User login

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

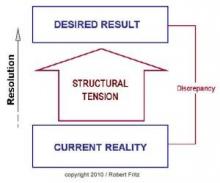

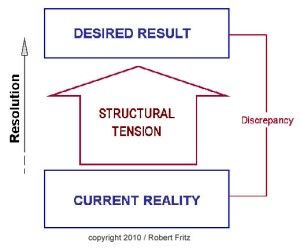

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).