User login

Some 15 years ago, when Daniel Roberts, MD, FHM, decided at the end of his medical residency that his career path was going to be that of a hospitalist, he heard the same thing. A lot.

“Geesh, don’t you think you’re going to burn out?”

The reasons for such a response are well known in HM circles: the 7-on, 7-off shift structure; the constant rounding; the push-pull between clinical, administrative, and – what many would term – clerical work.

“The truth is somewhere between,” Dr. Roberts said.

Burnout is a hot topic among hospitalists and all of health care these days, as the increasing burdens of a system in seemingly constant change have fostered pressures inside and out of hospitals. Increasingly, researchers are studying and publishing about how to recognize burnout, ways to deal with, or even proactively address the issues. Some MDs – experts in physician burnout – make a living by touring the country and talking about the issue.

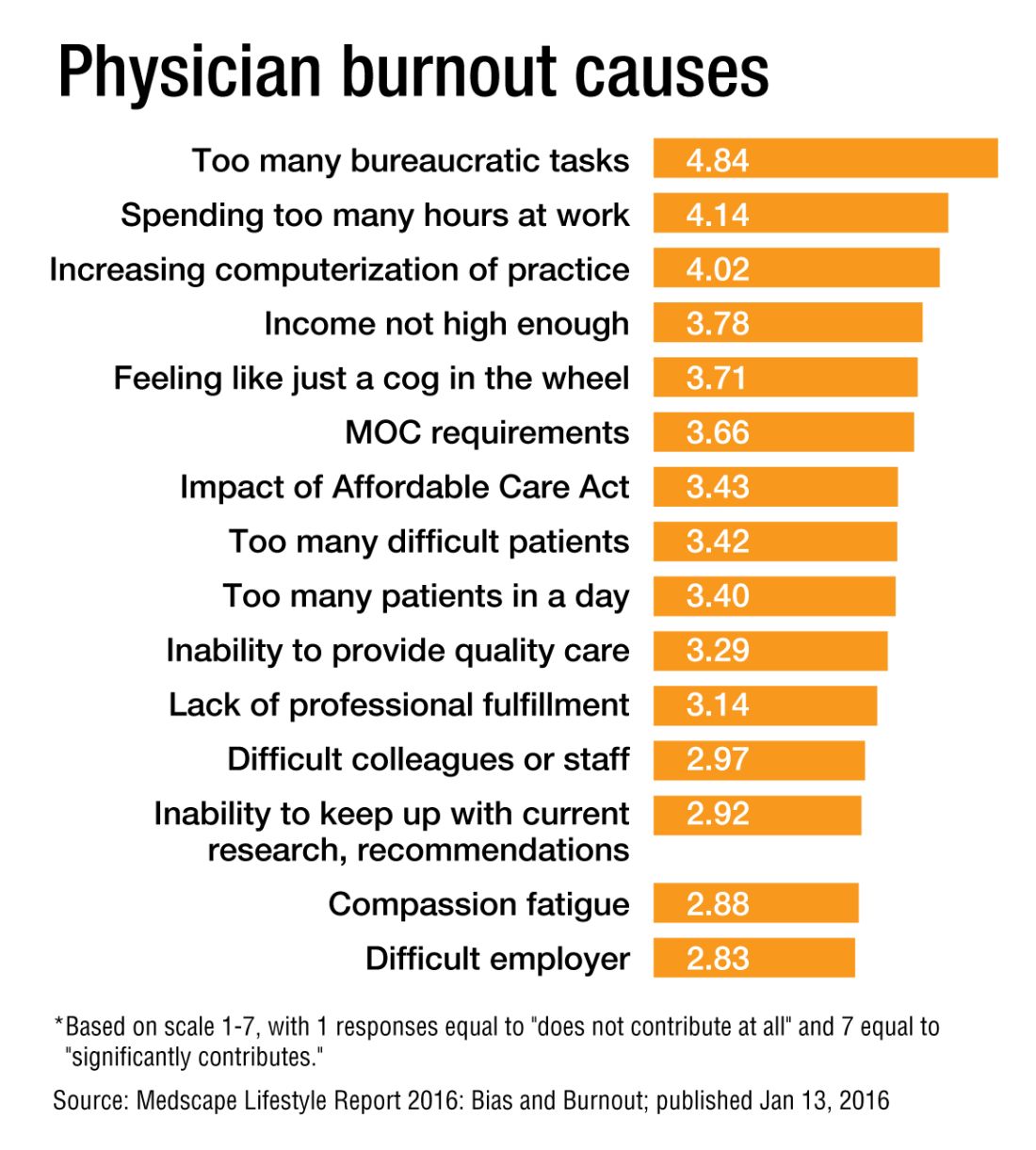

But what causes burnout, specifically and exactly?

