User login

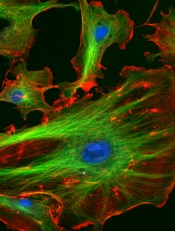

Image courtesy of NIH

Low doses of iron can modify the vascular endothelium and induce a DNA-damage response, researchers have reported in PLOS ONE.

The team observed these phenomena in vitro and said the results must be confirmed via additional research.

However, the findings suggest a need to assess the amount of iron given in standard treatments and the effects this may have on the body, according to Claire Shovlin, PhD, of Imperial College London in the UK.

Dr Shovlin and her colleagues studied human endothelial cells, adding either placebo or an iron solution of 10 micromolar, which is a similar concentration to that seen in the blood after taking an iron tablet.

Within 10 minutes, cells treated with the iron solution had activated DNA repair systems, and these were still activated 6 hours later.

“We already knew that iron could be damaging to cells in very high doses,” Dr Shovlin said. “However, in this study, we found that when we applied the kinds of levels of iron you would find in the bloodstream after taking an iron tablet, this also seemed to be able to trigger cell damage—at least in the laboratory. In other words, cells seem more sensitive to iron than we previously thought.”

“This is very early stage research, and we need more work to confirm these findings and investigate what effects this may have on the body. We are still not sure how these laboratory findings translate to blood vessels in the body.”

“However, this study helps to open the conversation about how much iron people take. At the moment, each standard iron tablet contains almost 10 times the amount of iron men are recommended to eat each day, and these dosages haven’t changed for more than 50 years. This research suggests we may need to think more carefully about how much iron we give to people, and try and tailor the dose to the patient.”

Dr Shovlin and her colleagues initially started researching this area after finding that a small proportion of people using iron tablets for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which causes abnormalities in the blood vessels, reported their nose bleeds worsened after iron treatment. ![]()

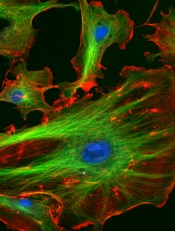

Image courtesy of NIH

Low doses of iron can modify the vascular endothelium and induce a DNA-damage response, researchers have reported in PLOS ONE.

The team observed these phenomena in vitro and said the results must be confirmed via additional research.

However, the findings suggest a need to assess the amount of iron given in standard treatments and the effects this may have on the body, according to Claire Shovlin, PhD, of Imperial College London in the UK.

Dr Shovlin and her colleagues studied human endothelial cells, adding either placebo or an iron solution of 10 micromolar, which is a similar concentration to that seen in the blood after taking an iron tablet.

Within 10 minutes, cells treated with the iron solution had activated DNA repair systems, and these were still activated 6 hours later.

“We already knew that iron could be damaging to cells in very high doses,” Dr Shovlin said. “However, in this study, we found that when we applied the kinds of levels of iron you would find in the bloodstream after taking an iron tablet, this also seemed to be able to trigger cell damage—at least in the laboratory. In other words, cells seem more sensitive to iron than we previously thought.”

“This is very early stage research, and we need more work to confirm these findings and investigate what effects this may have on the body. We are still not sure how these laboratory findings translate to blood vessels in the body.”

“However, this study helps to open the conversation about how much iron people take. At the moment, each standard iron tablet contains almost 10 times the amount of iron men are recommended to eat each day, and these dosages haven’t changed for more than 50 years. This research suggests we may need to think more carefully about how much iron we give to people, and try and tailor the dose to the patient.”

Dr Shovlin and her colleagues initially started researching this area after finding that a small proportion of people using iron tablets for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which causes abnormalities in the blood vessels, reported their nose bleeds worsened after iron treatment. ![]()

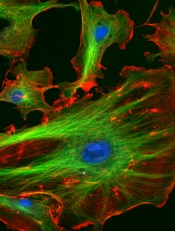

Image courtesy of NIH

Low doses of iron can modify the vascular endothelium and induce a DNA-damage response, researchers have reported in PLOS ONE.

The team observed these phenomena in vitro and said the results must be confirmed via additional research.

However, the findings suggest a need to assess the amount of iron given in standard treatments and the effects this may have on the body, according to Claire Shovlin, PhD, of Imperial College London in the UK.

Dr Shovlin and her colleagues studied human endothelial cells, adding either placebo or an iron solution of 10 micromolar, which is a similar concentration to that seen in the blood after taking an iron tablet.

Within 10 minutes, cells treated with the iron solution had activated DNA repair systems, and these were still activated 6 hours later.

“We already knew that iron could be damaging to cells in very high doses,” Dr Shovlin said. “However, in this study, we found that when we applied the kinds of levels of iron you would find in the bloodstream after taking an iron tablet, this also seemed to be able to trigger cell damage—at least in the laboratory. In other words, cells seem more sensitive to iron than we previously thought.”

“This is very early stage research, and we need more work to confirm these findings and investigate what effects this may have on the body. We are still not sure how these laboratory findings translate to blood vessels in the body.”

“However, this study helps to open the conversation about how much iron people take. At the moment, each standard iron tablet contains almost 10 times the amount of iron men are recommended to eat each day, and these dosages haven’t changed for more than 50 years. This research suggests we may need to think more carefully about how much iron we give to people, and try and tailor the dose to the patient.”

Dr Shovlin and her colleagues initially started researching this area after finding that a small proportion of people using iron tablets for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which causes abnormalities in the blood vessels, reported their nose bleeds worsened after iron treatment. ![]()