User login

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised (CIWA-Ar) scale is a well-established protocol that attempts to measure the degree of alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal. The CIWA-Ar scale measures 10 domains and indexes the severity of withdrawal on a scale from 0 to 67; scores >8 are generally considered to be indicative of at least mild-to-moderate withdrawal, and scores >20 represent significant withdrawal.1 Despite its common use in many medical settings, the CIWA-Ar scale has been impugned as a less-than-reliable index of true alcohol withdrawal2 and has the potential for misuse among ordering physicians.3 In this case report, I describe a malingering patient who intentionally and successfully feigned symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, which demonstrates that the purposeful reproduction of symptoms measured by the CIWA-Ar scale can render the protocol clinically useless.

CASE REPORT

Mr. G, a 63-year-old African-American man, was admitted to the general medical floor with a chief complaint of alcohol withdrawal. He had a history of alcohol use disorder, severe, and unspecified depression. He said he had been drinking a gallon of wine plus “a fifth” of vodka every day for the past 1.5 months. More than 1 year ago, he had been admitted for alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens, but he denied having any other psychiatric history.

In the emergency department, Mr. G was given IV lorazepam, 6 mg total, for alcohol withdrawal. He was reported to be “scoring” on the CIWA-Ar scale with apparently uncontrollable tremulousness, visual hallucinations, and confusion. His vitals were within normal limits, his mean corpuscular volume and lipase level were within normal limits, and the rest of his presentation was largely unremarkable.

Once admitted to the general medical floor, he continued to receive benzodiazepines for what was documented as severe alcohol withdrawal. When clinical staff were not in the room, the patient was observed to be resting comfortably without tremulousness. When the patient was seen by the psychiatry consultation service, he produced full body tremulousness with marked shoulder and hip thrusting. His account of how much he had been drinking contradicted the amount he reported to other teams in the hospital. When the consulting psychiatrist appeared unimpressed by his full body jerking, the patient abruptly pointed to the corner of the room and yelled “What is that?” when nothing was there. When the primary medical team suggested to the patient that his vitals were within normal limits and he did not appear to be in true alcohol withdrawal, the patient escalated the degree of his full body jerking.

Over the next few days, the patient routinely would tell clinical staff “I’m having DTs.” He also specifically requested lorazepam. After consultation, the medical and psychiatry teams determined the patient was feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. The lorazepam was discontinued, and the patient was discharged home with outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

Limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale

The CIWA-Ar scale is intended to guide the need for medications, such as benzodiazepines, to help mitigate symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine treatment has been shown to be superior to fixed-schedule dosing.4 However, symptom-triggered treatment is problematic in the setting of feigned symptoms.

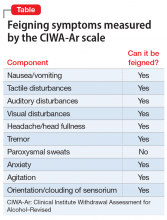

When psychiatrists and nurses calculate a CIWA-Ar score, they rely on both subjective accounts of a patient’s withdrawal severity as well as objective signs, such as vitals and a physical examination. Many of the elements included in the CIWA-Ar scale can be easily feigned (Table). Feigned alcohol withdrawal may fall into 2 categories: (1) the false reporting of subjective symptoms, and (2) the false portrayal of objective signs.

Continue to: The false reporting...

The false reporting of subjective symptoms can include the reported presence of nausea or vomiting, anxiety, tactile hallucinations, auditory hallucinations, headache or head fullness, and visual hallucinations. The false portrayal of objective signs can include the feigning of tremulousness, agitation, and confusion (eg, incorrectly answering orienting questions). In both categories, the simple presence of these signs or symptoms, whether falsely reported or falsely portrayed, would cause the patient to “score” on the CIWA-Ar scale.

Thus, the need to effectively rule out feigned symptoms is essential because inappropriate dosing of benzodiazepines can be dangerous, costly, and utilize limited hospital resources that could otherwise be diverted to a patient with a true medical or psychiatric illness. In these instances, it is crucial to pay close attention to vital signs because these are more reliable indices of withdrawal. A patient’s ability to purposefully feign symptoms of alcohol withdrawal highlights the limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale as a validated measure of alcohol withdrawal, and renders it effectively useless in the setting of either malingering or factitious disorder.

