User login

Wilma F. Bergfeld, MD, one of only five women in her medical school class of 1964 and the third female in her dermatology residency program, had recently been appointed as a junior clinical dermatologist and head of dermatopathology at the Cleveland Clinic when she was told by a superior that she would not be promoted or invited to serve on any committee or decision-making group.

“I was told I should go home at night and take care of my husband and two children,” she recalled of that moment in the 1970s. The comment made her feel “outraged,” and it drove her, calmly and steadily, to work harder and to “challenge the system.”

Dr. Bergfeld not only was elected to the Cleveland Clinic’s board of governors and board of trustees and served as president of the Clinic’s staff in 1990, she also became the first woman president of the American Academy of Dermatology (1992) and led numerous other dermatologic organizations. Much earlier on, in 1973, to help fulfill her vision of “women helping women,” she had also founded the Women’s Dermatologic Society (WDS). Three years earlier, in 1970, 6.9% of the approximately 4,000 dermatologists in the United States were women, according to the American Medical Association.

Today, when she goes to work as the long-time director of the Clinic’s dermatopathology fellowship and professor of dermatology and pathology at the Cleveland Clinic Educational Foundation, she sees a transformed staff and, more broadly, a national physician workforce in which women made up almost 50% of active dermatologists in 2017 and almost 60% of dermatology residents in 2018, according to data from the American Association of Medical Colleges.

It’s a different and better world, she and other women dermatologists said, but one in which women must continue to mentor other women and continue to challenge the system. Achieving work-life balance, fairer compensation, and a greater proportion of women in the higher ranks of academia are all on their work list.

Women’s impact on the specialty

Dr. Bergfeld and Molly Hinshaw, MD, the current president of the WDS, said they believe women are drawn to dermatology for its visual nature, the growth in diagnostic tests and therapies, and the opportunity to diagnose early and prevent progression of disease in patients of all ages. “It’s a small but mighty specialty,” said Dr. Hinshaw, associate professor of dermatology and section chief of dermatopathology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

It’s also a versatile specialty with a variety of subspecialties and niches to pursue – and women have been stepping in to fill unmet needs, Dr. Hinshaw said. “Women dermatologists are directing vulvar specialty clinics across the country, for example. There aren’t that many, but they’re filling an important niche. We have one at [our university] and it is packed.”

Women have also been drawn to the in-demand subspecialty of pediatric dermatology, she noted. They now make up more than two-thirds of all pediatric dermatologists, and many in practice have trained the old-fashioned way, completing two residencies. “That’s [involved] self-selection into an additional year of years training and a commitment to caring for special populations that, quite honestly, takes more time,” said Dr. Hinshaw, who, as part of her dermatology practice, runs a nail clinic at UW Health in Madison.

Amy S. Paller, MD, who chairs the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, where she is professor of dermatology and pediatrics and directs the Skin Biology & Diseases Resource-Based Center, is one of these women. She took a long and determined journey into the subspecialty, encountering bias and discouragement while actively seeking out mentors who helped her advance.

While in medical school at Stanford (Calif.) University in the late 1970s in a class “very progressively” made up of about one-third women, Dr. Paller met Alvin Jacobs, MD, who, in 1975, had founded the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “There wasn’t much pediatric dermatology in the world at the time, and it was Al who helped [me realize] that it combined my love of genetic research with my [desire] to work with children,” she recalled.

Per Dr. Jacob’s advice, she went to Northwestern to train in both pediatrics and dermatology under Nancy Esterly, MD, who “is considered by many to be the mother of pediatric dermatology.” And knowing that she wanted to do research, Dr. Paller also worked with Ruth Freinkel, MD, who “was the strongest bench researcher” at Northwestern. (Dr. Freinkel had been one of the first female dermatology residents at Harvard and was the first full-time faculty member in dermatology at Northwestern).

After completing postdoctoral research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Dr. Paller returned to Chicago and assumed Dr. Esterly’s position as chief of dermatology at the Children’s National Hospital of Chicago. It was there that “someone in a leadership position questioned me about how I could possibly be a scientist, a strong clinician, and a good mother to my three children – and suggested that I drop research,” Dr. Paller recalled.

“I think this person was trying to be helpful to me, but I was shocked,” she said. Just as Dr. Bergfeld had done, Dr. Paller channeled her frustration into new pursuits.

“It made me go home and think, how could I strengthen myself? What else could I do?” she said. “Soon after, with a highly supportive husband, I did a ‘pseudosabbatical,’ basically spending every ounce of spare time I had working with one of the premier female scientists in the country, Elaine Fuchs, and learning molecular biology” in her lab at the University of Chicago.

“I think we’ve all had discrimination along the way. Sometimes there’s implicit bias and sometimes there’s overt bias,” said Dr. Paller, who in 2004 led the society which her mentor Dr. Jacobs had founded several decades earlier. “I just jumped right in, and that’s enabled me to find good role models.”

Across dermatology broadly, the often holistic nature of the specialty – of the ability to peer into the body and its internal health – is another quality that women have been drawn to and advanced, Dr. Hinshaw said. “One of the reasons why I chose dermatology is because it’s a window to total patient health. Patients often see their dermatologists as physicians who help them identify next steps in their health care, who can help them address issues related to their overall health and well-being, including their mental health.”

