User login

Every year in the U.S., more than 435,000 people die of illnesses related to tobacco use.1 The CDC reported that from 2012 to 2013, 21.3% of adults used some form of tobacco daily or on some days.2 Veterans are not excluded from these numbers: A 2005 survey found 22.2% of VA patients were current smokers, and 71.2% of VA patients had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their life.3

Military personnel have a higher propensity to be in situations that increase the risk of tobacco use than the general population does.3,4 These situations include alternating between periods of high stress and boredom, separation from loved ones, perceived camaraderie involved with tobacco use, and the limitation of healthier coping mechanisms.3,4 Stress and boredom have been cited as the top reasons for initiating tobacco use when deployed.3,4 Furthermore, once military personnel return from deployment, they may have difficulty quitting tobacco due to depression, sleeplessness, change in the structure of everyday life, or a second deployment.4

In 2009 Bondurant and Wedge predicted that the VA would spend $30.9 billion in preventable smoking-related expenditures by 2024.3 The negative health effects and the financial impact of tobacco make cessation programs an important investment for the VA.

In 2012, the CDC reported that 70% of veterans want to quit tobacco; therefore, veterans likely would be interested in tobacco cessation programs.4 Reasons veterans noted for quitting included family, changes in the social norm, better overall health, and better ability to breathe.4 Veterans also identified that tobacco cessation programs with convenience, personalization, reduced-cost medications, and peer support would be most helpful.4

According to a 2008 tobacco use and dependence guideline update, the most effective therapy for quitting tobacco is counseling plus pharmacotherapy.1 According to the guideline, the number of counseling sessions combined with pharmacotherapy is strongly related to the likelihood of quitting.1 A number of studies also have shown that telephone counseling is effective for tobacco cessation.5 However, a previous study in veterans found that scheduled face-to-face counseling sessions may be more effective than telephone counseling.6 Dent and colleagues found a statistically significant quit rate at 6 months of 28% in the face-to-face group vs 11.8% in the telephone group.6

After reviewing the guidelines, analyzing the studies, and learning what veterans find most helpful in tobacco cessation programs, the Sioux Falls VA Health Care System (SFVAHCS) in South Dakota took a unique approach to tobacco cessation. In 2012, SFVAHCS implemented a tobacco cessation drop-in group medical appointment (DIGMA) to improve tobacco quit rates. The DIGMA is a 1-hour, educational supportive clinic that allows veterans to drop in during any class anytime, regardless of their tobacco use status. This clinic mostly serves outpatients; however, inpatients also are welcome. Patients are informed of the DIGMA by a health care provider (HCP) or patient information flyers posted throughout SFVAHCS.

The DIGMA takes place once a week in a classroom next to a primary care waiting area, making it easily accessible. During the DIGMA, an HCP, such as a nurse or physician, provides behavioral education. VA materials (Primary Care and Tobacco Cessation Handbook and My Tobacco Cessation Workbook designed by Julianne Himstreet, PharmD, BCPS) are used to guide classes.7,8 These books address barriers to quitting, coping with nicotine withdrawal, planning for quit day, handling tobacco cravings, watching out for triggers, and staying tobacco free.7,8 Clinical pharmacists also are present at the DIGMA for patients who want to start or continue pharmacotherapy. The pharmacists can prescribe tobacco cessation medications and follow up on the success or adverse effects (AEs) of therapy.

The purpose of this study was to examine how a voluntary, drop-in, face-to-face tobacco cessation clinic impacts tobacco quit rates in veterans receiving pharmacotherapy.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed for all study site outpatients started on pharmacotherapy for tobacco cessation between September 1, 2012 and August 31, 2013, as determined by pharmacy dispensing records. Two groups were evaluated in this study: the pharmacotherapy-only (PO) group and the DIGMA group. Pharmacotherapy was most often prescribed by an HCP in the PO group. Other prescribers may have included pharmacists, mental health providers, and hospitalists. The second group was the DIGMA group, which included patients who were on tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy and attended at least 1 DIGMA class within a year of starting pharmacotherapy.

