User login

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Mrs. B, age 45, is referred by her primary care physician (PCP) for treatment of depressive symptoms that have worsened over the last 6 months. Her depressed mood is associated with worsening of multiple chronic, physical symptoms that began 4 years ago with several musculoskeletal complaints. Three years ago she developed recurrent abdominal discomfort and bloating, followed by recurrent chest pain. These symptoms have resulted in multiple trips to the hospital, several invasive procedures, and extensive medical consultation. After repeated workups, her symptoms are medically unexplained. These symptoms interfere with her ability to engage in and enjoy life.

Even after thorough investigation, up to one-third of patients’ physical symptoms remain unexplained.1-3 Most patients with unexplained symptoms improve; however, a small proportion do not. Such patients often are referred for psychiatric consultation.

Workup may reveal psychiatric etiology of a patient’s medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS). Clinicians need to take a unique approach to caring for patients whose symptoms remain unexplained after workup because diagnostic features may emerge over time and a collaborative, unbiased, integrated approach eventually may reveal a treatable diagnosis. This type of approach also is important when no medical or psychiatric diagnosis can be reached.

This article reviews the prevalence, comorbidity, and treatment challenges of patients whose physical symptoms are medically unexplained, and recommends evidence-based treatment strategies.

Inconsistent terminology

The terms MUPS, medically unexplained symptoms, somatoform disorder, somatization, and the functional syndromes (eg, irritable bowel syndrome [IBS], fibromyalgia, interstitial cystitis, chronic fatigue, etc.) often are used interchangeably. This inconsistent nomenclature creates classification difficulties because several of these terms assume a different etiology for the patient’s physical symptoms (ie, medical vs psychiatric).

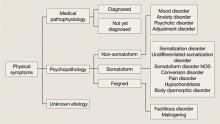

Physical symptoms typically are explained by:

- medical pathophysiology

- psychopathology, or

- unknown etiology (Figure).

MUPS typically are defined as physical or somatic symptoms without a known etiology after appropriate testing, workup, and referrals. Workup may be limited or extensive, may evolve over time (eg, diagnosis may be made 2 years after primary symptom onset), and often involves collaboration among several specialists.

The above definition does not specify severity, medical/psychiatric comorbidity, or number or duration of symptoms. A proposed classification, medically unexplained symptoms spectrum disorder, attempts to categorize patients with MUPS based on severity and duration of symptoms, as well as medical and/or psychiatric comorbidities (Table).4 MUPS may account for up to two-thirds of physical symptoms in specialty clinics; to read about the prevalence of MUPS, see the Box below.

Figure: Typical etiology of physical symptoms

NOS: Not otherwise specifiedTable

Medically unexplained symptoms spectrum disorder

| Severity | Mild, moderate, severe |

| Duration | Acute (days to weeks), subacute (<6 months), chronic (>6 months) |

| Comorbidity | Psychiatric, medical, none |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

CASE CONTINUED: Abuse and assault

Mrs. B has been married for 10 years and has 2 children. She denies using tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. Both of her parents were in good physical health. As a child Mrs. B was physically and verbally abused by her father, and her parents divorced when she was 15. She was sexually assaulted while in college.

Mrs. B has had 1 previous depressive episode, which occurred shortly after the sexual assault. During that time she was hospitalized twice for attempting suicide by overdosing on prescription medications. She was stabilized on fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, which was tapered and discontinued after 2 years.

Factors linked to MUPS

Young women (age 16 to 25) are more likely to receive an MUPS diagnosis than men or older individuals. Employment, socioeconomic background, and educational level are not consistently associated with MUPS.5 Patients with MUPS have higher rates of physical and sexual abuse.6

Several studies have shown an association with childhood parental ill health and development of MUPS, but the exact nature of “ill health” was not clearly defined. Parental death was not associated with MUPS, which suggests that the association to parental ill health is related to non-threatening physical disease.6

Approximately 60% of patients with MUPS have a comorbid non-somatoform DSM-IV-TR diagnosis.7-9 Symptoms and rates of depressive, anxiety, and panic disorders are higher in patients with MUPS than either healthy controls or patients with similar diseases of known organic pathology.7,8

The estimated prevalence of somatoform disorder in patients with MUPS is approximately 4%, which is higher than in the general population (.2% to 2%).7,8 On measures of mental and physical function, patients with MUPS who have somatoform disorders have been found to be more distressed than normal controls and patients with MUPS without somatoform disorders.8

Although few studies have directly examined the relationship between personality disorders and MUPS, there is evidence of an association between certain personality traits (eg, neuroticism, alexithymia, negative affect) and MUPS.10,11

CASE CONTINUED: Rejected advice

Mrs. B has been worked up multiple times for acute coronary syndrome; been unsuccessfully treated for gastroesophageal reflux disease, lactose intolerance, and IBS; had a negative rheumatologic workup; and tried several medication regimens with no improvement in symptoms. Three years ago Mrs. B’s gastroenterologist implied her abdominal symptoms were caused by her history of sexual assault and suggested she seek psychiatric consultation. Offended, Mrs. B sought a second opinion and no longer sees her first gastroenterologist.

Barriers to treatment

Despite having high levels of psychosocial distress, health care utilization, and medical disability, patients with MUPS often are suboptimally treated. Factors that might contribute to this include:

- inadequate identification

- bias in diagnosis and treatment

- poor follow-up on referrals

- an absence of treatment guidelines.7,12,13

Many clinicians are unaware of the high prevalence of MUPS, which often leads to repeated referral to specialty clinics, even when patients already have received an MUPS diagnosis.12,14 Additionally, clinicians often are unaware of how individual biases influence their diagnostic thought process. A “difficult patient” may receive a MUPS diagnosis more readily than a “pleasant patient,” which could contribute to an incomplete workup. An epidemiologic study revealed that the strongest predictor of misdiagnosing MUPS is doctor dissatisfaction with the clinical encounter.15 Younger, unmarried, anxious patients receiving disability benefits are more likely to be incorrectly labeled as having MUPS, only to later receive a non-MUPS diagnosis.15

Bias in treatment and intervention also exists. Qualitative analysis of consultations suggests that physicians’ decisions to offer patients somatic treatments (eg, investigation, add/change medications, referral to specialists) are responses to patients’ extended and complex accounts of their symptoms.17 The likelihood of intervention was unrelated to patients’ request for treatment, and intervention became less likely when patients described psychosocial problems.16

Patients with MUPS and comorbid psychiatric disorders often are referred for psychosocial treatment, but 1 study found that as few as 10% of such patients follow up on a referral.17 In that study, 81% of MUPS patients were willing to receive psychosocial treatment in a primary care setting by their physician. Although there are many reasons patients with MUPS resist referral to mental health professionals, be aware that many of these individuals do not attribute their symptoms to psychosocial problems or experience their symptoms psychologically. To these patients, psychiatric referral may seem inappropriate or be perceived as belittling and minimizing their symptoms.

