User login

Implement a 6-P framework

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, arguably the biggest public health and economic catastrophe of modern times, elevated multiple deficiencies in public health infrastructures across the world, such as a slow or delayed response to suppress and mitigate the virus, an inadequately prepared and protected health care and public health workforce, and decentralized, siloed efforts.1 COVID-19 further highlighted the vulnerabilities of the health care, public health, and economic sectors.2,3 Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading and deadly infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and the patients they serve to a breaking point.

Hospital systems in the United States are not only at the crux of the current pandemic but are also well positioned to lead the response to the pandemic. Hospital administrators oversee nearly 33% of national health expenditure that amounts to the hospital-based care in the United States. Additionally, they may have an impact on nearly 30% of the expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities.4

The two primary goals underlying our proposed framework to target COVID-19 are based on the World Health Organization recommendations and lessons learned from countries such as South Korea that have successfully implemented these recommendations.5

1. Flatten the curve. According to the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, flattening the curve means that we must do everything that will help us to slow down the rate of infection, so the number of cases do not exceed the capacity of health systems.

2. Establish a standardized, interdisciplinary approach to flattening the curve. Pandemics can have major adverse consequences beyond health outcomes (e.g., economy) that can impact adherence to advisories and introduce multiple unintended consequences (e.g., deferred chronic care, unemployment). Managing the current pandemic and thoughtful consideration of and action regarding its ripple effects is heavily dependent on a standardized, interdisciplinary approach that is monitored, implemented, and evaluated well.

To achieve these two goals, we recommend establishing an interdisciplinary coalition representing multiple sectors. Our 6-P framework described below is intended to guide hospital administrators, to build the coalition, and to achieve these goals.

Structure of the pandemic coalition

A successful coalition invites a collaborative partnership involving senior members of respective disciplines, who would provide valuable, complementary perspectives in the coalition. We recommend hospital administrators take a lead in the formation of such a coalition. While we present the stakeholders and their roles below based on their intended influence and impact on the overall outcome of COVID-19, the basic guiding principles behind our 6-P framework remain true for any large-scale population health intervention.

