User login

As the prevalence of serious illness among the elderly population has increased, interest in palliative care has grown as an approach to care management that is patient-centered and focused on quality of life. Case management that employs palliative care has the potential to alleviate unnecessary pain and suffering for patients while they concurrently pursue life-prolonging therapy. Palliative care can be provided across the continuum of care, involving multiple health care providers and practitioners.

Home health care, while often used as a postacute care provider, also can provide longitudinal care to elderly patients without a preceding hospitalization. Home health providers often act as central liaisons to coordinate care while patients are at home, particularly chronically ill patients with multiple physician providers, complex medication regimens, and ongoing concerns with independence and safety in the home.

Home health care can play a critical role in providing palliative care and, through innovative programs, can improve access to it. This article provides context and background on the provision of palliative care and explores how home health can work seamlessly in coordination with other health care stakeholders in providing palliative care.

WHAT IS PALLIATIVE CARE?

Palliative care means patient- and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and [facilitating] patient autonomy, access to information, and choice.1

At its core, palliative care is a field of medicine aimed at alleviating the suffering of patients. As a “philosophy of care,” palliative care is appropriate for various sites of care at various stages of disease and all ages of patients. While hospice care is defined by the provision of palliative care for patients at the end of life, not all palliative care is hospice care. Rather, palliative care is an approach to care for any patient diagnosed with a serious illness that leverages expertise from multidisciplinary teams of health professionals and addresses pain and symptoms.

Palliative care addresses suffering by incorporating psychosocial and spiritual care with consideration of patient and family needs, preferences, values, beliefs and cultures. Palliative care can be provided throughout the continuum of care for patients with chronic, serious, and even life-threatening illnesses.1 To a degree, all aspects of health care can potentially address some palliative issues in that health care providers ideally combine a desire to cure the patient with a need to alleviate the patient’s pain and suffering.

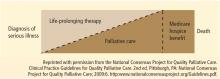

Although the Medicare program recognizes the potential breadth of palliative care, the hospice benefit is relatively narrow. Consistent with the depiction in the Figure,2 the Medicare hospice benefit is limited to care that is focused on “comfort, not on curing an illness”3 (emphasis added). The Medicare hospice benefit is available to Medicare beneficiaries who: (1) are eligible for Medicare Part A; (2) have a doctor and hospice medical director certifying that they are terminally ill and have 6 months or less to live if their illness runs its normal course; (3) sign a statement choosing hospice care instead of other Medicare-covered benefits to treat their terminal illness (although Medicare will still pay for covered benefits for any health problems that are not related to the terminal illness); and (4) get care from a Medicare-certified hospice program.3

There are, however, clear benefits to providing palliative care outside of the Medicare hospice benefit. In particular, patients with serious illnesses may have more than 6 months to live if their illness runs its normal course. Patients who may die within 1 year due to serious illness can benefit from palliative care. Furthermore, some patients would like to continue to pursue curative treatment of their illnesses, but would benefit from a palliative care approach. By providing palliative care in the context of a plan of care with the patient’s physician, the patient and family can comprehensively make decisions and obtain support that enables access to appropriate treatments while allowing enhanced quality of life through symptom management.

WHO CAN PROVIDE PALLIATIVE CARE?

Palliative care can be provided in any care setting that has been accredited or certified to provide care, including those that are upstream from hospice along the continuum of care. Hospitals, nursing homes, and home health agencies can provide palliative care.

The Joint Commission, a nonprofit accrediting organization, currently accredits or certifies more than 17,000 organizations or programs across the care continuum, including hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices. Within the scope of the home care accreditation program, hospices and home health agencies are evaluated by certified field representatives to determine the extent to which their services meet the standards established by The Joint Commission. These standards are developed with input from health care professionals, providers, subject matter experts, consumers, government agencies (including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS]) and employers. They are informed by scientific literature and expert consensus and approved by the board of commissioners.

The Joint Commission also has a certification program for palliative care services provided in hospitals and has certified 21 palliative care programs at various hospitals in the United States.

The Joint Commission’s Advanced Certification Program for Palliative Care recognizes hospital inpatient programs that demonstrate exceptional patient-and family-centered care and optimize quality of life for patients (both adult and pediatric) with serious illness. Certification standards emphasize:

- A formal, organized, palliative care program led by an interdisciplinary team whose members are experts in palliative care

- Leadership endorsement and support of the program’s goals for providing care, treatment and services

- Special focus on patient and family engagement

- Processes that support the coordination of care and communication among all care settings and providers

- The use of evidence-based national guidelines or expert consensus to guide patient care

The certification standards cover program management, provision of care, information management, and performance improvement. The standards are built on the National Consensus Project’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care2 and the National Quality Forum’s National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality.4 Many of the concepts contained in the standards for inpatient palliative care have their origins in hospice care.

In addition to palliative care accreditation programs, certification in palliative care for clinicians is also possible. The American Board of Medical Specialties approved the creation of hospice and palliative medicine as a subspecialty in 2006. The National Board of Certification of Hospice and Palliative Nurses offers specialty certification for all levels of hospice and palliative care nursing. The National Association of Social Workers also offers an advanced certified hospice and palliative social worker (ACHP-SW) certifcation for MSW-level clinicians. These certification programs establish qualifications and standards for the members of a palliative care team.

Subject to federal and state requirements that regulate the way health care is provided, hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices are able to provide palliative care to patients who need such care.5,6

WHAT IS HOME HEALTH’S ROLE IN PROVIDING PALLIATIVE CARE?

Many Medicare-certified home health agencies also operate Medicare-approved hospice programs. Home health agencies have a heightened perspective on patients’ palliative care needs. Because of the limited nature of the Medicare hospice benefit, home health agencies have built palliative care programs to fill unmet patient needs. Home health agencies often provide palliative care to patients who may be ineligible for the hospice benefit or have chosen not to enroll in it. These programs are particularly attractive to patients who would like to pursue curative treatment for their serious illnesses or who are expected to live longer than 6 months.

