User login

If this is a typical audience of physicians involved in perioperative care, about 35% to 40% of you have been sued for malpractice and have learned the hard way some of the lessons we will discuss today. This session will begin with an overview of malpractice law and medicolegal principles, after which we will review three real-life malpractice cases and open the floor to the audience for discussion of the lessons these cases can offer.

MALPRACTICE LAWSUITS ARE COMMON, EXPENSIVE, DAMAGING

If a physician practices long enough, lawsuits are nearly inevitable, especially in certain specialties. Surgeons and anesthesiologists are sued about once every 4 to 5 years; internists generally are sued less, averaging once every 7 to 10 years,1 but hospitalists and others who practice a good deal of perioperative care probably constitute a higher risk pool among internists.

At the same time, it is estimated that only one in eight preventable medical errors committed in hospitals results in a malpractice claim.2 From 1995 to 2000, the number of new malpractice claims actually declined by approximately 4%.3

Jury awards can be huge

Fewer than half (42%) of verdicts in malpractice cases are won by plaintiffs.4 But when plaintiffs succeed, the awards can be costly: the mean amount of physician malpractice payments in the United States in 2006 (the most recent data available) was $311,965, according to the National Practitioner Data Bank.5 Cases that involve a death result in substantially higher payments, averaging $1.4 million.4

Lawsuits are traumatic

Even if a physician is covered by good malpractice insurance, a malpractice lawsuit typically changes his or her life. It causes major disruption to the physician’s practice and may damage his or her reputation. Lawsuits cause considerable emotional distress, including a loss of self-esteem, particularly if the physician feels that a mistake was made in the delivery of care.

CATEGORIES OF CLAIMS IN MALPRACTICE LAW

Malpractice law involves torts, which are civil wrongs causing injury to a person or property for which the plaintiff may seek redress through the courts. In general, the plaintiff seeks financial compensation. Practitioners do not go to jail for committing malpractice unless a district attorney decides that the harm was committed intentionally, in which case criminal charges may be brought.

There are many different categories of claims in malpractice law. The most common pertaining to perioperative medicine involve issues surrounding informed consent and medical negligence (the worst form being wrongful death).

Informed consent

Although everyone is familiar with informed consent, details of the process are called into question when something goes wrong. Informed consent is based on the right of patient autonomy: each person has a right to determine what will be done to his or her body, which includes the right to consent to or refuse treatment.

For any procedure, treatment, or medication, patients should be informed about the following:

- The nature of the intervention

- The benefits of the intervention (why it is being recommended)

- Significant risks reasonably expected to exist

- Available alternatives (including “no treatment”).

If possible, it is important that the patient’s family understand the risks involved, because if the patient dies or becomes incapacitated, a family that is surprised by the outcome is more likely to sue.

The standard to which physicians are held in malpractice suits is that of a “reasonable physician” dealing with a “reasonable patient.” Often, a plaintiff claims that he or she did not know that a specific risk was involved, and the doctor claims that he or she spent a “typical” amount of time explaining all the risks. If that amount of time was only a few seconds, that may not pass the “reasonable physician” test, as a jury might conclude that more time may have been necessary.

Negligence and wrongful death

Negligence, including wrongful death, is a very common category of claim. The plaintiff generally must demonstrate four elements in negligence claims:

- The provider had a duty to the patient

- The duty was breached

- An injury occurred

- The breach of duty was a “proximate cause” of the injury.

Duty arises from the physician-patient relationship: any person whose name is on the medical chart essentially has a duty to the patient and can be brought into the case, even if the involvement was only peripheral.

Breach of duty. Determining whether a breach of duty occurred often involves a battle of medical experts. The standard of care is defined as what a reasonable practitioner would do under the same or similar circumstances, assuming similar training and background. The jury decides whether the physician met the standard of care based on testimony from experts.

The Latin phrase res ipsa loquitur means “the thing speaks for itself.” In surgery, the classic example is if an instrument or a towel were accidentally left in a patient. In such a situation, the breach of duty is obvious, so the strategy of the defense generally must be to show that the patient was not harmed by the breach.

Injury. The concept of injury can be broad and often depends on distinguishing bad practice from a bad or unfortunate outcome. For instance, a patient who suffered multisystem trauma but whose life was saved by medical intervention could sue if he ended up with paresthesia in the foot afterwards. An expert may be called to help determine whether or not the complication is reasonable for the particular medical situation. Patient expectations usually factor prominently into questions of injury.

Proximate cause often enters into situations involving wrongful death. A clear understanding of the cause of death or evidence from an autopsy is not necessarily required for a plaintiff to argue that malpractice was a proximate cause of death. A plaintiff’s attorney will often speculate why a patient died, and because the plaintiff’s burden of proof is so low (see next paragraph), it may not help the defense to argue that it is pure speculation that a particular event was related to the death.

A low burden of proof

In a civil tort, the burden of proof is established by a “preponderance of the evidence,” meaning that the allegation is “more likely than not.” This is a much lower standard than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” threshold used for criminal proceedings. In other words, the plaintiff has to show only that the chance that malpractice occurred was greater than 50%.

Three types of damages

Potential damages (financial compensation) in malpractice suits fall into three categories:

- Economic, or the monetary costs of an injury (eg, medical bills or loss of income)

- Noneconomic (eg, pain and suffering, loss of ability to have sex)

- Punitive, or damages to punish a defendant for willful and wanton conduct.

Punitive damages are generally not covered by malpractice insurance policies and are only rarely involved in cases against an individual physician. They are more often awarded when deep pockets are perceived to be involved, such as in a case against a hospital system or an insurance company, and when the jury wants to punish the entity for doing something that was believed to be willful.

