User login

While much of private health care in the U.S. is only beginning to confront the burgeoning opioid epidemic, the VA has a long-standing commitment to providing treatment to veterans struggling with substance use disorders. To understand the scope of the challenge and the VA’s approach, Federal Practitioner Editor-in-Chief Cynthia M.A. Geppert, MD, talked with Karen Drexler, MD, national mental health program director, substance use disorders. Dr. Drexler served in the U.S. Air Force for 8 years before joining the Atlanta VAMC in Georgia, where she directed the substance abuse treatment program. She is an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University. In 2014, Dr. Drexler was named deputy mental health program director, addictive disorders.

Editor-in-Chief Cynthia M.A. Geppert, MD. As national mental health program director for substance use disorders, what are the challenges facing VA substance use programs?

Karen Drexler, MD. The biggest challenge is the increasing demand for services. Veterans have been coming to the VA for mental health care in general and for substance use disorder treatment in particular. The most common substance use disorder that we treat in addition to tobacco is alcohol use disorder, and the demand for alcohol use disorder treatment continues to grow.

Also, with the opioid crisis, there’s increasing demand for opioid use disorder treatments, including what we recommend as first-line treatment, which is medication-assisted treatment using buprenorphine or methadone, or injectable naltrexone as a second-line treatment. Gearing up with medication-assisted treatment for both alcohol and opioid use disorders is probably our biggest challenge.

Dr. Geppert. What were the most important accomplishments of the VA substance abuse programs over the past 5 years?

Dr. Drexler. There have been a lot! First of all, one of the things I love about practicing within the VA is that we are an integrated health care system. When I talk with colleagues in the Emory system here in Atlanta and across the country, oftentimes mental health and substance use disorders are isolated. The funding streams through the public sector come in different ways. Third-party payers have carve-outs for behavioral health.

It’s really wonderful to be able to collaborate with my colleagues in primary care, medical specialty care, and general mental health care, to provide a holistic and team-based approach to our patients who have both medical and substance use disorder problems and often co-occurring mental illness. As we’ve moved from a hospital-based system to more outpatient [care], the VA continues to be able to collaborate through our electronic health records as well as just being able to pick up the phone or send a [Microsoft] Lync message or an Outlook encrypted e-mail to help facilitate that coordinated care.

Another accomplishment has been to [develop] policy. It’s one of our challenges, but it’s also an accomplishment even at this early stage. In 2008, we issued the Uniform Mental Health Services benefits package as part of VHA Handbook on Mental Health Services. From that very beginning, we have included medication-assisted therapy when indicated for veterans with substance use disorders.

Now, we also know there’s a lot of variability in the system, so not every facility is providing these indicated treatments yet; but at least it’s part of our policy, and it’s been a focus of ongoing quality improvement to make these treatments available for veterans when they need them.

Dr. Geppert. We’ve heard a lot lately about the CDC guidelines for prescribing opiates for chronic pain that were published earlier this year. How do you see these guidelines affecting the VA Opiate Safety Initiative? Do you see any important contradictions between current VA policy and these new guidelines?

Dr. Drexler. Yes—not necessarily with policy but with our VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines from 2010 and the new CDC guidelines. There’s a shift in emphasis. The 2010 VA/DoD guidelines were maybe a little too optimistic about the safety of opioids for chronic, noncancer pain. As time goes on, more evidence is mounting of the potential harms, including from my perspective, the risk of developing an opioid use disorder when taking opioid analgesics as prescribed.

In the 1990s and the early 2000s, experts in the field reassured us. They told us all—patients and providers alike—that if opioid analgesics were taken as prescribed for legitimate pain by people who didn’t have a previous history of a substance use disorder, they could take them and would not be at risk for becoming addicted. We now know that’s simply not true. Patients who take these medicines as prescribed by their providers end up developing tolerance, developing hyperalgesia, needing more and more medication to get the desired effect, and crossing that line from just physiologic tolerance to developing an opioid use disorder.

We now have better guidelines about where that risk increases. We have some data from observational studies that patients who are maintained on opioid analgesics that are < 50 mg of daily morphine equivalent dose (MED) tend not to have as high a risk of overdose as those who are maintained on more, but the risk of developing an opioid use disorder actually is not insignificant even below 50 mg MED.

The key for developing an opioid use disorder is how long the patient is on the treatment. For patients who take opioid analgesics for < 90 days—again, these are observational studies—very few went on to develop opioid use disorder. However, those who took it for > 90 days, even those who were maintained on < 36 mg MED, had a significantly increased risk of developing an opioid use disorder. And for those who were on the higher dose, say, > 120 mg MED, the risk went up to 122-fold.

We just don’t see those kinds of odds ratios elsewhere in medicine. You know, we address risk factors when it increases the risk by 50%, but this is 122-fold.

Dr. Geppert. Pain as the fifth vital sign had a dark side there. Is there anything else you want to say to us about the Opiate Safety Initiative?

Dr. Drexler. I think it’s been incredibly successful; but like any change, there are unintended consequences and challenges with any change, even a good change. One of the things that has been a good change is raising awareness that opioids are not the answer for chronic pain. We have better evidence that self-care strategies (movement, exercise, physical therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy for pain) help folks learn strategies for addressing automatic alarming thoughts about their pain—that it’s signaling something terrible when, really, it’s not. There are things that people can do to manage pain on their own. Those [strategies] are safer, and we have better evidence that they are effective than we have for opioids taken past 12 weeks.

Dr. Geppert. It’s really a paradigm shift in understanding. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 has proposed to allow some nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. What role does the VA see for PAs and NPs in patient care for veterans with substance use disorders with medication-assisted therapy, and do you think that’ll involve prescribing buprenorphine?

