User login

- Assess asthma severity before initiating treatment; monitor asthma control to guide adjustments in therapy using measures of impairment (B) and risk (C) (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI] and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program [NAEPP] third expert panel report [EPR-3]).

- Base treatment decisions on recommendations specific to each age group (0-4 years, 5-11 years, and ≥12 years) (A).

- Use spirometry in patients ≥5 years of age to diagnose asthma, classify severity, and assess control (C).

- Provide each patient with a written asthma action plan with instructions for daily disease management, as well as identification of, and response to, worsening symptoms (B).

EPR-3 evidence categories:

- Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs), rich body of data

- RCTs, limited body of data

- Nonrandomized trials and observational studies

- Panel consensus judgment

JJ, a 4-year-old boy, was taken to an urgent care clinic 3 times last winter for “recurrent bronchitis” and given a 7-day course of prednisone and antibiotics at each visit. His mother reports that “his colds always seem to go to his chest” and his skin is always dry. She was given a nebulizer and albuterol for use when JJ begins wheezing, which often happens when he has a cold, plays vigorously, or visits a friend who has cats.

JJ is one of approximately 6.7 million children—and 22.9 million US residents—who have asthma.1 To help guide the care of patients like JJ, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) released the third expert panel report (EPR-3) in 2007. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm, the EPR-3 provides the most comprehensive evidence-based guidance for the diagnosis and management of asthma to date.2

The guidelines were an invaluable resource for JJ’s family physician, who referred to them to categorize the severity of JJ’s asthma as “mild persistent.” In initiating treatment, JJ’s physician relied on specific recommendations for children 0 to 4 years of age to prescribe low-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). Without the new guidelines, which underscore the safety of controller medication for young children, JJ’s physician would likely have been reluctant to place a 4-year-old on ICS.

This review highlights the EPR-3’s key recommendations to encourage widespread implementation by family physicians.

The EPR-3: What’s changed

The 2007 guidelines:

Recommend assessing asthma severity before starting treatment and assessing asthma control to guide adjustments in treatment.

Address both severity and control in terms of impairment and risk.

Feature 3 age breakdowns (0-4 years, 5-11 years, and ≥12 years) and a 6-step approach to asthma management.

Make it easier to individualize and adjust treatment.

What’s changed?

There’s a new paradigm

The 2007 update to guidelines released in 1997 and 2002 reflects a paradigm shift in the overall approach to asthma management. The change in focus addresses the highly variable nature of asthma2 and the recognition that asthma severity and asthma control are distinct concepts serving different functions in clinical practice.

Severity and control in 2 domains. Asthma severity—a measure of the intrinsic intensity of the disease process—is ideally assessed before initiating treatment. In contrast, asthma control is monitored over time to guide adjustments to therapy. The guidelines call for assessing severity and control within the domains of:

- impairment, based on asthma symptoms (identified by patient or caregiver recall of the past 2-4 weeks), quality of life, and functional limitations; and

- risk, of asthma exacerbations, progressive decline in pulmonary function (or reduced lung growth in children), or adverse events. Predictors of increased risk for exacerbations or death include persistent and/or severe airflow obstruction; at least 2 visits to the emergency department or hospitalizations for asthma within the past year; and a history of intubation or admission to intensive care, especially within the past 5 years.

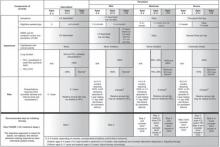

The specific criteria for determining asthma severity and assessing asthma control are detailed in FIGURES 1 AND 2, respectively. Because treatment affects impairment and risk differently, this dual assessment helps ensure that therapeutic interventions minimize all manifestations of asthma as much as possible.

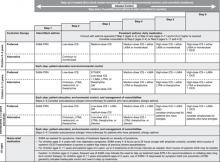

More steps and age-specific interventions. The EPR-3’s stepwise approach to asthma therapy has gone from 4 steps to 6, and the recommended treatments, as well as the levels of severity and criteria for assessing control that guide them, are now divided into 3 age groups: 0 to 4 years, 5 to 11 years, and ≥12 years (FIGURE 3). The previous guidelines, issued in 2002, divided treatment recommendations into 2 age groups: ≤5 years and >5 years. The EPR-3’s expansion makes it easier for physicians to initiate, individualize, and adjust treatment.

FIGURE 1

Classifying asthma severity and initiating therapy in children, adolescents, and adults

EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; NA, not applicable; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SABA, short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist.

*Normal FEV1/FVC values are defined according to age: 8–9 years (85%), 20–39 years (80%), 40–59 years (75%), 60–80 years (70%).

†For treatment purposes, children with at least 2 exacerbations (eg, requiring urgent, unscheduled care; hospitalization; or intensive care unit admission) or adolescents/adults with at least 2 exacerbations requiring OCS in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have persistent asthma, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with persistent asthma.

Adapted from: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).2

FIGURE 2

Assessing asthma control and adjusting therapy

ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire; ACT, Asthma Control Test; ATAQ, Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire; EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; N/A, not applicable; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SABA, short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist.

*ACQ values of 0.76 to 1.4 are indeterminate regarding well-controlled asthma.

†For treatment purposes, children with at least 2 exacerbations (eg, requiring urgent, unscheduled care; hospitalization; or intensive care unit admission) or adolescents/adults with at least 2 exacerbations requiring OCS in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have asthma that is not well controlled, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with that classification.

Adapted from: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).2

FIGURE 3

Stepwise approach for managing asthma

EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroid; PRN, as needed; SABA, short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist.

Adapted from: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).2

Putting guidelines into practice begins with the history

A detailed medical history and a physical examination focusing on the upper respiratory tract, chest, and skin are needed to arrive at an asthma diagnosis. JJ’s physician asked his mother to describe recent symptoms and inquired about comorbid conditions that can aggravate asthma. He also identified viral respiratory infections, environmental causes, and activity as precipitating factors.

In considering an asthma diagnosis, try to determine the presence of episodic symptoms of airflow obstruction or bronchial hyperresponsiveness, as well as airflow obstruction that is at least partly reversible (an increase in forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] of >200 mL and ≥12% from baseline or an increase of ≥10% of predicted FEV1), and to exclude alternative diagnoses.

EPR-3 emphasizes spirometry

Recognizing that patients’ perception of airflow obstruction is highly variable and that pulmonary function measures do not always correlate directly with symptoms,3,4 the EPR-3 recommends spirometry for patients ≥5 years of age, both before and after bronchodilation. In addition to helping to confirm an asthma diagnosis, spirometry is the preferred measure of pulmonary function in classifying severity, because peak expiratory flow (PEF) testing has not proven reliable.5,6

Objective measurement of pulmonary function is difficult to obtain in children <5 years of age. If diagnosis remains uncertain for patients in this age group, a therapeutic trial of medication is recommended. In JJ’s case, however, 3 courses of oral corticosteroids (OCS) in less than 6 months were indicative of persistent asthma.

Spirometry is often underutilized. For patients ≥5 years of age, spirometry is a vital tool, but often underutilized in family practice. A recent study by Yawn and colleagues found that family physicians made changes in the management of approximately half of the asthma patients who underwent spirometry.7 (Information about spirometry training is available through the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh.) Referral to a specialist is recommended if the physician has difficulty making a differential diagnosis or is unable to perform spirometry on a patient who presents with atypical signs and symptoms of asthma.

What is the patient’s level of severity?

