User login

In his book, Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance, Atul Gawande asks the question, “What does it take to be good at something in which failure is so easy, so effortless?”1 Consider this statement for just a moment. Every day, over 355,000 patents seek care in this nation’s EDs.2 These visits have a wide-range of significance, from the low acuity and low impact self-limited problems to the cases in which every decision and every second counts. Reflect on the 1999 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, “To Err is Human.” At that time, 16 years ago, this seminal work estimated that up to 98,000 people die each year (268 each day) as a result of errors made in US hospitals.3 Variability in documentation, for many reasons, is a plausible factor in underestimation of accurate numbers. Since 2001, the worrisome number of deaths reported by the IOM has been re-evaluated a number of times, with each successive “deep dive” looking more ominous than the last.

In 2013, John James published a more recent estimate of preventable adverse events in the Journal of Patient Safety.4 He applied a literature review method to target the Global Trigger Tool from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement as the litmus test to estimate preventable error. In this limited review, James found that between 210,000 and over 400,000 premature deaths per year (575-1,095 deaths per day) are associated with harm that is preventable in hospitals. This number accounts for approximately 17% of the annual US population mortality and exceeds the national death toll from chronic lower respiratory tract infections, strokes, and accidents.5 Estimates of serious harm events (ie, morbidity) appear to be significantly greater than mortality. The adoption of the electronic medical record has not eliminated inaccuracies due to variation in documentation, reluctance of providers to report known errors, and lack of patient perspective in the recounting of their medical stories. The enormous magnitude of public-health consequences due to medical errors thus seems clear.

We become doctors and nurses primarily to help people, and not to cause harm to anyone. When harm occurs as the result of medical errors, the gut-wrenching guilt and self-deprecation that follows for most of us, and the doubt cast on our abilities as physicians, raise the question of why errors happen, and why more is not done to prevent them or to mitigate the consequences.

An awareness of some of the circumstances that lead to error can be a tremendous help in its prevention. High reliability organizations recognize that humans are fallible and that variation in human factors contributes to error, while also focusing on building safer environments designed to create layers of defense against error and mitigate their impact. Blame, shame, and accusatory approaches fail to improve any type of error. Environmental and situational hazards such as ED overcrowding, understaffing, high-patient volumes, rigid throughput demands, lack of equipment/subspecialty services and support in the system are highly contributory and must be addressed. Systemic issues aside, there are compelling individual factors that can lead anyone to make a mistake. Although lessons learned from mistakes are paramount to improvement, an understanding and awareness of the science of error and the necessity of “mindful medicine” can help protect individuals from the personal tolls of making a mistake.

Cognitive Biases

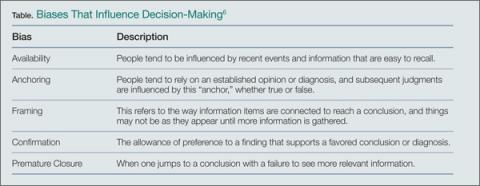

There are five significant cognitive biases that can result in preventable errors: availability bias, anchoring bias, framing bias, confirmation bias, and premature closure. Availability bias favors the common diagnosis without proving its validity. Anchoring bias occurs when a prior diagnosis or opinion is favored and misleads one from the correct current diagnosis. Framing bias can occur when it is not recognized that the data fail to fit the diagnostic presumptions. Confirmation bias can result when information is selectively interpreted to confirm a belief. Premature closure can lead hastily to an incorrect, rushed diagnostic conclusion. The following case scenarios illustrate examples of each of these biases.

Case Scenario 1: The Most Common Diagnosis Versus Looking for the Needle in the Haystack

On a busy night in the ED, the fifth patient of an emergency physician’s (EP) fourth consecutive shift was a quiet young lady home from college during the flu season. With a temperature of 102.6˚F, a heart rate of 110 beats/minute, blood pressure of 105/68 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 16 breaths/minute, and an oxygen saturation of 100% on room air, the EP was confident she would see another case of influenza. With the patient’s body aches, fever, and cough, she clearly appeared to be suffering from the flu, just like so many others this particular week. After treating the patient with fluids, antipyretics, and reassurance, she was sent home to rest in her own bed, with care instructions for influenza.

Because influenza was prevalent in the community, and a myriad of patients with the virus were seen this particular week, the EP was assured that this young lady had the flu—until she returned the next day with a petechial rash and sepsis from bacterial meningitis. This case illustrates the influence of “availability bias” in decision making. Treating a myriad of patients with the same symptoms, some with positive influenza screens and others with negative screens, led the physician to believe that the correct diagnosis, influenza for this patient, was the most common, some might say logical, diagnosis, while discounting other, and more serious possibilities as improbable.