Resnick5 describes malingering as either pure malingering, partial malingering, or false imputation. Pure malingering refers to the feigning of a nonexistent disorder or illness. Partial malingering refers to the exaggeration of symptoms that are present, but to a lesser degree. False imputation refers to the attribution of symptoms from a separate disorder to one the patient knows is unrelated (eg, attributing chronic low back pain from a prior sports injury to a recent motor vehicle accident). In Mr. G’s case, he had multiple prior admissions for true, non-feigned alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens. His knowledge of the signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal therefore helped him make calculated efforts to manipulate clinical staff in his quest to obtain benzodiazepines. Whether this was pure or partial malingering remained unclear because Mr. G’s true level of withdrawal could not be adequately assessed.

Potentially serious consequences

The CIWA-Ar scale is among the most widely used scales to determine the level of alcohol withdrawal and need for subsequent benzodiazepine treatment. However, its effective use is limited because it relies on subjective symptoms and objective signs that can be easily feigned or manipulated. In the setting of malingering or factitious disorder, when a patient is feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, the CIWA-Ar scale may be rendered clinically useless. This can lead to dangerous iatrogenic adverse effects, lengthy and nontherapeutic hospital stays, and an increasing financial burden on health care systems.

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Knight E, Lappalainen L. Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised might be an unreliable tool in the management of alcohol withdrawal. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(9):691-695.

3. Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, et al. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274-279.

4. Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121.

5. Resnick PJ. The detection of malingered mental illness. Behav Sci Law. 1984;2(1):20-38.

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised (CIWA-Ar) scale is a well-established protocol that attempts to measure the degree of alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal. The CIWA-Ar scale measures 10 domains and indexes the severity of withdrawal on a scale from 0 to 67; scores >8 are generally considered to be indicative of at least mild-to-moderate withdrawal, and scores >20 represent significant withdrawal.1 Despite its common use in many medical settings, the CIWA-Ar scale has been impugned as a less-than-reliable index of true alcohol withdrawal2 and has the potential for misuse among ordering physicians.3 In this case report, I describe a malingering patient who intentionally and successfully feigned symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, which demonstrates that the purposeful reproduction of symptoms measured by the CIWA-Ar scale can render the protocol clinically useless.

CASE REPORT

Mr. G, a 63-year-old African-American man, was admitted to the general medical floor with a chief complaint of alcohol withdrawal. He had a history of alcohol use disorder, severe, and unspecified depression. He said he had been drinking a gallon of wine plus “a fifth” of vodka every day for the past 1.5 months. More than 1 year ago, he had been admitted for alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens, but he denied having any other psychiatric history.

In the emergency department, Mr. G was given IV lorazepam, 6 mg total, for alcohol withdrawal. He was reported to be “scoring” on the CIWA-Ar scale with apparently uncontrollable tremulousness, visual hallucinations, and confusion. His vitals were within normal limits, his mean corpuscular volume and lipase level were within normal limits, and the rest of his presentation was largely unremarkable.

Once admitted to the general medical floor, he continued to receive benzodiazepines for what was documented as severe alcohol withdrawal. When clinical staff were not in the room, the patient was observed to be resting comfortably without tremulousness. When the patient was seen by the psychiatry consultation service, he produced full body tremulousness with marked shoulder and hip thrusting. His account of how much he had been drinking contradicted the amount he reported to other teams in the hospital. When the consulting psychiatrist appeared unimpressed by his full body jerking, the patient abruptly pointed to the corner of the room and yelled “What is that?” when nothing was there. When the primary medical team suggested to the patient that his vitals were within normal limits and he did not appear to be in true alcohol withdrawal, the patient escalated the degree of his full body jerking.

Over the next few days, the patient routinely would tell clinical staff “I’m having DTs.” He also specifically requested lorazepam. After consultation, the medical and psychiatry teams determined the patient was feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. The lorazepam was discontinued, and the patient was discharged home with outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

Limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale

The CIWA-Ar scale is intended to guide the need for medications, such as benzodiazepines, to help mitigate symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine treatment has been shown to be superior to fixed-schedule dosing.4 However, symptom-triggered treatment is problematic in the setting of feigned symptoms.