Dr. Drexler. One of the things that I love about practicing within the VA is working within an interdisciplinary team and having that team-based approach. When we work together, our results far outshine anything that any one of us could do separately. I am very much looking forward to being able to provide or collaborate with other federal partners like the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] to provide the training for VA NPs and PAs who are able to prescribe controlled substances with their state licensure to provide buprenorphine for our patients.

Even without that prescriptive authority, NPs and PAs are already important partners and members of the interdisciplinary team who are managing patients and providing the evidence-based counseling, the monitoring, following up urine drug screen results, and doing a lot of the management, but not signing the prescription that’s being provided now by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act-waivered physicians. But SAMHSA has yet to define what the 24 hours of training will be that NPs and PAs will need to complete in order to apply for their U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration waiver, but we’re very much looking forward to it. And I am in contact with colleagues at SAMHSA, and they promise me they will keep me informed when they have the regulations set out for us to follow.

Dr. Geppert. The new VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Substance Use Disorders were published earlier this year. Could you give us an overview of the guidelines and what’s significant for most of our providers in the field?

Dr. Drexler. I’m very excited about the guidelines. One of the first things you should know is that they are very evidence based. If you’ve been practicing medicine as long as I have, you’ll remember, when the first clinical practice guidelines came out, they were expert opinion. They got some of the leading practitioners and researchers in the country together, put them in a room, and said, “What do you think people should do to treat this disorder?” Over time, clinical practice guidelines have become more evidence based; and the VA/DoD collaborative follows a highly respected methodology called the GRADE methodology.

Let me explain that just briefly. It means that our recommendations are based on systematic reviews of the literature. We all have our own screens and filters and our favorite studies. And so, if you get a bunch of experts together, they may not have as dispassionate a view of the entire literature as when you do a systematic review; and that’s what we started with.

We followed a specific methodology as well that took into account not only the strength of the evidence where the gold standard is a randomized, controlled clinical trial and, even better than that, a meta-analysis of multiple clinical trials. And for our recommendations, the strength of the evidence was, by far, supported mostly by clinical trials or meta-analyses. So, when you look at the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines, and I hope you will, you can feel confident that what we’re recommending is not just pulled out of the sky or some idiosyncratic favorite thing that Karen Drexler likes. It’s really based on good, strong clinical evidence.

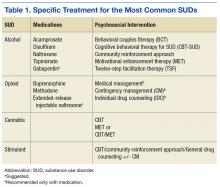

We went from the previous version that had over 160 recommendations. We distilled them down to 36, and those 36 recommendations cover everything from prevention in primary care settings to stabilization and withdrawal management for alcohol and sedatives and opioids, and then treatment or rehabilitation of the 4 most common substance use disorders and then some general principles (Table 1).

There’s good evidence that what we’re doing in VA with screening in primary care every year using the AUDIT-C [Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption] is making a difference (Table 2). That folks who screen positive for at-risk alcohol use are very likely to respond to a brief intervention by their health care provider and reduce their alcohol consumption to safe levels, where they’re not likely to go on to develop an addiction to the alcohol or to develop medical complications from heavy alcohol use.

After screening, then, if someone does develop a substance use disorder, we have evidence-based treatments, both medications for 2 of our most common disorders and psychosocial interventions for all 4 most common disorders after tobacco. And I don’t exclude tobacco because it’s not important; it’s incredibly important, but it gets its own clinical practice guidelines. So, with our limited budget, we just addressed the other 10 substances….

For alcohol we have great evidence for 5 different medications and for 6 different psychosocial approaches. It is the most common substance use disorder, but we also have a whole menu of different treatments that folks can choose from, everything from naltrexone—oral naltrexone is the most common medication that we prescribe—but also acamprosate; disulfiram; extended-release injectable naltrexone. Topiramate, interestingly, is not FDA approved for that indication, but we have found good evidence from clinical trials supporting topiramate, so we strongly recommend it. If any of those are not acceptable or not tolerated or ineffective, then we also have some evidence to support gabapentin as well. So we have a strong recommendation for the first ones and a suggestion for gabapentin if it’s clinically indicated.

In terms of psychosocial approaches, [we recommend] everything from motivation enhancement therapy or motivational interviewing; cognitive-behavioral therapy; 12-step facilitation, which is a structured way of getting folks to get more active in Alcoholics Anonymous; behavioral approaches like community reinforcement approach or contingency management.

For opioid use disorder, interestingly, we found good, strong evidence that medication-assisted treatments work but no evidence for any psychosocial intervention without medication. Let me say that again because, nationwide, the most common treatment that’s provided for opioid use disorder, for any substance use disorder, is a psychosocial intervention—talking therapy alone.

For all of the medicines for alcohol use disorder, the medicine improved upon talking therapy alone. For opioid use disorder, medication helps people stay sober; it retains them in treatment; it saves lives. But for talking therapy without medication, we have found insufficient evidence to recommend any particular treatment.

Dr. Geppert. Incredible. That leads to my next question: One of the most challenging issues facing primary care practitioners is how to manage patients who are on chronic opiate therapy but also use medical marijuana in the increasing number of states where it’s legal. Do you have some advice on how to approach these situations?

Dr. Drexler. It’s a great question, and it’s one I’m sure more and more VA practitioners are grappling with. By our policy, we do not exclude veterans who are taking medical marijuana from any VA services, and we encourage the veterans to speak up about it so that it can be considered as part of their treatment plan.

By policy, however, VA practitioners do not fill out forms for state-approved marijuana. Marijuana is still a Schedule I controlled substance by federal law, so it’s a very interesting legal situation where it’s illegal federally; but some states have passed laws making it legal by state law. It will be interesting to see how this plays out over the next few years.

