User login

Today’s hospitals must address a variety of challenges stemming from the expectation to provide more services and better quality with fewer financial, material, and human resources. According to the annual survey conducted by the American Hospital Association (AHA) in 2003, total expenses for all U.S. community hospitals were more than $450 billion. In managing these expenditures, hospitals face the following pressures:

- Cost increases in medical supplies and pharmaceuticals.

- Record shortages of nurses, pharmacists, and technicians.

- A growing uncompensated patient pool.

- Annual potential reductions in Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

- Rising bad debt resulting from greater patient responsibility for the cost of care.

- The diversion of more profitable cases to specialty and freestanding ambulatory care facilities and surgery centers.

- Soaring costs associated with adequately serving high-risk conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS.

- Discounted reimbursement rates with insurers.

- Increasing pressure to commit financial resources to clinical information technology.

- The need to fund infrastructure improvements and physical plant renovations as well as expansions to address increasing demand (1).

To overcome these challenges, hospitals must find innovative ways to balance revenues and expenses, fund necessary capital investments, and satisfy the public’s demand for quality, safety, and accessibility.

Hospitalist Programs: A Good Investment

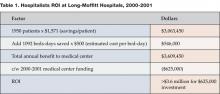

One solution to the above-mentioned situations is a hospitalist program, which, in its short history, has already had a profound impact on inpatient care. Robert M. Wachter, MD, associate chair in the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and medical service chief at Moffitt-Long Hospitals, coined the term Hospitalist in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1996 (2). At the 2002 annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), Wachter presented findings from a study conducted at his institution. The results demonstrate a significant return on investment (ROI) of 5.8:1 when a hospitalist program is utilized (See Table 1 for details) (3).

How do hospitalists reduce length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay? William David Rifkin, MD, associate director of the Yale Primary Care Residency Program, offers three basic reasons why hospitalist programs contribute to effective and efficient use of resources. Since hospitalists are physically onsite, they are better able to react to condition changes and requests for consultations in a timely manner, he asserts. Also, being familiar with the hospital’s systems of care, the hospitalist knows who to call and how to utilize the services of social workers and other contingency staff when arranging for post-discharge care. Third, Rifkin indicates that inpatients today are sicker than they were in past years, a fact well known and understood by hospitalists. “There is an increased level of acuity,” he says. “Hospitalists are used to seeing these kinds of patients. They are more comfortable taking care of these patients and will see more of them with any given diagnosis” (4).

In one of his studies, Rifkin noted a reduction in LOS for inpatients with a pneumonia diagnosis. “The hospitalist had switched the patient from IV (intravenous) to oral antibiotics,” he says. Reacting quickly to indications that the patient was ready for a change in treatment modality facilitated an earlier discharge (5).

L. Craig Miller, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Baptist Health Care, reports that his hospital saved $2.56 million in 2 years as a direct result of its inpatient management program (6). Although attention to technical and clinical details is important, Miller emphasizes the critical role the human factor plays, specifically the impact of teamwork, on achieving resource utilization savings.

“Hospitalists work as a team, collaborating with physicians and ED doctors,” he says. This cooperative spirit enables the efficient use of manpower in patient care. Miller adds that at Baptist, as is the case at most hospitals, the medical complexity of patients dictates a need for cooperation in order to successfully treat illness. The presence of hospitalists facilitates the team effort, causing a positive trickle down effect regarding LOS, readmission and mortality rates, he affirms. “The hospitalist provides focused leadership to utilization resource management,” says Miller (7).

In the role of inpatient leader, the hospitalist also facilitates ED throughput, which results in another area of cost savings for the hospital. Paola Coppola, MD, ED director at Brookhaven Memorial Hospital Medical Center, says, “From an ER perspective, a call to the hospitalist replaces multiple calls to specialists. In general, hospitalists feel much more comfortable treating a wide array of conditions including infectious disease, pneumonias, strokes, and chest pain without the intervention of specialists in that field. Hence, hospital consumption of resources decreases, which in turn lowers length of stay.” He echoes Rifkin’s thoughts on quick response time. “Hospitalists provide an immediately available service, thus saving ER physicians valuable time. This ensures faster turnover, better throughput, makes more ER beds available, and services more patients, eventually helping the hospital’s bottom line,” says Coppola (8).

