User login

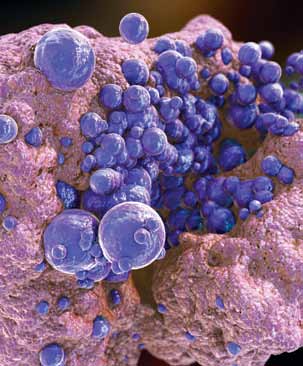

Case 1: Follow-up in Community-Acquired Methicillin- Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Pharyngitis

A 73-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of injuries she sustained following a minor fall at home. The patient’s past medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, and a history of chronic pain. During the course of evaluation, the patient mentioned that she had experienced a sore throat. In addition to X-rays, the emergency physician (EP) ordered a rapid strep test (RST). All studies were normal and the patient was discharged home.

Over the next 2 months, the patient received medical treatment from other medical professionals, but not at the previous hospital. Reportedly, she did not complain of a sore throat during this time period. The patient did return to the same ED approximately 2 months later, complaining of cough and difficulty breathing; she died 5 days thereafter. No autopsy was performed.

A lawsuit was filed on behalf of the patient, stating the hospital breached the standard of care by not reporting the finding of MRSA directly to the treating physician, and that this led directly to the patient’s death by MRSA pneumonia. The jury returned a verdict in favor of the plaintiff for $32 million.

Discussion

This case illustrates two simple but important points: managing community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) infections is a growing challenge for physicians; and hospital follow-up systems for positive findings (ie, fractures, blood cultures, etc) need to be consistently reliable.

It is estimated that 30% of healthy people carry S aureus in their anterior nares; colonization rates for the throat are much less studied. In one recent study, 265 throat swabs were collected from patients aged 14 to 65 years old, who complained of pharyngitis in an outpatient setting.1 A total of 165 S aureus isolates (62.3%) were recovered from the 265 swabs. For the S aureus isolates, 38.2% (63) grew CA-MRSA; the remaining 68.1% (102) were methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA). Interestingly, of the 63 MRSA-positive swabs, over half also grew Group A Streptococcus. The natural disease progression of CA-MRSA pharyngitis is still unknown, as is what to do with a positive throat swab for CA-MRSA. While there are a few case reports of bacteremia and Lemmiere syndrome possibly related to CA-MRSA pharyngitis,2,3 more information is clearly needed. For this case, it is not possible to definitively determine the role of the positive throat swab for CAMRSA in the patient’s subsequent death.

The other teaching point in this case is much simpler and well defined. Simply put, patients expect to be informed of positive findings, whether the result is known at the time of their ED visit or sometime afterward. There needs to be a system in place that consistently and reliably provides important information to either the patient’s treating physician or to the patient. The manners in which this information is communicated are myriad and should take into account hospital resources, the role of the EP and nurse, and what works best for your locality. The “who” and “how” of the contact is not important: reliability, timeliness, and consistency need to be the key drivers of the system.

Case 2: Arterial Occlusion

A 61-year-old woman called emergency medical services (EMS) after noticing her feet felt cold to the touch and having difficulty ambulating. The paramedics noted the patient had normal vital signs and normal circulation in her legs, and she was transported to the ED without incident. Upon arrival to the ED, she was triaged as nonurgent and placed in the minor-care area. On nursing assessment, the patient’s feet were found to be cold, but with palpable pulses bilaterally. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and DM.

The patient was seen by a physician assistant (PA), who found both feet cool to the touch, but with bilateral pulses present. She was administered intravenous morphine for pain and laboratory studies were ordered. At the time, the PA was concerned about arterial occlusion versus deep vein thrombosis (DVT) versus cellulitis. A venous ultrasound examination was ordered and shown to be negative for DVT. A complete blood count was remarkable only for mild leukocytosis. The PA discussed the case with the supervising EP; they agreed on a diagnosis of cellulitis and discharged the patient home with antibiotics and analgesics.

Approximately 12 hours after discharge, the patient presented back to the ED via ambulance. At that time, she was hypotensive and tachypneic, with a thready palpable pulse. On repeat examination, she no longer had pulses present in her feet. An arteriogram found complete occlusion of her arterial circulation at the level of the knees bilaterally, requiring bilateral belowthe- knee amputation.

