User login

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

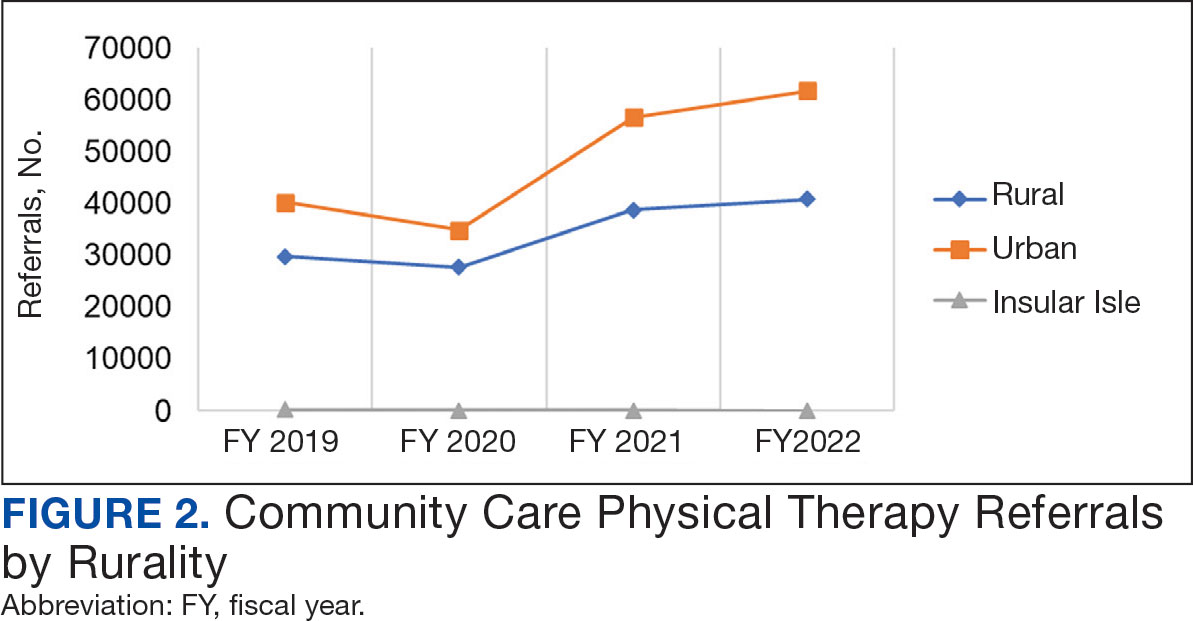

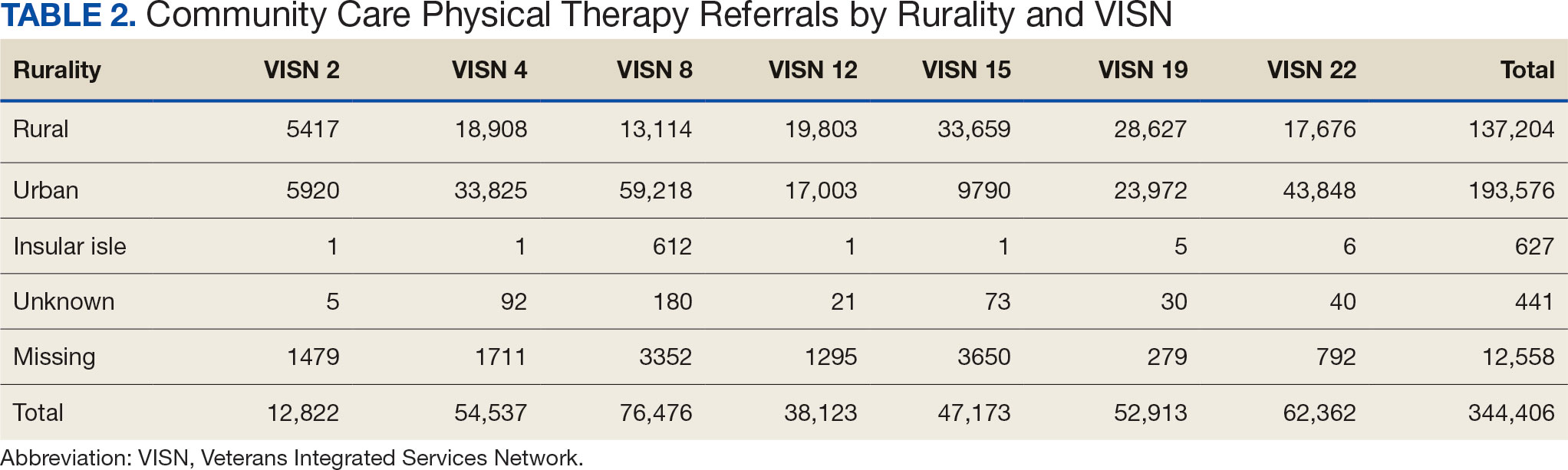

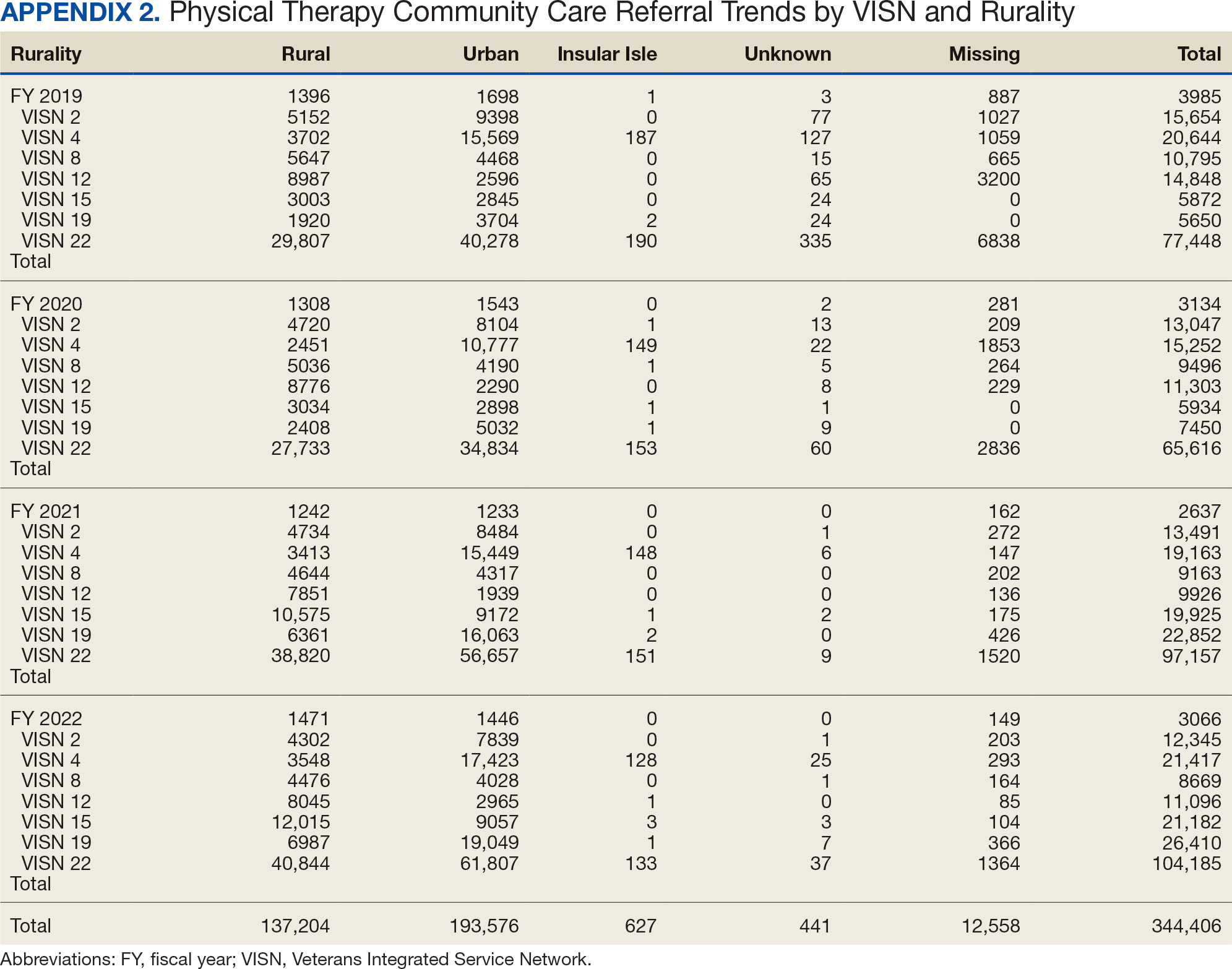

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

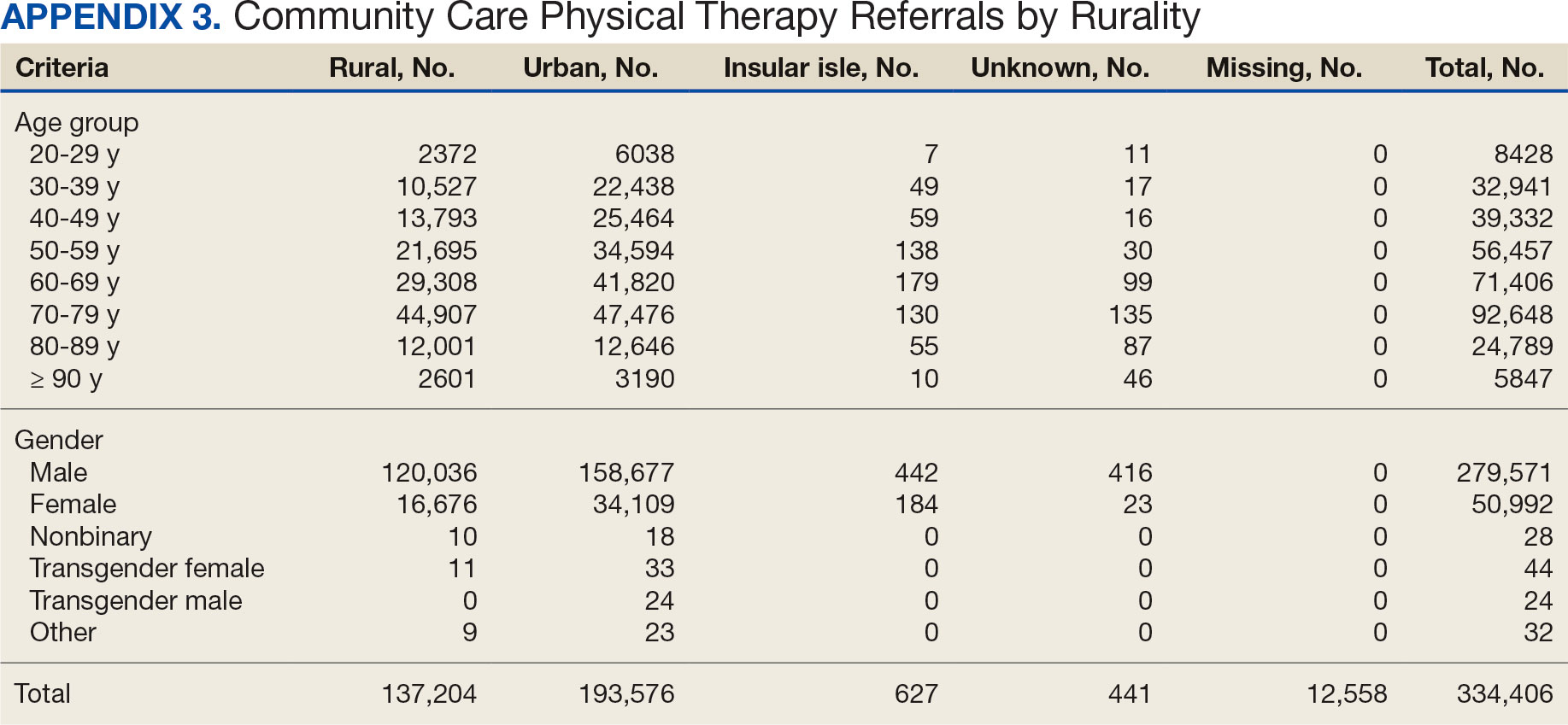

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health care system, providing health care to > 9 million veterans annually. Dementia affects > 7.2 million Americans, and an estimated 450,000 veterans live with Alzheimer disease (AD).1,2 Compared with the general population, veterans have a higher burden of chronic medical conditions and are disproportionately affected by AD due to exposure to military-related risk factors (eg, traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder) and the high prevalence of nonmilitary risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease. The VHA is a pioneer in dementia care, having established a Dementia System of Care to provide primary and specialty care to veterans with dementia. The VHA also is leading the way in implementing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) framework for providing goal-concordant care in > 100 VHA medical centers. The VHA aims to be the largest AFHS in the country.

AD profoundly affects individuals and their families. The progressive nature of the most common form of dementia diminishes the quality of life for patients as well as their care partners in an ongoing fashion, often leading to emotional, physical, and financial strain. Costs for health and long-term care for people living with AD and other dementias were projected at $360 billion in 2024, largely due to the need for nursing home care.1 Although several oral medications are available, their capacity to effectively mitigate the negative effects of AD is limited. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may offer temporary symptomatic relief, but they do not alter disease progression.3 The use of these agents is relatively low, with about one-third of patients diagnosed with AD receiving these medications.4

Amyloid-Targeting Therapies

Recent advancements in biologics, particularly amyloid-targeting therapies, such as lecanemab and donanemab, offer new hope for managing AD. Older adults treated with these medications show less decline on measures of cognition and function than those receiving a placebo at 18 months.5,6 However, accessing and using these medications is challenging.

Use of amyloid-targeting therapies poses challenges. The medications are expensive, potentially placing a financial burden on patients, families, and health care systems.7 Determining initial eligibility for treatment requires a battery of cognitive assessments, laboratory tests, advanced radiologic studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the brain and amyloid positron emission tomography [PET] scans), and possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Frequent ongoing assessments are necessary to monitor safety and efficacy. These treatments carry substantial risks, particularly amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) such as cerebral edema, microhemorrhages, and superficial siderosis. Therefore, follow-up assessments typically occur around months 2, 3, 4, and 7, depending on which medication is selected. Finally, at present, both agents must be intravenous (IV)-administered in a monitored clinical setting, which requires additional coordination, transportation, and cost.

Ongoing evaluations and in-person administration particularly affect patients and care partners with limitations regarding transportation, time off work, and navigating complex health care systems.8 VHA clinicians at sites that have implemented or are interested in implementing amyloid-targeting therapy programs endorse similar challenges when implementing these therapies in their US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs).9

