User login

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

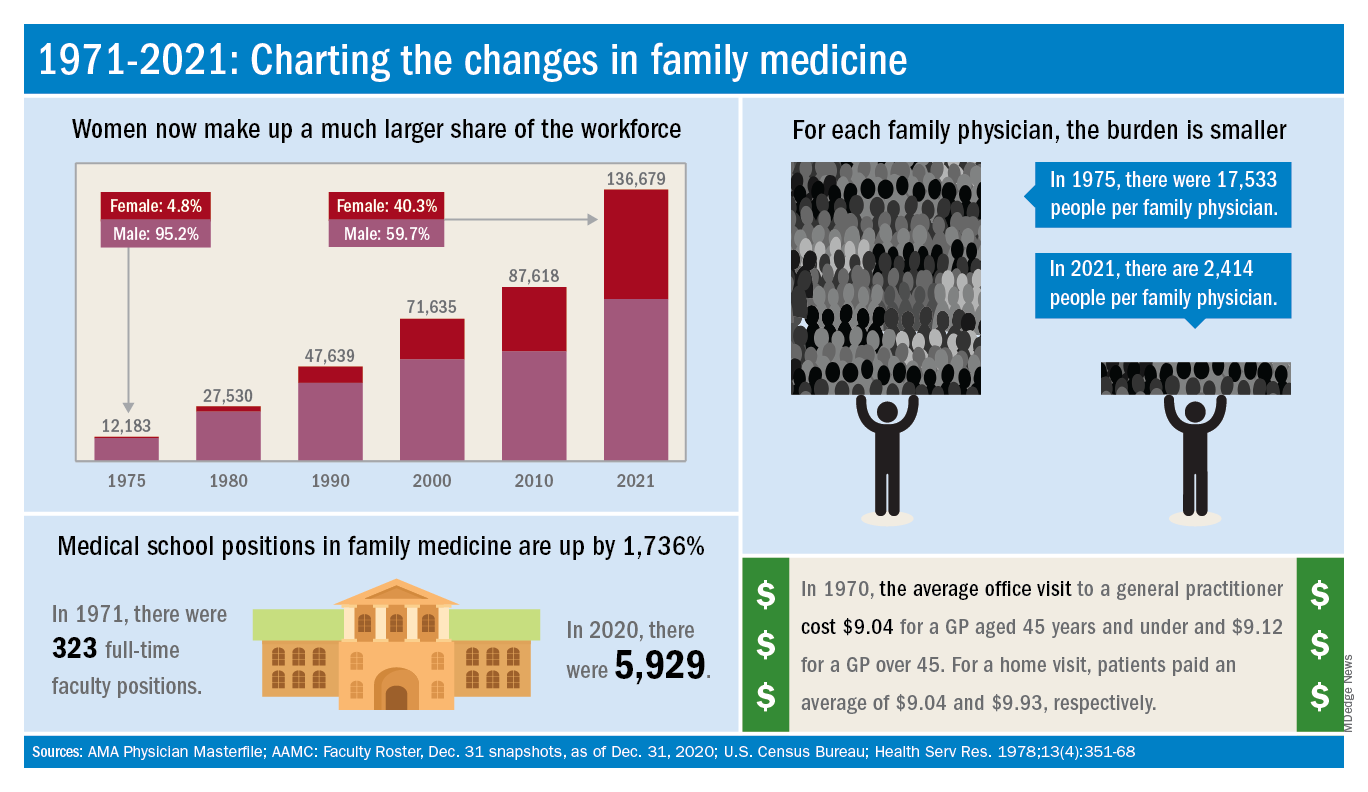