“The simplistic answer is that burnout is what happens when resources do not meet demand,” said Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout. “The more complicated answer, which, at this point, is fairly solidly evidence based actually, is that there are five broad categories of drivers of physician distress and burnout.”

Dr. West’s hierarchy of stressors encompasses:

• Work effort.

• Work efficiency.

• Work-home interference.

• A sense of meaning.

• “Flexibility, control, and autonomy.”

Basically, the five drivers lead to this: Physicians who work too much and too inefficiently, with too little control and sense of purpose, end up flaming out more so than do doctors who work fewer hours, with fewer obstacles – all the while feeling satisfied with their autonomy and value.

Academic hospitalist John Yoon, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, says that health care has to work harder to promote its benefits as being more important than a highly paid profession. Instead, health care should focus on giving meaning to its practitioners.

“I think it is time for leaders of HM groups to honestly discuss the intrinsic meaning and essential ‘calling’ of what it means to be a good hospitalist,” Dr. Yoon wrote in an email interview with The Hospitalist. “What can we do to make the hospitalist vocation a meaningful, long-term career, so that they do not feel like simply revenue-generating ‘pawns’ in a medical-bureaucratic system?”

A ‘meaningful’ career

The modern discussion of burnout as a phenomenon traces back to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a three-pronged test that measures emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.1 But why does burnout hit physicians – hospitalists, in particular – so intensely? In part, it’s because – like their predecessors in emergency medicine – hospitalists are responsible for managing the care of patients other specialties consult with, operate on, or for whom they run tests.

“Once the patients come up from the emergency room or get admitted to the hospital from the outside, the hospitalist is the one who is largely running that show,” said Dr. West, whose researchshows that HM doctors suffer burnout more than the average across medical specialties.2 “So they’re the front line of inpatient medicine.”

Another factor contributing to burnout’s impact on hospitalists is that the specialty’s rank and file (by definition) work within the walls of institutions that have a lot of contentious and complicated issues that – while outside the purview of HM – can directly or indirectly affect the field. Dr. West calls it the hassle factor.

“You want to get a test in the hospital and, even though you’re the attending on the service, you end up going through three layers of bureaucracy with an insurance company to be able to finally get what you know that patient needs,” he said. “Anything like that contributes to the burnout problem because it pulls the physician away from what they want to be doing, what is purposeful, what is meaningful for them.”

For Dr. Yoon, the exhaustion and cynicism borne out by the work of Maslach and Dr. West’s team are measures indicative of a field where physicians struggle more and more to “make sense of why their practice is worthwhile.

“In the contemporary medical literature, we have been encouraged to adopt the concepts and practices of industrial engineering and quality improvement,” Dr. Yoon added. “In other words, it seems that to the extent physicians’ aspirations to practice good medicine are confined to the narrow and unimaginative constraints of mere scientific technique (more data, higher ‘quality,’ better outcomes) physicians will struggle to recognize and respond to their practice as meaningful. There is no intrinsic meaning to simply being a ‘cog’ in a medical-industrial process or an ‘independent variable’ in an economic equation.”

Finding meaning in one’s job, of course, is less empirical an endpoint than using a reversal agent for a GI bleed. Therein lies the challenge of battling burnout, whose causes and interventions can be as varied as the people who suffer the syndrome.

Local, customized solutions

Once a group leader identifies the symptoms of burnout, the obvious question is how to address it.

Dr. West and his colleagues have identified two broad categories of interventions: individual-focused approaches and organizational solutions. Physician-centered efforts include such tacks as mindfulness, stress reduction, resilience training and small-group communication. Institutional-level changes are, typically, much harder to implement and make successful.

“It doesn’t make sense to ... simply send physicians to stress-management training so that they’re better equipped to deal with a system that is not working to improve itself,” Dr. West said. “The system and the leadership in that system needs to take responsibility from an organizational standpoint.”

Health care as a whole has worked to address the systems-level issue. Duty-hour regulations have been reined in for trainees to be proactive in addressing both fatigue and its inevitable endpoint: burnout.

In a report, “Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,”3 published online Dec. 5 in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers concluded that interventions associated with small benefits “may be boosted by adoption of organization-directed approaches.

“This finding provides support for the view that burnout is a problem of the whole health care organization, rather than individuals,” they wrote.

But the issue typically remains a local one, as group leaders need to realize that what could cause or contribute to burnout in one employee might be enjoyable to another.

“The prospect of doing that was daunting,” Dr. Roberts recalled. “I didn’t know much about EHRs and it was going to be a lot of meetings ... and [it] was going to take me away from patient care. It really ended up being rewarding, despite all the time and frustration, because I got to help represent the interests of my hospitalist colleagues, the physician assistants, and nurses that I work with in trying to avoid some real problems that could have arisen in the EHR.”