For this study, pharmacotherapy included nicotine gum, nicotine lozenge, nicotine patch, bupropion, varenicline, and any combination of these medications. Patients were excluded if they died, moved, or were lost to follow-up within 1 year of starting pharmacotherapy for a new quit attempt; were not at the beginning of a quit attempt; or were taking bupropion for mood or depression only.

One hundred thirty-six patients attended the DIGMA during the study period, but only 49 patients met the inclusion criteria. Patients also were excluded because they were not at the beginning of a quit attempt, were not receiving pharmacotherapy, or were not seen by an HCP to assess tobacco status after receiving tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy.

A total of 1,807 patients were identified as potential candidates for the PO group. Once the DIGMA patients were identified, an equal number of patients were randomly chosen for the PO group. To ensure that the PO group was random, the patient list was alphabetized, and patients were selected if they met the PO inclusion criteria, starting at the top of the list and moving down until the needed number was met.

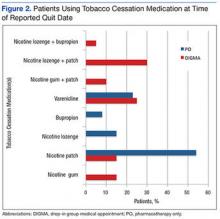

The primary endpoint was the tobacco quit rate within 1 year of starting pharmacotherapy for a new quit attempt. Tobacco use status was determined from the patient’s electronic medical record. A subgroup analysis was performed to determine the percentage of patients using each tobacco cessation medication or a combination of medications at the time of the reported quit date.

This study also looked at the number of DIGMA classes attended by patients who quit tobacco and the number of times patients switched pharmacotherapy during the 1-year time frame. A chi-square test was executed to evaluate the primary endpoint, and descriptive statistics were performed for the subgroup analysis. A P value of ≤ .05 was deemed significant.

Results

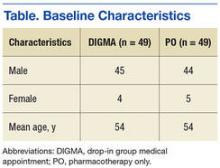

A total of 98 patients were included with 49 patients in each study arm. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups with an average age of 54 years in both groups (Table). As shown in Figure 1, 40.8% of patients in the DIGMA group quit tobacco compared with 26.5% in the PO group (P = .19).

Discussion

The tobacco quit rate of veterans on pharmacotherapy who attended at least 1 DIGMA class was higher than the quit rate of veterans on pharmacotherapy only. Although the difference between quit rates was not statistically significant, the difference was clinically important. Every time a patient quits tobacco, years of negative health consequences and cost to the health care system may be prevented. Patients who quit tobacco and continue to attend DIGMA classes also can provide support and advice to others who are trying to quit.

The study results also suggest that the tobacco cessation DIGMA provided personalized care to veterans, as demonstrated by patients in the DIGMA group switching pharmacotherapy and using combination therapy more often. Access to pharmacists who can prescribe medications, change therapy, and assist with AEs gave patients the opportunity to determine the most efficacious therapy. Pharmacists also are aware of the pros and cons of the different tobacco cessation medications and are able to help patients pick the best medication to start with or change to.

Patients in the DIGMA group who quit tobacco attended an average of 1.4 classes. Those who attended the DIGMA may have been inherently more motivated to quit tobacco. However, the unique design of the DIGMA may have better equipped patients to quit tobacco after just 1 or 2 classes.

Limitations

Overall, an average attendance of 1.4 classes is a limitation; previous studies have shown that quit rates have a positive correlation with the number of counseling sessions attended.1 Another limitation is the small sample size. In addition, statistical power was not calculated. Tobacco use was not consistently documented in patients’ charts by the HCP and may not have been addressed at every visit. Some patients who quit tobacco may have been missed due to the lack of documentation of tobacco use status. Last, because reviewing a patient chart ended once documentation of tobacco cessation was found, some patients may have relapsed after quitting.

The study site likely could have offered better notice of the presence of the DIGMA. Although flyers and advertisements were available and posted, some tobacco-using patients may not have been aware of the DIGMA. The SFVAHCS could increase awareness of the program if the pharmacy provided a DIGMA flyer with each outpatient tobacco cessation prescription.

