User login

Tubulovillous adenoma within a colonic interposition

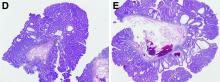

In addition to the source of the bleeding from peptic ulcer disease, the upper endoscopy revealed a large adenomatous polyp along with evidence of significant diverticular disease throughout the interposed colon. The polyp was later resected completely and histopathologic evaluation confirmed the polyp to be a tubulovillous adenoma without dysplasia (Figures D, E).

Esophageal replacement by colonic interposition is a rare surgical procedure typically only used in advanced esophageal cancers, end-stage stricturing disease, or severe caustic ingestions.1 Because of the scarcity of cases, there is little known regarding the long-term outcomes of the procedure.1

There are a growing number of reports demonstrating the presence of colon polyps within the interposed colon.2,3 These polyps range from simple adenomas to high-grade adenocarcinomas.2,3 In the majority of cases, the interposition procedure was performed later in the patient’s life, leading to the potential that the polyp or subsequent adenocarcinoma arose from a missed lesion. However, in our case the interposition was performed in adolescence, more than 50 years before presentation, strongly suggesting that the lesion likely occurred de novo.

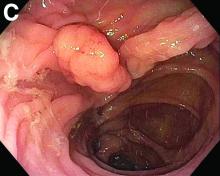

Fecal retention is commonly thought to contribute toward polyp development and diverticula in the colon, but in the case of our patient the segment of colon used for his neoesophagus would have only been exposed to stool until adolescence. It is possible that significant stasis of food owing to poor peristaltic activity in the interposed colonic segment and the presence of diverticula may have both contributed to polyp development. The fact that diverticular pouches are identified directly under the polyp would seem to support the role of food retention in polyp formation (Figures B, C). Regardless of the inciting event, this case demonstrates that the molecular pathogenesis of colon polyp formation is likely preserved, irrespective of the presence of stool or the physical location of the colon.

Had our patient not received an endoscopy for his GI bleed, the adenomatous polyp would not have been identified and removed, and likely would have continued to progress into adenocarcinoma.

Given our findings, gastroenterologists should be aware of this condition in this patient population and long-term surveillance endoscopies should be considered in all patients with colonic interpositions.

References

1. Barbosa B. et al. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy264.

2. Fisher R.A. et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-10.

3. Ramage L. et al. Surgery. 2012;10:304-5.

Tubulovillous adenoma within a colonic interposition

In addition to the source of the bleeding from peptic ulcer disease, the upper endoscopy revealed a large adenomatous polyp along with evidence of significant diverticular disease throughout the interposed colon. The polyp was later resected completely and histopathologic evaluation confirmed the polyp to be a tubulovillous adenoma without dysplasia (Figures D, E).

Esophageal replacement by colonic interposition is a rare surgical procedure typically only used in advanced esophageal cancers, end-stage stricturing disease, or severe caustic ingestions.1 Because of the scarcity of cases, there is little known regarding the long-term outcomes of the procedure.1

There are a growing number of reports demonstrating the presence of colon polyps within the interposed colon.2,3 These polyps range from simple adenomas to high-grade adenocarcinomas.2,3 In the majority of cases, the interposition procedure was performed later in the patient’s life, leading to the potential that the polyp or subsequent adenocarcinoma arose from a missed lesion. However, in our case the interposition was performed in adolescence, more than 50 years before presentation, strongly suggesting that the lesion likely occurred de novo.

Fecal retention is commonly thought to contribute toward polyp development and diverticula in the colon, but in the case of our patient the segment of colon used for his neoesophagus would have only been exposed to stool until adolescence. It is possible that significant stasis of food owing to poor peristaltic activity in the interposed colonic segment and the presence of diverticula may have both contributed to polyp development. The fact that diverticular pouches are identified directly under the polyp would seem to support the role of food retention in polyp formation (Figures B, C). Regardless of the inciting event, this case demonstrates that the molecular pathogenesis of colon polyp formation is likely preserved, irrespective of the presence of stool or the physical location of the colon.

Had our patient not received an endoscopy for his GI bleed, the adenomatous polyp would not have been identified and removed, and likely would have continued to progress into adenocarcinoma.

Given our findings, gastroenterologists should be aware of this condition in this patient population and long-term surveillance endoscopies should be considered in all patients with colonic interpositions.

References

1. Barbosa B. et al. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy264.

2. Fisher R.A. et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-10.

3. Ramage L. et al. Surgery. 2012;10:304-5.

Tubulovillous adenoma within a colonic interposition

In addition to the source of the bleeding from peptic ulcer disease, the upper endoscopy revealed a large adenomatous polyp along with evidence of significant diverticular disease throughout the interposed colon. The polyp was later resected completely and histopathologic evaluation confirmed the polyp to be a tubulovillous adenoma without dysplasia (Figures D, E).

Esophageal replacement by colonic interposition is a rare surgical procedure typically only used in advanced esophageal cancers, end-stage stricturing disease, or severe caustic ingestions.1 Because of the scarcity of cases, there is little known regarding the long-term outcomes of the procedure.1

There are a growing number of reports demonstrating the presence of colon polyps within the interposed colon.2,3 These polyps range from simple adenomas to high-grade adenocarcinomas.2,3 In the majority of cases, the interposition procedure was performed later in the patient’s life, leading to the potential that the polyp or subsequent adenocarcinoma arose from a missed lesion. However, in our case the interposition was performed in adolescence, more than 50 years before presentation, strongly suggesting that the lesion likely occurred de novo.