REDUCING THE RISK OF BEING SUED

Regardless of the circumstances, communication is probably the most important factor determining whether a physician will be sued. Sometimes a doctor does everything right medically but gets sued because of lack of communication with the patient. Conversely, many of us know of veteran physicians who still practice medicine as they did 35 years ago but are never sued because they have a great rapport with their patients and their patients love them for it.

The importance of careful charting also cannot be overemphasized. In malpractice cases, experts for the plaintiff will comb through the medical records and be sure to notice if something is missing. The plaintiff also benefits enormously if, for instance, nurses documented that they paged the doctor many times over a 3-day period and got no response.

CASE 1: PATIENT DIES DURING PREOPERATIVE STRESS TEST FOR KNEE SURGERY

A 65-year-old man with New York Heart Association class III cardiac disease (marked limitation of physical activity) is scheduled for a total knee arthroplasty and is seen at the preoperative testing center. His past medical history includes coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and prior repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. He is referred for a preoperative stress test.

Dobutamine stress echocardiography is performed. His target heart rate is reached at 132 beats per minute with sporadic premature ventricular contractions. Toward the end of the test, he complains of shortness of breath and chest pain. The test is terminated, and the patient goes into ventricular tachycardia and then ventricular fibrillation. Despite resuscitative efforts, he dies.

Dr. Michota: From the family’s perspective, this patient had come for quality-of-life–enhancing surgery. They were looking forward to him getting a new knee so he could play golf again when he retired. The doctor convinced them that he needed a stress test first, which ends up killing him. Mr. Donnelly, as a lawyer, would you want to be the plaintiff’s attorney in this case?

Mr. Donnelly: Very much so. The family never contemplated that their loved one would die from this procedure. The first issue would be whether or not the possibility of complications or death from the stress test had been discussed with the patient or his family.

Consent must be truly ‘informed’ and documented

Dr. Michota: How many of our audience members who do preoperative assessments and refer patients for stress testing can recall a conversation with a patient that included the comment, “You may die from getting this test”? Before this case occurred, I never brought up this possibility, but I do now. This case illustrates how important expectations are.

Comment from the audience: I think you have to be careful of your own bias about risks. You might say to the patient, “There’s a risk that you’ll have an arrhythmia and die,” but if you also tell him, “I’ve never seen that happen during a stress test in my 10 years of practice,” you’ve biased the informed consent. The family can say, “Well, he basically told us that it wasn’t going to happen; he’d never seen a case of it.”

Dr. Michota: Are there certain things we shouldn’t say? Surely you should never promise somebody a good outcome by saying that certain rare events never happen.

Mr. Donnelly: That’s true. You can give percentages. You might say, “I’m letting you know there’s a possibility that you could die from this, but it’s a low percentage risk.” That way, you are informing the patient. This relates to the “reasonable physician” and “reasonable patient” standard. You are expected to do what is reasonable.

Is a signed consent form adequate defense?

Dr. Michota: What should the defense team do now? Let’s say informed consent was obtained and documented at the stress lab. The patient signed a form that listed death as a risk, but no family members were present. Is this an adequate defense?

Mr. Donnelly: It depends on whether the patient understood what was on the form and had the opportunity to ask questions.

Dr. Michota: So the form means nothing?

Mr. Donnelly: If he didn’t understand it, that is correct.

Dr. Michota: We thought he understood it. Can’t we just say, “Of course he understood it—he signed it.”

Mr. Donnelly: No. Keep in mind that most jurors have been patients at one time or another. There may be a perception that physicians are rushed or don’t have time to answer questions. Communication is really important here.

Dr. Michota: But surely there’s a physician on the jury who can help talk to the other jurors about how it really works.

Mr. Donnelly: No, a “jury of peers” is not a jury box of physicians. The plaintiff’s attorneys tend to exclude scientists and other educated professionals from the jury; they don’t want jurors who are accustomed to holding people to certain standards. They prefer young, impressionable people who wouldn’t think twice about awarding somebody $20 million.

Who should be obtaining informed consent?

Question from the audience: Who should have obtained informed consent for this patient—the doctor who referred him for the stress test or the cardiologist who conducted the test? Sometimes I have to get informed consent for specialty procedures that I myself do not understand very well. Could I be considered culpable even though I’m not the one doing the procedure? I can imagine an attorney asking, “Doctor, are you a cardiologist? How many of these tests do you do? Why are you the one doing the informed consent? Did the patient really understand the effects of the test? Do you really understand them?”

Dr. Michota: That question is even more pertinent if the patient is referred to another institution covered under different malpractice insurance. You can bet the other provider will try to blame you if something goes wrong.

Mr. Donnelly: In an ideal world, both the referring physician and the physician who does the test discuss the risks, benefits, and alternatives, and answer all questions that the patient and family have. The discussion is properly documented in the medical record.

Question from the audience: Can you address the issue of supervision? What is the liability of a resident or intern in doing the informed consent?

Mr. Donnelly: The attending physician is usually responsible for everything that a resident does. I would prefer that the attending obtain the informed consent.

Dr. Michota: But our fellows and second-year postgraduate residents are independent licensed practitioners in Ohio. Does letting them handle informed consent pose a danger to a defense team’s legal case?

Mr. Donnelly: It’s not necessarily a danger medically, but it gives the plaintiff something to talk about. They will ignore the fact that an independent licensed practitioner obtained the informed consent. They will simply focus on the fact that the physician was a resident or fellow. They will claim, “They had this young, inexperienced doctor give the informed consent when there were staff physicians with 20 years of experience who should have done it.” Plaintiffs will attempt to get a lot of mileage out of these minor issues.

