User login

The increasing number and efficacy of chemotherapy drugs for a host of cancers – coupled with growth of the older population – not only means that elderly patients have more options for treatment, but also that more of these patients, even among the older old, can be considered candidates for chemotherapy.

This marks a big shift in the way that oncologists approach cancer treatment for patients of advanced age. Until recently, palliative care was the only treatment offered, according to interviews with leaders in geriatric oncology.

"Starting in the mid-1980s, people began to talk about these issues and the need for data and information. Just talking about it began to raise the consciousness that age was not a contraindication per se," said Dr. James S. Goodwin, director of the Sealy Center on Aging at the University of Texas at Galveston.

The numbers are clear: The baby boom is about to turn into a geriatric blast for oncologists. In 2050, the number of Americans aged 65 and older is projected to be 88.5 million, more than double the 40.2 million projected today, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In addition, total cancer incidence is projected to increase by approximately 45%, from 1.6 million this year to 2.3 million in 2030. A 67% increase in cancer incidence is anticipated for older adults (J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:2758-65).

With more people living longer, some say the expansion has already begun. "Oncologists are seeing these patients in everyday practice," observed Dr. Arti Hurria, director of the Cancer and Aging Research Program at City of Hope in Duarte, Calif.

But defining these patients is turning out to be a challenge for geriatric oncologists, and determining the best treatment can be even more difficult.

How Old Is Old?

It’s not clear what "geriatric" means in this context. Intuitively, most people have a mental picture but putting it into words – or finding an agreed-upon age cutoff – is a bit elusive.

"Chronologic age doesn’t equal functional age," said Dr. Hurria An individual can be quite healthy at 80 years with little comorbidity; alternatively a 50-year-old with several health conditions can be quite sick. "In our research studies, we’ve really been forced to have to think about some sort of chronologic cutoff."

Age 65 has frequently been used because historically it’s a time when people retire and become eligible for benefits in the United States, she explained. But many facets of aging appear after age 70, and using data from a study of 500 cancer patients at least 65 years of age, Dr. Hurria and her colleagues found age 73 to be a good cutoff.

"In some ways, that was very reassuring because it really added evidence to our feeling that the seventh decade of life is a time when people become more vulnerable," she said. "It also happens to be a group – age 73 or 75 and older – that has been very underrepresented in clinical trials."

That’s not to say that everyone in their mid-70s or older is feeble and in poor health. Instead, it signals the need for further evaluation of an individual’s physiologic status. "From an epidemiologic point of view, what happens in the 70s is that a lot of people start developing health problems," said Dr. Martine Extermann, who has developed an instrument for evaluation of these patients and is professor of oncology at the University of South Florida and attending physician at Moffitt Cancer Center, in Tampa.

For Dr. Goodwin, the cutoff can be even higher. "People live 10 years longer today on average than when I graduated from medical school," said Dr. Goodwin. "So whatever idea we have about what an old person is, needs to be shifted up by 10 years."

In conversations about geriatric oncology with oncologists, he tends to start at age 80. "If you say 80 and older, you can let age be the factor," he explained. "Age is a very strong predictor of health and mortality. You can’t make that go away by factoring in all of the measurements that you might make about how well they function or how fast they walk."

Dr. Hurria said she likens geriatric oncology to pediatric oncology, a specialty that is also defined by age. The term geriatric oncology "highlights that there is a segment of the population that is potentially vulnerable because of things other than chronologic age. ... We also need to develop an evidence base."

"The definition of geriatric oncology is that we have a population, in which we need to do additional screening and evaluation in order to give the proper treatment," agreed Dr. Extermann, professor of oncology and internal medicine at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa.

Who Needs an In-Depth Assessment?

If not all older patients are especially vulnerable, the challenge becomes determining which patients need extra attention. The following two-tiered approach to the evaluation and management of geriatric oncology patients would divide the elderly into two groups (Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005;55:241-52):

• The first step would be to screen all older patients for vulnerability to stressors – such as chemotherapy. This should include the assessment of nutritional status, performance status, psychological state (depression), cognition, daily activity, and comorbidities. Those who are considered fit would be managed like younger patients.

• Next, frailer patients would undergo a more thorough evaluation – a comprehensive geriatric assessment – so that an optimal treatment plan could be created. The in-depth evaluation would look at an elderly person’s functional ability, physical health, cognitive and mental health, and socioenvironmental situation.

With the two-tier evaluation, "the idea is that we need a more integrated approach that is going to include a good geriatric evaluation," said Dr. Extermann, a member of the task force that proposed the approach. The ultimate goal is to match the treatment to the patient and the cancer.

In a large academic setting, a multidisciplinary team can do a more in-depth screening if necessary, she added. For private practice oncologists, the initial evaluation may indicate which patients should be referred for special care.

Where Are the Clinical Trial Data?

Another hurdle in geriatric oncology is the need for more clinical trial data that include this patient population. It’s estimated by the National Cancer Institute that more than 60% of new cancer cases occur among the elderly, but they account for about a quarter of the patients enrolled in randomized clinical trials.