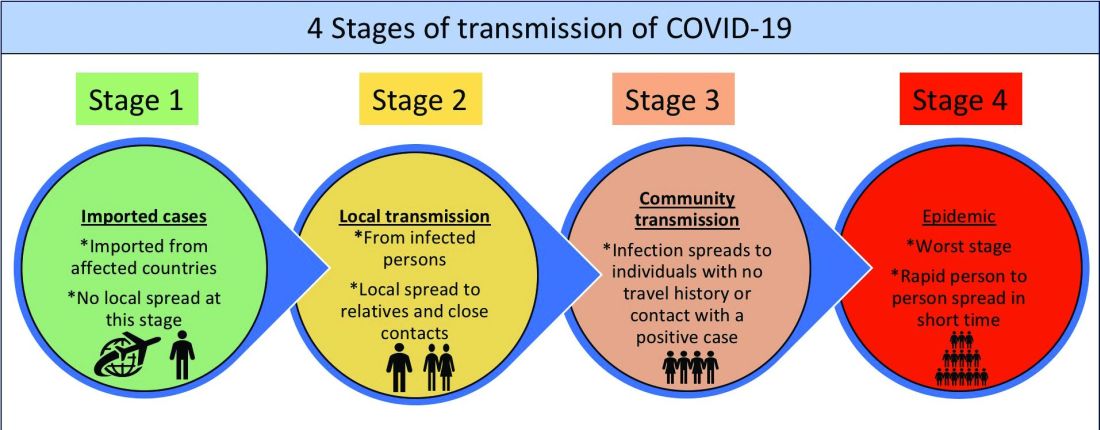

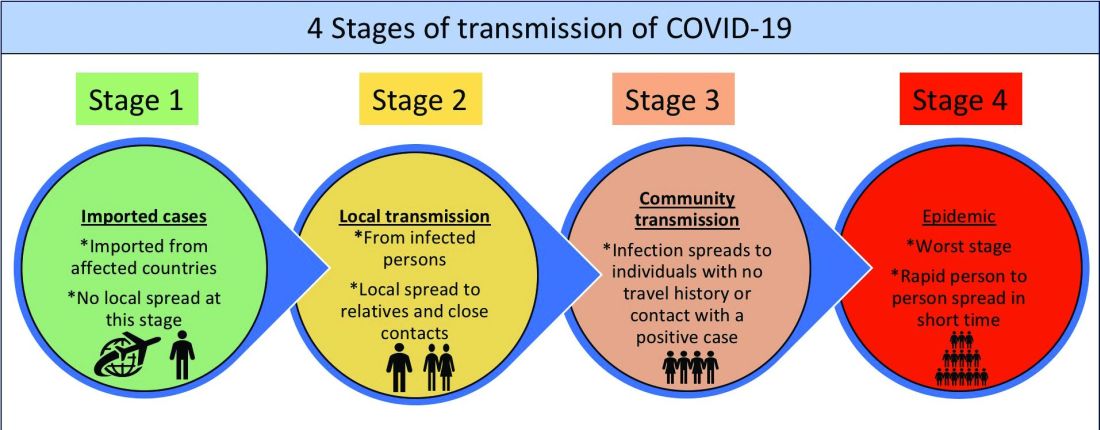

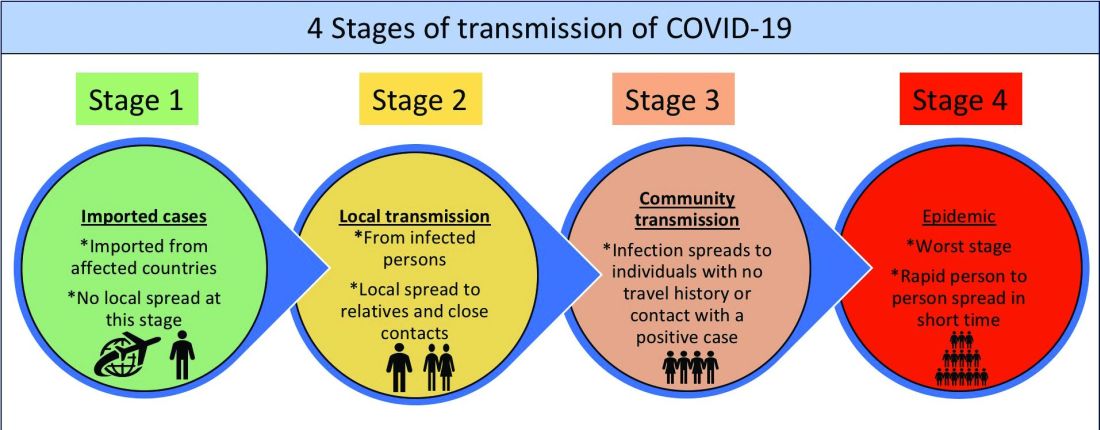

Although several models for staging the transmission of COVID-19 are available, we adopted a four-stage model followed by the Indian Council for Medical Research.6 Irrespective of the origin of the infection, we believe that the four-stage model can cultivate situational awareness that can help guide the strategic design and systematic implementation of interventions.

Our 6-P framework integrates the four-stage model of COVID-19 transmission to identify action items for each stakeholder group and appropriate strategies selected based on the stages targeted.

1. Policy makers: Policy makers at all levels are critical in establishing policies, orders, and advisories, as well as dedicating resources and infrastructure, to enhance adherence to recommendations and guidelines at the community and population levels.7 They can assist hospitals in workforce expansion across county/state/discipline lines (e.g., accelerate the licensing and credentialing process, authorize graduate medical trainees, nurse practitioners, and other allied health professionals). Policy revisions for data sharing, privacy, communication, liability, and telehealth expansion.82. Providers: The health of the health care workforce itself is at risk because of their frontline services. Their buy-in will be crucial in both the formulation and implementation of evidence- and practice-based guidelines.9 Rapid adoption of telehealth for care continuum, policy revisions for elective procedures, visitor restriction, surge, resurge planning, capacity expansion, effective population health management, and working with employee unions, professional staff organizations are few, but very important action items that need to be implemented.

3. Public health authorities: Representation of public health authorities will be crucial in standardizing data collection, management, and reporting; providing up-to-date guidelines and advisories; developing, implementing, and evaluating short- and long-term public health interventions; and preparing and helping communities throughout the course of the pandemic. They also play a key role in identifying and reducing barriers related to the expansion of testing and contact tracing efforts.