Question from the audience: At our institution, the physician is present with the technician, so that when the physician obtains consent, the technician signs as a witness. The bottom of the long form basically says, “By signing this form, I attest that the physician performing the test has informed me of the benefits and risks of this test, and I agree to go ahead. I fully understand the implications of the test.” Does that have value in the eyes of the law?

Mr. Donnelly: That’s a great informed consent process and will have great value. That said, you can still get sued, because you can get sued for anything. But the jury ultimately decides, and odds are that with a process like yours they will conclude that the patient knew all the risks and benefits and alternatives because he or she signed the form and the doctor documented that everything was discussed.

Confidentiality vs family involvement

Comment from the audience: I’m struck by the comments that informed consent is supposed to be with the family so that there will be living witnesses in case the patient dies. According to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations, we have to be very careful to maintain confidentiality. For a competent patient, medical discussions are private unless specific permission has been obtained to involve the family.

Mr. Donnelly: Yes, we’ve assumed that the patient gave permission to discuss these issues with his family. If the patient does not want that, obviously you can’t include the family because of HIPAA regulations.

Question from the audience: Should we routinely ask a patient to involve the family in an informed consent in case something goes wrong?

Mr. Donnelly: No. In general, it’s appropriate only if the family is already present.

Dr. Michota: Keep in mind that there’s nothing you can do to completely prevent being sued. You can do everything right and still get sued. If you’re following good clinical practice and a patient doesn’t want to involve the family, all you can do is document your discussion and that you believed the patient understood the risks of the procedure.

Question from the audience: Do you consider a patient’s decision-making capacity for informed consent? Should physicians document it prior to obtaining consent? A plaintiff can always claim that an elderly patient did not understand.

Mr. Donnelly: I have never seen specific documentation that a patient had capacity to consent, but it’s a good idea for a borderline case. For such a case, it’s especially important to involve the family and document, “I discussed the matter with this elderly patient and her husband and three daughters.” You could also get a psychiatric consult or a social worker to help determine whether a patient has the capacity to make legal and medical decisions.

CASE 2: FATAL POSTSURGICAL MI RAISES QUESTIONS ABOUT THE PREOP EVALUATION

A 75-year-old man with rectal cancer presents for colorectal surgery. He has a remote cardiac history but exercises regularly and has a good functional classification without symptoms. The surgery is uneventful, but the patient develops hypotension in the postanesthesia care unit. He improves the next morning and goes to the colorectal surgery ward. Internal bleeding occurs but initially goes unrecognized; on postoperative day 2, his hemoglobin is found to be 2 g/dL and he is transferred to the intensive care unit, then back to the operating room, where he suffers cardiac arrest. He is revived but dies 2 weeks later. Autopsy reveals that he died of a myocardial infarction (MI).

Dr. Michota: The complaint in this case is that the patient did not receive a proper preoperative evaluation because no cardiac workup was done. As the hypothetical defense attorney, do you feel this case has merit? The patient most likely had an MI from demand ischemia due to hemorrhage, but does this have anything to do with not having a cardiac workup?

Mr. Donnelly: You as the physician are saying that even if he had an electrocardiogram (ECG), it is likely that nothing would have been determined. The cardiac problems he had prior to the surgery in question were well controlled, occurred in the distant past, and may not have affected the outcome. Maybe his remote cardiac problems were irrelevant and something else caused the MI that killed him. Nevertheless, the fact that the ECG wasn’t done still could be a major issue for the plaintiff’s attorney. After the fact, it seems like a no-brainer that an ECG should have been done in a case like this, and it’s easy for the plaintiff to argue that it might have detected something. The defense has to keep reminding the jury that the case cannot be looked at retrospectively, and that’s a tall order.

Dr. Michota: This case shows that even in the context of high-quality care, such things can happen. We have spent a lot of time at this summit talking about guidelines. But at the end of the day, if somebody dies perioperatively of an MI, the family may start looking for blame and any plaintiff’s attorney will go through the record to see if a preoperative ECG was done. If it wasn’t, a suit will get filed.

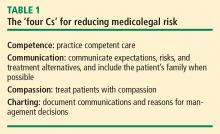

The four Cs offer the best protection

Question from the audience: Even if the physician had done the ECG, how do you know the plaintiff’s attorney wouldn’t attack him for not ordering a stress test? And if he had done a stress test, then they’d ask why he didn’t order a catheterization. Where is it going to end?

Dr. Michota: You make a good point. The best way for physicians to protect themselves is to follow the four Cs mentioned earlier: competent care, communication, compassion, and charting. After I learned about this case, the next time I was in the clinic and didn’t order an ECG, I asked the patient, “Did you expect that we would do an ECG here today?” When he responded that he did, I talked to him about how it wasn’t indicated and probably would not change management. So that level of communication can sometimes prevent a lawsuit that might stem from a patient not feeling informed. I’m not suggesting that you spend hours explaining details with each patient, but it’s good to be aware that cases like this happen and how you can reduce their likelihood.

Battles of the experts

Question from the audience: Exactly what standard is applied when the “standard of care” is determined in a court? For instance, my hospital may routinely order stress tests, whereas the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines are more restrictive in recommending when a stress test is indicated. Which standard would apply in court?

Dr. Michota: It’s easy to find a plaintiff’s expert who will say just about anything. If you claim that everybody gets a stress test at your community hospital and a patient dies during the stress test, the plaintiff’s team will find an expert to say, “That was an unnecessary test and posed an unnecessary risk.” If you’re in a setting where stress tests are rarely done for preoperative evaluation, they’ll find an expert to say, “Stress testing was available; it should have been done.”