By referring to the disease process that comes to mind most easily, and basing a diagnosis on previous patient experiences with similar symptoms, availability bias confounded the ability to look deeper into other possible causes. A more thorough neck examination, and careful skin and neurological examinations, coupled with the knowledge of a negative rapid influenza test, might have provided enough information—or doubt—to change the physician’s frame of reference and initially establish the correct diagnosis.

“Availability Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Always take a moment to consider diagnoses other than the most common in the differential and prove why the common diagnosis is valid and why other diagnoses could not be the case. If unable to do so, go back and re-evaluate.

Case Scenario 2: It Is Not Always ‘What It Is’

The next patient, a woman in her late 20s, presented to the ED less than 48 hours after discharge from the trauma service at another hospital. She had been admitted after a motor vehicle accident that resulted in an isolated traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. After observation, with no surgical intervention, she was discharged in good condition and was able to resume her normal activities with supportive care for a persistent headache postinjury. However, the patient returned after 2 days to an ED closer to her home, because she felt “foggy” and more irritable than usual.

As is customary, this busy unit employs nursing preemptive (ie, standing) orders, and the patient was triaged and laboratory tests were drawn including a basic chemistry panel. Upon evaluation by the attending EP, a concern for re-bleed led to a request for a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head, which was interpreted as stable with no new bleed. The case was discussed with the trauma service from the initial hospital and follow-up was arranged.

Prior to the follow-up appointment, the patient returned to the ED because of a further deterioration in mental status. A third head CT was taken and interpreted as stable; however, her serum sodium level was 114 mmol/L. This patient suffered from posttraumatic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), and a retrospective review of the laboratory values from the prior ED visit showed the sodium level to be abnormally low at 121 mmol/L.

This case is a good illustration of “anchoring bias,” in which the existing diagnosis of traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage was maintained as the etiology of the patient’s symptoms, despite a new piece of significant information (ie, the low sodium level) that was not integrated into the differential of possible etiologies for continued deterioration of mental status.

“Anchoring Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Awareness of the power of a prior diagnosis or opinion to mislead is paramount; be sure to carefully review all available data and account for anything that does not lie within the range expected for your diagnosis whenever a patient returns to the ED.

Case Scenario 3: The Search for the Right Piece of the Puzzle

A merchant marine in his mid-40s had fever, jaundice, vomiting, and right upper-quadrant pain for 2 days. He had been airlifted off his ship in the mid-Atlantic Ocean because the medical crew on the ship was concerned that he had a life-threatening illness and they had no surgical facilities available to care for acute cholecystitis with ascending cholangitis.

This patient was otherwise healthy and had all current immunizations. Upon arrival in the ED, he was given intravenous (IV) fluids, antiemetics, and medication for pain control while the workup was underway. He was somnolent and critically ill-appearing. As he spoke only German, a Red Cross interpreter was engaged in an attempt to obtain further information, but the patient was unable to provide additional history. The physician was able to elicit the travel history of the ship by connecting the interpreter with a crewmember on board and learned that the ship was on a return voyage from Haiti, a country endemic with Plasmodium falciparum. It was further determined that this patient was not taking malaria prophylaxis; his blood smear turned out to be positive for the disease.

This case emphasizes the impact of “framing bias” in the thought process that led to the initial diagnosis of ascending cholangitis. Charcot’s Triad of fever, jaundice, and right upper-quadrant pain was the “frame” in which the suspected—yet uncommon—diagnosis was made. The frame of reference, however, changed significantly when the additional information of P. falciparum malaria exposure was elucidated, allowing the correct diagnosis to come into view.

I “Framing Bias” Mitigation Strategy: Confirm that the points of data align properly and fit within the diagnostic possibilities. If they do not connect, seek further information and widen the frame of reference.

Case Scenario 4: Mother Knows Best

The parents of an 11-year-old boy brought their child to the ED for abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that started 10 hours prior to presentation. The boy had no medical or surgical history. During the examination, his mother expressed concern for appendicitis, a common concern of parents whose children have abdominal pain.

Although the boy was uncomfortable, he had no right lower-quadrant tenderness; his bowel sounds were normal, and there was no tenderness to heel tap or Rovsing’s sign. He did have periumbilical tenderness and distractible guarding. His white blood-cell (WBC) count was 12.5 K/uL with 78% segmented neutrophils and urinalysis showed 15 WBCs/hpf with no bacteria. With IV hydration, opioid pain medication, and antiemetic medication, the patient felt much better, and the abdominal examination improved with no tenderness.