In patients who are not yet receiving long-term controller therapy, severity level is based on an assessment of impairment and risk (FIGURE 1). For patients who are already receiving treatment, severity is determined by the minimum pharmacologic therapy needed to maintain asthma control.

The severity classification—intermittent asthma or persistent asthma that is mild, moderate, or severe—is determined by the most severe category in which any feature occurs. (In children, FEV1/FVC [forced vital capacity] ratio has been shown to be a more sensitive determinant of severity than FEV1,4 which may be more useful in predicting exacerbations.8)

Asthma management: Preferred and alternative Tx

The recommended stepwise interventions include both preferred therapies (evidence-based) and alternative treatments (listed alphabetically in FIGURE 3 because there is insufficient evidence to rank them). The additional steps and age categories support the goal of using the least possible medication needed to maintain good control and minimize the potential for adverse events.

In initiating treatment, select the step that corresponds to the level of severity in the bottom row of FIGURE 1; to adjust medications, determine the patient’s level of asthma control and follow the corresponding guidance in the bottom row of FIGURE 2.

Inhaled corticosteroids remain the bedrock of therapy

ICS, the most potent and consistently effective long-term controller therapy, remain the foundation of therapy for patients of all ages who have persistent asthma. (Evidence: A).

Several of the age-based recommendations follow, with a focus on preferred treatments:

Children 0 to 4 years of age

- The guidelines recommend low-dose ICS at Step 2 (Evidence: A) and medium-dose ICS at Step 3 (Evidence: D), as inhaled corticosteroids have been shown to reduce impairment and risk in this age group.9-16 The potential risk is generally limited to a small reduction in growth velocity during the first year of treatment, and offset by the benefits of therapy.15,16

- Add a long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist (LABA) or montelukast to medium-dose ICS therapy at Step 4 rather than increasing the ICS dose (Evidence: D) to avoid the risk of side effects associated with high-dose ICS. Montelukast has demonstrated efficacy in children 2 to 5 years of age with persistent asthma.17

- Recommendations for preferred therapy at Steps 5 (high-dose ICS + LABA or montelukast) and 6 (Step 5 therapy + OCS) are based on expert panel judgment (Evidence: D). When severe persistent asthma warrants Step 6 therapy, start with a 2-week course of the lowest possible dose of OCS to confirm reversibility.

- In this age group, a therapeutic trial with close monitoring is recommended for patients whose asthma is not well controlled. If there is no response in 4 to 6 weeks, consider alternative therapies or diagnoses (Evidence: D).

Children 5 to 11 years of age

- For Step 3 therapy, the guidelines recommend either low-dose ICS plus a LABA, leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), or theophylline; or medium-dose ICS (Evidence: B). Treatment decisions at Step 3 depend on whether impairment or risk is the chief concern, as well as on safety considerations.

- For Steps 4 and 5, ICS (medium dose for Step 5 and high dose for Step 6) plus a LABA is preferred, based on studies of patients ≥12 years of age (Evidence: B). Step 6 builds on Step 5, adding an OCS to the LABA/ICS combination (Evidence: D).

- If theophylline is prescribed—a viable option if cost and adherence to inhaled medications are key concerns—serum levels must be closely monitored because of the risk of toxicity.

- Closely monitor and be prepared to identify and respond to anaphylaxis in a child at Step 2, 3, or 4 who is receiving allergen immunotherapy.

Adolescents ≥12 years of age and adults

- There are 2 preferred Step 3 treatments: Low-dose ICS plus a LABA, or medium-dose ICS. The combination therapy has shown greater improvement in impairment24,25 and risk24-26 compared with the higher dose of ICS.

- Preferred treatments at Steps 4, 5, and 6 are the same as those for children ages 5 to 11 years, with one exception: Subcutaneous anti-IgE therapy (omalizumab) may be added to the regimen at Steps 5 and 6 for adolescents and adults with severe persistent allergic asthma to reduce the risk of exacerbations.27

Weigh the benefits and risks of therapy

Safety is a key consideration for all asthma patients. Carefully weigh the benefits and risks of therapy, including the rare but potential risk of life-threatening or fatal exacerbations with daily LABA therapy28 and systemic effects with higher doses of ICS.23 Patients who begin receiving oral corticosteroids require close monitoring, regardless of age.

Regular reassessment and monitoring are critical

Schedule visits at 2- to 6-week intervals for those who are starting therapy or require a step up to achieve or regain asthma control. After control is achieved, reassess at least every 1 to 6 months. Measures of asthma control are the same as those used to assess severity, with the addition of validated multidimensional questionnaires (eg, Asthma Control Test [ACT])29 to gauge impairment.

JJ’s physician scheduled a follow-up visit in 4 weeks, at which time he did a reassessment based on a physical exam and symptom recall. Finding JJ’s asthma to be well controlled, the physician asked the boy’s mother to bring him back to the office in 2 months, or earlier if symptoms recurred.

TABLE W1

Asthma education resources

| Allergy & Asthma Network Mothers of Asthmatics 2751 Prosperity Avenue, Suite 150 Fairfax, VA 22030 www.breatherville.org (800) 878-4403 or (703) 641-9595 | Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America 1233 20th Street, NW, Suite 402 Washington, DC 20036 www.aafa.org (800) 727-8462 |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 555 East Wells Street, Suite 1100 Milwaukee, WI 53202-3823 www.aaaai.org (414) 272-6071 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1600 Clifton Road Atlanta, GA 30333 www.cdc.gov (800) 311-3435 |

| American Association for Respiratory Care 9125 North macArthur boulevard, Suite 100 Irving, TX 75063 www.aarc.org (972) 243-2272 | Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network 11781 lee Jackson Highway, Suite 160 Fairfax, VA 22033 www.foodallergy.org (800) 929-4040 |

| American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 85 West Algonquin road, Suite 550 Arlington Heights, IL 60005 www.acaai.org (800) 842-7777 or (847) 427-1200 | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Information Center P.O. Box 30105 Bethesda, MD 20824-0105 www.nhlbi.nih.gov (301) 592-8573 |

| American Lung Association 61 Broadway New York, NY 10006 www.lungusa.org (800) 586-4872 | National Jewish Medical and Research Center (Lung Line) 1400 Jackson Street Denver, CO 80206 www.njc.org (800) 222-lUNG |

| Association of Asthma Educators 1215 Anthony Avenue Columbia, SC 29201 www.asthmaeducators.org (888) 988-7747 | US Environmental Protection Agency National Center for Environmental Publications P.O. Box 42419 Cincinnati, OH 45242-0419 www.airnow.gov (800) 490-9198 |

Does your patient require a step down or step up?

A step down is recommended for patients whose asthma is well controlled for 3 months or more. Reduce the dose of ICS gradually, about 25% to 50% every 3 months, because deterioration in asthma control is highly variable. Review adherence and medication administration technique with patients whose asthma is not well controlled, and consider a step up in treatment. If an alternative treatment is used but does not result in an adequate response, it should be discontinued and the preferred treatment used before stepping up. Refer patients to an asthma specialist if their asthma does not respond to these adjustments.

Partner with patients for optimal care

The EPR-3 recommends the integration of patient education into all aspects of asthma care. To forge an active partnership, identify and address concerns about the condition and its treatment and involve the patient and family in developing treatment goals and making treatment decisions. If the patient is old enough, encourage self-monitoring and management.