Home health patients with advancing or serious illness or chronic illness are candidates for a palliative care service. For these patients, the burden of their illness continues to grow as distressing symptoms begin to more regularly impact their quality of life. As they continue curative treatment of their illness, they would benefit from palliative care services that provide greater relief of their symptoms and support advanced care planning. Palliative care interventions become an integrated part of the care plan for these patients. Home health agencies serving patients with chronic or advancing illnesses will see care benefits from incorporating palliative care into their team’s skill set.

Two innovative examples of home health–based programs that include a palliative care component have been reported in peer-reviewed literature to date: Kaiser Permanente’s In-Home Palliative Care program and Sutter Health’s Advanced Illness Management (AIM) program.7–10

Kaiser Permanente’s In-Home Palliative Care Program

Kaiser Permanente (KP) established the TriCentral Palliative Care Program in 1998 to achieve balance for seriously ill patients facing the end of life who were caught between “the extremes of too little care and too much.”11 KP began the program after discovering that patients were underusing their existing hospice program. The TriCentral Palliative Care program is an outpatient service, housed in the KP home health department and modeled after the KP hospice program with three key modifications designed to encourage timely referrals to the program:

- Physicians are asked to refer a patient if they “would not be surprised if this patient died in the next year.” Palliative care patients with a prognosis of 12 months or less to live are accepted into the program.

- Improved pain control and symptom management are emphasized, but patients do not need to forgo curative care as they do in hospice programs.

- Patients are assigned a palliative care physician who coordinates care from a variety of health care providers, preventing fragmentation.

The program has five core components that are geared toward enhanced quality of care and patient quality of life. These core components are:

- An interdisciplinary team approach, focused on patient and family, with care provided by a core team consisting of a physician, nurse, and social worker, all with expertise in pain control, other symptom management, and psychosocial intervention

- Home visits by all team members, including physicians, to provide medical care, support, and education as needed by patients and their caregivers

- Ongoing care management to fill gaps in care and ensure that the patient’s medical, social, and spiritual needs are being met

- Telephone support via a toll-free number and after-hours home visits available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as needed by the patient

- Advanced-care planning that empowers patients and their families to make informed decisions and choices about end-of-life care11

Assessments of the program’s results in a randomized controlled trial8 and a comparative study9 showed that patient satisfaction increased; patients were more likely to die at home in accordance with their wishes; and emergency department (ED) visits, inpatient admissions, and costs were reduced (Table 1).

Sutter Health AIM Program

Sutter Health in northern California, in collaboration with its home care and hospice affiliate, Sutter Care at Home, initiated a home health–based program, Advanced Illness Management (AIM), in 2000 in response to the growing population of patients with advanced illness who needed enhanced care planning and symptom management. This program served patients who met the Medicare eligibility criteria for home health, had a prognosis of 1 year or less, and were continuing to seek treatment or cure for their illness. These patients frequently lacked awareness of their health status, particularly as it related to choices and decisions connected to the progression and management of their conditions. They also were frequently receiving uncoordinated care through various health channels, resulting in substandard symptom management. As a result, patients tended to experience more acute episodes that required frequent use of “unwanted and inappropriate care at the end of life, and they, their families, and their providers were dissatisfied.”12

As the AIM program matured, it incorporated a broader care management model, including principles of patient/caregiver engagement and goal setting, self-management techniques, ongoing advanced care planning, symptom management, and other evidence-based practices related to care transitions and care management. The program connects with the patient’s network of care providers and coordinates the exchange of realtime information about the current status of care plans and medication, as well as the patient’s defined goals. This more comprehensive model of care for persons with advanced illness has achieved improved adherence to patient wishes and goals, reductions in unnecessary hospital and ED utilization, and higher patient/caregiver and provider satisfaction than usual care.

Today, AIM is not primarily a palliative care program. Rather, it provides a comprehensive approach to care management that moves the focus of care for advanced illness out of the hospital and into the home/community setting. AIM achieves this through integrating the patient’s “health system.”

This integration occurs through formation of an interdisciplinary team comprised of the home care team, representative clinicians connected to the hospital, and providers of care for the patient. This expanded team, then, becomes the AIM care management team that is trained on the principles of AIM and its interventions. With this enhanced level of care coordination and unified focus on supporting the patient’s personal health goals, the AIM program serves as a “health system integrator” for the vulnerable and costly population of people with advanced chronic illness.

Inpatient palliative care is a separate and distinct systemwide priority at Sutter Health and, because of this, AIM collaborates closely with the inpatient palliative care teams to ensure that patients experience a seamless transition from hospital to home. There, AIM staff work with patients and families over time to clarify and document their personal values and goals, then use these to develop and drive the care plan. Armed with clearer appreciation of the natural progression of illness, both clinically and practically, coupled with improved understanding of available options for care, most choose to stay in the safety and comfort of their homes and out of the hospital. These avoided hospitalizations are the primary source of AIM’s considerable cost savings.

Patients eligible for AIM are those with clinical, functional, or nutritional decline; with multiple hospitalizations, ED visits, or both within the past 12 months; and who are clinically eligible for hospice but have chosen to continue treatment or have not otherwise made the decision to use a hospice model of care. Once the patient is enrolled, the AIM team works with the patient, the family, and the physician on a preference-driven plan of care. That plan is shared with all providers supporting the patient and is regularly updated to reflect changes in the patient’s evolving choices as illness advances. This tracking of goals and preferences over time as illness progresses has been a critical factor in improving outcomes, especially those related to adherence or honoring a patient’s personal goals.

The AIM program started as a symptom management and care planning intervention for Medicare-eligible home health patients. The program has evolved over time into a pivotal fulcrum by which to engage or create an interdisciplinary focus and skill set across sites and providers of care in an effort to improve the overall outcomes for patients with advancing illness. In 2009, the AIM program began geographically expanding its home health–based AIM teams across 12 counties surrounding the San Francisco Bay area and the greater Sacramento region in northern California. The program now coordinates care with more than 17 hospitals and all of the large Sutter-affiliated medical groups, and it serves approximately 800 patients per day.