Doing that work appealed to Dr. Roberts, so he embraced it. That approach is one championed by Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, executive vice president of EmCare, founder and CEO of BestPractices Inc., medical director for the NFL Players Association, and clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington, and University of Virginia, Charlottesville. Dr. Mayer travels the country talking about burnout and suggests a three-pronged approach.

First, find what you like about your job and maximize those duties.

Second, label those tasks that are tolerable and don’t allow them to become issues leading to burnout.

Third, and perhaps most difficult, “take the things [you] hate and eliminate them to the best extent possible from [your] job.”

“I’ll give you an example,” he said. “What I hear from emergency physicians and hospitalists is: ‘What do I hate? Well, I hate chronic pain patients.’ Well, does that mean you’re going to be able to eliminate the fact that there are chronic pain patients? No. But, what you can do is ... really drill down on it, and say ‘Why do you hate that?’ The answer is, “Well, I don’t have a strategy for it.” No one likes doing things when they don’t know what they’re doing.

“Now you take the chronic pain patient and the problem is, most of us just haven’t really thought that out. Most of us haven’t sat down with our colleagues and said, “What are you doing that’s working? How are you handling these people? What are the scripts that I can use, the evidence-based language that I can use? What alternatives can I give them?” Instead of just assuming that the only answer to the problem of chronic pain is opioids.”

The silent epidemic

So if there are measurements for burnout, and even best practices on how to address it, why is the issue one that Dr. Mayer calls a silent epidemic? One word: stigma.

“We as physicians can’t afford to propagate that stigma any further,” Dr. Roberts said. “People who have even tougher jobs than we have, involving combat and hostage negotiation and things like that, have found a way to have honest conversations about the impact of their work on their lives. There is no reason physicians shouldn’t be able to slowly change the culture of medicine to be able to do that, so that there isn’t a stigma around saying, ‘I need some time away before this begins to impact the safety of our patients.’ ”

Dr. West said that when data show that as many as half of all physicians show symptoms of burnout, there is no need to stigmatize a group that large.

Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician, coach, and consultant on burnout prevention, said that the No. 1 mistake physicians and leaders make about burnout is labeling it a “problem.”

“Burnout does not have a single solution because it is not a problem to begin with,” he added. “Burnout is a classic dilemma – a never-ending balancing act. Think of the balancing act of burnout as a teeter-totter, like the one you see in a children’s playground. On one side is the energy you put into your practice and larger life … and on the other side your ability to recharge your energy levels.

“To prevent burnout you must keep your energy expenditure and your recharge activities in balance to keep this teeter-totter in a relatively horizontal position. And the way you address the dilemma is with a strategy: three to five individual tools you use to lower your stress levels or recharge your energy balance.”

And a strategy is a long-term approach to a long-term problem, he said.

“Burnout is not necessarily a terminal condition,” Dr. Roberts said. “If we can structure their work and the balance in their life in such a way that they don’t experience it, or that when they do experience it, they can recognize it and make the changes they need to avoid it getting worse, I think we’d be better off as a profession.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

1. Maslach C, Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behavior. 1981;2:99-113

2. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-81.

3. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Brower P. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online Dec. 5, 2016 ahead of print]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674.

Some 15 years ago, when Daniel Roberts, MD, FHM, decided at the end of his medical residency that his career path was going to be that of a hospitalist, he heard the same thing. A lot.

“Geesh, don’t you think you’re going to burn out?”

The reasons for such a response are well known in HM circles: the 7-on, 7-off shift structure; the constant rounding; the push-pull between clinical, administrative, and – what many would term – clerical work.

“The truth is somewhere between,” Dr. Roberts said.

Burnout is a hot topic among hospitalists and all of health care these days, as the increasing burdens of a system in seemingly constant change have fostered pressures inside and out of hospitals. Increasingly, researchers are studying and publishing about how to recognize burnout, ways to deal with, or even proactively address the issues. Some MDs – experts in physician burnout – make a living by touring the country and talking about the issue.