After a clear liquid trial was successful, careful counseling of the parents made it clear that appendicitis was possible, but unlikely given the improvement in symptoms, and the boy was discharged with the diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis. Six hours later, the boy was brought back to the ED and then taken to the operating room for acute appendicitis.

This case illustrates the effect of “confirmation bias,” in which the preference to favor a particular diagnosis outweighs the clinical clues that suggested the correct diagnosis. Neither possible opioid effect in masking pain nor the lack of history or complaint of diarrhea was effectively taken into consideration before making the diagnosis of “gastroenteritis.”

I “Confirmation Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Be aware that selective filtering of information to confirm a belief is wrought with danger. Seek data and information that could weaken or negate the belief and give it serious consideration.

Case Scenario 5: The “Frequent Flyer”

This case involved an extremely difficult-to-manage patient who had presented to the ED many times in the past with “the worst headache of his life.” During these visits, he was typically disruptive, problematic to discharge safely, and a particular behavioral issue for the nurses. As a result, when he presented to the ED, the goal was to evaluate him quickly, treat him humanely, and diagnose and discharge him as soon as possible. He was never accompanied by family or friends. His personal medical history was positive for uncontrolled hypertension and chronic alcoholism.

Attempts to coordinate his care with social services and community mental health were unsuccessful. On examination, his blood pressure was 210/105 mm Hg and a severe headache was once again his chief complaint. A head CT scan performed less than 12 hours prior to this presentation revealed no new findings compared with many prior CTs. However, there was a slight slurring of his speech on this visit that wasn’t part of his prior presentations. After he was given lorazepam and a meal tray, the patient felt a little better and was discharged. The patient never returned to the ED, and the staff has since become concerned that on this last ED visit, their “frequent flyer” had something real.

Although it is not known what exactly happened to this patient, the manner in which he was treated represents the effect of premature closure on the medical decision-making process. When a clinician jumps to conclusions without seeking more information, the possibility of an error in judgment exists.

I “Premature Closure” Mitigating Strategies: Never stop thinking even after a conclusion has been reached. Instead, stop and think again about what else could be happening.

Conclusion

In all of the case scenarios presented, any or all of the patients might have survived the errors made without any adverse outcome, but the errors might also have resulted in mild to severe permanent disability or death. It is important to remember that errors can happen regardless of good intentions and acceptable practice, and that although an error may have no consequence in one set of circumstances, the same error could be deadly in others.

On the systems level, approaches to assess and control the work environment are necessary to mitigate risk to individuals, create a culture of safety, and encourage collective learning and continuous improvement. Recognition of the frequent incidence of error and awareness of the overlapping cognitive biases (Table), while always being mindful to take a moment to think further, can help avoid—but never eliminate--these types of mistakes.

Dr McCammon is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

- Gawande A. Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance. New York, NY: Picador; 2007.

- National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Emergency Department Summary

- Tables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2010_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a safer health system. https://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf. Published November 1999. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- James, JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Pat Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128.

- Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61(6):1-51. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_06.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- Wellbury C. Flaws in clinical reasoning: a common cause of diagnostic error. Am Fam Physician. 2011; 84(9):1042-1048

In his book, Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance, Atul Gawande asks the question, “What does it take to be good at something in which failure is so easy, so effortless?”1 Consider this statement for just a moment. Every day, over 355,000 patents seek care in this nation’s EDs.2 These visits have a wide-range of significance, from the low acuity and low impact self-limited problems to the cases in which every decision and every second counts. Reflect on the 1999 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, “To Err is Human.” At that time, 16 years ago, this seminal work estimated that up to 98,000 people die each year (268 each day) as a result of errors made in US hospitals.3 Variability in documentation, for many reasons, is a plausible factor in underestimation of accurate numbers. Since 2001, the worrisome number of deaths reported by the IOM has been re-evaluated a number of times, with each successive “deep dive” looking more ominous than the last.

In 2013, John James published a more recent estimate of preventable adverse events in the Journal of Patient Safety.4 He applied a literature review method to target the Global Trigger Tool from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement as the litmus test to estimate preventable error. In this limited review, James found that between 210,000 and over 400,000 premature deaths per year (575-1,095 deaths per day) are associated with harm that is preventable in hospitals. This number accounts for approximately 17% of the annual US population mortality and exceeds the national death toll from chronic lower respiratory tract infections, strokes, and accidents.5 Estimates of serious harm events (ie, morbidity) appear to be significantly greater than mortality. The adoption of the electronic medical record has not eliminated inaccuracies due to variation in documentation, reluctance of providers to report known errors, and lack of patient perspective in the recounting of their medical stories. The enormous magnitude of public-health consequences due to medical errors thus seems clear.