The patient sued both the emergency medicine physician and the PA for failure to provide her with the necessary care during her initial ED visit, resulting in loss of limbs. The defendants claimed the patient could not prove gross negligence by clear and convincing evidence, as required by state law. Following the ensuing trial, the jury returned a $5 million verdict in favor of the plaintiff.

Discussion

First, it is important to remember that just because a patient has been triaged to a low-acuity area does not mean she or he must have a minor problem. The provider still must maintain a high level of vigilance— regardless of the location of the patient in the ED.

Second, was this patient in atrial fibrillation, which is responsible in approximately 65% of all peripheral emboli? The abrupt onset of this patient’s symptoms is much more compatible with an embolic origin of her symptoms rather than a thrombus (ie, symptoms of claudication).

Lastly, a diagnosis of cellulitis is inconsistent with the physical findings of the PA, as well as those of the triage nurse and paramedics. This patient’s feet were cool to the touch whereas cellulitis presents with erythema and increased warmth. While the presence of pulses was somewhat reassuring, the cool temperature of the feet and complaint of pain were indicators of the need to evaluate for a possible arterial origin of these findings. However, if this were an embolic phenomenon, peripheral arterial ultrasound would have probably been normal, and the outcome unchanged.

Case 3: Failure to Communicate

A 59-year-old man presented to his primary care physician (PCP) for intermittent right-hand weakness and numbness and tingling in his right arm during the previous 24 hours. As the PCP was concerned that the patient might be experiencing a transient ischemic attack (TIA), the patient and his wife were instructed to go directly to the ED of the local hospital. The PCP wrote a note stating that the patient needed “a stroke work up,” gave the note to the patient, and told him to give it to the ED staff.

The patient went directly to the ED and was immediately seen by a “rapid triage nurse.” He gave the note to the nurse and told her of the PCP’s concerns. The nurse documented on the hospital assessment form that the patient was high priority and needed to be seen immediately. She attached the PCP’s note to the front of the form.

The patient was then seen by the traditional triage nurse. After evaluation, she changed the priority from high to low acuity. The triage nurse later stated later that she never saw the PCP’s note, nor did she obtain any history regarding the concerns of the PCP.

The patient was then evaluated by an EP in the low-acuity (or minor-care) area of the ED. The EP later stated that he never saw the note from the PCP, and had not received any information regarding a suspected TIA or stroke. The EP ordered a right wrist X-ray, diagnosed carpel tunnel syndrome, and prescribed an anti-inflammatory medication as well as follow-up with a hand surgeon.

The initial (rapid triage) nurse saw the patient leaving the ED at the time of discharge and thought he had not been in the ED long enough to have undergone a stroke work up. She reviewed his paperwork and saw the patient had not received the indicated work up. The nurse called the patient’s house and left a message on the answering machine notifying him of the need to return to the ED. The patient arrived back to the ED approximately 2 hours later.

On the second ED presentation that day, the patient was evaluated by a different EP. The patient had blood drawn, an electrocardiogram, and a noncontrast computed tomography scan of the brain, the results of which were all normal. The EP concluded the patient required admission to the hospital for additional work up (eg, carotid Doppler ultrasound). The hospitalist was paged, and told the EP he would be there “as soon as possible.” However, after several hours delay, and no hospitalist, the patient became impatient and expressed the desire to go home. The EP urged the patient to follow up with his PCP in the morning to complete the evaluation.

The next day, before seeing his PCP, the patient suffered an ischemic stroke with right-sided hemiparesis. The case went to trial, and the jury found in favor of the plaintiff.

Discussion

Unfortunately, multiple opportunities were lost in obtaining the correct care at the right time for this patient. Lack of communication and poor communication are frequently cited as causes in medical malpractice cases, and this case perfectly illustrates this problem.

First, the PCP should have called the ED and spoken to the EP directly. This would have provided the PCP the opportunity to express his concerns directly to the treating physician. This kind of one-on-one communication between physicians will always be superior to a hand-written note.

Second, it is unclear why the triage nurse changed the initial nurse’s correct assessment. It is also unclear what happened to the PCP’s note—it was never seen again. Clearly there was miscommunication at this point between the triage nurse and the patient. This case further illustrates the importance of good triage. Once a patient is directed down the wrong pathway (ie, to minor care rather than the main treatment area), the situation becomes much more difficult to correct.