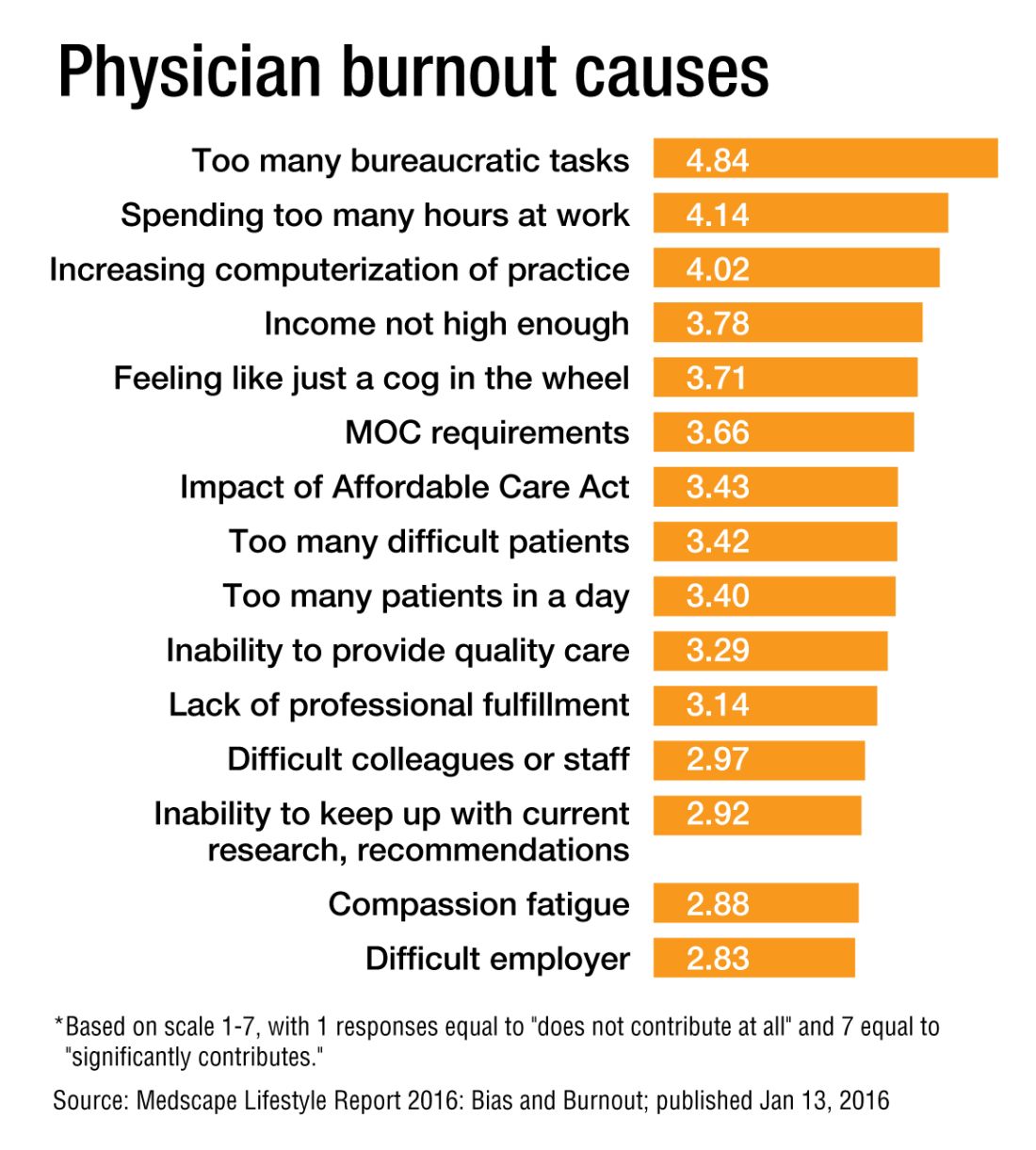

But what causes burnout, specifically and exactly?

“The simplistic answer is that burnout is what happens when resources do not meet demand,” said Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout. “The more complicated answer, which, at this point, is fairly solidly evidence based actually, is that there are five broad categories of drivers of physician distress and burnout.”

Dr. West’s hierarchy of stressors encompasses:

• Work effort.

• Work efficiency.

• Work-home interference.

• A sense of meaning.

• “Flexibility, control, and autonomy.”

Basically, the five drivers lead to this: Physicians who work too much and too inefficiently, with too little control and sense of purpose, end up flaming out more so than do doctors who work fewer hours, with fewer obstacles – all the while feeling satisfied with their autonomy and value.

Academic hospitalist John Yoon, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, says that health care has to work harder to promote its benefits as being more important than a highly paid profession. Instead, health care should focus on giving meaning to its practitioners.

“I think it is time for leaders of HM groups to honestly discuss the intrinsic meaning and essential ‘calling’ of what it means to be a good hospitalist,” Dr. Yoon wrote in an email interview with The Hospitalist. “What can we do to make the hospitalist vocation a meaningful, long-term career, so that they do not feel like simply revenue-generating ‘pawns’ in a medical-bureaucratic system?”

A ‘meaningful’ career

The modern discussion of burnout as a phenomenon traces back to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a three-pronged test that measures emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.1 But why does burnout hit physicians – hospitalists, in particular – so intensely? In part, it’s because – like their predecessors in emergency medicine – hospitalists are responsible for managing the care of patients other specialties consult with, operate on, or for whom they run tests.