"As the population is aging and most of our patients are older adults, what we’re realizing is that the inclusion criteria for those trials [in the past] did not necessarily reflect the patient who’s sitting in front of us in daily practice," Dr. Hurria said.

Although there are exceptions (notably, recent trials assessing a carboplatin-paclitaxel regimen for non–small-cell lung cancer and the VISTA [Velcade as Initial Standard Therapy for Multiple Myeloma] regimen), the lack of data on the efficacy and safety of chemotherapy regimens in the elderly has left most oncologists to rely on their own judgment.

"There is a need to develop trials for patients who might not be fit enough to participate in standard clinical trials. We still realize that there is an evidence base that we need for those patients," she said.

Research in geriatric oncology has become a priority for several organizations, among them the Geriatric Oncology Consortium and the International Society of Geriatric Oncology.

Chemotoxicity Risk

A prominent area of geriatric oncology research is the assessment of chemotoxicity in an older patient population. Dr. Extermann and Dr. Hurria each presented data at this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology on the development of risk models/scores to assess an older patient’s risk of developing chemotoxicity.

Despite her experience in geriatric oncology, Dr. Extermann was surprised to find that sometimes her opinion of a patient could be widely divergent from that of the scoring tool she developed. In other cases, "when I was sitting on the fence about whether or not to treat a patient, the score helped me decide," she said.

"It’s also very important to realize that having one such toxicity does not necessarily make the patient sick," she noted. Usually toxicities lead to some modification of the treatment. So while greater risk of chemotoxicities may look foreboding, patients are often able to tolerate the regimen with modification and can function with some help.

It’s not just a question of tolerating classic chemotoxicities, however. "If they’re already having trouble getting around their apartment and they fell once a year ago ... any kind of assault on the body may lead to a decompensation," said Dr. Goodwin.

The CARG Chemotoxicity Risk Score

Dr. Hurria and her coinvestigators followed 500 cancer patients 65 years and older throughout chemotherapy to find factors predictive of chemotoxicity, and used their findings to develop the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) Chemotoxicity Risk Score.

Age, cancer type, chemotherapy dose, number of chemotherapy drugs, anemia, and low creatinine clearance were among 11 key factors identified by the study. The rest were based on the answers to five key questions assessing various geriatric measures: self-rated hearing, number of falls in the last 6 months, need for help in taking medications, ability to walk one block, and level of social activities.

Dr. Hurria reported a significant association between the patients’ baseline risk scores and their subsequent risk of grade 3-5 chemotherapy toxicity. Those with a score greater than 12 had an 83% overall risk of grade 3-5 toxicity,compared with 27% for those with a score of 0-5. The investigators divided the study population into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk categories based on the scores.

Cancer patients 65 years and older were eligible for the study, if they were going to start a new chemotherapy regimen. Geriatric assessment began prior to the start of treatment.

Mean patient age was 73 years, 85% were white, and 56% were women. Nearly two-thirds had stage IV disease, and 70% were on polychemotherapy. In all, 53% had grade 3-5 toxicities due to chemotherapy – of these, 26% had hematologic and 43% had nonhematologic toxicities. The majority of toxicities were grade 3

The study captured laboratory values, documented the chemotherapy the patient underwent – the number of drugs, normal or modified dosing, first-line therapy or other – and asked a host of questions in a geriatric assessment that included:

• Functional status (Activities of Daily Living, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living [IADL], Karnofsky Performance Rating Scale, timed up-and-go test [time needed to rise from a chair and start walking], the number of falls in the last 6 months).

• Comorbidity.

• Cognition (Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test).

• Psychological state (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale).

• Social functioning (Medical Outcomes Study Social Activity Limitations Measure).

• Social support (Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, Seeman and Berkman Social Ties).

• Nutritional status (body mass index, percentage unintentional weight loss in the last 6 months).

"We really looked at what are the factors – other than chronologic age – that can tell us about this individual," said Dr. Hurria.

Two physicians graded chemotherapy toxicities using the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (v3.0) to determine whether the event was due to disease or chemotherapy. Patients were followed until the end of the regimen.

"We felt that in order for a measure to be utilized in clinical practice, we would need to increase both the ease of administration and the ease of the scoring by having health care providers be able to ask single questions to the patient in order to assess their risk," she said.

Therefore, the researchers developed the scoring algorithm, assigning points to each risk factor, and then used the whole cohort to determine how total score relates to chemotoxicity risk.

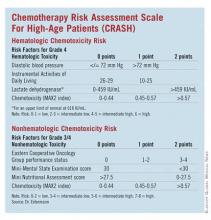

The CRASH Score

Developed by Dr. Extermann and her coinvestigators, the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score also evaluates an elderly patient’s risk for grade 4 hematologic and grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicities during chemotherapy.