But in that situation—and really, this is our policy, in general for substance use disorders—a patient having a substance use disorder should not be precluded or excluded from getting treatment for other medical conditions. Similarly, other medical conditions shouldn’t exclude patients from getting treatment for their substance use disorder. However, the best treatment comes when we look at the whole person and try to take both things into account.

In the same way that patients can become addicted to their opioid pain medicines, patients can become addicted to medical marijuana. So the marijuana use needs to be evaluated objectively; and whether or not they have a form, just like whether or not someone has a prescription for their opioid that may be causing them problems, that needs to be taken into account in the treatment plan; and the treatment needs to be individualized.

Dr. Geppert. What in VA substance use disorder programs and treatment do you think is especially innovative when compared to the community?

Dr. Drexler. One of the places where I think the VA is well ahead of our colleagues elsewhere in health care is…from SAIL [Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning] metrics. About 34% or 35% of veterans who are diagnosed clinically within our system with opioid use disorders are receiving medication-assisted therapy either with buprenorphine, methadone, or extended-release injectable naltrexone. When you look at the SAMHSA survey, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the percentage of patients in the community who meet criteria for a substance use disorder [who] actually receive treatment is more like 12%. We have no numbers from SAMHSA about what percentage are receiving medication-assisted treatment. They don’t ask. In that way, even though we have a long ways to go, we’re ahead of the curve when it comes to medication-assisted treatment. But the demand is growing, we’re going to have to keep working hard to keep up and to get ahead at this. When I think about it compared to other chronic illnesses, only 35% of our patients are getting the first-line recommended treatment. We still have a long ways to go.

Another place where we’re innovative is with contingency management. I mentioned psychosocial treatments. Behavioral treatment is very effective and yet is not often used in treatment of substance use disorders; but it works. And even better than that, it is fun.

Let me try to explain what this means. It’s based on the idea that the benefits of using drugs are immediate, and the benefits of staying sober take a long time to realize. And it is that difference that makes early recovery so challenging because, if someone has a craving for alcohol or another drug, they can satisfy that craving immediately and then have to pay the price, though, of health consequences or financial consequences or legal consequences from that alcohol or drug use.

On the other hand, staying sober is tough. But it takes a long time to put one’s life back together, to get one’s chronic health conditions that have been caused or made worse by the drug use back together. And the idea behind contingency management is to give immediate rewards early in recovery to keep folks engaged long enough to start realizing some of the longer-term benefits of recovery.

So the way this works, we use what we call the fishbowl model of contingency management. And we started with stimulant use disorders, which is one of the substance use disorders for which there’s no strong evidence for a medication that works; but this particular psychosocial intervention works very well. So patients come to the clinic twice a week, give a urine specimen for drug screen; and, based on those test results, if their test is negative and they haven’t used any stimulants, then they get a draw from the fishbowl, which is filled with slips of paper. Half of the slips of paper say, “Good job! Keep up the good work,” or something encouraging like that. And half of the slips of paper have a prize associated with them, and it could be a small prize like $1 or $5 for exchange at the VA Canteen store, or it could be a larger prize like $100 or $200. Of course, the less expensive prizes are more common than the more expensive prizes; but just that immediate reward can make such a difference.

With the first negative urine drug screen, you get 1 draw from the fishbowl. The second one in a row, you get 2; and so it goes that the longer you stay sober, the more chances you have for winning a prize. And this treatment can go on for as long as the veteran wants to continue for up to 12 weeks. Usually by 12 weeks, folks’ health and their lives are coming back together; and so there’s many more rewards for staying sober than just the draws from the fishbowl. And what we find is folks who get a good start with contingency management tend to stay on that trajectory towards recovery.

And this has been a wonderful partnership between the Center of Excellence for Substance Abuse Treatment and Education in Philadelphia and the VA Canteen Service, who has generously donated canteen coupons. So it doesn’t cost the medical center anything to offer these prizes, and we’ve had just some amazing results.

To listen to the unedited interview here

While much of private health care in the U.S. is only beginning to confront the burgeoning opioid epidemic, the VA has a long-standing commitment to providing treatment to veterans struggling with substance use disorders. To understand the scope of the challenge and the VA’s approach, Federal Practitioner Editor-in-Chief Cynthia M.A. Geppert, MD, talked with Karen Drexler, MD, national mental health program director, substance use disorders. Dr. Drexler served in the U.S. Air Force for 8 years before joining the Atlanta VAMC in Georgia, where she directed the substance abuse treatment program. She is an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University. In 2014, Dr. Drexler was named deputy mental health program director, addictive disorders.

Editor-in-Chief Cynthia M.A. Geppert, MD. As national mental health program director for substance use disorders, what are the challenges facing VA substance use programs?

Karen Drexler, MD. The biggest challenge is the increasing demand for services. Veterans have been coming to the VA for mental health care in general and for substance use disorder treatment in particular. The most common substance use disorder that we treat in addition to tobacco is alcohol use disorder, and the demand for alcohol use disorder treatment continues to grow.

Also, with the opioid crisis, there’s increasing demand for opioid use disorder treatments, including what we recommend as first-line treatment, which is medication-assisted treatment using buprenorphine or methadone, or injectable naltrexone as a second-line treatment. Gearing up with medication-assisted treatment for both alcohol and opioid use disorders is probably our biggest challenge.

Dr. Geppert. What were the most important accomplishments of the VA substance abuse programs over the past 5 years?

Dr. Drexler. There have been a lot! First of all, one of the things I love about practicing within the VA is that we are an integrated health care system. When I talk with colleagues in the Emory system here in Atlanta and across the country, oftentimes mental health and substance use disorders are isolated. The funding streams through the public sector come in different ways. Third-party payers have carve-outs for behavioral health.

