User login

I remember that day like it was yesterday, though it occurred more than a decade ago. I stood leaning over a black entertainment center in my family room, legs wobbly, heart weary – a surreal and solemn snapshot in time. From a speaker streamed a now-favorite Donnie McClurkin song, called "Stand," with its introspective lyrics: "You’ve prayed and you’ve cried ... . After you’ve done all you can, you just stand."

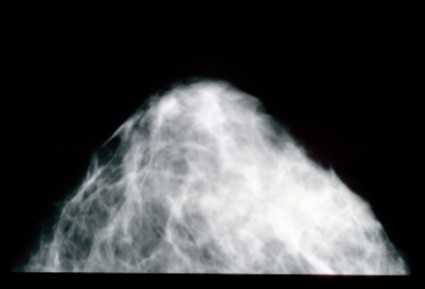

In the next room I could hear her softly gurgling on her secretions. I needed a moment, no, two or three moments, to collect my thoughts and pull myself together before I returned to face the nightmare I was living. My mother was actively dying in my guestroom. Why? I believed then and, today, many years later, believe just as strongly it was because she had not been getting her mammograms.

As a writer, sometimes I struggle with how personal to get in my blogs, but rest assured. I got her permission to share her story while she was still very lucid and competent. You see, she did not want others’ lives to end as hers was ending. She realized, in her final stages of life, that things would have likely been much different had she had her screening mammograms as recommended.

By the time of her diagnosis in her early 60s, the cancer had already spread. Would a mammogram in her late 50s have saved her life? I believe so, and I’m not alone. So I take issue with a recent article published in BMJ that downplays the significance of mammography (BMJ 2014;348:g366).

In 1980, Canadian researchers randomized 89,835 women, aged 40-59 to receive five annual mammograms or physical breast examinations. They followed these women over a 25-year period, and concluded that yearly mammography in women aged 40-59 did not decrease breast cancer mortality "beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available."

Well, how many of us have taken care of women in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s with terminal breast cancer? How many of us would advise a mother, aunt, sister (or self) not to have routine mammography? Not many, I’m sure. There is the art of medicine and the science of medicine. Sometimes these two clash, but I believe the art of medicine is realizing that the science of medicine really doesn’t matter to dying patients and their family members. Sometimes, we have to act in the best interest of individual patients and not rely too heavily on the "data." Data changes, risk factors emerge, or research findings may prove to be skewed or wrong in hindsight. Explains Dr. Poornima Sharma, an oncologist/hematologist at the University of Maryland Baltimore-Washington Medical Center: "While the methodology, mammographic technique, and equipment used in the Canadian study is being assessed and compared to the mammography standards used in the United States, the standard in this country remains annual mammography starting at age 40."

Still, many women consider themselves at low risk for breast cancer if they have no close relatives with the disease. As erroneous as this assumption may be, this subset of women may be particularly vulnerable to the implication that yearly mammography is not needed.

So do this: Discuss screening mammography with your own family and then use those feelings when a teachable moment presents itself at bedside.

Our patients rely on us to look into their eyes and give them our best advice. Even though I am a hospitalist, there are still those women I feel compelled to counsel about screening mammography, and this study will not lessen my fervor.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

I remember that day like it was yesterday, though it occurred more than a decade ago. I stood leaning over a black entertainment center in my family room, legs wobbly, heart weary – a surreal and solemn snapshot in time. From a speaker streamed a now-favorite Donnie McClurkin song, called "Stand," with its introspective lyrics: "You’ve prayed and you’ve cried ... . After you’ve done all you can, you just stand."

In the next room I could hear her softly gurgling on her secretions. I needed a moment, no, two or three moments, to collect my thoughts and pull myself together before I returned to face the nightmare I was living. My mother was actively dying in my guestroom. Why? I believed then and, today, many years later, believe just as strongly it was because she had not been getting her mammograms.

As a writer, sometimes I struggle with how personal to get in my blogs, but rest assured. I got her permission to share her story while she was still very lucid and competent. You see, she did not want others’ lives to end as hers was ending. She realized, in her final stages of life, that things would have likely been much different had she had her screening mammograms as recommended.

By the time of her diagnosis in her early 60s, the cancer had already spread. Would a mammogram in her late 50s have saved her life? I believe so, and I’m not alone. So I take issue with a recent article published in BMJ that downplays the significance of mammography (BMJ 2014;348:g366).