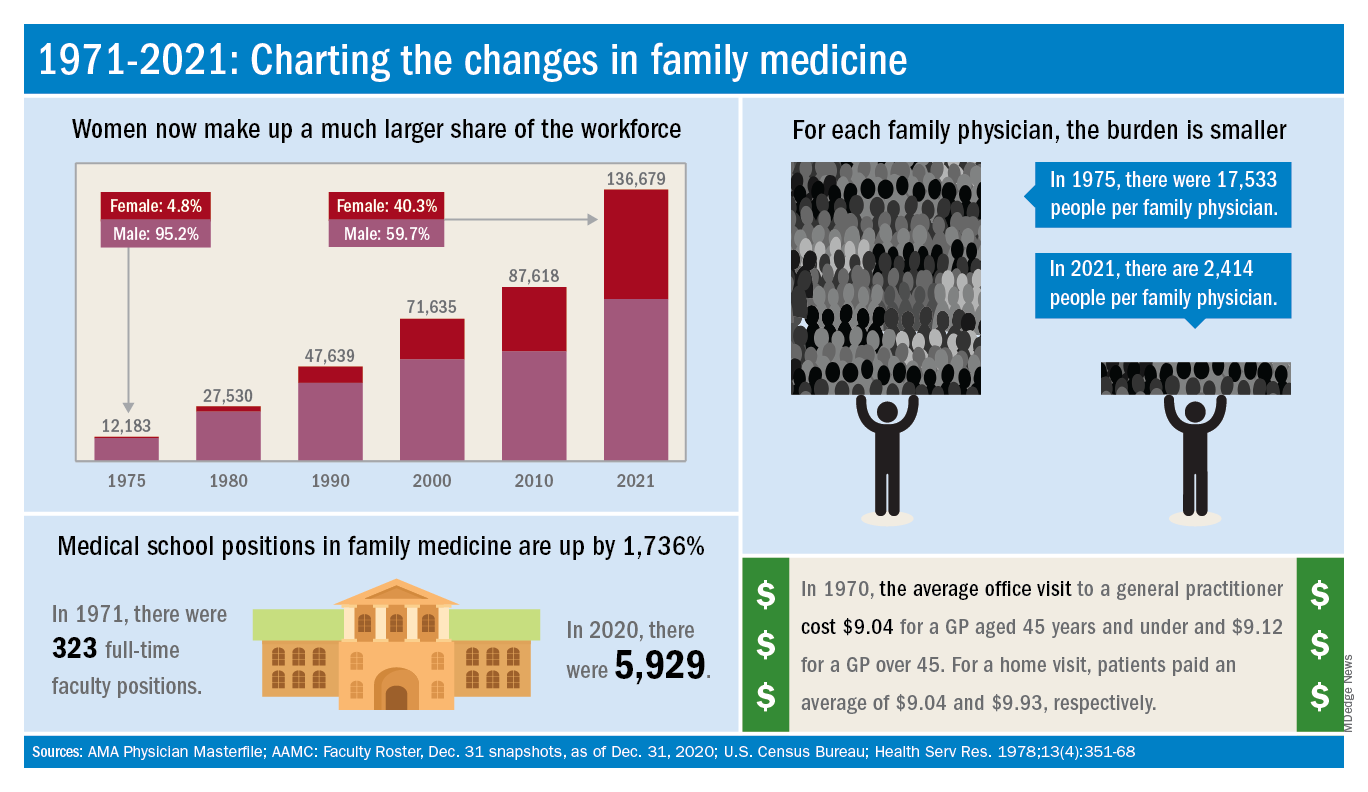

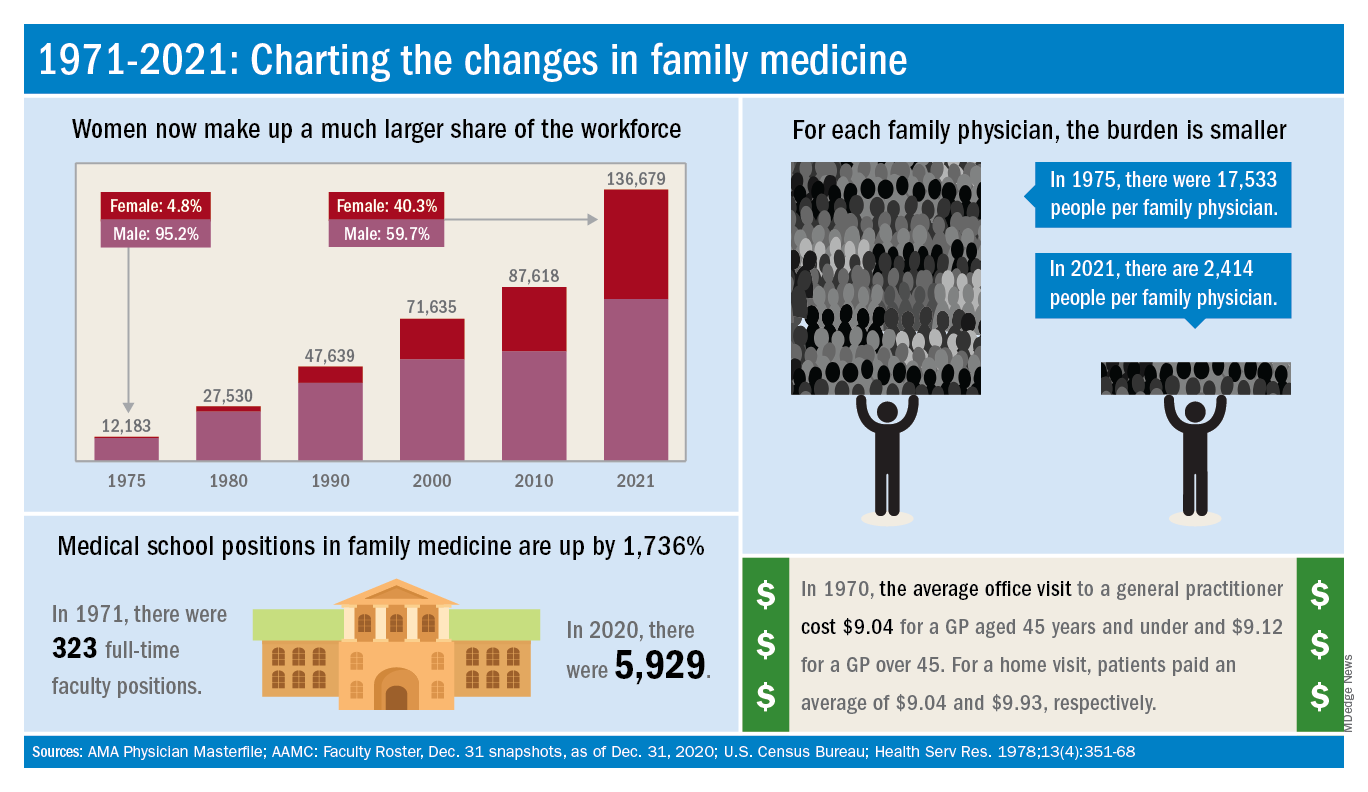

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”