It’s really wonderful to be able to collaborate with my colleagues in primary care, medical specialty care, and general mental health care, to provide a holistic and team-based approach to our patients who have both medical and substance use disorder problems and often co-occurring mental illness. As we’ve moved from a hospital-based system to more outpatient [care], the VA continues to be able to collaborate through our electronic health records as well as just being able to pick up the phone or send a [Microsoft] Lync message or an Outlook encrypted e-mail to help facilitate that coordinated care.

Another accomplishment has been to [develop] policy. It’s one of our challenges, but it’s also an accomplishment even at this early stage. In 2008, we issued the Uniform Mental Health Services benefits package as part of VHA Handbook on Mental Health Services. From that very beginning, we have included medication-assisted therapy when indicated for veterans with substance use disorders.

Now, we also know there’s a lot of variability in the system, so not every facility is providing these indicated treatments yet; but at least it’s part of our policy, and it’s been a focus of ongoing quality improvement to make these treatments available for veterans when they need them.

Dr. Geppert. We’ve heard a lot lately about the CDC guidelines for prescribing opiates for chronic pain that were published earlier this year. How do you see these guidelines affecting the VA Opiate Safety Initiative? Do you see any important contradictions between current VA policy and these new guidelines?

Dr. Drexler. Yes—not necessarily with policy but with our VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines from 2010 and the new CDC guidelines. There’s a shift in emphasis. The 2010 VA/DoD guidelines were maybe a little too optimistic about the safety of opioids for chronic, noncancer pain. As time goes on, more evidence is mounting of the potential harms, including from my perspective, the risk of developing an opioid use disorder when taking opioid analgesics as prescribed.

In the 1990s and the early 2000s, experts in the field reassured us. They told us all—patients and providers alike—that if opioid analgesics were taken as prescribed for legitimate pain by people who didn’t have a previous history of a substance use disorder, they could take them and would not be at risk for becoming addicted. We now know that’s simply not true. Patients who take these medicines as prescribed by their providers end up developing tolerance, developing hyperalgesia, needing more and more medication to get the desired effect, and crossing that line from just physiologic tolerance to developing an opioid use disorder.

We now have better guidelines about where that risk increases. We have some data from observational studies that patients who are maintained on opioid analgesics that are < 50 mg of daily morphine equivalent dose (MED) tend not to have as high a risk of overdose as those who are maintained on more, but the risk of developing an opioid use disorder actually is not insignificant even below 50 mg MED.

The key for developing an opioid use disorder is how long the patient is on the treatment. For patients who take opioid analgesics for < 90 days—again, these are observational studies—very few went on to develop opioid use disorder. However, those who took it for > 90 days, even those who were maintained on < 36 mg MED, had a significantly increased risk of developing an opioid use disorder. And for those who were on the higher dose, say, > 120 mg MED, the risk went up to 122-fold.

We just don’t see those kinds of odds ratios elsewhere in medicine. You know, we address risk factors when it increases the risk by 50%, but this is 122-fold.

Dr. Geppert. Pain as the fifth vital sign had a dark side there. Is there anything else you want to say to us about the Opiate Safety Initiative?

Dr. Drexler. I think it’s been incredibly successful; but like any change, there are unintended consequences and challenges with any change, even a good change. One of the things that has been a good change is raising awareness that opioids are not the answer for chronic pain. We have better evidence that self-care strategies (movement, exercise, physical therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy for pain) help folks learn strategies for addressing automatic alarming thoughts about their pain—that it’s signaling something terrible when, really, it’s not. There are things that people can do to manage pain on their own. Those [strategies] are safer, and we have better evidence that they are effective than we have for opioids taken past 12 weeks.

Dr. Geppert. It’s really a paradigm shift in understanding. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 has proposed to allow some nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. What role does the VA see for PAs and NPs in patient care for veterans with substance use disorders with medication-assisted therapy, and do you think that’ll involve prescribing buprenorphine?

Dr. Drexler. One of the things that I love about practicing within the VA is working within an interdisciplinary team and having that team-based approach. When we work together, our results far outshine anything that any one of us could do separately. I am very much looking forward to being able to provide or collaborate with other federal partners like the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] to provide the training for VA NPs and PAs who are able to prescribe controlled substances with their state licensure to provide buprenorphine for our patients.

Even without that prescriptive authority, NPs and PAs are already important partners and members of the interdisciplinary team who are managing patients and providing the evidence-based counseling, the monitoring, following up urine drug screen results, and doing a lot of the management, but not signing the prescription that’s being provided now by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act-waivered physicians. But SAMHSA has yet to define what the 24 hours of training will be that NPs and PAs will need to complete in order to apply for their U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration waiver, but we’re very much looking forward to it. And I am in contact with colleagues at SAMHSA, and they promise me they will keep me informed when they have the regulations set out for us to follow.

Dr. Geppert. The new VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Substance Use Disorders were published earlier this year. Could you give us an overview of the guidelines and what’s significant for most of our providers in the field?

Dr. Drexler. I’m very excited about the guidelines. One of the first things you should know is that they are very evidence based. If you’ve been practicing medicine as long as I have, you’ll remember, when the first clinical practice guidelines came out, they were expert opinion. They got some of the leading practitioners and researchers in the country together, put them in a room, and said, “What do you think people should do to treat this disorder?” Over time, clinical practice guidelines have become more evidence based; and the VA/DoD collaborative follows a highly respected methodology called the GRADE methodology.

Let me explain that just briefly. It means that our recommendations are based on systematic reviews of the literature. We all have our own screens and filters and our favorite studies. And so, if you get a bunch of experts together, they may not have as dispassionate a view of the entire literature as when you do a systematic review; and that’s what we started with.