In a WDS membership survey conducted in 2018, most respondents reported that they frequently or occasionally detect and diagnose systemic/internal diseases and conditions in their female patients, and that they consult and collaborate with different kinds of physicians (Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018 Nov 15;4[4]:189-92).

And in a March 2019 “Dialogues in Dermatology” podcast episode on the history and advancement of women in dermatology produced by the American Academy of Dermatology, Pearl Grimes, MD, a clinical professor of dermatology of the University of California, Los Angeles, and then-president of the WDS, described why “total women’s health” had become an additional focus for the society.

“We’re already gatekeepers” in many respects, Dr. Grimes said. “In addition to my addressing specific skin issues, my patients query me on hormone issues, on nutrition, on stress-related issues….and on [what other physicians they should see].”

Phoebe Rich, MD, who owns a small all-woman practice and a research center in Portland, Oregon, said that, in general, many women also communicate and practice in a way that facilitates holistic care. “These qualities aren’t exclusive to women, but women are very caring. We take time and are interested in [patients’] lives in general, not just their disease.”

Disparities in academia

Dermatology departments in academic medicine have burgeoned in size in the past 50 years, and women are well represented overall. In 2018, women comprised 51.2% of dermatology department faculty – up from 10.8% in 1970 – a current proportion that ranks fifth among specialties for the proportion of female faculty, according to a cross-sectional study of faculty diversity trends using data from the AAMC faculty roster (JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jan 8;156[3]:280-7).

The AAMC data show the share of women dermatology faculty declining at each subsequent rank, however – a finding that suggests that women are not promoted as quickly or to the same levels of leadership as men, the report’s authors noted. (Dermatology isn’t alone: The AAMC issued a call to action on gender equity in medicine this year, citing this inverse association.)