We become doctors and nurses primarily to help people, and not to cause harm to anyone. When harm occurs as the result of medical errors, the gut-wrenching guilt and self-deprecation that follows for most of us, and the doubt cast on our abilities as physicians, raise the question of why errors happen, and why more is not done to prevent them or to mitigate the consequences.

An awareness of some of the circumstances that lead to error can be a tremendous help in its prevention. High reliability organizations recognize that humans are fallible and that variation in human factors contributes to error, while also focusing on building safer environments designed to create layers of defense against error and mitigate their impact. Blame, shame, and accusatory approaches fail to improve any type of error. Environmental and situational hazards such as ED overcrowding, understaffing, high-patient volumes, rigid throughput demands, lack of equipment/subspecialty services and support in the system are highly contributory and must be addressed. Systemic issues aside, there are compelling individual factors that can lead anyone to make a mistake. Although lessons learned from mistakes are paramount to improvement, an understanding and awareness of the science of error and the necessity of “mindful medicine” can help protect individuals from the personal tolls of making a mistake.

Cognitive Biases

There are five significant cognitive biases that can result in preventable errors: availability bias, anchoring bias, framing bias, confirmation bias, and premature closure. Availability bias favors the common diagnosis without proving its validity. Anchoring bias occurs when a prior diagnosis or opinion is favored and misleads one from the correct current diagnosis. Framing bias can occur when it is not recognized that the data fail to fit the diagnostic presumptions. Confirmation bias can result when information is selectively interpreted to confirm a belief. Premature closure can lead hastily to an incorrect, rushed diagnostic conclusion. The following case scenarios illustrate examples of each of these biases.

Case Scenario 1: The Most Common Diagnosis Versus Looking for the Needle in the Haystack

On a busy night in the ED, the fifth patient of an emergency physician’s (EP) fourth consecutive shift was a quiet young lady home from college during the flu season. With a temperature of 102.6˚F, a heart rate of 110 beats/minute, blood pressure of 105/68 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 16 breaths/minute, and an oxygen saturation of 100% on room air, the EP was confident she would see another case of influenza. With the patient’s body aches, fever, and cough, she clearly appeared to be suffering from the flu, just like so many others this particular week. After treating the patient with fluids, antipyretics, and reassurance, she was sent home to rest in her own bed, with care instructions for influenza.

Because influenza was prevalent in the community, and a myriad of patients with the virus were seen this particular week, the EP was assured that this young lady had the flu—until she returned the next day with a petechial rash and sepsis from bacterial meningitis. This case illustrates the influence of “availability bias” in decision making. Treating a myriad of patients with the same symptoms, some with positive influenza screens and others with negative screens, led the physician to believe that the correct diagnosis, influenza for this patient, was the most common, some might say logical, diagnosis, while discounting other, and more serious possibilities as improbable.

By referring to the disease process that comes to mind most easily, and basing a diagnosis on previous patient experiences with similar symptoms, availability bias confounded the ability to look deeper into other possible causes. A more thorough neck examination, and careful skin and neurological examinations, coupled with the knowledge of a negative rapid influenza test, might have provided enough information—or doubt—to change the physician’s frame of reference and initially establish the correct diagnosis.

“Availability Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Always take a moment to consider diagnoses other than the most common in the differential and prove why the common diagnosis is valid and why other diagnoses could not be the case. If unable to do so, go back and re-evaluate.

Case Scenario 2: It Is Not Always ‘What It Is’

The next patient, a woman in her late 20s, presented to the ED less than 48 hours after discharge from the trauma service at another hospital. She had been admitted after a motor vehicle accident that resulted in an isolated traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. After observation, with no surgical intervention, she was discharged in good condition and was able to resume her normal activities with supportive care for a persistent headache postinjury. However, the patient returned after 2 days to an ED closer to her home, because she felt “foggy” and more irritable than usual.

As is customary, this busy unit employs nursing preemptive (ie, standing) orders, and the patient was triaged and laboratory tests were drawn including a basic chemistry panel. Upon evaluation by the attending EP, a concern for re-bleed led to a request for a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head, which was interpreted as stable with no new bleed. The case was discussed with the trauma service from the initial hospital and follow-up was arranged.