The AIM program has yielded significant results in terms of both quality of care and cost savings. Preliminary data on more than 300 AIM patients surveyed from November 2009 through September 2010 showed significant reductions in unnecessary hospitalizations and inpatient direct care costs (Table 2).12 Survey data also showed significant improvements in patient, family, and physician satisfaction when late-stage patients were served through AIM rather than through home care by itself.12

The Sutter Health AIM program recently received a Health Care Innovation Award from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) because of the program’s ability to “improve care and patient quality of life, increase physician, caregiver, and patient satisfaction, and reduce Medicare costs associated with avoidable hospital stays, ED visits, and days spent in intensive care units and skilled nursing facilities.”13 The $13 million CMMI grant will help expand AIM to the entire Sutter Health system. It is estimated that the program will save $29,388,894 over 3 years.13

CONCLUSION: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE US HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

The basic objective of AIM and programs like it is to move the focus of care for people with advanced illness out of the hospital and into home and community. This fulfills the Triple Aim vision set forth in 2008 by former CMS Administrator Don Berwick14:

- Improving health by reducing inpatient care that does not achieve person-centered goals or reduce overall mortality

- Improving care by basing it on the values and goals of people dealing with serious chronic illness

- Reducing costs by preventing unwanted hospital care

Sutter Health, a system that is on its way to becoming fully clinically integrated, was a logical choice for launching AIM because its hospitals are forming relationships with physician groups and home care providers. This integration process is supported nationally by CMS and CMMI, which are promoting new models of care and reimbursement such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments.

Nonintegrated hospitals and other provider groups can move in this same direction. AIM establishes key care coordination roles in each setting of care such as in hospitals and physician offices, as well as in the home care–based team and providers. The AIM care model emphasizes close coordination of clinical activities and communications, and integrates these with hospital and medical group operations. These provider groups can move strategically toward becoming “virtual ACOs” by coordinating care for people with advanced illness, who comprise the most vulnerable and costly segment of the US population and increasingly impact Medicare expenditures.

Changes in federal policy will be needed to facilitate national implementation of AIM-like programs. If ACOs and bundled payments were to be implemented overnight, the person-centered, cost-saving advantages of AIM would be obvious. However, until shared risk/shared savings models replace fee-for-service reimbursement, new payment policies will be needed on an interim basis to cover the costs of currently nonreimbursed care management services. This could be arranged through a per-enrollee-per-month payment or shared savings models tied to specific quality and utilization outcomes.

Simplification of regulatory requirements to better serve persons with advancing illness and to reduce the burden on providers operating such programs would be valuable. The pattern or progression of advancing chronic illness requires ongoing coordination in order to maintain a higher quality of life and symptom management. Current regulations and requirements foster an episodic focus in the home, as well in the hospital and physician’s office, which is not in alignment with the experience of persons living with advancing illness.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid program: conditions of participation. Federal Register 2008; 73:32088–32219.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. National Consensus Project Web site. http:www.nationalconsensusproject.org. Published 2009. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- Medicare hospice benefits. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/02154.pdf. Revised August 2012. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- A national framework and preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality. A consensus report. National Quality Forum Web site. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2006/12/A_National_Framework_and_Preferred_Practices_for_Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Quality.aspx. Published 2006. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- Michal MH, Pekarske MSL. Palliative care checklist: selected regulatory and risk management considerations. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Web site. http://www.nhpco.org/fles/public/palliativecare/pcchecklist.pdf. Published April 17, 2006. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Raffa CA. Palliative care: the legal and regulatory requirements. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Web site. http://www.nhpco.org/files/public/palliativecare/legal_regulatorypart2.pdf. Published December 22, 2003. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- In-home palliative care allows more patients to die at home, leading to higher satisfaction and lower acute care utilization and costs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Care Innovations Exchange Web site. http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=2366. Published March 2, 2009. Updated November 07, 2012. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:993–1000.

- Enguidanos SM, Cherin D, Brumley R. Home-based palliative care study: site of death, and costs of medical care for patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2005; 1:37–56.

- Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med 2003; 6:715–724.

- Brumley RD, Hillary K. The TriCentral Palliative Care Program Toolkit. 1st ed. MyWhatever Web site. http://www.mywhatever.com/cifwriter/content/22/fles/sorostoolkitfnal120902.doc. Published 2002. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Meyer H. Innovation profile: changing the conversation in California about care near the end of life. Health Aff 2011; 30:390–393.

- Health Care Innovation Awards. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation Web site. http://innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/Innovation-Awards/california.html. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Berwick DJ, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff 2008; 27:759–769.

As the prevalence of serious illness among the elderly population has increased, interest in palliative care has grown as an approach to care management that is patient-centered and focused on quality of life. Case management that employs palliative care has the potential to alleviate unnecessary pain and suffering for patients while they concurrently pursue life-prolonging therapy. Palliative care can be provided across the continuum of care, involving multiple health care providers and practitioners.

Home health care, while often used as a postacute care provider, also can provide longitudinal care to elderly patients without a preceding hospitalization. Home health providers often act as central liaisons to coordinate care while patients are at home, particularly chronically ill patients with multiple physician providers, complex medication regimens, and ongoing concerns with independence and safety in the home.

Home health care can play a critical role in providing palliative care and, through innovative programs, can improve access to it. This article provides context and background on the provision of palliative care and explores how home health can work seamlessly in coordination with other health care stakeholders in providing palliative care.

WHAT IS PALLIATIVE CARE?

Palliative care means patient- and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and [facilitating] patient autonomy, access to information, and choice.1

At its core, palliative care is a field of medicine aimed at alleviating the suffering of patients. As a “philosophy of care,” palliative care is appropriate for various sites of care at various stages of disease and all ages of patients. While hospice care is defined by the provision of palliative care for patients at the end of life, not all palliative care is hospice care. Rather, palliative care is an approach to care for any patient diagnosed with a serious illness that leverages expertise from multidisciplinary teams of health professionals and addresses pain and symptoms.

Palliative care addresses suffering by incorporating psychosocial and spiritual care with consideration of patient and family needs, preferences, values, beliefs and cultures. Palliative care can be provided throughout the continuum of care for patients with chronic, serious, and even life-threatening illnesses.1 To a degree, all aspects of health care can potentially address some palliative issues in that health care providers ideally combine a desire to cure the patient with a need to alleviate the patient’s pain and suffering.