“Once the patients come up from the emergency room or get admitted to the hospital from the outside, the hospitalist is the one who is largely running that show,” said Dr. West, whose researchshows that HM doctors suffer burnout more than the average across medical specialties.2 “So they’re the front line of inpatient medicine.”

Another factor contributing to burnout’s impact on hospitalists is that the specialty’s rank and file (by definition) work within the walls of institutions that have a lot of contentious and complicated issues that – while outside the purview of HM – can directly or indirectly affect the field. Dr. West calls it the hassle factor.

“You want to get a test in the hospital and, even though you’re the attending on the service, you end up going through three layers of bureaucracy with an insurance company to be able to finally get what you know that patient needs,” he said. “Anything like that contributes to the burnout problem because it pulls the physician away from what they want to be doing, what is purposeful, what is meaningful for them.”

For Dr. Yoon, the exhaustion and cynicism borne out by the work of Maslach and Dr. West’s team are measures indicative of a field where physicians struggle more and more to “make sense of why their practice is worthwhile.

“In the contemporary medical literature, we have been encouraged to adopt the concepts and practices of industrial engineering and quality improvement,” Dr. Yoon added. “In other words, it seems that to the extent physicians’ aspirations to practice good medicine are confined to the narrow and unimaginative constraints of mere scientific technique (more data, higher ‘quality,’ better outcomes) physicians will struggle to recognize and respond to their practice as meaningful. There is no intrinsic meaning to simply being a ‘cog’ in a medical-industrial process or an ‘independent variable’ in an economic equation.”

Finding meaning in one’s job, of course, is less empirical an endpoint than using a reversal agent for a GI bleed. Therein lies the challenge of battling burnout, whose causes and interventions can be as varied as the people who suffer the syndrome.

Local, customized solutions

Once a group leader identifies the symptoms of burnout, the obvious question is how to address it.

Dr. West and his colleagues have identified two broad categories of interventions: individual-focused approaches and organizational solutions. Physician-centered efforts include such tacks as mindfulness, stress reduction, resilience training and small-group communication. Institutional-level changes are, typically, much harder to implement and make successful.

“It doesn’t make sense to ... simply send physicians to stress-management training so that they’re better equipped to deal with a system that is not working to improve itself,” Dr. West said. “The system and the leadership in that system needs to take responsibility from an organizational standpoint.”

Health care as a whole has worked to address the systems-level issue. Duty-hour regulations have been reined in for trainees to be proactive in addressing both fatigue and its inevitable endpoint: burnout.

In a report, “Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,”3 published online Dec. 5 in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers concluded that interventions associated with small benefits “may be boosted by adoption of organization-directed approaches.

“This finding provides support for the view that burnout is a problem of the whole health care organization, rather than individuals,” they wrote.

But the issue typically remains a local one, as group leaders need to realize that what could cause or contribute to burnout in one employee might be enjoyable to another.

“The prospect of doing that was daunting,” Dr. Roberts recalled. “I didn’t know much about EHRs and it was going to be a lot of meetings ... and [it] was going to take me away from patient care. It really ended up being rewarding, despite all the time and frustration, because I got to help represent the interests of my hospitalist colleagues, the physician assistants, and nurses that I work with in trying to avoid some real problems that could have arisen in the EHR.”

Doing that work appealed to Dr. Roberts, so he embraced it. That approach is one championed by Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, executive vice president of EmCare, founder and CEO of BestPractices Inc., medical director for the NFL Players Association, and clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington, and University of Virginia, Charlottesville. Dr. Mayer travels the country talking about burnout and suggests a three-pronged approach.

First, find what you like about your job and maximize those duties.

Second, label those tasks that are tolerable and don’t allow them to become issues leading to burnout.

Third, and perhaps most difficult, “take the things [you] hate and eliminate them to the best extent possible from [your] job.”

“I’ll give you an example,” he said. “What I hear from emergency physicians and hospitalists is: ‘What do I hate? Well, I hate chronic pain patients.’ Well, does that mean you’re going to be able to eliminate the fact that there are chronic pain patients? No. But, what you can do is ... really drill down on it, and say ‘Why do you hate that?’ The answer is, “Well, I don’t have a strategy for it.” No one likes doing things when they don’t know what they’re doing.

“Now you take the chronic pain patient and the problem is, most of us just haven’t really thought that out. Most of us haven’t sat down with our colleagues and said, “What are you doing that’s working? How are you handling these people? What are the scripts that I can use, the evidence-based language that I can use? What alternatives can I give them?” Instead of just assuming that the only answer to the problem of chronic pain is opioids.”

The silent epidemic

So if there are measurements for burnout, and even best practices on how to address it, why is the issue one that Dr. Mayer calls a silent epidemic? One word: stigma.