Prior to the follow-up appointment, the patient returned to the ED because of a further deterioration in mental status. A third head CT was taken and interpreted as stable; however, her serum sodium level was 114 mmol/L. This patient suffered from posttraumatic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), and a retrospective review of the laboratory values from the prior ED visit showed the sodium level to be abnormally low at 121 mmol/L.

This case is a good illustration of “anchoring bias,” in which the existing diagnosis of traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage was maintained as the etiology of the patient’s symptoms, despite a new piece of significant information (ie, the low sodium level) that was not integrated into the differential of possible etiologies for continued deterioration of mental status.

“Anchoring Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Awareness of the power of a prior diagnosis or opinion to mislead is paramount; be sure to carefully review all available data and account for anything that does not lie within the range expected for your diagnosis whenever a patient returns to the ED.

Case Scenario 3: The Search for the Right Piece of the Puzzle

A merchant marine in his mid-40s had fever, jaundice, vomiting, and right upper-quadrant pain for 2 days. He had been airlifted off his ship in the mid-Atlantic Ocean because the medical crew on the ship was concerned that he had a life-threatening illness and they had no surgical facilities available to care for acute cholecystitis with ascending cholangitis.

This patient was otherwise healthy and had all current immunizations. Upon arrival in the ED, he was given intravenous (IV) fluids, antiemetics, and medication for pain control while the workup was underway. He was somnolent and critically ill-appearing. As he spoke only German, a Red Cross interpreter was engaged in an attempt to obtain further information, but the patient was unable to provide additional history. The physician was able to elicit the travel history of the ship by connecting the interpreter with a crewmember on board and learned that the ship was on a return voyage from Haiti, a country endemic with Plasmodium falciparum. It was further determined that this patient was not taking malaria prophylaxis; his blood smear turned out to be positive for the disease.

This case emphasizes the impact of “framing bias” in the thought process that led to the initial diagnosis of ascending cholangitis. Charcot’s Triad of fever, jaundice, and right upper-quadrant pain was the “frame” in which the suspected—yet uncommon—diagnosis was made. The frame of reference, however, changed significantly when the additional information of P. falciparum malaria exposure was elucidated, allowing the correct diagnosis to come into view.

I “Framing Bias” Mitigation Strategy: Confirm that the points of data align properly and fit within the diagnostic possibilities. If they do not connect, seek further information and widen the frame of reference.

Case Scenario 4: Mother Knows Best

The parents of an 11-year-old boy brought their child to the ED for abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that started 10 hours prior to presentation. The boy had no medical or surgical history. During the examination, his mother expressed concern for appendicitis, a common concern of parents whose children have abdominal pain.

Although the boy was uncomfortable, he had no right lower-quadrant tenderness; his bowel sounds were normal, and there was no tenderness to heel tap or Rovsing’s sign. He did have periumbilical tenderness and distractible guarding. His white blood-cell (WBC) count was 12.5 K/uL with 78% segmented neutrophils and urinalysis showed 15 WBCs/hpf with no bacteria. With IV hydration, opioid pain medication, and antiemetic medication, the patient felt much better, and the abdominal examination improved with no tenderness.

After a clear liquid trial was successful, careful counseling of the parents made it clear that appendicitis was possible, but unlikely given the improvement in symptoms, and the boy was discharged with the diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis. Six hours later, the boy was brought back to the ED and then taken to the operating room for acute appendicitis.

This case illustrates the effect of “confirmation bias,” in which the preference to favor a particular diagnosis outweighs the clinical clues that suggested the correct diagnosis. Neither possible opioid effect in masking pain nor the lack of history or complaint of diarrhea was effectively taken into consideration before making the diagnosis of “gastroenteritis.”

I “Confirmation Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Be aware that selective filtering of information to confirm a belief is wrought with danger. Seek data and information that could weaken or negate the belief and give it serious consideration.

Case Scenario 5: The “Frequent Flyer”

This case involved an extremely difficult-to-manage patient who had presented to the ED many times in the past with “the worst headache of his life.” During these visits, he was typically disruptive, problematic to discharge safely, and a particular behavioral issue for the nurses. As a result, when he presented to the ED, the goal was to evaluate him quickly, treat him humanely, and diagnose and discharge him as soon as possible. He was never accompanied by family or friends. His personal medical history was positive for uncontrolled hypertension and chronic alcoholism.

Attempts to coordinate his care with social services and community mental health were unsuccessful. On examination, his blood pressure was 210/105 mm Hg and a severe headache was once again his chief complaint. A head CT scan performed less than 12 hours prior to this presentation revealed no new findings compared with many prior CTs. However, there was a slight slurring of his speech on this visit that wasn’t part of his prior presentations. After he was given lorazepam and a meal tray, the patient felt a little better and was discharged. The patient never returned to the ED, and the staff has since become concerned that on this last ED visit, their “frequent flyer” had something real.