This is when the battles of the experts occur. If you have a superstar physician on your defense team, the plaintiff will have to find someone of equal pedigree who can argue against him or her. Sometimes cases go away because the defense lines up amazing experts and the plaintiffs lose their stomach for the money it would take to bring the case forward. But usually cases do not involve that caliber of experts; most notables in the field are academic physicians who don’t do this type of work. Usually you get busy physicians who spend 75% of their time in clinical practice and seem smart enough to impress the jury. Although they can say things that aren’t even factual, they can sway the jury.

Question from the audience: I would not have ordered a preoperative ECG on this healthy 75-year-old, but one of the experts at this summit said that he would get a baseline ECG for such a case. How are differences like these reconciled in the legal context?

Dr. Michota: The standard to which we are held is that of a reasonable physician. Can you show that your approach was a reasonable one? Can you say, “I didn’t order the ECG for the following reasons, and I discussed the issue with the patient”? Or alternately, “An ECG was ordered for the following reasons, and I discussed it with the patient”? The jury will want to know whether the care that was provided was reasonable.

Costs and consequences of being sued

Question from the audience: What does it cost to mount a defense in a malpractice trial?

Mr. Donnelly: You can easily spend more than $100,000 to go through a trial. Plaintiffs typically have three or four experts in various cities across the country, and you have to pay your lawyers to travel to those cities and take the depositions. And delays often occur. Cases get filed, dismissed, and refiled. A lot of the work that the lawyers did to prepare for the trial will have to be redone for a second, third, or fourth time as new dates for the trial are set. There are many unforeseen costs.

Dr. Michota: Let’s say the physician who did the preoperative evaluation in this case was not affiliated with the hospital and wasn’t involved in the surgery or any of the postoperative monitoring and management, which we see may have been questionable. This physician might get pulled into the case anyway because he didn’t order an ECG in the preoperative evaluation. Although an ECG wasn’t recommended in this case by the ACC/AHA guidelines, this doctor is looking at spending considerable time, energy, and money to defend himself. What if his attorney recommends that he settle for a nominal amount—say, $25,000—because it’s cheaper and easier? Are there repercussions for him as a physician when he pays out a settlement under his name?

Mr. Donnelly: Absolutely. He will be reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank, and when he renews his license or applies for a license to practice in another state, he must disclose that he has been sued and paid a settlement. The new consumer-targeted public reporting Web sites will also publicize this information. It is like a black mark against this doctor even though he never admitted any liability.

CASE 3: A CLEAR CASE OF NEGLIGENCE―WHO IS RESPONSIBLE

A 67-year-old man undergoes a laminectomy in the hospital. He develops shortness of breath postoperatively and is seen by the hospitalist team. He is started on full-dose weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for possible pulmonary embolism or acute coronary syndrome. His symptoms resolve and his workup is negative. It is a holiday weekend. The consultants sign off but do not stop the full-dose LMWH. The patient is discharged to the rehabilitation unit by the surgeon and the surgeon’s assistant, who include all the medications at discharge, including the full-dose LMWH. The patient is admitted to a subacute nursing facility, where the physiatrist transfers to the chart all the medications on which the patient was discharged.

The patient does well until postoperative day 7, when he develops urinary retention and can’t move his legs. At this point, someone finally questions why he is on the LMWH, and it is stopped. The patient undergoes emergency surgery to evacuate a huge spinal hematoma, but his neurologic function never recovers.

Dr. Michota: I think most of us would agree that there was negligence here. I bet a plaintiff’s attorney would love to have this case.

Mr. Donnelly: Absolutely. The patient can no longer walk, so it’s already a high-value case. It would be even more so if we supposed that the patient were only 45 years old and a corporate executive. That would make it a really high-value case.

Dr. Michota: What do you mean? Does a patient’s age or economic means matter to a plaintiff’s attorney?

Mr. Donnelly: Of course. For a plaintiff’s attorney, it’s always nice to have a case like this where there’s negligence, but the high-dollar cases typically involve a likable plaintiff who is a high wage earner with a good family. A plaintiff’s lawyer will take a case that may not be so strong on evidence of negligence if it’s likely that a jury will like the plaintiff and his or her family. Kids always help to sway a jury—jurors will feel sorry for them and want to help them. This case even has two surgeries, so the family’s medical bills will be especially high. It’s a great case for a plaintiff’s attorney.

Who’s at fault?

Dr. Michota: Let’s look at a few more case details. Once the various doctors involved in this case realized what happened, they got nervous and engaged in finger-pointing. The surgeons felt that the hospitalists should have stopped the LMWH. The hospitalists claimed that since they had signed off, the surgeons should have stopped it. The physiatrist said, “Who am I to decide to stop medications? I assumed that the hospital physicians checked the medications before sending the patient to the rehab facility.”

Interestingly, a hospitalist went back and made a chart entry after the second surgery. He wrote, “Late chart entry. Discussion with surgeon regarding LMWH. I told him to stop it.” Does that make him free and clear?

Mr. Donnelly: Actually, the hospitalist just shot his credibility, and now the jury is really angry. The dollar value of the case has just gone up.

Dr. Michota: Okay, suppose the hospitalist wouldn’t do something that obvious. Instead, he goes back to the chart after the fact, finds the same color pen as the entry at the time, and writes, “Patient is okay. Please stop LMWH,” and signs his name. Is there any way anyone is going to be able to figure that out?

Mr. Donnelly: All the other doctors and nurses will testify that the note was not in the chart before. The plaintiff will hire a handwriting expert and look at the different impressions on the paper, the inks, and the style of writing. Now the hospitalist has really escalated the situation and is liable for punitive damages, which will come out of his own pocket, since malpractice insurance doesn’t cover punitive damages. His license may be threatened. The jury will really be angered, and the plaintiff’s lawyer will love stoking the situation.