Next, the EP in the low-acuity area was probably falsely assured this patient had only a “minor” problem problem, and not something serious. Emergency physicians must be vigilant to the possibility that the patient can have something seriously wrong even if he or she has been triaged to a low-acuity area. A minor sore throat can turn out to be epiglottitis and a viral stomachache can turn out to be appendicitis. These patients deserve the same quality of history, physical examination, and differential diagnosis as any other patient in the ED.

Finally, while we are not responsible for hospitalists or consultants, we do have a responsibility to our patients. We need to ensure that the care they receive is the appropriate care. Possible alternatives to discharging this patient would have been to call another hospitalist for admission or to seek the input of the chief of the medical staff or the on-call hospital administrator. As EPs, we are frequently required to serve as the primary advocate for our patients.

There is the possibility that even if the patient had been admitted to the hospital, the outcome would have been the same. However, since he might have been a candidate for tissue plasminogen activator or interventional radiology if he had suffered the cerebrovascular accident as an inpatient, he lost his best chance for a good outcome.

- Gowrishankar S, Thenmozhi R, Balaji K, Pandian SK. Emergence of methicillin-resistant, vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus among patients associated with group A Streptococcal pharyngitis infection in southern India. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;14:383-389.

- Wang LJ, Du XQ, Nyirimigabo E, Shou ST. A case report: concurrent infectious mononucleosis and community-associated methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am J Emerg Med. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.10.033

- Kizhner VZ, Samara GJ, Panesar R, Krespi YP. MRSA bacteremia associated with Lemierre syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(suppl 2):P152,P153.

Case 1: Follow-up in Community-Acquired Methicillin- Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Pharyngitis

A 73-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of injuries she sustained following a minor fall at home. The patient’s past medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, and a history of chronic pain. During the course of evaluation, the patient mentioned that she had experienced a sore throat. In addition to X-rays, the emergency physician (EP) ordered a rapid strep test (RST). All studies were normal and the patient was discharged home.

Over the next 2 months, the patient received medical treatment from other medical professionals, but not at the previous hospital. Reportedly, she did not complain of a sore throat during this time period. The patient did return to the same ED approximately 2 months later, complaining of cough and difficulty breathing; she died 5 days thereafter. No autopsy was performed.

A lawsuit was filed on behalf of the patient, stating the hospital breached the standard of care by not reporting the finding of MRSA directly to the treating physician, and that this led directly to the patient’s death by MRSA pneumonia. The jury returned a verdict in favor of the plaintiff for $32 million.

Discussion

This case illustrates two simple but important points: managing community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) infections is a growing challenge for physicians; and hospital follow-up systems for positive findings (ie, fractures, blood cultures, etc) need to be consistently reliable.

It is estimated that 30% of healthy people carry S aureus in their anterior nares; colonization rates for the throat are much less studied. In one recent study, 265 throat swabs were collected from patients aged 14 to 65 years old, who complained of pharyngitis in an outpatient setting.1 A total of 165 S aureus isolates (62.3%) were recovered from the 265 swabs. For the S aureus isolates, 38.2% (63) grew CA-MRSA; the remaining 68.1% (102) were methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA). Interestingly, of the 63 MRSA-positive swabs, over half also grew Group A Streptococcus. The natural disease progression of CA-MRSA pharyngitis is still unknown, as is what to do with a positive throat swab for CA-MRSA. While there are a few case reports of bacteremia and Lemmiere syndrome possibly related to CA-MRSA pharyngitis,2,3 more information is clearly needed. For this case, it is not possible to definitively determine the role of the positive throat swab for CAMRSA in the patient’s subsequent death.

The other teaching point in this case is much simpler and well defined. Simply put, patients expect to be informed of positive findings, whether the result is known at the time of their ED visit or sometime afterward. There needs to be a system in place that consistently and reliably provides important information to either the patient’s treating physician or to the patient. The manners in which this information is communicated are myriad and should take into account hospital resources, the role of the EP and nurse, and what works best for your locality. The “who” and “how” of the contact is not important: reliability, timeliness, and consistency need to be the key drivers of the system.