Although it is not known what exactly happened to this patient, the manner in which he was treated represents the effect of premature closure on the medical decision-making process. When a clinician jumps to conclusions without seeking more information, the possibility of an error in judgment exists.

I “Premature Closure” Mitigating Strategies: Never stop thinking even after a conclusion has been reached. Instead, stop and think again about what else could be happening.

Conclusion

In all of the case scenarios presented, any or all of the patients might have survived the errors made without any adverse outcome, but the errors might also have resulted in mild to severe permanent disability or death. It is important to remember that errors can happen regardless of good intentions and acceptable practice, and that although an error may have no consequence in one set of circumstances, the same error could be deadly in others.

On the systems level, approaches to assess and control the work environment are necessary to mitigate risk to individuals, create a culture of safety, and encourage collective learning and continuous improvement. Recognition of the frequent incidence of error and awareness of the overlapping cognitive biases (Table), while always being mindful to take a moment to think further, can help avoid—but never eliminate--these types of mistakes.

Dr McCammon is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

In his book, Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance, Atul Gawande asks the question, “What does it take to be good at something in which failure is so easy, so effortless?”1 Consider this statement for just a moment. Every day, over 355,000 patents seek care in this nation’s EDs.2 These visits have a wide-range of significance, from the low acuity and low impact self-limited problems to the cases in which every decision and every second counts. Reflect on the 1999 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, “To Err is Human.” At that time, 16 years ago, this seminal work estimated that up to 98,000 people die each year (268 each day) as a result of errors made in US hospitals.3 Variability in documentation, for many reasons, is a plausible factor in underestimation of accurate numbers. Since 2001, the worrisome number of deaths reported by the IOM has been re-evaluated a number of times, with each successive “deep dive” looking more ominous than the last.

In 2013, John James published a more recent estimate of preventable adverse events in the Journal of Patient Safety.4 He applied a literature review method to target the Global Trigger Tool from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement as the litmus test to estimate preventable error. In this limited review, James found that between 210,000 and over 400,000 premature deaths per year (575-1,095 deaths per day) are associated with harm that is preventable in hospitals. This number accounts for approximately 17% of the annual US population mortality and exceeds the national death toll from chronic lower respiratory tract infections, strokes, and accidents.5 Estimates of serious harm events (ie, morbidity) appear to be significantly greater than mortality. The adoption of the electronic medical record has not eliminated inaccuracies due to variation in documentation, reluctance of providers to report known errors, and lack of patient perspective in the recounting of their medical stories. The enormous magnitude of public-health consequences due to medical errors thus seems clear.

We become doctors and nurses primarily to help people, and not to cause harm to anyone. When harm occurs as the result of medical errors, the gut-wrenching guilt and self-deprecation that follows for most of us, and the doubt cast on our abilities as physicians, raise the question of why errors happen, and why more is not done to prevent them or to mitigate the consequences.

An awareness of some of the circumstances that lead to error can be a tremendous help in its prevention. High reliability organizations recognize that humans are fallible and that variation in human factors contributes to error, while also focusing on building safer environments designed to create layers of defense against error and mitigate their impact. Blame, shame, and accusatory approaches fail to improve any type of error. Environmental and situational hazards such as ED overcrowding, understaffing, high-patient volumes, rigid throughput demands, lack of equipment/subspecialty services and support in the system are highly contributory and must be addressed. Systemic issues aside, there are compelling individual factors that can lead anyone to make a mistake. Although lessons learned from mistakes are paramount to improvement, an understanding and awareness of the science of error and the necessity of “mindful medicine” can help protect individuals from the personal tolls of making a mistake.

Cognitive Biases

There are five significant cognitive biases that can result in preventable errors: availability bias, anchoring bias, framing bias, confirmation bias, and premature closure. Availability bias favors the common diagnosis without proving its validity. Anchoring bias occurs when a prior diagnosis or opinion is favored and misleads one from the correct current diagnosis. Framing bias can occur when it is not recognized that the data fail to fit the diagnostic presumptions. Confirmation bias can result when information is selectively interpreted to confirm a belief. Premature closure can lead hastily to an incorrect, rushed diagnostic conclusion. The following case scenarios illustrate examples of each of these biases.