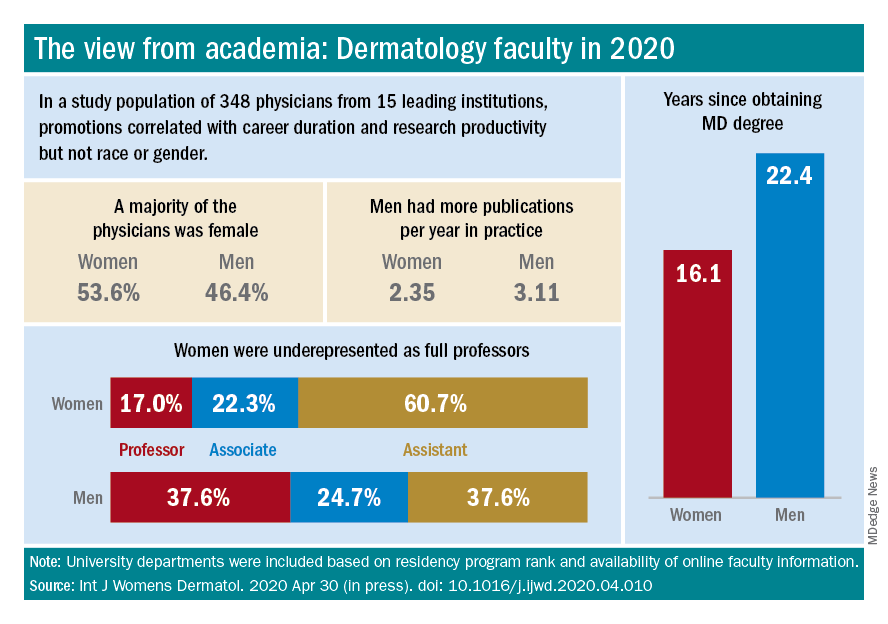

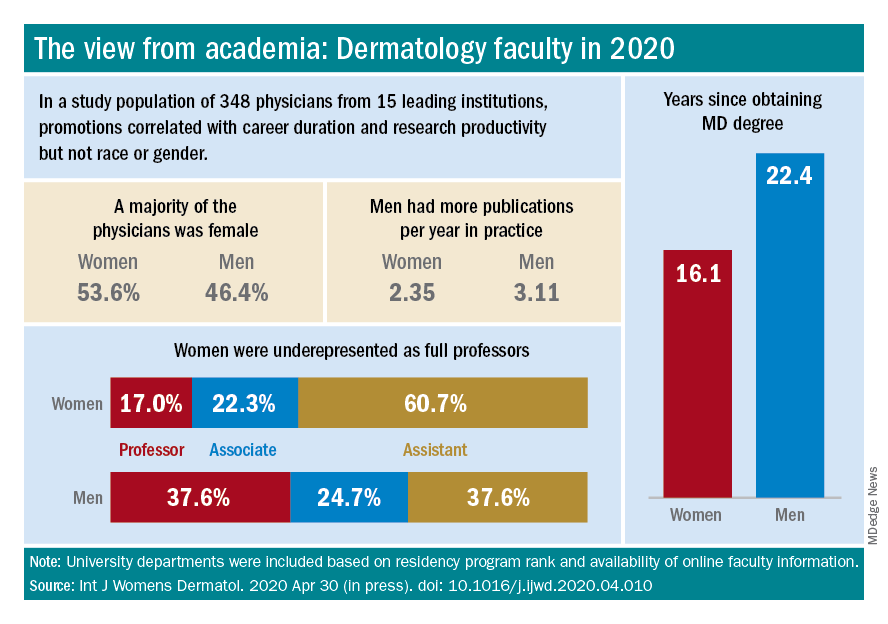

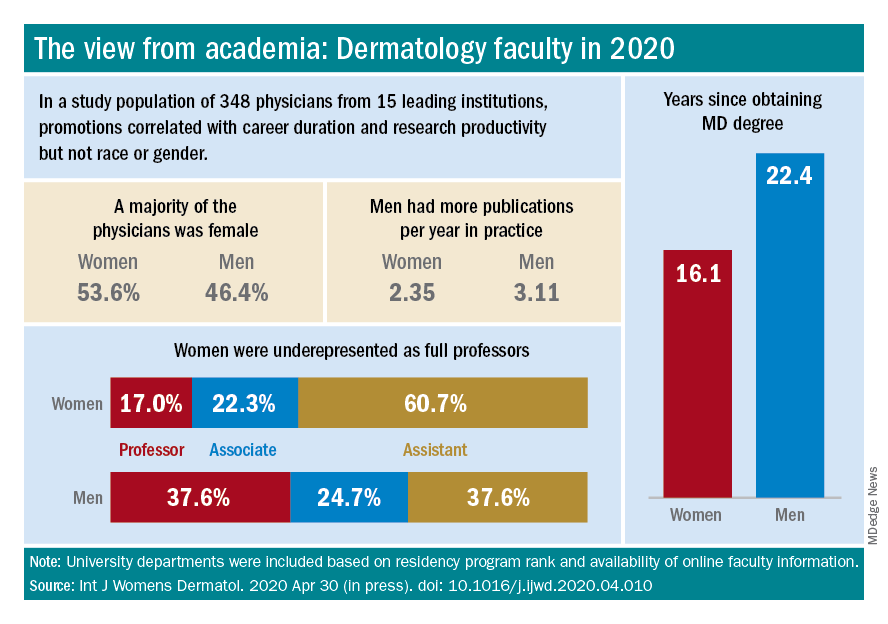

Another recently published study of gender trends in academic dermatology – this one looking at a smaller sample of data from 15 institutions – similarly found that women dermatologists made up a majority of faculty (53.6%) and were well represented as assistant professors (60.7%) but underrepresented as full professors (17%).

This study differed from the larger AAMC study, however, in that it controlled for “achievement indicators” – career duration, publications per year, and National Institutes of Health research funding – and found that gender alone was not associated with higher rank. Instead, promotions were correlated most significantly with NIH research funding and also with career duration and publications per year.

“If research achievement is to be used as a benchmark for academic promotion, increased efforts are needed to support the research activities of women,” the authors wrote, adding that recognition should be given to other factors as well.

Dr. Paller and Dr. Hinshaw both described the situation as complex and multifaceted. Some research on promotion in academia in general – but not all – has suggested that women do need to publish more than men in order to be promoted. But “the promotion process also has within it the ability to use judgment [about] the impact and merits of work,” said Dr. Hinshaw. “Not all publications [and levels of authorship] may be considered equal, for instance.”

Dr. Hinshaw said she is also concerned by data showing that women still perform the majority of household duties, “even in households in which both partners work outside the home equivalently.” As long as this is the case, women may be “inherently disadvantaged” in their ability to have adequate research time and to advance.

From where she sits, Dr. Paller sees several factors at play: “The pipeline, achievement during the pipeline, and decision-making about advancement” on the part of women themselves. Having served on search committees for top leadership in specialties in which women are well represented, she said, “I’ve seen fewer women who’ve come forward and been interested in rising into a chair or a dean position.”

And “having talked to so many women,” Dr. Paller added, “I think there’s a phenomenon where it’s harder for women to accept positions [that require] a significant change.”

Women “are nurturers, which makes them extremely good [leaders] and chairs, but it also makes it harder to make life changes that affect the people they love,” she said, noting that becoming a department chair or a dean often involves moving. “I also think that women in general are happier and committed to what they’re [currently] doing.”

Dr. Paller is optimistic that, with the support of department chairs and continued attention to role modeling and mentoring, the portrait of women in academic dermatology will continue to improve. Currently, 34 chairs of dermatology departments are female, she noted. “That number was 11 less 15 years ago.”

In the meantime, researchers are increasingly documenting trends in women’s editorships of journals as well as leadership and speaking opportunities at professional conferences.

The authors of one study published this year, for instance, reviewed the editorial boards of dermatology journals and found that women occupied 18% of editor in chief roles, 36% of deputy editor positions, and 22% of overall editorial board roles (Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Sep 12;6[1]:20-4). Other research shows women comprising 43% of all authorships across 23 dermatologic journals from 2008 to May 2017, 50.2% of first authorships, and 33.1% of last authorships (BMJ Open. 2018 Apr 13;8[4]:e020089).