When psychiatrists and nurses calculate a CIWA-Ar score, they rely on both subjective accounts of a patient’s withdrawal severity as well as objective signs, such as vitals and a physical examination. Many of the elements included in the CIWA-Ar scale can be easily feigned (Table). Feigned alcohol withdrawal may fall into 2 categories: (1) the false reporting of subjective symptoms, and (2) the false portrayal of objective signs.

Continue to: The false reporting...

The false reporting of subjective symptoms can include the reported presence of nausea or vomiting, anxiety, tactile hallucinations, auditory hallucinations, headache or head fullness, and visual hallucinations. The false portrayal of objective signs can include the feigning of tremulousness, agitation, and confusion (eg, incorrectly answering orienting questions). In both categories, the simple presence of these signs or symptoms, whether falsely reported or falsely portrayed, would cause the patient to “score” on the CIWA-Ar scale.

Thus, the need to effectively rule out feigned symptoms is essential because inappropriate dosing of benzodiazepines can be dangerous, costly, and utilize limited hospital resources that could otherwise be diverted to a patient with a true medical or psychiatric illness. In these instances, it is crucial to pay close attention to vital signs because these are more reliable indices of withdrawal. A patient’s ability to purposefully feign symptoms of alcohol withdrawal highlights the limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale as a validated measure of alcohol withdrawal, and renders it effectively useless in the setting of either malingering or factitious disorder.

Resnick5 describes malingering as either pure malingering, partial malingering, or false imputation. Pure malingering refers to the feigning of a nonexistent disorder or illness. Partial malingering refers to the exaggeration of symptoms that are present, but to a lesser degree. False imputation refers to the attribution of symptoms from a separate disorder to one the patient knows is unrelated (eg, attributing chronic low back pain from a prior sports injury to a recent motor vehicle accident). In Mr. G’s case, he had multiple prior admissions for true, non-feigned alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens. His knowledge of the signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal therefore helped him make calculated efforts to manipulate clinical staff in his quest to obtain benzodiazepines. Whether this was pure or partial malingering remained unclear because Mr. G’s true level of withdrawal could not be adequately assessed.

Potentially serious consequences

The CIWA-Ar scale is among the most widely used scales to determine the level of alcohol withdrawal and need for subsequent benzodiazepine treatment. However, its effective use is limited because it relies on subjective symptoms and objective signs that can be easily feigned or manipulated. In the setting of malingering or factitious disorder, when a patient is feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, the CIWA-Ar scale may be rendered clinically useless. This can lead to dangerous iatrogenic adverse effects, lengthy and nontherapeutic hospital stays, and an increasing financial burden on health care systems.

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised (CIWA-Ar) scale is a well-established protocol that attempts to measure the degree of alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal. The CIWA-Ar scale measures 10 domains and indexes the severity of withdrawal on a scale from 0 to 67; scores >8 are generally considered to be indicative of at least mild-to-moderate withdrawal, and scores >20 represent significant withdrawal.1 Despite its common use in many medical settings, the CIWA-Ar scale has been impugned as a less-than-reliable index of true alcohol withdrawal2 and has the potential for misuse among ordering physicians.3 In this case report, I describe a malingering patient who intentionally and successfully feigned symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, which demonstrates that the purposeful reproduction of symptoms measured by the CIWA-Ar scale can render the protocol clinically useless.

CASE REPORT

Mr. G, a 63-year-old African-American man, was admitted to the general medical floor with a chief complaint of alcohol withdrawal. He had a history of alcohol use disorder, severe, and unspecified depression. He said he had been drinking a gallon of wine plus “a fifth” of vodka every day for the past 1.5 months. More than 1 year ago, he had been admitted for alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens, but he denied having any other psychiatric history.

In the emergency department, Mr. G was given IV lorazepam, 6 mg total, for alcohol withdrawal. He was reported to be “scoring” on the CIWA-Ar scale with apparently uncontrollable tremulousness, visual hallucinations, and confusion. His vitals were within normal limits, his mean corpuscular volume and lipase level were within normal limits, and the rest of his presentation was largely unremarkable.