Case Scenario 1: The Most Common Diagnosis Versus Looking for the Needle in the Haystack

On a busy night in the ED, the fifth patient of an emergency physician’s (EP) fourth consecutive shift was a quiet young lady home from college during the flu season. With a temperature of 102.6˚F, a heart rate of 110 beats/minute, blood pressure of 105/68 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 16 breaths/minute, and an oxygen saturation of 100% on room air, the EP was confident she would see another case of influenza. With the patient’s body aches, fever, and cough, she clearly appeared to be suffering from the flu, just like so many others this particular week. After treating the patient with fluids, antipyretics, and reassurance, she was sent home to rest in her own bed, with care instructions for influenza.

Because influenza was prevalent in the community, and a myriad of patients with the virus were seen this particular week, the EP was assured that this young lady had the flu—until she returned the next day with a petechial rash and sepsis from bacterial meningitis. This case illustrates the influence of “availability bias” in decision making. Treating a myriad of patients with the same symptoms, some with positive influenza screens and others with negative screens, led the physician to believe that the correct diagnosis, influenza for this patient, was the most common, some might say logical, diagnosis, while discounting other, and more serious possibilities as improbable.

By referring to the disease process that comes to mind most easily, and basing a diagnosis on previous patient experiences with similar symptoms, availability bias confounded the ability to look deeper into other possible causes. A more thorough neck examination, and careful skin and neurological examinations, coupled with the knowledge of a negative rapid influenza test, might have provided enough information—or doubt—to change the physician’s frame of reference and initially establish the correct diagnosis.

“Availability Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Always take a moment to consider diagnoses other than the most common in the differential and prove why the common diagnosis is valid and why other diagnoses could not be the case. If unable to do so, go back and re-evaluate.

Case Scenario 2: It Is Not Always ‘What It Is’

The next patient, a woman in her late 20s, presented to the ED less than 48 hours after discharge from the trauma service at another hospital. She had been admitted after a motor vehicle accident that resulted in an isolated traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. After observation, with no surgical intervention, she was discharged in good condition and was able to resume her normal activities with supportive care for a persistent headache postinjury. However, the patient returned after 2 days to an ED closer to her home, because she felt “foggy” and more irritable than usual.

As is customary, this busy unit employs nursing preemptive (ie, standing) orders, and the patient was triaged and laboratory tests were drawn including a basic chemistry panel. Upon evaluation by the attending EP, a concern for re-bleed led to a request for a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head, which was interpreted as stable with no new bleed. The case was discussed with the trauma service from the initial hospital and follow-up was arranged.

Prior to the follow-up appointment, the patient returned to the ED because of a further deterioration in mental status. A third head CT was taken and interpreted as stable; however, her serum sodium level was 114 mmol/L. This patient suffered from posttraumatic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), and a retrospective review of the laboratory values from the prior ED visit showed the sodium level to be abnormally low at 121 mmol/L.

This case is a good illustration of “anchoring bias,” in which the existing diagnosis of traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage was maintained as the etiology of the patient’s symptoms, despite a new piece of significant information (ie, the low sodium level) that was not integrated into the differential of possible etiologies for continued deterioration of mental status.

“Anchoring Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Awareness of the power of a prior diagnosis or opinion to mislead is paramount; be sure to carefully review all available data and account for anything that does not lie within the range expected for your diagnosis whenever a patient returns to the ED.

Case Scenario 3: The Search for the Right Piece of the Puzzle

A merchant marine in his mid-40s had fever, jaundice, vomiting, and right upper-quadrant pain for 2 days. He had been airlifted off his ship in the mid-Atlantic Ocean because the medical crew on the ship was concerned that he had a life-threatening illness and they had no surgical facilities available to care for acute cholecystitis with ascending cholangitis.

This patient was otherwise healthy and had all current immunizations. Upon arrival in the ED, he was given intravenous (IV) fluids, antiemetics, and medication for pain control while the workup was underway. He was somnolent and critically ill-appearing. As he spoke only German, a Red Cross interpreter was engaged in an attempt to obtain further information, but the patient was unable to provide additional history. The physician was able to elicit the travel history of the ship by connecting the interpreter with a crewmember on board and learned that the ship was on a return voyage from Haiti, a country endemic with Plasmodium falciparum. It was further determined that this patient was not taking malaria prophylaxis; his blood smear turned out to be positive for the disease.

This case emphasizes the impact of “framing bias” in the thought process that led to the initial diagnosis of ascending cholangitis. Charcot’s Triad of fever, jaundice, and right upper-quadrant pain was the “frame” in which the suspected—yet uncommon—diagnosis was made. The frame of reference, however, changed significantly when the additional information of P. falciparum malaria exposure was elucidated, allowing the correct diagnosis to come into view.

