User login

Shared decision-making (SDM), a methodology for improving patient communication, education, and outcomes in preference-sensitive health care decisions, debuted in 1989 with the Ottawa Decision Support Framework1 and the creation of the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (now the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation).2 SDM enhances care by actively involving patients as partners in their health care choices. This approach can not only increase patient knowledge and satisfaction with care but also has a beneficial effect on adherence and outcomes.3-5

Despite the significant benefits of SDM, overall uptake of SDM practices remains low—even in situations in which SDM is a requirement for reimbursement, such as in lung cancer screening.6-8 The ever-shifting list of conditions that warrant the implementation of SDM in a family practice can be daunting. Our review seeks to highlight current best practices, review common situations in which SDM would be beneficial, and describe tools and frameworks that can facilitate effective SDM conversations in the typical primary care practice.

Preference-sensitive care

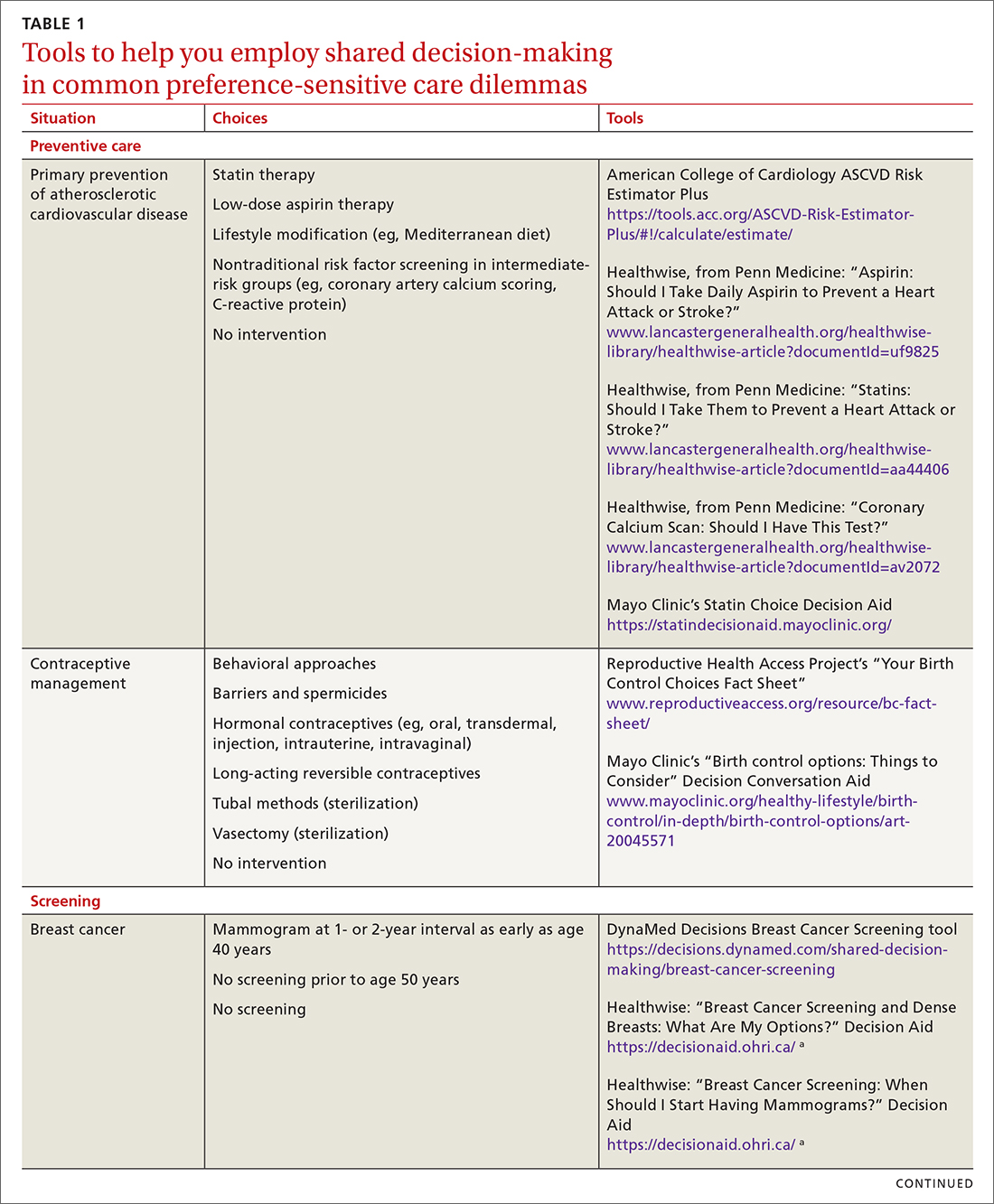

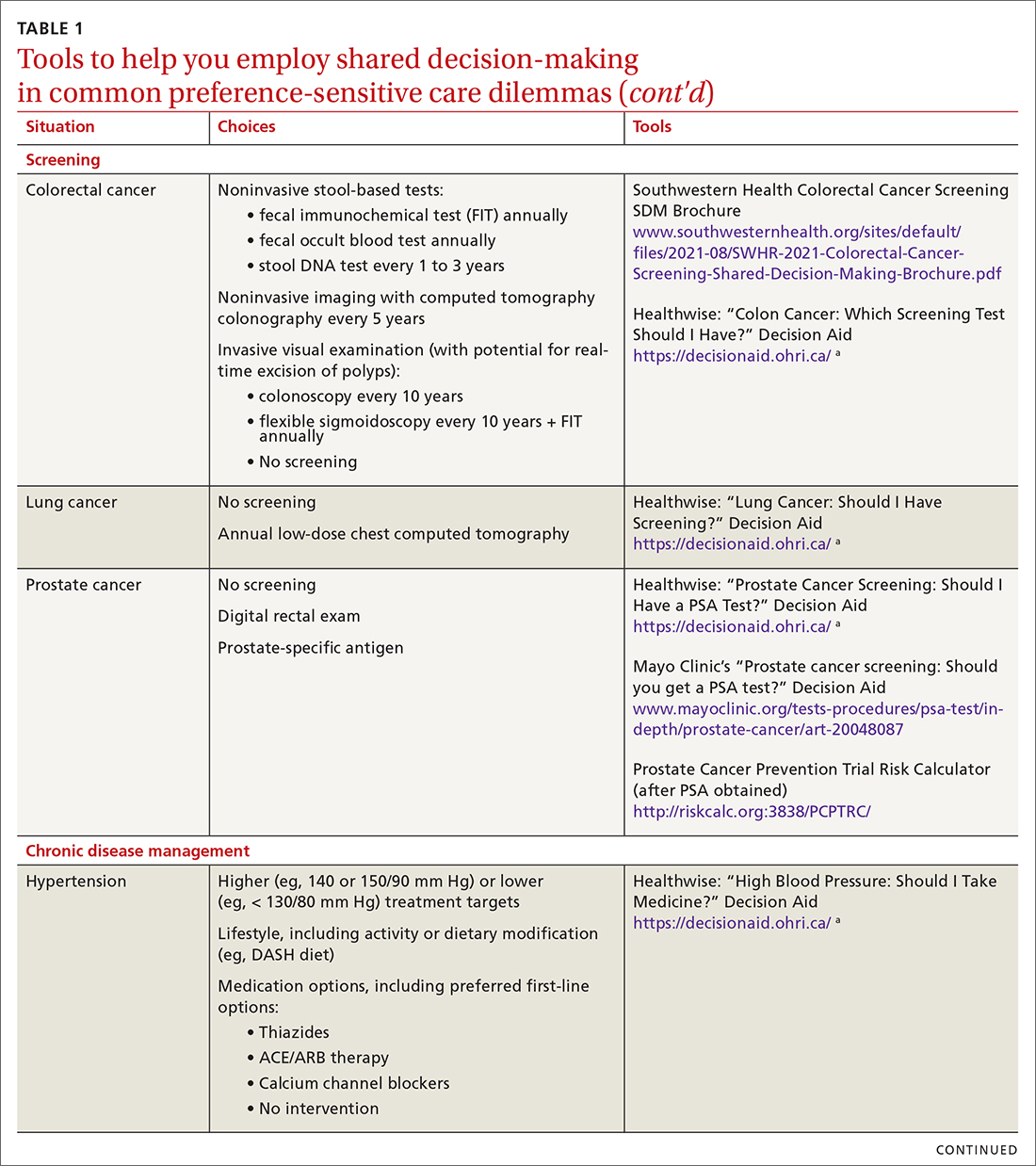

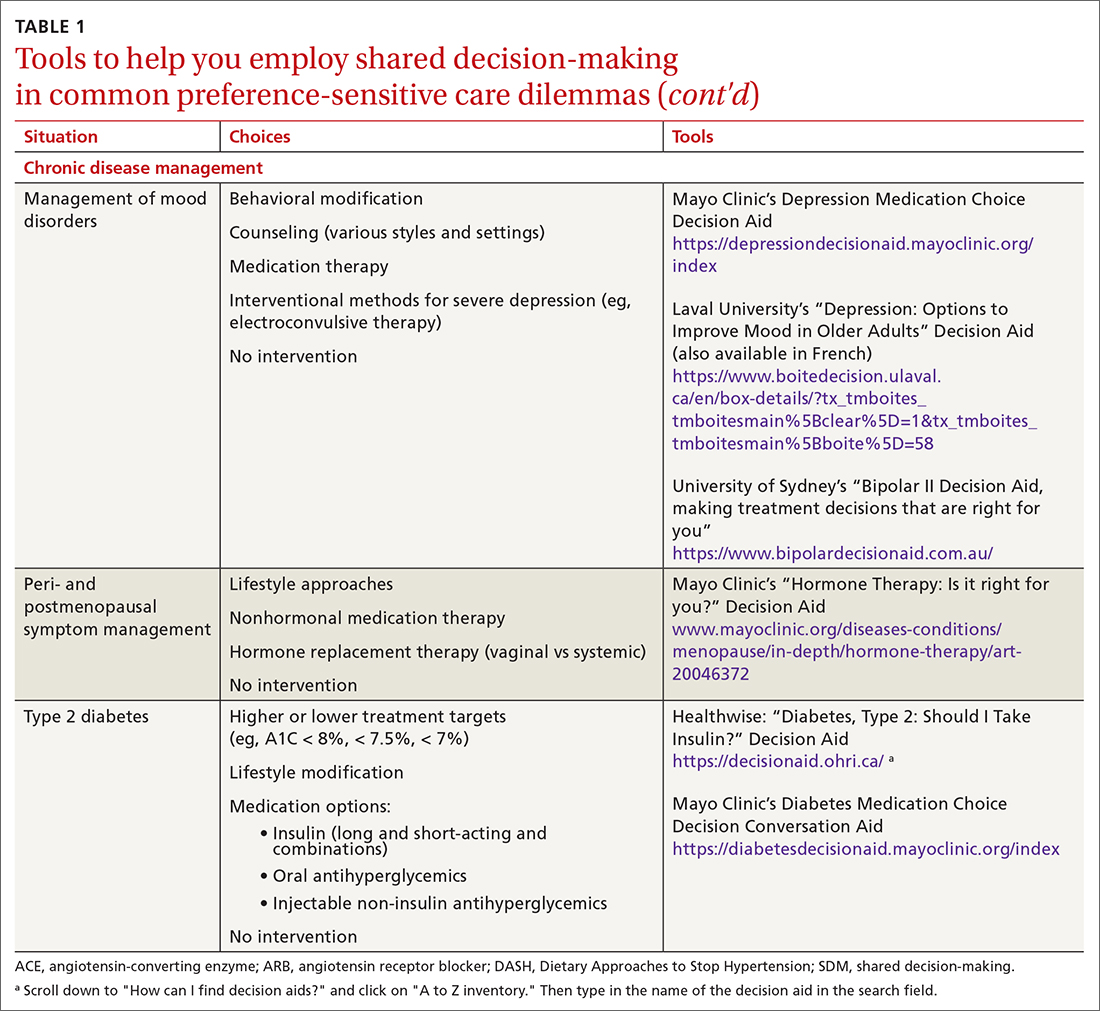

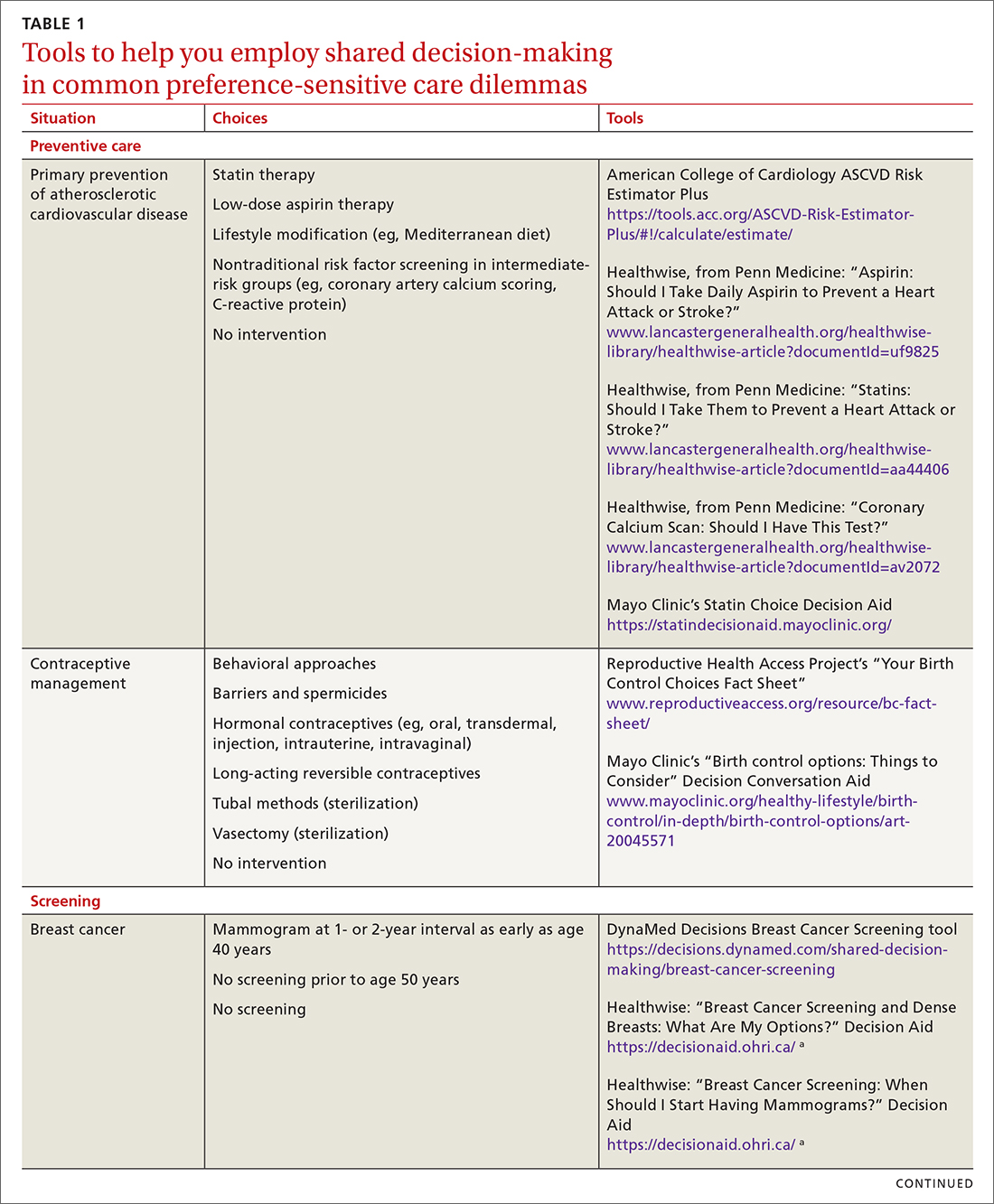

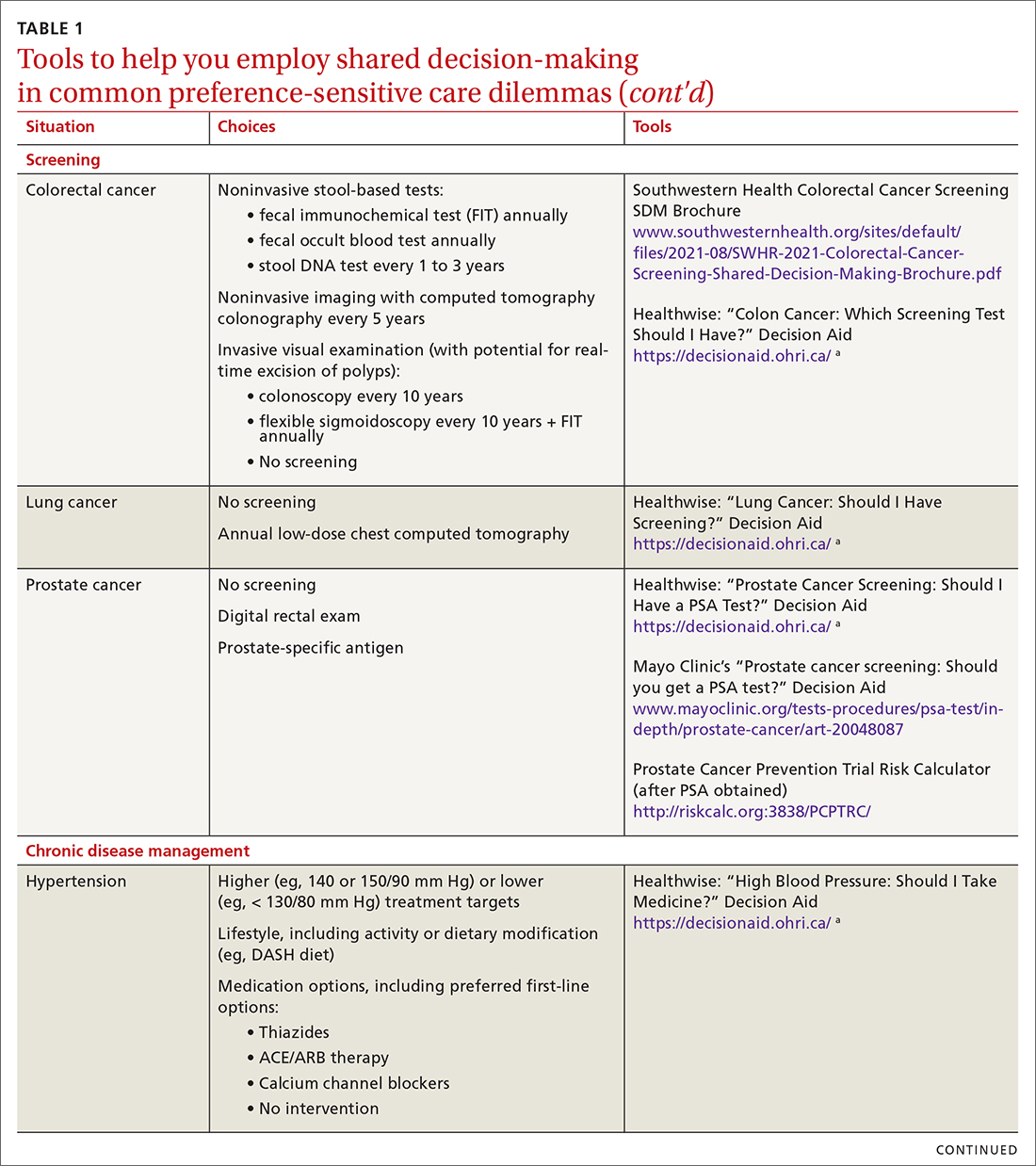

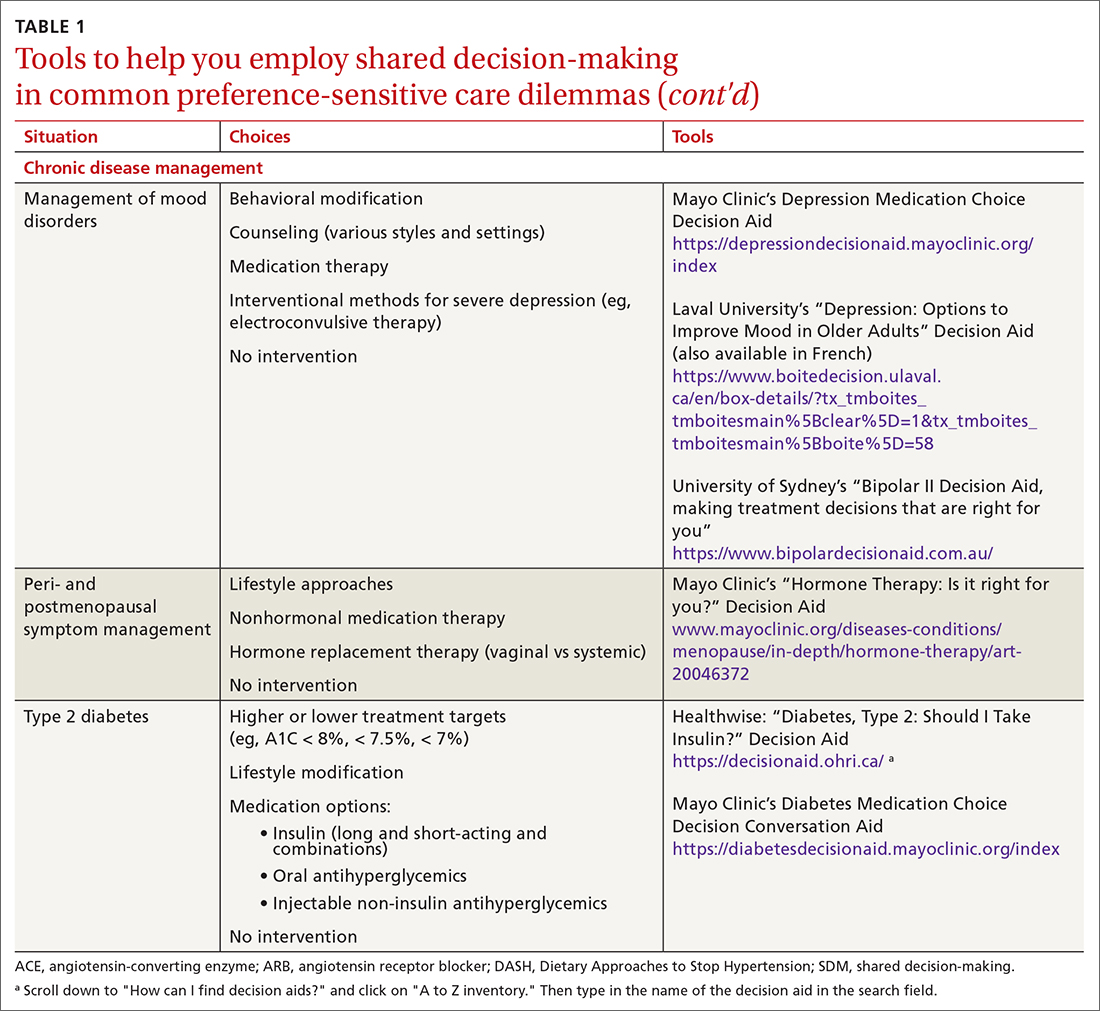

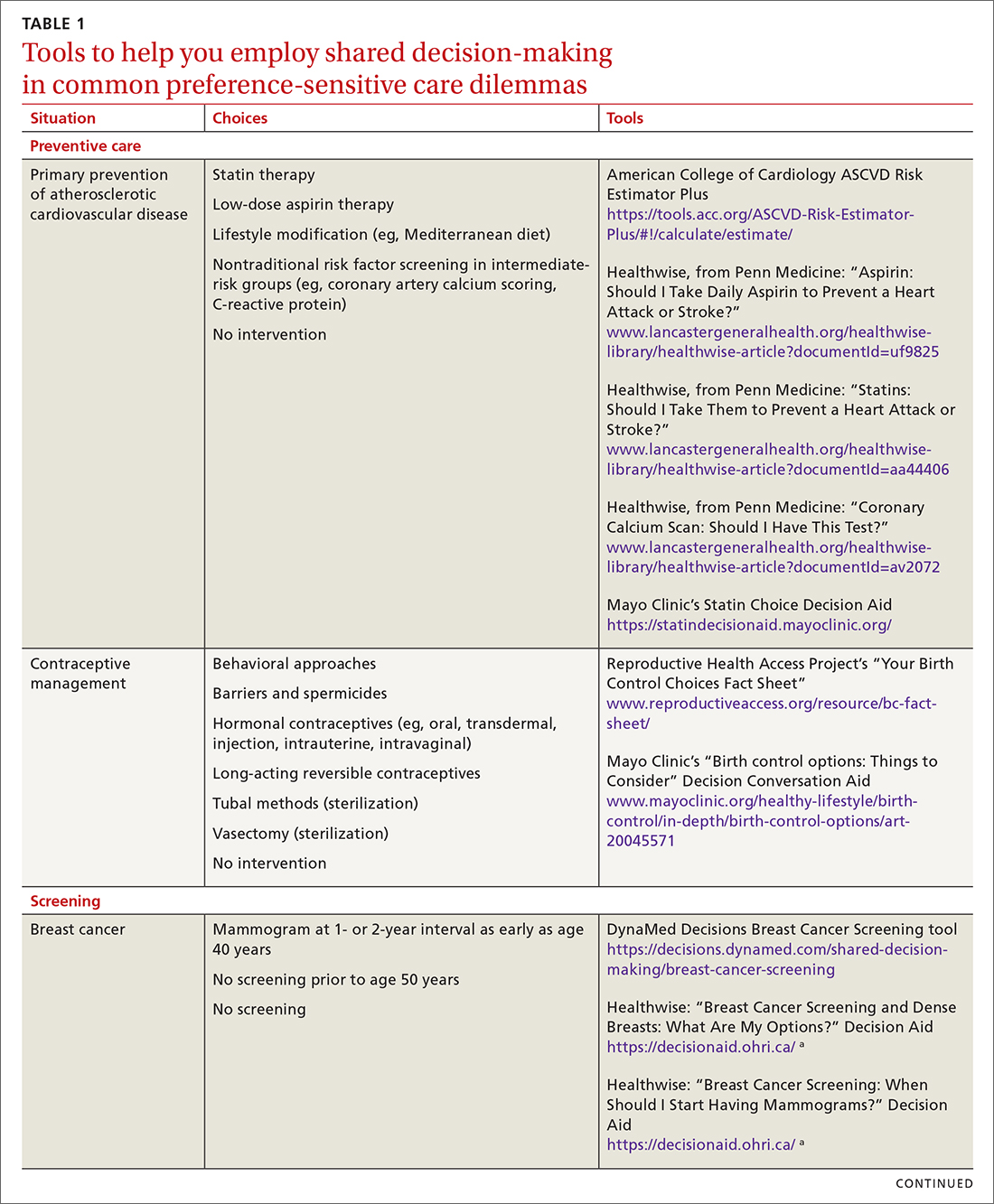

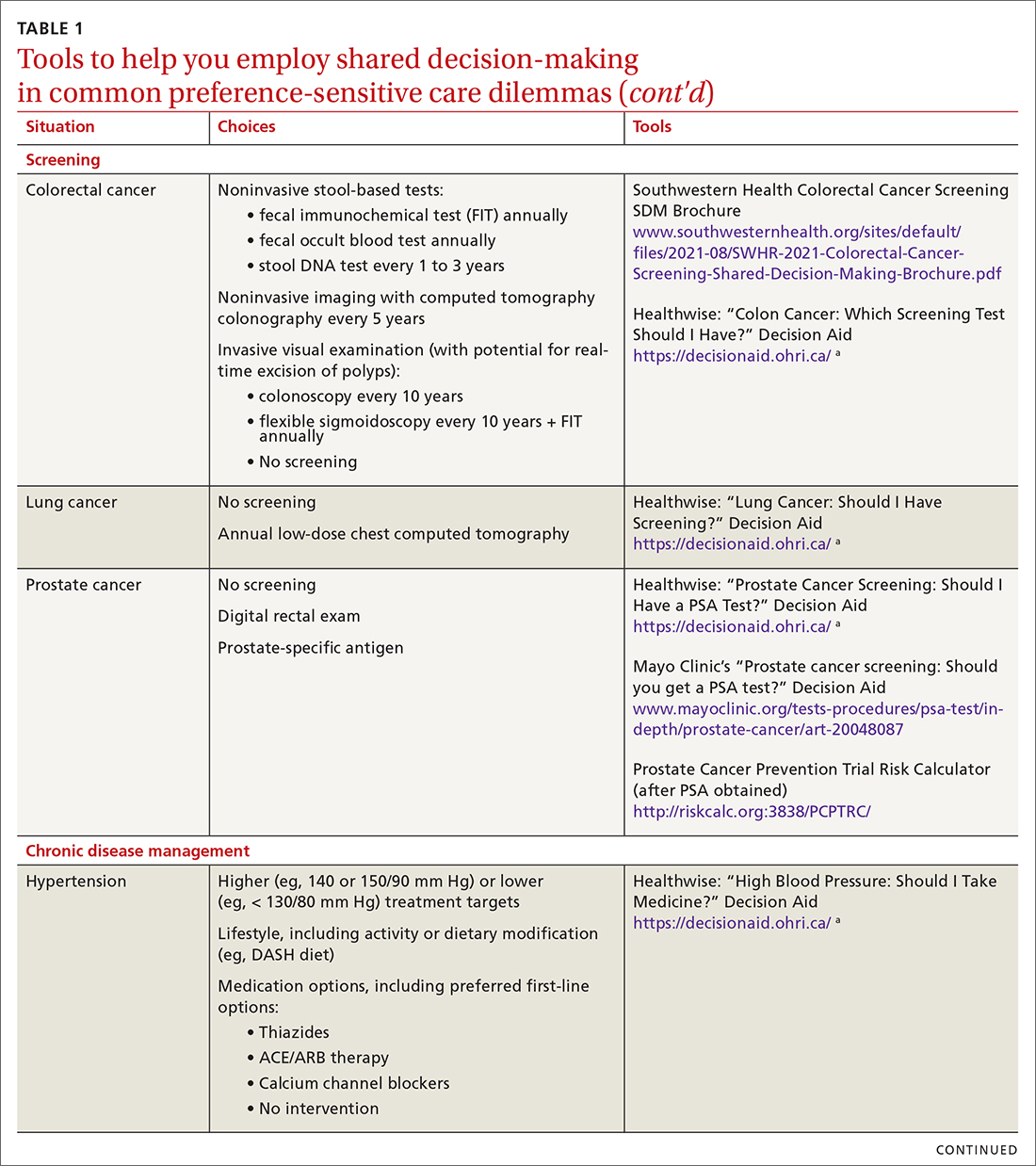

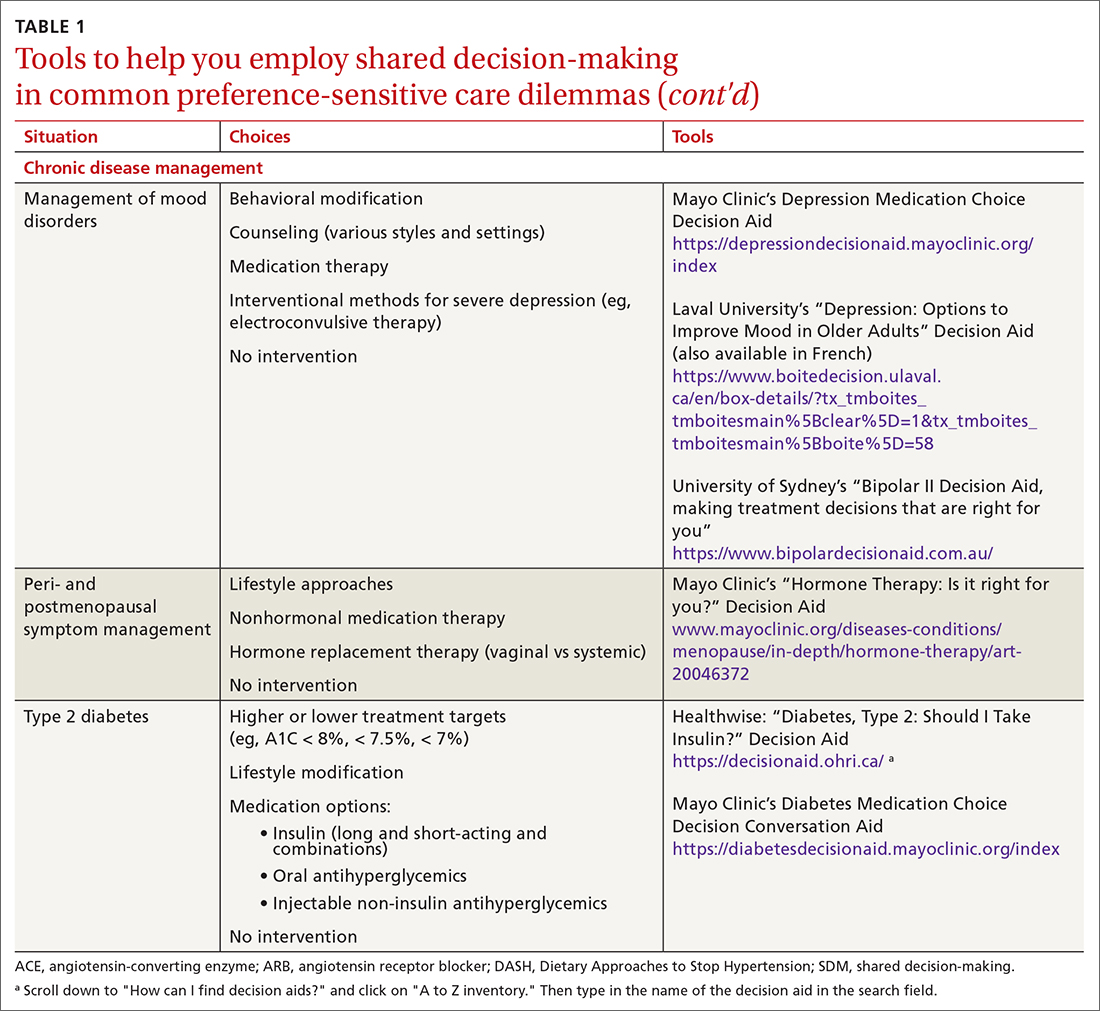

SDM is designed to enhance the role of patient preference, considering a patient’s own personal values for managing clinical conditions when more than one reasonable strategy exists. Such situations are often referred to as preference-sensitive conditions—ie, since evidence is limited on a single “best” treatment approach, patients’ values should impact decision-making.9 Examples of common preference-sensitive situations that include preventive care, screening, and chronic disease management are outlined in TABLE 1.

How to engage patients

In preference-sensitive care situations, SDM endeavors to address uncertainty by laying out what the options are, as well as providing risk and benefit data. This helps inform patients and guides providers about individual patient preference on whether to screen (eg, for average-risk female patients, breast cancer screening between ages 40-50 years). SDM can assist with determining whether to screen and if so, at what interval (eg, at 1- or 2-year intervals), while acknowledging that no single decision would be “best” for every patient.