- Budetti PP, Waters TM. Medical malpractice law in the United States. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; May 2005. Available at: www.kff.org/insurance/index.cfm. Accessed July 9, 2009.

- Harvard Medical Practice Study Group. Patients, doctors and lawyers: medical injury, malpractice litigation, and patient compensation in New York. Albany, NY: New York Department of Health; October 1990. Available at: http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/scandoclinks/OCM21331963.htm. Accessed June 29, 2009.

- Statistical Compilation of Annual Statement Information for Property/Casualty Insurance Companies in 2000. Kansas City, MO: National Association of Insurance Commissioners; 2001.

- Jury Verdict Research Web site. http://www.juryverdictresearch.com. Accessed June 29, 2009.

- National Practitioner Data Bank 2006 Annual Report. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: www.npdb-hipdb.hrsa.gov/annualrpt.html. Accessed July 9, 2009.

If this is a typical audience of physicians involved in perioperative care, about 35% to 40% of you have been sued for malpractice and have learned the hard way some of the lessons we will discuss today. This session will begin with an overview of malpractice law and medicolegal principles, after which we will review three real-life malpractice cases and open the floor to the audience for discussion of the lessons these cases can offer.

MALPRACTICE LAWSUITS ARE COMMON, EXPENSIVE, DAMAGING

If a physician practices long enough, lawsuits are nearly inevitable, especially in certain specialties. Surgeons and anesthesiologists are sued about once every 4 to 5 years; internists generally are sued less, averaging once every 7 to 10 years,1 but hospitalists and others who practice a good deal of perioperative care probably constitute a higher risk pool among internists.

At the same time, it is estimated that only one in eight preventable medical errors committed in hospitals results in a malpractice claim.2 From 1995 to 2000, the number of new malpractice claims actually declined by approximately 4%.3

Jury awards can be huge

Fewer than half (42%) of verdicts in malpractice cases are won by plaintiffs.4 But when plaintiffs succeed, the awards can be costly: the mean amount of physician malpractice payments in the United States in 2006 (the most recent data available) was $311,965, according to the National Practitioner Data Bank.5 Cases that involve a death result in substantially higher payments, averaging $1.4 million.4

Lawsuits are traumatic

Even if a physician is covered by good malpractice insurance, a malpractice lawsuit typically changes his or her life. It causes major disruption to the physician’s practice and may damage his or her reputation. Lawsuits cause considerable emotional distress, including a loss of self-esteem, particularly if the physician feels that a mistake was made in the delivery of care.

CATEGORIES OF CLAIMS IN MALPRACTICE LAW

Malpractice law involves torts, which are civil wrongs causing injury to a person or property for which the plaintiff may seek redress through the courts. In general, the plaintiff seeks financial compensation. Practitioners do not go to jail for committing malpractice unless a district attorney decides that the harm was committed intentionally, in which case criminal charges may be brought.

There are many different categories of claims in malpractice law. The most common pertaining to perioperative medicine involve issues surrounding informed consent and medical negligence (the worst form being wrongful death).

Informed consent

Although everyone is familiar with informed consent, details of the process are called into question when something goes wrong. Informed consent is based on the right of patient autonomy: each person has a right to determine what will be done to his or her body, which includes the right to consent to or refuse treatment.

For any procedure, treatment, or medication, patients should be informed about the following:

- The nature of the intervention

- The benefits of the intervention (why it is being recommended)

- Significant risks reasonably expected to exist

- Available alternatives (including “no treatment”).

If possible, it is important that the patient’s family understand the risks involved, because if the patient dies or becomes incapacitated, a family that is surprised by the outcome is more likely to sue.

The standard to which physicians are held in malpractice suits is that of a “reasonable physician” dealing with a “reasonable patient.” Often, a plaintiff claims that he or she did not know that a specific risk was involved, and the doctor claims that he or she spent a “typical” amount of time explaining all the risks. If that amount of time was only a few seconds, that may not pass the “reasonable physician” test, as a jury might conclude that more time may have been necessary.

Negligence and wrongful death

Negligence, including wrongful death, is a very common category of claim. The plaintiff generally must demonstrate four elements in negligence claims:

- The provider had a duty to the patient

- The duty was breached

- An injury occurred

- The breach of duty was a “proximate cause” of the injury.

Duty arises from the physician-patient relationship: any person whose name is on the medical chart essentially has a duty to the patient and can be brought into the case, even if the involvement was only peripheral.

Breach of duty. Determining whether a breach of duty occurred often involves a battle of medical experts. The standard of care is defined as what a reasonable practitioner would do under the same or similar circumstances, assuming similar training and background. The jury decides whether the physician met the standard of care based on testimony from experts.

The Latin phrase res ipsa loquitur means “the thing speaks for itself.” In surgery, the classic example is if an instrument or a towel were accidentally left in a patient. In such a situation, the breach of duty is obvious, so the strategy of the defense generally must be to show that the patient was not harmed by the breach.

Injury. The concept of injury can be broad and often depends on distinguishing bad practice from a bad or unfortunate outcome. For instance, a patient who suffered multisystem trauma but whose life was saved by medical intervention could sue if he ended up with paresthesia in the foot afterwards. An expert may be called to help determine whether or not the complication is reasonable for the particular medical situation. Patient expectations usually factor prominently into questions of injury.

