User login

State of Hospital Medicine Report an Evaluation Tool for Hospital Medicine Groups

I think my team of hospitalists is probably tired of hearing my sports analogies. But as I look at the State of Hospital Medicine 2014 report (SOHM), I cannot help but see relationships to athletics.

When you think about football, you automatically contemplate the scope of a particular team and the context of the upcoming season. What are the strengths of the team—do we emphasize offense or defense or special teams? How about the variety of formations or the scheduling and strength of opponents? How about the depth of our roster—what is the talent level available? How do we compare to other teams?

How in the world does this relate to the SOHM? It gives us a chance to evaluate our own hospital medicine groups (HMGs) in the context of the other HMGs across the country. When I look at scope of services and, particularly, the data from Figure 3.1, I am struck with the breadth of the range of services in which HMGs engage. Certainly, our core identity as hospitalists includes admitting referral patients and unassigned patients, but, as of 2014, nearly 90% of hospitalist groups are also managing and co-managing surgical and medical subspecialty patients. To my eyes, the big change since 2012 is the 20% increase in the number of HMGs medically co-managing medical subspecialty patients.

There are some newcomers to our roster, as well—the palliative care and post-acute care work being done by 15% and 25% of our groups, respectively. Particularly striking is the fact that one quarter of HMGs are involved in post-acute care, follow-up clinics, nursing homes, and the like.

My take on this is that factors such as increased complexity of hospitalized patients with lean length of stay and higher acuity needs at discharge transition are driving the need for a measure of continuity and expertise post discharge that may best be provided by HMGs. The trending of the post-acute care challenges/opportunities will certainly be worth watching—sort of like a rookie player who is having a big impact.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution.

—William A. Landis, MD, FHM

Not surprisingly, nighttime admissions work continues to gain traction. Nearly 60% of HMGs are performing nighttime admissions.

In my regional chapter, we recently heard a presentation on “nocturnists.” An interesting contention that caught my attention was that the nocturnist viewed herself as providing expert clinical care during off-hours—particularly at night—and that she was looking to increase the value and not just “put her finger in the dike,” so to speak, until the cavalry arrived at daybreak. As HMG responsibilities increase during the off-hours, I am thinking that my colleague is right: We are going to have to increase our depth and strength at this particular position so that we might actually become known as the “nighttime experts.” I look for this trend to continue.

Finally, I am drawn to the data on care of patients in the ICU, a number that continues to rise—almost 70% of HMGs now. Meanwhile, procedures have dipped to 33% from 53% in the last report. At first, it seemed a little bit puzzling to me that as involvement in the ICUs seemed to increase, procedures diminished. My anecdotal experience is that most of my procedures occurred on patients who had intensive care requirements. Nonetheless, many hospitalists I have talked to seem to believe that the requirement/expectation of imaging in the performance of more and more invasive procedures—now a standard of care— has increasingly driven procedures to specialized areas of the hospital such as imaging/radiology departments. There may also be a net decrease in the number of procedures performed as more noninvasive diagnostic modalities provide satisfactory information.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution. It may make sense for others to be doing procedures. Whatever the cause, my guess is these two trends may continue.

Diving deeper into the granularity of the report will lead the reader to discover subtle differences and trends. Academics, pediatric hospitalists, and independent HMGs all have some nuances, not to mention regional variation. You will have to dig into the report yourself to explore.

Just as there is a freshness to every new sports season, there is a freshness to reviewing the information from the SOHM reports, and evaluating the scope of service is always an exciting moment.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

I think my team of hospitalists is probably tired of hearing my sports analogies. But as I look at the State of Hospital Medicine 2014 report (SOHM), I cannot help but see relationships to athletics.

When you think about football, you automatically contemplate the scope of a particular team and the context of the upcoming season. What are the strengths of the team—do we emphasize offense or defense or special teams? How about the variety of formations or the scheduling and strength of opponents? How about the depth of our roster—what is the talent level available? How do we compare to other teams?

How in the world does this relate to the SOHM? It gives us a chance to evaluate our own hospital medicine groups (HMGs) in the context of the other HMGs across the country. When I look at scope of services and, particularly, the data from Figure 3.1, I am struck with the breadth of the range of services in which HMGs engage. Certainly, our core identity as hospitalists includes admitting referral patients and unassigned patients, but, as of 2014, nearly 90% of hospitalist groups are also managing and co-managing surgical and medical subspecialty patients. To my eyes, the big change since 2012 is the 20% increase in the number of HMGs medically co-managing medical subspecialty patients.

There are some newcomers to our roster, as well—the palliative care and post-acute care work being done by 15% and 25% of our groups, respectively. Particularly striking is the fact that one quarter of HMGs are involved in post-acute care, follow-up clinics, nursing homes, and the like.

My take on this is that factors such as increased complexity of hospitalized patients with lean length of stay and higher acuity needs at discharge transition are driving the need for a measure of continuity and expertise post discharge that may best be provided by HMGs. The trending of the post-acute care challenges/opportunities will certainly be worth watching—sort of like a rookie player who is having a big impact.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution.

—William A. Landis, MD, FHM

Not surprisingly, nighttime admissions work continues to gain traction. Nearly 60% of HMGs are performing nighttime admissions.