CASE CONTINUED: Frustration and guilt

Mrs. B’s depressive symptoms began 18 months ago with fatigue, poor sleep, and withdrawal from her children and husband. She struggles with hopelessness that her physical symptoms will not resolve and guilt because of the financial strain her medical care has placed on the family. She is extremely frustrated that her doctors are unable to find a medical diagnosis for her symptoms and fears that without a diagnosis she will be perceived as “crazy.” She is not certain if there is a medical explanation for her symptoms but vehemently believes they are not associated with her mood or psychosocial stress.

Treatment strategies

A collaborative, unbiased, integrated approach to treatment can address some of the challenges that arise when patients with MUPS confront the limitations of modern medicine. Integrated care involves ongoing communication among medical and psychiatric specialists, as well as collaboration with social workers, physical therapists, nutritionists, or pain management specialists when indicated.

Although the primary care provider often coordinates a MUPS patient’s medical treatment, a consulting psychiatrist plays an important educational, diagnostic, and therapeutic role. The therapeutic role is especially important because patients with MUPS frequently view their general practitioner as having a limited role in managing psychosocial problems.18

Because physical illness and psychosocial stress frequently coexist and compound each other, diagnostic efforts should focus on medical and psychiatric illness. Review the patient’s medical workup of the unexplained symptoms and, when indicated, request further testing. Evaluate the risks and benefits of additional testing and discuss them with the patient; additional testing carries a risk of iatrogenic harm, higher false-positive rates, and increased costs. Avoiding iatrogenic harm and unnecessary, overly aggressive testing is essential.

Identifying primary or comorbid psychiatric disease and psychosocial issues also is integral to managing patients with MUPS. This may be difficult because some patients might be hesitant to discuss psychosocial issues, whereas others may be unaware of psychiatric symptomatology or the connection between mental and physical illness. When possible, it may be useful to clarify symptomatology as:

- primarily somatic (expression of psychological illness through physical means)

- primarily psychiatric (psychiatric illness presenting with physical symptoms) or

- bordering between somatic and psychiatric.

CASE CONTINUED: Collaboration and improvement

You diagnose Mrs. B with major depressive disorder and prescribe fluoxetine, titrating her up to 40 mg/d. Mrs. B also begins weekly psychodynamic psychotherapy. In collaboration with her PCP, you decide to refer Mrs. B to physical therapy and direct psychotherapy toward coping strategies, with the hope of improving functionality. Although she continues to have musculoskeletal symptoms after completing physical therapy, Mrs. B notices moderate improvement and feels less distressed by these symptoms.

After 1 year of fluoxetine treatment, Mrs. B’s depressive symptoms improve. In psychotherapy, her fixation on physical symptoms and desire to establish a diagnosis gradually lessen. As her emotional trauma from childhood abuse unravels, psychotherapy shifts toward improving affect regulation. During this time Mrs. B experiences an increase in unexplained chest pain and shortness of breath, which later abate.

Continued follow-up with a gastroenterologist leads to a diagnosis of celiac disease. With treatment, her GI symptoms resolve.

What do patients want?

Begin MUPS treatment by developing a supportive, empathic relationship with the patient. Carefully listen to the patient’s description of his or her symptoms. Elucidating patients’ experience often is challenging because their narratives frequently are complex, nonlinear, and limited by time.18 Patients’ models for understanding their symptoms also may be complex.18 They may be reluctant to share their explanations, fearing they will be unable to communicate the complexity of their beliefs or their symptoms will be oversimplified.18

Focus on understanding what the patient seeks from the physician—emotional support vs diagnosis vs treatment. In a prospective naturalistic study, the content of MUPS patients’ narratives was correlated with what they sought from their physician.17 Patients who sought emotional support frequently discussed psychosocial problems, issues, and management. Patients who wanted an explanation for their symptoms often mentioned physical symptoms, explanations, and diseases. Those who were looking for additional testing or intervention often directly addressed this with the physician.17

Although many patients desire a diagnosis and somatic treatment, this is not always their primary agenda. Many MUPS patients seek emotional support or confirmation of their explanatory model.17,18 Patients’ desires for emotional support, medical explanation, diagnosis, or somatic intervention often are neither clearly nor explicitly stated. Despite this, patients hope their physician understands the extent of their problems and value those who help them make sense of their narratives.18 Misunderstanding patients’ agendas can result in a mismatch of treatment expectations and fracture the patient-physician relationship. Developing mutual expectations is crucial to building rapport, improving collaborative care, and avoiding unnecessary, potentially harmful interventions.

Psychotherapic interventions

Psychopharmacologic treatment is indicated for MUPS patients who have comorbid psychiatric conditions.

Research of psychotherapy in MUPS has been plagued by methodologic problems and inconsistent results.3 Group therapy, short-term dynamic therapy, hypnotherapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have been studied. In a trial of 140 MUPS patients who received 1 session of CBT, 71% experienced improvement in physical symptoms, 47% in functional status, and 38% in measures of psychological distress.19 A review of 34 randomized controlled trials involving 3,922 patients with somatoform disorders who received CBT found that some patients with MUPS responded after 5 to 6 sessions.3

Cognitive techniques focus on identifying and restructuring automatic, dysfunctional thoughts that may compound, perpetuate, or worsen somatic symptoms. Behavioral techniques include relaxation and efforts to increase motivation. A CBT treatment plan may involve establishing goals, addressing patients’ understanding of their symptoms, obtaining a commitment for treatment, and negotiating the details of the treatment plan.8,12

Supportive techniques also are valuable in treating MUPS patients. Educate patients and treating physicians that there is a neurophysiologic basis for the patient’s physical symptoms and that symptoms may wax and wane. Reinforcement of functional improvement through concrete, practical solutions can help patients develop healthy, adaptive coping skills. Encouraging patients to move beyond somatic complaints to discuss social and personal difficulties can lead to more effective management of these problems.