A larger, prospective study would be beneficial and might show statistically significant differences in tobacco quit rates. Further studies that address whether the DIGMA helps patients who have quit tobacco to remain tobacco free are needed.

Conclusion

Patients who attended the tobacco cessation DIGMA received personalized care and had a higher tobacco quit rate than did patients receiving standard treatment. However, due to study limitations, these results should be confirmed with future studies.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Sioux Falls VA Health Care System in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical practice guidelines. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Health Resource and Services Administration website. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/buckets/treatingtobacco.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed July 8, 2016.

2. Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco product use among adults--United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):542-547.

3. Bondurant S, Wedge R, eds. Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009.

4. Gierisch JM, Straits-Tröster K, Calhoun PS, Beckham JC, Acheson S, Hamlett-Berry K. Tobacco use among Iraq- and Afghanistan-era veterans: a qualitative study of barriers, facilitators, and treatment p. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E58.

5. Chen T, Kazerooni R, Vannort E, et al. Comparison of an intensive pharmacist-managed telephone clinic with standard of care for tobacco cessation in a veteran population. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(4):512-520.

6. Dent LA, Harris KJ, Noonan CW. Randomized trial assessing the effectiveness of a pharmacist-delivered program for smoking cessation. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(2):194-201.

7. Himstreet J. My Tobacco Cessation Workbook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014.

8. Himstreet J. Primary Care & Tobacco Cessation Handbook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2013.

Every year in the U.S., more than 435,000 people die of illnesses related to tobacco use.1 The CDC reported that from 2012 to 2013, 21.3% of adults used some form of tobacco daily or on some days.2 Veterans are not excluded from these numbers: A 2005 survey found 22.2% of VA patients were current smokers, and 71.2% of VA patients had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their life.3

Military personnel have a higher propensity to be in situations that increase the risk of tobacco use than the general population does.3,4 These situations include alternating between periods of high stress and boredom, separation from loved ones, perceived camaraderie involved with tobacco use, and the limitation of healthier coping mechanisms.3,4 Stress and boredom have been cited as the top reasons for initiating tobacco use when deployed.3,4 Furthermore, once military personnel return from deployment, they may have difficulty quitting tobacco due to depression, sleeplessness, change in the structure of everyday life, or a second deployment.4

In 2009 Bondurant and Wedge predicted that the VA would spend $30.9 billion in preventable smoking-related expenditures by 2024.3 The negative health effects and the financial impact of tobacco make cessation programs an important investment for the VA.

In 2012, the CDC reported that 70% of veterans want to quit tobacco; therefore, veterans likely would be interested in tobacco cessation programs.4 Reasons veterans noted for quitting included family, changes in the social norm, better overall health, and better ability to breathe.4 Veterans also identified that tobacco cessation programs with convenience, personalization, reduced-cost medications, and peer support would be most helpful.4

According to a 2008 tobacco use and dependence guideline update, the most effective therapy for quitting tobacco is counseling plus pharmacotherapy.1 According to the guideline, the number of counseling sessions combined with pharmacotherapy is strongly related to the likelihood of quitting.1 A number of studies also have shown that telephone counseling is effective for tobacco cessation.5 However, a previous study in veterans found that scheduled face-to-face counseling sessions may be more effective than telephone counseling.6 Dent and colleagues found a statistically significant quit rate at 6 months of 28% in the face-to-face group vs 11.8% in the telephone group.6

After reviewing the guidelines, analyzing the studies, and learning what veterans find most helpful in tobacco cessation programs, the Sioux Falls VA Health Care System (SFVAHCS) in South Dakota took a unique approach to tobacco cessation. In 2012, SFVAHCS implemented a tobacco cessation drop-in group medical appointment (DIGMA) to improve tobacco quit rates. The DIGMA is a 1-hour, educational supportive clinic that allows veterans to drop in during any class anytime, regardless of their tobacco use status. This clinic mostly serves outpatients; however, inpatients also are welcome. Patients are informed of the DIGMA by a health care provider (HCP) or patient information flyers posted throughout SFVAHCS.