Although the Medicare program recognizes the potential breadth of palliative care, the hospice benefit is relatively narrow. Consistent with the depiction in the Figure,2 the Medicare hospice benefit is limited to care that is focused on “comfort, not on curing an illness”3 (emphasis added). The Medicare hospice benefit is available to Medicare beneficiaries who: (1) are eligible for Medicare Part A; (2) have a doctor and hospice medical director certifying that they are terminally ill and have 6 months or less to live if their illness runs its normal course; (3) sign a statement choosing hospice care instead of other Medicare-covered benefits to treat their terminal illness (although Medicare will still pay for covered benefits for any health problems that are not related to the terminal illness); and (4) get care from a Medicare-certified hospice program.3

There are, however, clear benefits to providing palliative care outside of the Medicare hospice benefit. In particular, patients with serious illnesses may have more than 6 months to live if their illness runs its normal course. Patients who may die within 1 year due to serious illness can benefit from palliative care. Furthermore, some patients would like to continue to pursue curative treatment of their illnesses, but would benefit from a palliative care approach. By providing palliative care in the context of a plan of care with the patient’s physician, the patient and family can comprehensively make decisions and obtain support that enables access to appropriate treatments while allowing enhanced quality of life through symptom management.

WHO CAN PROVIDE PALLIATIVE CARE?

Palliative care can be provided in any care setting that has been accredited or certified to provide care, including those that are upstream from hospice along the continuum of care. Hospitals, nursing homes, and home health agencies can provide palliative care.

The Joint Commission, a nonprofit accrediting organization, currently accredits or certifies more than 17,000 organizations or programs across the care continuum, including hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices. Within the scope of the home care accreditation program, hospices and home health agencies are evaluated by certified field representatives to determine the extent to which their services meet the standards established by The Joint Commission. These standards are developed with input from health care professionals, providers, subject matter experts, consumers, government agencies (including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS]) and employers. They are informed by scientific literature and expert consensus and approved by the board of commissioners.

The Joint Commission also has a certification program for palliative care services provided in hospitals and has certified 21 palliative care programs at various hospitals in the United States.

The Joint Commission’s Advanced Certification Program for Palliative Care recognizes hospital inpatient programs that demonstrate exceptional patient-and family-centered care and optimize quality of life for patients (both adult and pediatric) with serious illness. Certification standards emphasize:

- A formal, organized, palliative care program led by an interdisciplinary team whose members are experts in palliative care

- Leadership endorsement and support of the program’s goals for providing care, treatment and services

- Special focus on patient and family engagement

- Processes that support the coordination of care and communication among all care settings and providers

- The use of evidence-based national guidelines or expert consensus to guide patient care

The certification standards cover program management, provision of care, information management, and performance improvement. The standards are built on the National Consensus Project’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care2 and the National Quality Forum’s National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality.4 Many of the concepts contained in the standards for inpatient palliative care have their origins in hospice care.

In addition to palliative care accreditation programs, certification in palliative care for clinicians is also possible. The American Board of Medical Specialties approved the creation of hospice and palliative medicine as a subspecialty in 2006. The National Board of Certification of Hospice and Palliative Nurses offers specialty certification for all levels of hospice and palliative care nursing. The National Association of Social Workers also offers an advanced certified hospice and palliative social worker (ACHP-SW) certifcation for MSW-level clinicians. These certification programs establish qualifications and standards for the members of a palliative care team.

Subject to federal and state requirements that regulate the way health care is provided, hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices are able to provide palliative care to patients who need such care.5,6

WHAT IS HOME HEALTH’S ROLE IN PROVIDING PALLIATIVE CARE?

Many Medicare-certified home health agencies also operate Medicare-approved hospice programs. Home health agencies have a heightened perspective on patients’ palliative care needs. Because of the limited nature of the Medicare hospice benefit, home health agencies have built palliative care programs to fill unmet patient needs. Home health agencies often provide palliative care to patients who may be ineligible for the hospice benefit or have chosen not to enroll in it. These programs are particularly attractive to patients who would like to pursue curative treatment for their serious illnesses or who are expected to live longer than 6 months.

Home health patients with advancing or serious illness or chronic illness are candidates for a palliative care service. For these patients, the burden of their illness continues to grow as distressing symptoms begin to more regularly impact their quality of life. As they continue curative treatment of their illness, they would benefit from palliative care services that provide greater relief of their symptoms and support advanced care planning. Palliative care interventions become an integrated part of the care plan for these patients. Home health agencies serving patients with chronic or advancing illnesses will see care benefits from incorporating palliative care into their team’s skill set.

Two innovative examples of home health–based programs that include a palliative care component have been reported in peer-reviewed literature to date: Kaiser Permanente’s In-Home Palliative Care program and Sutter Health’s Advanced Illness Management (AIM) program.7–10

Kaiser Permanente’s In-Home Palliative Care Program

Kaiser Permanente (KP) established the TriCentral Palliative Care Program in 1998 to achieve balance for seriously ill patients facing the end of life who were caught between “the extremes of too little care and too much.”11 KP began the program after discovering that patients were underusing their existing hospice program. The TriCentral Palliative Care program is an outpatient service, housed in the KP home health department and modeled after the KP hospice program with three key modifications designed to encourage timely referrals to the program:

- Physicians are asked to refer a patient if they “would not be surprised if this patient died in the next year.” Palliative care patients with a prognosis of 12 months or less to live are accepted into the program.

- Improved pain control and symptom management are emphasized, but patients do not need to forgo curative care as they do in hospice programs.

- Patients are assigned a palliative care physician who coordinates care from a variety of health care providers, preventing fragmentation.

The program has five core components that are geared toward enhanced quality of care and patient quality of life. These core components are:

- An interdisciplinary team approach, focused on patient and family, with care provided by a core team consisting of a physician, nurse, and social worker, all with expertise in pain control, other symptom management, and psychosocial intervention

- Home visits by all team members, including physicians, to provide medical care, support, and education as needed by patients and their caregivers

- Ongoing care management to fill gaps in care and ensure that the patient’s medical, social, and spiritual needs are being met

- Telephone support via a toll-free number and after-hours home visits available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as needed by the patient

- Advanced-care planning that empowers patients and their families to make informed decisions and choices about end-of-life care11

Assessments of the program’s results in a randomized controlled trial8 and a comparative study9 showed that patient satisfaction increased; patients were more likely to die at home in accordance with their wishes; and emergency department (ED) visits, inpatient admissions, and costs were reduced (Table 1).

