User login

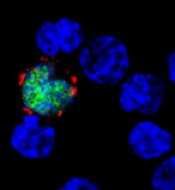

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of

Benjamin Chaigne-Delalande

New research published in Nature Communications appears to explain how Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reprograms cells into cancer cells.

Investigators said they discovered a mechanism by which EBV particles induce chromosomal instability without establishing a chronic infection, thereby conferring a risk for the development of tumors that do not necessarily carry the viral genome.

“The contribution of the viral infection to cancer development in patients with a weakened immune system is well understood,” said study author Henri-Jacques Delecluse, MD, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

“But in the majority of cases, it remains unclear how an EBV infection leads to cancer development.”

With their research, Dr Delecluse and his colleagues found that BNRF1, a protein component of EBV, promotes the development of cancer. They said BNRF1 induces centrosome amplification, which is associated with chromosomal instability.

When a dividing cell comes in contact with EBV, BNRF1 frequently prompts the formation of an excessive number of centrosomes. As a result, chromosomes are no longer divided equally and accurately between daughter cells—a known cancer risk factor.

In contrast, when the investigators studied EBV deficient of BNRF1, they found the virus did not interfere with chromosome distribution to daughter cells.

The team noted that EBV normally remains silent in a few infected cells, but, occasionally, it reactivates to produce viral offspring that infects nearby cells. As a consequence, these cells come in close contact with BNRF1, thus increasing their risk of transforming into cancer cells.

“The novelty of our work is that we have uncovered a component of the viral particle as a cancer driver,” Dr Delecluse said. “All human-tumors viruses that have been studied so far cause cancer in a completely different manner.”

“Usually, the genetic material of the viruses needs to be permanently present in the infected cell, thus causing the activation of one or several viral genes that cause cancer development. However, these gene products are not present in the infectious particle itself.”

Dr Delecluse and his colleagues therefore suspect that EBV could cause cancers other than those that have already been linked to EBV. Certain cancers might not have been linked to the virus because they do not carry the viral genetic material.

“We must push forward with the development of a vaccine against EBV infection,” Dr Delecluse said. “This would be the most direct strategy to prevent an infection with the virus.”

“Our latest results show that the first infection could already be a cancer risk, and this fits with earlier work that showed an increase in the incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in people who underwent an episode of infectious mononucleosis.” ![]()

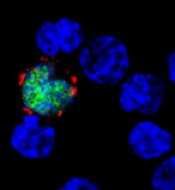

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of

Benjamin Chaigne-Delalande

New research published in Nature Communications appears to explain how Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reprograms cells into cancer cells.

Investigators said they discovered a mechanism by which EBV particles induce chromosomal instability without establishing a chronic infection, thereby conferring a risk for the development of tumors that do not necessarily carry the viral genome.

“The contribution of the viral infection to cancer development in patients with a weakened immune system is well understood,” said study author Henri-Jacques Delecluse, MD, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

“But in the majority of cases, it remains unclear how an EBV infection leads to cancer development.”

With their research, Dr Delecluse and his colleagues found that BNRF1, a protein component of EBV, promotes the development of cancer. They said BNRF1 induces centrosome amplification, which is associated with chromosomal instability.

When a dividing cell comes in contact with EBV, BNRF1 frequently prompts the formation of an excessive number of centrosomes. As a result, chromosomes are no longer divided equally and accurately between daughter cells—a known cancer risk factor.

In contrast, when the investigators studied EBV deficient of BNRF1, they found the virus did not interfere with chromosome distribution to daughter cells.

The team noted that EBV normally remains silent in a few infected cells, but, occasionally, it reactivates to produce viral offspring that infects nearby cells. As a consequence, these cells come in close contact with BNRF1, thus increasing their risk of transforming into cancer cells.

“The novelty of our work is that we have uncovered a component of the viral particle as a cancer driver,” Dr Delecluse said. “All human-tumors viruses that have been studied so far cause cancer in a completely different manner.”

“Usually, the genetic material of the viruses needs to be permanently present in the infected cell, thus causing the activation of one or several viral genes that cause cancer development. However, these gene products are not present in the infectious particle itself.”

Dr Delecluse and his colleagues therefore suspect that EBV could cause cancers other than those that have already been linked to EBV. Certain cancers might not have been linked to the virus because they do not carry the viral genetic material.

“We must push forward with the development of a vaccine against EBV infection,” Dr Delecluse said. “This would be the most direct strategy to prevent an infection with the virus.”

“Our latest results show that the first infection could already be a cancer risk, and this fits with earlier work that showed an increase in the incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in people who underwent an episode of infectious mononucleosis.” ![]()

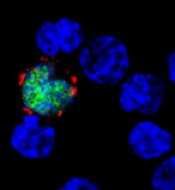

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of

Benjamin Chaigne-Delalande

New research published in Nature Communications appears to explain how Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reprograms cells into cancer cells.

Investigators said they discovered a mechanism by which EBV particles induce chromosomal instability without establishing a chronic infection, thereby conferring a risk for the development of tumors that do not necessarily carry the viral genome.

“The contribution of the viral infection to cancer development in patients with a weakened immune system is well understood,” said study author Henri-Jacques Delecluse, MD, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

“But in the majority of cases, it remains unclear how an EBV infection leads to cancer development.”

With their research, Dr Delecluse and his colleagues found that BNRF1, a protein component of EBV, promotes the development of cancer. They said BNRF1 induces centrosome amplification, which is associated with chromosomal instability.

When a dividing cell comes in contact with EBV, BNRF1 frequently prompts the formation of an excessive number of centrosomes. As a result, chromosomes are no longer divided equally and accurately between daughter cells—a known cancer risk factor.

In contrast, when the investigators studied EBV deficient of BNRF1, they found the virus did not interfere with chromosome distribution to daughter cells.

The team noted that EBV normally remains silent in a few infected cells, but, occasionally, it reactivates to produce viral offspring that infects nearby cells. As a consequence, these cells come in close contact with BNRF1, thus increasing their risk of transforming into cancer cells.

“The novelty of our work is that we have uncovered a component of the viral particle as a cancer driver,” Dr Delecluse said. “All human-tumors viruses that have been studied so far cause cancer in a completely different manner.”

“Usually, the genetic material of the viruses needs to be permanently present in the infected cell, thus causing the activation of one or several viral genes that cause cancer development. However, these gene products are not present in the infectious particle itself.”

Dr Delecluse and his colleagues therefore suspect that EBV could cause cancers other than those that have already been linked to EBV. Certain cancers might not have been linked to the virus because they do not carry the viral genetic material.

“We must push forward with the development of a vaccine against EBV infection,” Dr Delecluse said. “This would be the most direct strategy to prevent an infection with the virus.”

“Our latest results show that the first infection could already be a cancer risk, and this fits with earlier work that showed an increase in the incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in people who underwent an episode of infectious mononucleosis.” ![]()