The DIGMA takes place once a week in a classroom next to a primary care waiting area, making it easily accessible. During the DIGMA, an HCP, such as a nurse or physician, provides behavioral education. VA materials (Primary Care and Tobacco Cessation Handbook and My Tobacco Cessation Workbook designed by Julianne Himstreet, PharmD, BCPS) are used to guide classes.7,8 These books address barriers to quitting, coping with nicotine withdrawal, planning for quit day, handling tobacco cravings, watching out for triggers, and staying tobacco free.7,8 Clinical pharmacists also are present at the DIGMA for patients who want to start or continue pharmacotherapy. The pharmacists can prescribe tobacco cessation medications and follow up on the success or adverse effects (AEs) of therapy.

The purpose of this study was to examine how a voluntary, drop-in, face-to-face tobacco cessation clinic impacts tobacco quit rates in veterans receiving pharmacotherapy.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed for all study site outpatients started on pharmacotherapy for tobacco cessation between September 1, 2012 and August 31, 2013, as determined by pharmacy dispensing records. Two groups were evaluated in this study: the pharmacotherapy-only (PO) group and the DIGMA group. Pharmacotherapy was most often prescribed by an HCP in the PO group. Other prescribers may have included pharmacists, mental health providers, and hospitalists. The second group was the DIGMA group, which included patients who were on tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy and attended at least 1 DIGMA class within a year of starting pharmacotherapy.

For this study, pharmacotherapy included nicotine gum, nicotine lozenge, nicotine patch, bupropion, varenicline, and any combination of these medications. Patients were excluded if they died, moved, or were lost to follow-up within 1 year of starting pharmacotherapy for a new quit attempt; were not at the beginning of a quit attempt; or were taking bupropion for mood or depression only.

One hundred thirty-six patients attended the DIGMA during the study period, but only 49 patients met the inclusion criteria. Patients also were excluded because they were not at the beginning of a quit attempt, were not receiving pharmacotherapy, or were not seen by an HCP to assess tobacco status after receiving tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy.

A total of 1,807 patients were identified as potential candidates for the PO group. Once the DIGMA patients were identified, an equal number of patients were randomly chosen for the PO group. To ensure that the PO group was random, the patient list was alphabetized, and patients were selected if they met the PO inclusion criteria, starting at the top of the list and moving down until the needed number was met.

The primary endpoint was the tobacco quit rate within 1 year of starting pharmacotherapy for a new quit attempt. Tobacco use status was determined from the patient’s electronic medical record. A subgroup analysis was performed to determine the percentage of patients using each tobacco cessation medication or a combination of medications at the time of the reported quit date.

This study also looked at the number of DIGMA classes attended by patients who quit tobacco and the number of times patients switched pharmacotherapy during the 1-year time frame. A chi-square test was executed to evaluate the primary endpoint, and descriptive statistics were performed for the subgroup analysis. A P value of ≤ .05 was deemed significant.

Results

A total of 98 patients were included with 49 patients in each study arm. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups with an average age of 54 years in both groups (Table). As shown in Figure 1, 40.8% of patients in the DIGMA group quit tobacco compared with 26.5% in the PO group (P = .19).

Discussion

The tobacco quit rate of veterans on pharmacotherapy who attended at least 1 DIGMA class was higher than the quit rate of veterans on pharmacotherapy only. Although the difference between quit rates was not statistically significant, the difference was clinically important. Every time a patient quits tobacco, years of negative health consequences and cost to the health care system may be prevented. Patients who quit tobacco and continue to attend DIGMA classes also can provide support and advice to others who are trying to quit.