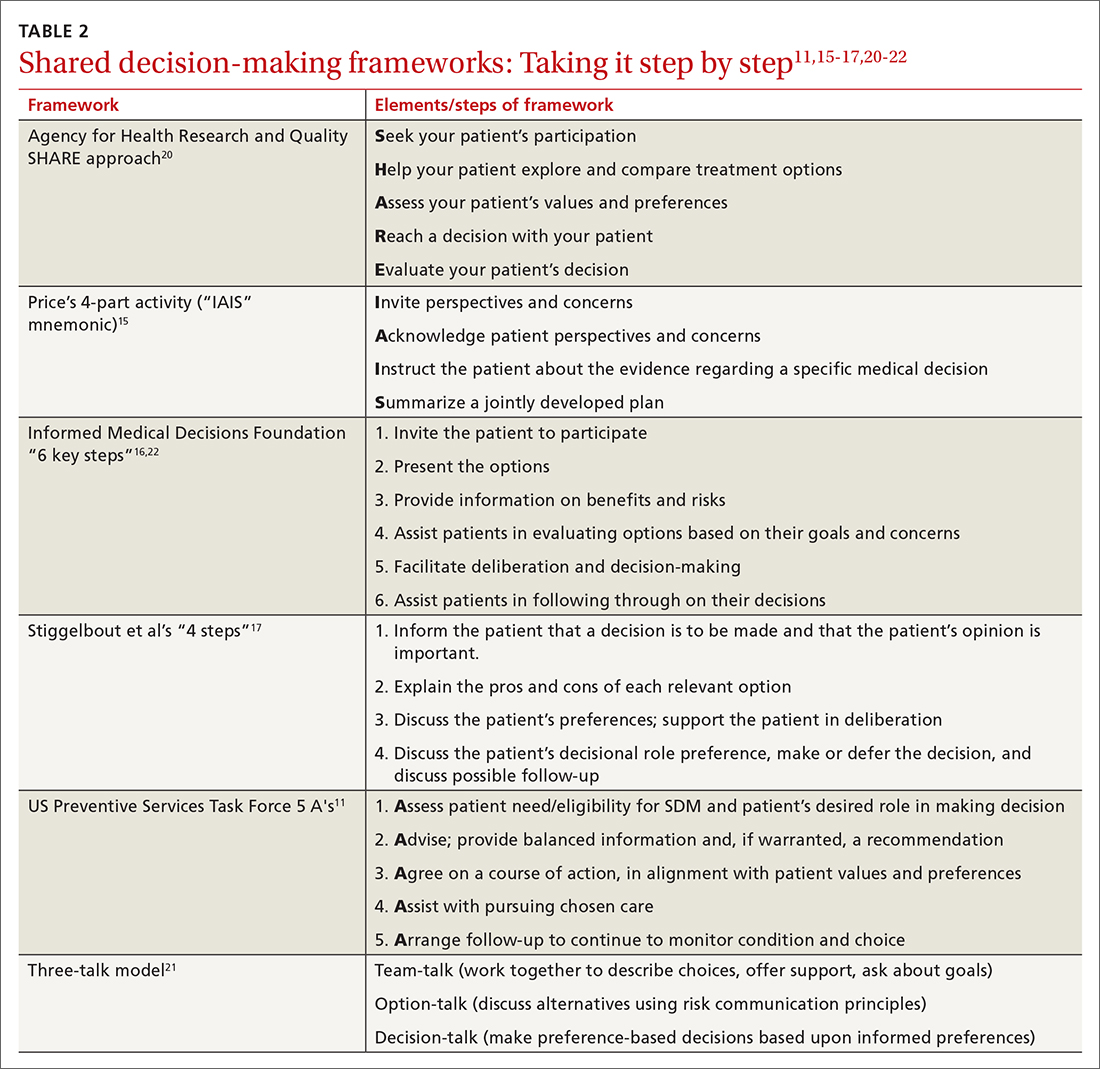

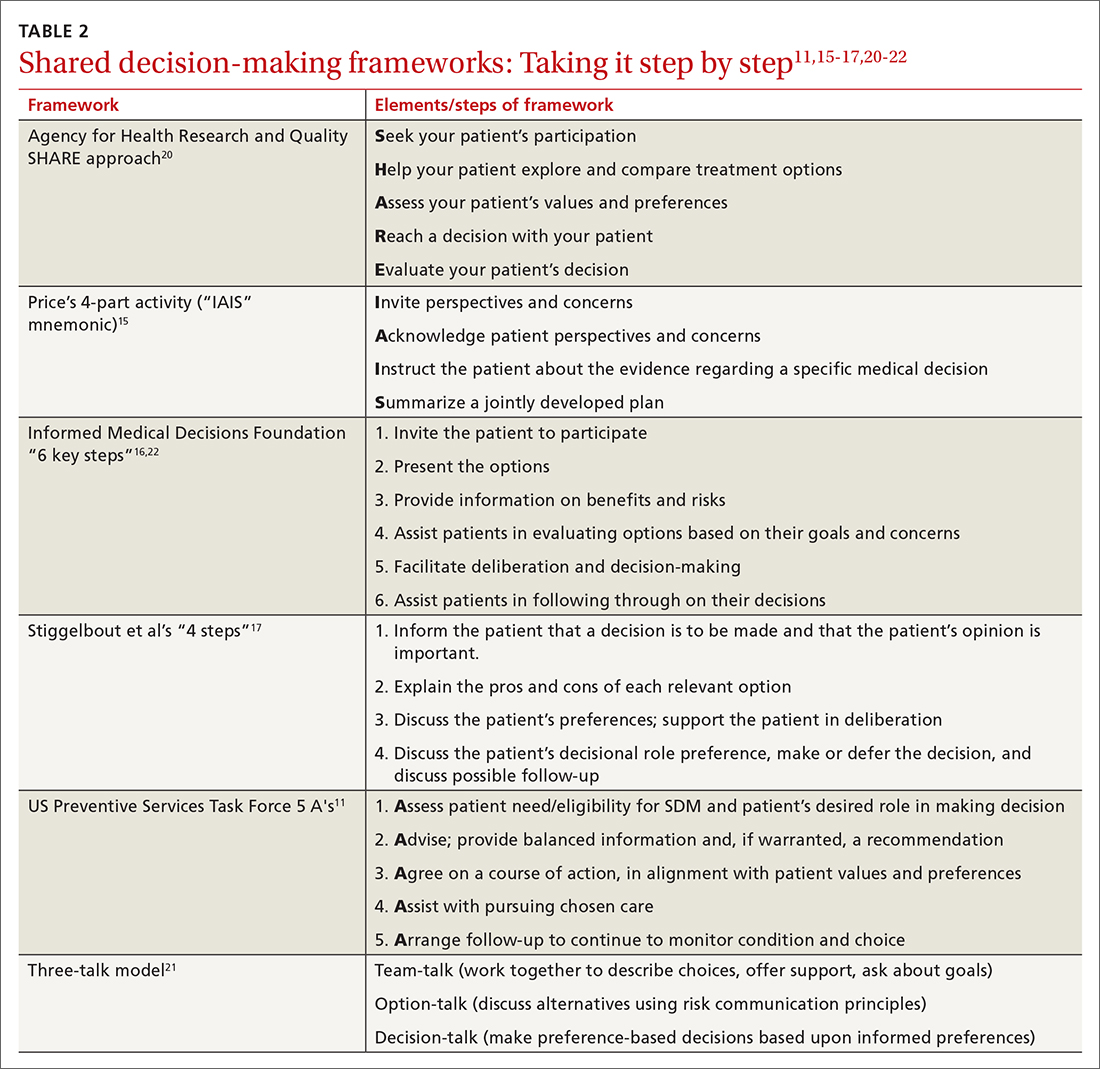

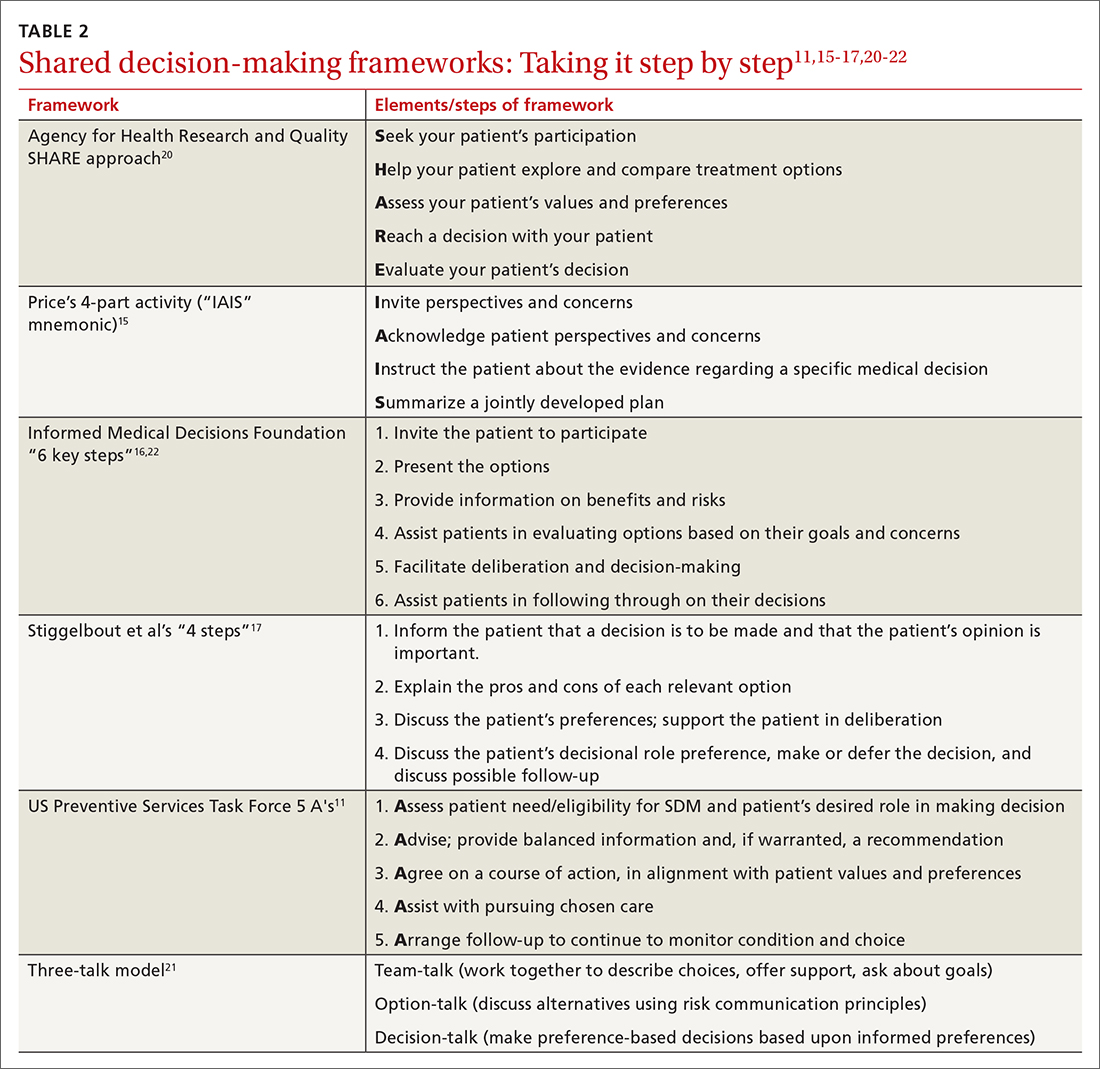

While there are formalized tools to provide information to patients and help them consider their values and choices,3,10 SDM does not hinge on the use of an explicit tool.11-18 There are many approaches to and interpretations of SDM; the Ottawa Decision Support Framework reviews and details these many considerations at length in its 2020 revision.19 TABLE 211,15-17,20-22 highlights various SDM frameworks and the steps involved.

These 3 elements are commonamong SDM frameworks

In a 2019 systematic review, the following 3 elements were highlighted as the most prevalent over time across SDM frameworks and could be considered core to any meaningful SDM process23:

Explicit effort by 2 or more experts. The patient is an expert in their own values. The clinician, as an expert in relevant medical knowledge, clarifies that the current medical situation will benefit from incorporating the patient’s preferences to arrive at an appropriate shared decision.

Continue to: Effort to provide relevant...

Effort to provide relevant, evidence-based information. The clinician provides treatment options applicable to the patient, including the risks and benefits of each (potentially using one of the decision aids in the following section), to facilitate a values-based discussion and decision.

Patient support and assistance. The clinician assists the patient in navigating next steps based on the treatment decision and arranges necessary follow-up.

Various case studies and examples of SDM conversations have been published.15-17,24 Video examples of optimal25 and less than optimal26 SDM conversations are available on the Massachusetts General Hospital Health Decision Sciences Center website (https://mghdecisionsciences.org/) under the section “Tools & Training >> Videos about Shared Decision-Making.”27

