User login

Recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) finalized 7 recommendations on 5 topics and posted draft recommendations on an additional 10 topics. It also implemented new procedures that include posting draft recommendations for public comment (see “A new review process for the USPSTF”). This article reviews the USPSTF activity in 2011, as well as cervical cancer screening recommendations issued earlier this year.

In response to the adverse publicity from the 2009 mammogram recommendations and the increased scrutiny brought on by the affordable care act—which mandates that A and B recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task force are covered preventive services provided at no charge to the patient—the USPSTF developed and implemented a new review procedure. This is intended to increase stakeholder involvement at all steps in the process.

Last year, the USPSTF completed its rollout of this new online review process. The USPSTF now posts all draft recommendations and the evidence report supporting them on its Web site for public comment. final recommendations are posted months later after consideration of the public input. The final recommendations for the 10 topics with draft recommendations posted in 2011 are expected to be released this year.

Potential for confusion. The new process may cause confusion for family physicians. Draft recommendations will receive press coverage and may differ from the final recommendations, as happened with cervical cancer screening recommendations. Physicians will need to familiarize themselves with the process and look for final recommendations on the USPSTF Web site at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm.

2012 recommendations

Screening for cervical cancer

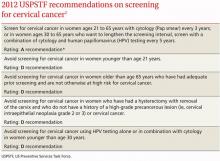

The USPSTF released its new recommendations on screening for cervical cancer in March (TABLE 1).1 The final document varied from the 2011 draft recommendations in 2 areas: the roles of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and sexual history.

- The draft issued an I statement (insufficient evidence) for the role of HPV testing. Subsequently, based on stakeholder and public comment (as well as a review of 2 large recently published studies), the USPSTF gave an A recommendation to the use of HPV testing in conjunction with cervical cytology as an option for women ages 30 years and older who want to increase the interval between screening to 5 years.2,3

- The draft stated that the age at which screening should be initiated depends on a patient’s sexual history. The final recommendations state that screening should not begin until age 21, regardless of sexual history.

TABLE 1

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

These new recommendations balance the proven benefits of cervical cytology with the harms from overscreening and are now essentially the same as those of other organizations, including the American Cancer Society, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology. They differ in minor ways from those of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Family Physicians is assessing whether to endorse them.

Importantly, the new recommendations identify individuals for whom cervical cytology should be avoided—women younger than age 21, most women older than age 65, and those who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix. A decision to stop screening after the 65th birthday depends on whether the patient has had adequate screening yielding normal findings: This is defined by the USPSTF as 3 consecutive negative cytology results (or 2 consecutive negative co-test results with cytology and HIV testing) within 10 years of the proposed time of cessation, with the most recent test having been performed within 5 years. Avoiding cytology testing after hysterectomy is contingent on the procedure having been performed for an indication other than a high-grade precancerous lesion or cervical cancer. In addition, the recommendations advise against HPV testing in women younger than age 30, as it offers little advantage and leads to much overdiagnosis.

Liquid vs conventional cytology. As a minor point, the USPSTF says the evidence clearly shows that liquid cytology offers no advantage over conventional cytology. But it recognizes that the screening method used is often not determined by the physician.

Recommendations finalized in 2011

TABLE 2 summarizes recommendations completed by the USPSTF last year.

Neonatal gonococcal eye infection prevention

The recommendation to use topical medication (erythromycin ointment) to prevent neonatal gonococcal eye infection is an update and reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Blindness due to this disease has become rare in the United States because of the routine use of a neonatal topical antibiotic, and there is good evidence that it causes no significant harm. Its use continues to be recommended for all newborns.4

TABLE 2

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

Vision screening for children

Vision screening for preschool children can detect visual acuity problems such as amblyopia and refractive errors. A variety of screening tests are available, including visual acuity, stereoacuity, cover-uncover, Hirschberg light reflex, and auto-refractor tests (automated optical instruments that detect refractive errors). The most benefit is obtained by discovering and correcting amblyopia.

There is no evidence that detecting problems before age 3 years leads to better outcomes than detection between 3 and 5 years of age. Testing is more difficult in younger children and can yield inconclusive or false-positive results more frequently. This led the USPSTF to reaffirm vision testing once for children ages 3 to 5 years, and to state that the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation for younger children.5

Screening for osteoporosis

The recommendations indicate that all women ages 65 and older should undergo screening, although the optimal frequency of screening is not known. The clinical discussion accompanying the recommendation indicates there is reason to believe that screening men may reduce morbidity and mortality, but that sufficient evidence for or against this is lacking.6

Screening can be done with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) of the hip and lumbar spine, or quantitative ultrasonography of the calcaneus. DEXA is most commonly used, and is the basis for most treatment recommendations.