In addition to teamwork, 24/7 availability is vital to the wise utilization of resources, according to Anthony Shallash, MD, vice president of medical affairs at Brookhaven. “The fact of 24/7 presence allows rapid responses to patient condition and problems. Continuous and close monitoring of patients allows them to be upgraded or downgraded as needed,” he says. “As such, LOS is decreased and quite favorable as compared to peer practitioners for similar disease severity. Resources consumed and tests ordered also show a favorable trend” (9).

A recently published study (10) by researchers at Dartmouth Medical School documents the variation in the volume and cost of services that academic medical centers use in treating patients. Hospitals were categorized as low- and high-intensity, with significant differences in cost per case. For example, the high-intensity hospitals spent up to 47% more on care for acute myocardial infarction. In an interview in Today’s Hospitalist (11), the lead author, Elliott S. Fisher, MD, professor of medicine and community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, described the importance of coordination in achieving efficient care. Fisher says, “I think there’s a real opportunity for hospitalists to improve the care of patients in both high- and low- intensity hospitals. Having ten doctors involved in a given patient’s care may not be a good thing, unless someone [i.e., the hospitalist] is doing a really good job of coordinating that care.”

Hospitalists focus only on inpatient medicine. They are familiar with managing the most common medical diagnoses, such as community acquired pneumonia, diabetes. and congestive heart failure. Hospitalist programs often develop uniform and consistent ways of treating these patients. Cogent Healthcare, a national hospitalist management company has implemented the “Cogent Care Guides,” best practice guidelines for high-volume hospital diagnoses. Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP and Cogent’s chief medical officer, says “The Cogent Care Guides ensure best practices are implemented at critical points in the patient’s care… decreasing the variability of care that results in inefficiencies.” Greeno added, “The care guidelines [also] support the timely notification of the primary care physician of nine critical landmark events related to patient status that can affect outcomes” (12).

Stacy Goldsholl, Director of the Covenant HealthCare Hospital Medicine Program in Saginaw, MI, suggests other ways that hospitalists can generate utilization savings for their hospitals. “Hospitalists often eliminate unnecessary admissions and shift work-ups to the ambulatory setting. For example, I recently arranged an outpatient colonoscopy for a pneumonia patient with a stable hemoglobin and heme positive stool. Because of my experience treating patients with pneumonia, I was able to determine that the circumstances did not require an inpatient stay.” In addition, Dr. Goldsholl has found that the hospitalists in her program are quite effective in classifying “observation” patients, eliminating reimbursement conflicts with Medicare, Medicaid, and other insurers.

Finally, because they are always in the hospital rather than sharing time between the office and hospital, hospitalists can improve inpatient continuity of care, resulting in lower costs and better outcomes. Adrienne Bennett, MD, chief of the hospital medicine service at Newton-Wellesley Hospital near Boston, examined cases managed by hospitalists and non-hospitalist community physicians, comparing the number of “handoffs” of responsibility that occur among attending physicians. Community physicians share inpatient responsibility in their practices and sometimes their partners round on their patients. Every time another physician assumes responsibility for a patient, there is the potential for a loss of information and a discontinuity of care. At Newton-Wellesley Hospital, the hospitalists work a schedule of 14 days on, followed by 7 days off. “We found that hospitalists averaged less than half the number of handoffs as the community physicians,” says Bennett. “This may be one of the reasons that hospitalists have better case mix adjusted utilization performance.”

Stakeholder Analysis

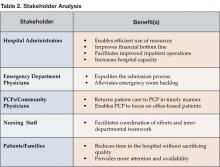

Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated that hospitalists provide value to a wide range of stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. With regard to resource utilization savings, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the listed stakeholders (Table 2).