Both in academic medicine and in practice, a gender pay gap still affects women physicians across the board. Medscape’s 2020 dermatologist compensation report shows male dermatologists earning about 12% more than their female peers (average, $435,000 vs. $387,000, respectively), while the average number of hours per week spent seeing patients is similar (36.2 vs. 35.6 hours, respectively).

And in its 2020 statement on gender equity, the AAMC said that women in academic medicine are offered less in starting salary, negotiated pay, and other forms of compensation than men “despite equal effort, rank, training, and experience.”

It’s complicated to tease apart all the factors that may be involved – but important to keep challenging the system, said Dr. Bergfeld, who was a long-time board adviser for Dermatology News. “I was underpaid,” she noted, and “this was only rectified in the last 10 years.”

Work-life balance

In the AAD podcast on women in dermatology, Dr. Grimes said that achieving a healthy and balanced work life remains one of the greatest challenges for women dermatologists – and it may be even greater than in the past given the growing numbers of group practices. “When women enter the realm of group practice, they have less flexibility in controlling their time and their own schedules.”

If Anna Hare, MD, is any indication, younger dermatologists may buck this trend. The daughter of Dr. Rich in Portland, Dr. Hare joined her mother’s dermatology practice and research center knowing that she’d have “the respect and flexibility for deciding how I want to practice.”

Younger dermatologists, she said, place “more of an emphasis on work-life balance and quality of life.”

Fortunately, said Dr. Bergfeld, women have advanced enough in the ranks of dermatology that, in networking, in mentorship, and in workplace settings, attention can be paid more fully to discussions about work-life management – “how to manage your life when you’re working with family and kids and parents.”

In the 1970s, at the Cleveland Clinic, “there were only five women on staff and we were fighting for [basic] rights,” she said. “We wanted equality – we were [perceived as] little worker bees….We needed to climb as the men did to positions of leadership and address the problems of women.”

In pursuing their goals and making further progress, women dermatologists today should be “steady and calm,” she advised. Formally acquiring leadership skills and communication skills is a timeless need. And when there are biases or conflicts, “you cannot have righteous indignation, you cannot have revenge. You have to calm yourself and move forward.”

Wilma F. Bergfeld, MD, one of only five women in her medical school class of 1964 and the third female in her dermatology residency program, had recently been appointed as a junior clinical dermatologist and head of dermatopathology at the Cleveland Clinic when she was told by a superior that she would not be promoted or invited to serve on any committee or decision-making group.

“I was told I should go home at night and take care of my husband and two children,” she recalled of that moment in the 1970s. The comment made her feel “outraged,” and it drove her, calmly and steadily, to work harder and to “challenge the system.”

Dr. Bergfeld not only was elected to the Cleveland Clinic’s board of governors and board of trustees and served as president of the Clinic’s staff in 1990, she also became the first woman president of the American Academy of Dermatology (1992) and led numerous other dermatologic organizations. Much earlier on, in 1973, to help fulfill her vision of “women helping women,” she had also founded the Women’s Dermatologic Society (WDS). Three years earlier, in 1970, 6.9% of the approximately 4,000 dermatologists in the United States were women, according to the American Medical Association.

Today, when she goes to work as the long-time director of the Clinic’s dermatopathology fellowship and professor of dermatology and pathology at the Cleveland Clinic Educational Foundation, she sees a transformed staff and, more broadly, a national physician workforce in which women made up almost 50% of active dermatologists in 2017 and almost 60% of dermatology residents in 2018, according to data from the American Association of Medical Colleges.

It’s a different and better world, she and other women dermatologists said, but one in which women must continue to mentor other women and continue to challenge the system. Achieving work-life balance, fairer compensation, and a greater proportion of women in the higher ranks of academia are all on their work list.

Women’s impact on the specialty

Dr. Bergfeld and Molly Hinshaw, MD, the current president of the WDS, said they believe women are drawn to dermatology for its visual nature, the growth in diagnostic tests and therapies, and the opportunity to diagnose early and prevent progression of disease in patients of all ages. “It’s a small but mighty specialty,” said Dr. Hinshaw, associate professor of dermatology and section chief of dermatopathology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

It’s also a versatile specialty with a variety of subspecialties and niches to pursue – and women have been stepping in to fill unmet needs, Dr. Hinshaw said. “Women dermatologists are directing vulvar specialty clinics across the country, for example. There aren’t that many, but they’re filling an important niche. We have one at [our university] and it is packed.”

Women have also been drawn to the in-demand subspecialty of pediatric dermatology, she noted. They now make up more than two-thirds of all pediatric dermatologists, and many in practice have trained the old-fashioned way, completing two residencies. “That’s [involved] self-selection into an additional year of years training and a commitment to caring for special populations that, quite honestly, takes more time,” said Dr. Hinshaw, who, as part of her dermatology practice, runs a nail clinic at UW Health in Madison.

Amy S. Paller, MD, who chairs the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, where she is professor of dermatology and pediatrics and directs the Skin Biology & Diseases Resource-Based Center, is one of these women. She took a long and determined journey into the subspecialty, encountering bias and discouragement while actively seeking out mentors who helped her advance.

While in medical school at Stanford (Calif.) University in the late 1970s in a class “very progressively” made up of about one-third women, Dr. Paller met Alvin Jacobs, MD, who, in 1975, had founded the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “There wasn’t much pediatric dermatology in the world at the time, and it was Al who helped [me realize] that it combined my love of genetic research with my [desire] to work with children,” she recalled.