Proximate cause often enters into situations involving wrongful death. A clear understanding of the cause of death or evidence from an autopsy is not necessarily required for a plaintiff to argue that malpractice was a proximate cause of death. A plaintiff’s attorney will often speculate why a patient died, and because the plaintiff’s burden of proof is so low (see next paragraph), it may not help the defense to argue that it is pure speculation that a particular event was related to the death.

A low burden of proof

In a civil tort, the burden of proof is established by a “preponderance of the evidence,” meaning that the allegation is “more likely than not.” This is a much lower standard than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” threshold used for criminal proceedings. In other words, the plaintiff has to show only that the chance that malpractice occurred was greater than 50%.

Three types of damages

Potential damages (financial compensation) in malpractice suits fall into three categories:

- Economic, or the monetary costs of an injury (eg, medical bills or loss of income)

- Noneconomic (eg, pain and suffering, loss of ability to have sex)

- Punitive, or damages to punish a defendant for willful and wanton conduct.

Punitive damages are generally not covered by malpractice insurance policies and are only rarely involved in cases against an individual physician. They are more often awarded when deep pockets are perceived to be involved, such as in a case against a hospital system or an insurance company, and when the jury wants to punish the entity for doing something that was believed to be willful.

REDUCING THE RISK OF BEING SUED

Regardless of the circumstances, communication is probably the most important factor determining whether a physician will be sued. Sometimes a doctor does everything right medically but gets sued because of lack of communication with the patient. Conversely, many of us know of veteran physicians who still practice medicine as they did 35 years ago but are never sued because they have a great rapport with their patients and their patients love them for it.

The importance of careful charting also cannot be overemphasized. In malpractice cases, experts for the plaintiff will comb through the medical records and be sure to notice if something is missing. The plaintiff also benefits enormously if, for instance, nurses documented that they paged the doctor many times over a 3-day period and got no response.

CASE 1: PATIENT DIES DURING PREOPERATIVE STRESS TEST FOR KNEE SURGERY

A 65-year-old man with New York Heart Association class III cardiac disease (marked limitation of physical activity) is scheduled for a total knee arthroplasty and is seen at the preoperative testing center. His past medical history includes coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and prior repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. He is referred for a preoperative stress test.

Dobutamine stress echocardiography is performed. His target heart rate is reached at 132 beats per minute with sporadic premature ventricular contractions. Toward the end of the test, he complains of shortness of breath and chest pain. The test is terminated, and the patient goes into ventricular tachycardia and then ventricular fibrillation. Despite resuscitative efforts, he dies.

Dr. Michota: From the family’s perspective, this patient had come for quality-of-life–enhancing surgery. They were looking forward to him getting a new knee so he could play golf again when he retired. The doctor convinced them that he needed a stress test first, which ends up killing him. Mr. Donnelly, as a lawyer, would you want to be the plaintiff’s attorney in this case?

Mr. Donnelly: Very much so. The family never contemplated that their loved one would die from this procedure. The first issue would be whether or not the possibility of complications or death from the stress test had been discussed with the patient or his family.

Consent must be truly ‘informed’ and documented

Dr. Michota: How many of our audience members who do preoperative assessments and refer patients for stress testing can recall a conversation with a patient that included the comment, “You may die from getting this test”? Before this case occurred, I never brought up this possibility, but I do now. This case illustrates how important expectations are.

Comment from the audience: I think you have to be careful of your own bias about risks. You might say to the patient, “There’s a risk that you’ll have an arrhythmia and die,” but if you also tell him, “I’ve never seen that happen during a stress test in my 10 years of practice,” you’ve biased the informed consent. The family can say, “Well, he basically told us that it wasn’t going to happen; he’d never seen a case of it.”

Dr. Michota: Are there certain things we shouldn’t say? Surely you should never promise somebody a good outcome by saying that certain rare events never happen.

Mr. Donnelly: That’s true. You can give percentages. You might say, “I’m letting you know there’s a possibility that you could die from this, but it’s a low percentage risk.” That way, you are informing the patient. This relates to the “reasonable physician” and “reasonable patient” standard. You are expected to do what is reasonable.

Is a signed consent form adequate defense?

Dr. Michota: What should the defense team do now? Let’s say informed consent was obtained and documented at the stress lab. The patient signed a form that listed death as a risk, but no family members were present. Is this an adequate defense?

Mr. Donnelly: It depends on whether the patient understood what was on the form and had the opportunity to ask questions.

Dr. Michota: So the form means nothing?

Mr. Donnelly: If he didn’t understand it, that is correct.

Dr. Michota: We thought he understood it. Can’t we just say, “Of course he understood it—he signed it.”

Mr. Donnelly: No. Keep in mind that most jurors have been patients at one time or another. There may be a perception that physicians are rushed or don’t have time to answer questions. Communication is really important here.

Dr. Michota: But surely there’s a physician on the jury who can help talk to the other jurors about how it really works.

Mr. Donnelly: No, a “jury of peers” is not a jury box of physicians. The plaintiff’s attorneys tend to exclude scientists and other educated professionals from the jury; they don’t want jurors who are accustomed to holding people to certain standards. They prefer young, impressionable people who wouldn’t think twice about awarding somebody $20 million.

Who should be obtaining informed consent?

Question from the audience: Who should have obtained informed consent for this patient—the doctor who referred him for the stress test or the cardiologist who conducted the test? Sometimes I have to get informed consent for specialty procedures that I myself do not understand very well. Could I be considered culpable even though I’m not the one doing the procedure? I can imagine an attorney asking, “Doctor, are you a cardiologist? How many of these tests do you do? Why are you the one doing the informed consent? Did the patient really understand the effects of the test? Do you really understand them?”

Dr. Michota: That question is even more pertinent if the patient is referred to another institution covered under different malpractice insurance. You can bet the other provider will try to blame you if something goes wrong.