"This score is helping define – a priori – the level of risk that a patient has for side effects. This way, we know how closely we need to watch the patient during chemotherapy, what strength of chemotherapy we should give, or if we should give chemotherapy at all," said Dr. Extermann.

Investigators enrolled patients from the Moffitt Cancer Center and six community centers. The process included a baseline assessment within 2 weeks of starting chemotherapy and weekly complete blood cell counts. Any published chemotherapy regimen could be used, and clinicians were free to manage care without restriction.

Toxicity was prospectively evaluated using the MAX2 index, previously developed by Dr. Extermann and her coinvestigators. Patients with dementia or planned concomitant radiotherapy were excluded.

A total of 518 patients were included in the analysis. The median age was 76 years. In all, 23 tumor types, and 111 chemotherapy regimens were included. Almost a third of patients (32%) had grade 4 hematologic toxicities, 56% had grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicity, and 68% had a combination. The median time to first toxicity was 22 days. Development of the model was based on two-thirds of the patient population, and validation on the remaining third.

The study followed patients through the course of chemotherapy up to 1 month after the last cycle. If chemotherapy continued beyond 6 months, assessment was ended at 6 months. The primary end point was the first occurrence of a grade 4 hematologic toxicity and/or a grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicity.

The researchers assessed several independent variables, including age, sex, body mass index, diastolic blood pressure, comorbidities (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics [CIRS-G]), CBC count, liver test results, creatinine clearance, albumin level, self-rated health, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) score, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) results, Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) results, cancer stage, marrow invasion, pretreatment with chemotherapy, tumor response, and chemotoxicity (MAX2 index).

Dr. Extermann noted that other research has suggested that grade 4 hematologic toxicities and grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicities have different predictors. And her group found:

• On univariate analysis for predictors of hematologic toxicities, diastolic blood pressure, albumin, lactate dehydrogenase, and IADL were significant (after adjustment for chemotoxicity).

• ECOG Performance Status, hemoglobin, creatinine clearance, albumin, MMSE, self-rated health, MNA, and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics severity index were significant predictors of nonhematologic toxicities.

The researchers then developed a scoring system for predicting hematologic and nonhematologic chemotoxicity. Scores from both subscales are totaled, and patients with a score of 0-3 are considered low risk while those with a score of 4-6 are grouped as intermediate low risk and those with 7-9 are intermediate high risk. Patients with a score greater than 9 are considered high risk.

A Young Field Looks Ahead

Dr. Extermann is planning to extend her scoring tool to include chemoradiation therapy. The score will also need to be validated for specific tumor types, and she would like to assess what happens once a patient has a severe toxicity. What predicts that they are going to have another one? Another question is whether a score can help identify a starting chemotherapy dose.

Dr. Hurria plans to validate her group’s model in a larger group of patients. It also needs to be validated for patients with specific cancers, such as breast or prostate. This could provide an evidence base to identify specific interventions to reduce or prevent severe chemotoxicities. Work also needs to be done on the pharmacology of chemotherapy drugs and how the pharmacology changes with the aging process.

No less important will be gaining insight into the decision making process as more choices become available to the elderly, she added. How can an oncologist understand what’s meaningful to the patient choosing among options? What’s the best way to communicate with this growing patient group?

Dr. Extermann reported that she has received honoraria from Amgen Inc. Dr. Hurria reported that she has significant financial relationships with Amgen, Genentech Inc., Abraxis BioScience Inc., and Pfizer Inc.

The increasing number and efficacy of chemotherapy drugs for a host of cancers – coupled with growth of the older population – not only means that elderly patients have more options for treatment, but also that more of these patients, even among the older old, can be considered candidates for chemotherapy.

This marks a big shift in the way that oncologists approach cancer treatment for patients of advanced age. Until recently, palliative care was the only treatment offered, according to interviews with leaders in geriatric oncology.

"Starting in the mid-1980s, people began to talk about these issues and the need for data and information. Just talking about it began to raise the consciousness that age was not a contraindication per se," said Dr. James S. Goodwin, director of the Sealy Center on Aging at the University of Texas at Galveston.

The numbers are clear: The baby boom is about to turn into a geriatric blast for oncologists. In 2050, the number of Americans aged 65 and older is projected to be 88.5 million, more than double the 40.2 million projected today, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In addition, total cancer incidence is projected to increase by approximately 45%, from 1.6 million this year to 2.3 million in 2030. A 67% increase in cancer incidence is anticipated for older adults (J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:2758-65).

With more people living longer, some say the expansion has already begun. "Oncologists are seeing these patients in everyday practice," observed Dr. Arti Hurria, director of the Cancer and Aging Research Program at City of Hope in Duarte, Calif.

But defining these patients is turning out to be a challenge for geriatric oncologists, and determining the best treatment can be even more difficult.

How Old Is Old?

It’s not clear what "geriatric" means in this context. Intuitively, most people have a mental picture but putting it into words – or finding an agreed-upon age cutoff – is a bit elusive.