Case 2: Arterial Occlusion

A 61-year-old woman called emergency medical services (EMS) after noticing her feet felt cold to the touch and having difficulty ambulating. The paramedics noted the patient had normal vital signs and normal circulation in her legs, and she was transported to the ED without incident. Upon arrival to the ED, she was triaged as nonurgent and placed in the minor-care area. On nursing assessment, the patient’s feet were found to be cold, but with palpable pulses bilaterally. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and DM.

The patient was seen by a physician assistant (PA), who found both feet cool to the touch, but with bilateral pulses present. She was administered intravenous morphine for pain and laboratory studies were ordered. At the time, the PA was concerned about arterial occlusion versus deep vein thrombosis (DVT) versus cellulitis. A venous ultrasound examination was ordered and shown to be negative for DVT. A complete blood count was remarkable only for mild leukocytosis. The PA discussed the case with the supervising EP; they agreed on a diagnosis of cellulitis and discharged the patient home with antibiotics and analgesics.

Approximately 12 hours after discharge, the patient presented back to the ED via ambulance. At that time, she was hypotensive and tachypneic, with a thready palpable pulse. On repeat examination, she no longer had pulses present in her feet. An arteriogram found complete occlusion of her arterial circulation at the level of the knees bilaterally, requiring bilateral belowthe- knee amputation.

The patient sued both the emergency medicine physician and the PA for failure to provide her with the necessary care during her initial ED visit, resulting in loss of limbs. The defendants claimed the patient could not prove gross negligence by clear and convincing evidence, as required by state law. Following the ensuing trial, the jury returned a $5 million verdict in favor of the plaintiff.

Discussion

First, it is important to remember that just because a patient has been triaged to a low-acuity area does not mean she or he must have a minor problem. The provider still must maintain a high level of vigilance— regardless of the location of the patient in the ED.

Second, was this patient in atrial fibrillation, which is responsible in approximately 65% of all peripheral emboli? The abrupt onset of this patient’s symptoms is much more compatible with an embolic origin of her symptoms rather than a thrombus (ie, symptoms of claudication).

Lastly, a diagnosis of cellulitis is inconsistent with the physical findings of the PA, as well as those of the triage nurse and paramedics. This patient’s feet were cool to the touch whereas cellulitis presents with erythema and increased warmth. While the presence of pulses was somewhat reassuring, the cool temperature of the feet and complaint of pain were indicators of the need to evaluate for a possible arterial origin of these findings. However, if this were an embolic phenomenon, peripheral arterial ultrasound would have probably been normal, and the outcome unchanged.

Case 3: Failure to Communicate

A 59-year-old man presented to his primary care physician (PCP) for intermittent right-hand weakness and numbness and tingling in his right arm during the previous 24 hours. As the PCP was concerned that the patient might be experiencing a transient ischemic attack (TIA), the patient and his wife were instructed to go directly to the ED of the local hospital. The PCP wrote a note stating that the patient needed “a stroke work up,” gave the note to the patient, and told him to give it to the ED staff.

The patient went directly to the ED and was immediately seen by a “rapid triage nurse.” He gave the note to the nurse and told her of the PCP’s concerns. The nurse documented on the hospital assessment form that the patient was high priority and needed to be seen immediately. She attached the PCP’s note to the front of the form.

The patient was then seen by the traditional triage nurse. After evaluation, she changed the priority from high to low acuity. The triage nurse later stated later that she never saw the PCP’s note, nor did she obtain any history regarding the concerns of the PCP.

The patient was then evaluated by an EP in the low-acuity (or minor-care) area of the ED. The EP later stated that he never saw the note from the PCP, and had not received any information regarding a suspected TIA or stroke. The EP ordered a right wrist X-ray, diagnosed carpel tunnel syndrome, and prescribed an anti-inflammatory medication as well as follow-up with a hand surgeon.

The initial (rapid triage) nurse saw the patient leaving the ED at the time of discharge and thought he had not been in the ED long enough to have undergone a stroke work up. She reviewed his paperwork and saw the patient had not received the indicated work up. The nurse called the patient’s house and left a message on the answering machine notifying him of the need to return to the ED. The patient arrived back to the ED approximately 2 hours later.