Published Research Results

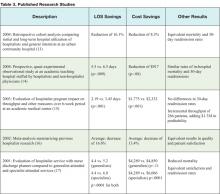

Dozens of studies demonstrate the positive effects hospitalist programs have on resource utilization. Observational, retrospective, and prospective data analyses have been conducted at community-based hospitals as well as at academic medical institutions. Findings consistently indicate that hospitalist programs result in resource savings for patients, physicians. and hospital medicine. A range of studies shown in Table 3 represent the most recent efforts at tracking hospitalist programs and their effects on resource utilization.

Conclusion

According to the AHA’s 2003 survey of healthcare trends, the fiscal health of the nation’s hospitals will most likely remain fragile and variable in the coming years. The survey cites declining operating margins, a continued decrease in reimbursement, labor shortages, and rising insurance and pharmaceutical costs, as well as the need to invest in technology and facility maintenance and upkeep as key factors. However, hospitalists have proven time and again in clinical studies that they can bring value to the operation of a healthcare facility. With reduced lengths of stay, decreased overall hospital costs, and equivalent — if not superior — quality, hospitalists can contribute significantly to a hospital’s healthy bottom line.

Dr. Syed can be contacted at [email protected].

References

- ACP Research Center, Environmental Assessment: Trends in hospital financing. 2003. www.aha.org.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7

- Wachter RM. Presentation, Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual meeting 2002. 4. Rifkin WD. Telephone interview December 15, 2004.

- Rifkin WD, Conner D, Silver A, Eichom A. Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community-based primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:1053-8.

- “Hospitalists save $2.5 million and decrease LOS.” Healthcare Benchmarks and Quality Improvement, May 2004.

- Miller LC. Telephone intewiew, November 16, 2004.

- Coppola P. Email interview, December 15,2004.

- Shallash A. Email interview, December17, 2004.

- Healthaffairs.org, “Use of Medicare claims data to monitor provider-specific performance among patients with severe chronic illness.” 10.1377/hlthaff.var.5. Posting date: October 7, 2004.

- Why less really can be more when it comes to teaching hospitals. Today’s Hospitalist. 2004 December.

- Greeno R. Chief medical officer, Cogent Healthcare, Irvine, California. Telephone interview. December 16, 2004.

- Everett GD, Anton MP Jackson BK, Swigert C, Uddin N. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay associated with general internists and hospitalist physicians at a community hospital. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:626-30.

- Kaboli PJ, Barnett MJ, Rosenthal GE. Associations with reduced length of stay and costs on an academic hospitalist service. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:561-8.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Services Research. 2003:38(3):905-18; discussion 919-22.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287:487-94.

- Palmer HC, Armistead NS, Elnicki DM, et al. The effect of a hospitalist service with nurse discharge planner on patient care in an academic teaching hospital. Am J Med. 2001;111:627-32.

Today’s hospitals must address a variety of challenges stemming from the expectation to provide more services and better quality with fewer financial, material, and human resources. According to the annual survey conducted by the American Hospital Association (AHA) in 2003, total expenses for all U.S. community hospitals were more than $450 billion. In managing these expenditures, hospitals face the following pressures:

- Cost increases in medical supplies and pharmaceuticals.

- Record shortages of nurses, pharmacists, and technicians.

- A growing uncompensated patient pool.

- Annual potential reductions in Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

- Rising bad debt resulting from greater patient responsibility for the cost of care.

- The diversion of more profitable cases to specialty and freestanding ambulatory care facilities and surgery centers.

- Soaring costs associated with adequately serving high-risk conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS.

- Discounted reimbursement rates with insurers.

- Increasing pressure to commit financial resources to clinical information technology.

- The need to fund infrastructure improvements and physical plant renovations as well as expansions to address increasing demand (1).

To overcome these challenges, hospitals must find innovative ways to balance revenues and expenses, fund necessary capital investments, and satisfy the public’s demand for quality, safety, and accessibility.

