User login

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

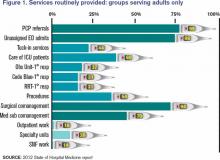

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.