On the second ED presentation that day, the patient was evaluated by a different EP. The patient had blood drawn, an electrocardiogram, and a noncontrast computed tomography scan of the brain, the results of which were all normal. The EP concluded the patient required admission to the hospital for additional work up (eg, carotid Doppler ultrasound). The hospitalist was paged, and told the EP he would be there “as soon as possible.” However, after several hours delay, and no hospitalist, the patient became impatient and expressed the desire to go home. The EP urged the patient to follow up with his PCP in the morning to complete the evaluation.

The next day, before seeing his PCP, the patient suffered an ischemic stroke with right-sided hemiparesis. The case went to trial, and the jury found in favor of the plaintiff.

Discussion

Unfortunately, multiple opportunities were lost in obtaining the correct care at the right time for this patient. Lack of communication and poor communication are frequently cited as causes in medical malpractice cases, and this case perfectly illustrates this problem.

First, the PCP should have called the ED and spoken to the EP directly. This would have provided the PCP the opportunity to express his concerns directly to the treating physician. This kind of one-on-one communication between physicians will always be superior to a hand-written note.

Second, it is unclear why the triage nurse changed the initial nurse’s correct assessment. It is also unclear what happened to the PCP’s note—it was never seen again. Clearly there was miscommunication at this point between the triage nurse and the patient. This case further illustrates the importance of good triage. Once a patient is directed down the wrong pathway (ie, to minor care rather than the main treatment area), the situation becomes much more difficult to correct.

Next, the EP in the low-acuity area was probably falsely assured this patient had only a “minor” problem problem, and not something serious. Emergency physicians must be vigilant to the possibility that the patient can have something seriously wrong even if he or she has been triaged to a low-acuity area. A minor sore throat can turn out to be epiglottitis and a viral stomachache can turn out to be appendicitis. These patients deserve the same quality of history, physical examination, and differential diagnosis as any other patient in the ED.

Finally, while we are not responsible for hospitalists or consultants, we do have a responsibility to our patients. We need to ensure that the care they receive is the appropriate care. Possible alternatives to discharging this patient would have been to call another hospitalist for admission or to seek the input of the chief of the medical staff or the on-call hospital administrator. As EPs, we are frequently required to serve as the primary advocate for our patients.

There is the possibility that even if the patient had been admitted to the hospital, the outcome would have been the same. However, since he might have been a candidate for tissue plasminogen activator or interventional radiology if he had suffered the cerebrovascular accident as an inpatient, he lost his best chance for a good outcome.

Case 1: Follow-up in Community-Acquired Methicillin- Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Pharyngitis

A 73-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of injuries she sustained following a minor fall at home. The patient’s past medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, and a history of chronic pain. During the course of evaluation, the patient mentioned that she had experienced a sore throat. In addition to X-rays, the emergency physician (EP) ordered a rapid strep test (RST). All studies were normal and the patient was discharged home.

Over the next 2 months, the patient received medical treatment from other medical professionals, but not at the previous hospital. Reportedly, she did not complain of a sore throat during this time period. The patient did return to the same ED approximately 2 months later, complaining of cough and difficulty breathing; she died 5 days thereafter. No autopsy was performed.

A lawsuit was filed on behalf of the patient, stating the hospital breached the standard of care by not reporting the finding of MRSA directly to the treating physician, and that this led directly to the patient’s death by MRSA pneumonia. The jury returned a verdict in favor of the plaintiff for $32 million.

Discussion

This case illustrates two simple but important points: managing community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) infections is a growing challenge for physicians; and hospital follow-up systems for positive findings (ie, fractures, blood cultures, etc) need to be consistently reliable.

It is estimated that 30% of healthy people carry S aureus in their anterior nares; colonization rates for the throat are much less studied. In one recent study, 265 throat swabs were collected from patients aged 14 to 65 years old, who complained of pharyngitis in an outpatient setting.1 A total of 165 S aureus isolates (62.3%) were recovered from the 265 swabs. For the S aureus isolates, 38.2% (63) grew CA-MRSA; the remaining 68.1% (102) were methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA). Interestingly, of the 63 MRSA-positive swabs, over half also grew Group A Streptococcus. The natural disease progression of CA-MRSA pharyngitis is still unknown, as is what to do with a positive throat swab for CA-MRSA. While there are a few case reports of bacteremia and Lemmiere syndrome possibly related to CA-MRSA pharyngitis,2,3 more information is clearly needed. For this case, it is not possible to definitively determine the role of the positive throat swab for CAMRSA in the patient’s subsequent death.