Hospitalist Programs: A Good Investment

One solution to the above-mentioned situations is a hospitalist program, which, in its short history, has already had a profound impact on inpatient care. Robert M. Wachter, MD, associate chair in the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and medical service chief at Moffitt-Long Hospitals, coined the term Hospitalist in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1996 (2). At the 2002 annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), Wachter presented findings from a study conducted at his institution. The results demonstrate a significant return on investment (ROI) of 5.8:1 when a hospitalist program is utilized (See Table 1 for details) (3).

How do hospitalists reduce length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay? William David Rifkin, MD, associate director of the Yale Primary Care Residency Program, offers three basic reasons why hospitalist programs contribute to effective and efficient use of resources. Since hospitalists are physically onsite, they are better able to react to condition changes and requests for consultations in a timely manner, he asserts. Also, being familiar with the hospital’s systems of care, the hospitalist knows who to call and how to utilize the services of social workers and other contingency staff when arranging for post-discharge care. Third, Rifkin indicates that inpatients today are sicker than they were in past years, a fact well known and understood by hospitalists. “There is an increased level of acuity,” he says. “Hospitalists are used to seeing these kinds of patients. They are more comfortable taking care of these patients and will see more of them with any given diagnosis” (4).

In one of his studies, Rifkin noted a reduction in LOS for inpatients with a pneumonia diagnosis. “The hospitalist had switched the patient from IV (intravenous) to oral antibiotics,” he says. Reacting quickly to indications that the patient was ready for a change in treatment modality facilitated an earlier discharge (5).

L. Craig Miller, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Baptist Health Care, reports that his hospital saved $2.56 million in 2 years as a direct result of its inpatient management program (6). Although attention to technical and clinical details is important, Miller emphasizes the critical role the human factor plays, specifically the impact of teamwork, on achieving resource utilization savings.

“Hospitalists work as a team, collaborating with physicians and ED doctors,” he says. This cooperative spirit enables the efficient use of manpower in patient care. Miller adds that at Baptist, as is the case at most hospitals, the medical complexity of patients dictates a need for cooperation in order to successfully treat illness. The presence of hospitalists facilitates the team effort, causing a positive trickle down effect regarding LOS, readmission and mortality rates, he affirms. “The hospitalist provides focused leadership to utilization resource management,” says Miller (7).

In the role of inpatient leader, the hospitalist also facilitates ED throughput, which results in another area of cost savings for the hospital. Paola Coppola, MD, ED director at Brookhaven Memorial Hospital Medical Center, says, “From an ER perspective, a call to the hospitalist replaces multiple calls to specialists. In general, hospitalists feel much more comfortable treating a wide array of conditions including infectious disease, pneumonias, strokes, and chest pain without the intervention of specialists in that field. Hence, hospital consumption of resources decreases, which in turn lowers length of stay.” He echoes Rifkin’s thoughts on quick response time. “Hospitalists provide an immediately available service, thus saving ER physicians valuable time. This ensures faster turnover, better throughput, makes more ER beds available, and services more patients, eventually helping the hospital’s bottom line,” says Coppola (8).

In addition to teamwork, 24/7 availability is vital to the wise utilization of resources, according to Anthony Shallash, MD, vice president of medical affairs at Brookhaven. “The fact of 24/7 presence allows rapid responses to patient condition and problems. Continuous and close monitoring of patients allows them to be upgraded or downgraded as needed,” he says. “As such, LOS is decreased and quite favorable as compared to peer practitioners for similar disease severity. Resources consumed and tests ordered also show a favorable trend” (9).

A recently published study (10) by researchers at Dartmouth Medical School documents the variation in the volume and cost of services that academic medical centers use in treating patients. Hospitals were categorized as low- and high-intensity, with significant differences in cost per case. For example, the high-intensity hospitals spent up to 47% more on care for acute myocardial infarction. In an interview in Today’s Hospitalist (11), the lead author, Elliott S. Fisher, MD, professor of medicine and community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, described the importance of coordination in achieving efficient care. Fisher says, “I think there’s a real opportunity for hospitalists to improve the care of patients in both high- and low- intensity hospitals. Having ten doctors involved in a given patient’s care may not be a good thing, unless someone [i.e., the hospitalist] is doing a really good job of coordinating that care.”