The EPR-3 recommends that physicians give every patient a written asthma action plan that addresses individual symptoms and/or PEF measurements and includes instructions for self-management. Daily PEF monitoring can be useful in identifying early changes in the disease state and evaluating response to changes in therapy. It is ideal for those who have moderate to severe persistent asthma, difficulty recognizing signs of exacerbations, or a history of severe exacerbations.

Correspondence

Stuart W. Stoloff, MD, Clinical Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Nevada–Reno, 1200 Mountain Street, Suite 220, Carson City, NV 89703; [email protected].

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Fast stats A to Z. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm. Accessed August 1, 2008.

2. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Full Report 2007. Bethesda, MD: NHLBI; August 2007. NIH publication no. 07-4051. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm. Accessed July 17, 2008.

3. Stout JW, Visness CM, Enright P, et al. Classification of asthma severity in children: the contribution of pulmonary function testing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:844-850.

4. Bacharier LB, Strunk RC, Mauger D, et al. Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:426-432.

5. Eid N, Yandell B, Howell L, Eddy M, Sheikh S. Can children with asthma? Pediatrics. 2000;105:354-358.

6. Llewellin P, Sawyer G, Lewis S, et al. The relationship between FEV1 and PEF in the assessment of the severity of airways obstruction. Respirology. 2002;7:333-337.

7. Yawn BP, Enright PL, Lemanske RF, Jr, et al. Spirometry can be done in family physicians’ offices and alters clinical decisions in management of asthma and COPD. Chest. 2007;132:1162-1168.

8. Fuhlbrigge AL, Kitch BT, Paltiel AD, et al. FEV1 is associated with risk of asthma attacks in a pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:61-67.

9. Roorda RJ, Mezei G, Bisgaard H, Maden C. Response of preschool children with asthma symptoms to fluticasone propionate. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:540-546.

10. Baker JW, Mellon M, Wald J, Welch M, Cruz-Rivera M, Walton-Bowen K. A multiple-dosing, placebo-controlled study of budesonide inhalation suspension given once or twice daily for treatment of persistent asthma in young children and infants. Pediatrics. 1999;103:414-421.

11. Kemp JP, Skoner DP, Szefler SJ, Walton-Bowen K, Cruz-Rivera M, Smith JA. Once-daily budesonide inhalation suspension for the treatment of persistent asthma in infants and young children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;83:231-239.

12. Shapiro G, Mendelson L, Kraemer MJ, Cruz-Rivera M, Walton-Bowen K, Smith JA. Efficacy and safety of budesonide inhalation suspension (Pulmicort Respules) in young children with inhaled steroid-dependent, persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:789-796.

13. Bisgaard H, Gillies J, Groenewald M, Maden C. The effect of inhaled fluticasone propionate in the treatment of young asthmatic children: a dose comparison study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:126-131.

14. Szefler SJ, Eigen H. Budesonide inhalation suspension: a nebulized corticosteroid for persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:730-742.

15. Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Zeiger RS, et al. Long-term inhaled corticosteroids in preschool children at high risk for asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1985-1997.

16. Bisgaard H, Allen D, Milanowski J, Kalev I, Willits L, Davies P. Twelve-month safety and efficacy of inhaled fluticasone propionate in children aged 1 to 3 years with recurrent wheezing. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e87-e94.

17. Knorr B, Franchi LM, Bisgaard H, et al. Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, for the treatment of persistent asthma in children aged 2 to 5 years. Pediatrics 2001;108:e48.-

18. Russell G, Williams DA, Weller P, Price JF. Salmeterol xinafoate in children on high dose inhaled steroids. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;75:423-428.

19. Zimmerman B, D’Urzo A, Bérubé D. Efficacy and safety of formoterol Turbuhaler when added to inhaled corticosteroid treatment in children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:122-127.

20. Simons FE, Villa JR, Lee BW, et al. Montelukast added to budesonide in children with persistent asthma: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J Pediatr. 2001;138:694-698.

21. Shapiro G, Bronsky EA, LaForce CF, et al. Dose-related efficacy of budesonide administered via a dry powder inhaler in the treatment of children with moderate to severe persistent asthma. J Pediatr. 1998;132:976-982.

22. Pauwels RA, Lofdahl C-G, Postma DS, et al. for the Formoterol and Corticosteroids Establishing Therapy (FACET) International Study Group. Effect of inhaled formoterol and budesonide on exacerbations of asthma. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1405-1411.

23. Tattersfield AE, Harrison TW, Hubbard RB, Mortimer K. Safety of inhaled corticosteroids. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:171-175.

24. Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. For the GOAL Investigators Group. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:836-844.

25. O’Byrne PM, Barnes PJ, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Low dose inhaled budesonide and formoterol in mild persistent asthma: the OPTIMA randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1392-1397.

26. Masoli M, Weatherall M, Holt S, Beasley R. Moderate dose inhaled corticosteroids plus salmeterol versus higher doses of inhaled corticosteroids in symptomatic asthma. Thorax. 2005;60:730-734.

27. Bousquet J, Wenzel S, Holgate S, Lumry W, Freeman P, Fox H. Predicting response to omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, in patients with allergic asthma. Chest. 2004;125:1378-1386.

28. Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, Yancey SW, Dorinsky PM. For the SMART Study Group. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest. 2006;129:15-26.

29. Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:59-65.

- Assess asthma severity before initiating treatment; monitor asthma control to guide adjustments in therapy using measures of impairment (B) and risk (C) (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI] and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program [NAEPP] third expert panel report [EPR-3]).

- Base treatment decisions on recommendations specific to each age group (0-4 years, 5-11 years, and ≥12 years) (A).

- Use spirometry in patients ≥5 years of age to diagnose asthma, classify severity, and assess control (C).

- Provide each patient with a written asthma action plan with instructions for daily disease management, as well as identification of, and response to, worsening symptoms (B).

EPR-3 evidence categories:

- Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs), rich body of data

- RCTs, limited body of data

- Nonrandomized trials and observational studies

- Panel consensus judgment

JJ, a 4-year-old boy, was taken to an urgent care clinic 3 times last winter for “recurrent bronchitis” and given a 7-day course of prednisone and antibiotics at each visit. His mother reports that “his colds always seem to go to his chest” and his skin is always dry. She was given a nebulizer and albuterol for use when JJ begins wheezing, which often happens when he has a cold, plays vigorously, or visits a friend who has cats.

JJ is one of approximately 6.7 million children—and 22.9 million US residents—who have asthma.1 To help guide the care of patients like JJ, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) released the third expert panel report (EPR-3) in 2007. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm, the EPR-3 provides the most comprehensive evidence-based guidance for the diagnosis and management of asthma to date.2

The guidelines were an invaluable resource for JJ’s family physician, who referred to them to categorize the severity of JJ’s asthma as “mild persistent.” In initiating treatment, JJ’s physician relied on specific recommendations for children 0 to 4 years of age to prescribe low-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). Without the new guidelines, which underscore the safety of controller medication for young children, JJ’s physician would likely have been reluctant to place a 4-year-old on ICS.

This review highlights the EPR-3’s key recommendations to encourage widespread implementation by family physicians.

The EPR-3: What’s changed

The 2007 guidelines:

Recommend assessing asthma severity before starting treatment and assessing asthma control to guide adjustments in treatment.

Address both severity and control in terms of impairment and risk.

Feature 3 age breakdowns (0-4 years, 5-11 years, and ≥12 years) and a 6-step approach to asthma management.

Make it easier to individualize and adjust treatment.

What’s changed?