In my regional chapter, we recently heard a presentation on “nocturnists.” An interesting contention that caught my attention was that the nocturnist viewed herself as providing expert clinical care during off-hours—particularly at night—and that she was looking to increase the value and not just “put her finger in the dike,” so to speak, until the cavalry arrived at daybreak. As HMG responsibilities increase during the off-hours, I am thinking that my colleague is right: We are going to have to increase our depth and strength at this particular position so that we might actually become known as the “nighttime experts.” I look for this trend to continue.

Finally, I am drawn to the data on care of patients in the ICU, a number that continues to rise—almost 70% of HMGs now. Meanwhile, procedures have dipped to 33% from 53% in the last report. At first, it seemed a little bit puzzling to me that as involvement in the ICUs seemed to increase, procedures diminished. My anecdotal experience is that most of my procedures occurred on patients who had intensive care requirements. Nonetheless, many hospitalists I have talked to seem to believe that the requirement/expectation of imaging in the performance of more and more invasive procedures—now a standard of care— has increasingly driven procedures to specialized areas of the hospital such as imaging/radiology departments. There may also be a net decrease in the number of procedures performed as more noninvasive diagnostic modalities provide satisfactory information.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution. It may make sense for others to be doing procedures. Whatever the cause, my guess is these two trends may continue.

Diving deeper into the granularity of the report will lead the reader to discover subtle differences and trends. Academics, pediatric hospitalists, and independent HMGs all have some nuances, not to mention regional variation. You will have to dig into the report yourself to explore.

Just as there is a freshness to every new sports season, there is a freshness to reviewing the information from the SOHM reports, and evaluating the scope of service is always an exciting moment.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

I think my team of hospitalists is probably tired of hearing my sports analogies. But as I look at the State of Hospital Medicine 2014 report (SOHM), I cannot help but see relationships to athletics.

When you think about football, you automatically contemplate the scope of a particular team and the context of the upcoming season. What are the strengths of the team—do we emphasize offense or defense or special teams? How about the variety of formations or the scheduling and strength of opponents? How about the depth of our roster—what is the talent level available? How do we compare to other teams?

How in the world does this relate to the SOHM? It gives us a chance to evaluate our own hospital medicine groups (HMGs) in the context of the other HMGs across the country. When I look at scope of services and, particularly, the data from Figure 3.1, I am struck with the breadth of the range of services in which HMGs engage. Certainly, our core identity as hospitalists includes admitting referral patients and unassigned patients, but, as of 2014, nearly 90% of hospitalist groups are also managing and co-managing surgical and medical subspecialty patients. To my eyes, the big change since 2012 is the 20% increase in the number of HMGs medically co-managing medical subspecialty patients.

There are some newcomers to our roster, as well—the palliative care and post-acute care work being done by 15% and 25% of our groups, respectively. Particularly striking is the fact that one quarter of HMGs are involved in post-acute care, follow-up clinics, nursing homes, and the like.

My take on this is that factors such as increased complexity of hospitalized patients with lean length of stay and higher acuity needs at discharge transition are driving the need for a measure of continuity and expertise post discharge that may best be provided by HMGs. The trending of the post-acute care challenges/opportunities will certainly be worth watching—sort of like a rookie player who is having a big impact.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution.

—William A. Landis, MD, FHM

Not surprisingly, nighttime admissions work continues to gain traction. Nearly 60% of HMGs are performing nighttime admissions.

In my regional chapter, we recently heard a presentation on “nocturnists.” An interesting contention that caught my attention was that the nocturnist viewed herself as providing expert clinical care during off-hours—particularly at night—and that she was looking to increase the value and not just “put her finger in the dike,” so to speak, until the cavalry arrived at daybreak. As HMG responsibilities increase during the off-hours, I am thinking that my colleague is right: We are going to have to increase our depth and strength at this particular position so that we might actually become known as the “nighttime experts.” I look for this trend to continue.

Finally, I am drawn to the data on care of patients in the ICU, a number that continues to rise—almost 70% of HMGs now. Meanwhile, procedures have dipped to 33% from 53% in the last report. At first, it seemed a little bit puzzling to me that as involvement in the ICUs seemed to increase, procedures diminished. My anecdotal experience is that most of my procedures occurred on patients who had intensive care requirements. Nonetheless, many hospitalists I have talked to seem to believe that the requirement/expectation of imaging in the performance of more and more invasive procedures—now a standard of care— has increasingly driven procedures to specialized areas of the hospital such as imaging/radiology departments. There may also be a net decrease in the number of procedures performed as more noninvasive diagnostic modalities provide satisfactory information.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution. It may make sense for others to be doing procedures. Whatever the cause, my guess is these two trends may continue.

Diving deeper into the granularity of the report will lead the reader to discover subtle differences and trends. Academics, pediatric hospitalists, and independent HMGs all have some nuances, not to mention regional variation. You will have to dig into the report yourself to explore.

Just as there is a freshness to every new sports season, there is a freshness to reviewing the information from the SOHM reports, and evaluating the scope of service is always an exciting moment.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Inside Hospitalists' Evolving Scope of Practice

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

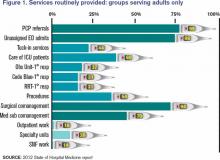

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.