SDM and motivational interviewing: Both can serve you well

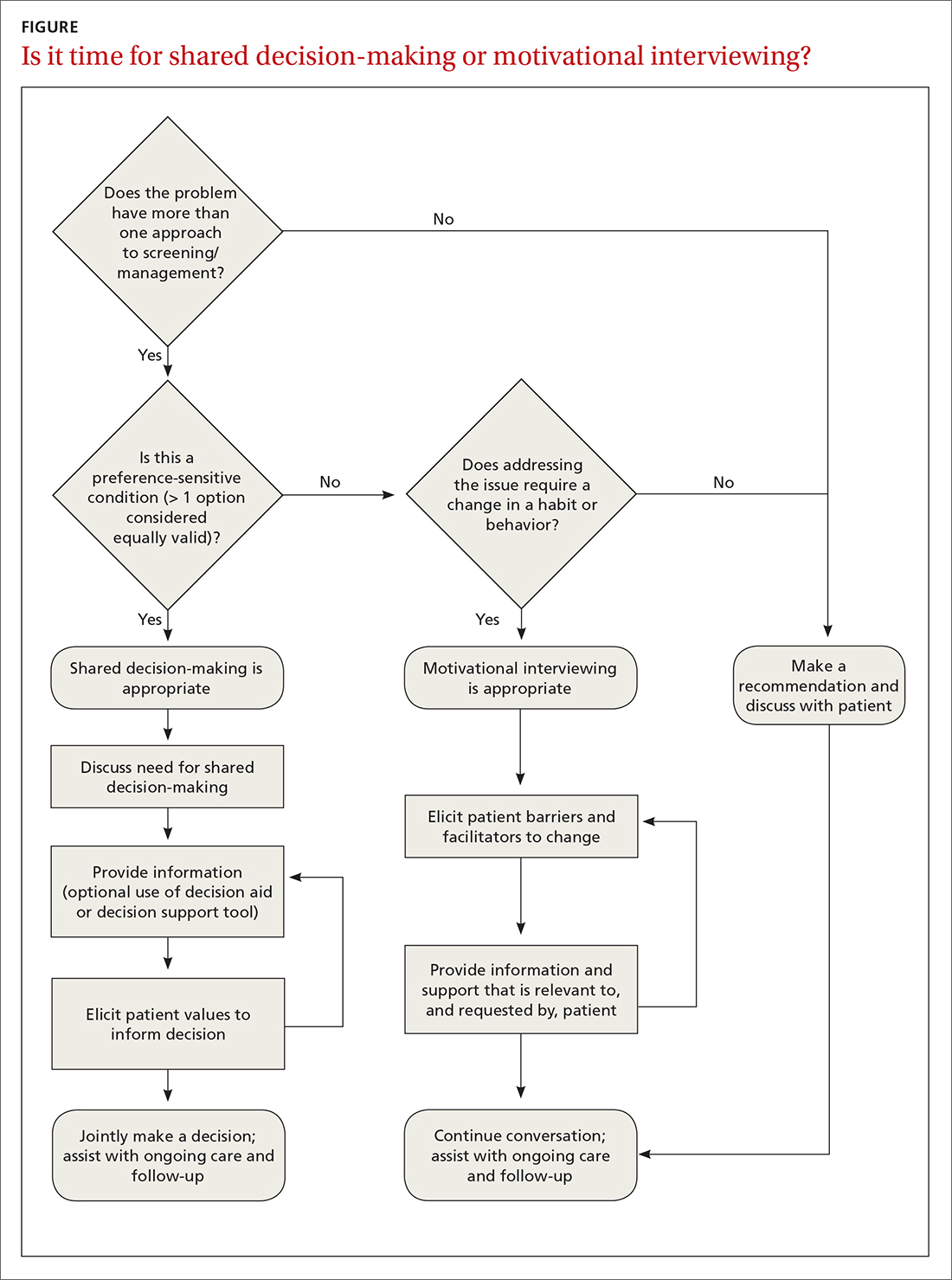

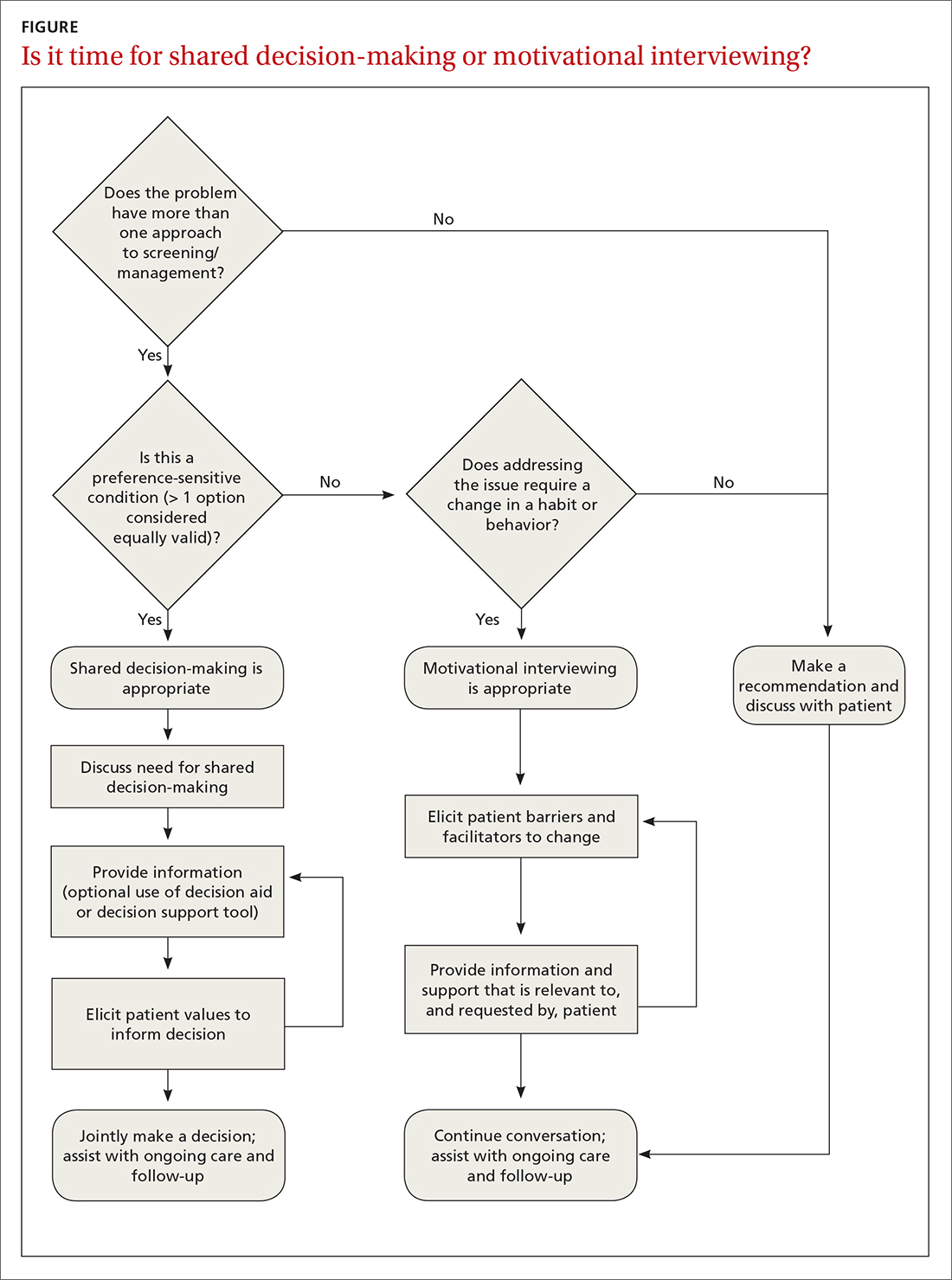

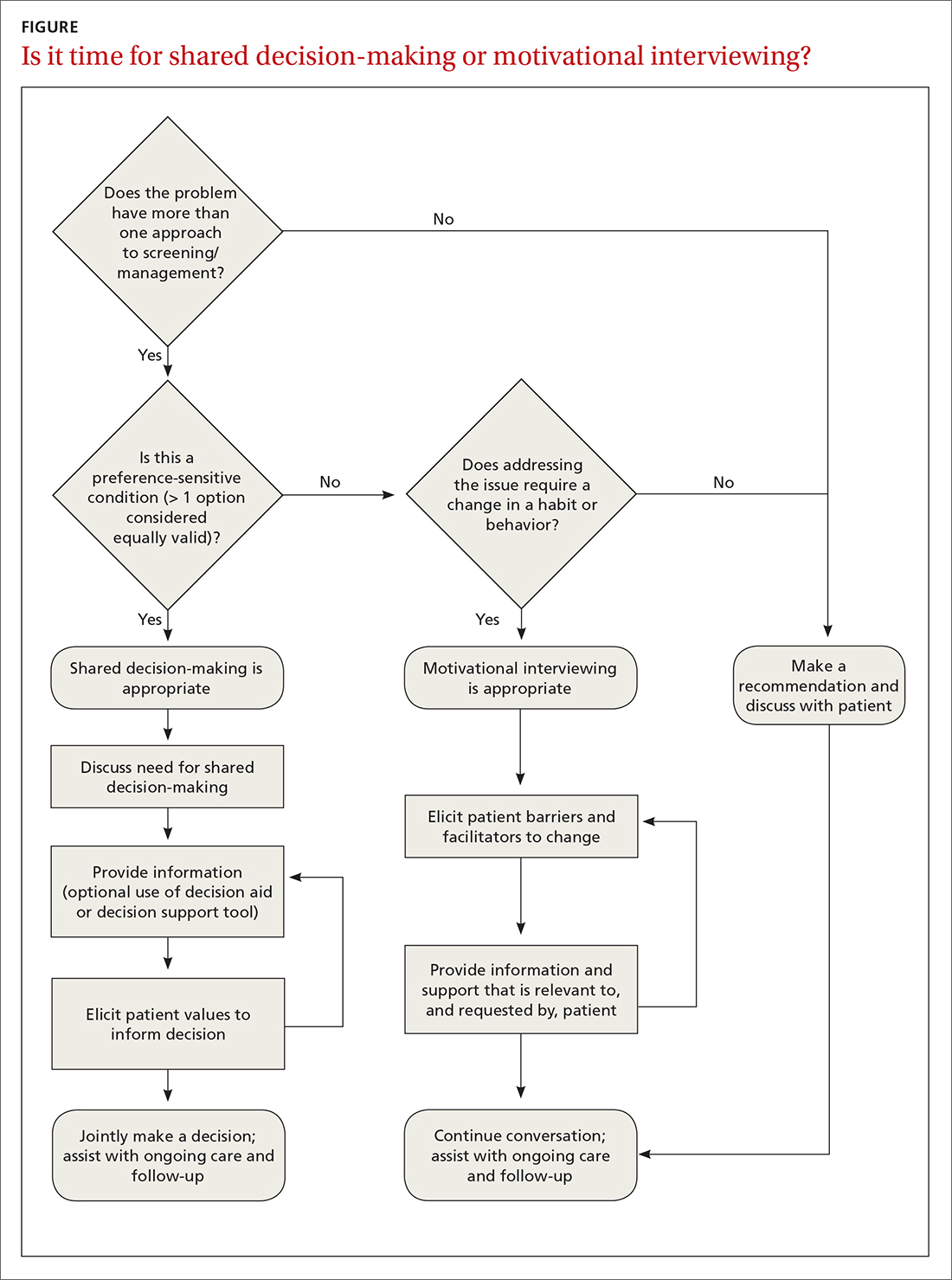

SDM and motivational interviewing share many common elements,28 and it’s useful to take advantage of both techniques. Preference-sensitive care situations may require a combination of approaches.

For example, motivational interviewing may be a beneficial tool when dealing with a patient who is initially against colon cancer screening (evidence clearly favors screening in some form over no screening) and has a history of avoiding medical care. Through an SDM approach, motivational interviewing may identify an opportunity to prioritize the patient’s preference to minimize medical intervention by ensuring that the patient is familiar with noninvasive colon cancer screening options. After sufficiently eliciting a patient value aligned with screening and engaging the patient’s own motivations for follow-through, a more thorough SDM conversation can then help clarify the best options.

Continue to: A proposed framework...

A proposed framework for identifying whether SDM or motivational interviewing is appropriate is featured in the FIGURE. In their paper, Elwyn et al29 further define and discuss the distinguishing features and roles of SDM and behavioral support interventions, such as motivational interviewing.

Tools to facilitate SDM conversations

Decision aids

SDM has historically been operationalized for study through the use of decision aids: formally structured materials describing, in detail, the available treatment options under consideration, including the relative risks and benefits. Frequently, such tools are framed from a patient perspective, with digestible information presented in a multimedia format (eg, visual risk representations of “1 out of 10” in an icon array vs “10%”), leveraging effective risk communication strategies (eg, absolute risk rates vs relative risks and “balanced framing”). For instance, the physician would note that 1 out of 10 patients have an outcome and 9 out of 10 do not.

Additional information on risk communication skills is available at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s webpage on the SHARE approach (www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/tool/resource-5.html).30 Decision aids have been shown to enhance health literacy, increase patient knowledge and understanding, and promote the frequency of “values-concordant” choices.3

Point-of-care decision support

A more recent trend in SDM is increased development and use of point-of-care decision support tools that emphasize information reflecting individual patient circumstances (eg, leveraging heart risk calculators to individualize risk conversations when considering statins for primary prevention of heart disease based on lipids and other demographic factors). An advantage to using such tools is that they provide “just-in-time” detailed and personalized evidence-based information, guiding the discussion and minimizing the need for an extensive advance review of each topic by emphasizing the “key facts.” To ensure effective use of SDM tools, avoid oversaturating patients with data, maintain a focus on patient values, and engage in a 2-way discussion that considers the unique mix of preferences and circumstances.

Proprietorship of tools and decision aids

Until recently, SDM materials were compiled primarily within not-for-profit entities such as the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, which became a division of Healthwise in 2014.2 In recent years, there has been an increasing trend of for-profit companies acquiring or developing their own decision aids and decision-support tools, eg, EBSCO Health (Option Grid31 and Health Decision32) and Wolters Kluwer (EMMI33). The extensive work of curating SDM and educational tools to keep up with best medical evidence is costly, and the effort to defray costs can give rise to potential conflicts of interest. Therefore, the interests of the creators of such tools—whether commercial or academic—should always be considered when evaluating the use of a given decision-support tool.

Contunue to: An online listing...

An online listing of publicly available decision aids is maintained by the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute,34 which reviews decision-aid quality by objective criteria in addition to providing direct links to resources.35 EBSCO health’s DynaMed Decisions also maintains a list of shared decision-making tools (https://decisions.dynamed.com/).

Effectiveness of decision aids

There is a robust body of research focused on decision aids for SDM. An example is a 2017 Cochrane review that concluded SDM facilitated by decision aids significantly improved patient engagement and satisfaction and increased patient knowledge, accuracy in risk perception, and congruency in making value-aligned care choices. Beyond decision aids, studies show SDM practices increase patient knowledge, engagement, and satisfaction, particularly among low-literacy or disadvantaged groups.4,36,37

Barriers to implementation

Clinicians frequently cite time constraints as a barrier to successfully implementing SDM in practice, although studies that explicitly compare the time/cost of SDM to “usual care” are limited.38 A Cochrane review of 105 studies evaluating the use of decision aids vs usual care found that only 10 studies examined the effects of decision aids on the length of the office visit.3 Two of these studies (one evaluating decision aids for prenatal diagnostic screening and the other for atrial fibrillation) found a median increase in visit length of 2.6 minutes (24 vs 21; 7.5% increase); the other 8 studies reported no increase in visit length.3

Studies focusing on the time impact of using SDM in an office visit, rather than decision aids as a proxy for SDM, are few. A study by Braddock et al39 assessed the elements of SDM, measuring the quality and the time-efficiency of 141 surgical decision-making interactions between patients and 89 orthopedic surgeons. Researchers found 57% of the discussions had elements of SDM sufficient to meet a “reasonable minimum” standard (eg, nature of the decision, patient’s role, patient’s preference). These conversations took 20 minutes compared to a median of 16 minutes for a more typical conversation.39 The study used audiotaped interviews, which were coded and scored based on the presence of SDM elements; treatment choice, outcomes of the choices, and satisfaction were not reported. A separate study by Loh et al5 looking at SDM in primary care for patients with depression sought to determine whether patient participation in the decision-making process improved treatment adherence, outcomes, and patient satisfaction without increasing consultation time. This study, which included 23 physicians and 405 patients, found improved participation and satisfaction outcomes in the intervention group and no difference in consultation time between the intervention and control groups.5

Care costs appear similar

The impact of SDM on cost and patient-centered clinical outcomes is not well defined. One study by Arterburn et al40 found decision aids and SDM lowered the rates of elective surgery for hip and knee arthritis, as well as associated health system costs. However, other studies suggest this phenomenon likely varies by demographic, demonstrating that certain populations with a generally lower baseline preference for surgery on average chose surgery more often after SDM interventions.41,42 Evidence does support patient acceptability and efficacy for SDM in longitudinal care when the approach is incorporated into decisions over multiple visits or long-term decisions for chronic conditions.4 Studies comparing patient groups receiving decision aids to usual care have shown similar or lower overall care costs for the decision-aid group.3

Continue to: Limitations to the evidence

Limitations to the evidence

Systematic reviews routinely note substantial heterogeneity in the literature on SDM use, owing to variable definitions of what steps are essential to constitute an SDM intervention and a wide variety of outcome measures used, as well as the broad range of conditions to which SDM is potentially applicable.3,4,10,36,37,43-45 While efforts in SDM education, uptake, and study frequently adapt frameworks such as those outlined in TABLE 2,11,15-17,20-22 there is as yet no one consensus on the “best” approach to SDM, and explicit study of any given approach is limited.18,23,36,44-46 There remains a clear need to improve the uptake of existing reporting standards to ensure the future evidence base will be of high quality.44 In the meantime, a large portion of the impetus for expanding the use of SDM remains based on principles of effective communication and championing a patient-centered philosophy of care.

Cultivating an effective approach

An oft-cited objection to the use of SDM in day-to-day clinical care is that it “takes too much time.”47 Like all excellent communication skills, SDM is best incorporated into a clinician’s approach to patient care. With practice, we have found this can be accomplished during routine patient encounters—eg, when providing general counsel, giving advice, providing education, answering questions. Given the interdependent relationship between evidence-based medicine and SDM, particularly in preference-sensitive conditions, SDM skills can facilitate efficient decision-making and patient satisfaction.48 To that end, clinician training on SDM techniques, especially those that emphasize the 3 core elements, can be particularly beneficial. These broadly applicable skills can be leveraged in an “SDM mindset,” even outside traditional preference-sensitive care situations, to enhance clinician–patient rapport, relationship, and satisfaction.

The future of SDM

More than 2 decades after SDM was introduced to clinical care, there remains much to do to improve uptake in primary care settings. An important strategy to increase the successful uptake of SDM for the typical clinician and patient is to emphasize the approach to framing the topic and discussion rather than to overemphasize decision aids.23 Continuing the trend of well-designed and accessible tools for clinical decision support at the point of care for clinicians, in addition to the sustained evolution of decision aids for patients, should help minimize the need for extensive background knowledge on a topic, increase accessibility, and enable an effective partnership with patients in their health care decisions.46 Ongoing, well-structured study and the use of common proposed standards in developing these tools and studying SDM implementation will provide long-term quality assurance.44

SDM has a role to play in health equity

SDM has a clear role to play in addressing health inequities. Values vary from person to person, and individuals exist along a variety of cultural, community, and other spectra that strongly influence their perception of what is most important to them. Moreover, clinicians’ assumptions typically do not correspond to a patient’s actual desire to engage in SDM nor to their overall likelihood of choosing any given treatment option.46 While many clinicians believe patients do not participate in SDM because they simply do not wish to, a systematic review and thematic synthesis by Joseph-Williams et al46 suggested a great number of patients are instead unable to take part in SDM due to barriers such as a lack of time availability, challenges in the structure of the health care system itself, and factors specific to the clinician–patient interaction such as patients feeling as though they don’t have “permission” to participate in SDM.

SDM may improve health equity, adherence, and outcomes in certain groups. For example, SDM has been suggested as a potential means to address disparities in outcomes for populations disproportionately affected by hypertension.24 The increased implementation of SDM practices, coupled with a genuine partnership between patients and care teams, may improve patient–clinician communication, enhance understanding of patient concerns and goals, and perhaps ultimately increase patient engagement and adherence.

Continue to: Being the change

Being the change

Effective framing of medical decisions in the context of best medical evidence and eliciting patient values supports continued evolution in health care delivery. The traditional, physician-directed patriarchal “one-size-fits-all” approach has evolved. Through the continued development and implementation of SDM techniques, the clinician’s approach to care will continue to advance.