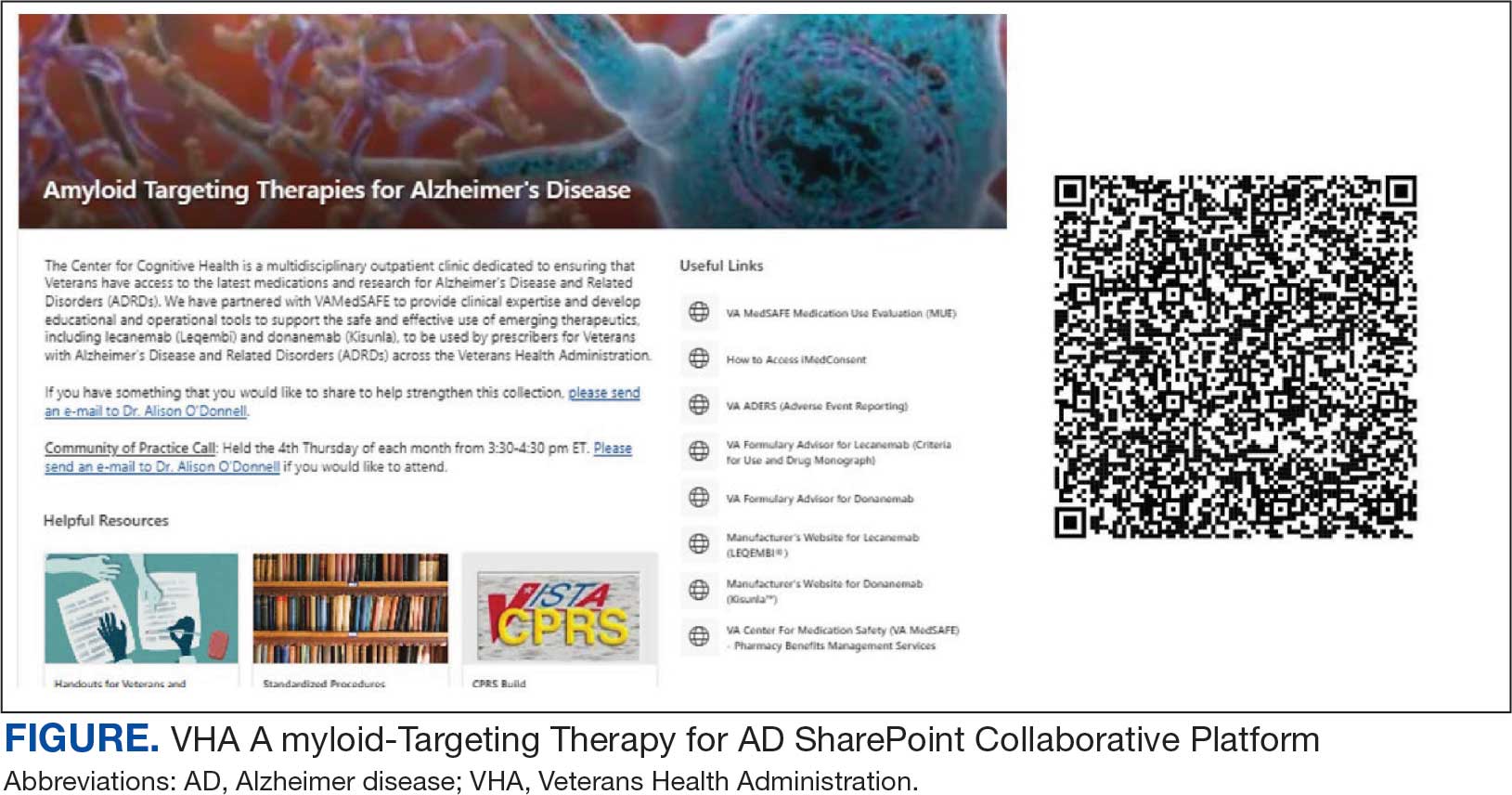

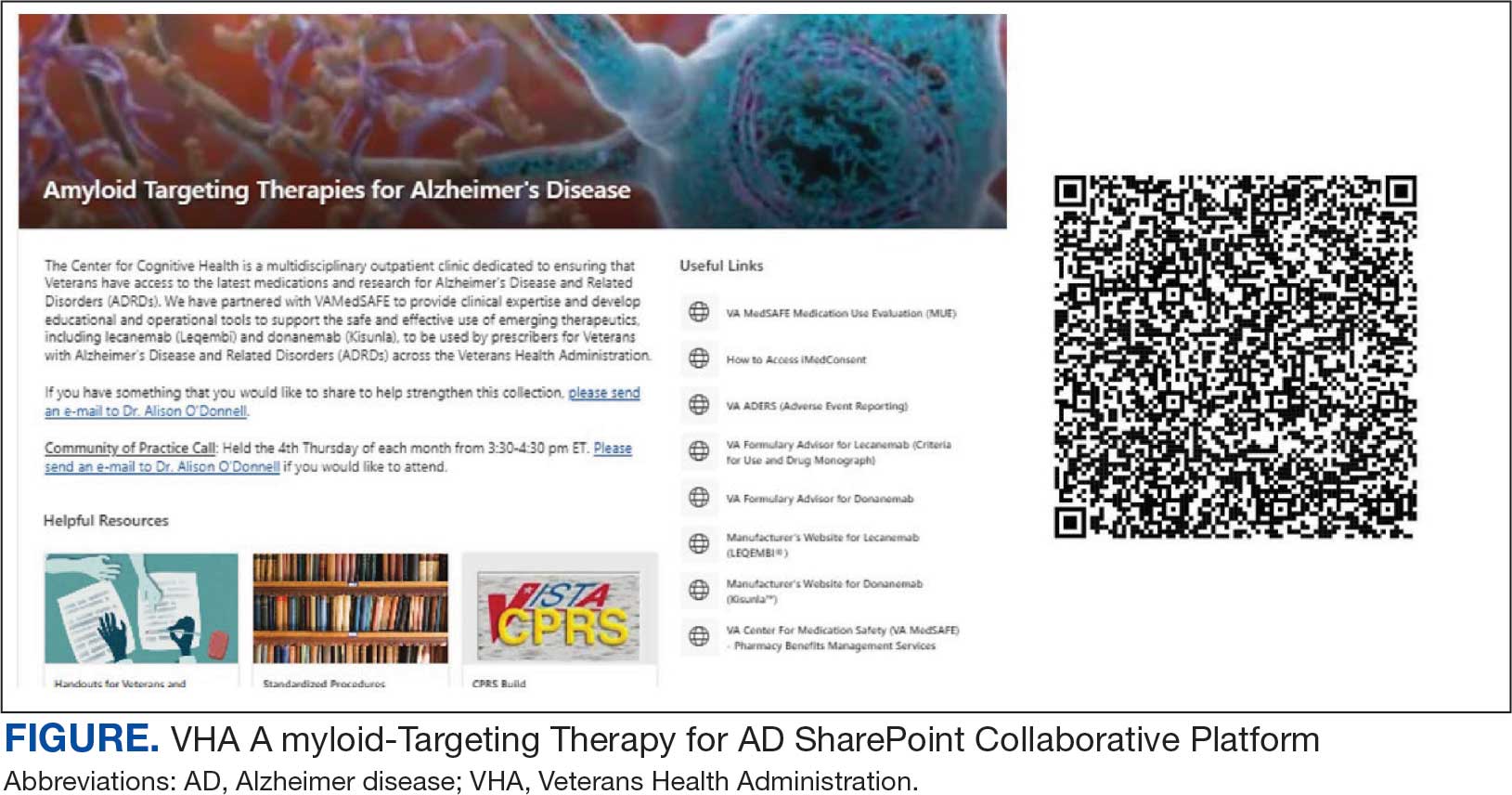

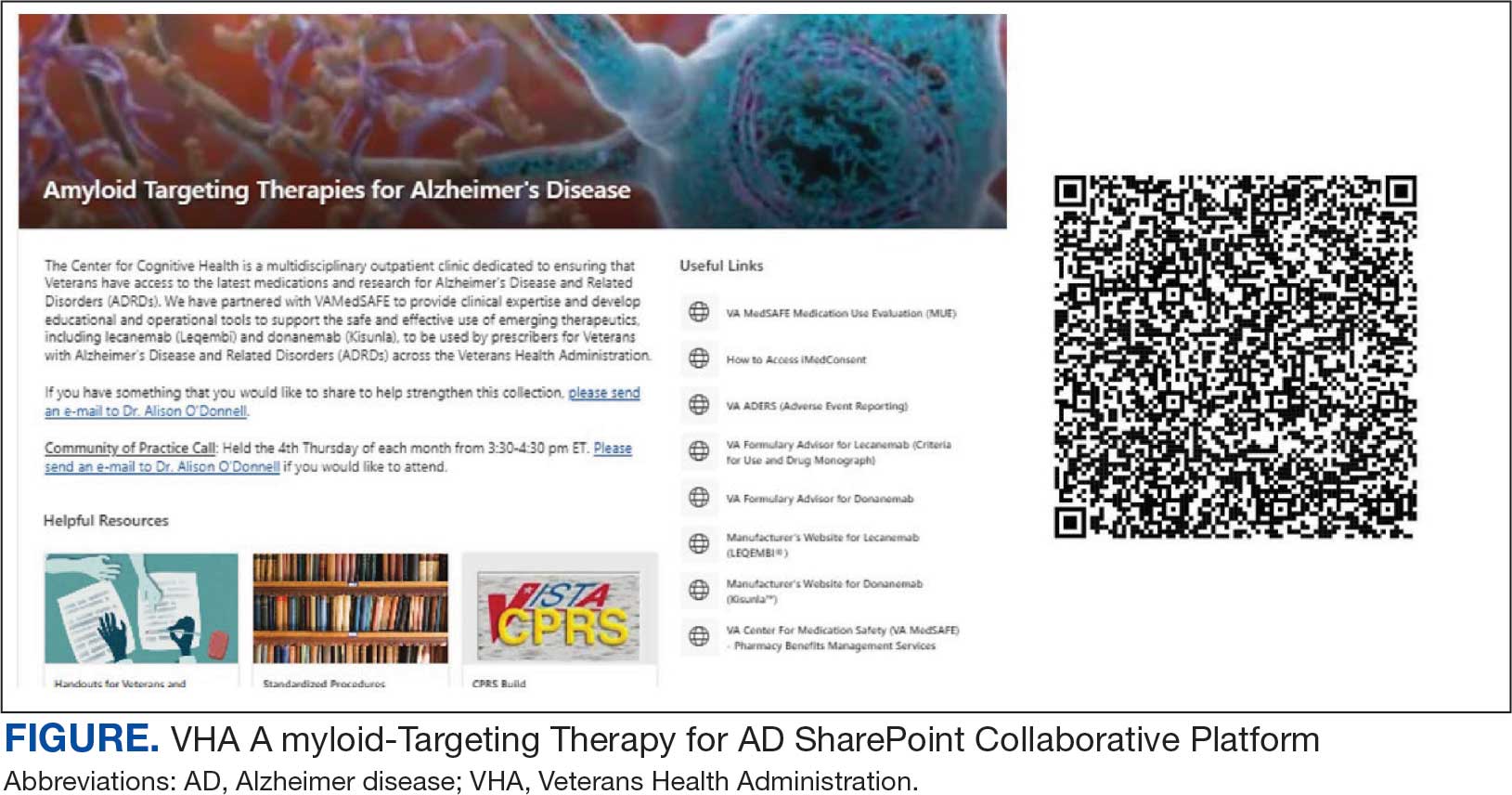

The VHA was one of the first health care systems to use amyloid-targeting therapies, covering the cost of lecanemab and donanemab, in addition to costs associated with concomitant evaluation and testing. However, given the safety concerns with this novel class of medications, the VHA National Formulary Committee developed criteria for use and recommended the VA Center for Medication Safety (VAMedSAFE) conduct a mandatory real-time medication use evaluation (MUE). VAMedSAFE developed the MUE to monitor the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapy for AD. Two authors (AJO, SMH) partnered with VAMedSAFE through the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Technology Enhancing Cognition and Health–Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (TECH-GRECC) to provide clinical expertise, substantive feedback for the development of the MUE, and guidance for VHA sites starting amyloid targeting-therapy programs. We started a VHA Amyloid-Targeting Therapy for AD SharePoint collaborative platform and VHA AD Therapeutics Community of Practice (CoP) for shared learning (Figure). The private SharePoint platform houses an array of implementation materials for VAMCs starting programs: key documents and links; educational materials; sample guidelines; note templates; and electronic health record screenshots. The CoP allows VHAs to share best practices and discuss challenges.

Even with these advantages, we found that ensuring the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapies did not overcome the barriers associated with their complexity. This was especially true for veterans living in rural areas. Only 4 VAMCs had administered amyloid-targeting therapies in the first year they were available. Preliminary data demonstrated that 27 (84%) of 32 veterans who initiated lecanemab in the VHA between October 2023 and September 2024 resided in urban areas.10 To address the underutilization of amyloid-targeting therapy, we propose leveraging the strengths of VHA telehealth to facilitate expansion of access to these medications for veterans with early AD. Telehealth may substantially increase access to evaluation for veterans with early dementia and, when medically appropriate, to receive amyloid-targeting therapies by reducing transportation needs and mitigating costs while ensuring appropriate monitoring through ongoing clinical assessments.

Using Telehealth

The VHA is a pioneer in telehealth, with programs dating back to 2003.11 Between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, the VHA served > 900,000 veterans through the provision of > 2.6 million episodes of care via telehealth.12 The COVID-19 pandemic further cemented the role of telemedicine as an essential component of health care. Telehealth has demonstrated success in the assessment and management of individuals living with dementia. At the VHA, the GRECC-Connect Project is a partnership between 9 urban GRECC sites that seek to provide consultative geriatric and dementia care to rural veterans through telehealth.13 Additional evidence supports the potential to leverage telehealth to effectively communicate results of amyloid PET scans.14

This approach is not without limitations such as the digital divide, or the gap that separates technology-enabled individuals and those unprepared to adopt technology due to limited digital literacy levels or access to needed hardware, software, and connectivity. The VHA has taken steps to address these digital divide barriers by broadly providing tools—such as tablets and broadband connectivity—to veterans. Specifically, the VHA has instituted digital divide consults to determine whether telehealth could be a potential solution for appropriate veterans and to provide an iPad (if eligible) to connect with VA clinicians. Complementary to the digital divide consult, a VHA-specific telehealth preparedness assessment tool is under development and being tested by 2 authors (JF, SMH). This telehealth preparedness assessment tool is designed to aid in the seamless integration of telehealth services with the support of tailored education materials specific to gaps in digital literacy that a veteran might experience.

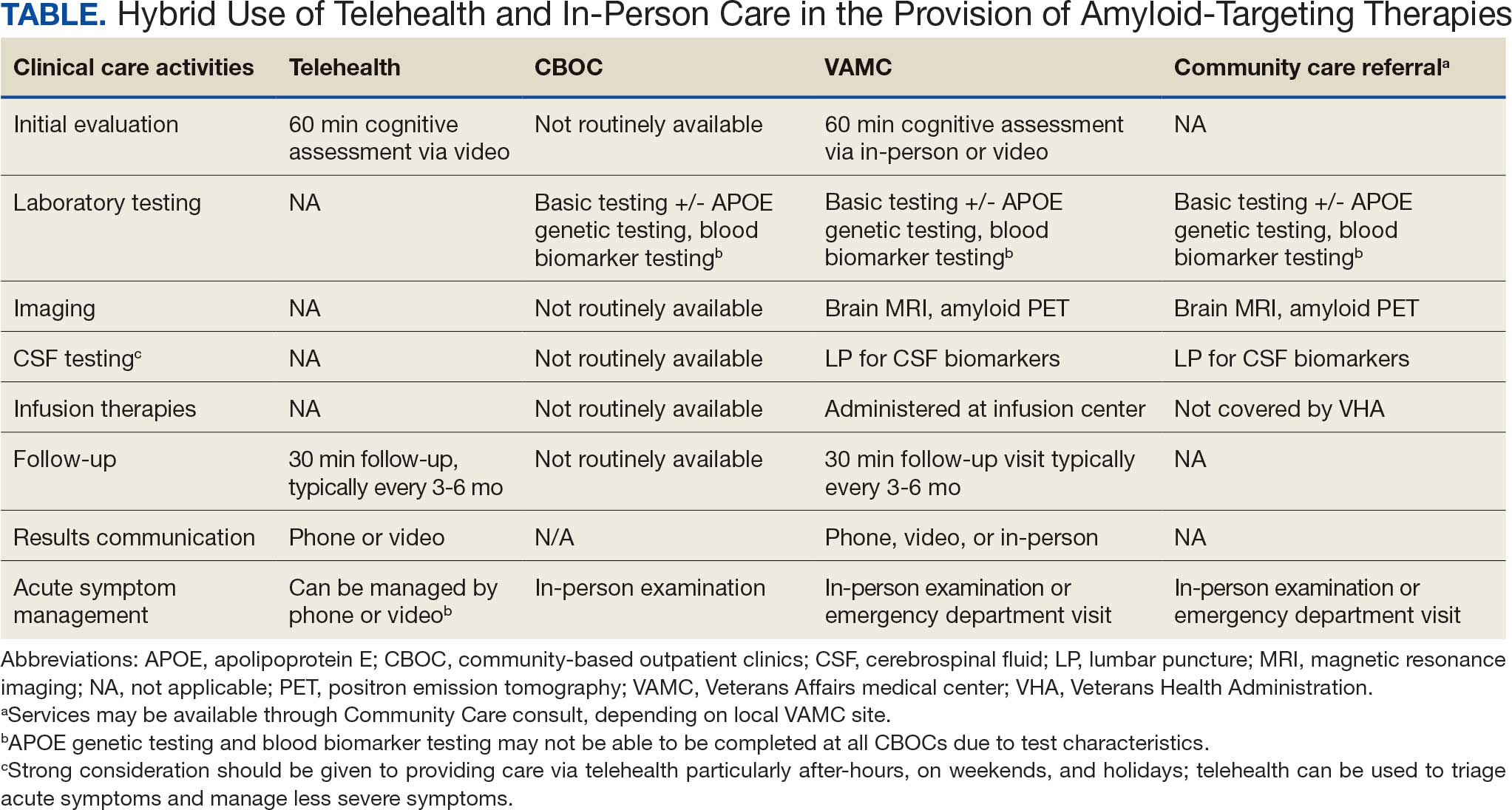

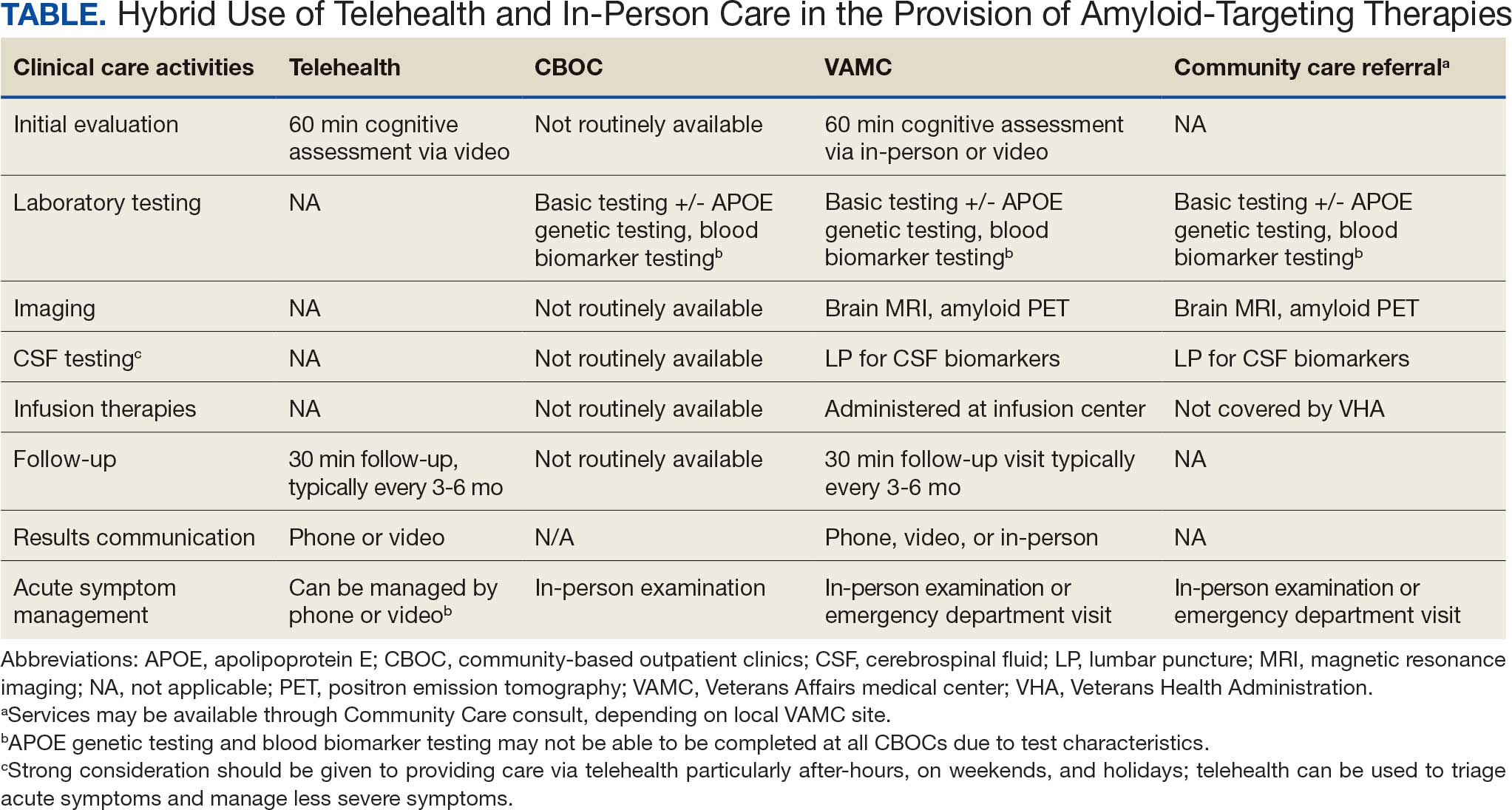

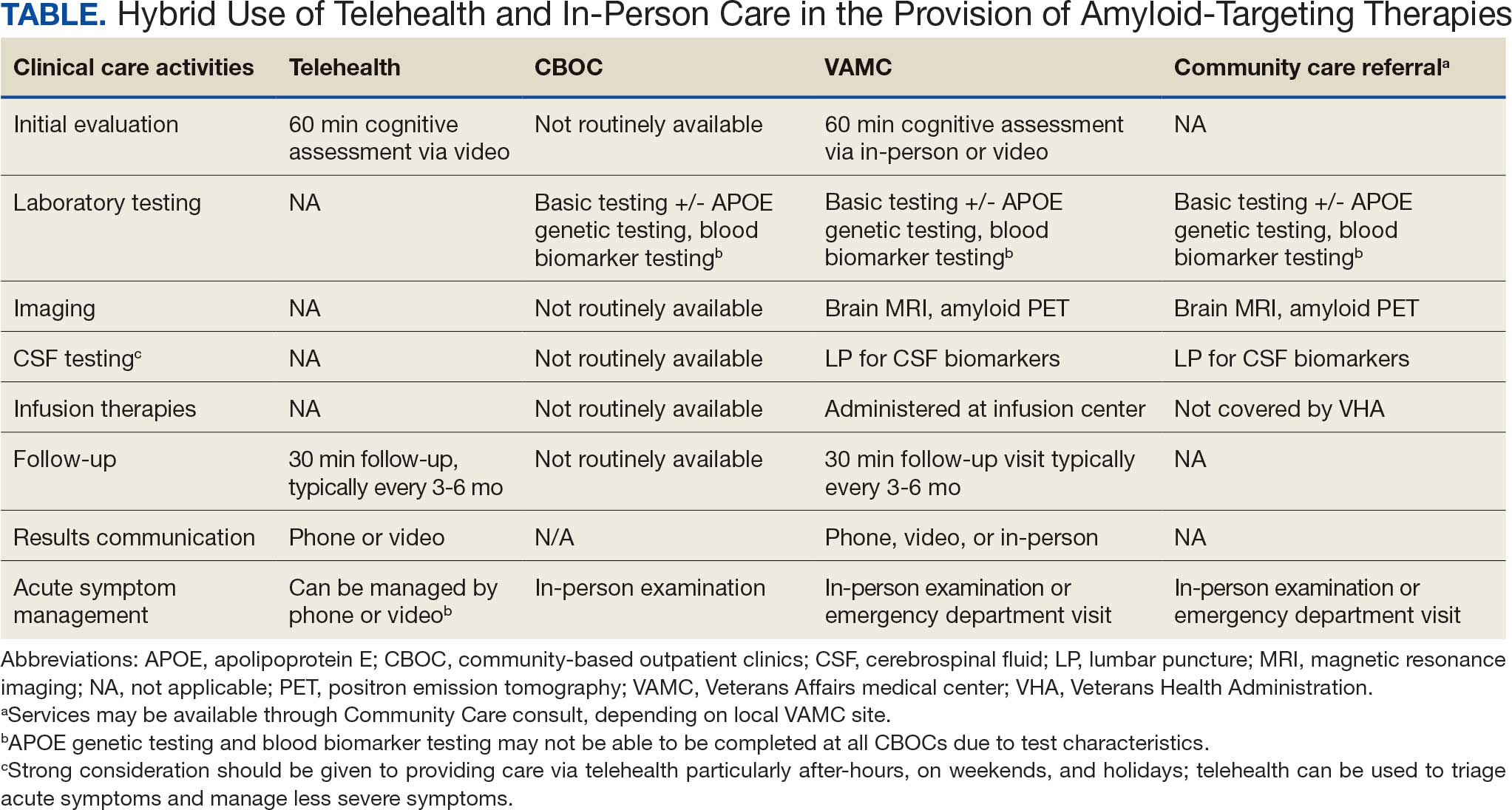

Building on these initiatives, there is an opportunity to expand access to amyloid-targeting therapies, regardless of distance to large VAMCs, by leveraging telehealth as an alternative method of connecting patients with specialty care. Specifically, a hybrid approach could be used to accomplish the myriad initial and follow-up tasks involved in the provision of amyloid-targeting therapies (Table). Not all VHA facilities possess the specialty expertise to prescribe these medications, and local clinicians may not have sufficient knowledge and clinical support to prescribe and monitor these therapies.