Mr. Donnelly: In an ideal world, both the referring physician and the physician who does the test discuss the risks, benefits, and alternatives, and answer all questions that the patient and family have. The discussion is properly documented in the medical record.

Question from the audience: Can you address the issue of supervision? What is the liability of a resident or intern in doing the informed consent?

Mr. Donnelly: The attending physician is usually responsible for everything that a resident does. I would prefer that the attending obtain the informed consent.

Dr. Michota: But our fellows and second-year postgraduate residents are independent licensed practitioners in Ohio. Does letting them handle informed consent pose a danger to a defense team’s legal case?

Mr. Donnelly: It’s not necessarily a danger medically, but it gives the plaintiff something to talk about. They will ignore the fact that an independent licensed practitioner obtained the informed consent. They will simply focus on the fact that the physician was a resident or fellow. They will claim, “They had this young, inexperienced doctor give the informed consent when there were staff physicians with 20 years of experience who should have done it.” Plaintiffs will attempt to get a lot of mileage out of these minor issues.

Question from the audience: At our institution, the physician is present with the technician, so that when the physician obtains consent, the technician signs as a witness. The bottom of the long form basically says, “By signing this form, I attest that the physician performing the test has informed me of the benefits and risks of this test, and I agree to go ahead. I fully understand the implications of the test.” Does that have value in the eyes of the law?

Mr. Donnelly: That’s a great informed consent process and will have great value. That said, you can still get sued, because you can get sued for anything. But the jury ultimately decides, and odds are that with a process like yours they will conclude that the patient knew all the risks and benefits and alternatives because he or she signed the form and the doctor documented that everything was discussed.

Confidentiality vs family involvement

Comment from the audience: I’m struck by the comments that informed consent is supposed to be with the family so that there will be living witnesses in case the patient dies. According to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations, we have to be very careful to maintain confidentiality. For a competent patient, medical discussions are private unless specific permission has been obtained to involve the family.

Mr. Donnelly: Yes, we’ve assumed that the patient gave permission to discuss these issues with his family. If the patient does not want that, obviously you can’t include the family because of HIPAA regulations.

Question from the audience: Should we routinely ask a patient to involve the family in an informed consent in case something goes wrong?

Mr. Donnelly: No. In general, it’s appropriate only if the family is already present.

Dr. Michota: Keep in mind that there’s nothing you can do to completely prevent being sued. You can do everything right and still get sued. If you’re following good clinical practice and a patient doesn’t want to involve the family, all you can do is document your discussion and that you believed the patient understood the risks of the procedure.

Question from the audience: Do you consider a patient’s decision-making capacity for informed consent? Should physicians document it prior to obtaining consent? A plaintiff can always claim that an elderly patient did not understand.

Mr. Donnelly: I have never seen specific documentation that a patient had capacity to consent, but it’s a good idea for a borderline case. For such a case, it’s especially important to involve the family and document, “I discussed the matter with this elderly patient and her husband and three daughters.” You could also get a psychiatric consult or a social worker to help determine whether a patient has the capacity to make legal and medical decisions.

CASE 2: FATAL POSTSURGICAL MI RAISES QUESTIONS ABOUT THE PREOP EVALUATION

A 75-year-old man with rectal cancer presents for colorectal surgery. He has a remote cardiac history but exercises regularly and has a good functional classification without symptoms. The surgery is uneventful, but the patient develops hypotension in the postanesthesia care unit. He improves the next morning and goes to the colorectal surgery ward. Internal bleeding occurs but initially goes unrecognized; on postoperative day 2, his hemoglobin is found to be 2 g/dL and he is transferred to the intensive care unit, then back to the operating room, where he suffers cardiac arrest. He is revived but dies 2 weeks later. Autopsy reveals that he died of a myocardial infarction (MI).

Dr. Michota: The complaint in this case is that the patient did not receive a proper preoperative evaluation because no cardiac workup was done. As the hypothetical defense attorney, do you feel this case has merit? The patient most likely had an MI from demand ischemia due to hemorrhage, but does this have anything to do with not having a cardiac workup?

Mr. Donnelly: You as the physician are saying that even if he had an electrocardiogram (ECG), it is likely that nothing would have been determined. The cardiac problems he had prior to the surgery in question were well controlled, occurred in the distant past, and may not have affected the outcome. Maybe his remote cardiac problems were irrelevant and something else caused the MI that killed him. Nevertheless, the fact that the ECG wasn’t done still could be a major issue for the plaintiff’s attorney. After the fact, it seems like a no-brainer that an ECG should have been done in a case like this, and it’s easy for the plaintiff to argue that it might have detected something. The defense has to keep reminding the jury that the case cannot be looked at retrospectively, and that’s a tall order.

Dr. Michota: This case shows that even in the context of high-quality care, such things can happen. We have spent a lot of time at this summit talking about guidelines. But at the end of the day, if somebody dies perioperatively of an MI, the family may start looking for blame and any plaintiff’s attorney will go through the record to see if a preoperative ECG was done. If it wasn’t, a suit will get filed.

The four Cs offer the best protection

Question from the audience: Even if the physician had done the ECG, how do you know the plaintiff’s attorney wouldn’t attack him for not ordering a stress test? And if he had done a stress test, then they’d ask why he didn’t order a catheterization. Where is it going to end?

Dr. Michota: You make a good point. The best way for physicians to protect themselves is to follow the four Cs mentioned earlier: competent care, communication, compassion, and charting. After I learned about this case, the next time I was in the clinic and didn’t order an ECG, I asked the patient, “Did you expect that we would do an ECG here today?” When he responded that he did, I talked to him about how it wasn’t indicated and probably would not change management. So that level of communication can sometimes prevent a lawsuit that might stem from a patient not feeling informed. I’m not suggesting that you spend hours explaining details with each patient, but it’s good to be aware that cases like this happen and how you can reduce their likelihood.

