a relationship might result in violence if the woman was more assertive. Women were blamed for trying to love their spouse out of the addiction. One aspect of codependency is self-sacrifice, which used to be considered an important trait of the good wife but became a negative trait in the 1960s. Recovery from codependence was considered achieved when the wife or mother expressed healthy self-assertiveness. Some scholars did state, however, that they believed that codependency was not a negative trait, but rather a healthy personality trait taken to excess. In most studies, women with high codependency ratings have tended to be unemployed and with lower educations. Their behavior had been considered worthy of a DSM inclusion as a personality disorder, but luckily, this was thwarted.

A family is forced to make some accounting when an individual develops a substance use disorder. If the family tries to maintain equilibrium and keeps things as stable as possible for the sake of maintaining the family unit or the stability of the lives of the children, accommodation will be required. Accommodation minimizes the impact of the addiction: the sober spouse stepping up to complete the roles of the ill relative and in all ways reducing the impact of dysfunction on the family. If you swap out the illness and consider the ill family member as having cancer or respiratory distress, then you reframe the spouse’s “codependence” as the behavior of a caring spouse.

This long preamble is intended to illustrate how little family dynamics have to do with the etiology of addiction. Addiction is a chronic neurobiological disease, and like all diseases, individuals, and couples and families have the option of learning to cope well. We, as psychiatrists, must move away from blaming people (usually women who have less-than-optimal coping skills) and consider how best to engage partners and families in optimal programs.*

Families can benefit from specialist treatment and thus contribute to the recovery process. One example is a telepsychiatry program that aimed to improve family coping skills to cope with relatives who have substance use disorders. The Tele-intervention Model and Monitoring of Families of Drug Users is based on motivational interviewing and stages of change. Families were randomized into the intervention group (n = 163) or the usual treatment (n = 162). After 6 months of follow-up, the family members of the telepsychiatry group were twice as likely to modify their behavior (odds ratio; 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.18-3.65) (J Sub Use Misuse. 2017 Jan 28;52[2]:164-74). This model was organized so that each of nine calls had a specific goal to stimulate the family members in their process of change.

Family change and engagement also can occur through Alanon (Subst Use Misuse. 2015; 50[1]:62-71) and the use of the Arise program of Judith Landau, MD, (Landau J et al. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26[3]:379-98).

In summary, the family can be engaged in treatment and can develop family coping skills to support their relative with this chronic neurobiological disease.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

*Updated on January 12, 2018.

Addiction used to be considered a moral failing, and the family was blamed for keeping the relative with addictions sick, through behaviors labeled “codependency” and “enabling.” The opioid epidemic can take credit for putting a serious dent in these destructive and stigmatizing notions. When psychiatrists actively include families as educated treatment partners, fatalities are less likely, and the havoc created by addiction on families is mitigated.

Genes and addiction

What causes addiction? Statistics show that Native Americans fare the worst of all minority groups, with death by opiates in whites and Native Americans double or triple the rates of African Americans and Latinos. Reasons put forward for Native American deaths are their vulnerability related to systemic racism, intergenerational trauma, and lack of access to health care. These “reasons” are well known to contribute to poor overall health status of impoverished communities.

Among impoverished white communities, the Monongahela Valley of Pennsylvania has been studied by Katherine McLean, PhD, as an example of postindustrial decay (Int J Drug Policy. 2016;[29]:19-26). Once a global center of steel production, the exodus of jobs, residents, and businesses since the early 1980s is thought to contribute to the high numbers of opioid deaths. A qualitative study of the people with addiction in the deteriorating mill city of McKeesport, Pa., characterized a risk environment hidden behind closed doors, and populated by unprepared, ambivalent overdose “assistants.” These people are “co-drug” users who themselves are reluctant to step forward because of fear of getting in trouble. The participants described the hopelessness and lack of opportunity as driving the use of heroin, with many stating that jobs and community reinvestment are needed to reduce fatalities. This certainly resonates with the Native American experience.