4. Payers: In the United States, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services oversees primary federally funded programs and serves as a point of reference for the American health care system. Having representation from all payer sources is crucial for achieving uniformity and standardization of the care process during the pandemic, with particular priority given to individuals and families who may have recently lost their health insurance because of job loss from COVID-19–related business furloughs, layoffs, and closures. Customer outreach initiatives, revision of patients’ out of pocket responsibilities, rapid claim settlement and denial management services, expansion of telehealth, elimination of prior authorization barriers, rapid credentialing of providers, data sharing, and assisting hospital systems in chronic disease management are examples of time-sensitive initiatives that are vital for population health management.

5. Partners: Establishing partnerships with pharma, health IT, labs, device industries, and other ancillary services is important to facilitate rapid innovation, production, and supply of essential medical devices and resources. These partners directly influence the outcomes of the pandemic and long-term health of the society through expansion of testing capability, contact tracing, leveraging technology for expanding access to COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 care, home monitoring of cases, innovation of treatment and prevention, and data sharing. Partners should consider options such as flexible medication delivery, electronic prescription services, and use of drones in supply chain to deliver test kits, test samples, medication, and blood products.

6. People/patients: Lastly and perhaps most critically, the trust, buy-in, and needs of the overall population are needed to enhance adherence to guidelines and recommendations. Many millions more than those who test positive for COVID-19 have and will continue to experience the crippling adverse economic, social, physical, and mental health effects of stay-at-home advisories, business and school closures, and physical distancing orders. Members of each community need to be heard in voicing their concerns and priorities and providing input on public health interventions to enhance acceptance and adherence (e.g., wear mask/face coverings in public, engage in physical distancing, etc.). Special attention should be given to managing chronic or existing medical problems and seek care when needed (e.g., avoid delaying of medical care).

An interdisciplinary and multipronged approach is necessary to address a complex, widespread, disruptive, and deadly pandemic such as COVID-19. The suggested activities put forth in our table are by no means exhaustive, nor do we expect all coalitions to be able to carry them all out. Our intention is that the 6-P framework encourages cross-sector collaboration to facilitate the design, implementation, evaluation, and scalability of preventive and intervention efforts based on the menu of items we have provided. Each coalition may determine which strategies they are able to prioritize and when within the context of specific national, regional, and local advisories, resulting in a tailored approach for each community or region that is thus better positioned for success.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark. He is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the department of community health sciences at Boston University and adjunct assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management and physician advisory services, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. He is an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi.

References

1. Powles J, Comim F. Public health infrastructure and knowledge, in Smith R et al. “Global Public Goods for Health.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2. Lombardi P, Petroni G. Virus outbreak pushes Italy’s health care system to the brink. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Mar 12. https://www.wsj.com/articles/virus-outbreak-pushes-italys-healthcare-system-to-the-brink-11583968769

3. Davies, R. How coronavirus is affecting the global economy. The Guardian. 2020 Feb 5. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/05/coronavirus-global-economy

4. National Center for Health Statistics. FastStats. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm.

5. World Health Organization. Country & Technical Guidance–Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance

6. Indian Council of Medical Research. Stages of transmission of COVID-19. https://main.icmr.nic.in/content/covid-19

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Prevention & treatment. 2020 Apr 24. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

8. Ostriker R. Cutbacks for some doctors and nurses as they battle on the front line. Boston Globe. 2020 Mar 27. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/27/metro/coronavirus-rages-doctors-hit-with-cuts-compensation/

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. News alert. 2020 Mar 26. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-news-alert-march-26-2020

Implement a 6-P framework

Implement a 6-P framework

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, arguably the biggest public health and economic catastrophe of modern times, elevated multiple deficiencies in public health infrastructures across the world, such as a slow or delayed response to suppress and mitigate the virus, an inadequately prepared and protected health care and public health workforce, and decentralized, siloed efforts.1 COVID-19 further highlighted the vulnerabilities of the health care, public health, and economic sectors.2,3 Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading and deadly infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and the patients they serve to a breaking point.

Hospital systems in the United States are not only at the crux of the current pandemic but are also well positioned to lead the response to the pandemic. Hospital administrators oversee nearly 33% of national health expenditure that amounts to the hospital-based care in the United States. Additionally, they may have an impact on nearly 30% of the expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities.4

The two primary goals underlying our proposed framework to target COVID-19 are based on the World Health Organization recommendations and lessons learned from countries such as South Korea that have successfully implemented these recommendations.5

1. Flatten the curve. According to the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, flattening the curve means that we must do everything that will help us to slow down the rate of infection, so the number of cases do not exceed the capacity of health systems.