"Chronologic age doesn’t equal functional age," said Dr. Hurria An individual can be quite healthy at 80 years with little comorbidity; alternatively a 50-year-old with several health conditions can be quite sick. "In our research studies, we’ve really been forced to have to think about some sort of chronologic cutoff."

Age 65 has frequently been used because historically it’s a time when people retire and become eligible for benefits in the United States, she explained. But many facets of aging appear after age 70, and using data from a study of 500 cancer patients at least 65 years of age, Dr. Hurria and her colleagues found age 73 to be a good cutoff.

"In some ways, that was very reassuring because it really added evidence to our feeling that the seventh decade of life is a time when people become more vulnerable," she said. "It also happens to be a group – age 73 or 75 and older – that has been very underrepresented in clinical trials."

That’s not to say that everyone in their mid-70s or older is feeble and in poor health. Instead, it signals the need for further evaluation of an individual’s physiologic status. "From an epidemiologic point of view, what happens in the 70s is that a lot of people start developing health problems," said Dr. Martine Extermann, who has developed an instrument for evaluation of these patients and is professor of oncology at the University of South Florida and attending physician at Moffitt Cancer Center, in Tampa.

For Dr. Goodwin, the cutoff can be even higher. "People live 10 years longer today on average than when I graduated from medical school," said Dr. Goodwin. "So whatever idea we have about what an old person is, needs to be shifted up by 10 years."

In conversations about geriatric oncology with oncologists, he tends to start at age 80. "If you say 80 and older, you can let age be the factor," he explained. "Age is a very strong predictor of health and mortality. You can’t make that go away by factoring in all of the measurements that you might make about how well they function or how fast they walk."

Dr. Hurria said she likens geriatric oncology to pediatric oncology, a specialty that is also defined by age. The term geriatric oncology "highlights that there is a segment of the population that is potentially vulnerable because of things other than chronologic age. ... We also need to develop an evidence base."

"The definition of geriatric oncology is that we have a population, in which we need to do additional screening and evaluation in order to give the proper treatment," agreed Dr. Extermann, professor of oncology and internal medicine at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa.

Who Needs an In-Depth Assessment?

If not all older patients are especially vulnerable, the challenge becomes determining which patients need extra attention. The following two-tiered approach to the evaluation and management of geriatric oncology patients would divide the elderly into two groups (Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005;55:241-52):

• The first step would be to screen all older patients for vulnerability to stressors – such as chemotherapy. This should include the assessment of nutritional status, performance status, psychological state (depression), cognition, daily activity, and comorbidities. Those who are considered fit would be managed like younger patients.

• Next, frailer patients would undergo a more thorough evaluation – a comprehensive geriatric assessment – so that an optimal treatment plan could be created. The in-depth evaluation would look at an elderly person’s functional ability, physical health, cognitive and mental health, and socioenvironmental situation.

With the two-tier evaluation, "the idea is that we need a more integrated approach that is going to include a good geriatric evaluation," said Dr. Extermann, a member of the task force that proposed the approach. The ultimate goal is to match the treatment to the patient and the cancer.

In a large academic setting, a multidisciplinary team can do a more in-depth screening if necessary, she added. For private practice oncologists, the initial evaluation may indicate which patients should be referred for special care.

Where Are the Clinical Trial Data?

Another hurdle in geriatric oncology is the need for more clinical trial data that include this patient population. It’s estimated by the National Cancer Institute that more than 60% of new cancer cases occur among the elderly, but they account for about a quarter of the patients enrolled in randomized clinical trials.

"As the population is aging and most of our patients are older adults, what we’re realizing is that the inclusion criteria for those trials [in the past] did not necessarily reflect the patient who’s sitting in front of us in daily practice," Dr. Hurria said.

Although there are exceptions (notably, recent trials assessing a carboplatin-paclitaxel regimen for non–small-cell lung cancer and the VISTA [Velcade as Initial Standard Therapy for Multiple Myeloma] regimen), the lack of data on the efficacy and safety of chemotherapy regimens in the elderly has left most oncologists to rely on their own judgment.

"There is a need to develop trials for patients who might not be fit enough to participate in standard clinical trials. We still realize that there is an evidence base that we need for those patients," she said.

Research in geriatric oncology has become a priority for several organizations, among them the Geriatric Oncology Consortium and the International Society of Geriatric Oncology.

Chemotoxicity Risk

A prominent area of geriatric oncology research is the assessment of chemotoxicity in an older patient population. Dr. Extermann and Dr. Hurria each presented data at this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology on the development of risk models/scores to assess an older patient’s risk of developing chemotoxicity.

Despite her experience in geriatric oncology, Dr. Extermann was surprised to find that sometimes her opinion of a patient could be widely divergent from that of the scoring tool she developed. In other cases, "when I was sitting on the fence about whether or not to treat a patient, the score helped me decide," she said.