Fecal retention is commonly thought to contribute toward polyp development and diverticula in the colon, but in the case of our patient the segment of colon used for his neoesophagus would have only been exposed to stool until adolescence. It is possible that significant stasis of food owing to poor peristaltic activity in the interposed colonic segment and the presence of diverticula may have both contributed to polyp development. The fact that diverticular pouches are identified directly under the polyp would seem to support the role of food retention in polyp formation (Figures B, C). Regardless of the inciting event, this case demonstrates that the molecular pathogenesis of colon polyp formation is likely preserved, irrespective of the presence of stool or the physical location of the colon.

Had our patient not received an endoscopy for his GI bleed, the adenomatous polyp would not have been identified and removed, and likely would have continued to progress into adenocarcinoma.

Given our findings, gastroenterologists should be aware of this condition in this patient population and long-term surveillance endoscopies should be considered in all patients with colonic interpositions.

References

1. Barbosa B. et al. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy264.

2. Fisher R.A. et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-10.

3. Ramage L. et al. Surgery. 2012;10:304-5.

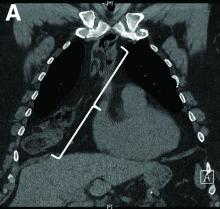

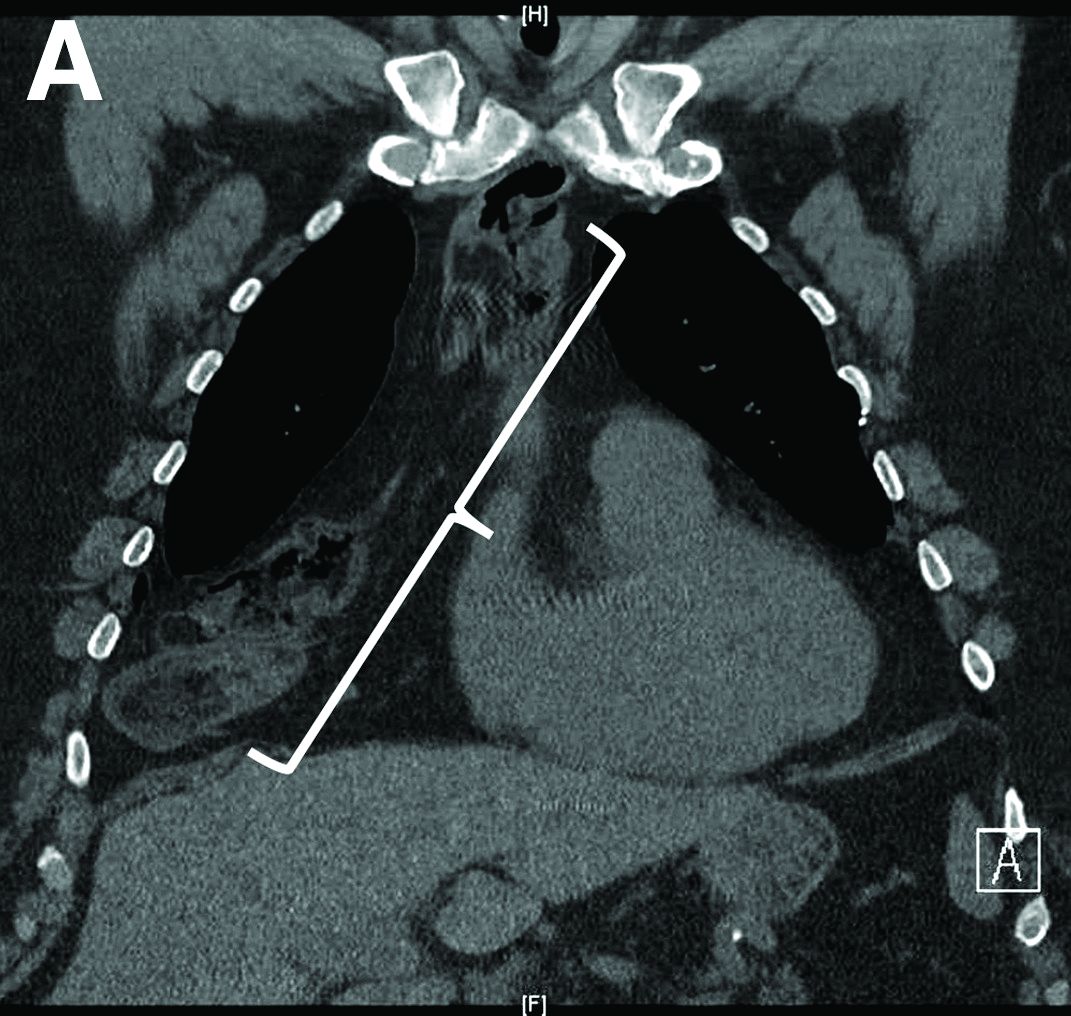

Nine months before his current presentation, he was evaluated for episodic dysphagia with associated prandial and postprandial chest discomfort and shortness of breath, which he reported had been gradually worsening over the past 20 years. The patient had undergone an exhaustive cardiopulmonary evaluation with cross-sectional imaging (Figure A, neoesophagus bracketed) and it was suspected that his symptoms were partially explained by retained food in his neoesophagus. A promotility agent was prescribed but no intervention was performed.

The patient was hemodynamically stabilized with aggressive fluid resuscitation and blood products. An urgent bedside esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed. An ulcer with a visible vessel was identified in the duodenal bulb and treated with both mechanical clipping and cauterization. However, incidental findings were noted within the esophagus (Figures B, C).

Based on the clinical history, what is the most likely underlying etiology for the incidental findings in the esophagus?