The first step is identifying local and regional subject matter experts, followed by the development and expansion of these networks. The National TeleNeurology Program is a good example of a national telehealth program that leverages technology to bring specialty services to rural areas with limited access to care. Although amyloid-targeting therapies often require more complex logistics, such as laboratory tests and imaging, these initial hurdles can be overcome through localized services and collaboration between VAMCs.

While treatment and imaging will most likely need to occur at a VAMC, most basic laboratory studies can be performed at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Some CBOCs may not be able to process more specialized laboratory tests such as apolipoprotein E genetic testing. Samples for these tests can be collected and processed at VAMCs, which usually have contracts with outside laboratories capable of performing these studies. Most, although not all, VAMCs offer advanced imaging, including MRI of the brain and amyloid PETs. VAMCs without those modalities may need to coordinate with other regional VAMCs. Additionally, a pilot program is already underway whereby VAMCs without the ability to quantify the amount of amyloid on PETs are able to leverage technology and collaborations with other VAMCs to obtain these data.

Once the initial phases of evaluation and care are completed, telemedicine can be leveraged for follow-up and ongoing management. Interdisciplinary teams can help facilitate care related to amyloid-targeting therapies, including the close monitoring of veterans for development of ARIA.15 To achieve this monitoring, specialty clinic teams prescribing amyloid-targeting therapies, which may be geographically distant, need to coordinate with local primary care clinical teams and emergency clinicians. All of these health care team members, along with neurologists and neurosurgeons, should be involved in the development and implementation of protocols in the event that patients present to their local primary or specialty care clinics or emergency department with ARIA symptoms.

If amyloid-targeting therapies are to be provided along with other emerging treatments for rural veterans, telehealth must be part of the solution. There is a pressing need to explore innovative evaluation and delivery models for these therapies, particularly as we expect additional diagnostics and therapeutics to be available in the future. With the advent of commercially available blood tests (ie, blood biomarkers) for AD, there is hope for a transition away from PETs and CSF testing given their cost, limited access, and invasiveness for diagnosis and monitoring of AD. These advances will increase the utility of telehealth to help rural veterans access amyloid-targeting therapies.

Additionally, administering the drug at home or at local clinics, supported by a dedicated health care team or home health agency, could further improve accessibility. Telehealth can be leveraged in this scenario, allowing specialty clinics and specialists to connect with patients and clinicians based out of local clinics or even home health agencies. In this scenario, specialists can provide hands-on care guidance and oversight even though they may be geographically distant from care recipients. Transitioning from IV administration to subcutaneous formulations would further enhance convenience and reduce barriers; these formulations may be available soon.16 Addressing logistical challenges to care and access through technology-based solutions will require coordinated efforts and continued VHA investment.

Conclusions

The VHA has a large population of veterans with dementia, and the costs to care for these veterans will only increase. While the current benefits of amyloid-targeting therapies are modest, now is the time to establish care processes that will support future innovations in amyloid-targeting therapies and other treatments and diagnostics. We are developing better ways to detect AD using clinical decision support tools, improving care pathways and the management of AD, and leveraging telehealth to improve access. The VA is conducting research to investigate whether a cognitive screening and laboratory evaluation that includes a telehealth preparedness assessment will be feasible and effective for improving the detection of AD and access to treatment, and we plan to publish the results.

The lessons learned can be extended to non-VHA care settings to help achieve potential benefits for other patients with early AD. Emerging therapies have the potential to improve the quality of life for both patients and care partners, adding life to years and not just years to life. Policymakers and payors must prioritize research funding to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches to the delivery of health services, ensuring that emerging therapies are accessible for all individuals affected by AD.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(4):e70235. doi:10.1002/alz.70235

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Statistical Projections of Alzheimer’s Dementia for VA Patients, VA Enrollees, and US Veterans. December 18, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_ALZHEIMERS_DEMENTIA_Statistical_Projections_FY21_and_FY33_sgc121820.pdf

- Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J. Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: are they effective? P T. 2010;35(4):208-211.

- Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, et al. Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):579-589. doi:10.3233/JAD-200133

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

- Tanne JH. Lecanemab: US Veterans Health Administration will cover cost of new Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ. 2023;380:p628. doi:10.1136/bmj.p628

- Nadeau SE. Lecanemab questions. Neurology. 2024;102(7):e209320. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209320 9. O’Donnell AJ, Fortunato AT, Spitznogle BL, et al. Implementation of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: facilitators and barriers. Presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago. May 2025.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- Hopp F, Whitten P, Subramanian U, et al. Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration about opportunities and barriers in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(8):404-409. doi:10.1258/135763306779378717

- VA reports significant increase in veteran use of telehealth services. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-reports-significant-increase-in-veteran-use-of-telehealth-services/

- Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, et al. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

- Erickson CM, Chin NA, Rosario HL, et al. Feasibility of virtual Alzheimer’s biomarker disclosure: findings from an observational cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9(3):e12413. doi:10.1002/trc2.12413

- Turk KW, Knobel MD, Nothern A, et al. An interprofessional team for disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer disease implementation. Neurol Clin Pract. 2024;14(6):e200346. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200346

- FDA accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) biologics license application for subcutaneous maintenance dosing for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Elsai US. January 13, 2025. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://media-us.eisai.com/2025-01-13-FDA-Accepts-LEQEMBI-R-lecanemab-irmb-Biologics-License-Application-for-Subcutaneous-Maintenance-Dosing-for-the-Treatment-of-Early-Alzheimers-Disease

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health care system, providing health care to > 9 million veterans annually. Dementia affects > 7.2 million Americans, and an estimated 450,000 veterans live with Alzheimer disease (AD).1,2 Compared with the general population, veterans have a higher burden of chronic medical conditions and are disproportionately affected by AD due to exposure to military-related risk factors (eg, traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder) and the high prevalence of nonmilitary risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease. The VHA is a pioneer in dementia care, having established a Dementia System of Care to provide primary and specialty care to veterans with dementia. The VHA also is leading the way in implementing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) framework for providing goal-concordant care in > 100 VHA medical centers. The VHA aims to be the largest AFHS in the country.

AD profoundly affects individuals and their families. The progressive nature of the most common form of dementia diminishes the quality of life for patients as well as their care partners in an ongoing fashion, often leading to emotional, physical, and financial strain. Costs for health and long-term care for people living with AD and other dementias were projected at $360 billion in 2024, largely due to the need for nursing home care.1 Although several oral medications are available, their capacity to effectively mitigate the negative effects of AD is limited. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may offer temporary symptomatic relief, but they do not alter disease progression.3 The use of these agents is relatively low, with about one-third of patients diagnosed with AD receiving these medications.4

Amyloid-Targeting Therapies

Recent advancements in biologics, particularly amyloid-targeting therapies, such as lecanemab and donanemab, offer new hope for managing AD. Older adults treated with these medications show less decline on measures of cognition and function than those receiving a placebo at 18 months.5,6 However, accessing and using these medications is challenging.

Use of amyloid-targeting therapies poses challenges. The medications are expensive, potentially placing a financial burden on patients, families, and health care systems.7 Determining initial eligibility for treatment requires a battery of cognitive assessments, laboratory tests, advanced radiologic studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the brain and amyloid positron emission tomography [PET] scans), and possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Frequent ongoing assessments are necessary to monitor safety and efficacy. These treatments carry substantial risks, particularly amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) such as cerebral edema, microhemorrhages, and superficial siderosis. Therefore, follow-up assessments typically occur around months 2, 3, 4, and 7, depending on which medication is selected. Finally, at present, both agents must be intravenous (IV)-administered in a monitored clinical setting, which requires additional coordination, transportation, and cost.

Ongoing evaluations and in-person administration particularly affect patients and care partners with limitations regarding transportation, time off work, and navigating complex health care systems.8 VHA clinicians at sites that have implemented or are interested in implementing amyloid-targeting therapy programs endorse similar challenges when implementing these therapies in their US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs).9

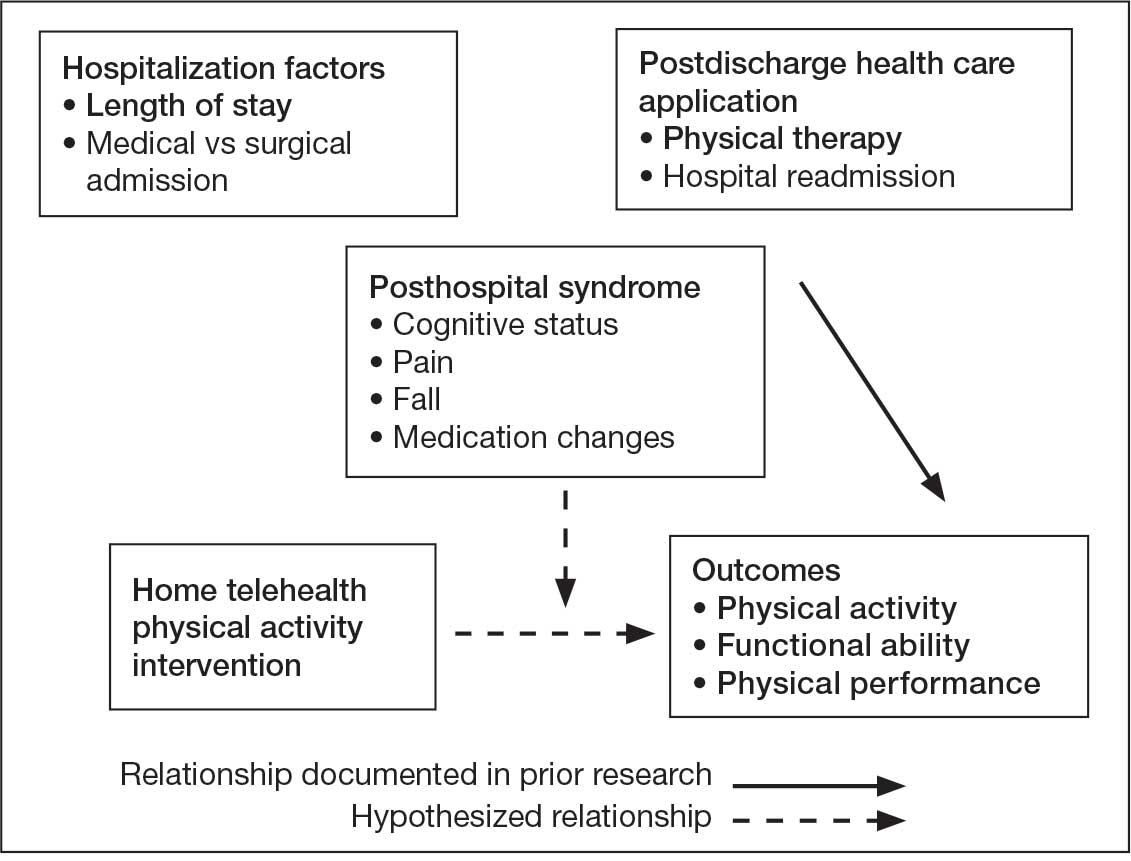

The VHA was one of the first health care systems to use amyloid-targeting therapies, covering the cost of lecanemab and donanemab, in addition to costs associated with concomitant evaluation and testing. However, given the safety concerns with this novel class of medications, the VHA National Formulary Committee developed criteria for use and recommended the VA Center for Medication Safety (VAMedSAFE) conduct a mandatory real-time medication use evaluation (MUE). VAMedSAFE developed the MUE to monitor the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapy for AD. Two authors (AJO, SMH) partnered with VAMedSAFE through the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Technology Enhancing Cognition and Health–Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (TECH-GRECC) to provide clinical expertise, substantive feedback for the development of the MUE, and guidance for VHA sites starting amyloid targeting-therapy programs. We started a VHA Amyloid-Targeting Therapy for AD SharePoint collaborative platform and VHA AD Therapeutics Community of Practice (CoP) for shared learning (Figure). The private SharePoint platform houses an array of implementation materials for VAMCs starting programs: key documents and links; educational materials; sample guidelines; note templates; and electronic health record screenshots. The CoP allows VHAs to share best practices and discuss challenges.

Even with these advantages, we found that ensuring the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapies did not overcome the barriers associated with their complexity. This was especially true for veterans living in rural areas. Only 4 VAMCs had administered amyloid-targeting therapies in the first year they were available. Preliminary data demonstrated that 27 (84%) of 32 veterans who initiated lecanemab in the VHA between October 2023 and September 2024 resided in urban areas.10 To address the underutilization of amyloid-targeting therapy, we propose leveraging the strengths of VHA telehealth to facilitate expansion of access to these medications for veterans with early AD. Telehealth may substantially increase access to evaluation for veterans with early dementia and, when medically appropriate, to receive amyloid-targeting therapies by reducing transportation needs and mitigating costs while ensuring appropriate monitoring through ongoing clinical assessments.

Using Telehealth

The VHA is a pioneer in telehealth, with programs dating back to 2003.11 Between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, the VHA served > 900,000 veterans through the provision of > 2.6 million episodes of care via telehealth.12 The COVID-19 pandemic further cemented the role of telemedicine as an essential component of health care. Telehealth has demonstrated success in the assessment and management of individuals living with dementia. At the VHA, the GRECC-Connect Project is a partnership between 9 urban GRECC sites that seek to provide consultative geriatric and dementia care to rural veterans through telehealth.13 Additional evidence supports the potential to leverage telehealth to effectively communicate results of amyloid PET scans.14

This approach is not without limitations such as the digital divide, or the gap that separates technology-enabled individuals and those unprepared to adopt technology due to limited digital literacy levels or access to needed hardware, software, and connectivity. The VHA has taken steps to address these digital divide barriers by broadly providing tools—such as tablets and broadband connectivity—to veterans. Specifically, the VHA has instituted digital divide consults to determine whether telehealth could be a potential solution for appropriate veterans and to provide an iPad (if eligible) to connect with VA clinicians. Complementary to the digital divide consult, a VHA-specific telehealth preparedness assessment tool is under development and being tested by 2 authors (JF, SMH). This telehealth preparedness assessment tool is designed to aid in the seamless integration of telehealth services with the support of tailored education materials specific to gaps in digital literacy that a veteran might experience.