“We as physicians can’t afford to propagate that stigma any further,” Dr. Roberts said. “People who have even tougher jobs than we have, involving combat and hostage negotiation and things like that, have found a way to have honest conversations about the impact of their work on their lives. There is no reason physicians shouldn’t be able to slowly change the culture of medicine to be able to do that, so that there isn’t a stigma around saying, ‘I need some time away before this begins to impact the safety of our patients.’ ”

Dr. West said that when data show that as many as half of all physicians show symptoms of burnout, there is no need to stigmatize a group that large.

Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician, coach, and consultant on burnout prevention, said that the No. 1 mistake physicians and leaders make about burnout is labeling it a “problem.”

“Burnout does not have a single solution because it is not a problem to begin with,” he added. “Burnout is a classic dilemma – a never-ending balancing act. Think of the balancing act of burnout as a teeter-totter, like the one you see in a children’s playground. On one side is the energy you put into your practice and larger life … and on the other side your ability to recharge your energy levels.

“To prevent burnout you must keep your energy expenditure and your recharge activities in balance to keep this teeter-totter in a relatively horizontal position. And the way you address the dilemma is with a strategy: three to five individual tools you use to lower your stress levels or recharge your energy balance.”

And a strategy is a long-term approach to a long-term problem, he said.

“Burnout is not necessarily a terminal condition,” Dr. Roberts said. “If we can structure their work and the balance in their life in such a way that they don’t experience it, or that when they do experience it, they can recognize it and make the changes they need to avoid it getting worse, I think we’d be better off as a profession.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

1. Maslach C, Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behavior. 1981;2:99-113

2. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-81.

3. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Brower P. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online Dec. 5, 2016 ahead of print]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674.

Some 15 years ago, when Daniel Roberts, MD, FHM, decided at the end of his medical residency that his career path was going to be that of a hospitalist, he heard the same thing. A lot.

“Geesh, don’t you think you’re going to burn out?”

The reasons for such a response are well known in HM circles: the 7-on, 7-off shift structure; the constant rounding; the push-pull between clinical, administrative, and – what many would term – clerical work.

“The truth is somewhere between,” Dr. Roberts said.

Burnout is a hot topic among hospitalists and all of health care these days, as the increasing burdens of a system in seemingly constant change have fostered pressures inside and out of hospitals. Increasingly, researchers are studying and publishing about how to recognize burnout, ways to deal with, or even proactively address the issues. Some MDs – experts in physician burnout – make a living by touring the country and talking about the issue.