"It’s also very important to realize that having one such toxicity does not necessarily make the patient sick," she noted. Usually toxicities lead to some modification of the treatment. So while greater risk of chemotoxicities may look foreboding, patients are often able to tolerate the regimen with modification and can function with some help.

It’s not just a question of tolerating classic chemotoxicities, however. "If they’re already having trouble getting around their apartment and they fell once a year ago ... any kind of assault on the body may lead to a decompensation," said Dr. Goodwin.

The CARG Chemotoxicity Risk Score

Dr. Hurria and her coinvestigators followed 500 cancer patients 65 years and older throughout chemotherapy to find factors predictive of chemotoxicity, and used their findings to develop the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) Chemotoxicity Risk Score.

Age, cancer type, chemotherapy dose, number of chemotherapy drugs, anemia, and low creatinine clearance were among 11 key factors identified by the study. The rest were based on the answers to five key questions assessing various geriatric measures: self-rated hearing, number of falls in the last 6 months, need for help in taking medications, ability to walk one block, and level of social activities.

Dr. Hurria reported a significant association between the patients’ baseline risk scores and their subsequent risk of grade 3-5 chemotherapy toxicity. Those with a score greater than 12 had an 83% overall risk of grade 3-5 toxicity,compared with 27% for those with a score of 0-5. The investigators divided the study population into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk categories based on the scores.

Cancer patients 65 years and older were eligible for the study, if they were going to start a new chemotherapy regimen. Geriatric assessment began prior to the start of treatment.

Mean patient age was 73 years, 85% were white, and 56% were women. Nearly two-thirds had stage IV disease, and 70% were on polychemotherapy. In all, 53% had grade 3-5 toxicities due to chemotherapy – of these, 26% had hematologic and 43% had nonhematologic toxicities. The majority of toxicities were grade 3

The study captured laboratory values, documented the chemotherapy the patient underwent – the number of drugs, normal or modified dosing, first-line therapy or other – and asked a host of questions in a geriatric assessment that included:

• Functional status (Activities of Daily Living, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living [IADL], Karnofsky Performance Rating Scale, timed up-and-go test [time needed to rise from a chair and start walking], the number of falls in the last 6 months).

• Comorbidity.

• Cognition (Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test).

• Psychological state (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale).

• Social functioning (Medical Outcomes Study Social Activity Limitations Measure).

• Social support (Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, Seeman and Berkman Social Ties).

• Nutritional status (body mass index, percentage unintentional weight loss in the last 6 months).

"We really looked at what are the factors – other than chronologic age – that can tell us about this individual," said Dr. Hurria.

Two physicians graded chemotherapy toxicities using the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (v3.0) to determine whether the event was due to disease or chemotherapy. Patients were followed until the end of the regimen.

"We felt that in order for a measure to be utilized in clinical practice, we would need to increase both the ease of administration and the ease of the scoring by having health care providers be able to ask single questions to the patient in order to assess their risk," she said.

Therefore, the researchers developed the scoring algorithm, assigning points to each risk factor, and then used the whole cohort to determine how total score relates to chemotoxicity risk.

The CRASH Score

Developed by Dr. Extermann and her coinvestigators, the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score also evaluates an elderly patient’s risk for grade 4 hematologic and grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicities during chemotherapy.

"This score is helping define – a priori – the level of risk that a patient has for side effects. This way, we know how closely we need to watch the patient during chemotherapy, what strength of chemotherapy we should give, or if we should give chemotherapy at all," said Dr. Extermann.

Investigators enrolled patients from the Moffitt Cancer Center and six community centers. The process included a baseline assessment within 2 weeks of starting chemotherapy and weekly complete blood cell counts. Any published chemotherapy regimen could be used, and clinicians were free to manage care without restriction.

Toxicity was prospectively evaluated using the MAX2 index, previously developed by Dr. Extermann and her coinvestigators. Patients with dementia or planned concomitant radiotherapy were excluded.

A total of 518 patients were included in the analysis. The median age was 76 years. In all, 23 tumor types, and 111 chemotherapy regimens were included. Almost a third of patients (32%) had grade 4 hematologic toxicities, 56% had grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicity, and 68% had a combination. The median time to first toxicity was 22 days. Development of the model was based on two-thirds of the patient population, and validation on the remaining third.

The study followed patients through the course of chemotherapy up to 1 month after the last cycle. If chemotherapy continued beyond 6 months, assessment was ended at 6 months. The primary end point was the first occurrence of a grade 4 hematologic toxicity and/or a grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicity.

The researchers assessed several independent variables, including age, sex, body mass index, diastolic blood pressure, comorbidities (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics [CIRS-G]), CBC count, liver test results, creatinine clearance, albumin level, self-rated health, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) score, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) results, Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) results, cancer stage, marrow invasion, pretreatment with chemotherapy, tumor response, and chemotoxicity (MAX2 index).