There’s a new paradigm

The 2007 update to guidelines released in 1997 and 2002 reflects a paradigm shift in the overall approach to asthma management. The change in focus addresses the highly variable nature of asthma2 and the recognition that asthma severity and asthma control are distinct concepts serving different functions in clinical practice.

Severity and control in 2 domains. Asthma severity—a measure of the intrinsic intensity of the disease process—is ideally assessed before initiating treatment. In contrast, asthma control is monitored over time to guide adjustments to therapy. The guidelines call for assessing severity and control within the domains of:

- impairment, based on asthma symptoms (identified by patient or caregiver recall of the past 2-4 weeks), quality of life, and functional limitations; and

- risk, of asthma exacerbations, progressive decline in pulmonary function (or reduced lung growth in children), or adverse events. Predictors of increased risk for exacerbations or death include persistent and/or severe airflow obstruction; at least 2 visits to the emergency department or hospitalizations for asthma within the past year; and a history of intubation or admission to intensive care, especially within the past 5 years.

The specific criteria for determining asthma severity and assessing asthma control are detailed in FIGURES 1 AND 2, respectively. Because treatment affects impairment and risk differently, this dual assessment helps ensure that therapeutic interventions minimize all manifestations of asthma as much as possible.

More steps and age-specific interventions. The EPR-3’s stepwise approach to asthma therapy has gone from 4 steps to 6, and the recommended treatments, as well as the levels of severity and criteria for assessing control that guide them, are now divided into 3 age groups: 0 to 4 years, 5 to 11 years, and ≥12 years (FIGURE 3). The previous guidelines, issued in 2002, divided treatment recommendations into 2 age groups: ≤5 years and >5 years. The EPR-3’s expansion makes it easier for physicians to initiate, individualize, and adjust treatment.

FIGURE 1

Classifying asthma severity and initiating therapy in children, adolescents, and adults

EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; NA, not applicable; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SABA, short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist.

*Normal FEV1/FVC values are defined according to age: 8–9 years (85%), 20–39 years (80%), 40–59 years (75%), 60–80 years (70%).

†For treatment purposes, children with at least 2 exacerbations (eg, requiring urgent, unscheduled care; hospitalization; or intensive care unit admission) or adolescents/adults with at least 2 exacerbations requiring OCS in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have persistent asthma, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with persistent asthma.

Adapted from: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).2

FIGURE 2

Assessing asthma control and adjusting therapy

ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire; ACT, Asthma Control Test; ATAQ, Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire; EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; N/A, not applicable; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SABA, short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist.

*ACQ values of 0.76 to 1.4 are indeterminate regarding well-controlled asthma.

†For treatment purposes, children with at least 2 exacerbations (eg, requiring urgent, unscheduled care; hospitalization; or intensive care unit admission) or adolescents/adults with at least 2 exacerbations requiring OCS in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have asthma that is not well controlled, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with that classification.

Adapted from: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).2

FIGURE 3

Stepwise approach for managing asthma

EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroid; PRN, as needed; SABA, short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist.

Adapted from: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).2

Putting guidelines into practice begins with the history

A detailed medical history and a physical examination focusing on the upper respiratory tract, chest, and skin are needed to arrive at an asthma diagnosis. JJ’s physician asked his mother to describe recent symptoms and inquired about comorbid conditions that can aggravate asthma. He also identified viral respiratory infections, environmental causes, and activity as precipitating factors.

In considering an asthma diagnosis, try to determine the presence of episodic symptoms of airflow obstruction or bronchial hyperresponsiveness, as well as airflow obstruction that is at least partly reversible (an increase in forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] of >200 mL and ≥12% from baseline or an increase of ≥10% of predicted FEV1), and to exclude alternative diagnoses.

EPR-3 emphasizes spirometry

Recognizing that patients’ perception of airflow obstruction is highly variable and that pulmonary function measures do not always correlate directly with symptoms,3,4 the EPR-3 recommends spirometry for patients ≥5 years of age, both before and after bronchodilation. In addition to helping to confirm an asthma diagnosis, spirometry is the preferred measure of pulmonary function in classifying severity, because peak expiratory flow (PEF) testing has not proven reliable.5,6

Objective measurement of pulmonary function is difficult to obtain in children <5 years of age. If diagnosis remains uncertain for patients in this age group, a therapeutic trial of medication is recommended. In JJ’s case, however, 3 courses of oral corticosteroids (OCS) in less than 6 months were indicative of persistent asthma.

Spirometry is often underutilized. For patients ≥5 years of age, spirometry is a vital tool, but often underutilized in family practice. A recent study by Yawn and colleagues found that family physicians made changes in the management of approximately half of the asthma patients who underwent spirometry.7 (Information about spirometry training is available through the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh.) Referral to a specialist is recommended if the physician has difficulty making a differential diagnosis or is unable to perform spirometry on a patient who presents with atypical signs and symptoms of asthma.

What is the patient’s level of severity?

In patients who are not yet receiving long-term controller therapy, severity level is based on an assessment of impairment and risk (FIGURE 1). For patients who are already receiving treatment, severity is determined by the minimum pharmacologic therapy needed to maintain asthma control.

The severity classification—intermittent asthma or persistent asthma that is mild, moderate, or severe—is determined by the most severe category in which any feature occurs. (In children, FEV1/FVC [forced vital capacity] ratio has been shown to be a more sensitive determinant of severity than FEV1,4 which may be more useful in predicting exacerbations.8)

Asthma management: Preferred and alternative Tx

The recommended stepwise interventions include both preferred therapies (evidence-based) and alternative treatments (listed alphabetically in FIGURE 3 because there is insufficient evidence to rank them). The additional steps and age categories support the goal of using the least possible medication needed to maintain good control and minimize the potential for adverse events.

In initiating treatment, select the step that corresponds to the level of severity in the bottom row of FIGURE 1; to adjust medications, determine the patient’s level of asthma control and follow the corresponding guidance in the bottom row of FIGURE 2.

Inhaled corticosteroids remain the bedrock of therapy

ICS, the most potent and consistently effective long-term controller therapy, remain the foundation of therapy for patients of all ages who have persistent asthma. (Evidence: A).

Several of the age-based recommendations follow, with a focus on preferred treatments:

Children 0 to 4 years of age

- The guidelines recommend low-dose ICS at Step 2 (Evidence: A) and medium-dose ICS at Step 3 (Evidence: D), as inhaled corticosteroids have been shown to reduce impairment and risk in this age group.9-16 The potential risk is generally limited to a small reduction in growth velocity during the first year of treatment, and offset by the benefits of therapy.15,16

- Add a long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist (LABA) or montelukast to medium-dose ICS therapy at Step 4 rather than increasing the ICS dose (Evidence: D) to avoid the risk of side effects associated with high-dose ICS. Montelukast has demonstrated efficacy in children 2 to 5 years of age with persistent asthma.17

- Recommendations for preferred therapy at Steps 5 (high-dose ICS + LABA or montelukast) and 6 (Step 5 therapy + OCS) are based on expert panel judgment (Evidence: D). When severe persistent asthma warrants Step 6 therapy, start with a 2-week course of the lowest possible dose of OCS to confirm reversibility.

- In this age group, a therapeutic trial with close monitoring is recommended for patients whose asthma is not well controlled. If there is no response in 4 to 6 weeks, consider alternative therapies or diagnoses (Evidence: D).

Children 5 to 11 years of age

- For Step 3 therapy, the guidelines recommend either low-dose ICS plus a LABA, leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), or theophylline; or medium-dose ICS (Evidence: B). Treatment decisions at Step 3 depend on whether impairment or risk is the chief concern, as well as on safety considerations.