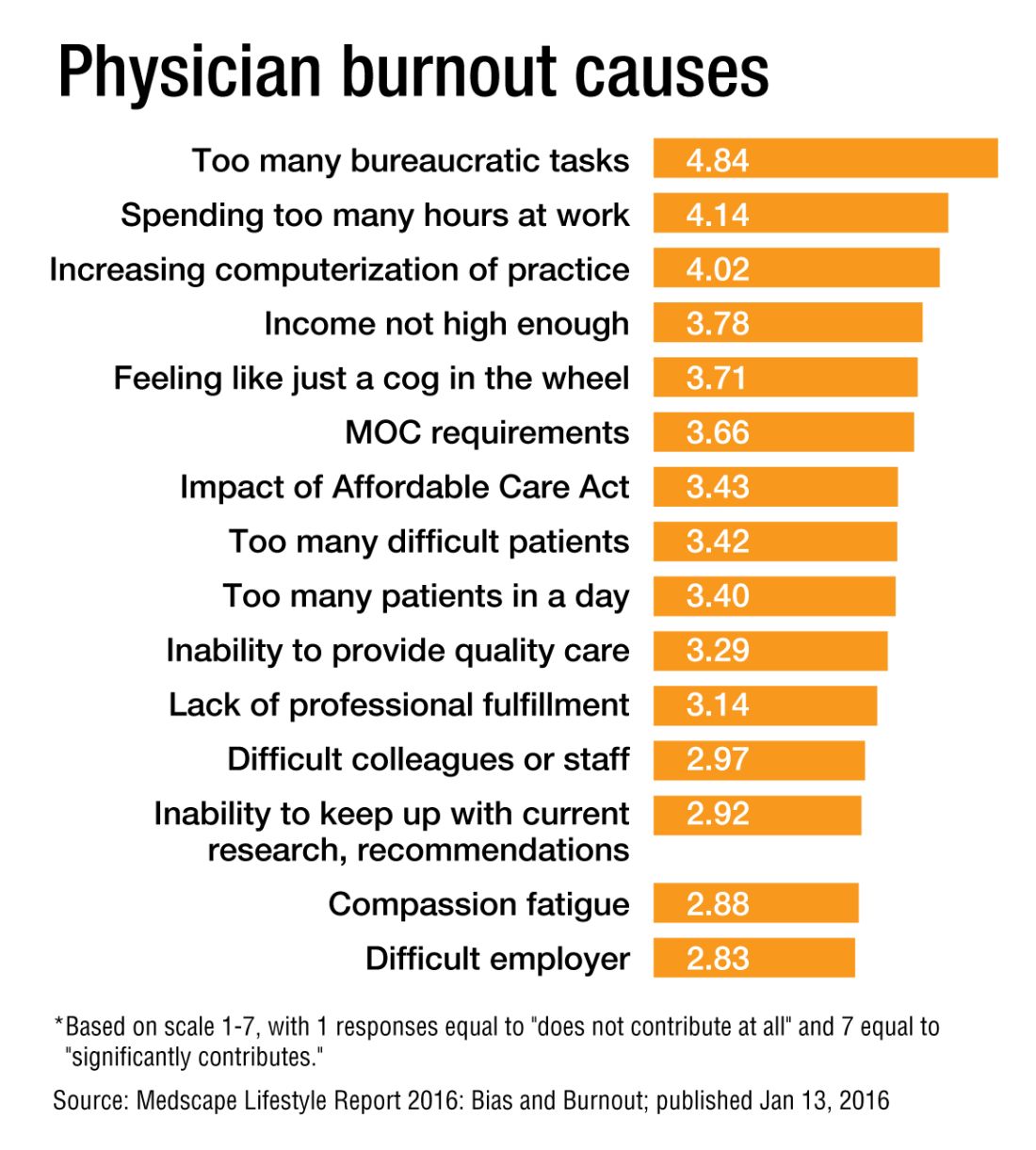

But what causes burnout, specifically and exactly?

“The simplistic answer is that burnout is what happens when resources do not meet demand,” said Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout. “The more complicated answer, which, at this point, is fairly solidly evidence based actually, is that there are five broad categories of drivers of physician distress and burnout.”

Dr. West’s hierarchy of stressors encompasses:

• Work effort.

• Work efficiency.

• Work-home interference.

• A sense of meaning.

• “Flexibility, control, and autonomy.”

Basically, the five drivers lead to this: Physicians who work too much and too inefficiently, with too little control and sense of purpose, end up flaming out more so than do doctors who work fewer hours, with fewer obstacles – all the while feeling satisfied with their autonomy and value.

Academic hospitalist John Yoon, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, says that health care has to work harder to promote its benefits as being more important than a highly paid profession. Instead, health care should focus on giving meaning to its practitioners.

“I think it is time for leaders of HM groups to honestly discuss the intrinsic meaning and essential ‘calling’ of what it means to be a good hospitalist,” Dr. Yoon wrote in an email interview with The Hospitalist. “What can we do to make the hospitalist vocation a meaningful, long-term career, so that they do not feel like simply revenue-generating ‘pawns’ in a medical-bureaucratic system?”

A ‘meaningful’ career

The modern discussion of burnout as a phenomenon traces back to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a three-pronged test that measures emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.1 But why does burnout hit physicians – hospitalists, in particular – so intensely? In part, it’s because – like their predecessors in emergency medicine – hospitalists are responsible for managing the care of patients other specialties consult with, operate on, or for whom they run tests.

“Once the patients come up from the emergency room or get admitted to the hospital from the outside, the hospitalist is the one who is largely running that show,” said Dr. West, whose researchshows that HM doctors suffer burnout more than the average across medical specialties.2 “So they’re the front line of inpatient medicine.”

Another factor contributing to burnout’s impact on hospitalists is that the specialty’s rank and file (by definition) work within the walls of institutions that have a lot of contentious and complicated issues that – while outside the purview of HM – can directly or indirectly affect the field. Dr. West calls it the hassle factor.

“You want to get a test in the hospital and, even though you’re the attending on the service, you end up going through three layers of bureaucracy with an insurance company to be able to finally get what you know that patient needs,” he said. “Anything like that contributes to the burnout problem because it pulls the physician away from what they want to be doing, what is purposeful, what is meaningful for them.”

For Dr. Yoon, the exhaustion and cynicism borne out by the work of Maslach and Dr. West’s team are measures indicative of a field where physicians struggle more and more to “make sense of why their practice is worthwhile.

“In the contemporary medical literature, we have been encouraged to adopt the concepts and practices of industrial engineering and quality improvement,” Dr. Yoon added. “In other words, it seems that to the extent physicians’ aspirations to practice good medicine are confined to the narrow and unimaginative constraints of mere scientific technique (more data, higher ‘quality,’ better outcomes) physicians will struggle to recognize and respond to their practice as meaningful. There is no intrinsic meaning to simply being a ‘cog’ in a medical-industrial process or an ‘independent variable’ in an economic equation.”

Finding meaning in one’s job, of course, is less empirical an endpoint than using a reversal agent for a GI bleed. Therein lies the challenge of battling burnout, whose causes and interventions can be as varied as the people who suffer the syndrome.