Per Dr. Jacob’s advice, she went to Northwestern to train in both pediatrics and dermatology under Nancy Esterly, MD, who “is considered by many to be the mother of pediatric dermatology.” And knowing that she wanted to do research, Dr. Paller also worked with Ruth Freinkel, MD, who “was the strongest bench researcher” at Northwestern. (Dr. Freinkel had been one of the first female dermatology residents at Harvard and was the first full-time faculty member in dermatology at Northwestern).

After completing postdoctoral research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Dr. Paller returned to Chicago and assumed Dr. Esterly’s position as chief of dermatology at the Children’s National Hospital of Chicago. It was there that “someone in a leadership position questioned me about how I could possibly be a scientist, a strong clinician, and a good mother to my three children – and suggested that I drop research,” Dr. Paller recalled.

“I think this person was trying to be helpful to me, but I was shocked,” she said. Just as Dr. Bergfeld had done, Dr. Paller channeled her frustration into new pursuits.

“It made me go home and think, how could I strengthen myself? What else could I do?” she said. “Soon after, with a highly supportive husband, I did a ‘pseudosabbatical,’ basically spending every ounce of spare time I had working with one of the premier female scientists in the country, Elaine Fuchs, and learning molecular biology” in her lab at the University of Chicago.

“I think we’ve all had discrimination along the way. Sometimes there’s implicit bias and sometimes there’s overt bias,” said Dr. Paller, who in 2004 led the society which her mentor Dr. Jacobs had founded several decades earlier. “I just jumped right in, and that’s enabled me to find good role models.”

Across dermatology broadly, the often holistic nature of the specialty – of the ability to peer into the body and its internal health – is another quality that women have been drawn to and advanced, Dr. Hinshaw said. “One of the reasons why I chose dermatology is because it’s a window to total patient health. Patients often see their dermatologists as physicians who help them identify next steps in their health care, who can help them address issues related to their overall health and well-being, including their mental health.”

In a WDS membership survey conducted in 2018, most respondents reported that they frequently or occasionally detect and diagnose systemic/internal diseases and conditions in their female patients, and that they consult and collaborate with different kinds of physicians (Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018 Nov 15;4[4]:189-92).

And in a March 2019 “Dialogues in Dermatology” podcast episode on the history and advancement of women in dermatology produced by the American Academy of Dermatology, Pearl Grimes, MD, a clinical professor of dermatology of the University of California, Los Angeles, and then-president of the WDS, described why “total women’s health” had become an additional focus for the society.

“We’re already gatekeepers” in many respects, Dr. Grimes said. “In addition to my addressing specific skin issues, my patients query me on hormone issues, on nutrition, on stress-related issues….and on [what other physicians they should see].”

Phoebe Rich, MD, who owns a small all-woman practice and a research center in Portland, Oregon, said that, in general, many women also communicate and practice in a way that facilitates holistic care. “These qualities aren’t exclusive to women, but women are very caring. We take time and are interested in [patients’] lives in general, not just their disease.”

Disparities in academia

Dermatology departments in academic medicine have burgeoned in size in the past 50 years, and women are well represented overall. In 2018, women comprised 51.2% of dermatology department faculty – up from 10.8% in 1970 – a current proportion that ranks fifth among specialties for the proportion of female faculty, according to a cross-sectional study of faculty diversity trends using data from the AAMC faculty roster (JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jan 8;156[3]:280-7).

The AAMC data show the share of women dermatology faculty declining at each subsequent rank, however – a finding that suggests that women are not promoted as quickly or to the same levels of leadership as men, the report’s authors noted. (Dermatology isn’t alone: The AAMC issued a call to action on gender equity in medicine this year, citing this inverse association.)

Another recently published study of gender trends in academic dermatology – this one looking at a smaller sample of data from 15 institutions – similarly found that women dermatologists made up a majority of faculty (53.6%) and were well represented as assistant professors (60.7%) but underrepresented as full professors (17%).

This study differed from the larger AAMC study, however, in that it controlled for “achievement indicators” – career duration, publications per year, and National Institutes of Health research funding – and found that gender alone was not associated with higher rank. Instead, promotions were correlated most significantly with NIH research funding and also with career duration and publications per year.

“If research achievement is to be used as a benchmark for academic promotion, increased efforts are needed to support the research activities of women,” the authors wrote, adding that recognition should be given to other factors as well.

Dr. Paller and Dr. Hinshaw both described the situation as complex and multifaceted. Some research on promotion in academia in general – but not all – has suggested that women do need to publish more than men in order to be promoted. But “the promotion process also has within it the ability to use judgment [about] the impact and merits of work,” said Dr. Hinshaw. “Not all publications [and levels of authorship] may be considered equal, for instance.”

Dr. Hinshaw said she is also concerned by data showing that women still perform the majority of household duties, “even in households in which both partners work outside the home equivalently.” As long as this is the case, women may be “inherently disadvantaged” in their ability to have adequate research time and to advance.