Hospitalists focus only on inpatient medicine. They are familiar with managing the most common medical diagnoses, such as community acquired pneumonia, diabetes. and congestive heart failure. Hospitalist programs often develop uniform and consistent ways of treating these patients. Cogent Healthcare, a national hospitalist management company has implemented the “Cogent Care Guides,” best practice guidelines for high-volume hospital diagnoses. Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP and Cogent’s chief medical officer, says “The Cogent Care Guides ensure best practices are implemented at critical points in the patient’s care… decreasing the variability of care that results in inefficiencies.” Greeno added, “The care guidelines [also] support the timely notification of the primary care physician of nine critical landmark events related to patient status that can affect outcomes” (12).

Stacy Goldsholl, Director of the Covenant HealthCare Hospital Medicine Program in Saginaw, MI, suggests other ways that hospitalists can generate utilization savings for their hospitals. “Hospitalists often eliminate unnecessary admissions and shift work-ups to the ambulatory setting. For example, I recently arranged an outpatient colonoscopy for a pneumonia patient with a stable hemoglobin and heme positive stool. Because of my experience treating patients with pneumonia, I was able to determine that the circumstances did not require an inpatient stay.” In addition, Dr. Goldsholl has found that the hospitalists in her program are quite effective in classifying “observation” patients, eliminating reimbursement conflicts with Medicare, Medicaid, and other insurers.

Finally, because they are always in the hospital rather than sharing time between the office and hospital, hospitalists can improve inpatient continuity of care, resulting in lower costs and better outcomes. Adrienne Bennett, MD, chief of the hospital medicine service at Newton-Wellesley Hospital near Boston, examined cases managed by hospitalists and non-hospitalist community physicians, comparing the number of “handoffs” of responsibility that occur among attending physicians. Community physicians share inpatient responsibility in their practices and sometimes their partners round on their patients. Every time another physician assumes responsibility for a patient, there is the potential for a loss of information and a discontinuity of care. At Newton-Wellesley Hospital, the hospitalists work a schedule of 14 days on, followed by 7 days off. “We found that hospitalists averaged less than half the number of handoffs as the community physicians,” says Bennett. “This may be one of the reasons that hospitalists have better case mix adjusted utilization performance.”

Stakeholder Analysis

Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated that hospitalists provide value to a wide range of stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. With regard to resource utilization savings, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the listed stakeholders (Table 2).

Published Research Results

Dozens of studies demonstrate the positive effects hospitalist programs have on resource utilization. Observational, retrospective, and prospective data analyses have been conducted at community-based hospitals as well as at academic medical institutions. Findings consistently indicate that hospitalist programs result in resource savings for patients, physicians. and hospital medicine. A range of studies shown in Table 3 represent the most recent efforts at tracking hospitalist programs and their effects on resource utilization.

Conclusion

According to the AHA’s 2003 survey of healthcare trends, the fiscal health of the nation’s hospitals will most likely remain fragile and variable in the coming years. The survey cites declining operating margins, a continued decrease in reimbursement, labor shortages, and rising insurance and pharmaceutical costs, as well as the need to invest in technology and facility maintenance and upkeep as key factors. However, hospitalists have proven time and again in clinical studies that they can bring value to the operation of a healthcare facility. With reduced lengths of stay, decreased overall hospital costs, and equivalent — if not superior — quality, hospitalists can contribute significantly to a hospital’s healthy bottom line.

Dr. Syed can be contacted at [email protected].

References

- ACP Research Center, Environmental Assessment: Trends in hospital financing. 2003. www.aha.org.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7

- Wachter RM. Presentation, Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual meeting 2002. 4. Rifkin WD. Telephone interview December 15, 2004.