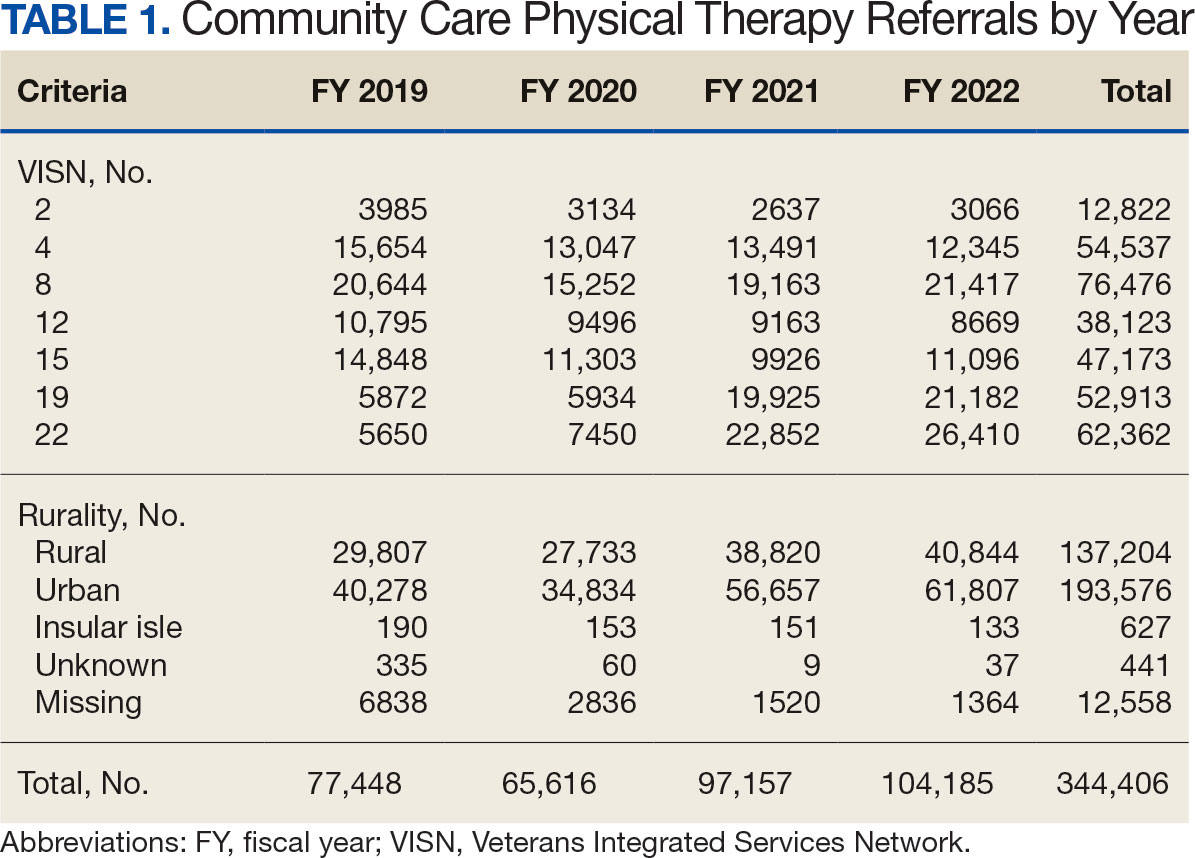

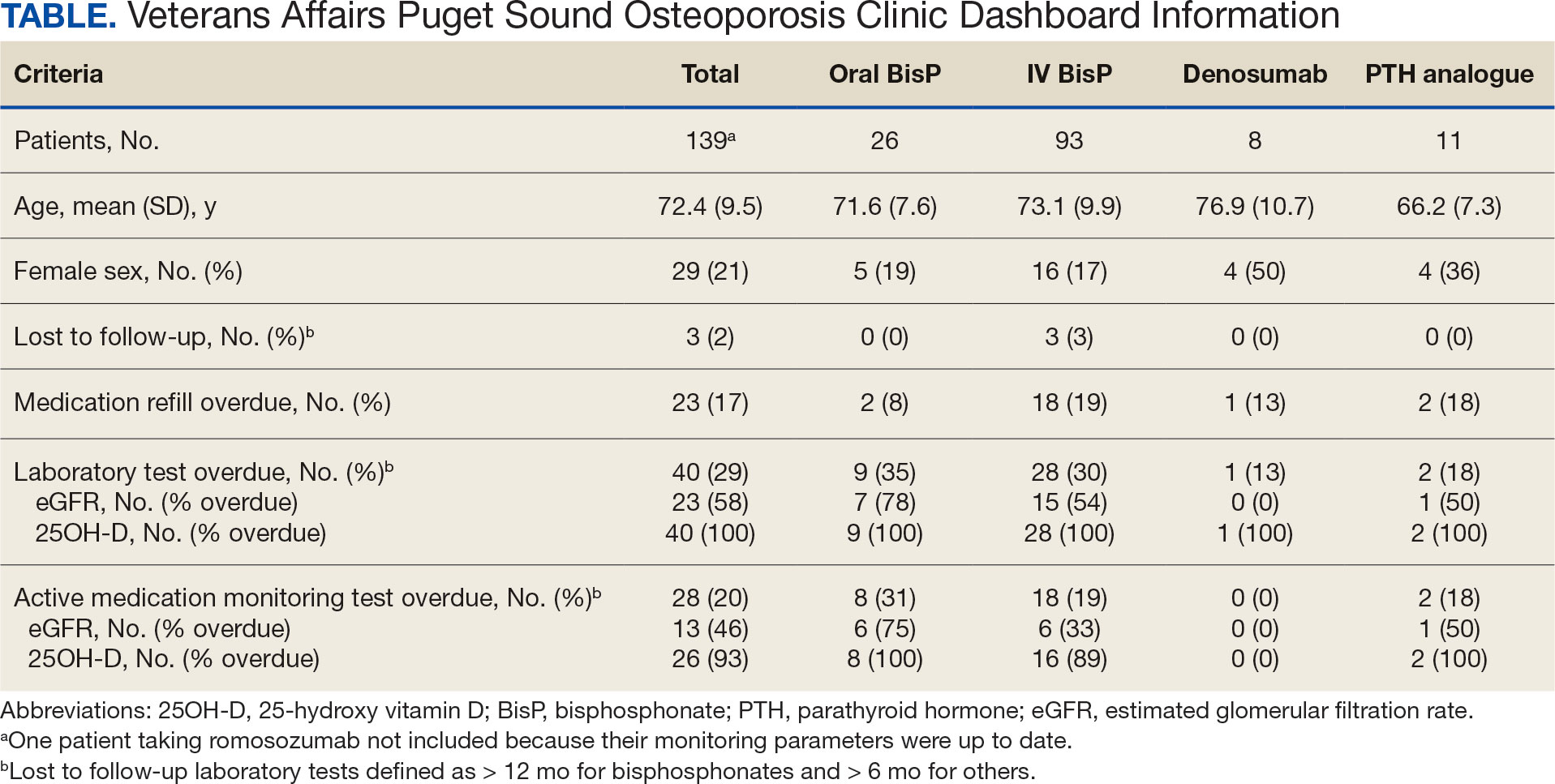

Building on these initiatives, there is an opportunity to expand access to amyloid-targeting therapies, regardless of distance to large VAMCs, by leveraging telehealth as an alternative method of connecting patients with specialty care. Specifically, a hybrid approach could be used to accomplish the myriad initial and follow-up tasks involved in the provision of amyloid-targeting therapies (Table). Not all VHA facilities possess the specialty expertise to prescribe these medications, and local clinicians may not have sufficient knowledge and clinical support to prescribe and monitor these therapies.

The first step is identifying local and regional subject matter experts, followed by the development and expansion of these networks. The National TeleNeurology Program is a good example of a national telehealth program that leverages technology to bring specialty services to rural areas with limited access to care. Although amyloid-targeting therapies often require more complex logistics, such as laboratory tests and imaging, these initial hurdles can be overcome through localized services and collaboration between VAMCs.

While treatment and imaging will most likely need to occur at a VAMC, most basic laboratory studies can be performed at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Some CBOCs may not be able to process more specialized laboratory tests such as apolipoprotein E genetic testing. Samples for these tests can be collected and processed at VAMCs, which usually have contracts with outside laboratories capable of performing these studies. Most, although not all, VAMCs offer advanced imaging, including MRI of the brain and amyloid PETs. VAMCs without those modalities may need to coordinate with other regional VAMCs. Additionally, a pilot program is already underway whereby VAMCs without the ability to quantify the amount of amyloid on PETs are able to leverage technology and collaborations with other VAMCs to obtain these data.

Once the initial phases of evaluation and care are completed, telemedicine can be leveraged for follow-up and ongoing management. Interdisciplinary teams can help facilitate care related to amyloid-targeting therapies, including the close monitoring of veterans for development of ARIA.15 To achieve this monitoring, specialty clinic teams prescribing amyloid-targeting therapies, which may be geographically distant, need to coordinate with local primary care clinical teams and emergency clinicians. All of these health care team members, along with neurologists and neurosurgeons, should be involved in the development and implementation of protocols in the event that patients present to their local primary or specialty care clinics or emergency department with ARIA symptoms.

If amyloid-targeting therapies are to be provided along with other emerging treatments for rural veterans, telehealth must be part of the solution. There is a pressing need to explore innovative evaluation and delivery models for these therapies, particularly as we expect additional diagnostics and therapeutics to be available in the future. With the advent of commercially available blood tests (ie, blood biomarkers) for AD, there is hope for a transition away from PETs and CSF testing given their cost, limited access, and invasiveness for diagnosis and monitoring of AD. These advances will increase the utility of telehealth to help rural veterans access amyloid-targeting therapies.

Additionally, administering the drug at home or at local clinics, supported by a dedicated health care team or home health agency, could further improve accessibility. Telehealth can be leveraged in this scenario, allowing specialty clinics and specialists to connect with patients and clinicians based out of local clinics or even home health agencies. In this scenario, specialists can provide hands-on care guidance and oversight even though they may be geographically distant from care recipients. Transitioning from IV administration to subcutaneous formulations would further enhance convenience and reduce barriers; these formulations may be available soon.16 Addressing logistical challenges to care and access through technology-based solutions will require coordinated efforts and continued VHA investment.

Conclusions

The VHA has a large population of veterans with dementia, and the costs to care for these veterans will only increase. While the current benefits of amyloid-targeting therapies are modest, now is the time to establish care processes that will support future innovations in amyloid-targeting therapies and other treatments and diagnostics. We are developing better ways to detect AD using clinical decision support tools, improving care pathways and the management of AD, and leveraging telehealth to improve access. The VA is conducting research to investigate whether a cognitive screening and laboratory evaluation that includes a telehealth preparedness assessment will be feasible and effective for improving the detection of AD and access to treatment, and we plan to publish the results.

The lessons learned can be extended to non-VHA care settings to help achieve potential benefits for other patients with early AD. Emerging therapies have the potential to improve the quality of life for both patients and care partners, adding life to years and not just years to life. Policymakers and payors must prioritize research funding to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches to the delivery of health services, ensuring that emerging therapies are accessible for all individuals affected by AD.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health care system, providing health care to > 9 million veterans annually. Dementia affects > 7.2 million Americans, and an estimated 450,000 veterans live with Alzheimer disease (AD).1,2 Compared with the general population, veterans have a higher burden of chronic medical conditions and are disproportionately affected by AD due to exposure to military-related risk factors (eg, traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder) and the high prevalence of nonmilitary risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease. The VHA is a pioneer in dementia care, having established a Dementia System of Care to provide primary and specialty care to veterans with dementia. The VHA also is leading the way in implementing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) framework for providing goal-concordant care in > 100 VHA medical centers. The VHA aims to be the largest AFHS in the country.

AD profoundly affects individuals and their families. The progressive nature of the most common form of dementia diminishes the quality of life for patients as well as their care partners in an ongoing fashion, often leading to emotional, physical, and financial strain. Costs for health and long-term care for people living with AD and other dementias were projected at $360 billion in 2024, largely due to the need for nursing home care.1 Although several oral medications are available, their capacity to effectively mitigate the negative effects of AD is limited. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may offer temporary symptomatic relief, but they do not alter disease progression.3 The use of these agents is relatively low, with about one-third of patients diagnosed with AD receiving these medications.4

Amyloid-Targeting Therapies

Recent advancements in biologics, particularly amyloid-targeting therapies, such as lecanemab and donanemab, offer new hope for managing AD. Older adults treated with these medications show less decline on measures of cognition and function than those receiving a placebo at 18 months.5,6 However, accessing and using these medications is challenging.

Use of amyloid-targeting therapies poses challenges. The medications are expensive, potentially placing a financial burden on patients, families, and health care systems.7 Determining initial eligibility for treatment requires a battery of cognitive assessments, laboratory tests, advanced radiologic studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the brain and amyloid positron emission tomography [PET] scans), and possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Frequent ongoing assessments are necessary to monitor safety and efficacy. These treatments carry substantial risks, particularly amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) such as cerebral edema, microhemorrhages, and superficial siderosis. Therefore, follow-up assessments typically occur around months 2, 3, 4, and 7, depending on which medication is selected. Finally, at present, both agents must be intravenous (IV)-administered in a monitored clinical setting, which requires additional coordination, transportation, and cost.

Ongoing evaluations and in-person administration particularly affect patients and care partners with limitations regarding transportation, time off work, and navigating complex health care systems.8 VHA clinicians at sites that have implemented or are interested in implementing amyloid-targeting therapy programs endorse similar challenges when implementing these therapies in their US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs).9

The VHA was one of the first health care systems to use amyloid-targeting therapies, covering the cost of lecanemab and donanemab, in addition to costs associated with concomitant evaluation and testing. However, given the safety concerns with this novel class of medications, the VHA National Formulary Committee developed criteria for use and recommended the VA Center for Medication Safety (VAMedSAFE) conduct a mandatory real-time medication use evaluation (MUE). VAMedSAFE developed the MUE to monitor the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapy for AD. Two authors (AJO, SMH) partnered with VAMedSAFE through the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Technology Enhancing Cognition and Health–Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (TECH-GRECC) to provide clinical expertise, substantive feedback for the development of the MUE, and guidance for VHA sites starting amyloid targeting-therapy programs. We started a VHA Amyloid-Targeting Therapy for AD SharePoint collaborative platform and VHA AD Therapeutics Community of Practice (CoP) for shared learning (Figure). The private SharePoint platform houses an array of implementation materials for VAMCs starting programs: key documents and links; educational materials; sample guidelines; note templates; and electronic health record screenshots. The CoP allows VHAs to share best practices and discuss challenges.

Even with these advantages, we found that ensuring the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapies did not overcome the barriers associated with their complexity. This was especially true for veterans living in rural areas. Only 4 VAMCs had administered amyloid-targeting therapies in the first year they were available. Preliminary data demonstrated that 27 (84%) of 32 veterans who initiated lecanemab in the VHA between October 2023 and September 2024 resided in urban areas.10 To address the underutilization of amyloid-targeting therapy, we propose leveraging the strengths of VHA telehealth to facilitate expansion of access to these medications for veterans with early AD. Telehealth may substantially increase access to evaluation for veterans with early dementia and, when medically appropriate, to receive amyloid-targeting therapies by reducing transportation needs and mitigating costs while ensuring appropriate monitoring through ongoing clinical assessments.

Using Telehealth

The VHA is a pioneer in telehealth, with programs dating back to 2003.11 Between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, the VHA served > 900,000 veterans through the provision of > 2.6 million episodes of care via telehealth.12 The COVID-19 pandemic further cemented the role of telemedicine as an essential component of health care. Telehealth has demonstrated success in the assessment and management of individuals living with dementia. At the VHA, the GRECC-Connect Project is a partnership between 9 urban GRECC sites that seek to provide consultative geriatric and dementia care to rural veterans through telehealth.13 Additional evidence supports the potential to leverage telehealth to effectively communicate results of amyloid PET scans.14

This approach is not without limitations such as the digital divide, or the gap that separates technology-enabled individuals and those unprepared to adopt technology due to limited digital literacy levels or access to needed hardware, software, and connectivity. The VHA has taken steps to address these digital divide barriers by broadly providing tools—such as tablets and broadband connectivity—to veterans. Specifically, the VHA has instituted digital divide consults to determine whether telehealth could be a potential solution for appropriate veterans and to provide an iPad (if eligible) to connect with VA clinicians. Complementary to the digital divide consult, a VHA-specific telehealth preparedness assessment tool is under development and being tested by 2 authors (JF, SMH). This telehealth preparedness assessment tool is designed to aid in the seamless integration of telehealth services with the support of tailored education materials specific to gaps in digital literacy that a veteran might experience.

Building on these initiatives, there is an opportunity to expand access to amyloid-targeting therapies, regardless of distance to large VAMCs, by leveraging telehealth as an alternative method of connecting patients with specialty care. Specifically, a hybrid approach could be used to accomplish the myriad initial and follow-up tasks involved in the provision of amyloid-targeting therapies (Table). Not all VHA facilities possess the specialty expertise to prescribe these medications, and local clinicians may not have sufficient knowledge and clinical support to prescribe and monitor these therapies.

The first step is identifying local and regional subject matter experts, followed by the development and expansion of these networks. The National TeleNeurology Program is a good example of a national telehealth program that leverages technology to bring specialty services to rural areas with limited access to care. Although amyloid-targeting therapies often require more complex logistics, such as laboratory tests and imaging, these initial hurdles can be overcome through localized services and collaboration between VAMCs.

While treatment and imaging will most likely need to occur at a VAMC, most basic laboratory studies can be performed at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Some CBOCs may not be able to process more specialized laboratory tests such as apolipoprotein E genetic testing. Samples for these tests can be collected and processed at VAMCs, which usually have contracts with outside laboratories capable of performing these studies. Most, although not all, VAMCs offer advanced imaging, including MRI of the brain and amyloid PETs. VAMCs without those modalities may need to coordinate with other regional VAMCs. Additionally, a pilot program is already underway whereby VAMCs without the ability to quantify the amount of amyloid on PETs are able to leverage technology and collaborations with other VAMCs to obtain these data.

Once the initial phases of evaluation and care are completed, telemedicine can be leveraged for follow-up and ongoing management. Interdisciplinary teams can help facilitate care related to amyloid-targeting therapies, including the close monitoring of veterans for development of ARIA.15 To achieve this monitoring, specialty clinic teams prescribing amyloid-targeting therapies, which may be geographically distant, need to coordinate with local primary care clinical teams and emergency clinicians. All of these health care team members, along with neurologists and neurosurgeons, should be involved in the development and implementation of protocols in the event that patients present to their local primary or specialty care clinics or emergency department with ARIA symptoms.

If amyloid-targeting therapies are to be provided along with other emerging treatments for rural veterans, telehealth must be part of the solution. There is a pressing need to explore innovative evaluation and delivery models for these therapies, particularly as we expect additional diagnostics and therapeutics to be available in the future. With the advent of commercially available blood tests (ie, blood biomarkers) for AD, there is hope for a transition away from PETs and CSF testing given their cost, limited access, and invasiveness for diagnosis and monitoring of AD. These advances will increase the utility of telehealth to help rural veterans access amyloid-targeting therapies.

Additionally, administering the drug at home or at local clinics, supported by a dedicated health care team or home health agency, could further improve accessibility. Telehealth can be leveraged in this scenario, allowing specialty clinics and specialists to connect with patients and clinicians based out of local clinics or even home health agencies. In this scenario, specialists can provide hands-on care guidance and oversight even though they may be geographically distant from care recipients. Transitioning from IV administration to subcutaneous formulations would further enhance convenience and reduce barriers; these formulations may be available soon.16 Addressing logistical challenges to care and access through technology-based solutions will require coordinated efforts and continued VHA investment.

Conclusions

The VHA has a large population of veterans with dementia, and the costs to care for these veterans will only increase. While the current benefits of amyloid-targeting therapies are modest, now is the time to establish care processes that will support future innovations in amyloid-targeting therapies and other treatments and diagnostics. We are developing better ways to detect AD using clinical decision support tools, improving care pathways and the management of AD, and leveraging telehealth to improve access. The VA is conducting research to investigate whether a cognitive screening and laboratory evaluation that includes a telehealth preparedness assessment will be feasible and effective for improving the detection of AD and access to treatment, and we plan to publish the results.

The lessons learned can be extended to non-VHA care settings to help achieve potential benefits for other patients with early AD. Emerging therapies have the potential to improve the quality of life for both patients and care partners, adding life to years and not just years to life. Policymakers and payors must prioritize research funding to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches to the delivery of health services, ensuring that emerging therapies are accessible for all individuals affected by AD.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(4):e70235. doi:10.1002/alz.70235

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Statistical Projections of Alzheimer’s Dementia for VA Patients, VA Enrollees, and US Veterans. December 18, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_ALZHEIMERS_DEMENTIA_Statistical_Projections_FY21_and_FY33_sgc121820.pdf

- Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J. Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: are they effective? P T. 2010;35(4):208-211.

- Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, et al. Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):579-589. doi:10.3233/JAD-200133

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

- Tanne JH. Lecanemab: US Veterans Health Administration will cover cost of new Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ. 2023;380:p628. doi:10.1136/bmj.p628

- Nadeau SE. Lecanemab questions. Neurology. 2024;102(7):e209320. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209320 9. O’Donnell AJ, Fortunato AT, Spitznogle BL, et al. Implementation of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: facilitators and barriers. Presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago. May 2025.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- Hopp F, Whitten P, Subramanian U, et al. Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration about opportunities and barriers in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(8):404-409. doi:10.1258/135763306779378717

- VA reports significant increase in veteran use of telehealth services. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-reports-significant-increase-in-veteran-use-of-telehealth-services/

- Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, et al. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

- Erickson CM, Chin NA, Rosario HL, et al. Feasibility of virtual Alzheimer’s biomarker disclosure: findings from an observational cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9(3):e12413. doi:10.1002/trc2.12413

- Turk KW, Knobel MD, Nothern A, et al. An interprofessional team for disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer disease implementation. Neurol Clin Pract. 2024;14(6):e200346. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200346

- FDA accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) biologics license application for subcutaneous maintenance dosing for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Elsai US. January 13, 2025. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://media-us.eisai.com/2025-01-13-FDA-Accepts-LEQEMBI-R-lecanemab-irmb-Biologics-License-Application-for-Subcutaneous-Maintenance-Dosing-for-the-Treatment-of-Early-Alzheimers-Disease

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(4):e70235. doi:10.1002/alz.70235

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Statistical Projections of Alzheimer’s Dementia for VA Patients, VA Enrollees, and US Veterans. December 18, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_ALZHEIMERS_DEMENTIA_Statistical_Projections_FY21_and_FY33_sgc121820.pdf

- Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J. Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: are they effective? P T. 2010;35(4):208-211.

- Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, et al. Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):579-589. doi:10.3233/JAD-200133

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

- Tanne JH. Lecanemab: US Veterans Health Administration will cover cost of new Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ. 2023;380:p628. doi:10.1136/bmj.p628

- Nadeau SE. Lecanemab questions. Neurology. 2024;102(7):e209320. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209320 9. O’Donnell AJ, Fortunato AT, Spitznogle BL, et al. Implementation of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: facilitators and barriers. Presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago. May 2025.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- Hopp F, Whitten P, Subramanian U, et al. Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration about opportunities and barriers in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(8):404-409. doi:10.1258/135763306779378717

- VA reports significant increase in veteran use of telehealth services. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-reports-significant-increase-in-veteran-use-of-telehealth-services/

- Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, et al. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

- Erickson CM, Chin NA, Rosario HL, et al. Feasibility of virtual Alzheimer’s biomarker disclosure: findings from an observational cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9(3):e12413. doi:10.1002/trc2.12413

- Turk KW, Knobel MD, Nothern A, et al. An interprofessional team for disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer disease implementation. Neurol Clin Pract. 2024;14(6):e200346. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200346

- FDA accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) biologics license application for subcutaneous maintenance dosing for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Elsai US. January 13, 2025. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://media-us.eisai.com/2025-01-13-FDA-Accepts-LEQEMBI-R-lecanemab-irmb-Biologics-License-Application-for-Subcutaneous-Maintenance-Dosing-for-the-Treatment-of-Early-Alzheimers-Disease

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

Whole Health(y) Aging With Gerofit: The Development of a Pilot Wellness Program for Older Veterans

Whole Health(y) Aging With Gerofit: The Development of a Pilot Wellness Program for Older Veterans

About half of the > 9 million veterans served by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) are aged ≥ 65 years.1 Veterans are at a higher risk for comorbidities, which may contribute to increased health care costs, mobility limitations and disability, poor quality of life, and mortality. 2-5 Programs and policies that promote health maintenance, independent living, and quality of life are needed among older veterans. To support veterans’ overall health and well-being, the VHA has shifted to whole health, a patient-centered care model.6

The whole health paradigm employs personalized, proactive, and patient-driven care, emphasizing complementary and integrative health practices, and prioritizing health promotion and disease prevention over disease treatment.7 The veteran is empowered to decide “what matters to [me],” reflect on life and health, and define mission, aspiration, and purpose. This approach gives veterans a more active and direct role in their care, distinguishing it from traditional care models. In turn, it helps reduce the burden on clinicians and fosters a more collaborative environment in which both the clinician and veteran work together to shape the care process.7 Veterans utilize the Circle of Health to identify skills and support needed to implement changes in self-care. The Circle of Health includes 8 self-care components: moving the body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind.6 This process drives the creation of a personal health plan, creating opportunities for individuals to engage in well-being programs that matter to them and help them meet their goals.

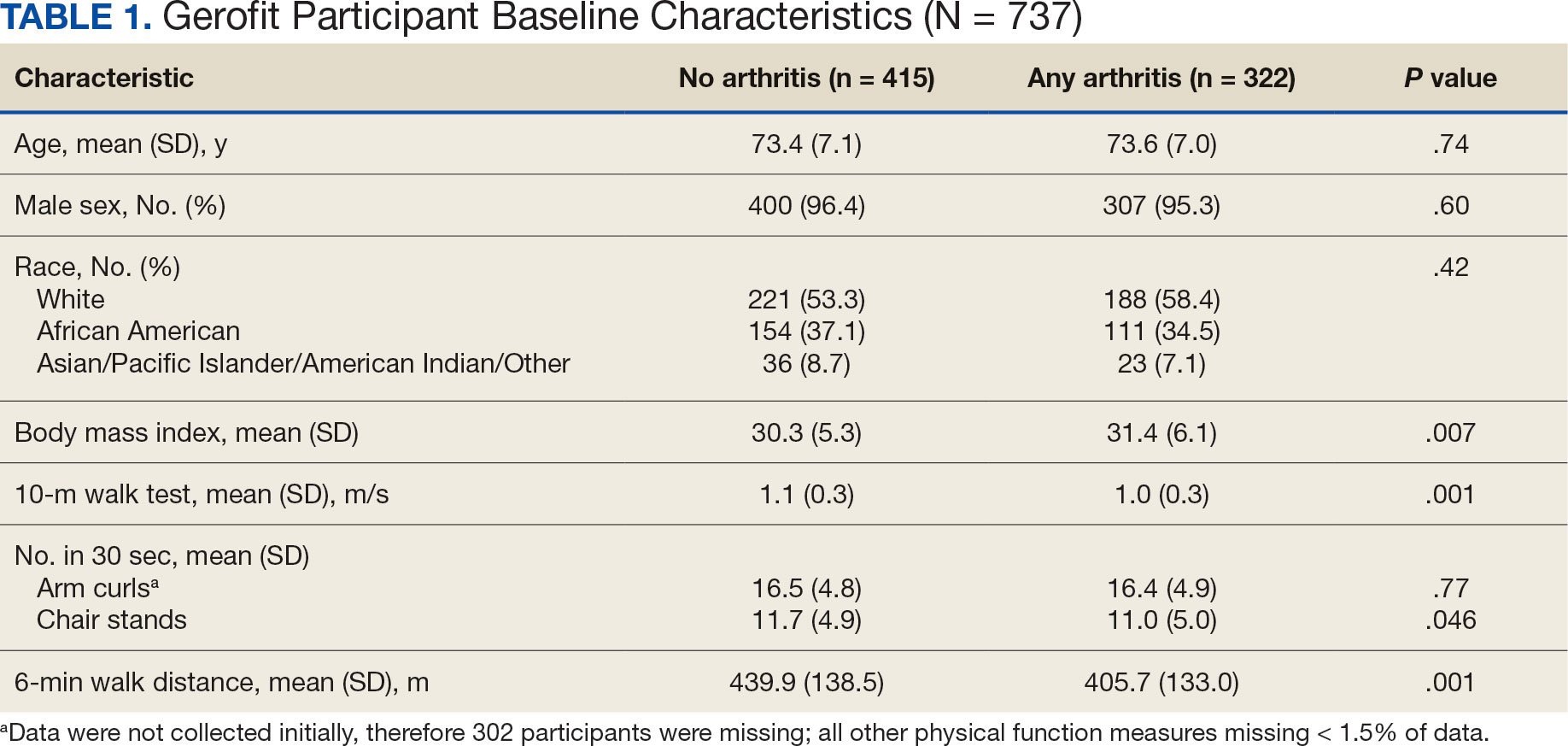

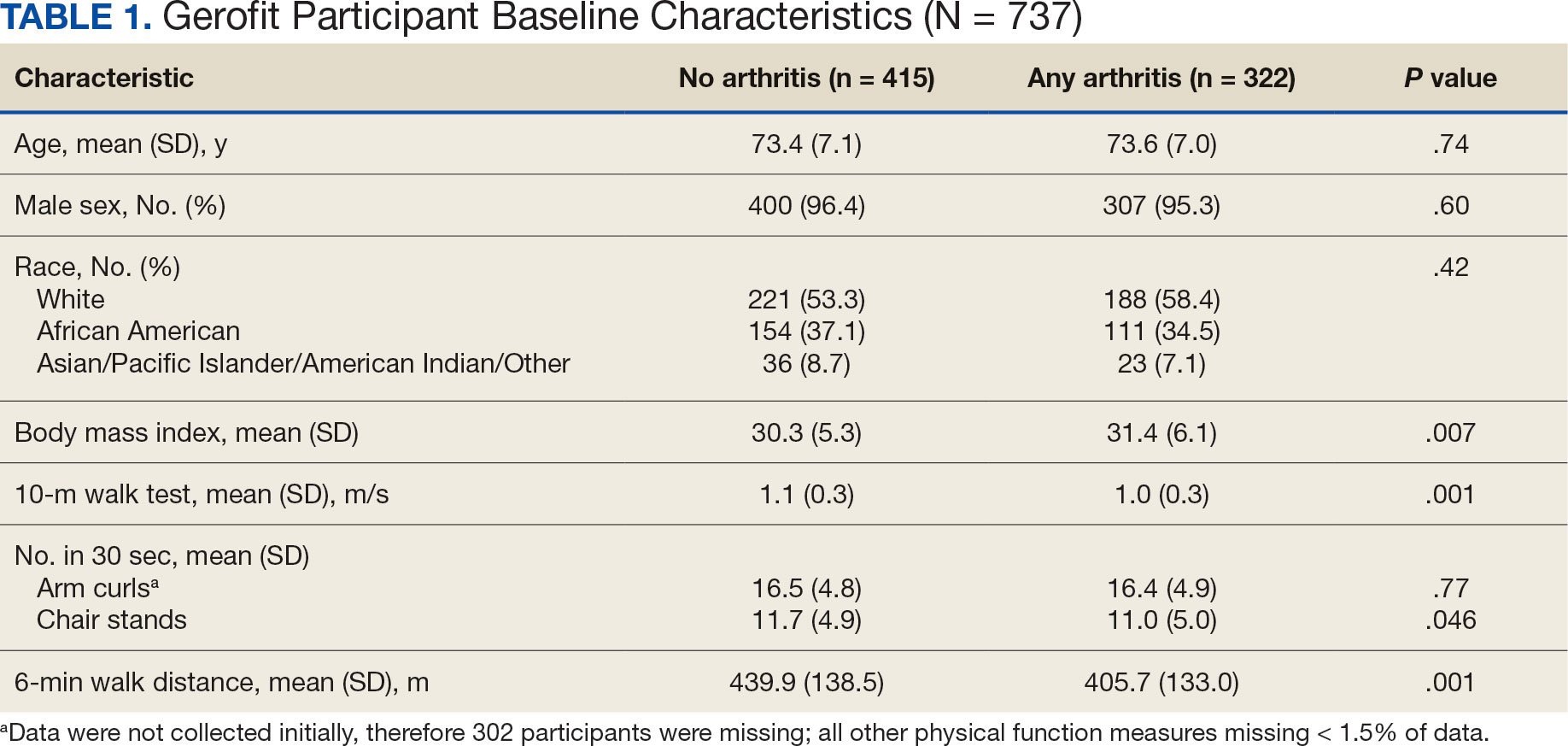

Gerofit is a VHA best practice and whole health outpatient exercise program for veterans aged ≥65 years.8 Gerofit has focused primarily on exercise within the moving the body self-care component.9 A longitudinal study followed 691 Gerofit participants across 6 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers who on average were 73 years old, had 16 different medical conditions, and took 10 medications. Most were obese and had a mean gait speed of 1.04 m/s, suggesting functional impairment.10 Prior studies have shown that Gerofit participation is associated with a range of health benefits. Two studies reported improvements in psychological well-being and sustained gains in endurance, strength, and flexibility following early Gerofit program participation. 11,12 A 10-year analysis of 115 veterans found that long-term Gerofit participation reduced mortality risk, while another study of 452 veterans showed decreased medication use following 1 year in the program.13,14

The VHA whole health model comprises 3 components: (1) The Pathway, (2) well-being programs, and (3) whole health clinical care.6 The Pathway engages veterans in identifying personal health goals, while well-being programs offer selfcare and skill-building activities. Traditional clinical settings often focus primarily on the third component due to time and resource constraints. The Gerofit platform addresses all 3 components. Its existing infrastructure, including a supportive community and dedicated facilities, provides a setting for implementing The Pathway and well-being programs. The Gerofit structure allows for the time and continuity necessary for these components, which are often limited during standard clinical visits.

