User login

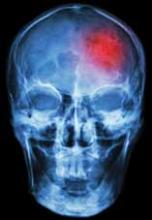

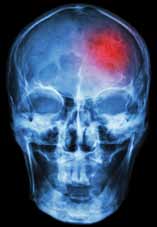

Stroke in a Young Man

A 26-year-old man presented to the ED with the chief complaint of mild right-sided weakness, paresthesias, and slurred speech. He stated the onset was sudden—approximately 30 minutes prior to arrival to the ED. The patient denied any previous similar symptoms and was otherwise in good health; he denied taking any medications. He drank alcohol socially, but denied smoking or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, his vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal. Pulmonary, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations were also normal. The patient thought his speech was somewhat slurred, but the triage nurse and treating emergency physician (EP) had difficulty detecting any altered speech. He was noted to have mild (4+/5) right upper and lower extremity weakness; no facial droop was detected. The patient did have a mild pronator drift of the right upper extremity. Gait testing revealed a mild limp of the right lower extremity.

The EP consulted the hospitalist, and the patient was admitted to a monitored bed. The following morning, a brain magnetic resonance image revealed an ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery. The patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated, but at the time of discharge, he continued to have mild right-sided weakness and required the use of a cane.

The patient sued the hospital and the EP for negligence in failing to treat his condition in a timely manner and for not consulting a neurologist. The plaintiff’s attorneys argued the patient should have been given tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which would have avoided the residual right-sided weakness. The defense denied negligence and argued the patient’s symptoms could have been due to several things for which tPA would have been an inappropriate treatment. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Stroke in young patients is relatively rare. With “young” defined as aged 18 to 45 years, this population accounts for approximately 2% to 12% of cerebral infarcts.1 In one nationwide US study of stroke in young adults, Ellis2 found that 4.9% of individuals experiencing a stroke in 2007 were between ages 18 and 44 years. Among this group, 78% experienced an ischemic stroke; 11.2% experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); and 10.8% had an intracerebral hemorrhage.2

While the clinical presentation of stroke in young adults is similar to that of older patients, the etiologies and risk factors are very different. In older patients, atherosclerosis is the major cause of ischemic stroke. In studies of young adults with ischemic stroke, cardioembolism was found to be the leading cause. Under this category, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) was considered a common cause, followed by atrial fibrillation, bacterial endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, and atrial myxoma. There is, however, increasing controversy over the role of PFO as an etiology of stroke. Many investigators think its role has been overstated and is probably more of an incidental finding than a causal relationship.3 Patients with a suspected cardioembolic etiology will usually require an echocardiogram (with saline contrast or a “bubble study” for suspected PFO), cardiac monitoring, and a possible Holter monitor at the time of discharge (to detect paroxysmal arrhythmias).

Following cardioembolic etiologies, arterial dissection is the next most common category.4 In one study of patients aged 31 to 45 years old, arterial dissection was the most common cause of ischemic stroke.4 Clinical features suggesting dissection include a history of head or neck trauma (even minor trauma), headache or neck pain, and local neurological findings (eg, cranial nerve palsy or Horner syndrome).3 Unfortunately, only about 25% of patients volunteer a history of recent neck trauma. If a cervical or vertebral artery dissection is suspected, contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is the most sensitive and specific test, followed by carotid ultrasound and CT angiography.3

Traditional risk factors for stroke include hypertension and diabetes mellitus (DM). This is not true for younger adults that experience an ischemic stroke. Cigarette smoking is a very important risk factor for cerebrovascular accident in young adults; in addition, the more one smokes, the greater the risk. Other risk factors in young adults include history of migraine headaches (especially migraine with aura), pregnancy and the postpartum period, and illicit drug use.3

The defense’s argument that there are many causes of stroke in young adults that would be inappropriate for treatment with tPA, such as a PFO, carotid dissection or bacterial endocarditis, is absolutely true. Young patients need to be aggressively worked up for the etiology of their stroke, and may require additional testing, such as an MRA, echocardiogram, or Holter monitoring to determine the underlying cause of their stroke.

Obstruction Following Gastric Bypass Surgery

A 47-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of severe back and abdominal pain. Onset had been gradual and began approximately 4 hours prior to arrival. She described the pain as crampy and constant. The patient had vomited twice; she denied diarrhea and had a normal bowel movement the previous day. She denied any vaginal or urinary complaints. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and status post gastric bypass surgery 6 months prior. She had lost 42 pounds to date. She denied smoking or alcohol use.