From where she sits, Dr. Paller sees several factors at play: “The pipeline, achievement during the pipeline, and decision-making about advancement” on the part of women themselves. Having served on search committees for top leadership in specialties in which women are well represented, she said, “I’ve seen fewer women who’ve come forward and been interested in rising into a chair or a dean position.”

And “having talked to so many women,” Dr. Paller added, “I think there’s a phenomenon where it’s harder for women to accept positions [that require] a significant change.”

Women “are nurturers, which makes them extremely good [leaders] and chairs, but it also makes it harder to make life changes that affect the people they love,” she said, noting that becoming a department chair or a dean often involves moving. “I also think that women in general are happier and committed to what they’re [currently] doing.”

Dr. Paller is optimistic that, with the support of department chairs and continued attention to role modeling and mentoring, the portrait of women in academic dermatology will continue to improve. Currently, 34 chairs of dermatology departments are female, she noted. “That number was 11 less 15 years ago.”

In the meantime, researchers are increasingly documenting trends in women’s editorships of journals as well as leadership and speaking opportunities at professional conferences.

The authors of one study published this year, for instance, reviewed the editorial boards of dermatology journals and found that women occupied 18% of editor in chief roles, 36% of deputy editor positions, and 22% of overall editorial board roles (Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Sep 12;6[1]:20-4). Other research shows women comprising 43% of all authorships across 23 dermatologic journals from 2008 to May 2017, 50.2% of first authorships, and 33.1% of last authorships (BMJ Open. 2018 Apr 13;8[4]:e020089).

Both in academic medicine and in practice, a gender pay gap still affects women physicians across the board. Medscape’s 2020 dermatologist compensation report shows male dermatologists earning about 12% more than their female peers (average, $435,000 vs. $387,000, respectively), while the average number of hours per week spent seeing patients is similar (36.2 vs. 35.6 hours, respectively).

And in its 2020 statement on gender equity, the AAMC said that women in academic medicine are offered less in starting salary, negotiated pay, and other forms of compensation than men “despite equal effort, rank, training, and experience.”

It’s complicated to tease apart all the factors that may be involved – but important to keep challenging the system, said Dr. Bergfeld, who was a long-time board adviser for Dermatology News. “I was underpaid,” she noted, and “this was only rectified in the last 10 years.”

Work-life balance

In the AAD podcast on women in dermatology, Dr. Grimes said that achieving a healthy and balanced work life remains one of the greatest challenges for women dermatologists – and it may be even greater than in the past given the growing numbers of group practices. “When women enter the realm of group practice, they have less flexibility in controlling their time and their own schedules.”

If Anna Hare, MD, is any indication, younger dermatologists may buck this trend. The daughter of Dr. Rich in Portland, Dr. Hare joined her mother’s dermatology practice and research center knowing that she’d have “the respect and flexibility for deciding how I want to practice.”

Younger dermatologists, she said, place “more of an emphasis on work-life balance and quality of life.”

Fortunately, said Dr. Bergfeld, women have advanced enough in the ranks of dermatology that, in networking, in mentorship, and in workplace settings, attention can be paid more fully to discussions about work-life management – “how to manage your life when you’re working with family and kids and parents.”

In the 1970s, at the Cleveland Clinic, “there were only five women on staff and we were fighting for [basic] rights,” she said. “We wanted equality – we were [perceived as] little worker bees….We needed to climb as the men did to positions of leadership and address the problems of women.”

In pursuing their goals and making further progress, women dermatologists today should be “steady and calm,” she advised. Formally acquiring leadership skills and communication skills is a timeless need. And when there are biases or conflicts, “you cannot have righteous indignation, you cannot have revenge. You have to calm yourself and move forward.”

Wilma F. Bergfeld, MD, one of only five women in her medical school class of 1964 and the third female in her dermatology residency program, had recently been appointed as a junior clinical dermatologist and head of dermatopathology at the Cleveland Clinic when she was told by a superior that she would not be promoted or invited to serve on any committee or decision-making group.

“I was told I should go home at night and take care of my husband and two children,” she recalled of that moment in the 1970s. The comment made her feel “outraged,” and it drove her, calmly and steadily, to work harder and to “challenge the system.”

Dr. Bergfeld not only was elected to the Cleveland Clinic’s board of governors and board of trustees and served as president of the Clinic’s staff in 1990, she also became the first woman president of the American Academy of Dermatology (1992) and led numerous other dermatologic organizations. Much earlier on, in 1973, to help fulfill her vision of “women helping women,” she had also founded the Women’s Dermatologic Society (WDS). Three years earlier, in 1970, 6.9% of the approximately 4,000 dermatologists in the United States were women, according to the American Medical Association.

Today, when she goes to work as the long-time director of the Clinic’s dermatopathology fellowship and professor of dermatology and pathology at the Cleveland Clinic Educational Foundation, she sees a transformed staff and, more broadly, a national physician workforce in which women made up almost 50% of active dermatologists in 2017 and almost 60% of dermatology residents in 2018, according to data from the American Association of Medical Colleges.

It’s a different and better world, she and other women dermatologists said, but one in which women must continue to mentor other women and continue to challenge the system. Achieving work-life balance, fairer compensation, and a greater proportion of women in the higher ranks of academia are all on their work list.