Dr. Extermann noted that other research has suggested that grade 4 hematologic toxicities and grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicities have different predictors. And her group found:

• On univariate analysis for predictors of hematologic toxicities, diastolic blood pressure, albumin, lactate dehydrogenase, and IADL were significant (after adjustment for chemotoxicity).

• ECOG Performance Status, hemoglobin, creatinine clearance, albumin, MMSE, self-rated health, MNA, and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics severity index were significant predictors of nonhematologic toxicities.

The researchers then developed a scoring system for predicting hematologic and nonhematologic chemotoxicity. Scores from both subscales are totaled, and patients with a score of 0-3 are considered low risk while those with a score of 4-6 are grouped as intermediate low risk and those with 7-9 are intermediate high risk. Patients with a score greater than 9 are considered high risk.

A Young Field Looks Ahead

Dr. Extermann is planning to extend her scoring tool to include chemoradiation therapy. The score will also need to be validated for specific tumor types, and she would like to assess what happens once a patient has a severe toxicity. What predicts that they are going to have another one? Another question is whether a score can help identify a starting chemotherapy dose.

Dr. Hurria plans to validate her group’s model in a larger group of patients. It also needs to be validated for patients with specific cancers, such as breast or prostate. This could provide an evidence base to identify specific interventions to reduce or prevent severe chemotoxicities. Work also needs to be done on the pharmacology of chemotherapy drugs and how the pharmacology changes with the aging process.

No less important will be gaining insight into the decision making process as more choices become available to the elderly, she added. How can an oncologist understand what’s meaningful to the patient choosing among options? What’s the best way to communicate with this growing patient group?

Dr. Extermann reported that she has received honoraria from Amgen Inc. Dr. Hurria reported that she has significant financial relationships with Amgen, Genentech Inc., Abraxis BioScience Inc., and Pfizer Inc.

The increasing number and efficacy of chemotherapy drugs for a host of cancers – coupled with growth of the older population – not only means that elderly patients have more options for treatment, but also that more of these patients, even among the older old, can be considered candidates for chemotherapy.

This marks a big shift in the way that oncologists approach cancer treatment for patients of advanced age. Until recently, palliative care was the only treatment offered, according to interviews with leaders in geriatric oncology.

"Starting in the mid-1980s, people began to talk about these issues and the need for data and information. Just talking about it began to raise the consciousness that age was not a contraindication per se," said Dr. James S. Goodwin, director of the Sealy Center on Aging at the University of Texas at Galveston.

The numbers are clear: The baby boom is about to turn into a geriatric blast for oncologists. In 2050, the number of Americans aged 65 and older is projected to be 88.5 million, more than double the 40.2 million projected today, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In addition, total cancer incidence is projected to increase by approximately 45%, from 1.6 million this year to 2.3 million in 2030. A 67% increase in cancer incidence is anticipated for older adults (J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:2758-65).

With more people living longer, some say the expansion has already begun. "Oncologists are seeing these patients in everyday practice," observed Dr. Arti Hurria, director of the Cancer and Aging Research Program at City of Hope in Duarte, Calif.

But defining these patients is turning out to be a challenge for geriatric oncologists, and determining the best treatment can be even more difficult.

How Old Is Old?

It’s not clear what "geriatric" means in this context. Intuitively, most people have a mental picture but putting it into words – or finding an agreed-upon age cutoff – is a bit elusive.

"Chronologic age doesn’t equal functional age," said Dr. Hurria An individual can be quite healthy at 80 years with little comorbidity; alternatively a 50-year-old with several health conditions can be quite sick. "In our research studies, we’ve really been forced to have to think about some sort of chronologic cutoff."

Age 65 has frequently been used because historically it’s a time when people retire and become eligible for benefits in the United States, she explained. But many facets of aging appear after age 70, and using data from a study of 500 cancer patients at least 65 years of age, Dr. Hurria and her colleagues found age 73 to be a good cutoff.

"In some ways, that was very reassuring because it really added evidence to our feeling that the seventh decade of life is a time when people become more vulnerable," she said. "It also happens to be a group – age 73 or 75 and older – that has been very underrepresented in clinical trials."

That’s not to say that everyone in their mid-70s or older is feeble and in poor health. Instead, it signals the need for further evaluation of an individual’s physiologic status. "From an epidemiologic point of view, what happens in the 70s is that a lot of people start developing health problems," said Dr. Martine Extermann, who has developed an instrument for evaluation of these patients and is professor of oncology at the University of South Florida and attending physician at Moffitt Cancer Center, in Tampa.

For Dr. Goodwin, the cutoff can be even higher. "People live 10 years longer today on average than when I graduated from medical school," said Dr. Goodwin. "So whatever idea we have about what an old person is, needs to be shifted up by 10 years."

In conversations about geriatric oncology with oncologists, he tends to start at age 80. "If you say 80 and older, you can let age be the factor," he explained. "Age is a very strong predictor of health and mortality. You can’t make that go away by factoring in all of the measurements that you might make about how well they function or how fast they walk."