The other teaching point in this case is much simpler and well defined. Simply put, patients expect to be informed of positive findings, whether the result is known at the time of their ED visit or sometime afterward. There needs to be a system in place that consistently and reliably provides important information to either the patient’s treating physician or to the patient. The manners in which this information is communicated are myriad and should take into account hospital resources, the role of the EP and nurse, and what works best for your locality. The “who” and “how” of the contact is not important: reliability, timeliness, and consistency need to be the key drivers of the system.

Case 2: Arterial Occlusion

A 61-year-old woman called emergency medical services (EMS) after noticing her feet felt cold to the touch and having difficulty ambulating. The paramedics noted the patient had normal vital signs and normal circulation in her legs, and she was transported to the ED without incident. Upon arrival to the ED, she was triaged as nonurgent and placed in the minor-care area. On nursing assessment, the patient’s feet were found to be cold, but with palpable pulses bilaterally. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and DM.

The patient was seen by a physician assistant (PA), who found both feet cool to the touch, but with bilateral pulses present. She was administered intravenous morphine for pain and laboratory studies were ordered. At the time, the PA was concerned about arterial occlusion versus deep vein thrombosis (DVT) versus cellulitis. A venous ultrasound examination was ordered and shown to be negative for DVT. A complete blood count was remarkable only for mild leukocytosis. The PA discussed the case with the supervising EP; they agreed on a diagnosis of cellulitis and discharged the patient home with antibiotics and analgesics.

Approximately 12 hours after discharge, the patient presented back to the ED via ambulance. At that time, she was hypotensive and tachypneic, with a thready palpable pulse. On repeat examination, she no longer had pulses present in her feet. An arteriogram found complete occlusion of her arterial circulation at the level of the knees bilaterally, requiring bilateral belowthe- knee amputation.

The patient sued both the emergency medicine physician and the PA for failure to provide her with the necessary care during her initial ED visit, resulting in loss of limbs. The defendants claimed the patient could not prove gross negligence by clear and convincing evidence, as required by state law. Following the ensuing trial, the jury returned a $5 million verdict in favor of the plaintiff.

Discussion

First, it is important to remember that just because a patient has been triaged to a low-acuity area does not mean she or he must have a minor problem. The provider still must maintain a high level of vigilance— regardless of the location of the patient in the ED.

Second, was this patient in atrial fibrillation, which is responsible in approximately 65% of all peripheral emboli? The abrupt onset of this patient’s symptoms is much more compatible with an embolic origin of her symptoms rather than a thrombus (ie, symptoms of claudication).

Lastly, a diagnosis of cellulitis is inconsistent with the physical findings of the PA, as well as those of the triage nurse and paramedics. This patient’s feet were cool to the touch whereas cellulitis presents with erythema and increased warmth. While the presence of pulses was somewhat reassuring, the cool temperature of the feet and complaint of pain were indicators of the need to evaluate for a possible arterial origin of these findings. However, if this were an embolic phenomenon, peripheral arterial ultrasound would have probably been normal, and the outcome unchanged.

Case 3: Failure to Communicate

A 59-year-old man presented to his primary care physician (PCP) for intermittent right-hand weakness and numbness and tingling in his right arm during the previous 24 hours. As the PCP was concerned that the patient might be experiencing a transient ischemic attack (TIA), the patient and his wife were instructed to go directly to the ED of the local hospital. The PCP wrote a note stating that the patient needed “a stroke work up,” gave the note to the patient, and told him to give it to the ED staff.

The patient went directly to the ED and was immediately seen by a “rapid triage nurse.” He gave the note to the nurse and told her of the PCP’s concerns. The nurse documented on the hospital assessment form that the patient was high priority and needed to be seen immediately. She attached the PCP’s note to the front of the form.

The patient was then seen by the traditional triage nurse. After evaluation, she changed the priority from high to low acuity. The triage nurse later stated later that she never saw the PCP’s note, nor did she obtain any history regarding the concerns of the PCP.