Ultimately, patients and clinicians both benefit from the use of SDM—the patient benefits from explicit framing of the medical facts most relevant to their decision, and the physician benefits from enhanced knowledge of the patient’s values and considerations. When done well, SDM increases the likelihood that patients will receive the best care possible, concordant with their values and preferences and within the context of their unique circumstances, leading to improved knowledge, adherence, outcomes, and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew Mackwood, MD, One Medical Center Drive, Lebanon, NH 03756; [email protected]

1. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Mission and history—patient decision aids. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/mission.html

2. Healthwise. Informed Medical Decision Foundation. Accessed October 20, 2022. www.healthwise.org/specialpages/imdf.aspx

3. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5

4. Joosten EAG, DeFuentes-Merillas L, De Weert G, et al. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:219-226. doi: 10.1159/000126073

5. Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, et al. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:324-332. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.023

6. Goodwin JS, Nishi S, Zhou J, et al. Use of the shared decision-making visit for lung cancer screening among Medicare enrollees. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:716-718. doi: 10.1001/jamain ternmed.2018.6405

7. Brenner AT, Malo TL, Margolis M, et al. Evaluating shared decision-making for lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1311-1316. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3054

8. Nishi SPE, Lowenstein LM, Mendoza TR, et al. Shared decision-making for lung cancer screening: how well are we “sharing”? Chest. 2021;160:330-340. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.041

9. Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Health care quality, geographic variations, and the challenge of supply-sensitive care. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46:69-79. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.000

10. Hoefel L, O’Connor AM, Lewis KB, et al. 20th Anniversary update of the Ottawa decision support framework part 1: a systematic review of the decisional needs of people making health or social decisions. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:555-581. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20936209

11. Sheridan SL, Harris RP, Woolf SH. Shared decision-making about screening and chemoprevention: a suggested approach from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:56-66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.011

12. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision-making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361-1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6

13. Fowler FJ Jr, Barry MJ, Sepucha KR, et al. Let’s require patients to review a high-quality decision aid before receiving important tests and treatments. Med Care. 2021;59:1-5. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001440

14. Hargraves IG, Fournier AK, Montori VM, et al. Generalized shared decision-making approaches and patient problems. Adapting AHRQ’s SHARE approach for purposeful SDM. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:2192-2199. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.022

15. Price D. Sharing clinical decisions by discussing evidence with patients. Perm J. 2005;9:70-73. doi: 10.7812/TPP/05-006

16. Schrager S, Phillips G, Burnside E. Shared decision-making in cancer screening. Fam Pract Manag. 2017;24:5-10.

17. Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JCJM. Shared decision-making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1172-1179. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022

18. Hargraves I, LeBlanc A, Shah ND, et al. Shared decision-making: the need for patient-clinician conversation, not just information. Health Aff (Milford). 2016;35:627-629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1354

19. Stacey D, Légaré F, Boland L, et al. 20th anniversary Ottawa Decision Support Framework: part 3 overview of systematic reviews and updated framework. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:379-398. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20911870

20. Agency for Health Research and Quality. The SHARE Approach. Accessed November 24, 2021, www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/index.html

21. Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision-making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;359:j4891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4891

22. Healthwise – Informed Medical Decisions Foundation. The six steps of shared decision making. Accessed December 21, 2022. http://cdn-www.informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdfdocs/SixStepsSDM_CARD.pdf

23. Bomhof-Roordink H, Gärtner FR, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Key components of shared decision-making models: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031763. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-03176

24. Langford AT, Williams SK, Applegate M, et al. Partnerships to improve shared decision making for patients with hypertension - health equity implications. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(suppl 1):97-102. doi: 10.18865/ed.29.S1.97

25. MGH Health Decision Sciences Center. High cholesterol visit version 2. YouTube. February 28, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=o2mZ9duJW0A

26. MGH Health Decision Sciences Center. High cholesterol visit version 1. YouTube. February 28, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=0NdDMKS8DwU

27. MGH Health Decision Sciences Center. Videos about shared decision-making. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://mghdecision sciences.org/tools-training/sdmvideos/

28. Elwyn G, Dehlendorf C, Epstein RM, et al. Shared decision-making and motivational interviewing: achieving patient-centered care across the spectrum of health care problems. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:270-275. doi: 10.1370/afm.1615. Published correction in Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:301. doi: 10.1370/afm.1674

29. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Rollnick S. Dual equipoise shared decision-making: definitions for decision and behaviour support interventions. Implement Sci. 2009;4:75. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-75

30. Agency for Health Research and Quality. The SHARE approach—communicating numbers to your patients: a reference guide for health care providers. Workshop curriculum: tool 5. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/tool/resource-5.html

31. EBSCO. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://optiongrid.ebsco.com/about

32. HealthDecision. HealthDecision - Decision Support & Shared decision-making for Clinicians & Patients at the Point of Care. Accessed November 24, 2021. www.healthdecision.com/ [Now DynaMed Decisions, https://decisions.dynamed.com/]

33. Wolters Kluwer. EmmiEngage: guide patients in their care journeys. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/emmi/emmi-engage

34. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Patient decision aids. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/Azinvent.php

35. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Alphabetical list of decision aids by health topic. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZlist.html

36. Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision-making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114-131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638

37. Durand M-A, Carpenter L, Dolan H, et al. Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2014;9:e94670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094670

38. Friedberg MW, Van Busum K, Wexler R, et al. A demonstration of shared decision-making in primary care highlights barriers to adoption and potential remedies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:268-275. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1084

39. Braddock C 3rd, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, et al. “Surgery is certainly one good option”: quality and time-efficiency of informed decision-making in surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1830-1838. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00840

40. Arterburn D, Wellman R, Westbrook E, et al. Introducing decision aids at Group Health was linked to sharply lower hip and knee surgery rates and costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:2094-2104. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0686.

41. Vina ER, Richardson D, Medvedeva E, et al. Does a patient-centered educational intervention affect African-American access to knee replacement? A randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1755-1764. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4834-z

42. Ibrahim SA, Blum M, Lee GC, et al. Effect of a decision aid on access to total knee replacement for Black patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e164225. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4225

43. Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, et al. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:9-18. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004

44. Trenaman L, Jansen J, Blumenthal-Barby J, et al. Are we improving? Update and critical appraisal of the reporting of decision process and quality measures in trials evaluating patient decision aids. Med Decis Making. 2021;41:954-959. doi: 10.1177/0272989x211011120

45. Hoefel L, Lewis KB, O’Connor A, et al. 20th anniversary update of the Ottawa decision support framework: part 2 subanalysis of a systematic review of patient decision aids. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:522-539. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20924645

46. Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:291-309. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031

47. Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:526-535. doi: 10.1016/ j.pec.2008.07.018

48. Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Del Mar C. The connection between evidence-based medicine and shared decision-making. JAMA. 2014;312:1295-1296. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10186

Shared decision-making (SDM), a methodology for improving patient communication, education, and outcomes in preference-sensitive health care decisions, debuted in 1989 with the Ottawa Decision Support Framework1 and the creation of the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (now the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation).2 SDM enhances care by actively involving patients as partners in their health care choices. This approach can not only increase patient knowledge and satisfaction with care but also has a beneficial effect on adherence and outcomes.3-5

Despite the significant benefits of SDM, overall uptake of SDM practices remains low—even in situations in which SDM is a requirement for reimbursement, such as in lung cancer screening.6-8 The ever-shifting list of conditions that warrant the implementation of SDM in a family practice can be daunting. Our review seeks to highlight current best practices, review common situations in which SDM would be beneficial, and describe tools and frameworks that can facilitate effective SDM conversations in the typical primary care practice.

Preference-sensitive care

SDM is designed to enhance the role of patient preference, considering a patient’s own personal values for managing clinical conditions when more than one reasonable strategy exists. Such situations are often referred to as preference-sensitive conditions—ie, since evidence is limited on a single “best” treatment approach, patients’ values should impact decision-making.9 Examples of common preference-sensitive situations that include preventive care, screening, and chronic disease management are outlined in TABLE 1.

How to engage patients

In preference-sensitive care situations, SDM endeavors to address uncertainty by laying out what the options are, as well as providing risk and benefit data. This helps inform patients and guides providers about individual patient preference on whether to screen (eg, for average-risk female patients, breast cancer screening between ages 40-50 years). SDM can assist with determining whether to screen and if so, at what interval (eg, at 1- or 2-year intervals), while acknowledging that no single decision would be “best” for every patient.

While there are formalized tools to provide information to patients and help them consider their values and choices,3,10 SDM does not hinge on the use of an explicit tool.11-18 There are many approaches to and interpretations of SDM; the Ottawa Decision Support Framework reviews and details these many considerations at length in its 2020 revision.19 TABLE 211,15-17,20-22 highlights various SDM frameworks and the steps involved.

These 3 elements are commonamong SDM frameworks

In a 2019 systematic review, the following 3 elements were highlighted as the most prevalent over time across SDM frameworks and could be considered core to any meaningful SDM process23:

Explicit effort by 2 or more experts. The patient is an expert in their own values. The clinician, as an expert in relevant medical knowledge, clarifies that the current medical situation will benefit from incorporating the patient’s preferences to arrive at an appropriate shared decision.

Continue to: Effort to provide relevant...

Effort to provide relevant, evidence-based information. The clinician provides treatment options applicable to the patient, including the risks and benefits of each (potentially using one of the decision aids in the following section), to facilitate a values-based discussion and decision.

Patient support and assistance. The clinician assists the patient in navigating next steps based on the treatment decision and arranges necessary follow-up.

Various case studies and examples of SDM conversations have been published.15-17,24 Video examples of optimal25 and less than optimal26 SDM conversations are available on the Massachusetts General Hospital Health Decision Sciences Center website (https://mghdecisionsciences.org/) under the section “Tools & Training >> Videos about Shared Decision-Making.”27

SDM and motivational interviewing: Both can serve you well

SDM and motivational interviewing share many common elements,28 and it’s useful to take advantage of both techniques. Preference-sensitive care situations may require a combination of approaches.

For example, motivational interviewing may be a beneficial tool when dealing with a patient who is initially against colon cancer screening (evidence clearly favors screening in some form over no screening) and has a history of avoiding medical care. Through an SDM approach, motivational interviewing may identify an opportunity to prioritize the patient’s preference to minimize medical intervention by ensuring that the patient is familiar with noninvasive colon cancer screening options. After sufficiently eliciting a patient value aligned with screening and engaging the patient’s own motivations for follow-through, a more thorough SDM conversation can then help clarify the best options.

Continue to: A proposed framework...

A proposed framework for identifying whether SDM or motivational interviewing is appropriate is featured in the FIGURE. In their paper, Elwyn et al29 further define and discuss the distinguishing features and roles of SDM and behavioral support interventions, such as motivational interviewing.

Tools to facilitate SDM conversations

Decision aids

SDM has historically been operationalized for study through the use of decision aids: formally structured materials describing, in detail, the available treatment options under consideration, including the relative risks and benefits. Frequently, such tools are framed from a patient perspective, with digestible information presented in a multimedia format (eg, visual risk representations of “1 out of 10” in an icon array vs “10%”), leveraging effective risk communication strategies (eg, absolute risk rates vs relative risks and “balanced framing”). For instance, the physician would note that 1 out of 10 patients have an outcome and 9 out of 10 do not.

Additional information on risk communication skills is available at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s webpage on the SHARE approach (www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/tool/resource-5.html).30 Decision aids have been shown to enhance health literacy, increase patient knowledge and understanding, and promote the frequency of “values-concordant” choices.3

Point-of-care decision support

A more recent trend in SDM is increased development and use of point-of-care decision support tools that emphasize information reflecting individual patient circumstances (eg, leveraging heart risk calculators to individualize risk conversations when considering statins for primary prevention of heart disease based on lipids and other demographic factors). An advantage to using such tools is that they provide “just-in-time” detailed and personalized evidence-based information, guiding the discussion and minimizing the need for an extensive advance review of each topic by emphasizing the “key facts.” To ensure effective use of SDM tools, avoid oversaturating patients with data, maintain a focus on patient values, and engage in a 2-way discussion that considers the unique mix of preferences and circumstances.

Proprietorship of tools and decision aids

Until recently, SDM materials were compiled primarily within not-for-profit entities such as the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, which became a division of Healthwise in 2014.2 In recent years, there has been an increasing trend of for-profit companies acquiring or developing their own decision aids and decision-support tools, eg, EBSCO Health (Option Grid31 and Health Decision32) and Wolters Kluwer (EMMI33). The extensive work of curating SDM and educational tools to keep up with best medical evidence is costly, and the effort to defray costs can give rise to potential conflicts of interest. Therefore, the interests of the creators of such tools—whether commercial or academic—should always be considered when evaluating the use of a given decision-support tool.

Contunue to: An online listing...

An online listing of publicly available decision aids is maintained by the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute,34 which reviews decision-aid quality by objective criteria in addition to providing direct links to resources.35 EBSCO health’s DynaMed Decisions also maintains a list of shared decision-making tools (https://decisions.dynamed.com/).

Effectiveness of decision aids

There is a robust body of research focused on decision aids for SDM. An example is a 2017 Cochrane review that concluded SDM facilitated by decision aids significantly improved patient engagement and satisfaction and increased patient knowledge, accuracy in risk perception, and congruency in making value-aligned care choices. Beyond decision aids, studies show SDM practices increase patient knowledge, engagement, and satisfaction, particularly among low-literacy or disadvantaged groups.4,36,37

Barriers to implementation

Clinicians frequently cite time constraints as a barrier to successfully implementing SDM in practice, although studies that explicitly compare the time/cost of SDM to “usual care” are limited.38 A Cochrane review of 105 studies evaluating the use of decision aids vs usual care found that only 10 studies examined the effects of decision aids on the length of the office visit.3 Two of these studies (one evaluating decision aids for prenatal diagnostic screening and the other for atrial fibrillation) found a median increase in visit length of 2.6 minutes (24 vs 21; 7.5% increase); the other 8 studies reported no increase in visit length.3

Studies focusing on the time impact of using SDM in an office visit, rather than decision aids as a proxy for SDM, are few. A study by Braddock et al39 assessed the elements of SDM, measuring the quality and the time-efficiency of 141 surgical decision-making interactions between patients and 89 orthopedic surgeons. Researchers found 57% of the discussions had elements of SDM sufficient to meet a “reasonable minimum” standard (eg, nature of the decision, patient’s role, patient’s preference). These conversations took 20 minutes compared to a median of 16 minutes for a more typical conversation.39 The study used audiotaped interviews, which were coded and scored based on the presence of SDM elements; treatment choice, outcomes of the choices, and satisfaction were not reported. A separate study by Loh et al5 looking at SDM in primary care for patients with depression sought to determine whether patient participation in the decision-making process improved treatment adherence, outcomes, and patient satisfaction without increasing consultation time. This study, which included 23 physicians and 405 patients, found improved participation and satisfaction outcomes in the intervention group and no difference in consultation time between the intervention and control groups.5

Care costs appear similar

The impact of SDM on cost and patient-centered clinical outcomes is not well defined. One study by Arterburn et al40 found decision aids and SDM lowered the rates of elective surgery for hip and knee arthritis, as well as associated health system costs. However, other studies suggest this phenomenon likely varies by demographic, demonstrating that certain populations with a generally lower baseline preference for surgery on average chose surgery more often after SDM interventions.41,42 Evidence does support patient acceptability and efficacy for SDM in longitudinal care when the approach is incorporated into decisions over multiple visits or long-term decisions for chronic conditions.4 Studies comparing patient groups receiving decision aids to usual care have shown similar or lower overall care costs for the decision-aid group.3

Continue to: Limitations to the evidence

Limitations to the evidence

Systematic reviews routinely note substantial heterogeneity in the literature on SDM use, owing to variable definitions of what steps are essential to constitute an SDM intervention and a wide variety of outcome measures used, as well as the broad range of conditions to which SDM is potentially applicable.3,4,10,36,37,43-45 While efforts in SDM education, uptake, and study frequently adapt frameworks such as those outlined in TABLE 2,11,15-17,20-22 there is as yet no one consensus on the “best” approach to SDM, and explicit study of any given approach is limited.18,23,36,44-46 There remains a clear need to improve the uptake of existing reporting standards to ensure the future evidence base will be of high quality.44 In the meantime, a large portion of the impetus for expanding the use of SDM remains based on principles of effective communication and championing a patient-centered philosophy of care.

