User login

The serendipitous discovery of medications that can improve mood transformed depression treatment more than 50 years ago.1 Most antidepressants produced since then could be called “me-too” medications because they all work by affecting the release of monoamines—serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine—which, in turn, modulate the activity of neurons that release glutamate.

Weeks may pass before antidepressants’ effect on monoamine-releasing neurons produces a therapeutic benefit, however, leaving many patients impaired or even suicidal. This delayed onset of action might be explained by antidepressants’ indirect blockade of glutamate. The route to more rapid results, therefore, might be to cut out the monoamine middlemen.

Glutamate clues

Glutamate, instead of monoamines, might offer a more direct means to affect mood and could be a new target for antidepressant treatment:2

- Positron-emission tomography of neuron function in depressed patients shows abnormal activity in neurons that release glutamate—so-called glutamate neurons.

- Approximately 60 % of neurons are glutamate neurons, the largest network of neurons in the brain.

- Increased glutamate activity is seen in depressed patients.

- Animal studies have shown that blocking the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor—1 of 3 types of glutamate receptors—decreases depressive behavior.

- Chronic administration of antidepressant medication reduces the expression of NMDA receptors.

Rapid glutamate blockade

Prompted by evidence that glutamate may be involved in mood disorders, researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health designed a study to determine if blocking the NMDA receptor can produce a rapid antidepressant effect.3 They chose the agent ketamine for this study because of its potent affinity for the NMDA receptor.

Ketamine was developed in the 1960s as a general anaesthetic, and its use in the United States is limited almost exclusively to veterinary medicine. The drug’s propensity to induce perceptual disturbances limits its clinical use but enhances its illicit use.

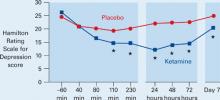

Eighteen patients with treatment-resistant depression were enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. After 2 weeks without medication, they received a single infusion of IV ketamine or placebo. One week later they received the alternate intervention. Changes in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores were assessed after each infusion.

Figure Decrease in depressive symptoms with IV ketamine

* = P <0.05

Patients who received ketamine (blue) showed a marked reduction of depressive symptoms within 2 hours compared with those who received placebo (red).

Source: Reference 3Patients receiving ketamine showed a robust and sustained reduction in depressive symptoms compared with placebo within 110 minutes (Figure). “To our knowledge,” the authors wrote, “there has never been a report of any other drug or somatic treatment—such as sleep deprivation, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, antidepressant, dexamethasone, or electroconvulsive therapy—that results in such a dramatic rapid and prolonged response with a single administration.”

Seventy-one percent of patients responded to IV ketamine within 24 hours, which is comparable to reported response rates after 8 weeks with oral antidepressants such as bupropion (62%), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (63%), and venlafaxine (65%).4,5

Caution and caveats

Despite these “dramatic” results, we must be cautious about extrapolating too much from this small study. Glutamate blockers such as ketamine can have serious adverse effects—including psychosis—and patients may not tolerate long-term interventions. Likewise, oral administration of memantine—another NMDA blocker—in a double-blind study did not effectively treat depression.6 Finally, subjects in the ketamine trial had chronic, treatment-resistant depression, and the results might not apply to other forms of depression.

The results suggest the possibility of a new option for depression treatment, however. Specifically, this option could expedite response and “jump-start” treatment through a novel mechanism so that persons with depression can get back on their feet more rapidly.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Ketamine • Ketalar

- Memantine • Namenda

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Higgins ES, George MS. Neuroscientific foundations of clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. In press.

2. Kugaya A, Sanacora G. Beyond monoamines: glutamatergic function in mood disorders. CNS Spectrums 2005;10(10):808-19.

3. Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63(8):856-64.

4. Thase ME, Haight BR, Richard N, et al. Remission rates following antidepressant therapy with bupropion or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of original data from 7 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(8):974-81.

5. Entsuah AR, Huang H, Thase ME. Response and remission rates in different subpopulations with major depressive disorder administered venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(11):869-77.

6. Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Quiroz JA, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of memantine in the treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(1):153-5.

The serendipitous discovery of medications that can improve mood transformed depression treatment more than 50 years ago.1 Most antidepressants produced since then could be called “me-too” medications because they all work by affecting the release of monoamines—serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine—which, in turn, modulate the activity of neurons that release glutamate.

Weeks may pass before antidepressants’ effect on monoamine-releasing neurons produces a therapeutic benefit, however, leaving many patients impaired or even suicidal. This delayed onset of action might be explained by antidepressants’ indirect blockade of glutamate. The route to more rapid results, therefore, might be to cut out the monoamine middlemen.

Glutamate clues

Glutamate, instead of monoamines, might offer a more direct means to affect mood and could be a new target for antidepressant treatment:2

- Positron-emission tomography of neuron function in depressed patients shows abnormal activity in neurons that release glutamate—so-called glutamate neurons.

- Approximately 60 % of neurons are glutamate neurons, the largest network of neurons in the brain.

- Increased glutamate activity is seen in depressed patients.

- Animal studies have shown that blocking the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor—1 of 3 types of glutamate receptors—decreases depressive behavior.

- Chronic administration of antidepressant medication reduces the expression of NMDA receptors.

Rapid glutamate blockade

Prompted by evidence that glutamate may be involved in mood disorders, researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health designed a study to determine if blocking the NMDA receptor can produce a rapid antidepressant effect.3 They chose the agent ketamine for this study because of its potent affinity for the NMDA receptor.

Ketamine was developed in the 1960s as a general anaesthetic, and its use in the United States is limited almost exclusively to veterinary medicine. The drug’s propensity to induce perceptual disturbances limits its clinical use but enhances its illicit use.

Eighteen patients with treatment-resistant depression were enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. After 2 weeks without medication, they received a single infusion of IV ketamine or placebo. One week later they received the alternate intervention. Changes in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores were assessed after each infusion.

Figure Decrease in depressive symptoms with IV ketamine

* = P <0.05

Patients who received ketamine (blue) showed a marked reduction of depressive symptoms within 2 hours compared with those who received placebo (red).

Source: Reference 3Patients receiving ketamine showed a robust and sustained reduction in depressive symptoms compared with placebo within 110 minutes (Figure). “To our knowledge,” the authors wrote, “there has never been a report of any other drug or somatic treatment—such as sleep deprivation, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, antidepressant, dexamethasone, or electroconvulsive therapy—that results in such a dramatic rapid and prolonged response with a single administration.”

Seventy-one percent of patients responded to IV ketamine within 24 hours, which is comparable to reported response rates after 8 weeks with oral antidepressants such as bupropion (62%), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (63%), and venlafaxine (65%).4,5

Caution and caveats

Despite these “dramatic” results, we must be cautious about extrapolating too much from this small study. Glutamate blockers such as ketamine can have serious adverse effects—including psychosis—and patients may not tolerate long-term interventions. Likewise, oral administration of memantine—another NMDA blocker—in a double-blind study did not effectively treat depression.6 Finally, subjects in the ketamine trial had chronic, treatment-resistant depression, and the results might not apply to other forms of depression.

The results suggest the possibility of a new option for depression treatment, however. Specifically, this option could expedite response and “jump-start” treatment through a novel mechanism so that persons with depression can get back on their feet more rapidly.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Ketamine • Ketalar

- Memantine • Namenda

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

The serendipitous discovery of medications that can improve mood transformed depression treatment more than 50 years ago.1 Most antidepressants produced since then could be called “me-too” medications because they all work by affecting the release of monoamines—serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine—which, in turn, modulate the activity of neurons that release glutamate.

Weeks may pass before antidepressants’ effect on monoamine-releasing neurons produces a therapeutic benefit, however, leaving many patients impaired or even suicidal. This delayed onset of action might be explained by antidepressants’ indirect blockade of glutamate. The route to more rapid results, therefore, might be to cut out the monoamine middlemen.