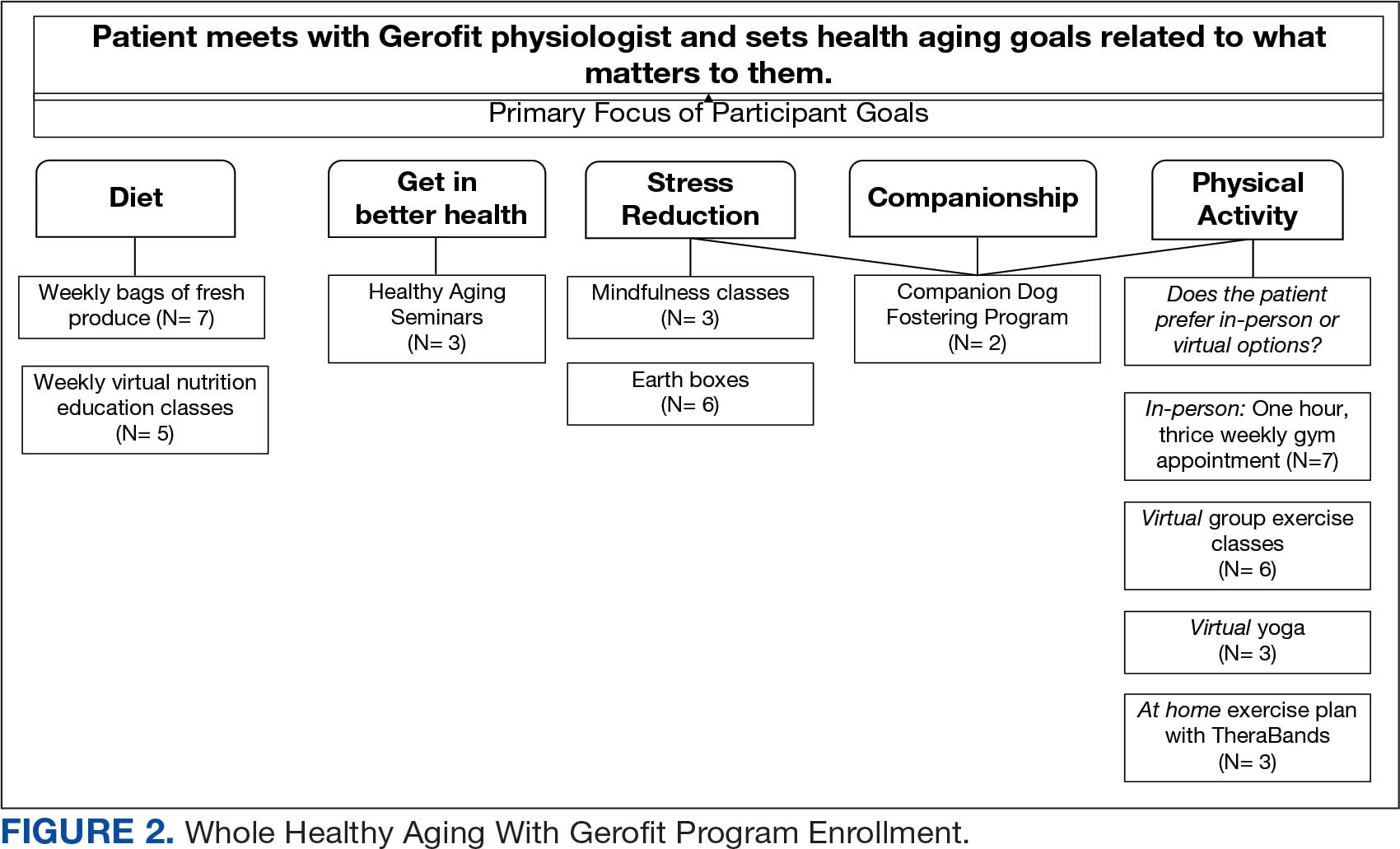

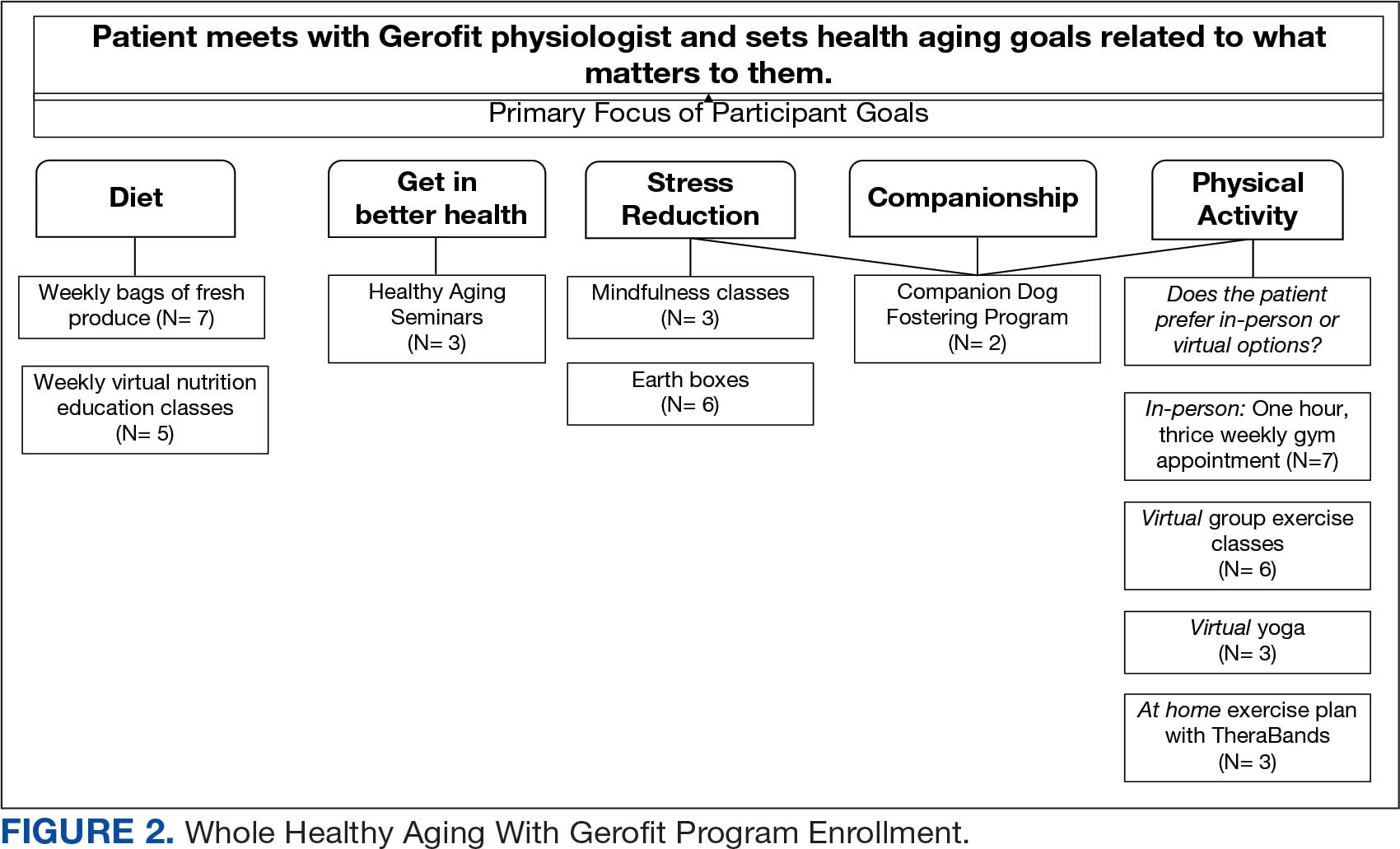

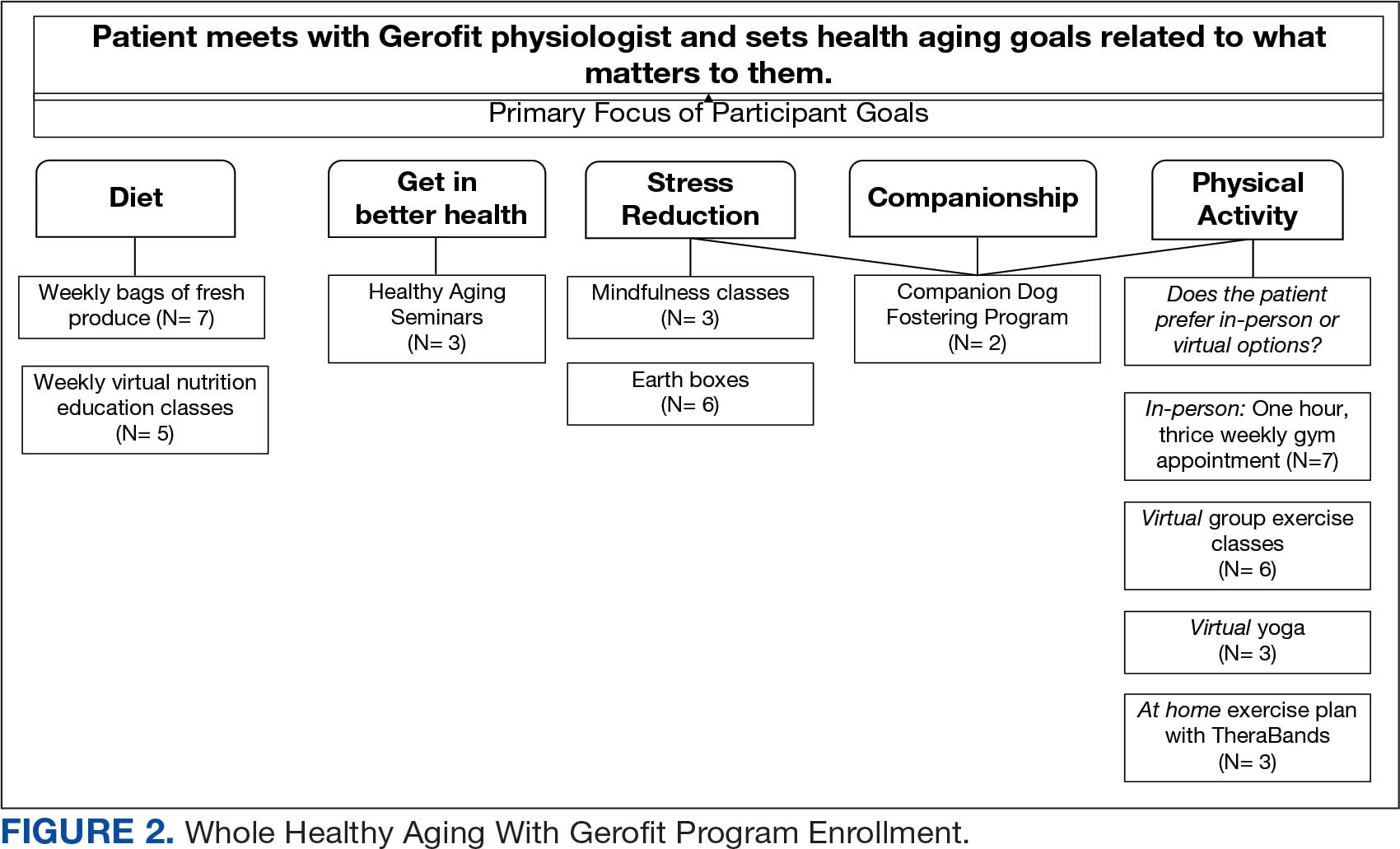

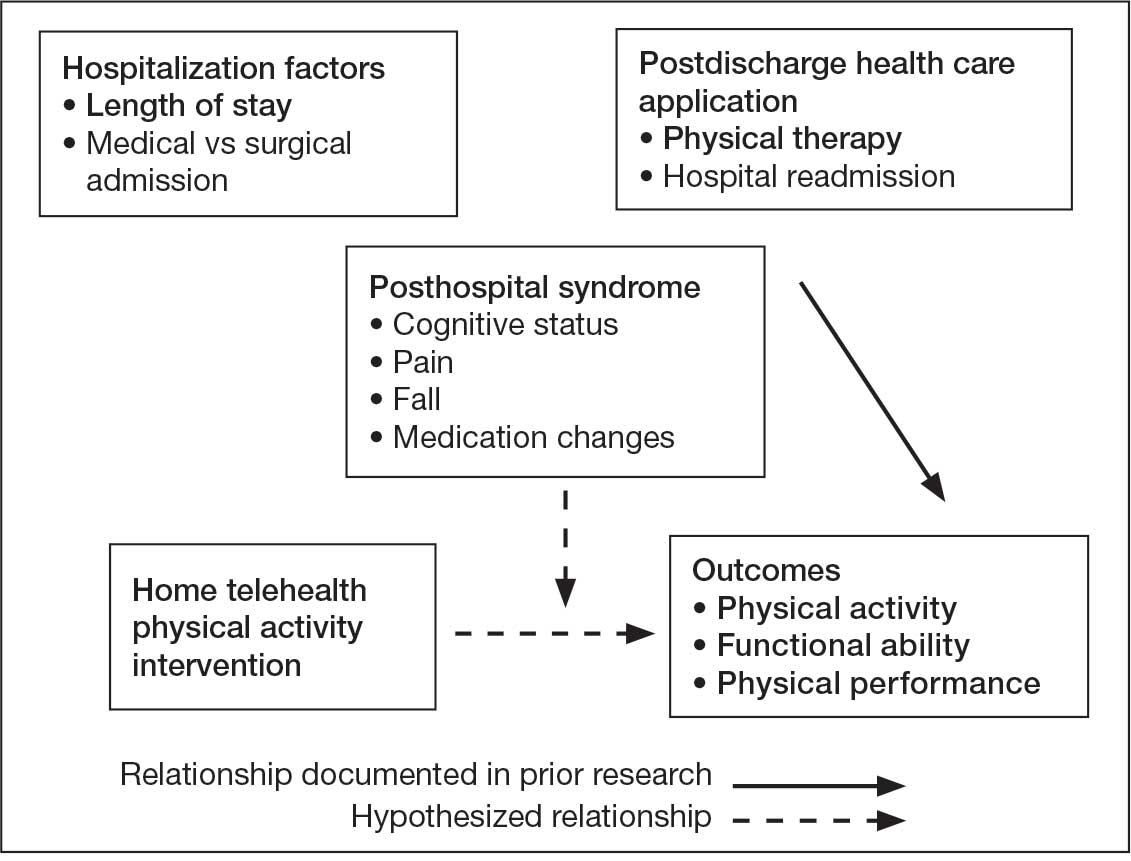

By expanding the Gerofit exercise regimen to include additional wellness activities, it can holistically support older veterans. Research supports this integrative approach. For example, a 2020 study found that incorporating a holistic health program into an existing exercise program within a church setting led to improved physical activity and overall health among women participants.15 This article describes the integration of Whole Health(y) Aging with Gerofit (WHAG), a pilot program in Baltimore, Maryland, that integrates whole health components into the established Gerofit framework to enhance the overall well-being of participating veterans (Figure 1).

WHOLE HEALTH(Y) AGING WITH GEROFIT

Gerofit enrollment has been described elsewhere in detail.16 Patients aged ≥ 65 years are eligible to participate with clinician approval if they are medically stable. Following VHA clinician referral and primary care approval, veterans completed a telephone visit to determine eligibility and discuss their exercise history, goals, and preferences. Veterans dependent in activities of daily living and those with cognitive impairment, unstable angina, active proliferative diabetic retinopathy, oxygen dependence, frank incontinence, active open wounds, active substance abuse, volatile behavioral issues, or who are experiencing homelessness are not eligible for Gerofit.

The exercise physiologist identified veteran barriers and incentives to participation and assisted with a plan to maximize SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound). Veterans then completed an assessment visit, either in person or virtually, depending on the selected programming. Functional assessments conducted by trained Gerofit exercise physiologists include testing of lower and upper body strength and submaximal endurance.9,17,18 Participation in Gerofit is voluntary and not time limited.

Prior to these newly expanded offerings, veterans could only enroll in a personalized, structured exercise program. Based on feedback from Gerofit participants indicating areas of interest, WHAG was developed to provide additional wellness offerings aligned with other Circle of Health components.6 This included virtual group nutrition education and cooking interventions with optional fresh produce delivery; wellness classes, the Companion Dog Fostering & Adoption program, and Gerofit in the Mind, which included mindfulness classes and relaxation seminars (Figure 1). Programs were virtual (except dog fostering and adoption) and rotated throughout the year. Not all programs are offered simultaneously.

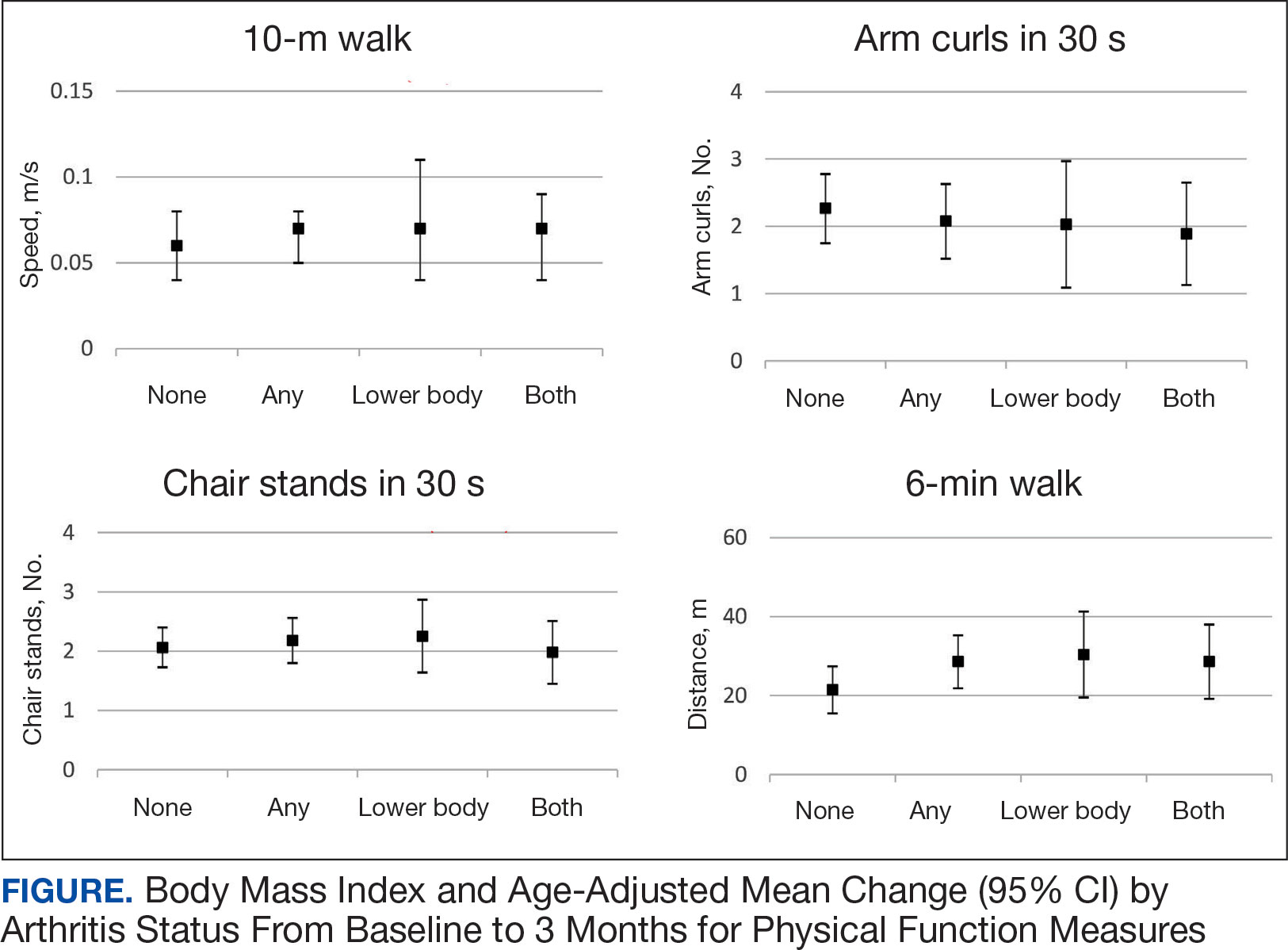

Attendance, completion of selected questions from the individual Personal Health Inventory (PHI) Short Form, measured physical function, self-reported physical activity levels, physical and mental health status, and program satisfaction were measured for all WHAG subprograms.18 Selected questions from the PHI Short Form use a 5-point Likert scale to rate the following whole health components: physical activity; sleep, relaxation, and recovery; healthy eating habits; and positive outlook, healthy relationships, and caring for mental health. Physical function was assessed using 30-second arm curls (upper body strength), 30-second chair stands (lower body strength), and the 2-minute step test (virtual) or 6-minute walk test (in person) (submaximal cardiovascular endurance).

Self-reported physical activity was assessed by asking frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per session) of cardiovascular and strength exercises to calculate total minutes per week. Physical and mental health status was assessed using the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health Scale.19 Demographic data included sex, race and ethnicity, and age at baseline visit. Mean (SD) was calculated for continuous variables and presented unless otherwise specified, and frequencies were calculated for categorical variables. Subsequent reports will describe additional assessments and detailed outcomes unique to individual programs.

Overview

Veterans chose the programs that best suited their needs without limitations.7 Staff provided guidance on newly available programs based on an individual’s specified goals. Gerofit staff assisted veterans with development of individualized personal health plans, monitoring progress towards their goals, supporting program participation, and connecting veterans with additional whole health resources.

Gerofit Exercise Group. Exercise was designed to address the Moving the Body component of whole health. Veterans could elect to schedule 1-hour, 3-times-weekly in-person gym appointments, participate in 3-times-weekly livestreamed virtual group exercise classes through VA Video Connect, or receive a self-directed at-home exercise plan.

Gerofit Learning Opportunities for Wellness Classes. These virtual health education sessions addressed the personal development component of whole health and were designed to increase self-efficacy and empower veterans to take an active role in their health care. Topics focused broadly on issues related to healthy aging (eg, importance of sleep, goal setting, self-care, and comorbidity education). Veterans could participate in any classes of interest, which were led by health care professionals and offered twice monthly. Sessions encouraged participant questions and peer interaction.

Nutrition. Improving dietary quality is a frequently reported goal of Gerofit participants. WHAG incorporated multiple strategies to assist veterans in meeting these goals. For example, through a partnership with Therapeutic Alternative of Maryland Farm, Gerofit provided veterans free, locally grown fresh produce. This initiative addressed barriers to healthy eating by improving access to fresh produce, which has been shown to influence cooking frequency and diet quality.20-22 Participation in nutrition classes was not required. In 2021, veterans received produce weekly; however, many reported excess quantities. Beginning in 2022, veterans could select both produce items and quantities desired.

In addition, a registered dietitian led a 14-week virtual nutrition education program guided by the social cognitive theory framework and focused on self-regulation skills such as goal setting, overcoming barriers, and identifying triggers.23 Prior research highlighted low health literacy as a common barrier among older veterans, which informed several key components of the curriculum.24 These included how to read and interpret nutrition labels, define balanced meals and snacks, and understand the classification of various food groups such as fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. The online program curriculum included an instructor guide and participant materials for each individual lesson, including an educational handout on the specific week’s topic, applied activity (group or individual), and recipes related to the produce shares. Structured group discussion promoted camaraderie and recipe sharing, and additional instruction on produce preparation and storage.

Reported lack of self-efficacy and knowledge regarding produce preparation prompted a 5-week virtual cooking series, led by a medical student and supervised by a registered dietitian. Sessions combined brief nutrition education with live cooking demonstrations adapted from the VA Healthy Teaching Kitchen curriculum. Recipes emphasized low-cost, commonly found food items. The Healthy Teaching Kitchen modifications focused on Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diets, diabetes, and the importance of protein for older adults. Participants were allowed time to discuss recipes and food preparation tips, and other household members were allowed to observe.

Dog Fostering and Adoption. Veterans could foster or adopt a rescue dog through a partnership with local rescue groups. This program allowed participating veterans to have a companion, which addressed the surroundings, moving the body, and spirit and soul whole health components. The Companion Dog Fostering and Adoption Program and results on physical function and daily physical activity from the first 3 months were recently published. Positive effects on physical activity, physical function, and quality of life were observed at 3 months as compared to baseline in veterans who received a companion dog.25

Gerofit in the Garden. Veterans could opt to receive an EarthBox containing soil and seedlings for 1 vegetable and 1 herb. The boxes are designed to fit on a small tabletop, regardless of home type or availability of backyard. In-person instruction for veterans on care and maintenance was provided by a farm employee with experience in gardening and farming practices.

Gerofit in the Mind. Online relaxation seminars were offered twice monthly for 4 months. Led by a certified sound health guide, sessions incorporated sound baths, crystal bowls, Tibetan bowls, tuning forks, and breath work. Virtual mindfulness classes led by a certified yoga instructor were offered weekly for 1 month. Veterans could drop in and participate based on their availability. Classes were designed to introduce veterans to the practice of mindfulness, improve mood, and lower stress and anxiety.

Pilot Program Outcomes

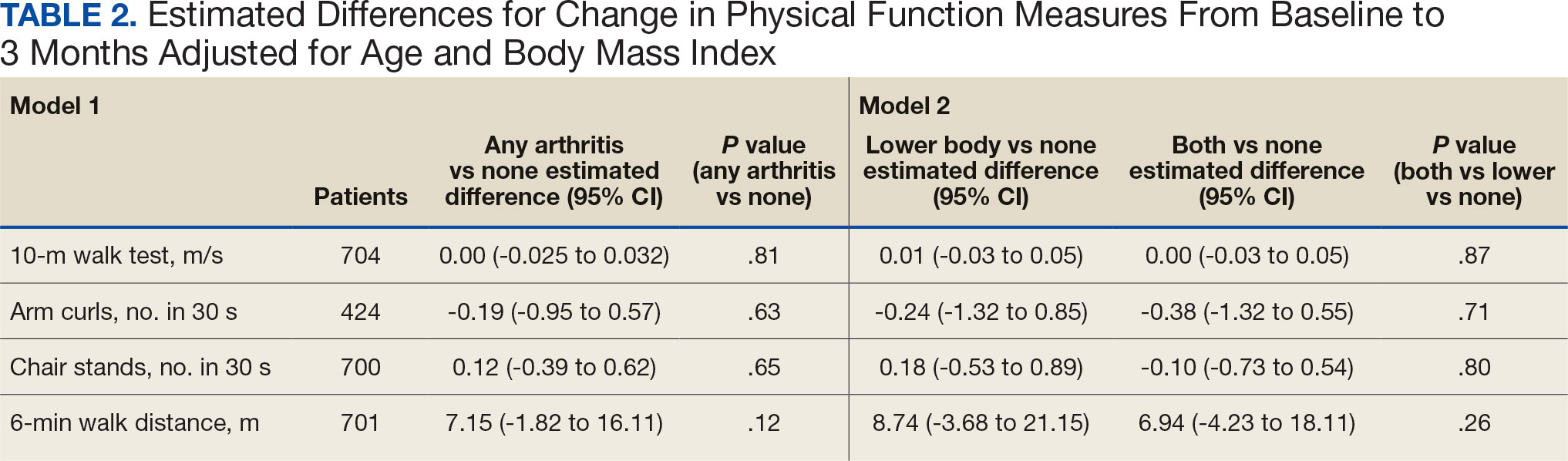

Sixteen male veterans participated in WHAG. Participants were 62% Black, with a mean age of 76 years. Veterans collaborated with Gerofit staff to develop personal health plans, which ultimately guided program participation (Figure 2).