The patient was then evaluated by an EP in the low-acuity (or minor-care) area of the ED. The EP later stated that he never saw the note from the PCP, and had not received any information regarding a suspected TIA or stroke. The EP ordered a right wrist X-ray, diagnosed carpel tunnel syndrome, and prescribed an anti-inflammatory medication as well as follow-up with a hand surgeon.

The initial (rapid triage) nurse saw the patient leaving the ED at the time of discharge and thought he had not been in the ED long enough to have undergone a stroke work up. She reviewed his paperwork and saw the patient had not received the indicated work up. The nurse called the patient’s house and left a message on the answering machine notifying him of the need to return to the ED. The patient arrived back to the ED approximately 2 hours later.

On the second ED presentation that day, the patient was evaluated by a different EP. The patient had blood drawn, an electrocardiogram, and a noncontrast computed tomography scan of the brain, the results of which were all normal. The EP concluded the patient required admission to the hospital for additional work up (eg, carotid Doppler ultrasound). The hospitalist was paged, and told the EP he would be there “as soon as possible.” However, after several hours delay, and no hospitalist, the patient became impatient and expressed the desire to go home. The EP urged the patient to follow up with his PCP in the morning to complete the evaluation.

The next day, before seeing his PCP, the patient suffered an ischemic stroke with right-sided hemiparesis. The case went to trial, and the jury found in favor of the plaintiff.

Discussion

Unfortunately, multiple opportunities were lost in obtaining the correct care at the right time for this patient. Lack of communication and poor communication are frequently cited as causes in medical malpractice cases, and this case perfectly illustrates this problem.

First, the PCP should have called the ED and spoken to the EP directly. This would have provided the PCP the opportunity to express his concerns directly to the treating physician. This kind of one-on-one communication between physicians will always be superior to a hand-written note.

Second, it is unclear why the triage nurse changed the initial nurse’s correct assessment. It is also unclear what happened to the PCP’s note—it was never seen again. Clearly there was miscommunication at this point between the triage nurse and the patient. This case further illustrates the importance of good triage. Once a patient is directed down the wrong pathway (ie, to minor care rather than the main treatment area), the situation becomes much more difficult to correct.

Next, the EP in the low-acuity area was probably falsely assured this patient had only a “minor” problem problem, and not something serious. Emergency physicians must be vigilant to the possibility that the patient can have something seriously wrong even if he or she has been triaged to a low-acuity area. A minor sore throat can turn out to be epiglottitis and a viral stomachache can turn out to be appendicitis. These patients deserve the same quality of history, physical examination, and differential diagnosis as any other patient in the ED.

Finally, while we are not responsible for hospitalists or consultants, we do have a responsibility to our patients. We need to ensure that the care they receive is the appropriate care. Possible alternatives to discharging this patient would have been to call another hospitalist for admission or to seek the input of the chief of the medical staff or the on-call hospital administrator. As EPs, we are frequently required to serve as the primary advocate for our patients.

There is the possibility that even if the patient had been admitted to the hospital, the outcome would have been the same. However, since he might have been a candidate for tissue plasminogen activator or interventional radiology if he had suffered the cerebrovascular accident as an inpatient, he lost his best chance for a good outcome.

- Gowrishankar S, Thenmozhi R, Balaji K, Pandian SK. Emergence of methicillin-resistant, vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus among patients associated with group A Streptococcal pharyngitis infection in southern India. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;14:383-389.

- Wang LJ, Du XQ, Nyirimigabo E, Shou ST. A case report: concurrent infectious mononucleosis and community-associated methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am J Emerg Med. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.10.033

- Kizhner VZ, Samara GJ, Panesar R, Krespi YP. MRSA bacteremia associated with Lemierre syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(suppl 2):P152,P153.

- Gowrishankar S, Thenmozhi R, Balaji K, Pandian SK. Emergence of methicillin-resistant, vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus among patients associated with group A Streptococcal pharyngitis infection in southern India. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;14:383-389.

- Wang LJ, Du XQ, Nyirimigabo E, Shou ST. A case report: concurrent infectious mononucleosis and community-associated methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am J Emerg Med. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.10.033

- Kizhner VZ, Samara GJ, Panesar R, Krespi YP. MRSA bacteremia associated with Lemierre syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(suppl 2):P152,P153.