Sutter Health AIM Program

Sutter Health in northern California, in collaboration with its home care and hospice affiliate, Sutter Care at Home, initiated a home health–based program, Advanced Illness Management (AIM), in 2000 in response to the growing population of patients with advanced illness who needed enhanced care planning and symptom management. This program served patients who met the Medicare eligibility criteria for home health, had a prognosis of 1 year or less, and were continuing to seek treatment or cure for their illness. These patients frequently lacked awareness of their health status, particularly as it related to choices and decisions connected to the progression and management of their conditions. They also were frequently receiving uncoordinated care through various health channels, resulting in substandard symptom management. As a result, patients tended to experience more acute episodes that required frequent use of “unwanted and inappropriate care at the end of life, and they, their families, and their providers were dissatisfied.”12

As the AIM program matured, it incorporated a broader care management model, including principles of patient/caregiver engagement and goal setting, self-management techniques, ongoing advanced care planning, symptom management, and other evidence-based practices related to care transitions and care management. The program connects with the patient’s network of care providers and coordinates the exchange of realtime information about the current status of care plans and medication, as well as the patient’s defined goals. This more comprehensive model of care for persons with advanced illness has achieved improved adherence to patient wishes and goals, reductions in unnecessary hospital and ED utilization, and higher patient/caregiver and provider satisfaction than usual care.

Today, AIM is not primarily a palliative care program. Rather, it provides a comprehensive approach to care management that moves the focus of care for advanced illness out of the hospital and into the home/community setting. AIM achieves this through integrating the patient’s “health system.”

This integration occurs through formation of an interdisciplinary team comprised of the home care team, representative clinicians connected to the hospital, and providers of care for the patient. This expanded team, then, becomes the AIM care management team that is trained on the principles of AIM and its interventions. With this enhanced level of care coordination and unified focus on supporting the patient’s personal health goals, the AIM program serves as a “health system integrator” for the vulnerable and costly population of people with advanced chronic illness.

Inpatient palliative care is a separate and distinct systemwide priority at Sutter Health and, because of this, AIM collaborates closely with the inpatient palliative care teams to ensure that patients experience a seamless transition from hospital to home. There, AIM staff work with patients and families over time to clarify and document their personal values and goals, then use these to develop and drive the care plan. Armed with clearer appreciation of the natural progression of illness, both clinically and practically, coupled with improved understanding of available options for care, most choose to stay in the safety and comfort of their homes and out of the hospital. These avoided hospitalizations are the primary source of AIM’s considerable cost savings.

Patients eligible for AIM are those with clinical, functional, or nutritional decline; with multiple hospitalizations, ED visits, or both within the past 12 months; and who are clinically eligible for hospice but have chosen to continue treatment or have not otherwise made the decision to use a hospice model of care. Once the patient is enrolled, the AIM team works with the patient, the family, and the physician on a preference-driven plan of care. That plan is shared with all providers supporting the patient and is regularly updated to reflect changes in the patient’s evolving choices as illness advances. This tracking of goals and preferences over time as illness progresses has been a critical factor in improving outcomes, especially those related to adherence or honoring a patient’s personal goals.

The AIM program started as a symptom management and care planning intervention for Medicare-eligible home health patients. The program has evolved over time into a pivotal fulcrum by which to engage or create an interdisciplinary focus and skill set across sites and providers of care in an effort to improve the overall outcomes for patients with advancing illness. In 2009, the AIM program began geographically expanding its home health–based AIM teams across 12 counties surrounding the San Francisco Bay area and the greater Sacramento region in northern California. The program now coordinates care with more than 17 hospitals and all of the large Sutter-affiliated medical groups, and it serves approximately 800 patients per day.

The AIM program has yielded significant results in terms of both quality of care and cost savings. Preliminary data on more than 300 AIM patients surveyed from November 2009 through September 2010 showed significant reductions in unnecessary hospitalizations and inpatient direct care costs (Table 2).12 Survey data also showed significant improvements in patient, family, and physician satisfaction when late-stage patients were served through AIM rather than through home care by itself.12

The Sutter Health AIM program recently received a Health Care Innovation Award from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) because of the program’s ability to “improve care and patient quality of life, increase physician, caregiver, and patient satisfaction, and reduce Medicare costs associated with avoidable hospital stays, ED visits, and days spent in intensive care units and skilled nursing facilities.”13 The $13 million CMMI grant will help expand AIM to the entire Sutter Health system. It is estimated that the program will save $29,388,894 over 3 years.13

CONCLUSION: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE US HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

The basic objective of AIM and programs like it is to move the focus of care for people with advanced illness out of the hospital and into home and community. This fulfills the Triple Aim vision set forth in 2008 by former CMS Administrator Don Berwick14:

- Improving health by reducing inpatient care that does not achieve person-centered goals or reduce overall mortality

- Improving care by basing it on the values and goals of people dealing with serious chronic illness

- Reducing costs by preventing unwanted hospital care

Sutter Health, a system that is on its way to becoming fully clinically integrated, was a logical choice for launching AIM because its hospitals are forming relationships with physician groups and home care providers. This integration process is supported nationally by CMS and CMMI, which are promoting new models of care and reimbursement such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments.

Nonintegrated hospitals and other provider groups can move in this same direction. AIM establishes key care coordination roles in each setting of care such as in hospitals and physician offices, as well as in the home care–based team and providers. The AIM care model emphasizes close coordination of clinical activities and communications, and integrates these with hospital and medical group operations. These provider groups can move strategically toward becoming “virtual ACOs” by coordinating care for people with advanced illness, who comprise the most vulnerable and costly segment of the US population and increasingly impact Medicare expenditures.

Changes in federal policy will be needed to facilitate national implementation of AIM-like programs. If ACOs and bundled payments were to be implemented overnight, the person-centered, cost-saving advantages of AIM would be obvious. However, until shared risk/shared savings models replace fee-for-service reimbursement, new payment policies will be needed on an interim basis to cover the costs of currently nonreimbursed care management services. This could be arranged through a per-enrollee-per-month payment or shared savings models tied to specific quality and utilization outcomes.