2. Establish a standardized, interdisciplinary approach to flattening the curve. Pandemics can have major adverse consequences beyond health outcomes (e.g., economy) that can impact adherence to advisories and introduce multiple unintended consequences (e.g., deferred chronic care, unemployment). Managing the current pandemic and thoughtful consideration of and action regarding its ripple effects is heavily dependent on a standardized, interdisciplinary approach that is monitored, implemented, and evaluated well.

To achieve these two goals, we recommend establishing an interdisciplinary coalition representing multiple sectors. Our 6-P framework described below is intended to guide hospital administrators, to build the coalition, and to achieve these goals.

Structure of the pandemic coalition

A successful coalition invites a collaborative partnership involving senior members of respective disciplines, who would provide valuable, complementary perspectives in the coalition. We recommend hospital administrators take a lead in the formation of such a coalition. While we present the stakeholders and their roles below based on their intended influence and impact on the overall outcome of COVID-19, the basic guiding principles behind our 6-P framework remain true for any large-scale population health intervention.

Although several models for staging the transmission of COVID-19 are available, we adopted a four-stage model followed by the Indian Council for Medical Research.6 Irrespective of the origin of the infection, we believe that the four-stage model can cultivate situational awareness that can help guide the strategic design and systematic implementation of interventions.

Our 6-P framework integrates the four-stage model of COVID-19 transmission to identify action items for each stakeholder group and appropriate strategies selected based on the stages targeted.

1. Policy makers: Policy makers at all levels are critical in establishing policies, orders, and advisories, as well as dedicating resources and infrastructure, to enhance adherence to recommendations and guidelines at the community and population levels.7 They can assist hospitals in workforce expansion across county/state/discipline lines (e.g., accelerate the licensing and credentialing process, authorize graduate medical trainees, nurse practitioners, and other allied health professionals). Policy revisions for data sharing, privacy, communication, liability, and telehealth expansion.82. Providers: The health of the health care workforce itself is at risk because of their frontline services. Their buy-in will be crucial in both the formulation and implementation of evidence- and practice-based guidelines.9 Rapid adoption of telehealth for care continuum, policy revisions for elective procedures, visitor restriction, surge, resurge planning, capacity expansion, effective population health management, and working with employee unions, professional staff organizations are few, but very important action items that need to be implemented.

3. Public health authorities: Representation of public health authorities will be crucial in standardizing data collection, management, and reporting; providing up-to-date guidelines and advisories; developing, implementing, and evaluating short- and long-term public health interventions; and preparing and helping communities throughout the course of the pandemic. They also play a key role in identifying and reducing barriers related to the expansion of testing and contact tracing efforts.

4. Payers: In the United States, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services oversees primary federally funded programs and serves as a point of reference for the American health care system. Having representation from all payer sources is crucial for achieving uniformity and standardization of the care process during the pandemic, with particular priority given to individuals and families who may have recently lost their health insurance because of job loss from COVID-19–related business furloughs, layoffs, and closures. Customer outreach initiatives, revision of patients’ out of pocket responsibilities, rapid claim settlement and denial management services, expansion of telehealth, elimination of prior authorization barriers, rapid credentialing of providers, data sharing, and assisting hospital systems in chronic disease management are examples of time-sensitive initiatives that are vital for population health management.

5. Partners: Establishing partnerships with pharma, health IT, labs, device industries, and other ancillary services is important to facilitate rapid innovation, production, and supply of essential medical devices and resources. These partners directly influence the outcomes of the pandemic and long-term health of the society through expansion of testing capability, contact tracing, leveraging technology for expanding access to COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 care, home monitoring of cases, innovation of treatment and prevention, and data sharing. Partners should consider options such as flexible medication delivery, electronic prescription services, and use of drones in supply chain to deliver test kits, test samples, medication, and blood products.

6. People/patients: Lastly and perhaps most critically, the trust, buy-in, and needs of the overall population are needed to enhance adherence to guidelines and recommendations. Many millions more than those who test positive for COVID-19 have and will continue to experience the crippling adverse economic, social, physical, and mental health effects of stay-at-home advisories, business and school closures, and physical distancing orders. Members of each community need to be heard in voicing their concerns and priorities and providing input on public health interventions to enhance acceptance and adherence (e.g., wear mask/face coverings in public, engage in physical distancing, etc.). Special attention should be given to managing chronic or existing medical problems and seek care when needed (e.g., avoid delaying of medical care).