We followed a specific methodology as well that took into account not only the strength of the evidence where the gold standard is a randomized, controlled clinical trial and, even better than that, a meta-analysis of multiple clinical trials. And for our recommendations, the strength of the evidence was, by far, supported mostly by clinical trials or meta-analyses. So, when you look at the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines, and I hope you will, you can feel confident that what we’re recommending is not just pulled out of the sky or some idiosyncratic favorite thing that Karen Drexler likes. It’s really based on good, strong clinical evidence.

We went from the previous version that had over 160 recommendations. We distilled them down to 36, and those 36 recommendations cover everything from prevention in primary care settings to stabilization and withdrawal management for alcohol and sedatives and opioids, and then treatment or rehabilitation of the 4 most common substance use disorders and then some general principles (Table 1).

There’s good evidence that what we’re doing in VA with screening in primary care every year using the AUDIT-C [Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption] is making a difference (Table 2). That folks who screen positive for at-risk alcohol use are very likely to respond to a brief intervention by their health care provider and reduce their alcohol consumption to safe levels, where they’re not likely to go on to develop an addiction to the alcohol or to develop medical complications from heavy alcohol use.

After screening, then, if someone does develop a substance use disorder, we have evidence-based treatments, both medications for 2 of our most common disorders and psychosocial interventions for all 4 most common disorders after tobacco. And I don’t exclude tobacco because it’s not important; it’s incredibly important, but it gets its own clinical practice guidelines. So, with our limited budget, we just addressed the other 10 substances….

For alcohol we have great evidence for 5 different medications and for 6 different psychosocial approaches. It is the most common substance use disorder, but we also have a whole menu of different treatments that folks can choose from, everything from naltrexone—oral naltrexone is the most common medication that we prescribe—but also acamprosate; disulfiram; extended-release injectable naltrexone. Topiramate, interestingly, is not FDA approved for that indication, but we have found good evidence from clinical trials supporting topiramate, so we strongly recommend it. If any of those are not acceptable or not tolerated or ineffective, then we also have some evidence to support gabapentin as well. So we have a strong recommendation for the first ones and a suggestion for gabapentin if it’s clinically indicated.

In terms of psychosocial approaches, [we recommend] everything from motivation enhancement therapy or motivational interviewing; cognitive-behavioral therapy; 12-step facilitation, which is a structured way of getting folks to get more active in Alcoholics Anonymous; behavioral approaches like community reinforcement approach or contingency management.

For opioid use disorder, interestingly, we found good, strong evidence that medication-assisted treatments work but no evidence for any psychosocial intervention without medication. Let me say that again because, nationwide, the most common treatment that’s provided for opioid use disorder, for any substance use disorder, is a psychosocial intervention—talking therapy alone.

For all of the medicines for alcohol use disorder, the medicine improved upon talking therapy alone. For opioid use disorder, medication helps people stay sober; it retains them in treatment; it saves lives. But for talking therapy without medication, we have found insufficient evidence to recommend any particular treatment.

Dr. Geppert. Incredible. That leads to my next question: One of the most challenging issues facing primary care practitioners is how to manage patients who are on chronic opiate therapy but also use medical marijuana in the increasing number of states where it’s legal. Do you have some advice on how to approach these situations?

Dr. Drexler. It’s a great question, and it’s one I’m sure more and more VA practitioners are grappling with. By our policy, we do not exclude veterans who are taking medical marijuana from any VA services, and we encourage the veterans to speak up about it so that it can be considered as part of their treatment plan.

By policy, however, VA practitioners do not fill out forms for state-approved marijuana. Marijuana is still a Schedule I controlled substance by federal law, so it’s a very interesting legal situation where it’s illegal federally; but some states have passed laws making it legal by state law. It will be interesting to see how this plays out over the next few years.

But in that situation—and really, this is our policy, in general for substance use disorders—a patient having a substance use disorder should not be precluded or excluded from getting treatment for other medical conditions. Similarly, other medical conditions shouldn’t exclude patients from getting treatment for their substance use disorder. However, the best treatment comes when we look at the whole person and try to take both things into account.

In the same way that patients can become addicted to their opioid pain medicines, patients can become addicted to medical marijuana. So the marijuana use needs to be evaluated objectively; and whether or not they have a form, just like whether or not someone has a prescription for their opioid that may be causing them problems, that needs to be taken into account in the treatment plan; and the treatment needs to be individualized.

Dr. Geppert. What in VA substance use disorder programs and treatment do you think is especially innovative when compared to the community?

Dr. Drexler. One of the places where I think the VA is well ahead of our colleagues elsewhere in health care is…from SAIL [Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning] metrics. About 34% or 35% of veterans who are diagnosed clinically within our system with opioid use disorders are receiving medication-assisted therapy either with buprenorphine, methadone, or extended-release injectable naltrexone. When you look at the SAMHSA survey, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the percentage of patients in the community who meet criteria for a substance use disorder [who] actually receive treatment is more like 12%. We have no numbers from SAMHSA about what percentage are receiving medication-assisted treatment. They don’t ask. In that way, even though we have a long ways to go, we’re ahead of the curve when it comes to medication-assisted treatment. But the demand is growing, we’re going to have to keep working hard to keep up and to get ahead at this. When I think about it compared to other chronic illnesses, only 35% of our patients are getting the first-line recommended treatment. We still have a long ways to go.

Another place where we’re innovative is with contingency management. I mentioned psychosocial treatments. Behavioral treatment is very effective and yet is not often used in treatment of substance use disorders; but it works. And even better than that, it is fun.

Let me try to explain what this means. It’s based on the idea that the benefits of using drugs are immediate, and the benefits of staying sober take a long time to realize. And it is that difference that makes early recovery so challenging because, if someone has a craving for alcohol or another drug, they can satisfy that craving immediately and then have to pay the price, though, of health consequences or financial consequences or legal consequences from that alcohol or drug use.