- Rifkin WD, Conner D, Silver A, Eichom A. Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community-based primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:1053-8.

- “Hospitalists save $2.5 million and decrease LOS.” Healthcare Benchmarks and Quality Improvement, May 2004.

- Miller LC. Telephone intewiew, November 16, 2004.

- Coppola P. Email interview, December 15,2004.

- Shallash A. Email interview, December17, 2004.

- Healthaffairs.org, “Use of Medicare claims data to monitor provider-specific performance among patients with severe chronic illness.” 10.1377/hlthaff.var.5. Posting date: October 7, 2004.

- Why less really can be more when it comes to teaching hospitals. Today’s Hospitalist. 2004 December.

- Greeno R. Chief medical officer, Cogent Healthcare, Irvine, California. Telephone interview. December 16, 2004.

- Everett GD, Anton MP Jackson BK, Swigert C, Uddin N. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay associated with general internists and hospitalist physicians at a community hospital. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:626-30.

- Kaboli PJ, Barnett MJ, Rosenthal GE. Associations with reduced length of stay and costs on an academic hospitalist service. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:561-8.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Services Research. 2003:38(3):905-18; discussion 919-22.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287:487-94.

- Palmer HC, Armistead NS, Elnicki DM, et al. The effect of a hospitalist service with nurse discharge planner on patient care in an academic teaching hospital. Am J Med. 2001;111:627-32.

Today’s hospitals must address a variety of challenges stemming from the expectation to provide more services and better quality with fewer financial, material, and human resources. According to the annual survey conducted by the American Hospital Association (AHA) in 2003, total expenses for all U.S. community hospitals were more than $450 billion. In managing these expenditures, hospitals face the following pressures:

- Cost increases in medical supplies and pharmaceuticals.

- Record shortages of nurses, pharmacists, and technicians.

- A growing uncompensated patient pool.

- Annual potential reductions in Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

- Rising bad debt resulting from greater patient responsibility for the cost of care.

- The diversion of more profitable cases to specialty and freestanding ambulatory care facilities and surgery centers.

- Soaring costs associated with adequately serving high-risk conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS.

- Discounted reimbursement rates with insurers.

- Increasing pressure to commit financial resources to clinical information technology.

- The need to fund infrastructure improvements and physical plant renovations as well as expansions to address increasing demand (1).

To overcome these challenges, hospitals must find innovative ways to balance revenues and expenses, fund necessary capital investments, and satisfy the public’s demand for quality, safety, and accessibility.

Hospitalist Programs: A Good Investment

One solution to the above-mentioned situations is a hospitalist program, which, in its short history, has already had a profound impact on inpatient care. Robert M. Wachter, MD, associate chair in the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and medical service chief at Moffitt-Long Hospitals, coined the term Hospitalist in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1996 (2). At the 2002 annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), Wachter presented findings from a study conducted at his institution. The results demonstrate a significant return on investment (ROI) of 5.8:1 when a hospitalist program is utilized (See Table 1 for details) (3).

How do hospitalists reduce length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay? William David Rifkin, MD, associate director of the Yale Primary Care Residency Program, offers three basic reasons why hospitalist programs contribute to effective and efficient use of resources. Since hospitalists are physically onsite, they are better able to react to condition changes and requests for consultations in a timely manner, he asserts. Also, being familiar with the hospital’s systems of care, the hospitalist knows who to call and how to utilize the services of social workers and other contingency staff when arranging for post-discharge care. Third, Rifkin indicates that inpatients today are sicker than they were in past years, a fact well known and understood by hospitalists. “There is an increased level of acuity,” he says. “Hospitalists are used to seeing these kinds of patients. They are more comfortable taking care of these patients and will see more of them with any given diagnosis” (4).

In one of his studies, Rifkin noted a reduction in LOS for inpatients with a pneumonia diagnosis. “The hospitalist had switched the patient from IV (intravenous) to oral antibiotics,” he says. Reacting quickly to indications that the patient was ready for a change in treatment modality facilitated an earlier discharge (5).