Simplification of regulatory requirements to better serve persons with advancing illness and to reduce the burden on providers operating such programs would be valuable. The pattern or progression of advancing chronic illness requires ongoing coordination in order to maintain a higher quality of life and symptom management. Current regulations and requirements foster an episodic focus in the home, as well in the hospital and physician’s office, which is not in alignment with the experience of persons living with advancing illness.

As the prevalence of serious illness among the elderly population has increased, interest in palliative care has grown as an approach to care management that is patient-centered and focused on quality of life. Case management that employs palliative care has the potential to alleviate unnecessary pain and suffering for patients while they concurrently pursue life-prolonging therapy. Palliative care can be provided across the continuum of care, involving multiple health care providers and practitioners.

Home health care, while often used as a postacute care provider, also can provide longitudinal care to elderly patients without a preceding hospitalization. Home health providers often act as central liaisons to coordinate care while patients are at home, particularly chronically ill patients with multiple physician providers, complex medication regimens, and ongoing concerns with independence and safety in the home.

Home health care can play a critical role in providing palliative care and, through innovative programs, can improve access to it. This article provides context and background on the provision of palliative care and explores how home health can work seamlessly in coordination with other health care stakeholders in providing palliative care.

WHAT IS PALLIATIVE CARE?

Palliative care means patient- and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and [facilitating] patient autonomy, access to information, and choice.1

At its core, palliative care is a field of medicine aimed at alleviating the suffering of patients. As a “philosophy of care,” palliative care is appropriate for various sites of care at various stages of disease and all ages of patients. While hospice care is defined by the provision of palliative care for patients at the end of life, not all palliative care is hospice care. Rather, palliative care is an approach to care for any patient diagnosed with a serious illness that leverages expertise from multidisciplinary teams of health professionals and addresses pain and symptoms.

Palliative care addresses suffering by incorporating psychosocial and spiritual care with consideration of patient and family needs, preferences, values, beliefs and cultures. Palliative care can be provided throughout the continuum of care for patients with chronic, serious, and even life-threatening illnesses.1 To a degree, all aspects of health care can potentially address some palliative issues in that health care providers ideally combine a desire to cure the patient with a need to alleviate the patient’s pain and suffering.

Although the Medicare program recognizes the potential breadth of palliative care, the hospice benefit is relatively narrow. Consistent with the depiction in the Figure,2 the Medicare hospice benefit is limited to care that is focused on “comfort, not on curing an illness”3 (emphasis added). The Medicare hospice benefit is available to Medicare beneficiaries who: (1) are eligible for Medicare Part A; (2) have a doctor and hospice medical director certifying that they are terminally ill and have 6 months or less to live if their illness runs its normal course; (3) sign a statement choosing hospice care instead of other Medicare-covered benefits to treat their terminal illness (although Medicare will still pay for covered benefits for any health problems that are not related to the terminal illness); and (4) get care from a Medicare-certified hospice program.3

There are, however, clear benefits to providing palliative care outside of the Medicare hospice benefit. In particular, patients with serious illnesses may have more than 6 months to live if their illness runs its normal course. Patients who may die within 1 year due to serious illness can benefit from palliative care. Furthermore, some patients would like to continue to pursue curative treatment of their illnesses, but would benefit from a palliative care approach. By providing palliative care in the context of a plan of care with the patient’s physician, the patient and family can comprehensively make decisions and obtain support that enables access to appropriate treatments while allowing enhanced quality of life through symptom management.

WHO CAN PROVIDE PALLIATIVE CARE?

Palliative care can be provided in any care setting that has been accredited or certified to provide care, including those that are upstream from hospice along the continuum of care. Hospitals, nursing homes, and home health agencies can provide palliative care.

The Joint Commission, a nonprofit accrediting organization, currently accredits or certifies more than 17,000 organizations or programs across the care continuum, including hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices. Within the scope of the home care accreditation program, hospices and home health agencies are evaluated by certified field representatives to determine the extent to which their services meet the standards established by The Joint Commission. These standards are developed with input from health care professionals, providers, subject matter experts, consumers, government agencies (including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS]) and employers. They are informed by scientific literature and expert consensus and approved by the board of commissioners.

The Joint Commission also has a certification program for palliative care services provided in hospitals and has certified 21 palliative care programs at various hospitals in the United States.

The Joint Commission’s Advanced Certification Program for Palliative Care recognizes hospital inpatient programs that demonstrate exceptional patient-and family-centered care and optimize quality of life for patients (both adult and pediatric) with serious illness. Certification standards emphasize:

- A formal, organized, palliative care program led by an interdisciplinary team whose members are experts in palliative care

- Leadership endorsement and support of the program’s goals for providing care, treatment and services

- Special focus on patient and family engagement

- Processes that support the coordination of care and communication among all care settings and providers

- The use of evidence-based national guidelines or expert consensus to guide patient care

The certification standards cover program management, provision of care, information management, and performance improvement. The standards are built on the National Consensus Project’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care2 and the National Quality Forum’s National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality.4 Many of the concepts contained in the standards for inpatient palliative care have their origins in hospice care.

In addition to palliative care accreditation programs, certification in palliative care for clinicians is also possible. The American Board of Medical Specialties approved the creation of hospice and palliative medicine as a subspecialty in 2006. The National Board of Certification of Hospice and Palliative Nurses offers specialty certification for all levels of hospice and palliative care nursing. The National Association of Social Workers also offers an advanced certified hospice and palliative social worker (ACHP-SW) certifcation for MSW-level clinicians. These certification programs establish qualifications and standards for the members of a palliative care team.

Subject to federal and state requirements that regulate the way health care is provided, hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices are able to provide palliative care to patients who need such care.5,6

WHAT IS HOME HEALTH’S ROLE IN PROVIDING PALLIATIVE CARE?

Many Medicare-certified home health agencies also operate Medicare-approved hospice programs. Home health agencies have a heightened perspective on patients’ palliative care needs. Because of the limited nature of the Medicare hospice benefit, home health agencies have built palliative care programs to fill unmet patient needs. Home health agencies often provide palliative care to patients who may be ineligible for the hospice benefit or have chosen not to enroll in it. These programs are particularly attractive to patients who would like to pursue curative treatment for their serious illnesses or who are expected to live longer than 6 months.