On the other hand, staying sober is tough. But it takes a long time to put one’s life back together, to get one’s chronic health conditions that have been caused or made worse by the drug use back together. And the idea behind contingency management is to give immediate rewards early in recovery to keep folks engaged long enough to start realizing some of the longer-term benefits of recovery.

So the way this works, we use what we call the fishbowl model of contingency management. And we started with stimulant use disorders, which is one of the substance use disorders for which there’s no strong evidence for a medication that works; but this particular psychosocial intervention works very well. So patients come to the clinic twice a week, give a urine specimen for drug screen; and, based on those test results, if their test is negative and they haven’t used any stimulants, then they get a draw from the fishbowl, which is filled with slips of paper. Half of the slips of paper say, “Good job! Keep up the good work,” or something encouraging like that. And half of the slips of paper have a prize associated with them, and it could be a small prize like $1 or $5 for exchange at the VA Canteen store, or it could be a larger prize like $100 or $200. Of course, the less expensive prizes are more common than the more expensive prizes; but just that immediate reward can make such a difference.

With the first negative urine drug screen, you get 1 draw from the fishbowl. The second one in a row, you get 2; and so it goes that the longer you stay sober, the more chances you have for winning a prize. And this treatment can go on for as long as the veteran wants to continue for up to 12 weeks. Usually by 12 weeks, folks’ health and their lives are coming back together; and so there’s many more rewards for staying sober than just the draws from the fishbowl. And what we find is folks who get a good start with contingency management tend to stay on that trajectory towards recovery.

And this has been a wonderful partnership between the Center of Excellence for Substance Abuse Treatment and Education in Philadelphia and the VA Canteen Service, who has generously donated canteen coupons. So it doesn’t cost the medical center anything to offer these prizes, and we’ve had just some amazing results.

To listen to the unedited interview here

While much of private health care in the U.S. is only beginning to confront the burgeoning opioid epidemic, the VA has a long-standing commitment to providing treatment to veterans struggling with substance use disorders. To understand the scope of the challenge and the VA’s approach, Federal Practitioner Editor-in-Chief Cynthia M.A. Geppert, MD, talked with Karen Drexler, MD, national mental health program director, substance use disorders. Dr. Drexler served in the U.S. Air Force for 8 years before joining the Atlanta VAMC in Georgia, where she directed the substance abuse treatment program. She is an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University. In 2014, Dr. Drexler was named deputy mental health program director, addictive disorders.

Editor-in-Chief Cynthia M.A. Geppert, MD. As national mental health program director for substance use disorders, what are the challenges facing VA substance use programs?

Karen Drexler, MD. The biggest challenge is the increasing demand for services. Veterans have been coming to the VA for mental health care in general and for substance use disorder treatment in particular. The most common substance use disorder that we treat in addition to tobacco is alcohol use disorder, and the demand for alcohol use disorder treatment continues to grow.

Also, with the opioid crisis, there’s increasing demand for opioid use disorder treatments, including what we recommend as first-line treatment, which is medication-assisted treatment using buprenorphine or methadone, or injectable naltrexone as a second-line treatment. Gearing up with medication-assisted treatment for both alcohol and opioid use disorders is probably our biggest challenge.

Dr. Geppert. What were the most important accomplishments of the VA substance abuse programs over the past 5 years?

Dr. Drexler. There have been a lot! First of all, one of the things I love about practicing within the VA is that we are an integrated health care system. When I talk with colleagues in the Emory system here in Atlanta and across the country, oftentimes mental health and substance use disorders are isolated. The funding streams through the public sector come in different ways. Third-party payers have carve-outs for behavioral health.

It’s really wonderful to be able to collaborate with my colleagues in primary care, medical specialty care, and general mental health care, to provide a holistic and team-based approach to our patients who have both medical and substance use disorder problems and often co-occurring mental illness. As we’ve moved from a hospital-based system to more outpatient [care], the VA continues to be able to collaborate through our electronic health records as well as just being able to pick up the phone or send a [Microsoft] Lync message or an Outlook encrypted e-mail to help facilitate that coordinated care.

Another accomplishment has been to [develop] policy. It’s one of our challenges, but it’s also an accomplishment even at this early stage. In 2008, we issued the Uniform Mental Health Services benefits package as part of VHA Handbook on Mental Health Services. From that very beginning, we have included medication-assisted therapy when indicated for veterans with substance use disorders.

Now, we also know there’s a lot of variability in the system, so not every facility is providing these indicated treatments yet; but at least it’s part of our policy, and it’s been a focus of ongoing quality improvement to make these treatments available for veterans when they need them.

Dr. Geppert. We’ve heard a lot lately about the CDC guidelines for prescribing opiates for chronic pain that were published earlier this year. How do you see these guidelines affecting the VA Opiate Safety Initiative? Do you see any important contradictions between current VA policy and these new guidelines?

Dr. Drexler. Yes—not necessarily with policy but with our VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines from 2010 and the new CDC guidelines. There’s a shift in emphasis. The 2010 VA/DoD guidelines were maybe a little too optimistic about the safety of opioids for chronic, noncancer pain. As time goes on, more evidence is mounting of the potential harms, including from my perspective, the risk of developing an opioid use disorder when taking opioid analgesics as prescribed.

In the 1990s and the early 2000s, experts in the field reassured us. They told us all—patients and providers alike—that if opioid analgesics were taken as prescribed for legitimate pain by people who didn’t have a previous history of a substance use disorder, they could take them and would not be at risk for becoming addicted. We now know that’s simply not true. Patients who take these medicines as prescribed by their providers end up developing tolerance, developing hyperalgesia, needing more and more medication to get the desired effect, and crossing that line from just physiologic tolerance to developing an opioid use disorder.