The recommendation to screen some women younger than 65 years, based on risk, is somewhat complex. The USPSTF recommends screening younger women if their 10-year risk of fracture is comparable to that of a 65-year-old white woman with no additional risk factors (a risk of 9.3% over 10 years). To calculate that risk, the USPSTF recommends using the FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment) tool developed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, Sheffield, United Kingdom, which is available free to clinicians and the public (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/).

Screening for testicular cancer

The recommendation against screening for testicular cancer may surprise many physicians, even though it is a reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Testicular cancer is uncommon (5 cases per 100,000 males per year) and treatment is successful in a large proportion of patients, regardless of the stage at which it is discovered. Patients or their partners discover these tumors in time for a cure and there is no evidence physician exams improve outcomes. Physician discovery of incidental and inconsequential findings such as spermatoceles and varicoceles can lead to unnecessary testing and follow-up.7

Screening for bladder cancer

The USPSTF issued an I statement for bladder cancer screening because there is little evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of available tests (urinalysis for microscopic hematuria, urine cytology, or tests for urine biomarkers) in detecting bladder cancer in asymptomatic patients. In addition, there is no evidence regarding the potential benefits of detecting asymptomatic bladder cancer.8

Current draft recommendations

The USPSTF posts recommendations on its Web site for public comment for 30 days. To see current draft recommendations, go to http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

1. USPSTF. Screening for cervical cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

2. Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:78-88.

3. Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663-672.

4. USPSTF. Ocular prophylaxis for gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsgononew.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

5. USPSTF. Screening for vision impairment in children ages 1 to 5 years. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsvsch.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

6. USPSTF. Screening for osteoporosis. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsoste.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

7. USPSTF. Screening for testicular cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstest.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

8. USPSTF. Screening for bladder cancer in adults. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsblad.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

Recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) finalized 7 recommendations on 5 topics and posted draft recommendations on an additional 10 topics. It also implemented new procedures that include posting draft recommendations for public comment (see “A new review process for the USPSTF”). This article reviews the USPSTF activity in 2011, as well as cervical cancer screening recommendations issued earlier this year.

In response to the adverse publicity from the 2009 mammogram recommendations and the increased scrutiny brought on by the affordable care act—which mandates that A and B recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task force are covered preventive services provided at no charge to the patient—the USPSTF developed and implemented a new review procedure. This is intended to increase stakeholder involvement at all steps in the process.

Last year, the USPSTF completed its rollout of this new online review process. The USPSTF now posts all draft recommendations and the evidence report supporting them on its Web site for public comment. final recommendations are posted months later after consideration of the public input. The final recommendations for the 10 topics with draft recommendations posted in 2011 are expected to be released this year.

Potential for confusion. The new process may cause confusion for family physicians. Draft recommendations will receive press coverage and may differ from the final recommendations, as happened with cervical cancer screening recommendations. Physicians will need to familiarize themselves with the process and look for final recommendations on the USPSTF Web site at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm.

2012 recommendations

Screening for cervical cancer

The USPSTF released its new recommendations on screening for cervical cancer in March (TABLE 1).1 The final document varied from the 2011 draft recommendations in 2 areas: the roles of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and sexual history.

- The draft issued an I statement (insufficient evidence) for the role of HPV testing. Subsequently, based on stakeholder and public comment (as well as a review of 2 large recently published studies), the USPSTF gave an A recommendation to the use of HPV testing in conjunction with cervical cytology as an option for women ages 30 years and older who want to increase the interval between screening to 5 years.2,3

- The draft stated that the age at which screening should be initiated depends on a patient’s sexual history. The final recommendations state that screening should not begin until age 21, regardless of sexual history.

TABLE 1

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

These new recommendations balance the proven benefits of cervical cytology with the harms from overscreening and are now essentially the same as those of other organizations, including the American Cancer Society, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology. They differ in minor ways from those of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Family Physicians is assessing whether to endorse them.

Importantly, the new recommendations identify individuals for whom cervical cytology should be avoided—women younger than age 21, most women older than age 65, and those who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix. A decision to stop screening after the 65th birthday depends on whether the patient has had adequate screening yielding normal findings: This is defined by the USPSTF as 3 consecutive negative cytology results (or 2 consecutive negative co-test results with cytology and HIV testing) within 10 years of the proposed time of cessation, with the most recent test having been performed within 5 years. Avoiding cytology testing after hysterectomy is contingent on the procedure having been performed for an indication other than a high-grade precancerous lesion or cervical cancer. In addition, the recommendations advise against HPV testing in women younger than age 30, as it offers little advantage and leads to much overdiagnosis.

Liquid vs conventional cytology. As a minor point, the USPSTF says the evidence clearly shows that liquid cytology offers no advantage over conventional cytology. But it recognizes that the screening method used is often not determined by the physician.

Recommendations finalized in 2011

TABLE 2 summarizes recommendations completed by the USPSTF last year.

