User login

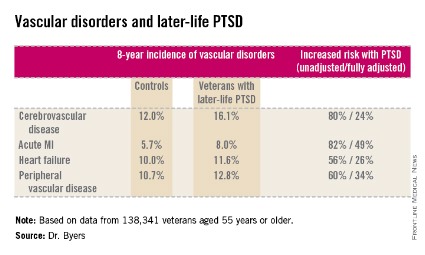

ORLANDO – Military veterans aged 55 years or older with current posttraumatic stress disorder are at significantly higher risk of developing new-onset vascular disease than are those without PTSD, according to a very large national longitudinal study.

"This study suggests the need for greater monitoring and treatment of PTSD in older veterans to assist in the prevention of vascular disorders," Amy L. Byers, Ph.D., said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

She reported on 138,341 veterans aged 55 years or older who were free of known vascular disease at baseline. During 8 years of follow-up, those with PTSD had significantly higher rates of incident cerebrovascular disease, acute MI, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease than did those without PTSD, even after adjustment for demographics, comorbid diabetes, hypertension, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, traumatic brain injury, dementia, substance use disorders, and psychiatric diagnoses. The fully adjusted increased risk of each of the forms of vascular disease under study still remained significant at P less than .001, noted Dr. Byers, an epidemiologist in the psychiatry department at the University of California, San Francisco.

In a separate study led by Dr. Byers, PTSD in the general population with onset prior to and persistence beyond age 55 was a powerful independent predictor of global disability.

Dr. Byers’ study of older veterans was funded by the Department of Defense. She had no disclosures.

This paper continues to strengthen a link between PTSD and inflammatory markers. Dewleen Baker of the VA health care system in San Diego reported that there was a 10-fold increase in C-reactive protein (CRP) post deployment as compared with these same soldiers predeployment CRP levels. After adjustment for battlefield experience scores and combat exposures, those patients with PTSD symptoms had elevated CRP levels of 1.0 ng/mL versus 0.7 ng/mL without postdeployment symptoms (JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:423-31). So it seems that there may be a link between PTSD negative cardiovascular outcomes. And there may be a link between PTSD and elevated CRP. So, this leaves us with at least two questions: Is elevated CRP related to increased incidence of negative cardiovascular outcomes? And, which came first, the chicken (PTSD) or the egg (elevated CRP)?

Dr. Mark A. Adelman is chief of vascular and endovascular surgery at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

This paper continues to strengthen a link between PTSD and inflammatory markers. Dewleen Baker of the VA health care system in San Diego reported that there was a 10-fold increase in C-reactive protein (CRP) post deployment as compared with these same soldiers predeployment CRP levels. After adjustment for battlefield experience scores and combat exposures, those patients with PTSD symptoms had elevated CRP levels of 1.0 ng/mL versus 0.7 ng/mL without postdeployment symptoms (JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:423-31). So it seems that there may be a link between PTSD negative cardiovascular outcomes. And there may be a link between PTSD and elevated CRP. So, this leaves us with at least two questions: Is elevated CRP related to increased incidence of negative cardiovascular outcomes? And, which came first, the chicken (PTSD) or the egg (elevated CRP)?

Dr. Mark A. Adelman is chief of vascular and endovascular surgery at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

This paper continues to strengthen a link between PTSD and inflammatory markers. Dewleen Baker of the VA health care system in San Diego reported that there was a 10-fold increase in C-reactive protein (CRP) post deployment as compared with these same soldiers predeployment CRP levels. After adjustment for battlefield experience scores and combat exposures, those patients with PTSD symptoms had elevated CRP levels of 1.0 ng/mL versus 0.7 ng/mL without postdeployment symptoms (JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:423-31). So it seems that there may be a link between PTSD negative cardiovascular outcomes. And there may be a link between PTSD and elevated CRP. So, this leaves us with at least two questions: Is elevated CRP related to increased incidence of negative cardiovascular outcomes? And, which came first, the chicken (PTSD) or the egg (elevated CRP)?

Dr. Mark A. Adelman is chief of vascular and endovascular surgery at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

ORLANDO – Military veterans aged 55 years or older with current posttraumatic stress disorder are at significantly higher risk of developing new-onset vascular disease than are those without PTSD, according to a very large national longitudinal study.

"This study suggests the need for greater monitoring and treatment of PTSD in older veterans to assist in the prevention of vascular disorders," Amy L. Byers, Ph.D., said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

She reported on 138,341 veterans aged 55 years or older who were free of known vascular disease at baseline. During 8 years of follow-up, those with PTSD had significantly higher rates of incident cerebrovascular disease, acute MI, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease than did those without PTSD, even after adjustment for demographics, comorbid diabetes, hypertension, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, traumatic brain injury, dementia, substance use disorders, and psychiatric diagnoses. The fully adjusted increased risk of each of the forms of vascular disease under study still remained significant at P less than .001, noted Dr. Byers, an epidemiologist in the psychiatry department at the University of California, San Francisco.

In a separate study led by Dr. Byers, PTSD in the general population with onset prior to and persistence beyond age 55 was a powerful independent predictor of global disability.

Dr. Byers’ study of older veterans was funded by the Department of Defense. She had no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Military veterans aged 55 years or older with current posttraumatic stress disorder are at significantly higher risk of developing new-onset vascular disease than are those without PTSD, according to a very large national longitudinal study.

"This study suggests the need for greater monitoring and treatment of PTSD in older veterans to assist in the prevention of vascular disorders," Amy L. Byers, Ph.D., said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

She reported on 138,341 veterans aged 55 years or older who were free of known vascular disease at baseline. During 8 years of follow-up, those with PTSD had significantly higher rates of incident cerebrovascular disease, acute MI, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease than did those without PTSD, even after adjustment for demographics, comorbid diabetes, hypertension, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, traumatic brain injury, dementia, substance use disorders, and psychiatric diagnoses. The fully adjusted increased risk of each of the forms of vascular disease under study still remained significant at P less than .001, noted Dr. Byers, an epidemiologist in the psychiatry department at the University of California, San Francisco.

In a separate study led by Dr. Byers, PTSD in the general population with onset prior to and persistence beyond age 55 was a powerful independent predictor of global disability.

Dr. Byers’ study of older veterans was funded by the Department of Defense. She had no disclosures.

Major finding: Military veterans with late-life posttraumatic stress disorder were 80% more likely to develop new-onset cerebrovascular disease during 8 years of follow-up than were those without PTSD. They were also 82% more likely to have a first acute myocardial infarction, 56% more likely to develop heart failure, and 60% more likely to be diagnosed with peripheral vascular disease.

Data source: This was a longitudinal observational study in 138,341 veterans aged 55 years or older who were free of known vascular disease at baseline and were followed for 8 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Byers’ study of older veterans was funded by the Department of Defense. She reported having no financial conflicts.