Cultivating an effective approach

An oft-cited objection to the use of SDM in day-to-day clinical care is that it “takes too much time.”47 Like all excellent communication skills, SDM is best incorporated into a clinician’s approach to patient care. With practice, we have found this can be accomplished during routine patient encounters—eg, when providing general counsel, giving advice, providing education, answering questions. Given the interdependent relationship between evidence-based medicine and SDM, particularly in preference-sensitive conditions, SDM skills can facilitate efficient decision-making and patient satisfaction.48 To that end, clinician training on SDM techniques, especially those that emphasize the 3 core elements, can be particularly beneficial. These broadly applicable skills can be leveraged in an “SDM mindset,” even outside traditional preference-sensitive care situations, to enhance clinician–patient rapport, relationship, and satisfaction.

The future of SDM

More than 2 decades after SDM was introduced to clinical care, there remains much to do to improve uptake in primary care settings. An important strategy to increase the successful uptake of SDM for the typical clinician and patient is to emphasize the approach to framing the topic and discussion rather than to overemphasize decision aids.23 Continuing the trend of well-designed and accessible tools for clinical decision support at the point of care for clinicians, in addition to the sustained evolution of decision aids for patients, should help minimize the need for extensive background knowledge on a topic, increase accessibility, and enable an effective partnership with patients in their health care decisions.46 Ongoing, well-structured study and the use of common proposed standards in developing these tools and studying SDM implementation will provide long-term quality assurance.44

SDM has a role to play in health equity

SDM has a clear role to play in addressing health inequities. Values vary from person to person, and individuals exist along a variety of cultural, community, and other spectra that strongly influence their perception of what is most important to them. Moreover, clinicians’ assumptions typically do not correspond to a patient’s actual desire to engage in SDM nor to their overall likelihood of choosing any given treatment option.46 While many clinicians believe patients do not participate in SDM because they simply do not wish to, a systematic review and thematic synthesis by Joseph-Williams et al46 suggested a great number of patients are instead unable to take part in SDM due to barriers such as a lack of time availability, challenges in the structure of the health care system itself, and factors specific to the clinician–patient interaction such as patients feeling as though they don’t have “permission” to participate in SDM.

SDM may improve health equity, adherence, and outcomes in certain groups. For example, SDM has been suggested as a potential means to address disparities in outcomes for populations disproportionately affected by hypertension.24 The increased implementation of SDM practices, coupled with a genuine partnership between patients and care teams, may improve patient–clinician communication, enhance understanding of patient concerns and goals, and perhaps ultimately increase patient engagement and adherence.

Continue to: Being the change

Being the change

Effective framing of medical decisions in the context of best medical evidence and eliciting patient values supports continued evolution in health care delivery. The traditional, physician-directed patriarchal “one-size-fits-all” approach has evolved. Through the continued development and implementation of SDM techniques, the clinician’s approach to care will continue to advance.

Ultimately, patients and clinicians both benefit from the use of SDM—the patient benefits from explicit framing of the medical facts most relevant to their decision, and the physician benefits from enhanced knowledge of the patient’s values and considerations. When done well, SDM increases the likelihood that patients will receive the best care possible, concordant with their values and preferences and within the context of their unique circumstances, leading to improved knowledge, adherence, outcomes, and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew Mackwood, MD, One Medical Center Drive, Lebanon, NH 03756; [email protected]

Shared decision-making (SDM), a methodology for improving patient communication, education, and outcomes in preference-sensitive health care decisions, debuted in 1989 with the Ottawa Decision Support Framework1 and the creation of the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (now the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation).2 SDM enhances care by actively involving patients as partners in their health care choices. This approach can not only increase patient knowledge and satisfaction with care but also has a beneficial effect on adherence and outcomes.3-5

Despite the significant benefits of SDM, overall uptake of SDM practices remains low—even in situations in which SDM is a requirement for reimbursement, such as in lung cancer screening.6-8 The ever-shifting list of conditions that warrant the implementation of SDM in a family practice can be daunting. Our review seeks to highlight current best practices, review common situations in which SDM would be beneficial, and describe tools and frameworks that can facilitate effective SDM conversations in the typical primary care practice.

Preference-sensitive care

SDM is designed to enhance the role of patient preference, considering a patient’s own personal values for managing clinical conditions when more than one reasonable strategy exists. Such situations are often referred to as preference-sensitive conditions—ie, since evidence is limited on a single “best” treatment approach, patients’ values should impact decision-making.9 Examples of common preference-sensitive situations that include preventive care, screening, and chronic disease management are outlined in TABLE 1.

How to engage patients

In preference-sensitive care situations, SDM endeavors to address uncertainty by laying out what the options are, as well as providing risk and benefit data. This helps inform patients and guides providers about individual patient preference on whether to screen (eg, for average-risk female patients, breast cancer screening between ages 40-50 years). SDM can assist with determining whether to screen and if so, at what interval (eg, at 1- or 2-year intervals), while acknowledging that no single decision would be “best” for every patient.

While there are formalized tools to provide information to patients and help them consider their values and choices,3,10 SDM does not hinge on the use of an explicit tool.11-18 There are many approaches to and interpretations of SDM; the Ottawa Decision Support Framework reviews and details these many considerations at length in its 2020 revision.19 TABLE 211,15-17,20-22 highlights various SDM frameworks and the steps involved.

These 3 elements are commonamong SDM frameworks

In a 2019 systematic review, the following 3 elements were highlighted as the most prevalent over time across SDM frameworks and could be considered core to any meaningful SDM process23:

Explicit effort by 2 or more experts. The patient is an expert in their own values. The clinician, as an expert in relevant medical knowledge, clarifies that the current medical situation will benefit from incorporating the patient’s preferences to arrive at an appropriate shared decision.

Continue to: Effort to provide relevant...

Effort to provide relevant, evidence-based information. The clinician provides treatment options applicable to the patient, including the risks and benefits of each (potentially using one of the decision aids in the following section), to facilitate a values-based discussion and decision.

Patient support and assistance. The clinician assists the patient in navigating next steps based on the treatment decision and arranges necessary follow-up.

Various case studies and examples of SDM conversations have been published.15-17,24 Video examples of optimal25 and less than optimal26 SDM conversations are available on the Massachusetts General Hospital Health Decision Sciences Center website (https://mghdecisionsciences.org/) under the section “Tools & Training >> Videos about Shared Decision-Making.”27

SDM and motivational interviewing: Both can serve you well

SDM and motivational interviewing share many common elements,28 and it’s useful to take advantage of both techniques. Preference-sensitive care situations may require a combination of approaches.

For example, motivational interviewing may be a beneficial tool when dealing with a patient who is initially against colon cancer screening (evidence clearly favors screening in some form over no screening) and has a history of avoiding medical care. Through an SDM approach, motivational interviewing may identify an opportunity to prioritize the patient’s preference to minimize medical intervention by ensuring that the patient is familiar with noninvasive colon cancer screening options. After sufficiently eliciting a patient value aligned with screening and engaging the patient’s own motivations for follow-through, a more thorough SDM conversation can then help clarify the best options.

Continue to: A proposed framework...

A proposed framework for identifying whether SDM or motivational interviewing is appropriate is featured in the FIGURE. In their paper, Elwyn et al29 further define and discuss the distinguishing features and roles of SDM and behavioral support interventions, such as motivational interviewing.

Tools to facilitate SDM conversations

Decision aids

SDM has historically been operationalized for study through the use of decision aids: formally structured materials describing, in detail, the available treatment options under consideration, including the relative risks and benefits. Frequently, such tools are framed from a patient perspective, with digestible information presented in a multimedia format (eg, visual risk representations of “1 out of 10” in an icon array vs “10%”), leveraging effective risk communication strategies (eg, absolute risk rates vs relative risks and “balanced framing”). For instance, the physician would note that 1 out of 10 patients have an outcome and 9 out of 10 do not.

Additional information on risk communication skills is available at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s webpage on the SHARE approach (www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/tool/resource-5.html).30 Decision aids have been shown to enhance health literacy, increase patient knowledge and understanding, and promote the frequency of “values-concordant” choices.3

Point-of-care decision support

A more recent trend in SDM is increased development and use of point-of-care decision support tools that emphasize information reflecting individual patient circumstances (eg, leveraging heart risk calculators to individualize risk conversations when considering statins for primary prevention of heart disease based on lipids and other demographic factors). An advantage to using such tools is that they provide “just-in-time” detailed and personalized evidence-based information, guiding the discussion and minimizing the need for an extensive advance review of each topic by emphasizing the “key facts.” To ensure effective use of SDM tools, avoid oversaturating patients with data, maintain a focus on patient values, and engage in a 2-way discussion that considers the unique mix of preferences and circumstances.

Proprietorship of tools and decision aids

Until recently, SDM materials were compiled primarily within not-for-profit entities such as the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, which became a division of Healthwise in 2014.2 In recent years, there has been an increasing trend of for-profit companies acquiring or developing their own decision aids and decision-support tools, eg, EBSCO Health (Option Grid31 and Health Decision32) and Wolters Kluwer (EMMI33). The extensive work of curating SDM and educational tools to keep up with best medical evidence is costly, and the effort to defray costs can give rise to potential conflicts of interest. Therefore, the interests of the creators of such tools—whether commercial or academic—should always be considered when evaluating the use of a given decision-support tool.

Contunue to: An online listing...

An online listing of publicly available decision aids is maintained by the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute,34 which reviews decision-aid quality by objective criteria in addition to providing direct links to resources.35 EBSCO health’s DynaMed Decisions also maintains a list of shared decision-making tools (https://decisions.dynamed.com/).

Effectiveness of decision aids

There is a robust body of research focused on decision aids for SDM. An example is a 2017 Cochrane review that concluded SDM facilitated by decision aids significantly improved patient engagement and satisfaction and increased patient knowledge, accuracy in risk perception, and congruency in making value-aligned care choices. Beyond decision aids, studies show SDM practices increase patient knowledge, engagement, and satisfaction, particularly among low-literacy or disadvantaged groups.4,36,37

Barriers to implementation

Clinicians frequently cite time constraints as a barrier to successfully implementing SDM in practice, although studies that explicitly compare the time/cost of SDM to “usual care” are limited.38 A Cochrane review of 105 studies evaluating the use of decision aids vs usual care found that only 10 studies examined the effects of decision aids on the length of the office visit.3 Two of these studies (one evaluating decision aids for prenatal diagnostic screening and the other for atrial fibrillation) found a median increase in visit length of 2.6 minutes (24 vs 21; 7.5% increase); the other 8 studies reported no increase in visit length.3

Studies focusing on the time impact of using SDM in an office visit, rather than decision aids as a proxy for SDM, are few. A study by Braddock et al39 assessed the elements of SDM, measuring the quality and the time-efficiency of 141 surgical decision-making interactions between patients and 89 orthopedic surgeons. Researchers found 57% of the discussions had elements of SDM sufficient to meet a “reasonable minimum” standard (eg, nature of the decision, patient’s role, patient’s preference). These conversations took 20 minutes compared to a median of 16 minutes for a more typical conversation.39 The study used audiotaped interviews, which were coded and scored based on the presence of SDM elements; treatment choice, outcomes of the choices, and satisfaction were not reported. A separate study by Loh et al5 looking at SDM in primary care for patients with depression sought to determine whether patient participation in the decision-making process improved treatment adherence, outcomes, and patient satisfaction without increasing consultation time. This study, which included 23 physicians and 405 patients, found improved participation and satisfaction outcomes in the intervention group and no difference in consultation time between the intervention and control groups.5

Care costs appear similar

The impact of SDM on cost and patient-centered clinical outcomes is not well defined. One study by Arterburn et al40 found decision aids and SDM lowered the rates of elective surgery for hip and knee arthritis, as well as associated health system costs. However, other studies suggest this phenomenon likely varies by demographic, demonstrating that certain populations with a generally lower baseline preference for surgery on average chose surgery more often after SDM interventions.41,42 Evidence does support patient acceptability and efficacy for SDM in longitudinal care when the approach is incorporated into decisions over multiple visits or long-term decisions for chronic conditions.4 Studies comparing patient groups receiving decision aids to usual care have shown similar or lower overall care costs for the decision-aid group.3

Continue to: Limitations to the evidence

Limitations to the evidence

Systematic reviews routinely note substantial heterogeneity in the literature on SDM use, owing to variable definitions of what steps are essential to constitute an SDM intervention and a wide variety of outcome measures used, as well as the broad range of conditions to which SDM is potentially applicable.3,4,10,36,37,43-45 While efforts in SDM education, uptake, and study frequently adapt frameworks such as those outlined in TABLE 2,11,15-17,20-22 there is as yet no one consensus on the “best” approach to SDM, and explicit study of any given approach is limited.18,23,36,44-46 There remains a clear need to improve the uptake of existing reporting standards to ensure the future evidence base will be of high quality.44 In the meantime, a large portion of the impetus for expanding the use of SDM remains based on principles of effective communication and championing a patient-centered philosophy of care.