Clearly communicate your initial impressions, diagnoses, and treatment plan to other members of the treatment team. A consultation letter from the psychiatrist to the PCP has been shown to decrease costs and slightly improve the patient’s functional status, symptoms, and quality of life.20 When possible, educate the PCP and specialists about the dynamics, challenges, biases, and frustrations physicians commonly face when caring for MUPS patients.

Related Resources

- Burton C. Beyond somatization: a review of the understanding and treatment of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Brit J Gen Pract. 2003;53:233-239.

- Creed F. The outcome of medically unexplained symptoms—will DSM-V improve on DSM-IV somatoform disorders? J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:379-381.

- Katon W, Sullivan M, Walker E. Medical symptoms without identified pathology: relationship to psychiatric disorders, childhood and adult trauma, and personality traits. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(9 Pt 2):917-925.

- Sharpe M, Mayou R, Walker J. Bodily symptoms: new approaches to classification. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60: 353-356.

Drug Brand Names

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) has been found to make up 10% to 30% of the physical symptoms in primary care clinics and 37% to 66% in specialty clinics.a-c The latter statistic is based on a cross-sectional survey of 899 consecutive new patients from 7 outpatient clinics in London, United Kingdom. Sixty-five percent responded and 52% of respondents had at least 1 medically unexplained symptom, diagnosed 3 months after initial clinic presentation.c

Patients with MUPS carry significant clinical importance. They are more likely to have a relatively poor quality of life and higher rates of disability.d,e They tend to be higher utilizers of health care.c,f High utilization of services and potentially unnecessary lab testing and consultation result in increased costs and high rates of iatrogenic complications.d-f

References

a. McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Bourgeois JA. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009.

b. Richardson RD, Engel CC. Evaluation and management of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Neurologist. 2004;10:18-30.

c. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms. An epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361-367.

d. Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford T, et al. Medically unexplained symptoms in frequent attenders of secondary health care: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2001;322:1-4.

e. Smith BJ, McGorn KJ, Weller D, et al. The identification in primary care of patients who have been repeatedly referred to hospital for medically unexplained symptoms: a pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:207-211.

f. Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478-489.

1. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Prevalence impact, and prognosis of multisomatoform disorder in primary care: a 5-year follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:430-434.

2. Jackson JL, George S, Hinchey S. Medically unexplained physical symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:540-542.

3. Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:881-888.

4. Smith RC, Dwamena FC. Classification and diagnosis of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:685-691.

5. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms. An epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361-367.

6. Hotopf M, Mayou R, Wadsworth M, et al. Childhood risk factors for adults with medically unexplained symptoms: results from a national birth cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(11):1796-1800.

7. Smith RC, Gardiner JC, Lyles JS, et al. Exploration of DSM-IV criteria in primary care patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:123-129.

8. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671-677.

9. Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms anxiety, and depression. A meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528-533.

10. Costa PT, McCrae RR. Neuroticism somatic complaints, and disease: is the bark worse than the bite? J Pers. 1987;55(2):299-315.

11. Gucht VD, Fischler B, Heiser W. Personality and affect as determinants of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. A follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:279-285.

12. Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478-489.

13. McFarlane AC, Ellis N, Fasphm F, et al. The conundrum of medically unexplained symptoms: questions to consider. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(5):369-377.

14. Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford T, et al. Medically unexplained symptoms in frequent attenders of secondary health care: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2001;322:1-4.

15. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: how often and why are they missed? QJM. 2000;93:21-28.

16. Salmon P, Humphris GM, Ring A, et al. Primary care consultations about medically unexplained symptoms: patient presentations and doctor responses that influence the probability of somatic intervention. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:571-577.

17. Salmon P, Ring A, Humphris GM, et al. Primary care consultations about medically unexplained symptoms: how do patients indicate what they want? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):450-456.

18. Peters S, Rogers A, Salmon P, et al. What do patients choose to tell their doctors? Qualitative analysis of potential barriers to reattributing medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;24(4):443-449.

19. Martin A, Rauh E, Fichter M, et al. A one-session treatment for patients suffering from medically unexplained symptoms in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:294-303.

20. Smith BJ, McGorn KJ, Weller D, et al. The identification in primary care of patients who have been repeatedly referred to hospital for medically unexplained symptoms: a pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:207-211.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Mrs. B, age 45, is referred by her primary care physician (PCP) for treatment of depressive symptoms that have worsened over the last 6 months. Her depressed mood is associated with worsening of multiple chronic, physical symptoms that began 4 years ago with several musculoskeletal complaints. Three years ago she developed recurrent abdominal discomfort and bloating, followed by recurrent chest pain. These symptoms have resulted in multiple trips to the hospital, several invasive procedures, and extensive medical consultation. After repeated workups, her symptoms are medically unexplained. These symptoms interfere with her ability to engage in and enjoy life.

Even after thorough investigation, up to one-third of patients’ physical symptoms remain unexplained.1-3 Most patients with unexplained symptoms improve; however, a small proportion do not. Such patients often are referred for psychiatric consultation.

Workup may reveal psychiatric etiology of a patient’s medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS). Clinicians need to take a unique approach to caring for patients whose symptoms remain unexplained after workup because diagnostic features may emerge over time and a collaborative, unbiased, integrated approach eventually may reveal a treatable diagnosis. This type of approach also is important when no medical or psychiatric diagnosis can be reached.

This article reviews the prevalence, comorbidity, and treatment challenges of patients whose physical symptoms are medically unexplained, and recommends evidence-based treatment strategies.

Inconsistent terminology

The terms MUPS, medically unexplained symptoms, somatoform disorder, somatization, and the functional syndromes (eg, irritable bowel syndrome [IBS], fibromyalgia, interstitial cystitis, chronic fatigue, etc.) often are used interchangeably. This inconsistent nomenclature creates classification difficulties because several of these terms assume a different etiology for the patient’s physical symptoms (ie, medical vs psychiatric).

Physical symptoms typically are explained by:

- medical pathophysiology

- psychopathology, or

- unknown etiology (Figure).

MUPS typically are defined as physical or somatic symptoms without a known etiology after appropriate testing, workup, and referrals. Workup may be limited or extensive, may evolve over time (eg, diagnosis may be made 2 years after primary symptom onset), and often involves collaboration among several specialists.