Home health patients with advancing or serious illness or chronic illness are candidates for a palliative care service. For these patients, the burden of their illness continues to grow as distressing symptoms begin to more regularly impact their quality of life. As they continue curative treatment of their illness, they would benefit from palliative care services that provide greater relief of their symptoms and support advanced care planning. Palliative care interventions become an integrated part of the care plan for these patients. Home health agencies serving patients with chronic or advancing illnesses will see care benefits from incorporating palliative care into their team’s skill set.

Two innovative examples of home health–based programs that include a palliative care component have been reported in peer-reviewed literature to date: Kaiser Permanente’s In-Home Palliative Care program and Sutter Health’s Advanced Illness Management (AIM) program.7–10

Kaiser Permanente’s In-Home Palliative Care Program

Kaiser Permanente (KP) established the TriCentral Palliative Care Program in 1998 to achieve balance for seriously ill patients facing the end of life who were caught between “the extremes of too little care and too much.”11 KP began the program after discovering that patients were underusing their existing hospice program. The TriCentral Palliative Care program is an outpatient service, housed in the KP home health department and modeled after the KP hospice program with three key modifications designed to encourage timely referrals to the program:

- Physicians are asked to refer a patient if they “would not be surprised if this patient died in the next year.” Palliative care patients with a prognosis of 12 months or less to live are accepted into the program.

- Improved pain control and symptom management are emphasized, but patients do not need to forgo curative care as they do in hospice programs.

- Patients are assigned a palliative care physician who coordinates care from a variety of health care providers, preventing fragmentation.

The program has five core components that are geared toward enhanced quality of care and patient quality of life. These core components are:

- An interdisciplinary team approach, focused on patient and family, with care provided by a core team consisting of a physician, nurse, and social worker, all with expertise in pain control, other symptom management, and psychosocial intervention

- Home visits by all team members, including physicians, to provide medical care, support, and education as needed by patients and their caregivers

- Ongoing care management to fill gaps in care and ensure that the patient’s medical, social, and spiritual needs are being met

- Telephone support via a toll-free number and after-hours home visits available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as needed by the patient

- Advanced-care planning that empowers patients and their families to make informed decisions and choices about end-of-life care11

Assessments of the program’s results in a randomized controlled trial8 and a comparative study9 showed that patient satisfaction increased; patients were more likely to die at home in accordance with their wishes; and emergency department (ED) visits, inpatient admissions, and costs were reduced (Table 1).

Sutter Health AIM Program

Sutter Health in northern California, in collaboration with its home care and hospice affiliate, Sutter Care at Home, initiated a home health–based program, Advanced Illness Management (AIM), in 2000 in response to the growing population of patients with advanced illness who needed enhanced care planning and symptom management. This program served patients who met the Medicare eligibility criteria for home health, had a prognosis of 1 year or less, and were continuing to seek treatment or cure for their illness. These patients frequently lacked awareness of their health status, particularly as it related to choices and decisions connected to the progression and management of their conditions. They also were frequently receiving uncoordinated care through various health channels, resulting in substandard symptom management. As a result, patients tended to experience more acute episodes that required frequent use of “unwanted and inappropriate care at the end of life, and they, their families, and their providers were dissatisfied.”12

As the AIM program matured, it incorporated a broader care management model, including principles of patient/caregiver engagement and goal setting, self-management techniques, ongoing advanced care planning, symptom management, and other evidence-based practices related to care transitions and care management. The program connects with the patient’s network of care providers and coordinates the exchange of realtime information about the current status of care plans and medication, as well as the patient’s defined goals. This more comprehensive model of care for persons with advanced illness has achieved improved adherence to patient wishes and goals, reductions in unnecessary hospital and ED utilization, and higher patient/caregiver and provider satisfaction than usual care.

Today, AIM is not primarily a palliative care program. Rather, it provides a comprehensive approach to care management that moves the focus of care for advanced illness out of the hospital and into the home/community setting. AIM achieves this through integrating the patient’s “health system.”

This integration occurs through formation of an interdisciplinary team comprised of the home care team, representative clinicians connected to the hospital, and providers of care for the patient. This expanded team, then, becomes the AIM care management team that is trained on the principles of AIM and its interventions. With this enhanced level of care coordination and unified focus on supporting the patient’s personal health goals, the AIM program serves as a “health system integrator” for the vulnerable and costly population of people with advanced chronic illness.

Inpatient palliative care is a separate and distinct systemwide priority at Sutter Health and, because of this, AIM collaborates closely with the inpatient palliative care teams to ensure that patients experience a seamless transition from hospital to home. There, AIM staff work with patients and families over time to clarify and document their personal values and goals, then use these to develop and drive the care plan. Armed with clearer appreciation of the natural progression of illness, both clinically and practically, coupled with improved understanding of available options for care, most choose to stay in the safety and comfort of their homes and out of the hospital. These avoided hospitalizations are the primary source of AIM’s considerable cost savings.

Patients eligible for AIM are those with clinical, functional, or nutritional decline; with multiple hospitalizations, ED visits, or both within the past 12 months; and who are clinically eligible for hospice but have chosen to continue treatment or have not otherwise made the decision to use a hospice model of care. Once the patient is enrolled, the AIM team works with the patient, the family, and the physician on a preference-driven plan of care. That plan is shared with all providers supporting the patient and is regularly updated to reflect changes in the patient’s evolving choices as illness advances. This tracking of goals and preferences over time as illness progresses has been a critical factor in improving outcomes, especially those related to adherence or honoring a patient’s personal goals.

The AIM program started as a symptom management and care planning intervention for Medicare-eligible home health patients. The program has evolved over time into a pivotal fulcrum by which to engage or create an interdisciplinary focus and skill set across sites and providers of care in an effort to improve the overall outcomes for patients with advancing illness. In 2009, the AIM program began geographically expanding its home health–based AIM teams across 12 counties surrounding the San Francisco Bay area and the greater Sacramento region in northern California. The program now coordinates care with more than 17 hospitals and all of the large Sutter-affiliated medical groups, and it serves approximately 800 patients per day.