Glutamate clues

Glutamate, instead of monoamines, might offer a more direct means to affect mood and could be a new target for antidepressant treatment:2

- Positron-emission tomography of neuron function in depressed patients shows abnormal activity in neurons that release glutamate—so-called glutamate neurons.

- Approximately 60 % of neurons are glutamate neurons, the largest network of neurons in the brain.

- Increased glutamate activity is seen in depressed patients.

- Animal studies have shown that blocking the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor—1 of 3 types of glutamate receptors—decreases depressive behavior.

- Chronic administration of antidepressant medication reduces the expression of NMDA receptors.

Rapid glutamate blockade

Prompted by evidence that glutamate may be involved in mood disorders, researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health designed a study to determine if blocking the NMDA receptor can produce a rapid antidepressant effect.3 They chose the agent ketamine for this study because of its potent affinity for the NMDA receptor.

Ketamine was developed in the 1960s as a general anaesthetic, and its use in the United States is limited almost exclusively to veterinary medicine. The drug’s propensity to induce perceptual disturbances limits its clinical use but enhances its illicit use.

Eighteen patients with treatment-resistant depression were enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. After 2 weeks without medication, they received a single infusion of IV ketamine or placebo. One week later they received the alternate intervention. Changes in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores were assessed after each infusion.

Figure Decrease in depressive symptoms with IV ketamine

* = P <0.05

Patients who received ketamine (blue) showed a marked reduction of depressive symptoms within 2 hours compared with those who received placebo (red).

Source: Reference 3Patients receiving ketamine showed a robust and sustained reduction in depressive symptoms compared with placebo within 110 minutes (Figure). “To our knowledge,” the authors wrote, “there has never been a report of any other drug or somatic treatment—such as sleep deprivation, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, antidepressant, dexamethasone, or electroconvulsive therapy—that results in such a dramatic rapid and prolonged response with a single administration.”

Seventy-one percent of patients responded to IV ketamine within 24 hours, which is comparable to reported response rates after 8 weeks with oral antidepressants such as bupropion (62%), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (63%), and venlafaxine (65%).4,5

Caution and caveats

Despite these “dramatic” results, we must be cautious about extrapolating too much from this small study. Glutamate blockers such as ketamine can have serious adverse effects—including psychosis—and patients may not tolerate long-term interventions. Likewise, oral administration of memantine—another NMDA blocker—in a double-blind study did not effectively treat depression.6 Finally, subjects in the ketamine trial had chronic, treatment-resistant depression, and the results might not apply to other forms of depression.

The results suggest the possibility of a new option for depression treatment, however. Specifically, this option could expedite response and “jump-start” treatment through a novel mechanism so that persons with depression can get back on their feet more rapidly.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Ketamine • Ketalar

- Memantine • Namenda

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Higgins ES, George MS. Neuroscientific foundations of clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. In press.

2. Kugaya A, Sanacora G. Beyond monoamines: glutamatergic function in mood disorders. CNS Spectrums 2005;10(10):808-19.

3. Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63(8):856-64.

4. Thase ME, Haight BR, Richard N, et al. Remission rates following antidepressant therapy with bupropion or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of original data from 7 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(8):974-81.

5. Entsuah AR, Huang H, Thase ME. Response and remission rates in different subpopulations with major depressive disorder administered venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(11):869-77.

6. Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Quiroz JA, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of memantine in the treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(1):153-5.

1. Higgins ES, George MS. Neuroscientific foundations of clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. In press.

2. Kugaya A, Sanacora G. Beyond monoamines: glutamatergic function in mood disorders. CNS Spectrums 2005;10(10):808-19.

3. Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63(8):856-64.

4. Thase ME, Haight BR, Richard N, et al. Remission rates following antidepressant therapy with bupropion or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of original data from 7 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(8):974-81.

5. Entsuah AR, Huang H, Thase ME. Response and remission rates in different subpopulations with major depressive disorder administered venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(11):869-77.

6. Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Quiroz JA, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of memantine in the treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(1):153-5.