Women’s impact on the specialty

Dr. Bergfeld and Molly Hinshaw, MD, the current president of the WDS, said they believe women are drawn to dermatology for its visual nature, the growth in diagnostic tests and therapies, and the opportunity to diagnose early and prevent progression of disease in patients of all ages. “It’s a small but mighty specialty,” said Dr. Hinshaw, associate professor of dermatology and section chief of dermatopathology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

It’s also a versatile specialty with a variety of subspecialties and niches to pursue – and women have been stepping in to fill unmet needs, Dr. Hinshaw said. “Women dermatologists are directing vulvar specialty clinics across the country, for example. There aren’t that many, but they’re filling an important niche. We have one at [our university] and it is packed.”

Women have also been drawn to the in-demand subspecialty of pediatric dermatology, she noted. They now make up more than two-thirds of all pediatric dermatologists, and many in practice have trained the old-fashioned way, completing two residencies. “That’s [involved] self-selection into an additional year of years training and a commitment to caring for special populations that, quite honestly, takes more time,” said Dr. Hinshaw, who, as part of her dermatology practice, runs a nail clinic at UW Health in Madison.

Amy S. Paller, MD, who chairs the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, where she is professor of dermatology and pediatrics and directs the Skin Biology & Diseases Resource-Based Center, is one of these women. She took a long and determined journey into the subspecialty, encountering bias and discouragement while actively seeking out mentors who helped her advance.

While in medical school at Stanford (Calif.) University in the late 1970s in a class “very progressively” made up of about one-third women, Dr. Paller met Alvin Jacobs, MD, who, in 1975, had founded the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “There wasn’t much pediatric dermatology in the world at the time, and it was Al who helped [me realize] that it combined my love of genetic research with my [desire] to work with children,” she recalled.

Per Dr. Jacob’s advice, she went to Northwestern to train in both pediatrics and dermatology under Nancy Esterly, MD, who “is considered by many to be the mother of pediatric dermatology.” And knowing that she wanted to do research, Dr. Paller also worked with Ruth Freinkel, MD, who “was the strongest bench researcher” at Northwestern. (Dr. Freinkel had been one of the first female dermatology residents at Harvard and was the first full-time faculty member in dermatology at Northwestern).

After completing postdoctoral research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Dr. Paller returned to Chicago and assumed Dr. Esterly’s position as chief of dermatology at the Children’s National Hospital of Chicago. It was there that “someone in a leadership position questioned me about how I could possibly be a scientist, a strong clinician, and a good mother to my three children – and suggested that I drop research,” Dr. Paller recalled.

“I think this person was trying to be helpful to me, but I was shocked,” she said. Just as Dr. Bergfeld had done, Dr. Paller channeled her frustration into new pursuits.

“It made me go home and think, how could I strengthen myself? What else could I do?” she said. “Soon after, with a highly supportive husband, I did a ‘pseudosabbatical,’ basically spending every ounce of spare time I had working with one of the premier female scientists in the country, Elaine Fuchs, and learning molecular biology” in her lab at the University of Chicago.

“I think we’ve all had discrimination along the way. Sometimes there’s implicit bias and sometimes there’s overt bias,” said Dr. Paller, who in 2004 led the society which her mentor Dr. Jacobs had founded several decades earlier. “I just jumped right in, and that’s enabled me to find good role models.”

Across dermatology broadly, the often holistic nature of the specialty – of the ability to peer into the body and its internal health – is another quality that women have been drawn to and advanced, Dr. Hinshaw said. “One of the reasons why I chose dermatology is because it’s a window to total patient health. Patients often see their dermatologists as physicians who help them identify next steps in their health care, who can help them address issues related to their overall health and well-being, including their mental health.”

In a WDS membership survey conducted in 2018, most respondents reported that they frequently or occasionally detect and diagnose systemic/internal diseases and conditions in their female patients, and that they consult and collaborate with different kinds of physicians (Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018 Nov 15;4[4]:189-92).

And in a March 2019 “Dialogues in Dermatology” podcast episode on the history and advancement of women in dermatology produced by the American Academy of Dermatology, Pearl Grimes, MD, a clinical professor of dermatology of the University of California, Los Angeles, and then-president of the WDS, described why “total women’s health” had become an additional focus for the society.

“We’re already gatekeepers” in many respects, Dr. Grimes said. “In addition to my addressing specific skin issues, my patients query me on hormone issues, on nutrition, on stress-related issues….and on [what other physicians they should see].”

Phoebe Rich, MD, who owns a small all-woman practice and a research center in Portland, Oregon, said that, in general, many women also communicate and practice in a way that facilitates holistic care. “These qualities aren’t exclusive to women, but women are very caring. We take time and are interested in [patients’] lives in general, not just their disease.”

Disparities in academia

Dermatology departments in academic medicine have burgeoned in size in the past 50 years, and women are well represented overall. In 2018, women comprised 51.2% of dermatology department faculty – up from 10.8% in 1970 – a current proportion that ranks fifth among specialties for the proportion of female faculty, according to a cross-sectional study of faculty diversity trends using data from the AAMC faculty roster (JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jan 8;156[3]:280-7).