I “Framing Bias” Mitigation Strategy: Confirm that the points of data align properly and fit within the diagnostic possibilities. If they do not connect, seek further information and widen the frame of reference.

Case Scenario 4: Mother Knows Best

The parents of an 11-year-old boy brought their child to the ED for abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that started 10 hours prior to presentation. The boy had no medical or surgical history. During the examination, his mother expressed concern for appendicitis, a common concern of parents whose children have abdominal pain.

Although the boy was uncomfortable, he had no right lower-quadrant tenderness; his bowel sounds were normal, and there was no tenderness to heel tap or Rovsing’s sign. He did have periumbilical tenderness and distractible guarding. His white blood-cell (WBC) count was 12.5 K/uL with 78% segmented neutrophils and urinalysis showed 15 WBCs/hpf with no bacteria. With IV hydration, opioid pain medication, and antiemetic medication, the patient felt much better, and the abdominal examination improved with no tenderness.

After a clear liquid trial was successful, careful counseling of the parents made it clear that appendicitis was possible, but unlikely given the improvement in symptoms, and the boy was discharged with the diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis. Six hours later, the boy was brought back to the ED and then taken to the operating room for acute appendicitis.

This case illustrates the effect of “confirmation bias,” in which the preference to favor a particular diagnosis outweighs the clinical clues that suggested the correct diagnosis. Neither possible opioid effect in masking pain nor the lack of history or complaint of diarrhea was effectively taken into consideration before making the diagnosis of “gastroenteritis.”

I “Confirmation Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Be aware that selective filtering of information to confirm a belief is wrought with danger. Seek data and information that could weaken or negate the belief and give it serious consideration.

Case Scenario 5: The “Frequent Flyer”

This case involved an extremely difficult-to-manage patient who had presented to the ED many times in the past with “the worst headache of his life.” During these visits, he was typically disruptive, problematic to discharge safely, and a particular behavioral issue for the nurses. As a result, when he presented to the ED, the goal was to evaluate him quickly, treat him humanely, and diagnose and discharge him as soon as possible. He was never accompanied by family or friends. His personal medical history was positive for uncontrolled hypertension and chronic alcoholism.

Attempts to coordinate his care with social services and community mental health were unsuccessful. On examination, his blood pressure was 210/105 mm Hg and a severe headache was once again his chief complaint. A head CT scan performed less than 12 hours prior to this presentation revealed no new findings compared with many prior CTs. However, there was a slight slurring of his speech on this visit that wasn’t part of his prior presentations. After he was given lorazepam and a meal tray, the patient felt a little better and was discharged. The patient never returned to the ED, and the staff has since become concerned that on this last ED visit, their “frequent flyer” had something real.

Although it is not known what exactly happened to this patient, the manner in which he was treated represents the effect of premature closure on the medical decision-making process. When a clinician jumps to conclusions without seeking more information, the possibility of an error in judgment exists.

I “Premature Closure” Mitigating Strategies: Never stop thinking even after a conclusion has been reached. Instead, stop and think again about what else could be happening.

Conclusion

In all of the case scenarios presented, any or all of the patients might have survived the errors made without any adverse outcome, but the errors might also have resulted in mild to severe permanent disability or death. It is important to remember that errors can happen regardless of good intentions and acceptable practice, and that although an error may have no consequence in one set of circumstances, the same error could be deadly in others.

On the systems level, approaches to assess and control the work environment are necessary to mitigate risk to individuals, create a culture of safety, and encourage collective learning and continuous improvement. Recognition of the frequent incidence of error and awareness of the overlapping cognitive biases (Table), while always being mindful to take a moment to think further, can help avoid—but never eliminate--these types of mistakes.

Dr McCammon is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

- Gawande A. Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance. New York, NY: Picador; 2007.

- National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Emergency Department Summary

- Tables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2010_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a safer health system. https://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf. Published November 1999. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- James, JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Pat Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128.

- Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61(6):1-51. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_06.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- Wellbury C. Flaws in clinical reasoning: a common cause of diagnostic error. Am Fam Physician. 2011; 84(9):1042-1048

- Gawande A. Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance. New York, NY: Picador; 2007.

- National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Emergency Department Summary

- Tables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2010_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a safer health system. https://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf. Published November 1999. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- James, JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Pat Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128.

- Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61(6):1-51. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_06.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- Wellbury C. Flaws in clinical reasoning: a common cause of diagnostic error. Am Fam Physician. 2011; 84(9):1042-1048