The study results also suggest that the tobacco cessation DIGMA provided personalized care to veterans, as demonstrated by patients in the DIGMA group switching pharmacotherapy and using combination therapy more often. Access to pharmacists who can prescribe medications, change therapy, and assist with AEs gave patients the opportunity to determine the most efficacious therapy. Pharmacists also are aware of the pros and cons of the different tobacco cessation medications and are able to help patients pick the best medication to start with or change to.

Patients in the DIGMA group who quit tobacco attended an average of 1.4 classes. Those who attended the DIGMA may have been inherently more motivated to quit tobacco. However, the unique design of the DIGMA may have better equipped patients to quit tobacco after just 1 or 2 classes.

Limitations

Overall, an average attendance of 1.4 classes is a limitation; previous studies have shown that quit rates have a positive correlation with the number of counseling sessions attended.1 Another limitation is the small sample size. In addition, statistical power was not calculated. Tobacco use was not consistently documented in patients’ charts by the HCP and may not have been addressed at every visit. Some patients who quit tobacco may have been missed due to the lack of documentation of tobacco use status. Last, because reviewing a patient chart ended once documentation of tobacco cessation was found, some patients may have relapsed after quitting.

The study site likely could have offered better notice of the presence of the DIGMA. Although flyers and advertisements were available and posted, some tobacco-using patients may not have been aware of the DIGMA. The SFVAHCS could increase awareness of the program if the pharmacy provided a DIGMA flyer with each outpatient tobacco cessation prescription.

A larger, prospective study would be beneficial and might show statistically significant differences in tobacco quit rates. Further studies that address whether the DIGMA helps patients who have quit tobacco to remain tobacco free are needed.

Conclusion

Patients who attended the tobacco cessation DIGMA received personalized care and had a higher tobacco quit rate than did patients receiving standard treatment. However, due to study limitations, these results should be confirmed with future studies.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Sioux Falls VA Health Care System in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Every year in the U.S., more than 435,000 people die of illnesses related to tobacco use.1 The CDC reported that from 2012 to 2013, 21.3% of adults used some form of tobacco daily or on some days.2 Veterans are not excluded from these numbers: A 2005 survey found 22.2% of VA patients were current smokers, and 71.2% of VA patients had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their life.3

Military personnel have a higher propensity to be in situations that increase the risk of tobacco use than the general population does.3,4 These situations include alternating between periods of high stress and boredom, separation from loved ones, perceived camaraderie involved with tobacco use, and the limitation of healthier coping mechanisms.3,4 Stress and boredom have been cited as the top reasons for initiating tobacco use when deployed.3,4 Furthermore, once military personnel return from deployment, they may have difficulty quitting tobacco due to depression, sleeplessness, change in the structure of everyday life, or a second deployment.4

In 2009 Bondurant and Wedge predicted that the VA would spend $30.9 billion in preventable smoking-related expenditures by 2024.3 The negative health effects and the financial impact of tobacco make cessation programs an important investment for the VA.

In 2012, the CDC reported that 70% of veterans want to quit tobacco; therefore, veterans likely would be interested in tobacco cessation programs.4 Reasons veterans noted for quitting included family, changes in the social norm, better overall health, and better ability to breathe.4 Veterans also identified that tobacco cessation programs with convenience, personalization, reduced-cost medications, and peer support would be most helpful.4

According to a 2008 tobacco use and dependence guideline update, the most effective therapy for quitting tobacco is counseling plus pharmacotherapy.1 According to the guideline, the number of counseling sessions combined with pharmacotherapy is strongly related to the likelihood of quitting.1 A number of studies also have shown that telephone counseling is effective for tobacco cessation.5 However, a previous study in veterans found that scheduled face-to-face counseling sessions may be more effective than telephone counseling.6 Dent and colleagues found a statistically significant quit rate at 6 months of 28% in the face-to-face group vs 11.8% in the telephone group.6

After reviewing the guidelines, analyzing the studies, and learning what veterans find most helpful in tobacco cessation programs, the Sioux Falls VA Health Care System (SFVAHCS) in South Dakota took a unique approach to tobacco cessation. In 2012, SFVAHCS implemented a tobacco cessation drop-in group medical appointment (DIGMA) to improve tobacco quit rates. The DIGMA is a 1-hour, educational supportive clinic that allows veterans to drop in during any class anytime, regardless of their tobacco use status. This clinic mostly serves outpatients; however, inpatients also are welcome. Patients are informed of the DIGMA by a health care provider (HCP) or patient information flyers posted throughout SFVAHCS.