The patient’s vital signs on physical examination were: blood pressure, 154/92 mm Hg; pulse, 106 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient’s lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. The heart was mildly tachycardic, with a regular rhythm and without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The abdominal examination revealed diffuse tenderness and involuntary guarding. There was no distention or rebound. Bowel sounds were present but hypoactive. Examination of the back revealed bilateral paraspinal muscle tenderness without costovertebral angle tenderness.

The EP ordered a CBC, BMP, serum lipase, and a urinalysis. The patient was given an intravenous (IV) bolus of 250 cc normal saline in addition to IV morphine 4 mg and IV ondansetron 4 mg. Her white blood cell (WBC) count was slightly elevated at 12.2 g/dL, with a normal differential. The remainder of the laboratory studies were normal, except for a serum bicarbonate of 22 mmol/L.

The patient stated she felt somewhat improved, but continued to have abdominal and back pain. The EP admitted her to the hospital for observation and pain control. She died the following day from a bowel obstruction. The family sued the EP for negligence in failing to order appropriate testing and for not consulting with specialists to diagnose the bowel obstruction, which is a known complication of gastric bypass surgery. The jury returned a verdict of $2.4 million against the EP.

Discussion

The frequency of bariatric surgery in the United States continues to increase, primarily due to its success with regard to weight loss, but also because of its demonstrated improvement in hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 DM.1

Frequently, the term “gastric bypass surgery” is used interchangeably with bariatric surgery. However, the EP must realize these terms encompass multiple different operations. The four most common types of bariatric surgery in the United Stated are (1) adjustable gastric banding (AGB); (2) the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); (3) biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS); and (4) vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG).2 (See the Table for a brief explanation of each type of procedure.)

Since each procedure has its own respective associated complications, it is important for the EP to know which the type of gastric bypass surgery the patient had. For example, leakage is much more frequent following RYGB than in gastric banding, while slippage and obstruction are the most common complications of gastric banding.3,4 It is also very helpful to know the specific type of procedure when discussing the case with the surgical consultant.

Based on a recent review of over 800,000 bariatric surgery patients, seven serious common complications following the surgery were identified.3 These included bleeding, leakage, obstruction, stomal ulceration, pulmonary embolism and respiratory complications, blood sugar disturbances (usually hypoglycemia and/or metabolic acidosis), and nutritional disturbances. While not all-inclusive, this list represents the most common serious complications of gastric bypass surgery.

The complaint of abdominal pain in a patient that has undergone bariatric surgery should be taken very seriously. In addition to determining the specific procedure performed and date, the patient should be questioned about vomiting, bowel movements, and the presence of blood in stool or vomit. Depending upon the degree of pain present, the patient may need to be given IV opioid analgesia to facilitate a thorough abdominal examination. A rectal examination should be performed to identify occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

These patients require laboratory testing, including CBC, BMP, and other laboratory evaluation as indicated by the history and physical examination. Early consultation with the bariatric surgeon is recommended. Many, if not most, patients with abdominal pain and vomiting will require imaging, usually a CT scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis. Because of the difficulty in interpreting the CT scan results in these patients, the bariatric surgeon will often want to personally review the films rather than rely solely on the interpretation by radiology services.

Unfortunately, the EP in this case did not appreciate the seriousness of the situation. The presence of severe abdominal pain, tenderness, guarding, mild tachycardia with leukocytosis, and metabolic acidosis all pointed to a more serious etiology than muscle spasm. This patient required IV fluids, analgesia, and imaging, as well as consultation with the bariatric surgeon.

- Chatzikonstantinou A, Wolf ME, Hennerici MG. Ischemic stroke in young adults: classification and risk factors. J Neurol. 2012;259(4):653-659.

- Ellis C. Stroke in young adults. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(3):222-224.

- Ferro JM, Massaro AR, Mas JL. Aetiological diagnosis of ischemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1085-1096.

- Chan MT, Nadareishvili ZG, Norris JW; Canadian Stroke Consortium. Diagnostic strategies in young patients with ischemic stroke in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(2):120-124.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724-1737.

- Livingston EH. Patient guide: Endocrine and nutritional management after bariatric surgery: A patient’s guide. Hormone Health Network Web site. http://www.hormone.org/~/media/Hormone/Files/Patient%20Guides/Mens%20Health/PGBariatricSurgery_2014.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2014.

- Hussain A, El-Hasani S. Bariatric emergencies: current evidence and strategies of management. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8(1):58.