The AIM program has yielded significant results in terms of both quality of care and cost savings. Preliminary data on more than 300 AIM patients surveyed from November 2009 through September 2010 showed significant reductions in unnecessary hospitalizations and inpatient direct care costs (Table 2).12 Survey data also showed significant improvements in patient, family, and physician satisfaction when late-stage patients were served through AIM rather than through home care by itself.12

The Sutter Health AIM program recently received a Health Care Innovation Award from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) because of the program’s ability to “improve care and patient quality of life, increase physician, caregiver, and patient satisfaction, and reduce Medicare costs associated with avoidable hospital stays, ED visits, and days spent in intensive care units and skilled nursing facilities.”13 The $13 million CMMI grant will help expand AIM to the entire Sutter Health system. It is estimated that the program will save $29,388,894 over 3 years.13

CONCLUSION: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE US HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

The basic objective of AIM and programs like it is to move the focus of care for people with advanced illness out of the hospital and into home and community. This fulfills the Triple Aim vision set forth in 2008 by former CMS Administrator Don Berwick14:

- Improving health by reducing inpatient care that does not achieve person-centered goals or reduce overall mortality

- Improving care by basing it on the values and goals of people dealing with serious chronic illness

- Reducing costs by preventing unwanted hospital care

Sutter Health, a system that is on its way to becoming fully clinically integrated, was a logical choice for launching AIM because its hospitals are forming relationships with physician groups and home care providers. This integration process is supported nationally by CMS and CMMI, which are promoting new models of care and reimbursement such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments.

Nonintegrated hospitals and other provider groups can move in this same direction. AIM establishes key care coordination roles in each setting of care such as in hospitals and physician offices, as well as in the home care–based team and providers. The AIM care model emphasizes close coordination of clinical activities and communications, and integrates these with hospital and medical group operations. These provider groups can move strategically toward becoming “virtual ACOs” by coordinating care for people with advanced illness, who comprise the most vulnerable and costly segment of the US population and increasingly impact Medicare expenditures.

Changes in federal policy will be needed to facilitate national implementation of AIM-like programs. If ACOs and bundled payments were to be implemented overnight, the person-centered, cost-saving advantages of AIM would be obvious. However, until shared risk/shared savings models replace fee-for-service reimbursement, new payment policies will be needed on an interim basis to cover the costs of currently nonreimbursed care management services. This could be arranged through a per-enrollee-per-month payment or shared savings models tied to specific quality and utilization outcomes.

Simplification of regulatory requirements to better serve persons with advancing illness and to reduce the burden on providers operating such programs would be valuable. The pattern or progression of advancing chronic illness requires ongoing coordination in order to maintain a higher quality of life and symptom management. Current regulations and requirements foster an episodic focus in the home, as well in the hospital and physician’s office, which is not in alignment with the experience of persons living with advancing illness.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid program: conditions of participation. Federal Register 2008; 73:32088–32219.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. National Consensus Project Web site. http:www.nationalconsensusproject.org. Published 2009. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- Medicare hospice benefits. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/02154.pdf. Revised August 2012. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- A national framework and preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality. A consensus report. National Quality Forum Web site. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2006/12/A_National_Framework_and_Preferred_Practices_for_Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Quality.aspx. Published 2006. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- Michal MH, Pekarske MSL. Palliative care checklist: selected regulatory and risk management considerations. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Web site. http://www.nhpco.org/fles/public/palliativecare/pcchecklist.pdf. Published April 17, 2006. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Raffa CA. Palliative care: the legal and regulatory requirements. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Web site. http://www.nhpco.org/files/public/palliativecare/legal_regulatorypart2.pdf. Published December 22, 2003. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- In-home palliative care allows more patients to die at home, leading to higher satisfaction and lower acute care utilization and costs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Care Innovations Exchange Web site. http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=2366. Published March 2, 2009. Updated November 07, 2012. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:993–1000.

- Enguidanos SM, Cherin D, Brumley R. Home-based palliative care study: site of death, and costs of medical care for patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2005; 1:37–56.

- Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med 2003; 6:715–724.

- Brumley RD, Hillary K. The TriCentral Palliative Care Program Toolkit. 1st ed. MyWhatever Web site. http://www.mywhatever.com/cifwriter/content/22/fles/sorostoolkitfnal120902.doc. Published 2002. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Meyer H. Innovation profile: changing the conversation in California about care near the end of life. Health Aff 2011; 30:390–393.

- Health Care Innovation Awards. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation Web site. http://innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/Innovation-Awards/california.html. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Berwick DJ, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff 2008; 27:759–769.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid program: conditions of participation. Federal Register 2008; 73:32088–32219.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. National Consensus Project Web site. http:www.nationalconsensusproject.org. Published 2009. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- Medicare hospice benefits. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/02154.pdf. Revised August 2012. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- A national framework and preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality. A consensus report. National Quality Forum Web site. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2006/12/A_National_Framework_and_Preferred_Practices_for_Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Quality.aspx. Published 2006. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- Michal MH, Pekarske MSL. Palliative care checklist: selected regulatory and risk management considerations. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Web site. http://www.nhpco.org/fles/public/palliativecare/pcchecklist.pdf. Published April 17, 2006. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Raffa CA. Palliative care: the legal and regulatory requirements. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Web site. http://www.nhpco.org/files/public/palliativecare/legal_regulatorypart2.pdf. Published December 22, 2003. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- In-home palliative care allows more patients to die at home, leading to higher satisfaction and lower acute care utilization and costs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Care Innovations Exchange Web site. http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=2366. Published March 2, 2009. Updated November 07, 2012. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:993–1000.

- Enguidanos SM, Cherin D, Brumley R. Home-based palliative care study: site of death, and costs of medical care for patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2005; 1:37–56.

- Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med 2003; 6:715–724.

- Brumley RD, Hillary K. The TriCentral Palliative Care Program Toolkit. 1st ed. MyWhatever Web site. http://www.mywhatever.com/cifwriter/content/22/fles/sorostoolkitfnal120902.doc. Published 2002. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Meyer H. Innovation profile: changing the conversation in California about care near the end of life. Health Aff 2011; 30:390–393.

- Health Care Innovation Awards. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation Web site. http://innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/Innovation-Awards/california.html. Accessed November 14, 2012.

- Berwick DJ, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff 2008; 27:759–769.