- For Steps 4 and 5, ICS (medium dose for Step 5 and high dose for Step 6) plus a LABA is preferred, based on studies of patients ≥12 years of age (Evidence: B). Step 6 builds on Step 5, adding an OCS to the LABA/ICS combination (Evidence: D).

- If theophylline is prescribed—a viable option if cost and adherence to inhaled medications are key concerns—serum levels must be closely monitored because of the risk of toxicity.

- Closely monitor and be prepared to identify and respond to anaphylaxis in a child at Step 2, 3, or 4 who is receiving allergen immunotherapy.

Adolescents ≥12 years of age and adults

- There are 2 preferred Step 3 treatments: Low-dose ICS plus a LABA, or medium-dose ICS. The combination therapy has shown greater improvement in impairment24,25 and risk24-26 compared with the higher dose of ICS.

- Preferred treatments at Steps 4, 5, and 6 are the same as those for children ages 5 to 11 years, with one exception: Subcutaneous anti-IgE therapy (omalizumab) may be added to the regimen at Steps 5 and 6 for adolescents and adults with severe persistent allergic asthma to reduce the risk of exacerbations.27

Weigh the benefits and risks of therapy

Safety is a key consideration for all asthma patients. Carefully weigh the benefits and risks of therapy, including the rare but potential risk of life-threatening or fatal exacerbations with daily LABA therapy28 and systemic effects with higher doses of ICS.23 Patients who begin receiving oral corticosteroids require close monitoring, regardless of age.

Regular reassessment and monitoring are critical

Schedule visits at 2- to 6-week intervals for those who are starting therapy or require a step up to achieve or regain asthma control. After control is achieved, reassess at least every 1 to 6 months. Measures of asthma control are the same as those used to assess severity, with the addition of validated multidimensional questionnaires (eg, Asthma Control Test [ACT])29 to gauge impairment.

JJ’s physician scheduled a follow-up visit in 4 weeks, at which time he did a reassessment based on a physical exam and symptom recall. Finding JJ’s asthma to be well controlled, the physician asked the boy’s mother to bring him back to the office in 2 months, or earlier if symptoms recurred.

TABLE W1

Asthma education resources

| Allergy & Asthma Network Mothers of Asthmatics 2751 Prosperity Avenue, Suite 150 Fairfax, VA 22030 www.breatherville.org (800) 878-4403 or (703) 641-9595 | Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America 1233 20th Street, NW, Suite 402 Washington, DC 20036 www.aafa.org (800) 727-8462 |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 555 East Wells Street, Suite 1100 Milwaukee, WI 53202-3823 www.aaaai.org (414) 272-6071 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1600 Clifton Road Atlanta, GA 30333 www.cdc.gov (800) 311-3435 |

| American Association for Respiratory Care 9125 North macArthur boulevard, Suite 100 Irving, TX 75063 www.aarc.org (972) 243-2272 | Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network 11781 lee Jackson Highway, Suite 160 Fairfax, VA 22033 www.foodallergy.org (800) 929-4040 |

| American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 85 West Algonquin road, Suite 550 Arlington Heights, IL 60005 www.acaai.org (800) 842-7777 or (847) 427-1200 | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Information Center P.O. Box 30105 Bethesda, MD 20824-0105 www.nhlbi.nih.gov (301) 592-8573 |

| American Lung Association 61 Broadway New York, NY 10006 www.lungusa.org (800) 586-4872 | National Jewish Medical and Research Center (Lung Line) 1400 Jackson Street Denver, CO 80206 www.njc.org (800) 222-lUNG |

| Association of Asthma Educators 1215 Anthony Avenue Columbia, SC 29201 www.asthmaeducators.org (888) 988-7747 | US Environmental Protection Agency National Center for Environmental Publications P.O. Box 42419 Cincinnati, OH 45242-0419 www.airnow.gov (800) 490-9198 |

Does your patient require a step down or step up?

A step down is recommended for patients whose asthma is well controlled for 3 months or more. Reduce the dose of ICS gradually, about 25% to 50% every 3 months, because deterioration in asthma control is highly variable. Review adherence and medication administration technique with patients whose asthma is not well controlled, and consider a step up in treatment. If an alternative treatment is used but does not result in an adequate response, it should be discontinued and the preferred treatment used before stepping up. Refer patients to an asthma specialist if their asthma does not respond to these adjustments.

Partner with patients for optimal care

The EPR-3 recommends the integration of patient education into all aspects of asthma care. To forge an active partnership, identify and address concerns about the condition and its treatment and involve the patient and family in developing treatment goals and making treatment decisions. If the patient is old enough, encourage self-monitoring and management.

The EPR-3 recommends that physicians give every patient a written asthma action plan that addresses individual symptoms and/or PEF measurements and includes instructions for self-management. Daily PEF monitoring can be useful in identifying early changes in the disease state and evaluating response to changes in therapy. It is ideal for those who have moderate to severe persistent asthma, difficulty recognizing signs of exacerbations, or a history of severe exacerbations.

Correspondence

Stuart W. Stoloff, MD, Clinical Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Nevada–Reno, 1200 Mountain Street, Suite 220, Carson City, NV 89703; [email protected].

- Assess asthma severity before initiating treatment; monitor asthma control to guide adjustments in therapy using measures of impairment (B) and risk (C) (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI] and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program [NAEPP] third expert panel report [EPR-3]).

- Base treatment decisions on recommendations specific to each age group (0-4 years, 5-11 years, and ≥12 years) (A).

- Use spirometry in patients ≥5 years of age to diagnose asthma, classify severity, and assess control (C).

- Provide each patient with a written asthma action plan with instructions for daily disease management, as well as identification of, and response to, worsening symptoms (B).

EPR-3 evidence categories:

- Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs), rich body of data

- RCTs, limited body of data

- Nonrandomized trials and observational studies

- Panel consensus judgment

JJ, a 4-year-old boy, was taken to an urgent care clinic 3 times last winter for “recurrent bronchitis” and given a 7-day course of prednisone and antibiotics at each visit. His mother reports that “his colds always seem to go to his chest” and his skin is always dry. She was given a nebulizer and albuterol for use when JJ begins wheezing, which often happens when he has a cold, plays vigorously, or visits a friend who has cats.

JJ is one of approximately 6.7 million children—and 22.9 million US residents—who have asthma.1 To help guide the care of patients like JJ, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) released the third expert panel report (EPR-3) in 2007. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm, the EPR-3 provides the most comprehensive evidence-based guidance for the diagnosis and management of asthma to date.2

The guidelines were an invaluable resource for JJ’s family physician, who referred to them to categorize the severity of JJ’s asthma as “mild persistent.” In initiating treatment, JJ’s physician relied on specific recommendations for children 0 to 4 years of age to prescribe low-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). Without the new guidelines, which underscore the safety of controller medication for young children, JJ’s physician would likely have been reluctant to place a 4-year-old on ICS.

This review highlights the EPR-3’s key recommendations to encourage widespread implementation by family physicians.

The EPR-3: What’s changed

The 2007 guidelines:

Recommend assessing asthma severity before starting treatment and assessing asthma control to guide adjustments in treatment.

Address both severity and control in terms of impairment and risk.

Feature 3 age breakdowns (0-4 years, 5-11 years, and ≥12 years) and a 6-step approach to asthma management.