- Campanille FC, Boru C, Rizzello M, et al. Acute complications after laparoscopic bariatric procedures: update for the general surgeon. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398(5):669-686

Stroke in a Young Man

A 26-year-old man presented to the ED with the chief complaint of mild right-sided weakness, paresthesias, and slurred speech. He stated the onset was sudden—approximately 30 minutes prior to arrival to the ED. The patient denied any previous similar symptoms and was otherwise in good health; he denied taking any medications. He drank alcohol socially, but denied smoking or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, his vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal. Pulmonary, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations were also normal. The patient thought his speech was somewhat slurred, but the triage nurse and treating emergency physician (EP) had difficulty detecting any altered speech. He was noted to have mild (4+/5) right upper and lower extremity weakness; no facial droop was detected. The patient did have a mild pronator drift of the right upper extremity. Gait testing revealed a mild limp of the right lower extremity.

The EP consulted the hospitalist, and the patient was admitted to a monitored bed. The following morning, a brain magnetic resonance image revealed an ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery. The patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated, but at the time of discharge, he continued to have mild right-sided weakness and required the use of a cane.

The patient sued the hospital and the EP for negligence in failing to treat his condition in a timely manner and for not consulting a neurologist. The plaintiff’s attorneys argued the patient should have been given tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which would have avoided the residual right-sided weakness. The defense denied negligence and argued the patient’s symptoms could have been due to several things for which tPA would have been an inappropriate treatment. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Stroke in young patients is relatively rare. With “young” defined as aged 18 to 45 years, this population accounts for approximately 2% to 12% of cerebral infarcts.1 In one nationwide US study of stroke in young adults, Ellis2 found that 4.9% of individuals experiencing a stroke in 2007 were between ages 18 and 44 years. Among this group, 78% experienced an ischemic stroke; 11.2% experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); and 10.8% had an intracerebral hemorrhage.2

While the clinical presentation of stroke in young adults is similar to that of older patients, the etiologies and risk factors are very different. In older patients, atherosclerosis is the major cause of ischemic stroke. In studies of young adults with ischemic stroke, cardioembolism was found to be the leading cause. Under this category, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) was considered a common cause, followed by atrial fibrillation, bacterial endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, and atrial myxoma. There is, however, increasing controversy over the role of PFO as an etiology of stroke. Many investigators think its role has been overstated and is probably more of an incidental finding than a causal relationship.3 Patients with a suspected cardioembolic etiology will usually require an echocardiogram (with saline contrast or a “bubble study” for suspected PFO), cardiac monitoring, and a possible Holter monitor at the time of discharge (to detect paroxysmal arrhythmias).

Following cardioembolic etiologies, arterial dissection is the next most common category.4 In one study of patients aged 31 to 45 years old, arterial dissection was the most common cause of ischemic stroke.4 Clinical features suggesting dissection include a history of head or neck trauma (even minor trauma), headache or neck pain, and local neurological findings (eg, cranial nerve palsy or Horner syndrome).3 Unfortunately, only about 25% of patients volunteer a history of recent neck trauma. If a cervical or vertebral artery dissection is suspected, contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is the most sensitive and specific test, followed by carotid ultrasound and CT angiography.3

Traditional risk factors for stroke include hypertension and diabetes mellitus (DM). This is not true for younger adults that experience an ischemic stroke. Cigarette smoking is a very important risk factor for cerebrovascular accident in young adults; in addition, the more one smokes, the greater the risk. Other risk factors in young adults include history of migraine headaches (especially migraine with aura), pregnancy and the postpartum period, and illicit drug use.3

The defense’s argument that there are many causes of stroke in young adults that would be inappropriate for treatment with tPA, such as a PFO, carotid dissection or bacterial endocarditis, is absolutely true. Young patients need to be aggressively worked up for the etiology of their stroke, and may require additional testing, such as an MRA, echocardiogram, or Holter monitoring to determine the underlying cause of their stroke.

Obstruction Following Gastric Bypass Surgery

A 47-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of severe back and abdominal pain. Onset had been gradual and began approximately 4 hours prior to arrival. She described the pain as crampy and constant. The patient had vomited twice; she denied diarrhea and had a normal bowel movement the previous day. She denied any vaginal or urinary complaints. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and status post gastric bypass surgery 6 months prior. She had lost 42 pounds to date. She denied smoking or alcohol use.