The DIGMA takes place once a week in a classroom next to a primary care waiting area, making it easily accessible. During the DIGMA, an HCP, such as a nurse or physician, provides behavioral education. VA materials (Primary Care and Tobacco Cessation Handbook and My Tobacco Cessation Workbook designed by Julianne Himstreet, PharmD, BCPS) are used to guide classes.7,8 These books address barriers to quitting, coping with nicotine withdrawal, planning for quit day, handling tobacco cravings, watching out for triggers, and staying tobacco free.7,8 Clinical pharmacists also are present at the DIGMA for patients who want to start or continue pharmacotherapy. The pharmacists can prescribe tobacco cessation medications and follow up on the success or adverse effects (AEs) of therapy.

The purpose of this study was to examine how a voluntary, drop-in, face-to-face tobacco cessation clinic impacts tobacco quit rates in veterans receiving pharmacotherapy.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed for all study site outpatients started on pharmacotherapy for tobacco cessation between September 1, 2012 and August 31, 2013, as determined by pharmacy dispensing records. Two groups were evaluated in this study: the pharmacotherapy-only (PO) group and the DIGMA group. Pharmacotherapy was most often prescribed by an HCP in the PO group. Other prescribers may have included pharmacists, mental health providers, and hospitalists. The second group was the DIGMA group, which included patients who were on tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy and attended at least 1 DIGMA class within a year of starting pharmacotherapy.

For this study, pharmacotherapy included nicotine gum, nicotine lozenge, nicotine patch, bupropion, varenicline, and any combination of these medications. Patients were excluded if they died, moved, or were lost to follow-up within 1 year of starting pharmacotherapy for a new quit attempt; were not at the beginning of a quit attempt; or were taking bupropion for mood or depression only.

One hundred thirty-six patients attended the DIGMA during the study period, but only 49 patients met the inclusion criteria. Patients also were excluded because they were not at the beginning of a quit attempt, were not receiving pharmacotherapy, or were not seen by an HCP to assess tobacco status after receiving tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy.

A total of 1,807 patients were identified as potential candidates for the PO group. Once the DIGMA patients were identified, an equal number of patients were randomly chosen for the PO group. To ensure that the PO group was random, the patient list was alphabetized, and patients were selected if they met the PO inclusion criteria, starting at the top of the list and moving down until the needed number was met.

The primary endpoint was the tobacco quit rate within 1 year of starting pharmacotherapy for a new quit attempt. Tobacco use status was determined from the patient’s electronic medical record. A subgroup analysis was performed to determine the percentage of patients using each tobacco cessation medication or a combination of medications at the time of the reported quit date.

This study also looked at the number of DIGMA classes attended by patients who quit tobacco and the number of times patients switched pharmacotherapy during the 1-year time frame. A chi-square test was executed to evaluate the primary endpoint, and descriptive statistics were performed for the subgroup analysis. A P value of ≤ .05 was deemed significant.

Results

A total of 98 patients were included with 49 patients in each study arm. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups with an average age of 54 years in both groups (Table). As shown in Figure 1, 40.8% of patients in the DIGMA group quit tobacco compared with 26.5% in the PO group (P = .19).

Discussion

The tobacco quit rate of veterans on pharmacotherapy who attended at least 1 DIGMA class was higher than the quit rate of veterans on pharmacotherapy only. Although the difference between quit rates was not statistically significant, the difference was clinically important. Every time a patient quits tobacco, years of negative health consequences and cost to the health care system may be prevented. Patients who quit tobacco and continue to attend DIGMA classes also can provide support and advice to others who are trying to quit.