Make it easier to individualize and adjust treatment.

What’s changed?

There’s a new paradigm

The 2007 update to guidelines released in 1997 and 2002 reflects a paradigm shift in the overall approach to asthma management. The change in focus addresses the highly variable nature of asthma2 and the recognition that asthma severity and asthma control are distinct concepts serving different functions in clinical practice.

Severity and control in 2 domains. Asthma severity—a measure of the intrinsic intensity of the disease process—is ideally assessed before initiating treatment. In contrast, asthma control is monitored over time to guide adjustments to therapy. The guidelines call for assessing severity and control within the domains of:

- impairment, based on asthma symptoms (identified by patient or caregiver recall of the past 2-4 weeks), quality of life, and functional limitations; and

- risk, of asthma exacerbations, progressive decline in pulmonary function (or reduced lung growth in children), or adverse events. Predictors of increased risk for exacerbations or death include persistent and/or severe airflow obstruction; at least 2 visits to the emergency department or hospitalizations for asthma within the past year; and a history of intubation or admission to intensive care, especially within the past 5 years.

The specific criteria for determining asthma severity and assessing asthma control are detailed in FIGURES 1 AND 2, respectively. Because treatment affects impairment and risk differently, this dual assessment helps ensure that therapeutic interventions minimize all manifestations of asthma as much as possible.

More steps and age-specific interventions. The EPR-3’s stepwise approach to asthma therapy has gone from 4 steps to 6, and the recommended treatments, as well as the levels of severity and criteria for assessing control that guide them, are now divided into 3 age groups: 0 to 4 years, 5 to 11 years, and ≥12 years (FIGURE 3). The previous guidelines, issued in 2002, divided treatment recommendations into 2 age groups: ≤5 years and >5 years. The EPR-3’s expansion makes it easier for physicians to initiate, individualize, and adjust treatment.

FIGURE 1

Classifying asthma severity and initiating therapy in children, adolescents, and adults

EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; NA, not applicable; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SABA, short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist.

*Normal FEV1/FVC values are defined according to age: 8–9 years (85%), 20–39 years (80%), 40–59 years (75%), 60–80 years (70%).

†For treatment purposes, children with at least 2 exacerbations (eg, requiring urgent, unscheduled care; hospitalization; or intensive care unit admission) or adolescents/adults with at least 2 exacerbations requiring OCS in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have persistent asthma, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with persistent asthma.

Adapted from: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).2

FIGURE 2

Assessing asthma control and adjusting therapy

ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire; ACT, Asthma Control Test; ATAQ, Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire; EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; N/A, not applicable; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SABA, short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist.

*ACQ values of 0.76 to 1.4 are indeterminate regarding well-controlled asthma.

†For treatment purposes, children with at least 2 exacerbations (eg, requiring urgent, unscheduled care; hospitalization; or intensive care unit admission) or adolescents/adults with at least 2 exacerbations requiring OCS in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have asthma that is not well controlled, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with that classification.

Adapted from: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).2

FIGURE 3

Stepwise approach for managing asthma

EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroid; PRN, as needed; SABA, short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist.

Adapted from: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).2

Putting guidelines into practice begins with the history

A detailed medical history and a physical examination focusing on the upper respiratory tract, chest, and skin are needed to arrive at an asthma diagnosis. JJ’s physician asked his mother to describe recent symptoms and inquired about comorbid conditions that can aggravate asthma. He also identified viral respiratory infections, environmental causes, and activity as precipitating factors.

In considering an asthma diagnosis, try to determine the presence of episodic symptoms of airflow obstruction or bronchial hyperresponsiveness, as well as airflow obstruction that is at least partly reversible (an increase in forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] of >200 mL and ≥12% from baseline or an increase of ≥10% of predicted FEV1), and to exclude alternative diagnoses.

EPR-3 emphasizes spirometry

Recognizing that patients’ perception of airflow obstruction is highly variable and that pulmonary function measures do not always correlate directly with symptoms,3,4 the EPR-3 recommends spirometry for patients ≥5 years of age, both before and after bronchodilation. In addition to helping to confirm an asthma diagnosis, spirometry is the preferred measure of pulmonary function in classifying severity, because peak expiratory flow (PEF) testing has not proven reliable.5,6

Objective measurement of pulmonary function is difficult to obtain in children <5 years of age. If diagnosis remains uncertain for patients in this age group, a therapeutic trial of medication is recommended. In JJ’s case, however, 3 courses of oral corticosteroids (OCS) in less than 6 months were indicative of persistent asthma.

Spirometry is often underutilized. For patients ≥5 years of age, spirometry is a vital tool, but often underutilized in family practice. A recent study by Yawn and colleagues found that family physicians made changes in the management of approximately half of the asthma patients who underwent spirometry.7 (Information about spirometry training is available through the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh.) Referral to a specialist is recommended if the physician has difficulty making a differential diagnosis or is unable to perform spirometry on a patient who presents with atypical signs and symptoms of asthma.

What is the patient’s level of severity?

In patients who are not yet receiving long-term controller therapy, severity level is based on an assessment of impairment and risk (FIGURE 1). For patients who are already receiving treatment, severity is determined by the minimum pharmacologic therapy needed to maintain asthma control.

The severity classification—intermittent asthma or persistent asthma that is mild, moderate, or severe—is determined by the most severe category in which any feature occurs. (In children, FEV1/FVC [forced vital capacity] ratio has been shown to be a more sensitive determinant of severity than FEV1,4 which may be more useful in predicting exacerbations.8)

Asthma management: Preferred and alternative Tx

The recommended stepwise interventions include both preferred therapies (evidence-based) and alternative treatments (listed alphabetically in FIGURE 3 because there is insufficient evidence to rank them). The additional steps and age categories support the goal of using the least possible medication needed to maintain good control and minimize the potential for adverse events.

In initiating treatment, select the step that corresponds to the level of severity in the bottom row of FIGURE 1; to adjust medications, determine the patient’s level of asthma control and follow the corresponding guidance in the bottom row of FIGURE 2.

Inhaled corticosteroids remain the bedrock of therapy

ICS, the most potent and consistently effective long-term controller therapy, remain the foundation of therapy for patients of all ages who have persistent asthma. (Evidence: A).

Several of the age-based recommendations follow, with a focus on preferred treatments:

Children 0 to 4 years of age

- The guidelines recommend low-dose ICS at Step 2 (Evidence: A) and medium-dose ICS at Step 3 (Evidence: D), as inhaled corticosteroids have been shown to reduce impairment and risk in this age group.9-16 The potential risk is generally limited to a small reduction in growth velocity during the first year of treatment, and offset by the benefits of therapy.15,16

- Add a long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist (LABA) or montelukast to medium-dose ICS therapy at Step 4 rather than increasing the ICS dose (Evidence: D) to avoid the risk of side effects associated with high-dose ICS. Montelukast has demonstrated efficacy in children 2 to 5 years of age with persistent asthma.17

- Recommendations for preferred therapy at Steps 5 (high-dose ICS + LABA or montelukast) and 6 (Step 5 therapy + OCS) are based on expert panel judgment (Evidence: D). When severe persistent asthma warrants Step 6 therapy, start with a 2-week course of the lowest possible dose of OCS to confirm reversibility.

- In this age group, a therapeutic trial with close monitoring is recommended for patients whose asthma is not well controlled. If there is no response in 4 to 6 weeks, consider alternative therapies or diagnoses (Evidence: D).