The patient’s vital signs on physical examination were: blood pressure, 154/92 mm Hg; pulse, 106 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient’s lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. The heart was mildly tachycardic, with a regular rhythm and without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The abdominal examination revealed diffuse tenderness and involuntary guarding. There was no distention or rebound. Bowel sounds were present but hypoactive. Examination of the back revealed bilateral paraspinal muscle tenderness without costovertebral angle tenderness.

The EP ordered a CBC, BMP, serum lipase, and a urinalysis. The patient was given an intravenous (IV) bolus of 250 cc normal saline in addition to IV morphine 4 mg and IV ondansetron 4 mg. Her white blood cell (WBC) count was slightly elevated at 12.2 g/dL, with a normal differential. The remainder of the laboratory studies were normal, except for a serum bicarbonate of 22 mmol/L.

The patient stated she felt somewhat improved, but continued to have abdominal and back pain. The EP admitted her to the hospital for observation and pain control. She died the following day from a bowel obstruction. The family sued the EP for negligence in failing to order appropriate testing and for not consulting with specialists to diagnose the bowel obstruction, which is a known complication of gastric bypass surgery. The jury returned a verdict of $2.4 million against the EP.

Discussion

The frequency of bariatric surgery in the United States continues to increase, primarily due to its success with regard to weight loss, but also because of its demonstrated improvement in hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 DM.1

Frequently, the term “gastric bypass surgery” is used interchangeably with bariatric surgery. However, the EP must realize these terms encompass multiple different operations. The four most common types of bariatric surgery in the United Stated are (1) adjustable gastric banding (AGB); (2) the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); (3) biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS); and (4) vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG).2 (See the Table for a brief explanation of each type of procedure.)

Since each procedure has its own respective associated complications, it is important for the EP to know which the type of gastric bypass surgery the patient had. For example, leakage is much more frequent following RYGB than in gastric banding, while slippage and obstruction are the most common complications of gastric banding.3,4 It is also very helpful to know the specific type of procedure when discussing the case with the surgical consultant.

Based on a recent review of over 800,000 bariatric surgery patients, seven serious common complications following the surgery were identified.3 These included bleeding, leakage, obstruction, stomal ulceration, pulmonary embolism and respiratory complications, blood sugar disturbances (usually hypoglycemia and/or metabolic acidosis), and nutritional disturbances. While not all-inclusive, this list represents the most common serious complications of gastric bypass surgery.

The complaint of abdominal pain in a patient that has undergone bariatric surgery should be taken very seriously. In addition to determining the specific procedure performed and date, the patient should be questioned about vomiting, bowel movements, and the presence of blood in stool or vomit. Depending upon the degree of pain present, the patient may need to be given IV opioid analgesia to facilitate a thorough abdominal examination. A rectal examination should be performed to identify occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

These patients require laboratory testing, including CBC, BMP, and other laboratory evaluation as indicated by the history and physical examination. Early consultation with the bariatric surgeon is recommended. Many, if not most, patients with abdominal pain and vomiting will require imaging, usually a CT scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis. Because of the difficulty in interpreting the CT scan results in these patients, the bariatric surgeon will often want to personally review the films rather than rely solely on the interpretation by radiology services.

Unfortunately, the EP in this case did not appreciate the seriousness of the situation. The presence of severe abdominal pain, tenderness, guarding, mild tachycardia with leukocytosis, and metabolic acidosis all pointed to a more serious etiology than muscle spasm. This patient required IV fluids, analgesia, and imaging, as well as consultation with the bariatric surgeon.

Stroke in a Young Man

A 26-year-old man presented to the ED with the chief complaint of mild right-sided weakness, paresthesias, and slurred speech. He stated the onset was sudden—approximately 30 minutes prior to arrival to the ED. The patient denied any previous similar symptoms and was otherwise in good health; he denied taking any medications. He drank alcohol socially, but denied smoking or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, his vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal. Pulmonary, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations were also normal. The patient thought his speech was somewhat slurred, but the triage nurse and treating emergency physician (EP) had difficulty detecting any altered speech. He was noted to have mild (4+/5) right upper and lower extremity weakness; no facial droop was detected. The patient did have a mild pronator drift of the right upper extremity. Gait testing revealed a mild limp of the right lower extremity.

The EP consulted the hospitalist, and the patient was admitted to a monitored bed. The following morning, a brain magnetic resonance image revealed an ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery. The patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated, but at the time of discharge, he continued to have mild right-sided weakness and required the use of a cane.