Cultivating an effective approach

An oft-cited objection to the use of SDM in day-to-day clinical care is that it “takes too much time.”47 Like all excellent communication skills, SDM is best incorporated into a clinician’s approach to patient care. With practice, we have found this can be accomplished during routine patient encounters—eg, when providing general counsel, giving advice, providing education, answering questions. Given the interdependent relationship between evidence-based medicine and SDM, particularly in preference-sensitive conditions, SDM skills can facilitate efficient decision-making and patient satisfaction.48 To that end, clinician training on SDM techniques, especially those that emphasize the 3 core elements, can be particularly beneficial. These broadly applicable skills can be leveraged in an “SDM mindset,” even outside traditional preference-sensitive care situations, to enhance clinician–patient rapport, relationship, and satisfaction.

The future of SDM

More than 2 decades after SDM was introduced to clinical care, there remains much to do to improve uptake in primary care settings. An important strategy to increase the successful uptake of SDM for the typical clinician and patient is to emphasize the approach to framing the topic and discussion rather than to overemphasize decision aids.23 Continuing the trend of well-designed and accessible tools for clinical decision support at the point of care for clinicians, in addition to the sustained evolution of decision aids for patients, should help minimize the need for extensive background knowledge on a topic, increase accessibility, and enable an effective partnership with patients in their health care decisions.46 Ongoing, well-structured study and the use of common proposed standards in developing these tools and studying SDM implementation will provide long-term quality assurance.44

SDM has a role to play in health equity

SDM has a clear role to play in addressing health inequities. Values vary from person to person, and individuals exist along a variety of cultural, community, and other spectra that strongly influence their perception of what is most important to them. Moreover, clinicians’ assumptions typically do not correspond to a patient’s actual desire to engage in SDM nor to their overall likelihood of choosing any given treatment option.46 While many clinicians believe patients do not participate in SDM because they simply do not wish to, a systematic review and thematic synthesis by Joseph-Williams et al46 suggested a great number of patients are instead unable to take part in SDM due to barriers such as a lack of time availability, challenges in the structure of the health care system itself, and factors specific to the clinician–patient interaction such as patients feeling as though they don’t have “permission” to participate in SDM.

SDM may improve health equity, adherence, and outcomes in certain groups. For example, SDM has been suggested as a potential means to address disparities in outcomes for populations disproportionately affected by hypertension.24 The increased implementation of SDM practices, coupled with a genuine partnership between patients and care teams, may improve patient–clinician communication, enhance understanding of patient concerns and goals, and perhaps ultimately increase patient engagement and adherence.

Continue to: Being the change

Being the change

Effective framing of medical decisions in the context of best medical evidence and eliciting patient values supports continued evolution in health care delivery. The traditional, physician-directed patriarchal “one-size-fits-all” approach has evolved. Through the continued development and implementation of SDM techniques, the clinician’s approach to care will continue to advance.

Ultimately, patients and clinicians both benefit from the use of SDM—the patient benefits from explicit framing of the medical facts most relevant to their decision, and the physician benefits from enhanced knowledge of the patient’s values and considerations. When done well, SDM increases the likelihood that patients will receive the best care possible, concordant with their values and preferences and within the context of their unique circumstances, leading to improved knowledge, adherence, outcomes, and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew Mackwood, MD, One Medical Center Drive, Lebanon, NH 03756; [email protected]

1. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Mission and history—patient decision aids. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/mission.html

2. Healthwise. Informed Medical Decision Foundation. Accessed October 20, 2022. www.healthwise.org/specialpages/imdf.aspx

3. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5

4. Joosten EAG, DeFuentes-Merillas L, De Weert G, et al. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:219-226. doi: 10.1159/000126073

5. Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, et al. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:324-332. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.023

6. Goodwin JS, Nishi S, Zhou J, et al. Use of the shared decision-making visit for lung cancer screening among Medicare enrollees. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:716-718. doi: 10.1001/jamain ternmed.2018.6405

7. Brenner AT, Malo TL, Margolis M, et al. Evaluating shared decision-making for lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1311-1316. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3054

8. Nishi SPE, Lowenstein LM, Mendoza TR, et al. Shared decision-making for lung cancer screening: how well are we “sharing”? Chest. 2021;160:330-340. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.041

9. Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Health care quality, geographic variations, and the challenge of supply-sensitive care. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46:69-79. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.000

10. Hoefel L, O’Connor AM, Lewis KB, et al. 20th Anniversary update of the Ottawa decision support framework part 1: a systematic review of the decisional needs of people making health or social decisions. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:555-581. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20936209

11. Sheridan SL, Harris RP, Woolf SH. Shared decision-making about screening and chemoprevention: a suggested approach from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:56-66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.011

12. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision-making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361-1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6

13. Fowler FJ Jr, Barry MJ, Sepucha KR, et al. Let’s require patients to review a high-quality decision aid before receiving important tests and treatments. Med Care. 2021;59:1-5. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001440

14. Hargraves IG, Fournier AK, Montori VM, et al. Generalized shared decision-making approaches and patient problems. Adapting AHRQ’s SHARE approach for purposeful SDM. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:2192-2199. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.022

15. Price D. Sharing clinical decisions by discussing evidence with patients. Perm J. 2005;9:70-73. doi: 10.7812/TPP/05-006

16. Schrager S, Phillips G, Burnside E. Shared decision-making in cancer screening. Fam Pract Manag. 2017;24:5-10.

17. Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JCJM. Shared decision-making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1172-1179. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022

18. Hargraves I, LeBlanc A, Shah ND, et al. Shared decision-making: the need for patient-clinician conversation, not just information. Health Aff (Milford). 2016;35:627-629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1354

19. Stacey D, Légaré F, Boland L, et al. 20th anniversary Ottawa Decision Support Framework: part 3 overview of systematic reviews and updated framework. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:379-398. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20911870

20. Agency for Health Research and Quality. The SHARE Approach. Accessed November 24, 2021, www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/index.html

21. Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision-making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;359:j4891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4891

22. Healthwise – Informed Medical Decisions Foundation. The six steps of shared decision making. Accessed December 21, 2022. http://cdn-www.informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdfdocs/SixStepsSDM_CARD.pdf

23. Bomhof-Roordink H, Gärtner FR, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Key components of shared decision-making models: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031763. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-03176

24. Langford AT, Williams SK, Applegate M, et al. Partnerships to improve shared decision making for patients with hypertension - health equity implications. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(suppl 1):97-102. doi: 10.18865/ed.29.S1.97

25. MGH Health Decision Sciences Center. High cholesterol visit version 2. YouTube. February 28, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=o2mZ9duJW0A

26. MGH Health Decision Sciences Center. High cholesterol visit version 1. YouTube. February 28, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=0NdDMKS8DwU

27. MGH Health Decision Sciences Center. Videos about shared decision-making. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://mghdecision sciences.org/tools-training/sdmvideos/

28. Elwyn G, Dehlendorf C, Epstein RM, et al. Shared decision-making and motivational interviewing: achieving patient-centered care across the spectrum of health care problems. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:270-275. doi: 10.1370/afm.1615. Published correction in Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:301. doi: 10.1370/afm.1674

29. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Rollnick S. Dual equipoise shared decision-making: definitions for decision and behaviour support interventions. Implement Sci. 2009;4:75. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-75

30. Agency for Health Research and Quality. The SHARE approach—communicating numbers to your patients: a reference guide for health care providers. Workshop curriculum: tool 5. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/tool/resource-5.html

31. EBSCO. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://optiongrid.ebsco.com/about

32. HealthDecision. HealthDecision - Decision Support & Shared decision-making for Clinicians & Patients at the Point of Care. Accessed November 24, 2021. www.healthdecision.com/ [Now DynaMed Decisions, https://decisions.dynamed.com/]

33. Wolters Kluwer. EmmiEngage: guide patients in their care journeys. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/emmi/emmi-engage

34. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Patient decision aids. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/Azinvent.php

35. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Alphabetical list of decision aids by health topic. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZlist.html

36. Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision-making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114-131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638

37. Durand M-A, Carpenter L, Dolan H, et al. Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2014;9:e94670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094670

38. Friedberg MW, Van Busum K, Wexler R, et al. A demonstration of shared decision-making in primary care highlights barriers to adoption and potential remedies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:268-275. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1084

39. Braddock C 3rd, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, et al. “Surgery is certainly one good option”: quality and time-efficiency of informed decision-making in surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1830-1838. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00840

40. Arterburn D, Wellman R, Westbrook E, et al. Introducing decision aids at Group Health was linked to sharply lower hip and knee surgery rates and costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:2094-2104. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0686.

41. Vina ER, Richardson D, Medvedeva E, et al. Does a patient-centered educational intervention affect African-American access to knee replacement? A randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1755-1764. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4834-z

42. Ibrahim SA, Blum M, Lee GC, et al. Effect of a decision aid on access to total knee replacement for Black patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e164225. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4225

43. Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, et al. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:9-18. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004

44. Trenaman L, Jansen J, Blumenthal-Barby J, et al. Are we improving? Update and critical appraisal of the reporting of decision process and quality measures in trials evaluating patient decision aids. Med Decis Making. 2021;41:954-959. doi: 10.1177/0272989x211011120

45. Hoefel L, Lewis KB, O’Connor A, et al. 20th anniversary update of the Ottawa decision support framework: part 2 subanalysis of a systematic review of patient decision aids. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:522-539. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20924645

46. Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:291-309. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031

47. Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:526-535. doi: 10.1016/ j.pec.2008.07.018

48. Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Del Mar C. The connection between evidence-based medicine and shared decision-making. JAMA. 2014;312:1295-1296. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10186

1. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Mission and history—patient decision aids. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/mission.html

2. Healthwise. Informed Medical Decision Foundation. Accessed October 20, 2022. www.healthwise.org/specialpages/imdf.aspx

3. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5

4. Joosten EAG, DeFuentes-Merillas L, De Weert G, et al. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:219-226. doi: 10.1159/000126073

5. Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, et al. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:324-332. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.023

6. Goodwin JS, Nishi S, Zhou J, et al. Use of the shared decision-making visit for lung cancer screening among Medicare enrollees. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:716-718. doi: 10.1001/jamain ternmed.2018.6405

7. Brenner AT, Malo TL, Margolis M, et al. Evaluating shared decision-making for lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1311-1316. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3054

8. Nishi SPE, Lowenstein LM, Mendoza TR, et al. Shared decision-making for lung cancer screening: how well are we “sharing”? Chest. 2021;160:330-340. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.041

9. Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Health care quality, geographic variations, and the challenge of supply-sensitive care. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46:69-79. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.000

10. Hoefel L, O’Connor AM, Lewis KB, et al. 20th Anniversary update of the Ottawa decision support framework part 1: a systematic review of the decisional needs of people making health or social decisions. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:555-581. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20936209

11. Sheridan SL, Harris RP, Woolf SH. Shared decision-making about screening and chemoprevention: a suggested approach from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:56-66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.011

12. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision-making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361-1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6

13. Fowler FJ Jr, Barry MJ, Sepucha KR, et al. Let’s require patients to review a high-quality decision aid before receiving important tests and treatments. Med Care. 2021;59:1-5. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001440

14. Hargraves IG, Fournier AK, Montori VM, et al. Generalized shared decision-making approaches and patient problems. Adapting AHRQ’s SHARE approach for purposeful SDM. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:2192-2199. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.022

15. Price D. Sharing clinical decisions by discussing evidence with patients. Perm J. 2005;9:70-73. doi: 10.7812/TPP/05-006

16. Schrager S, Phillips G, Burnside E. Shared decision-making in cancer screening. Fam Pract Manag. 2017;24:5-10.

17. Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JCJM. Shared decision-making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1172-1179. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022

18. Hargraves I, LeBlanc A, Shah ND, et al. Shared decision-making: the need for patient-clinician conversation, not just information. Health Aff (Milford). 2016;35:627-629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1354

19. Stacey D, Légaré F, Boland L, et al. 20th anniversary Ottawa Decision Support Framework: part 3 overview of systematic reviews and updated framework. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:379-398. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20911870

20. Agency for Health Research and Quality. The SHARE Approach. Accessed November 24, 2021, www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/index.html

21. Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision-making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;359:j4891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4891

22. Healthwise – Informed Medical Decisions Foundation. The six steps of shared decision making. Accessed December 21, 2022. http://cdn-www.informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdfdocs/SixStepsSDM_CARD.pdf

23. Bomhof-Roordink H, Gärtner FR, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Key components of shared decision-making models: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031763. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-03176

24. Langford AT, Williams SK, Applegate M, et al. Partnerships to improve shared decision making for patients with hypertension - health equity implications. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(suppl 1):97-102. doi: 10.18865/ed.29.S1.97

25. MGH Health Decision Sciences Center. High cholesterol visit version 2. YouTube. February 28, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=o2mZ9duJW0A

26. MGH Health Decision Sciences Center. High cholesterol visit version 1. YouTube. February 28, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=0NdDMKS8DwU

27. MGH Health Decision Sciences Center. Videos about shared decision-making. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://mghdecision sciences.org/tools-training/sdmvideos/

28. Elwyn G, Dehlendorf C, Epstein RM, et al. Shared decision-making and motivational interviewing: achieving patient-centered care across the spectrum of health care problems. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:270-275. doi: 10.1370/afm.1615. Published correction in Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:301. doi: 10.1370/afm.1674

29. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Rollnick S. Dual equipoise shared decision-making: definitions for decision and behaviour support interventions. Implement Sci. 2009;4:75. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-75

30. Agency for Health Research and Quality. The SHARE approach—communicating numbers to your patients: a reference guide for health care providers. Workshop curriculum: tool 5. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/tool/resource-5.html

31. EBSCO. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://optiongrid.ebsco.com/about

32. HealthDecision. HealthDecision - Decision Support & Shared decision-making for Clinicians & Patients at the Point of Care. Accessed November 24, 2021. www.healthdecision.com/ [Now DynaMed Decisions, https://decisions.dynamed.com/]

33. Wolters Kluwer. EmmiEngage: guide patients in their care journeys. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/emmi/emmi-engage

34. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Patient decision aids. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/Azinvent.php

35. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Alphabetical list of decision aids by health topic. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZlist.html

36. Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision-making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114-131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638

37. Durand M-A, Carpenter L, Dolan H, et al. Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2014;9:e94670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094670

38. Friedberg MW, Van Busum K, Wexler R, et al. A demonstration of shared decision-making in primary care highlights barriers to adoption and potential remedies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:268-275. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1084