People with the AA variant of OXTR also have been shown to have less secure adult attachment and more social anxiety (World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17[1]:76-83). Comparing people with OXTR variants, the AA genotype was associated with a perceived negative social environment and significantly increased PTSD symptoms, whereas the GG genotype was protective.

However, for many decades, psychological theories about the defects of individuals and their moral failing have prevailed. In the family, aspersions have been cast on the family’s deficits in terms of setting limits and their enabling behaviors, mostly focusing on wives and mothers. The social mantra has been that since not all people get addicted, the strong resist and the weak succumb. Psychiatry has focused on providing psychotherapy to correct the personal deficits of the weak and addicted and, from a family perspective, on correcting negative personality traits in the caregivers, classified as codependency.

Roots of codependency

The concept of codependency began as a grassroots idea in the 1960s to describe family members, usually wives or mothers, who were deemed excessive in their caring for their husband or son with addiction. The term was used to describe women who had an overresponsibility for relationships, rather than a responsibility to self. Support groups for codependency, such as Co-Dependents Anonymous, Al-Anon/Alateen, Nar-Anon, and Adult Children of Alcoholics, based on the 12-step program model of Alcoholics Anonymous, were established. Codependents were negatively labeled as rescuers, supporters, and confidantes of their family member with substance use disorder. These helpers were described as dependent on the other person’s poor functioning to satisfy their own emotional needs.

In these early descriptions, there was a lack of discussion about possible deeper family dynamics: Inequality in financial independence of each partner, the desire for family stability focusing on the welfare of children, the real possibility that disrupting a relationship might result in violence if the woman was more assertive. Women were blamed for trying to love their spouse out of the addiction. One aspect of codependency is self-sacrifice, which used to be considered an important trait of the good wife but became a negative trait in the 1960s. Recovery from codependence was considered achieved when the wife or mother expressed healthy self-assertiveness. Some scholars did state, however, that they believed that codependency was not a negative trait, but rather a healthy personality trait taken to excess. In most studies, women with high codependency ratings have tended to be unemployed and with lower educations. Their behavior had been considered worthy of a DSM inclusion as a personality disorder, but luckily, this was thwarted.

A family is forced to make some accounting when an individual develops a substance use disorder. If the family tries to maintain equilibrium and keeps things as stable as possible for the sake of maintaining the family unit or the stability of the lives of the children, accommodation will be required. Accommodation minimizes the impact of the addiction: the sober spouse stepping up to complete the roles of the ill relative and in all ways reducing the impact of dysfunction on the family. If you swap out the illness and consider the ill family member as having cancer or respiratory distress, then you reframe the spouse’s “codependence” as the behavior of a caring spouse.

This long preamble is intended to illustrate how little family dynamics have to do with the etiology of addiction. Addiction is a chronic neurobiological disease, and like all diseases, individuals, and couples and families have the option of learning to cope well. We, as psychiatrists, must move away from blaming people (usually women who have less-than-optimal coping skills) and consider how best to engage partners and families in optimal programs.*

Families can benefit from specialist treatment and thus contribute to the recovery process. One example is a telepsychiatry program that aimed to improve family coping skills to cope with relatives who have substance use disorders. The Tele-intervention Model and Monitoring of Families of Drug Users is based on motivational interviewing and stages of change. Families were randomized into the intervention group (n = 163) or the usual treatment (n = 162). After 6 months of follow-up, the family members of the telepsychiatry group were twice as likely to modify their behavior (odds ratio; 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.18-3.65) (J Sub Use Misuse. 2017 Jan 28;52[2]:164-74). This model was organized so that each of nine calls had a specific goal to stimulate the family members in their process of change.

Family change and engagement also can occur through Alanon (Subst Use Misuse. 2015; 50[1]:62-71) and the use of the Arise program of Judith Landau, MD, (Landau J et al. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26[3]:379-98).

In summary, the family can be engaged in treatment and can develop family coping skills to support their relative with this chronic neurobiological disease.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

*Updated on January 12, 2018.