Children 5 to 11 years of age

- For Step 3 therapy, the guidelines recommend either low-dose ICS plus a LABA, leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), or theophylline; or medium-dose ICS (Evidence: B). Treatment decisions at Step 3 depend on whether impairment or risk is the chief concern, as well as on safety considerations.

- For Steps 4 and 5, ICS (medium dose for Step 5 and high dose for Step 6) plus a LABA is preferred, based on studies of patients ≥12 years of age (Evidence: B). Step 6 builds on Step 5, adding an OCS to the LABA/ICS combination (Evidence: D).

- If theophylline is prescribed—a viable option if cost and adherence to inhaled medications are key concerns—serum levels must be closely monitored because of the risk of toxicity.

- Closely monitor and be prepared to identify and respond to anaphylaxis in a child at Step 2, 3, or 4 who is receiving allergen immunotherapy.

Adolescents ≥12 years of age and adults

- There are 2 preferred Step 3 treatments: Low-dose ICS plus a LABA, or medium-dose ICS. The combination therapy has shown greater improvement in impairment24,25 and risk24-26 compared with the higher dose of ICS.

- Preferred treatments at Steps 4, 5, and 6 are the same as those for children ages 5 to 11 years, with one exception: Subcutaneous anti-IgE therapy (omalizumab) may be added to the regimen at Steps 5 and 6 for adolescents and adults with severe persistent allergic asthma to reduce the risk of exacerbations.27

Weigh the benefits and risks of therapy

Safety is a key consideration for all asthma patients. Carefully weigh the benefits and risks of therapy, including the rare but potential risk of life-threatening or fatal exacerbations with daily LABA therapy28 and systemic effects with higher doses of ICS.23 Patients who begin receiving oral corticosteroids require close monitoring, regardless of age.

Regular reassessment and monitoring are critical

Schedule visits at 2- to 6-week intervals for those who are starting therapy or require a step up to achieve or regain asthma control. After control is achieved, reassess at least every 1 to 6 months. Measures of asthma control are the same as those used to assess severity, with the addition of validated multidimensional questionnaires (eg, Asthma Control Test [ACT])29 to gauge impairment.

JJ’s physician scheduled a follow-up visit in 4 weeks, at which time he did a reassessment based on a physical exam and symptom recall. Finding JJ’s asthma to be well controlled, the physician asked the boy’s mother to bring him back to the office in 2 months, or earlier if symptoms recurred.

TABLE W1

Asthma education resources

| Allergy & Asthma Network Mothers of Asthmatics 2751 Prosperity Avenue, Suite 150 Fairfax, VA 22030 www.breatherville.org (800) 878-4403 or (703) 641-9595 | Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America 1233 20th Street, NW, Suite 402 Washington, DC 20036 www.aafa.org (800) 727-8462 |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 555 East Wells Street, Suite 1100 Milwaukee, WI 53202-3823 www.aaaai.org (414) 272-6071 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1600 Clifton Road Atlanta, GA 30333 www.cdc.gov (800) 311-3435 |

| American Association for Respiratory Care 9125 North macArthur boulevard, Suite 100 Irving, TX 75063 www.aarc.org (972) 243-2272 | Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network 11781 lee Jackson Highway, Suite 160 Fairfax, VA 22033 www.foodallergy.org (800) 929-4040 |

| American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 85 West Algonquin road, Suite 550 Arlington Heights, IL 60005 www.acaai.org (800) 842-7777 or (847) 427-1200 | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Information Center P.O. Box 30105 Bethesda, MD 20824-0105 www.nhlbi.nih.gov (301) 592-8573 |

| American Lung Association 61 Broadway New York, NY 10006 www.lungusa.org (800) 586-4872 | National Jewish Medical and Research Center (Lung Line) 1400 Jackson Street Denver, CO 80206 www.njc.org (800) 222-lUNG |

| Association of Asthma Educators 1215 Anthony Avenue Columbia, SC 29201 www.asthmaeducators.org (888) 988-7747 | US Environmental Protection Agency National Center for Environmental Publications P.O. Box 42419 Cincinnati, OH 45242-0419 www.airnow.gov (800) 490-9198 |

Does your patient require a step down or step up?

A step down is recommended for patients whose asthma is well controlled for 3 months or more. Reduce the dose of ICS gradually, about 25% to 50% every 3 months, because deterioration in asthma control is highly variable. Review adherence and medication administration technique with patients whose asthma is not well controlled, and consider a step up in treatment. If an alternative treatment is used but does not result in an adequate response, it should be discontinued and the preferred treatment used before stepping up. Refer patients to an asthma specialist if their asthma does not respond to these adjustments.

Partner with patients for optimal care

The EPR-3 recommends the integration of patient education into all aspects of asthma care. To forge an active partnership, identify and address concerns about the condition and its treatment and involve the patient and family in developing treatment goals and making treatment decisions. If the patient is old enough, encourage self-monitoring and management.

The EPR-3 recommends that physicians give every patient a written asthma action plan that addresses individual symptoms and/or PEF measurements and includes instructions for self-management. Daily PEF monitoring can be useful in identifying early changes in the disease state and evaluating response to changes in therapy. It is ideal for those who have moderate to severe persistent asthma, difficulty recognizing signs of exacerbations, or a history of severe exacerbations.

Correspondence

Stuart W. Stoloff, MD, Clinical Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Nevada–Reno, 1200 Mountain Street, Suite 220, Carson City, NV 89703; [email protected].

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Fast stats A to Z. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm. Accessed August 1, 2008.

2. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Full Report 2007. Bethesda, MD: NHLBI; August 2007. NIH publication no. 07-4051. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm. Accessed July 17, 2008.

3. Stout JW, Visness CM, Enright P, et al. Classification of asthma severity in children: the contribution of pulmonary function testing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:844-850.

4. Bacharier LB, Strunk RC, Mauger D, et al. Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:426-432.

5. Eid N, Yandell B, Howell L, Eddy M, Sheikh S. Can children with asthma? Pediatrics. 2000;105:354-358.

6. Llewellin P, Sawyer G, Lewis S, et al. The relationship between FEV1 and PEF in the assessment of the severity of airways obstruction. Respirology. 2002;7:333-337.

7. Yawn BP, Enright PL, Lemanske RF, Jr, et al. Spirometry can be done in family physicians’ offices and alters clinical decisions in management of asthma and COPD. Chest. 2007;132:1162-1168.

8. Fuhlbrigge AL, Kitch BT, Paltiel AD, et al. FEV1 is associated with risk of asthma attacks in a pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:61-67.

9. Roorda RJ, Mezei G, Bisgaard H, Maden C. Response of preschool children with asthma symptoms to fluticasone propionate. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:540-546.

10. Baker JW, Mellon M, Wald J, Welch M, Cruz-Rivera M, Walton-Bowen K. A multiple-dosing, placebo-controlled study of budesonide inhalation suspension given once or twice daily for treatment of persistent asthma in young children and infants. Pediatrics. 1999;103:414-421.

11. Kemp JP, Skoner DP, Szefler SJ, Walton-Bowen K, Cruz-Rivera M, Smith JA. Once-daily budesonide inhalation suspension for the treatment of persistent asthma in infants and young children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;83:231-239.

12. Shapiro G, Mendelson L, Kraemer MJ, Cruz-Rivera M, Walton-Bowen K, Smith JA. Efficacy and safety of budesonide inhalation suspension (Pulmicort Respules) in young children with inhaled steroid-dependent, persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:789-796.