The above definition does not specify severity, medical/psychiatric comorbidity, or number or duration of symptoms. A proposed classification, medically unexplained symptoms spectrum disorder, attempts to categorize patients with MUPS based on severity and duration of symptoms, as well as medical and/or psychiatric comorbidities (Table).4 MUPS may account for up to two-thirds of physical symptoms in specialty clinics; to read about the prevalence of MUPS, see the Box below.

Figure: Typical etiology of physical symptoms

NOS: Not otherwise specifiedTable

Medically unexplained symptoms spectrum disorder

| Severity | Mild, moderate, severe |

| Duration | Acute (days to weeks), subacute (<6 months), chronic (>6 months) |

| Comorbidity | Psychiatric, medical, none |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

CASE CONTINUED: Abuse and assault

Mrs. B has been married for 10 years and has 2 children. She denies using tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. Both of her parents were in good physical health. As a child Mrs. B was physically and verbally abused by her father, and her parents divorced when she was 15. She was sexually assaulted while in college.

Mrs. B has had 1 previous depressive episode, which occurred shortly after the sexual assault. During that time she was hospitalized twice for attempting suicide by overdosing on prescription medications. She was stabilized on fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, which was tapered and discontinued after 2 years.

Factors linked to MUPS

Young women (age 16 to 25) are more likely to receive an MUPS diagnosis than men or older individuals. Employment, socioeconomic background, and educational level are not consistently associated with MUPS.5 Patients with MUPS have higher rates of physical and sexual abuse.6

Several studies have shown an association with childhood parental ill health and development of MUPS, but the exact nature of “ill health” was not clearly defined. Parental death was not associated with MUPS, which suggests that the association to parental ill health is related to non-threatening physical disease.6

Approximately 60% of patients with MUPS have a comorbid non-somatoform DSM-IV-TR diagnosis.7-9 Symptoms and rates of depressive, anxiety, and panic disorders are higher in patients with MUPS than either healthy controls or patients with similar diseases of known organic pathology.7,8

The estimated prevalence of somatoform disorder in patients with MUPS is approximately 4%, which is higher than in the general population (.2% to 2%).7,8 On measures of mental and physical function, patients with MUPS who have somatoform disorders have been found to be more distressed than normal controls and patients with MUPS without somatoform disorders.8

Although few studies have directly examined the relationship between personality disorders and MUPS, there is evidence of an association between certain personality traits (eg, neuroticism, alexithymia, negative affect) and MUPS.10,11

CASE CONTINUED: Rejected advice

Mrs. B has been worked up multiple times for acute coronary syndrome; been unsuccessfully treated for gastroesophageal reflux disease, lactose intolerance, and IBS; had a negative rheumatologic workup; and tried several medication regimens with no improvement in symptoms. Three years ago Mrs. B’s gastroenterologist implied her abdominal symptoms were caused by her history of sexual assault and suggested she seek psychiatric consultation. Offended, Mrs. B sought a second opinion and no longer sees her first gastroenterologist.

Barriers to treatment

Despite having high levels of psychosocial distress, health care utilization, and medical disability, patients with MUPS often are suboptimally treated. Factors that might contribute to this include:

- inadequate identification

- bias in diagnosis and treatment

- poor follow-up on referrals

- an absence of treatment guidelines.7,12,13

Many clinicians are unaware of the high prevalence of MUPS, which often leads to repeated referral to specialty clinics, even when patients already have received an MUPS diagnosis.12,14 Additionally, clinicians often are unaware of how individual biases influence their diagnostic thought process. A “difficult patient” may receive a MUPS diagnosis more readily than a “pleasant patient,” which could contribute to an incomplete workup. An epidemiologic study revealed that the strongest predictor of misdiagnosing MUPS is doctor dissatisfaction with the clinical encounter.15 Younger, unmarried, anxious patients receiving disability benefits are more likely to be incorrectly labeled as having MUPS, only to later receive a non-MUPS diagnosis.15

Bias in treatment and intervention also exists. Qualitative analysis of consultations suggests that physicians’ decisions to offer patients somatic treatments (eg, investigation, add/change medications, referral to specialists) are responses to patients’ extended and complex accounts of their symptoms.17 The likelihood of intervention was unrelated to patients’ request for treatment, and intervention became less likely when patients described psychosocial problems.16

Patients with MUPS and comorbid psychiatric disorders often are referred for psychosocial treatment, but 1 study found that as few as 10% of such patients follow up on a referral.17 In that study, 81% of MUPS patients were willing to receive psychosocial treatment in a primary care setting by their physician. Although there are many reasons patients with MUPS resist referral to mental health professionals, be aware that many of these individuals do not attribute their symptoms to psychosocial problems or experience their symptoms psychologically. To these patients, psychiatric referral may seem inappropriate or be perceived as belittling and minimizing their symptoms.

CASE CONTINUED: Frustration and guilt

Mrs. B’s depressive symptoms began 18 months ago with fatigue, poor sleep, and withdrawal from her children and husband. She struggles with hopelessness that her physical symptoms will not resolve and guilt because of the financial strain her medical care has placed on the family. She is extremely frustrated that her doctors are unable to find a medical diagnosis for her symptoms and fears that without a diagnosis she will be perceived as “crazy.” She is not certain if there is a medical explanation for her symptoms but vehemently believes they are not associated with her mood or psychosocial stress.

Treatment strategies

A collaborative, unbiased, integrated approach to treatment can address some of the challenges that arise when patients with MUPS confront the limitations of modern medicine. Integrated care involves ongoing communication among medical and psychiatric specialists, as well as collaboration with social workers, physical therapists, nutritionists, or pain management specialists when indicated.

Although the primary care provider often coordinates a MUPS patient’s medical treatment, a consulting psychiatrist plays an important educational, diagnostic, and therapeutic role. The therapeutic role is especially important because patients with MUPS frequently view their general practitioner as having a limited role in managing psychosocial problems.18

Because physical illness and psychosocial stress frequently coexist and compound each other, diagnostic efforts should focus on medical and psychiatric illness. Review the patient’s medical workup of the unexplained symptoms and, when indicated, request further testing. Evaluate the risks and benefits of additional testing and discuss them with the patient; additional testing carries a risk of iatrogenic harm, higher false-positive rates, and increased costs. Avoiding iatrogenic harm and unnecessary, overly aggressive testing is essential.