Dr. Hurria said she likens geriatric oncology to pediatric oncology, a specialty that is also defined by age. The term geriatric oncology "highlights that there is a segment of the population that is potentially vulnerable because of things other than chronologic age. ... We also need to develop an evidence base."

"The definition of geriatric oncology is that we have a population, in which we need to do additional screening and evaluation in order to give the proper treatment," agreed Dr. Extermann, professor of oncology and internal medicine at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa.

Who Needs an In-Depth Assessment?

If not all older patients are especially vulnerable, the challenge becomes determining which patients need extra attention. The following two-tiered approach to the evaluation and management of geriatric oncology patients would divide the elderly into two groups (Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005;55:241-52):

• The first step would be to screen all older patients for vulnerability to stressors – such as chemotherapy. This should include the assessment of nutritional status, performance status, psychological state (depression), cognition, daily activity, and comorbidities. Those who are considered fit would be managed like younger patients.

• Next, frailer patients would undergo a more thorough evaluation – a comprehensive geriatric assessment – so that an optimal treatment plan could be created. The in-depth evaluation would look at an elderly person’s functional ability, physical health, cognitive and mental health, and socioenvironmental situation.

With the two-tier evaluation, "the idea is that we need a more integrated approach that is going to include a good geriatric evaluation," said Dr. Extermann, a member of the task force that proposed the approach. The ultimate goal is to match the treatment to the patient and the cancer.

In a large academic setting, a multidisciplinary team can do a more in-depth screening if necessary, she added. For private practice oncologists, the initial evaluation may indicate which patients should be referred for special care.

Where Are the Clinical Trial Data?

Another hurdle in geriatric oncology is the need for more clinical trial data that include this patient population. It’s estimated by the National Cancer Institute that more than 60% of new cancer cases occur among the elderly, but they account for about a quarter of the patients enrolled in randomized clinical trials.

"As the population is aging and most of our patients are older adults, what we’re realizing is that the inclusion criteria for those trials [in the past] did not necessarily reflect the patient who’s sitting in front of us in daily practice," Dr. Hurria said.

Although there are exceptions (notably, recent trials assessing a carboplatin-paclitaxel regimen for non–small-cell lung cancer and the VISTA [Velcade as Initial Standard Therapy for Multiple Myeloma] regimen), the lack of data on the efficacy and safety of chemotherapy regimens in the elderly has left most oncologists to rely on their own judgment.

"There is a need to develop trials for patients who might not be fit enough to participate in standard clinical trials. We still realize that there is an evidence base that we need for those patients," she said.

Research in geriatric oncology has become a priority for several organizations, among them the Geriatric Oncology Consortium and the International Society of Geriatric Oncology.

Chemotoxicity Risk

A prominent area of geriatric oncology research is the assessment of chemotoxicity in an older patient population. Dr. Extermann and Dr. Hurria each presented data at this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology on the development of risk models/scores to assess an older patient’s risk of developing chemotoxicity.

Despite her experience in geriatric oncology, Dr. Extermann was surprised to find that sometimes her opinion of a patient could be widely divergent from that of the scoring tool she developed. In other cases, "when I was sitting on the fence about whether or not to treat a patient, the score helped me decide," she said.

"It’s also very important to realize that having one such toxicity does not necessarily make the patient sick," she noted. Usually toxicities lead to some modification of the treatment. So while greater risk of chemotoxicities may look foreboding, patients are often able to tolerate the regimen with modification and can function with some help.

It’s not just a question of tolerating classic chemotoxicities, however. "If they’re already having trouble getting around their apartment and they fell once a year ago ... any kind of assault on the body may lead to a decompensation," said Dr. Goodwin.

The CARG Chemotoxicity Risk Score

Dr. Hurria and her coinvestigators followed 500 cancer patients 65 years and older throughout chemotherapy to find factors predictive of chemotoxicity, and used their findings to develop the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) Chemotoxicity Risk Score.

Age, cancer type, chemotherapy dose, number of chemotherapy drugs, anemia, and low creatinine clearance were among 11 key factors identified by the study. The rest were based on the answers to five key questions assessing various geriatric measures: self-rated hearing, number of falls in the last 6 months, need for help in taking medications, ability to walk one block, and level of social activities.

Dr. Hurria reported a significant association between the patients’ baseline risk scores and their subsequent risk of grade 3-5 chemotherapy toxicity. Those with a score greater than 12 had an 83% overall risk of grade 3-5 toxicity,compared with 27% for those with a score of 0-5. The investigators divided the study population into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk categories based on the scores.

Cancer patients 65 years and older were eligible for the study, if they were going to start a new chemotherapy regimen. Geriatric assessment began prior to the start of treatment.