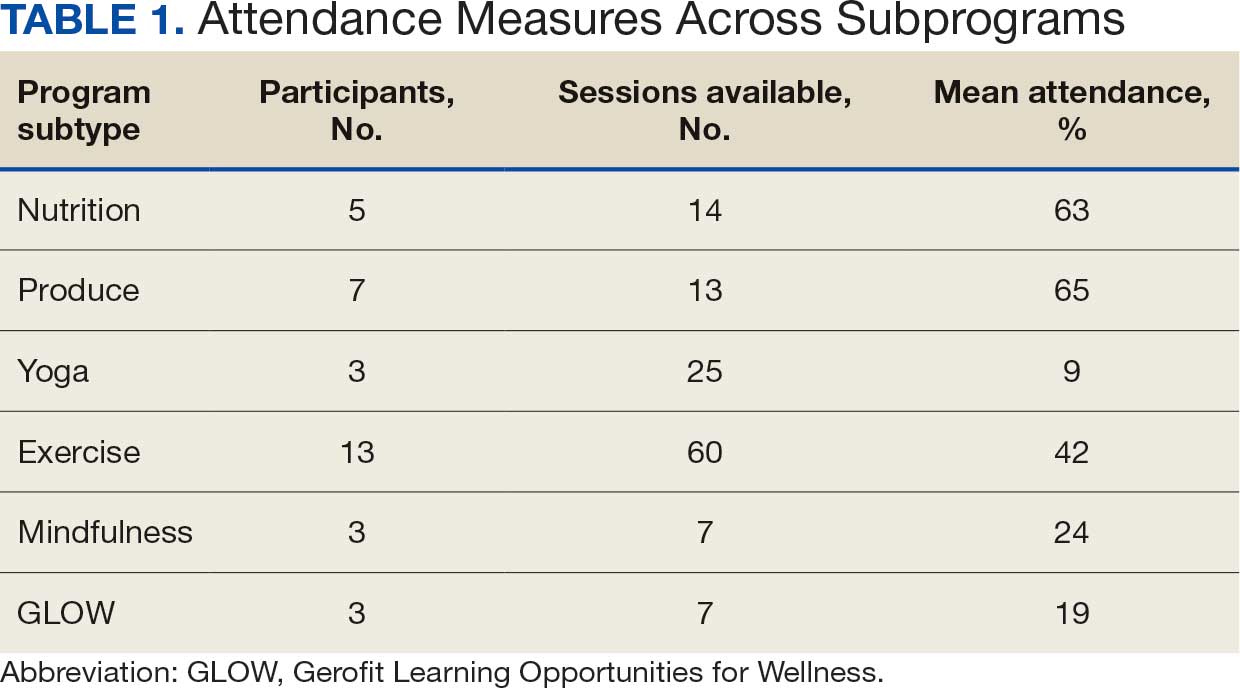

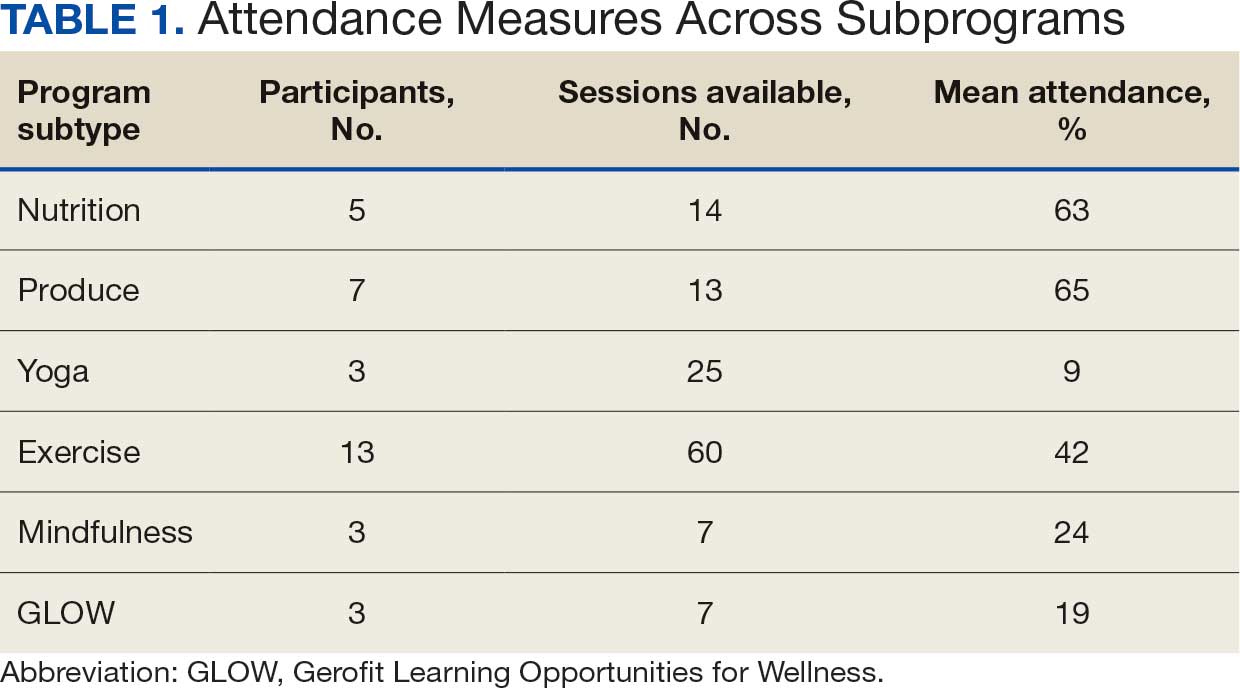

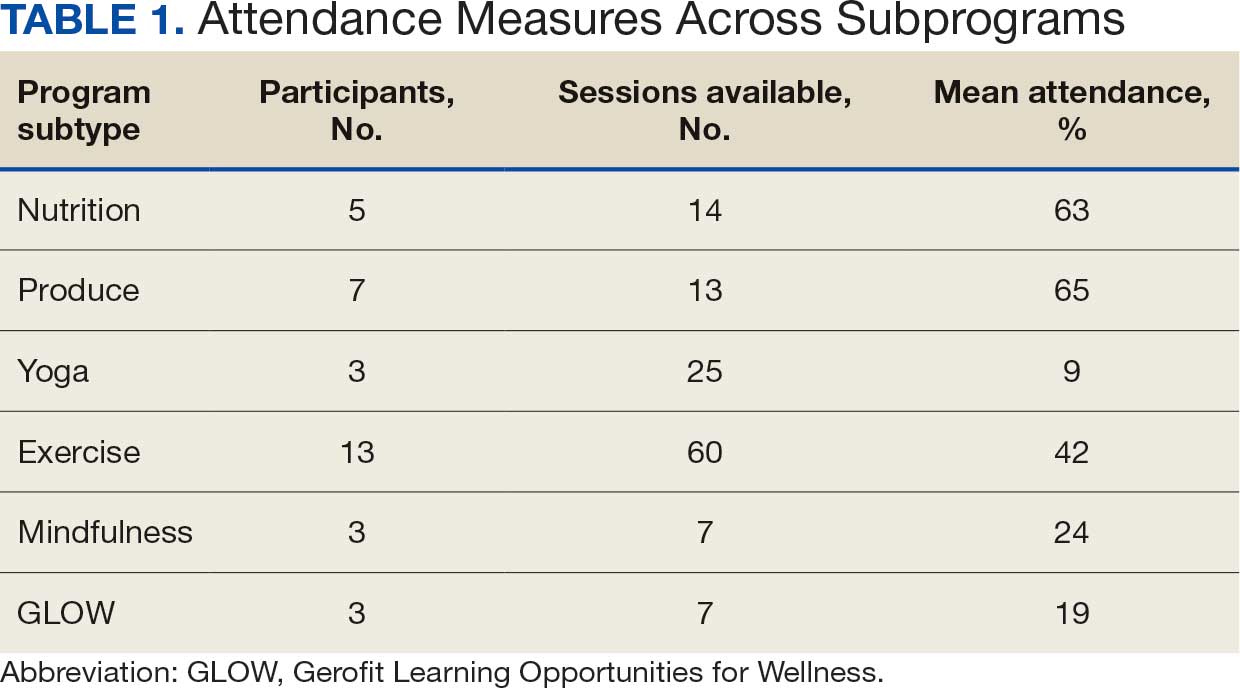

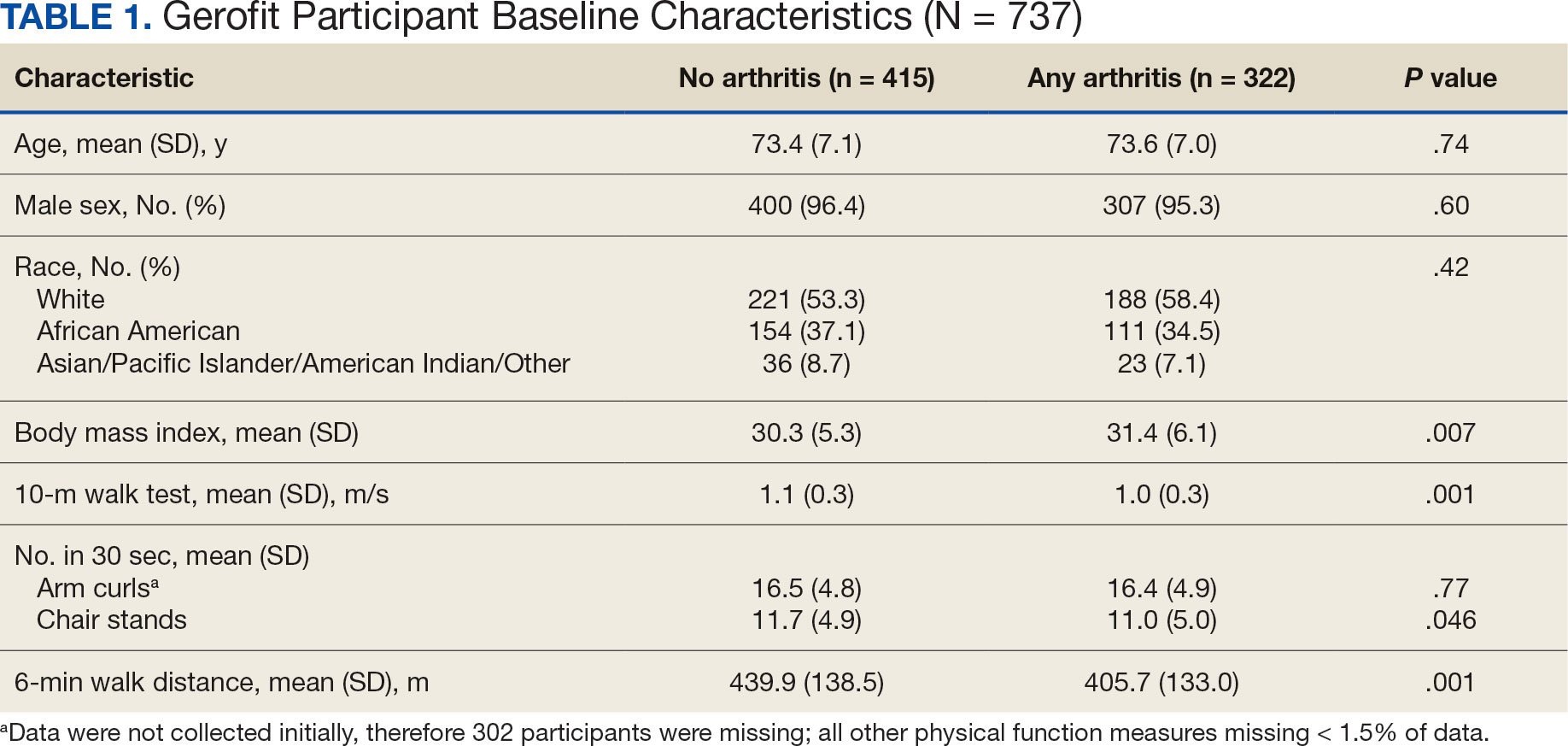

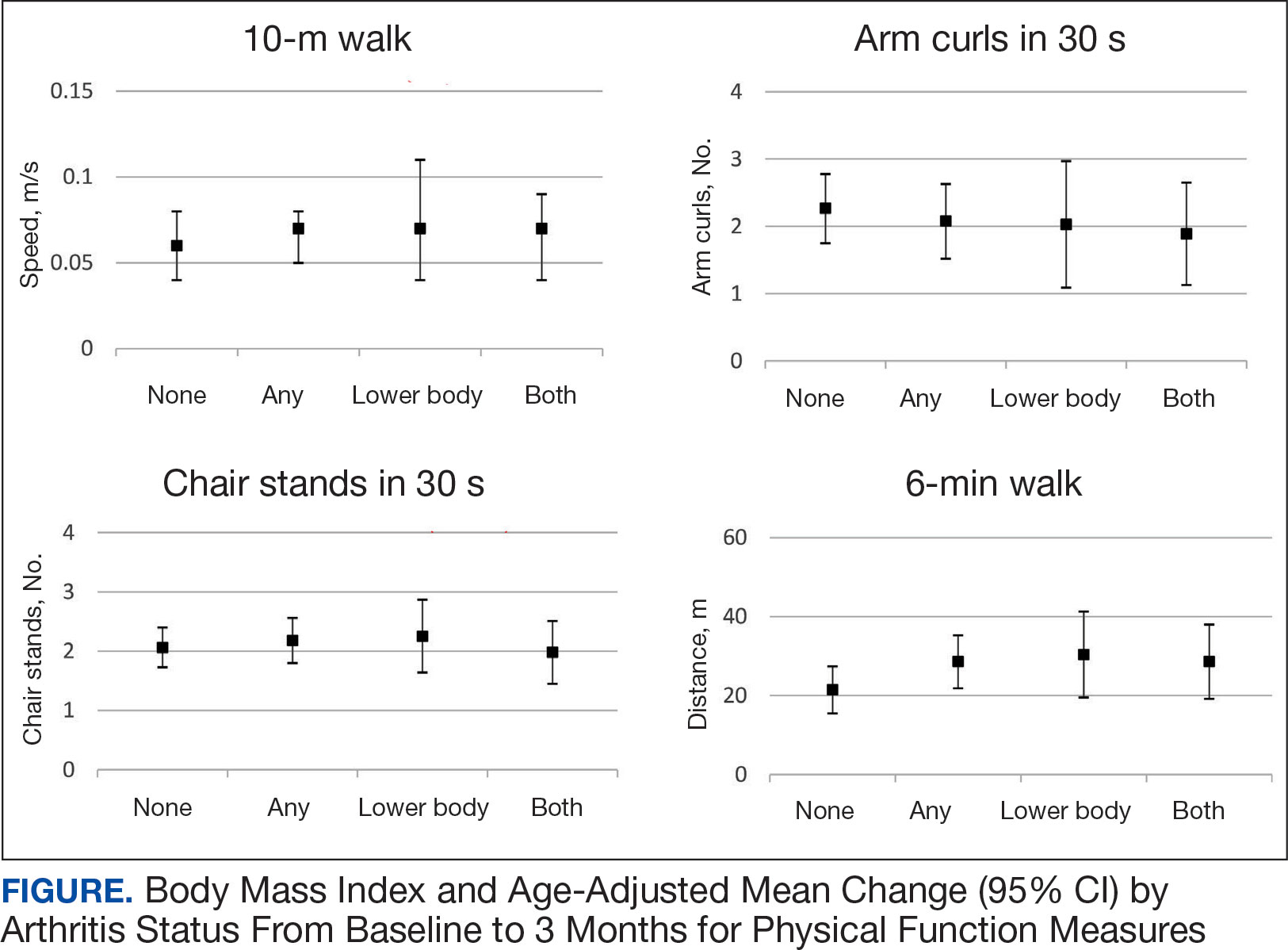

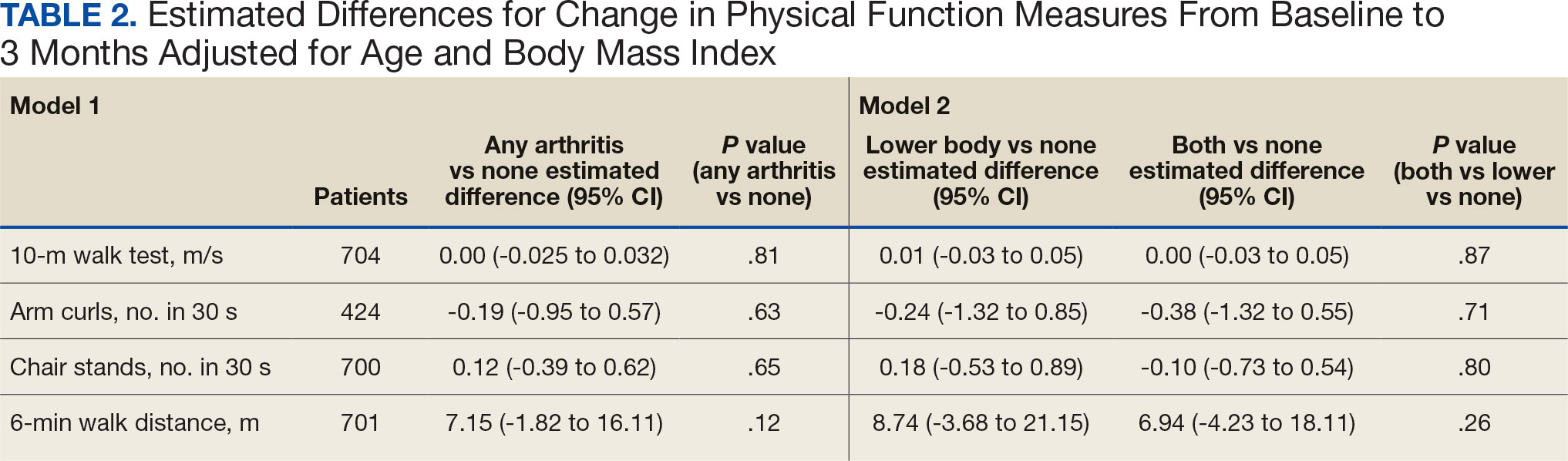

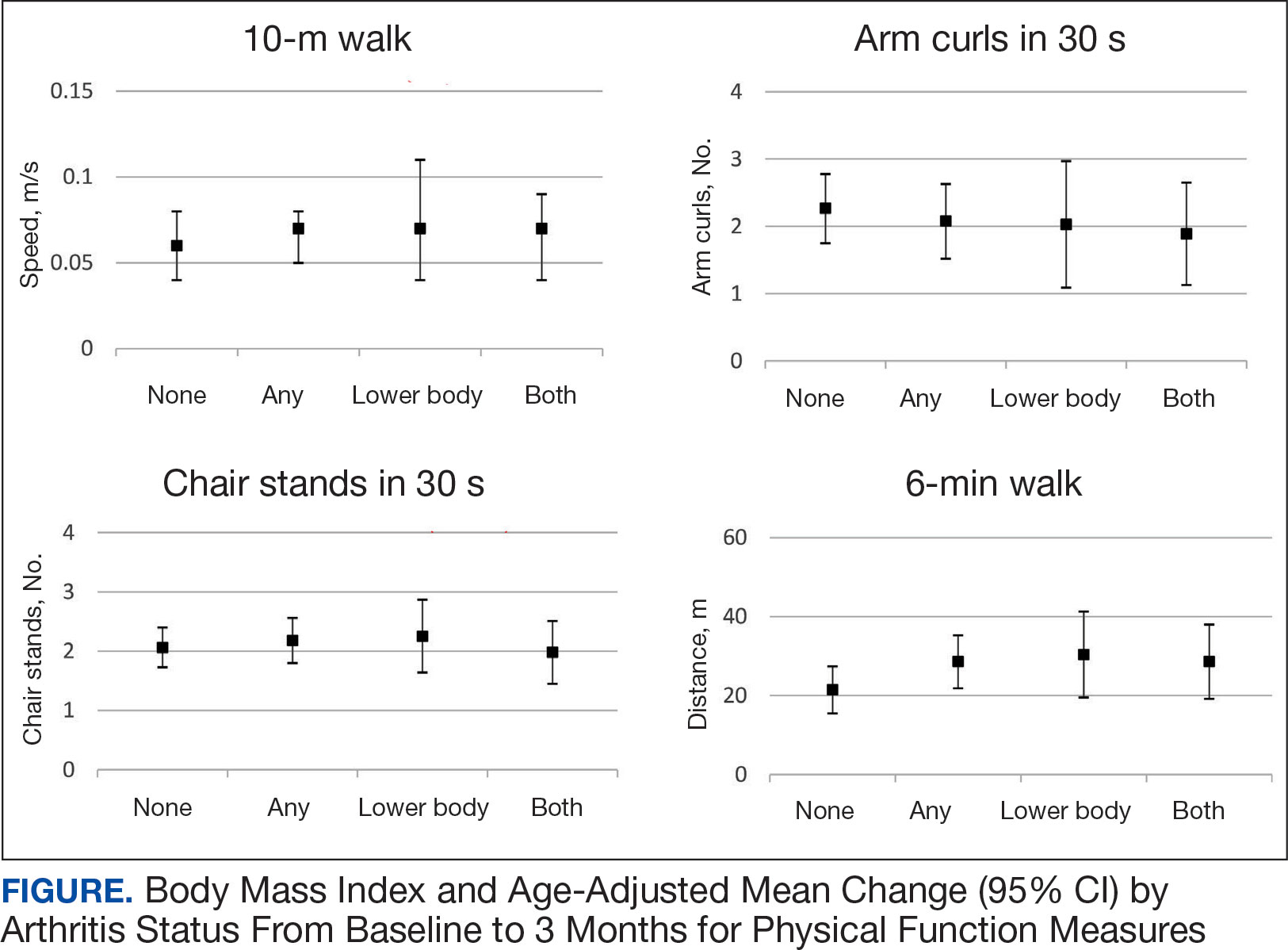

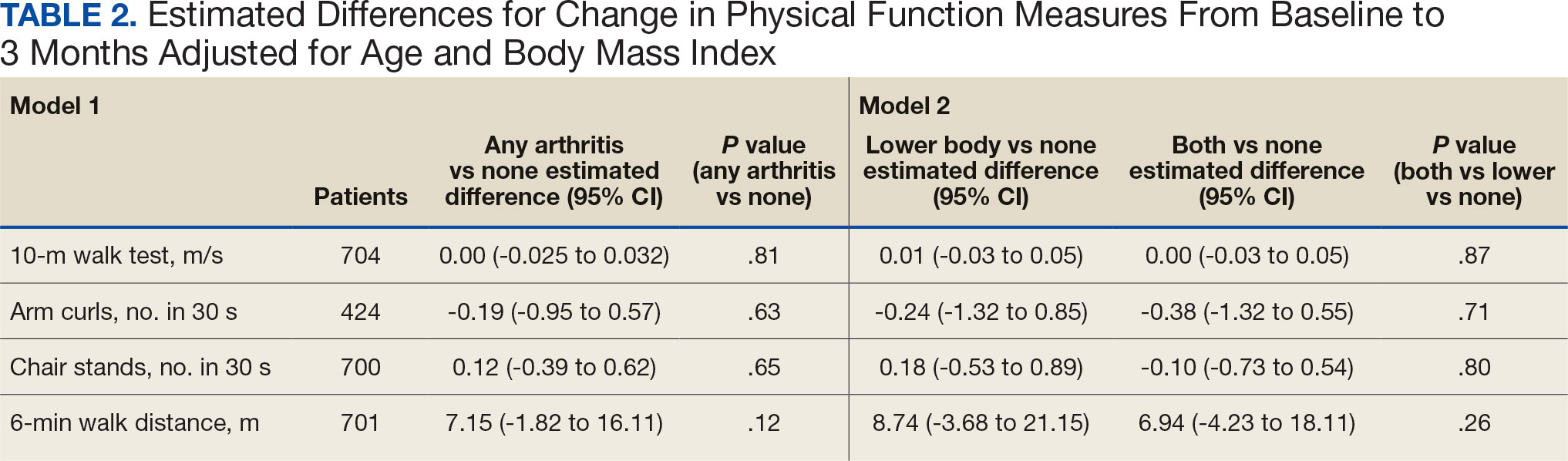

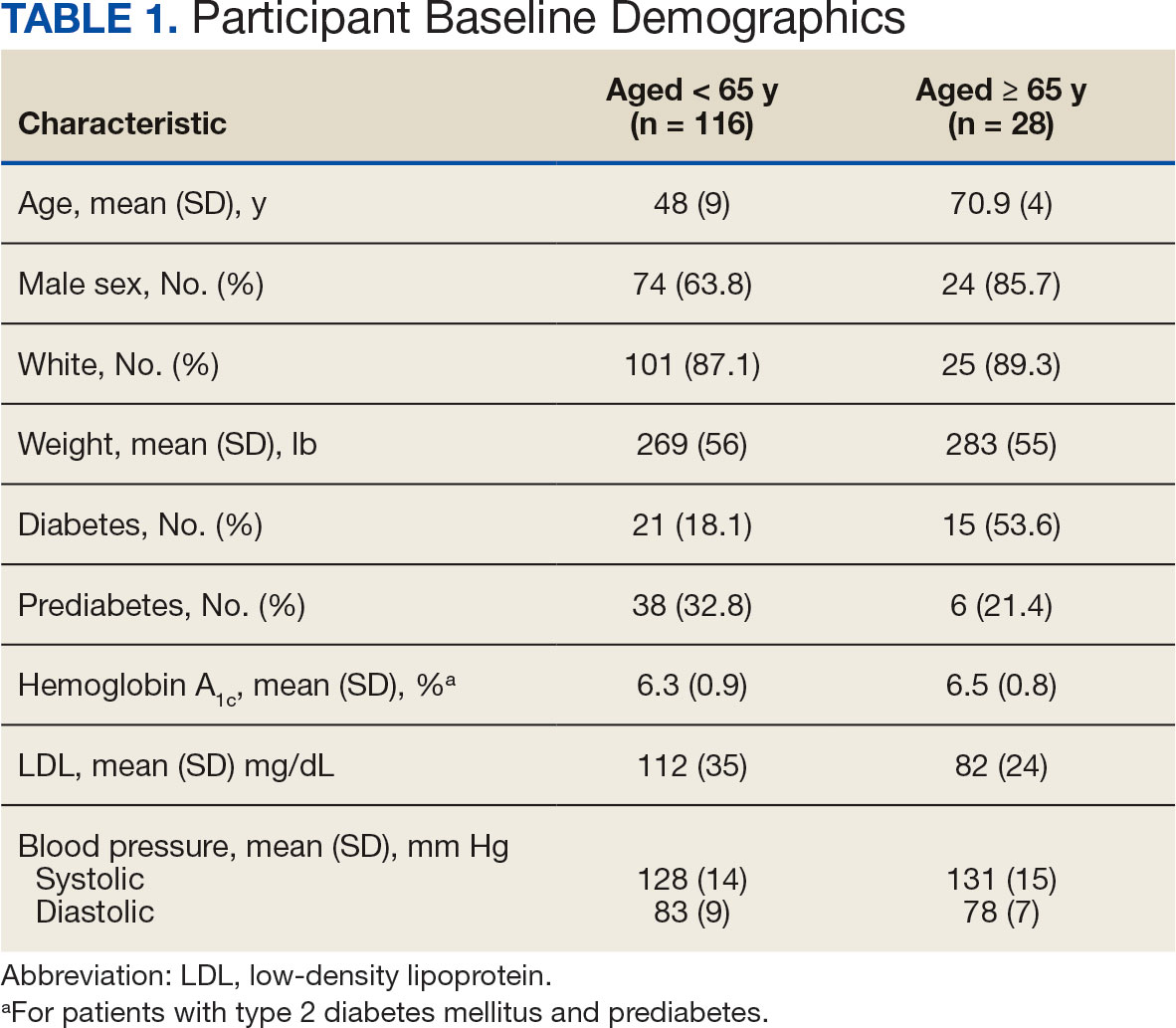

Five participants enrolled in 1 WHAG program, 11 enrolled in 2, and 8 enrolled in ≥ 3 (Table 1). Sixteen veterans completed baseline testing and 12 completed 3-month follow-up assessments (Table 2). At baseline, participants were below the reference range for physical functioning and physical activity levels. After 3 months, improvements were observed in endurance self-reported physical activity, and strength with many values in the reference range. However, physical and mental global health scores did not change.

Ten veterans completed the PHI Short Form. Veterans most frequently identified multiple areas they wished to improve, including moving the body (n = 10), recharge (n = 10), food and drink (n = 9), and power of the mind (n = 7). Baseline self-ratings on each whole health component, along with follow-up ratings at the program’s conclusion, are presented in Figure 3. Some participants aimed to maintain current levels rather than seek improvement. At the 3-month mark, most veterans perceived themselves as improving in ≥1 health component.

Discussion Programs that target holistic wellness are needed to ensure the health of a rapidly aging population. The WHAG pilot program is an example of a comprehensive, patient-centered wellness program that supports participants in defining personal wellness goals to promote healthy aging. Gerofit addresses the continuum by beginning with goal-oriented discussions with veterans to guide program participation and support desired outcomes.

Gerofit provided a strong pre-existing framework of virtual social support and physical infrastructure for the addition of WHAG. Gerofit staff were responsible for recruitment and engagement, program oversight, and outcome data collection. Additionally, VHA facilities provide physical space for in-person and virtual programming. Integrating WHAG into Gerofit allows veterans to prioritize “what matters” and engage with peers in a nontraditional way, such as the dog fostering and adoption program provides veterans with an opportunity to increase physical activity levels and improve mental and physical health through the human-animal bond.25

By providing virtual options, WHAG enhances access to health care in medically underserved areas. WHAG also improves the veteran experience with the VA, building on Gerofit’s track record of high patient satisfaction, strong adherence, high retention, and consistent consults for veterans to join.10 The program allows veterans to be at the forefront of their VHA care, choosing to participate in the various offerings based on their personal preferences.

In this population of older veterans from Baltimore, Maryland, the majority of whom reside in disadvantaged areas, we observed that the programs with the highest participation were related to diet, stress reduction, and physical activity. These 3 areas align with common barriers faced by individuals in underserved communities. Many of these communities are food deserts, lack space or resources for gardening, and have limited or unsafe access to opportunities for physical activity, making gyms or even neighborhood exercise difficult to access.26-28 Offering produce delivery and virtual nutrition classes may potentially alleviate this barrier by providing economic stability by increasing access to healthy foods paired with nutrition education to promote use of free, fresh food. Teaching older adults with impaired mobility how to overcome barriers to consuming a healthy diet may improve their dietary intake.23,29,30 Future evaluations aim to examine how these various nutrition programs impact dietary intake and how changes in dietary intake may impact functional outcomes among this group.

Group classes provide opportunities for social connection and mutual support, both of which are powerful motivators for older adults. Frequent contact with others may help reduce the risk of depression, loneliness, and social isolation.28 Routine contact with staff allows for observation of short-term changes in behavior and mood, giving staff the chance to follow up when needed. The addition of these new programs gives participants more opportunities to engage with Gerofit staff and fellow veterans beyond traditional exercise sessions. This WHAG model could expand to other Gerofit sites; however, future whole health programs should take into account the unique needs and barriers specific to each location. Doing so will help ensure offerings align with participant preferences. Programs should be thoughtfully selected and designed to directly address local challenges to promote optimal engagement and support the greatest potential for success.

CONCLUSIONS

Programs that promote and support functional independence in older adults are needed, particularly given the rapidly growing and aging population. Identifying comprehensive strategies that promote healthy aging is likely to be beneficial not only for chronic disease management and social engagement but may also promote functional independence and reduce the risk of further functional decline.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration– About VHA. Veterans Health Administration. 2023. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:915- 919. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Koepsell TD, Forsberg CW, Littman AJ. Obesity, overweight, and weight control practices in U.S. veterans. Prev Med. 2009;48:267-271. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.01.008

- Das SR, Kinsinger LS, Yancy WS Jr, et al. Obesity prevalence among veterans at Veterans Affairs medical facilities. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:291-294. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.007

- Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, et al. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, et al. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a whole health system of care: time for action and research. Med Care. 2020;58:295-300. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316

- Marchand WR, Beckstrom J, Nazarenko E, et al. The Veterans Health Administration whole health model of care: early implementation and utilization at a large healthcare system. Mil Med. 2020;185:2150-2157. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa198

- Shulkin D, Elnahal S, Maddock E, Shaheen M. Best Care Everywhere by VA Professionals Across the Nation. US Dept of Veterans Affairs; 2017.

- Morey MC, Lee CC, Castle S, et al. Should structured exercise be promoted as a model of care? Dissemination of the Department of Veterans Affairs Gerofit Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1009-1016. doi:10.1111/jgs.15276

- Cowper PA, Morey MC, Bearon LB, et al. The impact of supervised exercise on the psychological well-being and health status of older veterans. J Appl Gerontol. 1991;10:469-485. doi:10.1177/073346489101000408