Identifying primary or comorbid psychiatric disease and psychosocial issues also is integral to managing patients with MUPS. This may be difficult because some patients might be hesitant to discuss psychosocial issues, whereas others may be unaware of psychiatric symptomatology or the connection between mental and physical illness. When possible, it may be useful to clarify symptomatology as:

- primarily somatic (expression of psychological illness through physical means)

- primarily psychiatric (psychiatric illness presenting with physical symptoms) or

- bordering between somatic and psychiatric.

CASE CONTINUED: Collaboration and improvement

You diagnose Mrs. B with major depressive disorder and prescribe fluoxetine, titrating her up to 40 mg/d. Mrs. B also begins weekly psychodynamic psychotherapy. In collaboration with her PCP, you decide to refer Mrs. B to physical therapy and direct psychotherapy toward coping strategies, with the hope of improving functionality. Although she continues to have musculoskeletal symptoms after completing physical therapy, Mrs. B notices moderate improvement and feels less distressed by these symptoms.

After 1 year of fluoxetine treatment, Mrs. B’s depressive symptoms improve. In psychotherapy, her fixation on physical symptoms and desire to establish a diagnosis gradually lessen. As her emotional trauma from childhood abuse unravels, psychotherapy shifts toward improving affect regulation. During this time Mrs. B experiences an increase in unexplained chest pain and shortness of breath, which later abate.

Continued follow-up with a gastroenterologist leads to a diagnosis of celiac disease. With treatment, her GI symptoms resolve.

What do patients want?

Begin MUPS treatment by developing a supportive, empathic relationship with the patient. Carefully listen to the patient’s description of his or her symptoms. Elucidating patients’ experience often is challenging because their narratives frequently are complex, nonlinear, and limited by time.18 Patients’ models for understanding their symptoms also may be complex.18 They may be reluctant to share their explanations, fearing they will be unable to communicate the complexity of their beliefs or their symptoms will be oversimplified.18

Focus on understanding what the patient seeks from the physician—emotional support vs diagnosis vs treatment. In a prospective naturalistic study, the content of MUPS patients’ narratives was correlated with what they sought from their physician.17 Patients who sought emotional support frequently discussed psychosocial problems, issues, and management. Patients who wanted an explanation for their symptoms often mentioned physical symptoms, explanations, and diseases. Those who were looking for additional testing or intervention often directly addressed this with the physician.17

Although many patients desire a diagnosis and somatic treatment, this is not always their primary agenda. Many MUPS patients seek emotional support or confirmation of their explanatory model.17,18 Patients’ desires for emotional support, medical explanation, diagnosis, or somatic intervention often are neither clearly nor explicitly stated. Despite this, patients hope their physician understands the extent of their problems and value those who help them make sense of their narratives.18 Misunderstanding patients’ agendas can result in a mismatch of treatment expectations and fracture the patient-physician relationship. Developing mutual expectations is crucial to building rapport, improving collaborative care, and avoiding unnecessary, potentially harmful interventions.

Psychotherapic interventions

Psychopharmacologic treatment is indicated for MUPS patients who have comorbid psychiatric conditions.

Research of psychotherapy in MUPS has been plagued by methodologic problems and inconsistent results.3 Group therapy, short-term dynamic therapy, hypnotherapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have been studied. In a trial of 140 MUPS patients who received 1 session of CBT, 71% experienced improvement in physical symptoms, 47% in functional status, and 38% in measures of psychological distress.19 A review of 34 randomized controlled trials involving 3,922 patients with somatoform disorders who received CBT found that some patients with MUPS responded after 5 to 6 sessions.3

Cognitive techniques focus on identifying and restructuring automatic, dysfunctional thoughts that may compound, perpetuate, or worsen somatic symptoms. Behavioral techniques include relaxation and efforts to increase motivation. A CBT treatment plan may involve establishing goals, addressing patients’ understanding of their symptoms, obtaining a commitment for treatment, and negotiating the details of the treatment plan.8,12

Supportive techniques also are valuable in treating MUPS patients. Educate patients and treating physicians that there is a neurophysiologic basis for the patient’s physical symptoms and that symptoms may wax and wane. Reinforcement of functional improvement through concrete, practical solutions can help patients develop healthy, adaptive coping skills. Encouraging patients to move beyond somatic complaints to discuss social and personal difficulties can lead to more effective management of these problems.

Clearly communicate your initial impressions, diagnoses, and treatment plan to other members of the treatment team. A consultation letter from the psychiatrist to the PCP has been shown to decrease costs and slightly improve the patient’s functional status, symptoms, and quality of life.20 When possible, educate the PCP and specialists about the dynamics, challenges, biases, and frustrations physicians commonly face when caring for MUPS patients.

Related Resources

- Burton C. Beyond somatization: a review of the understanding and treatment of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Brit J Gen Pract. 2003;53:233-239.

- Creed F. The outcome of medically unexplained symptoms—will DSM-V improve on DSM-IV somatoform disorders? J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:379-381.

- Katon W, Sullivan M, Walker E. Medical symptoms without identified pathology: relationship to psychiatric disorders, childhood and adult trauma, and personality traits. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(9 Pt 2):917-925.

- Sharpe M, Mayou R, Walker J. Bodily symptoms: new approaches to classification. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60: 353-356.

Drug Brand Names

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) has been found to make up 10% to 30% of the physical symptoms in primary care clinics and 37% to 66% in specialty clinics.a-c The latter statistic is based on a cross-sectional survey of 899 consecutive new patients from 7 outpatient clinics in London, United Kingdom. Sixty-five percent responded and 52% of respondents had at least 1 medically unexplained symptom, diagnosed 3 months after initial clinic presentation.c

Patients with MUPS carry significant clinical importance. They are more likely to have a relatively poor quality of life and higher rates of disability.d,e They tend to be higher utilizers of health care.c,f High utilization of services and potentially unnecessary lab testing and consultation result in increased costs and high rates of iatrogenic complications.d-f

References

a. McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Bourgeois JA. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009.

b. Richardson RD, Engel CC. Evaluation and management of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Neurologist. 2004;10:18-30.

c. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms. An epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361-367.

d. Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford T, et al. Medically unexplained symptoms in frequent attenders of secondary health care: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2001;322:1-4.

e. Smith BJ, McGorn KJ, Weller D, et al. The identification in primary care of patients who have been repeatedly referred to hospital for medically unexplained symptoms: a pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:207-211.

f. Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478-489.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Mrs. B, age 45, is referred by her primary care physician (PCP) for treatment of depressive symptoms that have worsened over the last 6 months. Her depressed mood is associated with worsening of multiple chronic, physical symptoms that began 4 years ago with several musculoskeletal complaints. Three years ago she developed recurrent abdominal discomfort and bloating, followed by recurrent chest pain. These symptoms have resulted in multiple trips to the hospital, several invasive procedures, and extensive medical consultation. After repeated workups, her symptoms are medically unexplained. These symptoms interfere with her ability to engage in and enjoy life.