Neonatal gonococcal eye infection prevention

The recommendation to use topical medication (erythromycin ointment) to prevent neonatal gonococcal eye infection is an update and reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Blindness due to this disease has become rare in the United States because of the routine use of a neonatal topical antibiotic, and there is good evidence that it causes no significant harm. Its use continues to be recommended for all newborns.4

TABLE 2

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

Vision screening for children

Vision screening for preschool children can detect visual acuity problems such as amblyopia and refractive errors. A variety of screening tests are available, including visual acuity, stereoacuity, cover-uncover, Hirschberg light reflex, and auto-refractor tests (automated optical instruments that detect refractive errors). The most benefit is obtained by discovering and correcting amblyopia.

There is no evidence that detecting problems before age 3 years leads to better outcomes than detection between 3 and 5 years of age. Testing is more difficult in younger children and can yield inconclusive or false-positive results more frequently. This led the USPSTF to reaffirm vision testing once for children ages 3 to 5 years, and to state that the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation for younger children.5

Screening for osteoporosis

The recommendations indicate that all women ages 65 and older should undergo screening, although the optimal frequency of screening is not known. The clinical discussion accompanying the recommendation indicates there is reason to believe that screening men may reduce morbidity and mortality, but that sufficient evidence for or against this is lacking.6

Screening can be done with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) of the hip and lumbar spine, or quantitative ultrasonography of the calcaneus. DEXA is most commonly used, and is the basis for most treatment recommendations.

The recommendation to screen some women younger than 65 years, based on risk, is somewhat complex. The USPSTF recommends screening younger women if their 10-year risk of fracture is comparable to that of a 65-year-old white woman with no additional risk factors (a risk of 9.3% over 10 years). To calculate that risk, the USPSTF recommends using the FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment) tool developed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, Sheffield, United Kingdom, which is available free to clinicians and the public (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/).

Screening for testicular cancer

The recommendation against screening for testicular cancer may surprise many physicians, even though it is a reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Testicular cancer is uncommon (5 cases per 100,000 males per year) and treatment is successful in a large proportion of patients, regardless of the stage at which it is discovered. Patients or their partners discover these tumors in time for a cure and there is no evidence physician exams improve outcomes. Physician discovery of incidental and inconsequential findings such as spermatoceles and varicoceles can lead to unnecessary testing and follow-up.7

Screening for bladder cancer

The USPSTF issued an I statement for bladder cancer screening because there is little evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of available tests (urinalysis for microscopic hematuria, urine cytology, or tests for urine biomarkers) in detecting bladder cancer in asymptomatic patients. In addition, there is no evidence regarding the potential benefits of detecting asymptomatic bladder cancer.8

Current draft recommendations

The USPSTF posts recommendations on its Web site for public comment for 30 days. To see current draft recommendations, go to http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

Recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) finalized 7 recommendations on 5 topics and posted draft recommendations on an additional 10 topics. It also implemented new procedures that include posting draft recommendations for public comment (see “A new review process for the USPSTF”). This article reviews the USPSTF activity in 2011, as well as cervical cancer screening recommendations issued earlier this year.

In response to the adverse publicity from the 2009 mammogram recommendations and the increased scrutiny brought on by the affordable care act—which mandates that A and B recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task force are covered preventive services provided at no charge to the patient—the USPSTF developed and implemented a new review procedure. This is intended to increase stakeholder involvement at all steps in the process.

Last year, the USPSTF completed its rollout of this new online review process. The USPSTF now posts all draft recommendations and the evidence report supporting them on its Web site for public comment. final recommendations are posted months later after consideration of the public input. The final recommendations for the 10 topics with draft recommendations posted in 2011 are expected to be released this year.

Potential for confusion. The new process may cause confusion for family physicians. Draft recommendations will receive press coverage and may differ from the final recommendations, as happened with cervical cancer screening recommendations. Physicians will need to familiarize themselves with the process and look for final recommendations on the USPSTF Web site at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm.

2012 recommendations

Screening for cervical cancer

The USPSTF released its new recommendations on screening for cervical cancer in March (TABLE 1).1 The final document varied from the 2011 draft recommendations in 2 areas: the roles of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and sexual history.

- The draft issued an I statement (insufficient evidence) for the role of HPV testing. Subsequently, based on stakeholder and public comment (as well as a review of 2 large recently published studies), the USPSTF gave an A recommendation to the use of HPV testing in conjunction with cervical cytology as an option for women ages 30 years and older who want to increase the interval between screening to 5 years.2,3

- The draft stated that the age at which screening should be initiated depends on a patient’s sexual history. The final recommendations state that screening should not begin until age 21, regardless of sexual history.

TABLE 1

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

These new recommendations balance the proven benefits of cervical cytology with the harms from overscreening and are now essentially the same as those of other organizations, including the American Cancer Society, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology. They differ in minor ways from those of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Family Physicians is assessing whether to endorse them.