The patient sued the hospital and the EP for negligence in failing to treat his condition in a timely manner and for not consulting a neurologist. The plaintiff’s attorneys argued the patient should have been given tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which would have avoided the residual right-sided weakness. The defense denied negligence and argued the patient’s symptoms could have been due to several things for which tPA would have been an inappropriate treatment. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Stroke in young patients is relatively rare. With “young” defined as aged 18 to 45 years, this population accounts for approximately 2% to 12% of cerebral infarcts.1 In one nationwide US study of stroke in young adults, Ellis2 found that 4.9% of individuals experiencing a stroke in 2007 were between ages 18 and 44 years. Among this group, 78% experienced an ischemic stroke; 11.2% experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); and 10.8% had an intracerebral hemorrhage.2

While the clinical presentation of stroke in young adults is similar to that of older patients, the etiologies and risk factors are very different. In older patients, atherosclerosis is the major cause of ischemic stroke. In studies of young adults with ischemic stroke, cardioembolism was found to be the leading cause. Under this category, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) was considered a common cause, followed by atrial fibrillation, bacterial endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, and atrial myxoma. There is, however, increasing controversy over the role of PFO as an etiology of stroke. Many investigators think its role has been overstated and is probably more of an incidental finding than a causal relationship.3 Patients with a suspected cardioembolic etiology will usually require an echocardiogram (with saline contrast or a “bubble study” for suspected PFO), cardiac monitoring, and a possible Holter monitor at the time of discharge (to detect paroxysmal arrhythmias).

Following cardioembolic etiologies, arterial dissection is the next most common category.4 In one study of patients aged 31 to 45 years old, arterial dissection was the most common cause of ischemic stroke.4 Clinical features suggesting dissection include a history of head or neck trauma (even minor trauma), headache or neck pain, and local neurological findings (eg, cranial nerve palsy or Horner syndrome).3 Unfortunately, only about 25% of patients volunteer a history of recent neck trauma. If a cervical or vertebral artery dissection is suspected, contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is the most sensitive and specific test, followed by carotid ultrasound and CT angiography.3

Traditional risk factors for stroke include hypertension and diabetes mellitus (DM). This is not true for younger adults that experience an ischemic stroke. Cigarette smoking is a very important risk factor for cerebrovascular accident in young adults; in addition, the more one smokes, the greater the risk. Other risk factors in young adults include history of migraine headaches (especially migraine with aura), pregnancy and the postpartum period, and illicit drug use.3

The defense’s argument that there are many causes of stroke in young adults that would be inappropriate for treatment with tPA, such as a PFO, carotid dissection or bacterial endocarditis, is absolutely true. Young patients need to be aggressively worked up for the etiology of their stroke, and may require additional testing, such as an MRA, echocardiogram, or Holter monitoring to determine the underlying cause of their stroke.

Obstruction Following Gastric Bypass Surgery

A 47-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of severe back and abdominal pain. Onset had been gradual and began approximately 4 hours prior to arrival. She described the pain as crampy and constant. The patient had vomited twice; she denied diarrhea and had a normal bowel movement the previous day. She denied any vaginal or urinary complaints. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and status post gastric bypass surgery 6 months prior. She had lost 42 pounds to date. She denied smoking or alcohol use.

The patient’s vital signs on physical examination were: blood pressure, 154/92 mm Hg; pulse, 106 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient’s lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. The heart was mildly tachycardic, with a regular rhythm and without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The abdominal examination revealed diffuse tenderness and involuntary guarding. There was no distention or rebound. Bowel sounds were present but hypoactive. Examination of the back revealed bilateral paraspinal muscle tenderness without costovertebral angle tenderness.

The EP ordered a CBC, BMP, serum lipase, and a urinalysis. The patient was given an intravenous (IV) bolus of 250 cc normal saline in addition to IV morphine 4 mg and IV ondansetron 4 mg. Her white blood cell (WBC) count was slightly elevated at 12.2 g/dL, with a normal differential. The remainder of the laboratory studies were normal, except for a serum bicarbonate of 22 mmol/L.

The patient stated she felt somewhat improved, but continued to have abdominal and back pain. The EP admitted her to the hospital for observation and pain control. She died the following day from a bowel obstruction. The family sued the EP for negligence in failing to order appropriate testing and for not consulting with specialists to diagnose the bowel obstruction, which is a known complication of gastric bypass surgery. The jury returned a verdict of $2.4 million against the EP.