An interdisciplinary and multipronged approach is necessary to address a complex, widespread, disruptive, and deadly pandemic such as COVID-19. The suggested activities put forth in our table are by no means exhaustive, nor do we expect all coalitions to be able to carry them all out. Our intention is that the 6-P framework encourages cross-sector collaboration to facilitate the design, implementation, evaluation, and scalability of preventive and intervention efforts based on the menu of items we have provided. Each coalition may determine which strategies they are able to prioritize and when within the context of specific national, regional, and local advisories, resulting in a tailored approach for each community or region that is thus better positioned for success.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark. He is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the department of community health sciences at Boston University and adjunct assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management and physician advisory services, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. He is an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi.

References

1. Powles J, Comim F. Public health infrastructure and knowledge, in Smith R et al. “Global Public Goods for Health.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2. Lombardi P, Petroni G. Virus outbreak pushes Italy’s health care system to the brink. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Mar 12. https://www.wsj.com/articles/virus-outbreak-pushes-italys-healthcare-system-to-the-brink-11583968769

3. Davies, R. How coronavirus is affecting the global economy. The Guardian. 2020 Feb 5. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/05/coronavirus-global-economy

4. National Center for Health Statistics. FastStats. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm.

5. World Health Organization. Country & Technical Guidance–Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance

6. Indian Council of Medical Research. Stages of transmission of COVID-19. https://main.icmr.nic.in/content/covid-19

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Prevention & treatment. 2020 Apr 24. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

8. Ostriker R. Cutbacks for some doctors and nurses as they battle on the front line. Boston Globe. 2020 Mar 27. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/27/metro/coronavirus-rages-doctors-hit-with-cuts-compensation/

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. News alert. 2020 Mar 26. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-news-alert-march-26-2020

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, arguably the biggest public health and economic catastrophe of modern times, elevated multiple deficiencies in public health infrastructures across the world, such as a slow or delayed response to suppress and mitigate the virus, an inadequately prepared and protected health care and public health workforce, and decentralized, siloed efforts.1 COVID-19 further highlighted the vulnerabilities of the health care, public health, and economic sectors.2,3 Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading and deadly infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and the patients they serve to a breaking point.

Hospital systems in the United States are not only at the crux of the current pandemic but are also well positioned to lead the response to the pandemic. Hospital administrators oversee nearly 33% of national health expenditure that amounts to the hospital-based care in the United States. Additionally, they may have an impact on nearly 30% of the expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities.4

The two primary goals underlying our proposed framework to target COVID-19 are based on the World Health Organization recommendations and lessons learned from countries such as South Korea that have successfully implemented these recommendations.5

1. Flatten the curve. According to the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, flattening the curve means that we must do everything that will help us to slow down the rate of infection, so the number of cases do not exceed the capacity of health systems.

2. Establish a standardized, interdisciplinary approach to flattening the curve. Pandemics can have major adverse consequences beyond health outcomes (e.g., economy) that can impact adherence to advisories and introduce multiple unintended consequences (e.g., deferred chronic care, unemployment). Managing the current pandemic and thoughtful consideration of and action regarding its ripple effects is heavily dependent on a standardized, interdisciplinary approach that is monitored, implemented, and evaluated well.

To achieve these two goals, we recommend establishing an interdisciplinary coalition representing multiple sectors. Our 6-P framework described below is intended to guide hospital administrators, to build the coalition, and to achieve these goals.

Structure of the pandemic coalition

A successful coalition invites a collaborative partnership involving senior members of respective disciplines, who would provide valuable, complementary perspectives in the coalition. We recommend hospital administrators take a lead in the formation of such a coalition. While we present the stakeholders and their roles below based on their intended influence and impact on the overall outcome of COVID-19, the basic guiding principles behind our 6-P framework remain true for any large-scale population health intervention.

Although several models for staging the transmission of COVID-19 are available, we adopted a four-stage model followed by the Indian Council for Medical Research.6 Irrespective of the origin of the infection, we believe that the four-stage model can cultivate situational awareness that can help guide the strategic design and systematic implementation of interventions.

Our 6-P framework integrates the four-stage model of COVID-19 transmission to identify action items for each stakeholder group and appropriate strategies selected based on the stages targeted.