Importantly, the new recommendations identify individuals for whom cervical cytology should be avoided—women younger than age 21, most women older than age 65, and those who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix. A decision to stop screening after the 65th birthday depends on whether the patient has had adequate screening yielding normal findings: This is defined by the USPSTF as 3 consecutive negative cytology results (or 2 consecutive negative co-test results with cytology and HIV testing) within 10 years of the proposed time of cessation, with the most recent test having been performed within 5 years. Avoiding cytology testing after hysterectomy is contingent on the procedure having been performed for an indication other than a high-grade precancerous lesion or cervical cancer. In addition, the recommendations advise against HPV testing in women younger than age 30, as it offers little advantage and leads to much overdiagnosis.

Liquid vs conventional cytology. As a minor point, the USPSTF says the evidence clearly shows that liquid cytology offers no advantage over conventional cytology. But it recognizes that the screening method used is often not determined by the physician.

Recommendations finalized in 2011

TABLE 2 summarizes recommendations completed by the USPSTF last year.

Neonatal gonococcal eye infection prevention

The recommendation to use topical medication (erythromycin ointment) to prevent neonatal gonococcal eye infection is an update and reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Blindness due to this disease has become rare in the United States because of the routine use of a neonatal topical antibiotic, and there is good evidence that it causes no significant harm. Its use continues to be recommended for all newborns.4

TABLE 2

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

Vision screening for children

Vision screening for preschool children can detect visual acuity problems such as amblyopia and refractive errors. A variety of screening tests are available, including visual acuity, stereoacuity, cover-uncover, Hirschberg light reflex, and auto-refractor tests (automated optical instruments that detect refractive errors). The most benefit is obtained by discovering and correcting amblyopia.

There is no evidence that detecting problems before age 3 years leads to better outcomes than detection between 3 and 5 years of age. Testing is more difficult in younger children and can yield inconclusive or false-positive results more frequently. This led the USPSTF to reaffirm vision testing once for children ages 3 to 5 years, and to state that the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation for younger children.5

Screening for osteoporosis

The recommendations indicate that all women ages 65 and older should undergo screening, although the optimal frequency of screening is not known. The clinical discussion accompanying the recommendation indicates there is reason to believe that screening men may reduce morbidity and mortality, but that sufficient evidence for or against this is lacking.6

Screening can be done with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) of the hip and lumbar spine, or quantitative ultrasonography of the calcaneus. DEXA is most commonly used, and is the basis for most treatment recommendations.

The recommendation to screen some women younger than 65 years, based on risk, is somewhat complex. The USPSTF recommends screening younger women if their 10-year risk of fracture is comparable to that of a 65-year-old white woman with no additional risk factors (a risk of 9.3% over 10 years). To calculate that risk, the USPSTF recommends using the FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment) tool developed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, Sheffield, United Kingdom, which is available free to clinicians and the public (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/).

Screening for testicular cancer

The recommendation against screening for testicular cancer may surprise many physicians, even though it is a reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Testicular cancer is uncommon (5 cases per 100,000 males per year) and treatment is successful in a large proportion of patients, regardless of the stage at which it is discovered. Patients or their partners discover these tumors in time for a cure and there is no evidence physician exams improve outcomes. Physician discovery of incidental and inconsequential findings such as spermatoceles and varicoceles can lead to unnecessary testing and follow-up.7

Screening for bladder cancer

The USPSTF issued an I statement for bladder cancer screening because there is little evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of available tests (urinalysis for microscopic hematuria, urine cytology, or tests for urine biomarkers) in detecting bladder cancer in asymptomatic patients. In addition, there is no evidence regarding the potential benefits of detecting asymptomatic bladder cancer.8

Current draft recommendations

The USPSTF posts recommendations on its Web site for public comment for 30 days. To see current draft recommendations, go to http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

1. USPSTF. Screening for cervical cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

2. Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:78-88.

3. Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663-672.

4. USPSTF. Ocular prophylaxis for gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsgononew.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

5. USPSTF. Screening for vision impairment in children ages 1 to 5 years. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsvsch.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

6. USPSTF. Screening for osteoporosis. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsoste.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

7. USPSTF. Screening for testicular cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstest.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

8. USPSTF. Screening for bladder cancer in adults. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsblad.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

1. USPSTF. Screening for cervical cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

2. Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:78-88.

3. Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663-672.

4. USPSTF. Ocular prophylaxis for gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsgononew.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

5. USPSTF. Screening for vision impairment in children ages 1 to 5 years. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsvsch.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

6. USPSTF. Screening for osteoporosis. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsoste.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

7. USPSTF. Screening for testicular cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstest.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

8. USPSTF. Screening for bladder cancer in adults. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsblad.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.