The study results also suggest that the tobacco cessation DIGMA provided personalized care to veterans, as demonstrated by patients in the DIGMA group switching pharmacotherapy and using combination therapy more often. Access to pharmacists who can prescribe medications, change therapy, and assist with AEs gave patients the opportunity to determine the most efficacious therapy. Pharmacists also are aware of the pros and cons of the different tobacco cessation medications and are able to help patients pick the best medication to start with or change to.

Patients in the DIGMA group who quit tobacco attended an average of 1.4 classes. Those who attended the DIGMA may have been inherently more motivated to quit tobacco. However, the unique design of the DIGMA may have better equipped patients to quit tobacco after just 1 or 2 classes.

Limitations

Overall, an average attendance of 1.4 classes is a limitation; previous studies have shown that quit rates have a positive correlation with the number of counseling sessions attended.1 Another limitation is the small sample size. In addition, statistical power was not calculated. Tobacco use was not consistently documented in patients’ charts by the HCP and may not have been addressed at every visit. Some patients who quit tobacco may have been missed due to the lack of documentation of tobacco use status. Last, because reviewing a patient chart ended once documentation of tobacco cessation was found, some patients may have relapsed after quitting.

The study site likely could have offered better notice of the presence of the DIGMA. Although flyers and advertisements were available and posted, some tobacco-using patients may not have been aware of the DIGMA. The SFVAHCS could increase awareness of the program if the pharmacy provided a DIGMA flyer with each outpatient tobacco cessation prescription.

A larger, prospective study would be beneficial and might show statistically significant differences in tobacco quit rates. Further studies that address whether the DIGMA helps patients who have quit tobacco to remain tobacco free are needed.

Conclusion

Patients who attended the tobacco cessation DIGMA received personalized care and had a higher tobacco quit rate than did patients receiving standard treatment. However, due to study limitations, these results should be confirmed with future studies.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Sioux Falls VA Health Care System in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical practice guidelines. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Health Resource and Services Administration website. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/buckets/treatingtobacco.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed July 8, 2016.

2. Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco product use among adults--United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):542-547.

3. Bondurant S, Wedge R, eds. Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009.

4. Gierisch JM, Straits-Tröster K, Calhoun PS, Beckham JC, Acheson S, Hamlett-Berry K. Tobacco use among Iraq- and Afghanistan-era veterans: a qualitative study of barriers, facilitators, and treatment p. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E58.

5. Chen T, Kazerooni R, Vannort E, et al. Comparison of an intensive pharmacist-managed telephone clinic with standard of care for tobacco cessation in a veteran population. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(4):512-520.

6. Dent LA, Harris KJ, Noonan CW. Randomized trial assessing the effectiveness of a pharmacist-delivered program for smoking cessation. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(2):194-201.

7. Himstreet J. My Tobacco Cessation Workbook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014.

8. Himstreet J. Primary Care & Tobacco Cessation Handbook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2013.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical practice guidelines. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Health Resource and Services Administration website. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/buckets/treatingtobacco.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed July 8, 2016.

2. Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco product use among adults--United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):542-547.

3. Bondurant S, Wedge R, eds. Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009.

4. Gierisch JM, Straits-Tröster K, Calhoun PS, Beckham JC, Acheson S, Hamlett-Berry K. Tobacco use among Iraq- and Afghanistan-era veterans: a qualitative study of barriers, facilitators, and treatment p. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E58.

5. Chen T, Kazerooni R, Vannort E, et al. Comparison of an intensive pharmacist-managed telephone clinic with standard of care for tobacco cessation in a veteran population. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(4):512-520.

6. Dent LA, Harris KJ, Noonan CW. Randomized trial assessing the effectiveness of a pharmacist-delivered program for smoking cessation. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(2):194-201.

7. Himstreet J. My Tobacco Cessation Workbook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014.

8. Himstreet J. Primary Care & Tobacco Cessation Handbook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2013.