- Pepin MJ, Valencia WM, Bettger JP, et al. Impact of supervised exercise on one-year medication use in older veterans with multiple morbidities. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420956751. doi:10.1177/073346489101000408

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sullivan RJ Jr, et al. Fiveyear performance trends for older exercisers: a hierarchical model of endurance, strength, and flexibility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1226-1231. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01374.x

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Crowley GM, et al. Exercise adherence and 10-year mortality in chronically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1929-1933. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50602.x

- Jorna M, Ball K, Salmon J. Effects of a holistic health program on women’s physical activity and mental and spiritual health. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:395-401. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.06.011

- Jennings SC, Manning KM, Bettger JP, et al. Rapid transition to telehealth group exercise and functional assessments in response to COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420980313. doi:10.1177/2333721420980313

- Morey MC, Crowley GM, Robbins MS, et al. The Gerofit program: a VA innovation. South Med J. 1994;87:S83-87.

- Addison O, Serra MC, Katzel L, et al. Mobility improvements are found in older veterans after 6 months of Gerofit regardless of BMI classification. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27:848-854. doi:10.1123/japa.2018-0317

- Veterans Health Administration Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. Making your plan— whole health. November 14, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/phi.asp

- Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:873-880. doi:10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9

- Aktary ML, Caron-Roy S, Sajobi T, et al. Impact of a farmers’ market nutrition coupon programme on diet quality and psychosocial well-being among low-income adults: protocol for a randomised controlled trial and a longitudinal qualitative investigation. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035143. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035143

- Afshin A, Penalvo JL, Del Gobbo L, et al. The prospective impact of food pricing on improving dietary consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172277. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172277

- Singleton CR, Kessee N, Chatman C, et al. Racial/ ethnic differences in the shopping behaviors and fruit and vegetable consumption of farmers’ market incentive program users in Illinois. Ethn Dis. 2020;30:109. doi:10.18865/ed.30.1.109

- Cassatt S, Giffuni J, Ortmeyer H, et al. A pilot study to evaluate the development and implementation of a virtual nutrition education program in older veterans. Abstract presented at: American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2022 Scientific Sessions; March 1-4, 2022; Chicago, IL. https:// www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.145.suppl_1.P002

- Parker EA, Perez WJ, Phipps B, et al. Dietary quality and perceived barriers to weight loss among older overweight veterans with dysmobility. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:9153. doi:10.3390/ijerph19159153

- Ortmeyer HK, Giffuni J, Etchberger D, et al. The role of companion dogs in the VA Maryland Health Care System Whole Health(y) GeroFit Program. Animals (Basel). 2023;13:19. doi:10.3390/ani13193047

- Milaneschi Y, Tanaka T, Ferrucci L. Nutritional determinants of mobility. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:625- 629.

- Lane JM, Davis BA. Food, physical activity, and health deserts in Alabama: the spatial link between healthy eating, exercise, and socioeconomic factors. GeoJournal. 2022;87:5229-5249.

- Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Saito Y, et al. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:190. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0584-3

- Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Saito Y, et al. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:190. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0584-3

- Wolfson JA, Ramsing R, Richardson CR, et al. Barriers to healthy food access: associations with household income and cooking behavior. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:298-305. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.01.023

About half of the > 9 million veterans served by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) are aged ≥ 65 years.1 Veterans are at a higher risk for comorbidities, which may contribute to increased health care costs, mobility limitations and disability, poor quality of life, and mortality. 2-5 Programs and policies that promote health maintenance, independent living, and quality of life are needed among older veterans. To support veterans’ overall health and well-being, the VHA has shifted to whole health, a patient-centered care model.6

The whole health paradigm employs personalized, proactive, and patient-driven care, emphasizing complementary and integrative health practices, and prioritizing health promotion and disease prevention over disease treatment.7 The veteran is empowered to decide “what matters to [me],” reflect on life and health, and define mission, aspiration, and purpose. This approach gives veterans a more active and direct role in their care, distinguishing it from traditional care models. In turn, it helps reduce the burden on clinicians and fosters a more collaborative environment in which both the clinician and veteran work together to shape the care process.7 Veterans utilize the Circle of Health to identify skills and support needed to implement changes in self-care. The Circle of Health includes 8 self-care components: moving the body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind.6 This process drives the creation of a personal health plan, creating opportunities for individuals to engage in well-being programs that matter to them and help them meet their goals.

Gerofit is a VHA best practice and whole health outpatient exercise program for veterans aged ≥65 years.8 Gerofit has focused primarily on exercise within the moving the body self-care component.9 A longitudinal study followed 691 Gerofit participants across 6 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers who on average were 73 years old, had 16 different medical conditions, and took 10 medications. Most were obese and had a mean gait speed of 1.04 m/s, suggesting functional impairment.10 Prior studies have shown that Gerofit participation is associated with a range of health benefits. Two studies reported improvements in psychological well-being and sustained gains in endurance, strength, and flexibility following early Gerofit program participation. 11,12 A 10-year analysis of 115 veterans found that long-term Gerofit participation reduced mortality risk, while another study of 452 veterans showed decreased medication use following 1 year in the program.13,14