L. Craig Miller, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Baptist Health Care, reports that his hospital saved $2.56 million in 2 years as a direct result of its inpatient management program (6). Although attention to technical and clinical details is important, Miller emphasizes the critical role the human factor plays, specifically the impact of teamwork, on achieving resource utilization savings.

“Hospitalists work as a team, collaborating with physicians and ED doctors,” he says. This cooperative spirit enables the efficient use of manpower in patient care. Miller adds that at Baptist, as is the case at most hospitals, the medical complexity of patients dictates a need for cooperation in order to successfully treat illness. The presence of hospitalists facilitates the team effort, causing a positive trickle down effect regarding LOS, readmission and mortality rates, he affirms. “The hospitalist provides focused leadership to utilization resource management,” says Miller (7).

In the role of inpatient leader, the hospitalist also facilitates ED throughput, which results in another area of cost savings for the hospital. Paola Coppola, MD, ED director at Brookhaven Memorial Hospital Medical Center, says, “From an ER perspective, a call to the hospitalist replaces multiple calls to specialists. In general, hospitalists feel much more comfortable treating a wide array of conditions including infectious disease, pneumonias, strokes, and chest pain without the intervention of specialists in that field. Hence, hospital consumption of resources decreases, which in turn lowers length of stay.” He echoes Rifkin’s thoughts on quick response time. “Hospitalists provide an immediately available service, thus saving ER physicians valuable time. This ensures faster turnover, better throughput, makes more ER beds available, and services more patients, eventually helping the hospital’s bottom line,” says Coppola (8).

In addition to teamwork, 24/7 availability is vital to the wise utilization of resources, according to Anthony Shallash, MD, vice president of medical affairs at Brookhaven. “The fact of 24/7 presence allows rapid responses to patient condition and problems. Continuous and close monitoring of patients allows them to be upgraded or downgraded as needed,” he says. “As such, LOS is decreased and quite favorable as compared to peer practitioners for similar disease severity. Resources consumed and tests ordered also show a favorable trend” (9).

A recently published study (10) by researchers at Dartmouth Medical School documents the variation in the volume and cost of services that academic medical centers use in treating patients. Hospitals were categorized as low- and high-intensity, with significant differences in cost per case. For example, the high-intensity hospitals spent up to 47% more on care for acute myocardial infarction. In an interview in Today’s Hospitalist (11), the lead author, Elliott S. Fisher, MD, professor of medicine and community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, described the importance of coordination in achieving efficient care. Fisher says, “I think there’s a real opportunity for hospitalists to improve the care of patients in both high- and low- intensity hospitals. Having ten doctors involved in a given patient’s care may not be a good thing, unless someone [i.e., the hospitalist] is doing a really good job of coordinating that care.”

Hospitalists focus only on inpatient medicine. They are familiar with managing the most common medical diagnoses, such as community acquired pneumonia, diabetes. and congestive heart failure. Hospitalist programs often develop uniform and consistent ways of treating these patients. Cogent Healthcare, a national hospitalist management company has implemented the “Cogent Care Guides,” best practice guidelines for high-volume hospital diagnoses. Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP and Cogent’s chief medical officer, says “The Cogent Care Guides ensure best practices are implemented at critical points in the patient’s care… decreasing the variability of care that results in inefficiencies.” Greeno added, “The care guidelines [also] support the timely notification of the primary care physician of nine critical landmark events related to patient status that can affect outcomes” (12).

Stacy Goldsholl, Director of the Covenant HealthCare Hospital Medicine Program in Saginaw, MI, suggests other ways that hospitalists can generate utilization savings for their hospitals. “Hospitalists often eliminate unnecessary admissions and shift work-ups to the ambulatory setting. For example, I recently arranged an outpatient colonoscopy for a pneumonia patient with a stable hemoglobin and heme positive stool. Because of my experience treating patients with pneumonia, I was able to determine that the circumstances did not require an inpatient stay.” In addition, Dr. Goldsholl has found that the hospitalists in her program are quite effective in classifying “observation” patients, eliminating reimbursement conflicts with Medicare, Medicaid, and other insurers.