Even after thorough investigation, up to one-third of patients’ physical symptoms remain unexplained.1-3 Most patients with unexplained symptoms improve; however, a small proportion do not. Such patients often are referred for psychiatric consultation.

Workup may reveal psychiatric etiology of a patient’s medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS). Clinicians need to take a unique approach to caring for patients whose symptoms remain unexplained after workup because diagnostic features may emerge over time and a collaborative, unbiased, integrated approach eventually may reveal a treatable diagnosis. This type of approach also is important when no medical or psychiatric diagnosis can be reached.

This article reviews the prevalence, comorbidity, and treatment challenges of patients whose physical symptoms are medically unexplained, and recommends evidence-based treatment strategies.

Inconsistent terminology

The terms MUPS, medically unexplained symptoms, somatoform disorder, somatization, and the functional syndromes (eg, irritable bowel syndrome [IBS], fibromyalgia, interstitial cystitis, chronic fatigue, etc.) often are used interchangeably. This inconsistent nomenclature creates classification difficulties because several of these terms assume a different etiology for the patient’s physical symptoms (ie, medical vs psychiatric).

Physical symptoms typically are explained by:

- medical pathophysiology

- psychopathology, or

- unknown etiology (Figure).

MUPS typically are defined as physical or somatic symptoms without a known etiology after appropriate testing, workup, and referrals. Workup may be limited or extensive, may evolve over time (eg, diagnosis may be made 2 years after primary symptom onset), and often involves collaboration among several specialists.

The above definition does not specify severity, medical/psychiatric comorbidity, or number or duration of symptoms. A proposed classification, medically unexplained symptoms spectrum disorder, attempts to categorize patients with MUPS based on severity and duration of symptoms, as well as medical and/or psychiatric comorbidities (Table).4 MUPS may account for up to two-thirds of physical symptoms in specialty clinics; to read about the prevalence of MUPS, see the Box below.

Figure: Typical etiology of physical symptoms

NOS: Not otherwise specifiedTable

Medically unexplained symptoms spectrum disorder

| Severity | Mild, moderate, severe |

| Duration | Acute (days to weeks), subacute (<6 months), chronic (>6 months) |

| Comorbidity | Psychiatric, medical, none |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

CASE CONTINUED: Abuse and assault

Mrs. B has been married for 10 years and has 2 children. She denies using tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. Both of her parents were in good physical health. As a child Mrs. B was physically and verbally abused by her father, and her parents divorced when she was 15. She was sexually assaulted while in college.

Mrs. B has had 1 previous depressive episode, which occurred shortly after the sexual assault. During that time she was hospitalized twice for attempting suicide by overdosing on prescription medications. She was stabilized on fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, which was tapered and discontinued after 2 years.

Factors linked to MUPS

Young women (age 16 to 25) are more likely to receive an MUPS diagnosis than men or older individuals. Employment, socioeconomic background, and educational level are not consistently associated with MUPS.5 Patients with MUPS have higher rates of physical and sexual abuse.6

Several studies have shown an association with childhood parental ill health and development of MUPS, but the exact nature of “ill health” was not clearly defined. Parental death was not associated with MUPS, which suggests that the association to parental ill health is related to non-threatening physical disease.6

Approximately 60% of patients with MUPS have a comorbid non-somatoform DSM-IV-TR diagnosis.7-9 Symptoms and rates of depressive, anxiety, and panic disorders are higher in patients with MUPS than either healthy controls or patients with similar diseases of known organic pathology.7,8

The estimated prevalence of somatoform disorder in patients with MUPS is approximately 4%, which is higher than in the general population (.2% to 2%).7,8 On measures of mental and physical function, patients with MUPS who have somatoform disorders have been found to be more distressed than normal controls and patients with MUPS without somatoform disorders.8

Although few studies have directly examined the relationship between personality disorders and MUPS, there is evidence of an association between certain personality traits (eg, neuroticism, alexithymia, negative affect) and MUPS.10,11

CASE CONTINUED: Rejected advice

Mrs. B has been worked up multiple times for acute coronary syndrome; been unsuccessfully treated for gastroesophageal reflux disease, lactose intolerance, and IBS; had a negative rheumatologic workup; and tried several medication regimens with no improvement in symptoms. Three years ago Mrs. B’s gastroenterologist implied her abdominal symptoms were caused by her history of sexual assault and suggested she seek psychiatric consultation. Offended, Mrs. B sought a second opinion and no longer sees her first gastroenterologist.

Barriers to treatment

Despite having high levels of psychosocial distress, health care utilization, and medical disability, patients with MUPS often are suboptimally treated. Factors that might contribute to this include:

- inadequate identification

- bias in diagnosis and treatment

- poor follow-up on referrals

- an absence of treatment guidelines.7,12,13

Many clinicians are unaware of the high prevalence of MUPS, which often leads to repeated referral to specialty clinics, even when patients already have received an MUPS diagnosis.12,14 Additionally, clinicians often are unaware of how individual biases influence their diagnostic thought process. A “difficult patient” may receive a MUPS diagnosis more readily than a “pleasant patient,” which could contribute to an incomplete workup. An epidemiologic study revealed that the strongest predictor of misdiagnosing MUPS is doctor dissatisfaction with the clinical encounter.15 Younger, unmarried, anxious patients receiving disability benefits are more likely to be incorrectly labeled as having MUPS, only to later receive a non-MUPS diagnosis.15

Bias in treatment and intervention also exists. Qualitative analysis of consultations suggests that physicians’ decisions to offer patients somatic treatments (eg, investigation, add/change medications, referral to specialists) are responses to patients’ extended and complex accounts of their symptoms.17 The likelihood of intervention was unrelated to patients’ request for treatment, and intervention became less likely when patients described psychosocial problems.16

Patients with MUPS and comorbid psychiatric disorders often are referred for psychosocial treatment, but 1 study found that as few as 10% of such patients follow up on a referral.17 In that study, 81% of MUPS patients were willing to receive psychosocial treatment in a primary care setting by their physician. Although there are many reasons patients with MUPS resist referral to mental health professionals, be aware that many of these individuals do not attribute their symptoms to psychosocial problems or experience their symptoms psychologically. To these patients, psychiatric referral may seem inappropriate or be perceived as belittling and minimizing their symptoms.