We now have better guidelines about where that risk increases. We have some data from observational studies that patients who are maintained on opioid analgesics that are < 50 mg of daily morphine equivalent dose (MED) tend not to have as high a risk of overdose as those who are maintained on more, but the risk of developing an opioid use disorder actually is not insignificant even below 50 mg MED.

The key for developing an opioid use disorder is how long the patient is on the treatment. For patients who take opioid analgesics for < 90 days—again, these are observational studies—very few went on to develop opioid use disorder. However, those who took it for > 90 days, even those who were maintained on < 36 mg MED, had a significantly increased risk of developing an opioid use disorder. And for those who were on the higher dose, say, > 120 mg MED, the risk went up to 122-fold.

We just don’t see those kinds of odds ratios elsewhere in medicine. You know, we address risk factors when it increases the risk by 50%, but this is 122-fold.

Dr. Geppert. Pain as the fifth vital sign had a dark side there. Is there anything else you want to say to us about the Opiate Safety Initiative?

Dr. Drexler. I think it’s been incredibly successful; but like any change, there are unintended consequences and challenges with any change, even a good change. One of the things that has been a good change is raising awareness that opioids are not the answer for chronic pain. We have better evidence that self-care strategies (movement, exercise, physical therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy for pain) help folks learn strategies for addressing automatic alarming thoughts about their pain—that it’s signaling something terrible when, really, it’s not. There are things that people can do to manage pain on their own. Those [strategies] are safer, and we have better evidence that they are effective than we have for opioids taken past 12 weeks.

Dr. Geppert. It’s really a paradigm shift in understanding. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 has proposed to allow some nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. What role does the VA see for PAs and NPs in patient care for veterans with substance use disorders with medication-assisted therapy, and do you think that’ll involve prescribing buprenorphine?

Dr. Drexler. One of the things that I love about practicing within the VA is working within an interdisciplinary team and having that team-based approach. When we work together, our results far outshine anything that any one of us could do separately. I am very much looking forward to being able to provide or collaborate with other federal partners like the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] to provide the training for VA NPs and PAs who are able to prescribe controlled substances with their state licensure to provide buprenorphine for our patients.

Even without that prescriptive authority, NPs and PAs are already important partners and members of the interdisciplinary team who are managing patients and providing the evidence-based counseling, the monitoring, following up urine drug screen results, and doing a lot of the management, but not signing the prescription that’s being provided now by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act-waivered physicians. But SAMHSA has yet to define what the 24 hours of training will be that NPs and PAs will need to complete in order to apply for their U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration waiver, but we’re very much looking forward to it. And I am in contact with colleagues at SAMHSA, and they promise me they will keep me informed when they have the regulations set out for us to follow.

Dr. Geppert. The new VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Substance Use Disorders were published earlier this year. Could you give us an overview of the guidelines and what’s significant for most of our providers in the field?

Dr. Drexler. I’m very excited about the guidelines. One of the first things you should know is that they are very evidence based. If you’ve been practicing medicine as long as I have, you’ll remember, when the first clinical practice guidelines came out, they were expert opinion. They got some of the leading practitioners and researchers in the country together, put them in a room, and said, “What do you think people should do to treat this disorder?” Over time, clinical practice guidelines have become more evidence based; and the VA/DoD collaborative follows a highly respected methodology called the GRADE methodology.

Let me explain that just briefly. It means that our recommendations are based on systematic reviews of the literature. We all have our own screens and filters and our favorite studies. And so, if you get a bunch of experts together, they may not have as dispassionate a view of the entire literature as when you do a systematic review; and that’s what we started with.

We followed a specific methodology as well that took into account not only the strength of the evidence where the gold standard is a randomized, controlled clinical trial and, even better than that, a meta-analysis of multiple clinical trials. And for our recommendations, the strength of the evidence was, by far, supported mostly by clinical trials or meta-analyses. So, when you look at the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines, and I hope you will, you can feel confident that what we’re recommending is not just pulled out of the sky or some idiosyncratic favorite thing that Karen Drexler likes. It’s really based on good, strong clinical evidence.

We went from the previous version that had over 160 recommendations. We distilled them down to 36, and those 36 recommendations cover everything from prevention in primary care settings to stabilization and withdrawal management for alcohol and sedatives and opioids, and then treatment or rehabilitation of the 4 most common substance use disorders and then some general principles (Table 1).

There’s good evidence that what we’re doing in VA with screening in primary care every year using the AUDIT-C [Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption] is making a difference (Table 2). That folks who screen positive for at-risk alcohol use are very likely to respond to a brief intervention by their health care provider and reduce their alcohol consumption to safe levels, where they’re not likely to go on to develop an addiction to the alcohol or to develop medical complications from heavy alcohol use.

After screening, then, if someone does develop a substance use disorder, we have evidence-based treatments, both medications for 2 of our most common disorders and psychosocial interventions for all 4 most common disorders after tobacco. And I don’t exclude tobacco because it’s not important; it’s incredibly important, but it gets its own clinical practice guidelines. So, with our limited budget, we just addressed the other 10 substances….

For alcohol we have great evidence for 5 different medications and for 6 different psychosocial approaches. It is the most common substance use disorder, but we also have a whole menu of different treatments that folks can choose from, everything from naltrexone—oral naltrexone is the most common medication that we prescribe—but also acamprosate; disulfiram; extended-release injectable naltrexone. Topiramate, interestingly, is not FDA approved for that indication, but we have found good evidence from clinical trials supporting topiramate, so we strongly recommend it. If any of those are not acceptable or not tolerated or ineffective, then we also have some evidence to support gabapentin as well. So we have a strong recommendation for the first ones and a suggestion for gabapentin if it’s clinically indicated.