The AAMC data show the share of women dermatology faculty declining at each subsequent rank, however – a finding that suggests that women are not promoted as quickly or to the same levels of leadership as men, the report’s authors noted. (Dermatology isn’t alone: The AAMC issued a call to action on gender equity in medicine this year, citing this inverse association.)

Another recently published study of gender trends in academic dermatology – this one looking at a smaller sample of data from 15 institutions – similarly found that women dermatologists made up a majority of faculty (53.6%) and were well represented as assistant professors (60.7%) but underrepresented as full professors (17%).

This study differed from the larger AAMC study, however, in that it controlled for “achievement indicators” – career duration, publications per year, and National Institutes of Health research funding – and found that gender alone was not associated with higher rank. Instead, promotions were correlated most significantly with NIH research funding and also with career duration and publications per year.

“If research achievement is to be used as a benchmark for academic promotion, increased efforts are needed to support the research activities of women,” the authors wrote, adding that recognition should be given to other factors as well.

Dr. Paller and Dr. Hinshaw both described the situation as complex and multifaceted. Some research on promotion in academia in general – but not all – has suggested that women do need to publish more than men in order to be promoted. But “the promotion process also has within it the ability to use judgment [about] the impact and merits of work,” said Dr. Hinshaw. “Not all publications [and levels of authorship] may be considered equal, for instance.”

Dr. Hinshaw said she is also concerned by data showing that women still perform the majority of household duties, “even in households in which both partners work outside the home equivalently.” As long as this is the case, women may be “inherently disadvantaged” in their ability to have adequate research time and to advance.

From where she sits, Dr. Paller sees several factors at play: “The pipeline, achievement during the pipeline, and decision-making about advancement” on the part of women themselves. Having served on search committees for top leadership in specialties in which women are well represented, she said, “I’ve seen fewer women who’ve come forward and been interested in rising into a chair or a dean position.”

And “having talked to so many women,” Dr. Paller added, “I think there’s a phenomenon where it’s harder for women to accept positions [that require] a significant change.”

Women “are nurturers, which makes them extremely good [leaders] and chairs, but it also makes it harder to make life changes that affect the people they love,” she said, noting that becoming a department chair or a dean often involves moving. “I also think that women in general are happier and committed to what they’re [currently] doing.”

Dr. Paller is optimistic that, with the support of department chairs and continued attention to role modeling and mentoring, the portrait of women in academic dermatology will continue to improve. Currently, 34 chairs of dermatology departments are female, she noted. “That number was 11 less 15 years ago.”

In the meantime, researchers are increasingly documenting trends in women’s editorships of journals as well as leadership and speaking opportunities at professional conferences.

The authors of one study published this year, for instance, reviewed the editorial boards of dermatology journals and found that women occupied 18% of editor in chief roles, 36% of deputy editor positions, and 22% of overall editorial board roles (Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Sep 12;6[1]:20-4). Other research shows women comprising 43% of all authorships across 23 dermatologic journals from 2008 to May 2017, 50.2% of first authorships, and 33.1% of last authorships (BMJ Open. 2018 Apr 13;8[4]:e020089).

Both in academic medicine and in practice, a gender pay gap still affects women physicians across the board. Medscape’s 2020 dermatologist compensation report shows male dermatologists earning about 12% more than their female peers (average, $435,000 vs. $387,000, respectively), while the average number of hours per week spent seeing patients is similar (36.2 vs. 35.6 hours, respectively).

And in its 2020 statement on gender equity, the AAMC said that women in academic medicine are offered less in starting salary, negotiated pay, and other forms of compensation than men “despite equal effort, rank, training, and experience.”

It’s complicated to tease apart all the factors that may be involved – but important to keep challenging the system, said Dr. Bergfeld, who was a long-time board adviser for Dermatology News. “I was underpaid,” she noted, and “this was only rectified in the last 10 years.”

Work-life balance

In the AAD podcast on women in dermatology, Dr. Grimes said that achieving a healthy and balanced work life remains one of the greatest challenges for women dermatologists – and it may be even greater than in the past given the growing numbers of group practices. “When women enter the realm of group practice, they have less flexibility in controlling their time and their own schedules.”

If Anna Hare, MD, is any indication, younger dermatologists may buck this trend. The daughter of Dr. Rich in Portland, Dr. Hare joined her mother’s dermatology practice and research center knowing that she’d have “the respect and flexibility for deciding how I want to practice.”

Younger dermatologists, she said, place “more of an emphasis on work-life balance and quality of life.”

Fortunately, said Dr. Bergfeld, women have advanced enough in the ranks of dermatology that, in networking, in mentorship, and in workplace settings, attention can be paid more fully to discussions about work-life management – “how to manage your life when you’re working with family and kids and parents.”

In the 1970s, at the Cleveland Clinic, “there were only five women on staff and we were fighting for [basic] rights,” she said. “We wanted equality – we were [perceived as] little worker bees….We needed to climb as the men did to positions of leadership and address the problems of women.”

In pursuing their goals and making further progress, women dermatologists today should be “steady and calm,” she advised. Formally acquiring leadership skills and communication skills is a timeless need. And when there are biases or conflicts, “you cannot have righteous indignation, you cannot have revenge. You have to calm yourself and move forward.”