Local, customized solutions

Once a group leader identifies the symptoms of burnout, the obvious question is how to address it.

Dr. West and his colleagues have identified two broad categories of interventions: individual-focused approaches and organizational solutions. Physician-centered efforts include such tacks as mindfulness, stress reduction, resilience training and small-group communication. Institutional-level changes are, typically, much harder to implement and make successful.

“It doesn’t make sense to ... simply send physicians to stress-management training so that they’re better equipped to deal with a system that is not working to improve itself,” Dr. West said. “The system and the leadership in that system needs to take responsibility from an organizational standpoint.”

Health care as a whole has worked to address the systems-level issue. Duty-hour regulations have been reined in for trainees to be proactive in addressing both fatigue and its inevitable endpoint: burnout.

In a report, “Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,”3 published online Dec. 5 in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers concluded that interventions associated with small benefits “may be boosted by adoption of organization-directed approaches.

“This finding provides support for the view that burnout is a problem of the whole health care organization, rather than individuals,” they wrote.

But the issue typically remains a local one, as group leaders need to realize that what could cause or contribute to burnout in one employee might be enjoyable to another.

“The prospect of doing that was daunting,” Dr. Roberts recalled. “I didn’t know much about EHRs and it was going to be a lot of meetings ... and [it] was going to take me away from patient care. It really ended up being rewarding, despite all the time and frustration, because I got to help represent the interests of my hospitalist colleagues, the physician assistants, and nurses that I work with in trying to avoid some real problems that could have arisen in the EHR.”

Doing that work appealed to Dr. Roberts, so he embraced it. That approach is one championed by Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, executive vice president of EmCare, founder and CEO of BestPractices Inc., medical director for the NFL Players Association, and clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington, and University of Virginia, Charlottesville. Dr. Mayer travels the country talking about burnout and suggests a three-pronged approach.

First, find what you like about your job and maximize those duties.

Second, label those tasks that are tolerable and don’t allow them to become issues leading to burnout.

Third, and perhaps most difficult, “take the things [you] hate and eliminate them to the best extent possible from [your] job.”

“I’ll give you an example,” he said. “What I hear from emergency physicians and hospitalists is: ‘What do I hate? Well, I hate chronic pain patients.’ Well, does that mean you’re going to be able to eliminate the fact that there are chronic pain patients? No. But, what you can do is ... really drill down on it, and say ‘Why do you hate that?’ The answer is, “Well, I don’t have a strategy for it.” No one likes doing things when they don’t know what they’re doing.

“Now you take the chronic pain patient and the problem is, most of us just haven’t really thought that out. Most of us haven’t sat down with our colleagues and said, “What are you doing that’s working? How are you handling these people? What are the scripts that I can use, the evidence-based language that I can use? What alternatives can I give them?” Instead of just assuming that the only answer to the problem of chronic pain is opioids.”

The silent epidemic

So if there are measurements for burnout, and even best practices on how to address it, why is the issue one that Dr. Mayer calls a silent epidemic? One word: stigma.

“We as physicians can’t afford to propagate that stigma any further,” Dr. Roberts said. “People who have even tougher jobs than we have, involving combat and hostage negotiation and things like that, have found a way to have honest conversations about the impact of their work on their lives. There is no reason physicians shouldn’t be able to slowly change the culture of medicine to be able to do that, so that there isn’t a stigma around saying, ‘I need some time away before this begins to impact the safety of our patients.’ ”

Dr. West said that when data show that as many as half of all physicians show symptoms of burnout, there is no need to stigmatize a group that large.

Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician, coach, and consultant on burnout prevention, said that the No. 1 mistake physicians and leaders make about burnout is labeling it a “problem.”

“Burnout does not have a single solution because it is not a problem to begin with,” he added. “Burnout is a classic dilemma – a never-ending balancing act. Think of the balancing act of burnout as a teeter-totter, like the one you see in a children’s playground. On one side is the energy you put into your practice and larger life … and on the other side your ability to recharge your energy levels.

“To prevent burnout you must keep your energy expenditure and your recharge activities in balance to keep this teeter-totter in a relatively horizontal position. And the way you address the dilemma is with a strategy: three to five individual tools you use to lower your stress levels or recharge your energy balance.”

And a strategy is a long-term approach to a long-term problem, he said.

“Burnout is not necessarily a terminal condition,” Dr. Roberts said. “If we can structure their work and the balance in their life in such a way that they don’t experience it, or that when they do experience it, they can recognize it and make the changes they need to avoid it getting worse, I think we’d be better off as a profession.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

1. Maslach C, Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behavior. 1981;2:99-113

2. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-81.

3. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Brower P. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online Dec. 5, 2016 ahead of print]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674.