CASE CONTINUED: Frustration and guilt

Mrs. B’s depressive symptoms began 18 months ago with fatigue, poor sleep, and withdrawal from her children and husband. She struggles with hopelessness that her physical symptoms will not resolve and guilt because of the financial strain her medical care has placed on the family. She is extremely frustrated that her doctors are unable to find a medical diagnosis for her symptoms and fears that without a diagnosis she will be perceived as “crazy.” She is not certain if there is a medical explanation for her symptoms but vehemently believes they are not associated with her mood or psychosocial stress.

Treatment strategies

A collaborative, unbiased, integrated approach to treatment can address some of the challenges that arise when patients with MUPS confront the limitations of modern medicine. Integrated care involves ongoing communication among medical and psychiatric specialists, as well as collaboration with social workers, physical therapists, nutritionists, or pain management specialists when indicated.

Although the primary care provider often coordinates a MUPS patient’s medical treatment, a consulting psychiatrist plays an important educational, diagnostic, and therapeutic role. The therapeutic role is especially important because patients with MUPS frequently view their general practitioner as having a limited role in managing psychosocial problems.18

Because physical illness and psychosocial stress frequently coexist and compound each other, diagnostic efforts should focus on medical and psychiatric illness. Review the patient’s medical workup of the unexplained symptoms and, when indicated, request further testing. Evaluate the risks and benefits of additional testing and discuss them with the patient; additional testing carries a risk of iatrogenic harm, higher false-positive rates, and increased costs. Avoiding iatrogenic harm and unnecessary, overly aggressive testing is essential.

Identifying primary or comorbid psychiatric disease and psychosocial issues also is integral to managing patients with MUPS. This may be difficult because some patients might be hesitant to discuss psychosocial issues, whereas others may be unaware of psychiatric symptomatology or the connection between mental and physical illness. When possible, it may be useful to clarify symptomatology as:

- primarily somatic (expression of psychological illness through physical means)

- primarily psychiatric (psychiatric illness presenting with physical symptoms) or

- bordering between somatic and psychiatric.

CASE CONTINUED: Collaboration and improvement

You diagnose Mrs. B with major depressive disorder and prescribe fluoxetine, titrating her up to 40 mg/d. Mrs. B also begins weekly psychodynamic psychotherapy. In collaboration with her PCP, you decide to refer Mrs. B to physical therapy and direct psychotherapy toward coping strategies, with the hope of improving functionality. Although she continues to have musculoskeletal symptoms after completing physical therapy, Mrs. B notices moderate improvement and feels less distressed by these symptoms.

After 1 year of fluoxetine treatment, Mrs. B’s depressive symptoms improve. In psychotherapy, her fixation on physical symptoms and desire to establish a diagnosis gradually lessen. As her emotional trauma from childhood abuse unravels, psychotherapy shifts toward improving affect regulation. During this time Mrs. B experiences an increase in unexplained chest pain and shortness of breath, which later abate.

Continued follow-up with a gastroenterologist leads to a diagnosis of celiac disease. With treatment, her GI symptoms resolve.

What do patients want?

Begin MUPS treatment by developing a supportive, empathic relationship with the patient. Carefully listen to the patient’s description of his or her symptoms. Elucidating patients’ experience often is challenging because their narratives frequently are complex, nonlinear, and limited by time.18 Patients’ models for understanding their symptoms also may be complex.18 They may be reluctant to share their explanations, fearing they will be unable to communicate the complexity of their beliefs or their symptoms will be oversimplified.18

Focus on understanding what the patient seeks from the physician—emotional support vs diagnosis vs treatment. In a prospective naturalistic study, the content of MUPS patients’ narratives was correlated with what they sought from their physician.17 Patients who sought emotional support frequently discussed psychosocial problems, issues, and management. Patients who wanted an explanation for their symptoms often mentioned physical symptoms, explanations, and diseases. Those who were looking for additional testing or intervention often directly addressed this with the physician.17

Although many patients desire a diagnosis and somatic treatment, this is not always their primary agenda. Many MUPS patients seek emotional support or confirmation of their explanatory model.17,18 Patients’ desires for emotional support, medical explanation, diagnosis, or somatic intervention often are neither clearly nor explicitly stated. Despite this, patients hope their physician understands the extent of their problems and value those who help them make sense of their narratives.18 Misunderstanding patients’ agendas can result in a mismatch of treatment expectations and fracture the patient-physician relationship. Developing mutual expectations is crucial to building rapport, improving collaborative care, and avoiding unnecessary, potentially harmful interventions.

Psychotherapic interventions

Psychopharmacologic treatment is indicated for MUPS patients who have comorbid psychiatric conditions.

Research of psychotherapy in MUPS has been plagued by methodologic problems and inconsistent results.3 Group therapy, short-term dynamic therapy, hypnotherapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have been studied. In a trial of 140 MUPS patients who received 1 session of CBT, 71% experienced improvement in physical symptoms, 47% in functional status, and 38% in measures of psychological distress.19 A review of 34 randomized controlled trials involving 3,922 patients with somatoform disorders who received CBT found that some patients with MUPS responded after 5 to 6 sessions.3

Cognitive techniques focus on identifying and restructuring automatic, dysfunctional thoughts that may compound, perpetuate, or worsen somatic symptoms. Behavioral techniques include relaxation and efforts to increase motivation. A CBT treatment plan may involve establishing goals, addressing patients’ understanding of their symptoms, obtaining a commitment for treatment, and negotiating the details of the treatment plan.8,12

Supportive techniques also are valuable in treating MUPS patients. Educate patients and treating physicians that there is a neurophysiologic basis for the patient’s physical symptoms and that symptoms may wax and wane. Reinforcement of functional improvement through concrete, practical solutions can help patients develop healthy, adaptive coping skills. Encouraging patients to move beyond somatic complaints to discuss social and personal difficulties can lead to more effective management of these problems.