13. Bisgaard H, Gillies J, Groenewald M, Maden C. The effect of inhaled fluticasone propionate in the treatment of young asthmatic children: a dose comparison study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:126-131.

14. Szefler SJ, Eigen H. Budesonide inhalation suspension: a nebulized corticosteroid for persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:730-742.

15. Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Zeiger RS, et al. Long-term inhaled corticosteroids in preschool children at high risk for asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1985-1997.

16. Bisgaard H, Allen D, Milanowski J, Kalev I, Willits L, Davies P. Twelve-month safety and efficacy of inhaled fluticasone propionate in children aged 1 to 3 years with recurrent wheezing. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e87-e94.

17. Knorr B, Franchi LM, Bisgaard H, et al. Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, for the treatment of persistent asthma in children aged 2 to 5 years. Pediatrics 2001;108:e48.-

18. Russell G, Williams DA, Weller P, Price JF. Salmeterol xinafoate in children on high dose inhaled steroids. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;75:423-428.

19. Zimmerman B, D’Urzo A, Bérubé D. Efficacy and safety of formoterol Turbuhaler when added to inhaled corticosteroid treatment in children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:122-127.

20. Simons FE, Villa JR, Lee BW, et al. Montelukast added to budesonide in children with persistent asthma: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J Pediatr. 2001;138:694-698.

21. Shapiro G, Bronsky EA, LaForce CF, et al. Dose-related efficacy of budesonide administered via a dry powder inhaler in the treatment of children with moderate to severe persistent asthma. J Pediatr. 1998;132:976-982.

22. Pauwels RA, Lofdahl C-G, Postma DS, et al. for the Formoterol and Corticosteroids Establishing Therapy (FACET) International Study Group. Effect of inhaled formoterol and budesonide on exacerbations of asthma. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1405-1411.

23. Tattersfield AE, Harrison TW, Hubbard RB, Mortimer K. Safety of inhaled corticosteroids. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:171-175.

24. Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. For the GOAL Investigators Group. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:836-844.

25. O’Byrne PM, Barnes PJ, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Low dose inhaled budesonide and formoterol in mild persistent asthma: the OPTIMA randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1392-1397.

26. Masoli M, Weatherall M, Holt S, Beasley R. Moderate dose inhaled corticosteroids plus salmeterol versus higher doses of inhaled corticosteroids in symptomatic asthma. Thorax. 2005;60:730-734.

27. Bousquet J, Wenzel S, Holgate S, Lumry W, Freeman P, Fox H. Predicting response to omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, in patients with allergic asthma. Chest. 2004;125:1378-1386.

28. Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, Yancey SW, Dorinsky PM. For the SMART Study Group. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest. 2006;129:15-26.

29. Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:59-65.

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Fast stats A to Z. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm. Accessed August 1, 2008.

2. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Full Report 2007. Bethesda, MD: NHLBI; August 2007. NIH publication no. 07-4051. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm. Accessed July 17, 2008.

3. Stout JW, Visness CM, Enright P, et al. Classification of asthma severity in children: the contribution of pulmonary function testing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:844-850.

4. Bacharier LB, Strunk RC, Mauger D, et al. Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:426-432.

5. Eid N, Yandell B, Howell L, Eddy M, Sheikh S. Can children with asthma? Pediatrics. 2000;105:354-358.

6. Llewellin P, Sawyer G, Lewis S, et al. The relationship between FEV1 and PEF in the assessment of the severity of airways obstruction. Respirology. 2002;7:333-337.

7. Yawn BP, Enright PL, Lemanske RF, Jr, et al. Spirometry can be done in family physicians’ offices and alters clinical decisions in management of asthma and COPD. Chest. 2007;132:1162-1168.

8. Fuhlbrigge AL, Kitch BT, Paltiel AD, et al. FEV1 is associated with risk of asthma attacks in a pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:61-67.

9. Roorda RJ, Mezei G, Bisgaard H, Maden C. Response of preschool children with asthma symptoms to fluticasone propionate. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:540-546.

10. Baker JW, Mellon M, Wald J, Welch M, Cruz-Rivera M, Walton-Bowen K. A multiple-dosing, placebo-controlled study of budesonide inhalation suspension given once or twice daily for treatment of persistent asthma in young children and infants. Pediatrics. 1999;103:414-421.

11. Kemp JP, Skoner DP, Szefler SJ, Walton-Bowen K, Cruz-Rivera M, Smith JA. Once-daily budesonide inhalation suspension for the treatment of persistent asthma in infants and young children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;83:231-239.

12. Shapiro G, Mendelson L, Kraemer MJ, Cruz-Rivera M, Walton-Bowen K, Smith JA. Efficacy and safety of budesonide inhalation suspension (Pulmicort Respules) in young children with inhaled steroid-dependent, persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:789-796.

13. Bisgaard H, Gillies J, Groenewald M, Maden C. The effect of inhaled fluticasone propionate in the treatment of young asthmatic children: a dose comparison study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:126-131.

14. Szefler SJ, Eigen H. Budesonide inhalation suspension: a nebulized corticosteroid for persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:730-742.

15. Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Zeiger RS, et al. Long-term inhaled corticosteroids in preschool children at high risk for asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1985-1997.

16. Bisgaard H, Allen D, Milanowski J, Kalev I, Willits L, Davies P. Twelve-month safety and efficacy of inhaled fluticasone propionate in children aged 1 to 3 years with recurrent wheezing. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e87-e94.

17. Knorr B, Franchi LM, Bisgaard H, et al. Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, for the treatment of persistent asthma in children aged 2 to 5 years. Pediatrics 2001;108:e48.-

18. Russell G, Williams DA, Weller P, Price JF. Salmeterol xinafoate in children on high dose inhaled steroids. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;75:423-428.

19. Zimmerman B, D’Urzo A, Bérubé D. Efficacy and safety of formoterol Turbuhaler when added to inhaled corticosteroid treatment in children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:122-127.

20. Simons FE, Villa JR, Lee BW, et al. Montelukast added to budesonide in children with persistent asthma: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J Pediatr. 2001;138:694-698.

21. Shapiro G, Bronsky EA, LaForce CF, et al. Dose-related efficacy of budesonide administered via a dry powder inhaler in the treatment of children with moderate to severe persistent asthma. J Pediatr. 1998;132:976-982.

22. Pauwels RA, Lofdahl C-G, Postma DS, et al. for the Formoterol and Corticosteroids Establishing Therapy (FACET) International Study Group. Effect of inhaled formoterol and budesonide on exacerbations of asthma. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1405-1411.

23. Tattersfield AE, Harrison TW, Hubbard RB, Mortimer K. Safety of inhaled corticosteroids. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:171-175.

24. Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. For the GOAL Investigators Group. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:836-844.

25. O’Byrne PM, Barnes PJ, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Low dose inhaled budesonide and formoterol in mild persistent asthma: the OPTIMA randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1392-1397.

26. Masoli M, Weatherall M, Holt S, Beasley R. Moderate dose inhaled corticosteroids plus salmeterol versus higher doses of inhaled corticosteroids in symptomatic asthma. Thorax. 2005;60:730-734.

27. Bousquet J, Wenzel S, Holgate S, Lumry W, Freeman P, Fox H. Predicting response to omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, in patients with allergic asthma. Chest. 2004;125:1378-1386.

28. Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, Yancey SW, Dorinsky PM. For the SMART Study Group. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest. 2006;129:15-26.

29. Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:59-65.