1. Policy makers: Policy makers at all levels are critical in establishing policies, orders, and advisories, as well as dedicating resources and infrastructure, to enhance adherence to recommendations and guidelines at the community and population levels.7 They can assist hospitals in workforce expansion across county/state/discipline lines (e.g., accelerate the licensing and credentialing process, authorize graduate medical trainees, nurse practitioners, and other allied health professionals). Policy revisions for data sharing, privacy, communication, liability, and telehealth expansion.82. Providers: The health of the health care workforce itself is at risk because of their frontline services. Their buy-in will be crucial in both the formulation and implementation of evidence- and practice-based guidelines.9 Rapid adoption of telehealth for care continuum, policy revisions for elective procedures, visitor restriction, surge, resurge planning, capacity expansion, effective population health management, and working with employee unions, professional staff organizations are few, but very important action items that need to be implemented.

3. Public health authorities: Representation of public health authorities will be crucial in standardizing data collection, management, and reporting; providing up-to-date guidelines and advisories; developing, implementing, and evaluating short- and long-term public health interventions; and preparing and helping communities throughout the course of the pandemic. They also play a key role in identifying and reducing barriers related to the expansion of testing and contact tracing efforts.

4. Payers: In the United States, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services oversees primary federally funded programs and serves as a point of reference for the American health care system. Having representation from all payer sources is crucial for achieving uniformity and standardization of the care process during the pandemic, with particular priority given to individuals and families who may have recently lost their health insurance because of job loss from COVID-19–related business furloughs, layoffs, and closures. Customer outreach initiatives, revision of patients’ out of pocket responsibilities, rapid claim settlement and denial management services, expansion of telehealth, elimination of prior authorization barriers, rapid credentialing of providers, data sharing, and assisting hospital systems in chronic disease management are examples of time-sensitive initiatives that are vital for population health management.

5. Partners: Establishing partnerships with pharma, health IT, labs, device industries, and other ancillary services is important to facilitate rapid innovation, production, and supply of essential medical devices and resources. These partners directly influence the outcomes of the pandemic and long-term health of the society through expansion of testing capability, contact tracing, leveraging technology for expanding access to COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 care, home monitoring of cases, innovation of treatment and prevention, and data sharing. Partners should consider options such as flexible medication delivery, electronic prescription services, and use of drones in supply chain to deliver test kits, test samples, medication, and blood products.

6. People/patients: Lastly and perhaps most critically, the trust, buy-in, and needs of the overall population are needed to enhance adherence to guidelines and recommendations. Many millions more than those who test positive for COVID-19 have and will continue to experience the crippling adverse economic, social, physical, and mental health effects of stay-at-home advisories, business and school closures, and physical distancing orders. Members of each community need to be heard in voicing their concerns and priorities and providing input on public health interventions to enhance acceptance and adherence (e.g., wear mask/face coverings in public, engage in physical distancing, etc.). Special attention should be given to managing chronic or existing medical problems and seek care when needed (e.g., avoid delaying of medical care).

An interdisciplinary and multipronged approach is necessary to address a complex, widespread, disruptive, and deadly pandemic such as COVID-19. The suggested activities put forth in our table are by no means exhaustive, nor do we expect all coalitions to be able to carry them all out. Our intention is that the 6-P framework encourages cross-sector collaboration to facilitate the design, implementation, evaluation, and scalability of preventive and intervention efforts based on the menu of items we have provided. Each coalition may determine which strategies they are able to prioritize and when within the context of specific national, regional, and local advisories, resulting in a tailored approach for each community or region that is thus better positioned for success.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark. He is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the department of community health sciences at Boston University and adjunct assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management and physician advisory services, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. He is an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi.

References

1. Powles J, Comim F. Public health infrastructure and knowledge, in Smith R et al. “Global Public Goods for Health.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2. Lombardi P, Petroni G. Virus outbreak pushes Italy’s health care system to the brink. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Mar 12. https://www.wsj.com/articles/virus-outbreak-pushes-italys-healthcare-system-to-the-brink-11583968769

3. Davies, R. How coronavirus is affecting the global economy. The Guardian. 2020 Feb 5. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/05/coronavirus-global-economy

4. National Center for Health Statistics. FastStats. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm.

5. World Health Organization. Country & Technical Guidance–Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance

6. Indian Council of Medical Research. Stages of transmission of COVID-19. https://main.icmr.nic.in/content/covid-19

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Prevention & treatment. 2020 Apr 24. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

8. Ostriker R. Cutbacks for some doctors and nurses as they battle on the front line. Boston Globe. 2020 Mar 27. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/27/metro/coronavirus-rages-doctors-hit-with-cuts-compensation/

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. News alert. 2020 Mar 26. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-news-alert-march-26-2020