Discussion

The frequency of bariatric surgery in the United States continues to increase, primarily due to its success with regard to weight loss, but also because of its demonstrated improvement in hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 DM.1

Frequently, the term “gastric bypass surgery” is used interchangeably with bariatric surgery. However, the EP must realize these terms encompass multiple different operations. The four most common types of bariatric surgery in the United Stated are (1) adjustable gastric banding (AGB); (2) the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); (3) biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS); and (4) vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG).2 (See the Table for a brief explanation of each type of procedure.)

Since each procedure has its own respective associated complications, it is important for the EP to know which the type of gastric bypass surgery the patient had. For example, leakage is much more frequent following RYGB than in gastric banding, while slippage and obstruction are the most common complications of gastric banding.3,4 It is also very helpful to know the specific type of procedure when discussing the case with the surgical consultant.

Based on a recent review of over 800,000 bariatric surgery patients, seven serious common complications following the surgery were identified.3 These included bleeding, leakage, obstruction, stomal ulceration, pulmonary embolism and respiratory complications, blood sugar disturbances (usually hypoglycemia and/or metabolic acidosis), and nutritional disturbances. While not all-inclusive, this list represents the most common serious complications of gastric bypass surgery.

The complaint of abdominal pain in a patient that has undergone bariatric surgery should be taken very seriously. In addition to determining the specific procedure performed and date, the patient should be questioned about vomiting, bowel movements, and the presence of blood in stool or vomit. Depending upon the degree of pain present, the patient may need to be given IV opioid analgesia to facilitate a thorough abdominal examination. A rectal examination should be performed to identify occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

These patients require laboratory testing, including CBC, BMP, and other laboratory evaluation as indicated by the history and physical examination. Early consultation with the bariatric surgeon is recommended. Many, if not most, patients with abdominal pain and vomiting will require imaging, usually a CT scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis. Because of the difficulty in interpreting the CT scan results in these patients, the bariatric surgeon will often want to personally review the films rather than rely solely on the interpretation by radiology services.

Unfortunately, the EP in this case did not appreciate the seriousness of the situation. The presence of severe abdominal pain, tenderness, guarding, mild tachycardia with leukocytosis, and metabolic acidosis all pointed to a more serious etiology than muscle spasm. This patient required IV fluids, analgesia, and imaging, as well as consultation with the bariatric surgeon.

- Chatzikonstantinou A, Wolf ME, Hennerici MG. Ischemic stroke in young adults: classification and risk factors. J Neurol. 2012;259(4):653-659.

- Ellis C. Stroke in young adults. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(3):222-224.

- Ferro JM, Massaro AR, Mas JL. Aetiological diagnosis of ischemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1085-1096.

- Chan MT, Nadareishvili ZG, Norris JW; Canadian Stroke Consortium. Diagnostic strategies in young patients with ischemic stroke in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(2):120-124.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724-1737.

- Livingston EH. Patient guide: Endocrine and nutritional management after bariatric surgery: A patient’s guide. Hormone Health Network Web site. http://www.hormone.org/~/media/Hormone/Files/Patient%20Guides/Mens%20Health/PGBariatricSurgery_2014.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2014.

- Hussain A, El-Hasani S. Bariatric emergencies: current evidence and strategies of management. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8(1):58.

- Campanille FC, Boru C, Rizzello M, et al. Acute complications after laparoscopic bariatric procedures: update for the general surgeon. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398(5):669-686

- Chatzikonstantinou A, Wolf ME, Hennerici MG. Ischemic stroke in young adults: classification and risk factors. J Neurol. 2012;259(4):653-659.

- Ellis C. Stroke in young adults. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(3):222-224.

- Ferro JM, Massaro AR, Mas JL. Aetiological diagnosis of ischemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1085-1096.

- Chan MT, Nadareishvili ZG, Norris JW; Canadian Stroke Consortium. Diagnostic strategies in young patients with ischemic stroke in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(2):120-124.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724-1737.

- Livingston EH. Patient guide: Endocrine and nutritional management after bariatric surgery: A patient’s guide. Hormone Health Network Web site. http://www.hormone.org/~/media/Hormone/Files/Patient%20Guides/Mens%20Health/PGBariatricSurgery_2014.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2014.

- Hussain A, El-Hasani S. Bariatric emergencies: current evidence and strategies of management. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8(1):58.

- Campanille FC, Boru C, Rizzello M, et al. Acute complications after laparoscopic bariatric procedures: update for the general surgeon. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398(5):669-686