In terms of psychosocial approaches, [we recommend] everything from motivation enhancement therapy or motivational interviewing; cognitive-behavioral therapy; 12-step facilitation, which is a structured way of getting folks to get more active in Alcoholics Anonymous; behavioral approaches like community reinforcement approach or contingency management.

For opioid use disorder, interestingly, we found good, strong evidence that medication-assisted treatments work but no evidence for any psychosocial intervention without medication. Let me say that again because, nationwide, the most common treatment that’s provided for opioid use disorder, for any substance use disorder, is a psychosocial intervention—talking therapy alone.

For all of the medicines for alcohol use disorder, the medicine improved upon talking therapy alone. For opioid use disorder, medication helps people stay sober; it retains them in treatment; it saves lives. But for talking therapy without medication, we have found insufficient evidence to recommend any particular treatment.

Dr. Geppert. Incredible. That leads to my next question: One of the most challenging issues facing primary care practitioners is how to manage patients who are on chronic opiate therapy but also use medical marijuana in the increasing number of states where it’s legal. Do you have some advice on how to approach these situations?

Dr. Drexler. It’s a great question, and it’s one I’m sure more and more VA practitioners are grappling with. By our policy, we do not exclude veterans who are taking medical marijuana from any VA services, and we encourage the veterans to speak up about it so that it can be considered as part of their treatment plan.

By policy, however, VA practitioners do not fill out forms for state-approved marijuana. Marijuana is still a Schedule I controlled substance by federal law, so it’s a very interesting legal situation where it’s illegal federally; but some states have passed laws making it legal by state law. It will be interesting to see how this plays out over the next few years.

But in that situation—and really, this is our policy, in general for substance use disorders—a patient having a substance use disorder should not be precluded or excluded from getting treatment for other medical conditions. Similarly, other medical conditions shouldn’t exclude patients from getting treatment for their substance use disorder. However, the best treatment comes when we look at the whole person and try to take both things into account.

In the same way that patients can become addicted to their opioid pain medicines, patients can become addicted to medical marijuana. So the marijuana use needs to be evaluated objectively; and whether or not they have a form, just like whether or not someone has a prescription for their opioid that may be causing them problems, that needs to be taken into account in the treatment plan; and the treatment needs to be individualized.

Dr. Geppert. What in VA substance use disorder programs and treatment do you think is especially innovative when compared to the community?

Dr. Drexler. One of the places where I think the VA is well ahead of our colleagues elsewhere in health care is…from SAIL [Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning] metrics. About 34% or 35% of veterans who are diagnosed clinically within our system with opioid use disorders are receiving medication-assisted therapy either with buprenorphine, methadone, or extended-release injectable naltrexone. When you look at the SAMHSA survey, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the percentage of patients in the community who meet criteria for a substance use disorder [who] actually receive treatment is more like 12%. We have no numbers from SAMHSA about what percentage are receiving medication-assisted treatment. They don’t ask. In that way, even though we have a long ways to go, we’re ahead of the curve when it comes to medication-assisted treatment. But the demand is growing, we’re going to have to keep working hard to keep up and to get ahead at this. When I think about it compared to other chronic illnesses, only 35% of our patients are getting the first-line recommended treatment. We still have a long ways to go.

Another place where we’re innovative is with contingency management. I mentioned psychosocial treatments. Behavioral treatment is very effective and yet is not often used in treatment of substance use disorders; but it works. And even better than that, it is fun.

Let me try to explain what this means. It’s based on the idea that the benefits of using drugs are immediate, and the benefits of staying sober take a long time to realize. And it is that difference that makes early recovery so challenging because, if someone has a craving for alcohol or another drug, they can satisfy that craving immediately and then have to pay the price, though, of health consequences or financial consequences or legal consequences from that alcohol or drug use.

On the other hand, staying sober is tough. But it takes a long time to put one’s life back together, to get one’s chronic health conditions that have been caused or made worse by the drug use back together. And the idea behind contingency management is to give immediate rewards early in recovery to keep folks engaged long enough to start realizing some of the longer-term benefits of recovery.

So the way this works, we use what we call the fishbowl model of contingency management. And we started with stimulant use disorders, which is one of the substance use disorders for which there’s no strong evidence for a medication that works; but this particular psychosocial intervention works very well. So patients come to the clinic twice a week, give a urine specimen for drug screen; and, based on those test results, if their test is negative and they haven’t used any stimulants, then they get a draw from the fishbowl, which is filled with slips of paper. Half of the slips of paper say, “Good job! Keep up the good work,” or something encouraging like that. And half of the slips of paper have a prize associated with them, and it could be a small prize like $1 or $5 for exchange at the VA Canteen store, or it could be a larger prize like $100 or $200. Of course, the less expensive prizes are more common than the more expensive prizes; but just that immediate reward can make such a difference.

With the first negative urine drug screen, you get 1 draw from the fishbowl. The second one in a row, you get 2; and so it goes that the longer you stay sober, the more chances you have for winning a prize. And this treatment can go on for as long as the veteran wants to continue for up to 12 weeks. Usually by 12 weeks, folks’ health and their lives are coming back together; and so there’s many more rewards for staying sober than just the draws from the fishbowl. And what we find is folks who get a good start with contingency management tend to stay on that trajectory towards recovery.

And this has been a wonderful partnership between the Center of Excellence for Substance Abuse Treatment and Education in Philadelphia and the VA Canteen Service, who has generously donated canteen coupons. So it doesn’t cost the medical center anything to offer these prizes, and we’ve had just some amazing results.

To listen to the unedited interview here