Once admitted to the general medical floor, he continued to receive benzodiazepines for what was documented as severe alcohol withdrawal. When clinical staff were not in the room, the patient was observed to be resting comfortably without tremulousness. When the patient was seen by the psychiatry consultation service, he produced full body tremulousness with marked shoulder and hip thrusting. His account of how much he had been drinking contradicted the amount he reported to other teams in the hospital. When the consulting psychiatrist appeared unimpressed by his full body jerking, the patient abruptly pointed to the corner of the room and yelled “What is that?” when nothing was there. When the primary medical team suggested to the patient that his vitals were within normal limits and he did not appear to be in true alcohol withdrawal, the patient escalated the degree of his full body jerking.

Over the next few days, the patient routinely would tell clinical staff “I’m having DTs.” He also specifically requested lorazepam. After consultation, the medical and psychiatry teams determined the patient was feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. The lorazepam was discontinued, and the patient was discharged home with outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

Limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale

The CIWA-Ar scale is intended to guide the need for medications, such as benzodiazepines, to help mitigate symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine treatment has been shown to be superior to fixed-schedule dosing.4 However, symptom-triggered treatment is problematic in the setting of feigned symptoms.

When psychiatrists and nurses calculate a CIWA-Ar score, they rely on both subjective accounts of a patient’s withdrawal severity as well as objective signs, such as vitals and a physical examination. Many of the elements included in the CIWA-Ar scale can be easily feigned (Table). Feigned alcohol withdrawal may fall into 2 categories: (1) the false reporting of subjective symptoms, and (2) the false portrayal of objective signs.

Continue to: The false reporting...

The false reporting of subjective symptoms can include the reported presence of nausea or vomiting, anxiety, tactile hallucinations, auditory hallucinations, headache or head fullness, and visual hallucinations. The false portrayal of objective signs can include the feigning of tremulousness, agitation, and confusion (eg, incorrectly answering orienting questions). In both categories, the simple presence of these signs or symptoms, whether falsely reported or falsely portrayed, would cause the patient to “score” on the CIWA-Ar scale.

Thus, the need to effectively rule out feigned symptoms is essential because inappropriate dosing of benzodiazepines can be dangerous, costly, and utilize limited hospital resources that could otherwise be diverted to a patient with a true medical or psychiatric illness. In these instances, it is crucial to pay close attention to vital signs because these are more reliable indices of withdrawal. A patient’s ability to purposefully feign symptoms of alcohol withdrawal highlights the limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale as a validated measure of alcohol withdrawal, and renders it effectively useless in the setting of either malingering or factitious disorder.

Resnick5 describes malingering as either pure malingering, partial malingering, or false imputation. Pure malingering refers to the feigning of a nonexistent disorder or illness. Partial malingering refers to the exaggeration of symptoms that are present, but to a lesser degree. False imputation refers to the attribution of symptoms from a separate disorder to one the patient knows is unrelated (eg, attributing chronic low back pain from a prior sports injury to a recent motor vehicle accident). In Mr. G’s case, he had multiple prior admissions for true, non-feigned alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens. His knowledge of the signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal therefore helped him make calculated efforts to manipulate clinical staff in his quest to obtain benzodiazepines. Whether this was pure or partial malingering remained unclear because Mr. G’s true level of withdrawal could not be adequately assessed.

Potentially serious consequences

The CIWA-Ar scale is among the most widely used scales to determine the level of alcohol withdrawal and need for subsequent benzodiazepine treatment. However, its effective use is limited because it relies on subjective symptoms and objective signs that can be easily feigned or manipulated. In the setting of malingering or factitious disorder, when a patient is feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, the CIWA-Ar scale may be rendered clinically useless. This can lead to dangerous iatrogenic adverse effects, lengthy and nontherapeutic hospital stays, and an increasing financial burden on health care systems.

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Knight E, Lappalainen L. Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised might be an unreliable tool in the management of alcohol withdrawal. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(9):691-695.

3. Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, et al. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274-279.

4. Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121.

5. Resnick PJ. The detection of malingered mental illness. Behav Sci Law. 1984;2(1):20-38.

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Knight E, Lappalainen L. Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised might be an unreliable tool in the management of alcohol withdrawal. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(9):691-695.

3. Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, et al. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274-279.

4. Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121.

5. Resnick PJ. The detection of malingered mental illness. Behav Sci Law. 1984;2(1):20-38.