Mean patient age was 73 years, 85% were white, and 56% were women. Nearly two-thirds had stage IV disease, and 70% were on polychemotherapy. In all, 53% had grade 3-5 toxicities due to chemotherapy – of these, 26% had hematologic and 43% had nonhematologic toxicities. The majority of toxicities were grade 3

The study captured laboratory values, documented the chemotherapy the patient underwent – the number of drugs, normal or modified dosing, first-line therapy or other – and asked a host of questions in a geriatric assessment that included:

• Functional status (Activities of Daily Living, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living [IADL], Karnofsky Performance Rating Scale, timed up-and-go test [time needed to rise from a chair and start walking], the number of falls in the last 6 months).

• Comorbidity.

• Cognition (Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test).

• Psychological state (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale).

• Social functioning (Medical Outcomes Study Social Activity Limitations Measure).

• Social support (Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, Seeman and Berkman Social Ties).

• Nutritional status (body mass index, percentage unintentional weight loss in the last 6 months).

"We really looked at what are the factors – other than chronologic age – that can tell us about this individual," said Dr. Hurria.

Two physicians graded chemotherapy toxicities using the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (v3.0) to determine whether the event was due to disease or chemotherapy. Patients were followed until the end of the regimen.

"We felt that in order for a measure to be utilized in clinical practice, we would need to increase both the ease of administration and the ease of the scoring by having health care providers be able to ask single questions to the patient in order to assess their risk," she said.

Therefore, the researchers developed the scoring algorithm, assigning points to each risk factor, and then used the whole cohort to determine how total score relates to chemotoxicity risk.

The CRASH Score

Developed by Dr. Extermann and her coinvestigators, the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score also evaluates an elderly patient’s risk for grade 4 hematologic and grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicities during chemotherapy.

"This score is helping define – a priori – the level of risk that a patient has for side effects. This way, we know how closely we need to watch the patient during chemotherapy, what strength of chemotherapy we should give, or if we should give chemotherapy at all," said Dr. Extermann.

Investigators enrolled patients from the Moffitt Cancer Center and six community centers. The process included a baseline assessment within 2 weeks of starting chemotherapy and weekly complete blood cell counts. Any published chemotherapy regimen could be used, and clinicians were free to manage care without restriction.

Toxicity was prospectively evaluated using the MAX2 index, previously developed by Dr. Extermann and her coinvestigators. Patients with dementia or planned concomitant radiotherapy were excluded.

A total of 518 patients were included in the analysis. The median age was 76 years. In all, 23 tumor types, and 111 chemotherapy regimens were included. Almost a third of patients (32%) had grade 4 hematologic toxicities, 56% had grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicity, and 68% had a combination. The median time to first toxicity was 22 days. Development of the model was based on two-thirds of the patient population, and validation on the remaining third.

The study followed patients through the course of chemotherapy up to 1 month after the last cycle. If chemotherapy continued beyond 6 months, assessment was ended at 6 months. The primary end point was the first occurrence of a grade 4 hematologic toxicity and/or a grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicity.

The researchers assessed several independent variables, including age, sex, body mass index, diastolic blood pressure, comorbidities (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics [CIRS-G]), CBC count, liver test results, creatinine clearance, albumin level, self-rated health, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) score, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) results, Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) results, cancer stage, marrow invasion, pretreatment with chemotherapy, tumor response, and chemotoxicity (MAX2 index).

Dr. Extermann noted that other research has suggested that grade 4 hematologic toxicities and grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicities have different predictors. And her group found:

• On univariate analysis for predictors of hematologic toxicities, diastolic blood pressure, albumin, lactate dehydrogenase, and IADL were significant (after adjustment for chemotoxicity).

• ECOG Performance Status, hemoglobin, creatinine clearance, albumin, MMSE, self-rated health, MNA, and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics severity index were significant predictors of nonhematologic toxicities.

The researchers then developed a scoring system for predicting hematologic and nonhematologic chemotoxicity. Scores from both subscales are totaled, and patients with a score of 0-3 are considered low risk while those with a score of 4-6 are grouped as intermediate low risk and those with 7-9 are intermediate high risk. Patients with a score greater than 9 are considered high risk.

A Young Field Looks Ahead

Dr. Extermann is planning to extend her scoring tool to include chemoradiation therapy. The score will also need to be validated for specific tumor types, and she would like to assess what happens once a patient has a severe toxicity. What predicts that they are going to have another one? Another question is whether a score can help identify a starting chemotherapy dose.

Dr. Hurria plans to validate her group’s model in a larger group of patients. It also needs to be validated for patients with specific cancers, such as breast or prostate. This could provide an evidence base to identify specific interventions to reduce or prevent severe chemotoxicities. Work also needs to be done on the pharmacology of chemotherapy drugs and how the pharmacology changes with the aging process.

No less important will be gaining insight into the decision making process as more choices become available to the elderly, she added. How can an oncologist understand what’s meaningful to the patient choosing among options? What’s the best way to communicate with this growing patient group?

Dr. Extermann reported that she has received honoraria from Amgen Inc. Dr. Hurria reported that she has significant financial relationships with Amgen, Genentech Inc., Abraxis BioScience Inc., and Pfizer Inc.