Clearly communicate your initial impressions, diagnoses, and treatment plan to other members of the treatment team. A consultation letter from the psychiatrist to the PCP has been shown to decrease costs and slightly improve the patient’s functional status, symptoms, and quality of life.20 When possible, educate the PCP and specialists about the dynamics, challenges, biases, and frustrations physicians commonly face when caring for MUPS patients.

Related Resources

- Burton C. Beyond somatization: a review of the understanding and treatment of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Brit J Gen Pract. 2003;53:233-239.

- Creed F. The outcome of medically unexplained symptoms—will DSM-V improve on DSM-IV somatoform disorders? J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:379-381.

- Katon W, Sullivan M, Walker E. Medical symptoms without identified pathology: relationship to psychiatric disorders, childhood and adult trauma, and personality traits. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(9 Pt 2):917-925.

- Sharpe M, Mayou R, Walker J. Bodily symptoms: new approaches to classification. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60: 353-356.

Drug Brand Names

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) has been found to make up 10% to 30% of the physical symptoms in primary care clinics and 37% to 66% in specialty clinics.a-c The latter statistic is based on a cross-sectional survey of 899 consecutive new patients from 7 outpatient clinics in London, United Kingdom. Sixty-five percent responded and 52% of respondents had at least 1 medically unexplained symptom, diagnosed 3 months after initial clinic presentation.c

Patients with MUPS carry significant clinical importance. They are more likely to have a relatively poor quality of life and higher rates of disability.d,e They tend to be higher utilizers of health care.c,f High utilization of services and potentially unnecessary lab testing and consultation result in increased costs and high rates of iatrogenic complications.d-f

References

a. McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Bourgeois JA. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009.

b. Richardson RD, Engel CC. Evaluation and management of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Neurologist. 2004;10:18-30.

c. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms. An epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361-367.

d. Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford T, et al. Medically unexplained symptoms in frequent attenders of secondary health care: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2001;322:1-4.

e. Smith BJ, McGorn KJ, Weller D, et al. The identification in primary care of patients who have been repeatedly referred to hospital for medically unexplained symptoms: a pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:207-211.

f. Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478-489.

1. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Prevalence impact, and prognosis of multisomatoform disorder in primary care: a 5-year follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:430-434.

2. Jackson JL, George S, Hinchey S. Medically unexplained physical symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:540-542.

3. Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:881-888.

4. Smith RC, Dwamena FC. Classification and diagnosis of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:685-691.

5. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms. An epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361-367.

6. Hotopf M, Mayou R, Wadsworth M, et al. Childhood risk factors for adults with medically unexplained symptoms: results from a national birth cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(11):1796-1800.

7. Smith RC, Gardiner JC, Lyles JS, et al. Exploration of DSM-IV criteria in primary care patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:123-129.

8. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671-677.

9. Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms anxiety, and depression. A meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528-533.

10. Costa PT, McCrae RR. Neuroticism somatic complaints, and disease: is the bark worse than the bite? J Pers. 1987;55(2):299-315.

11. Gucht VD, Fischler B, Heiser W. Personality and affect as determinants of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. A follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:279-285.

12. Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478-489.

13. McFarlane AC, Ellis N, Fasphm F, et al. The conundrum of medically unexplained symptoms: questions to consider. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(5):369-377.

14. Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford T, et al. Medically unexplained symptoms in frequent attenders of secondary health care: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2001;322:1-4.

15. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: how often and why are they missed? QJM. 2000;93:21-28.

16. Salmon P, Humphris GM, Ring A, et al. Primary care consultations about medically unexplained symptoms: patient presentations and doctor responses that influence the probability of somatic intervention. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:571-577.

17. Salmon P, Ring A, Humphris GM, et al. Primary care consultations about medically unexplained symptoms: how do patients indicate what they want? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):450-456.

18. Peters S, Rogers A, Salmon P, et al. What do patients choose to tell their doctors? Qualitative analysis of potential barriers to reattributing medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;24(4):443-449.

19. Martin A, Rauh E, Fichter M, et al. A one-session treatment for patients suffering from medically unexplained symptoms in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:294-303.

20. Smith BJ, McGorn KJ, Weller D, et al. The identification in primary care of patients who have been repeatedly referred to hospital for medically unexplained symptoms: a pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:207-211.

1. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Prevalence impact, and prognosis of multisomatoform disorder in primary care: a 5-year follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:430-434.

2. Jackson JL, George S, Hinchey S. Medically unexplained physical symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:540-542.

3. Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:881-888.

4. Smith RC, Dwamena FC. Classification and diagnosis of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:685-691.

5. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms. An epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361-367.

6. Hotopf M, Mayou R, Wadsworth M, et al. Childhood risk factors for adults with medically unexplained symptoms: results from a national birth cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(11):1796-1800.

7. Smith RC, Gardiner JC, Lyles JS, et al. Exploration of DSM-IV criteria in primary care patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:123-129.

8. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671-677.

9. Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms anxiety, and depression. A meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528-533.

10. Costa PT, McCrae RR. Neuroticism somatic complaints, and disease: is the bark worse than the bite? J Pers. 1987;55(2):299-315.

11. Gucht VD, Fischler B, Heiser W. Personality and affect as determinants of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. A follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:279-285.

12. Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478-489.

13. McFarlane AC, Ellis N, Fasphm F, et al. The conundrum of medically unexplained symptoms: questions to consider. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(5):369-377.

14. Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford T, et al. Medically unexplained symptoms in frequent attenders of secondary health care: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2001;322:1-4.

15. Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: how often and why are they missed? QJM. 2000;93:21-28.

16. Salmon P, Humphris GM, Ring A, et al. Primary care consultations about medically unexplained symptoms: patient presentations and doctor responses that influence the probability of somatic intervention. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:571-577.

17. Salmon P, Ring A, Humphris GM, et al. Primary care consultations about medically unexplained symptoms: how do patients indicate what they want? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):450-456.

18. Peters S, Rogers A, Salmon P, et al. What do patients choose to tell their doctors? Qualitative analysis of potential barriers to reattributing medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;24(4):443-449.

19. Martin A, Rauh E, Fichter M, et al. A one-session treatment for patients suffering from medically unexplained symptoms in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:294-303.

20. Smith BJ, McGorn KJ, Weller D, et al. The identification in primary care of patients who have been repeatedly referred to hospital for medically unexplained symptoms: a pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:207-211.