In 1980, Canadian researchers randomized 89,835 women, aged 40-59 to receive five annual mammograms or physical breast examinations. They followed these women over a 25-year period, and concluded that yearly mammography in women aged 40-59 did not decrease breast cancer mortality "beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available."

Well, how many of us have taken care of women in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s with terminal breast cancer? How many of us would advise a mother, aunt, sister (or self) not to have routine mammography? Not many, I’m sure. There is the art of medicine and the science of medicine. Sometimes these two clash, but I believe the art of medicine is realizing that the science of medicine really doesn’t matter to dying patients and their family members. Sometimes, we have to act in the best interest of individual patients and not rely too heavily on the "data." Data changes, risk factors emerge, or research findings may prove to be skewed or wrong in hindsight. Explains Dr. Poornima Sharma, an oncologist/hematologist at the University of Maryland Baltimore-Washington Medical Center: "While the methodology, mammographic technique, and equipment used in the Canadian study is being assessed and compared to the mammography standards used in the United States, the standard in this country remains annual mammography starting at age 40."

Still, many women consider themselves at low risk for breast cancer if they have no close relatives with the disease. As erroneous as this assumption may be, this subset of women may be particularly vulnerable to the implication that yearly mammography is not needed.

So do this: Discuss screening mammography with your own family and then use those feelings when a teachable moment presents itself at bedside.

Our patients rely on us to look into their eyes and give them our best advice. Even though I am a hospitalist, there are still those women I feel compelled to counsel about screening mammography, and this study will not lessen my fervor.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

I remember that day like it was yesterday, though it occurred more than a decade ago. I stood leaning over a black entertainment center in my family room, legs wobbly, heart weary – a surreal and solemn snapshot in time. From a speaker streamed a now-favorite Donnie McClurkin song, called "Stand," with its introspective lyrics: "You’ve prayed and you’ve cried ... . After you’ve done all you can, you just stand."

In the next room I could hear her softly gurgling on her secretions. I needed a moment, no, two or three moments, to collect my thoughts and pull myself together before I returned to face the nightmare I was living. My mother was actively dying in my guestroom. Why? I believed then and, today, many years later, believe just as strongly it was because she had not been getting her mammograms.

As a writer, sometimes I struggle with how personal to get in my blogs, but rest assured. I got her permission to share her story while she was still very lucid and competent. You see, she did not want others’ lives to end as hers was ending. She realized, in her final stages of life, that things would have likely been much different had she had her screening mammograms as recommended.

By the time of her diagnosis in her early 60s, the cancer had already spread. Would a mammogram in her late 50s have saved her life? I believe so, and I’m not alone. So I take issue with a recent article published in BMJ that downplays the significance of mammography (BMJ 2014;348:g366).

In 1980, Canadian researchers randomized 89,835 women, aged 40-59 to receive five annual mammograms or physical breast examinations. They followed these women over a 25-year period, and concluded that yearly mammography in women aged 40-59 did not decrease breast cancer mortality "beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available."

Well, how many of us have taken care of women in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s with terminal breast cancer? How many of us would advise a mother, aunt, sister (or self) not to have routine mammography? Not many, I’m sure. There is the art of medicine and the science of medicine. Sometimes these two clash, but I believe the art of medicine is realizing that the science of medicine really doesn’t matter to dying patients and their family members. Sometimes, we have to act in the best interest of individual patients and not rely too heavily on the "data." Data changes, risk factors emerge, or research findings may prove to be skewed or wrong in hindsight. Explains Dr. Poornima Sharma, an oncologist/hematologist at the University of Maryland Baltimore-Washington Medical Center: "While the methodology, mammographic technique, and equipment used in the Canadian study is being assessed and compared to the mammography standards used in the United States, the standard in this country remains annual mammography starting at age 40."

Still, many women consider themselves at low risk for breast cancer if they have no close relatives with the disease. As erroneous as this assumption may be, this subset of women may be particularly vulnerable to the implication that yearly mammography is not needed.

So do this: Discuss screening mammography with your own family and then use those feelings when a teachable moment presents itself at bedside.

Our patients rely on us to look into their eyes and give them our best advice. Even though I am a hospitalist, there are still those women I feel compelled to counsel about screening mammography, and this study will not lessen my fervor.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.