Finally, because they are always in the hospital rather than sharing time between the office and hospital, hospitalists can improve inpatient continuity of care, resulting in lower costs and better outcomes. Adrienne Bennett, MD, chief of the hospital medicine service at Newton-Wellesley Hospital near Boston, examined cases managed by hospitalists and non-hospitalist community physicians, comparing the number of “handoffs” of responsibility that occur among attending physicians. Community physicians share inpatient responsibility in their practices and sometimes their partners round on their patients. Every time another physician assumes responsibility for a patient, there is the potential for a loss of information and a discontinuity of care. At Newton-Wellesley Hospital, the hospitalists work a schedule of 14 days on, followed by 7 days off. “We found that hospitalists averaged less than half the number of handoffs as the community physicians,” says Bennett. “This may be one of the reasons that hospitalists have better case mix adjusted utilization performance.”

Stakeholder Analysis

Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated that hospitalists provide value to a wide range of stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. With regard to resource utilization savings, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the listed stakeholders (Table 2).

Published Research Results

Dozens of studies demonstrate the positive effects hospitalist programs have on resource utilization. Observational, retrospective, and prospective data analyses have been conducted at community-based hospitals as well as at academic medical institutions. Findings consistently indicate that hospitalist programs result in resource savings for patients, physicians. and hospital medicine. A range of studies shown in Table 3 represent the most recent efforts at tracking hospitalist programs and their effects on resource utilization.

Conclusion

According to the AHA’s 2003 survey of healthcare trends, the fiscal health of the nation’s hospitals will most likely remain fragile and variable in the coming years. The survey cites declining operating margins, a continued decrease in reimbursement, labor shortages, and rising insurance and pharmaceutical costs, as well as the need to invest in technology and facility maintenance and upkeep as key factors. However, hospitalists have proven time and again in clinical studies that they can bring value to the operation of a healthcare facility. With reduced lengths of stay, decreased overall hospital costs, and equivalent — if not superior — quality, hospitalists can contribute significantly to a hospital’s healthy bottom line.

Dr. Syed can be contacted at [email protected].

References

- ACP Research Center, Environmental Assessment: Trends in hospital financing. 2003. www.aha.org.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7

- Wachter RM. Presentation, Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual meeting 2002. 4. Rifkin WD. Telephone interview December 15, 2004.

- Rifkin WD, Conner D, Silver A, Eichom A. Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community-based primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:1053-8.

- “Hospitalists save $2.5 million and decrease LOS.” Healthcare Benchmarks and Quality Improvement, May 2004.

- Miller LC. Telephone intewiew, November 16, 2004.

- Coppola P. Email interview, December 15,2004.

- Shallash A. Email interview, December17, 2004.

- Healthaffairs.org, “Use of Medicare claims data to monitor provider-specific performance among patients with severe chronic illness.” 10.1377/hlthaff.var.5. Posting date: October 7, 2004.

- Why less really can be more when it comes to teaching hospitals. Today’s Hospitalist. 2004 December.

- Greeno R. Chief medical officer, Cogent Healthcare, Irvine, California. Telephone interview. December 16, 2004.

- Everett GD, Anton MP Jackson BK, Swigert C, Uddin N. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay associated with general internists and hospitalist physicians at a community hospital. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:626-30.

- Kaboli PJ, Barnett MJ, Rosenthal GE. Associations with reduced length of stay and costs on an academic hospitalist service. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:561-8.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Services Research. 2003:38(3):905-18; discussion 919-22.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287:487-94.

- Palmer HC, Armistead NS, Elnicki DM, et al. The effect of a hospitalist service with nurse discharge planner on patient care in an academic teaching hospital. Am J Med. 2001;111:627-32.