Battles of the experts

Question from the audience: Exactly what standard is applied when the “standard of care” is determined in a court? For instance, my hospital may routinely order stress tests, whereas the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines are more restrictive in recommending when a stress test is indicated. Which standard would apply in court?

Dr. Michota: It’s easy to find a plaintiff’s expert who will say just about anything. If you claim that everybody gets a stress test at your community hospital and a patient dies during the stress test, the plaintiff’s team will find an expert to say, “That was an unnecessary test and posed an unnecessary risk.” If you’re in a setting where stress tests are rarely done for preoperative evaluation, they’ll find an expert to say, “Stress testing was available; it should have been done.”

This is when the battles of the experts occur. If you have a superstar physician on your defense team, the plaintiff will have to find someone of equal pedigree who can argue against him or her. Sometimes cases go away because the defense lines up amazing experts and the plaintiffs lose their stomach for the money it would take to bring the case forward. But usually cases do not involve that caliber of experts; most notables in the field are academic physicians who don’t do this type of work. Usually you get busy physicians who spend 75% of their time in clinical practice and seem smart enough to impress the jury. Although they can say things that aren’t even factual, they can sway the jury.

Question from the audience: I would not have ordered a preoperative ECG on this healthy 75-year-old, but one of the experts at this summit said that he would get a baseline ECG for such a case. How are differences like these reconciled in the legal context?

Dr. Michota: The standard to which we are held is that of a reasonable physician. Can you show that your approach was a reasonable one? Can you say, “I didn’t order the ECG for the following reasons, and I discussed the issue with the patient”? Or alternately, “An ECG was ordered for the following reasons, and I discussed it with the patient”? The jury will want to know whether the care that was provided was reasonable.

Costs and consequences of being sued

Question from the audience: What does it cost to mount a defense in a malpractice trial?

Mr. Donnelly: You can easily spend more than $100,000 to go through a trial. Plaintiffs typically have three or four experts in various cities across the country, and you have to pay your lawyers to travel to those cities and take the depositions. And delays often occur. Cases get filed, dismissed, and refiled. A lot of the work that the lawyers did to prepare for the trial will have to be redone for a second, third, or fourth time as new dates for the trial are set. There are many unforeseen costs.

Dr. Michota: Let’s say the physician who did the preoperative evaluation in this case was not affiliated with the hospital and wasn’t involved in the surgery or any of the postoperative monitoring and management, which we see may have been questionable. This physician might get pulled into the case anyway because he didn’t order an ECG in the preoperative evaluation. Although an ECG wasn’t recommended in this case by the ACC/AHA guidelines, this doctor is looking at spending considerable time, energy, and money to defend himself. What if his attorney recommends that he settle for a nominal amount—say, $25,000—because it’s cheaper and easier? Are there repercussions for him as a physician when he pays out a settlement under his name?

Mr. Donnelly: Absolutely. He will be reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank, and when he renews his license or applies for a license to practice in another state, he must disclose that he has been sued and paid a settlement. The new consumer-targeted public reporting Web sites will also publicize this information. It is like a black mark against this doctor even though he never admitted any liability.

CASE 3: A CLEAR CASE OF NEGLIGENCE―WHO IS RESPONSIBLE

A 67-year-old man undergoes a laminectomy in the hospital. He develops shortness of breath postoperatively and is seen by the hospitalist team. He is started on full-dose weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for possible pulmonary embolism or acute coronary syndrome. His symptoms resolve and his workup is negative. It is a holiday weekend. The consultants sign off but do not stop the full-dose LMWH. The patient is discharged to the rehabilitation unit by the surgeon and the surgeon’s assistant, who include all the medications at discharge, including the full-dose LMWH. The patient is admitted to a subacute nursing facility, where the physiatrist transfers to the chart all the medications on which the patient was discharged.

The patient does well until postoperative day 7, when he develops urinary retention and can’t move his legs. At this point, someone finally questions why he is on the LMWH, and it is stopped. The patient undergoes emergency surgery to evacuate a huge spinal hematoma, but his neurologic function never recovers.

Dr. Michota: I think most of us would agree that there was negligence here. I bet a plaintiff’s attorney would love to have this case.

Mr. Donnelly: Absolutely. The patient can no longer walk, so it’s already a high-value case. It would be even more so if we supposed that the patient were only 45 years old and a corporate executive. That would make it a really high-value case.

Dr. Michota: What do you mean? Does a patient’s age or economic means matter to a plaintiff’s attorney?

Mr. Donnelly: Of course. For a plaintiff’s attorney, it’s always nice to have a case like this where there’s negligence, but the high-dollar cases typically involve a likable plaintiff who is a high wage earner with a good family. A plaintiff’s lawyer will take a case that may not be so strong on evidence of negligence if it’s likely that a jury will like the plaintiff and his or her family. Kids always help to sway a jury—jurors will feel sorry for them and want to help them. This case even has two surgeries, so the family’s medical bills will be especially high. It’s a great case for a plaintiff’s attorney.

Who’s at fault?

Dr. Michota: Let’s look at a few more case details. Once the various doctors involved in this case realized what happened, they got nervous and engaged in finger-pointing. The surgeons felt that the hospitalists should have stopped the LMWH. The hospitalists claimed that since they had signed off, the surgeons should have stopped it. The physiatrist said, “Who am I to decide to stop medications? I assumed that the hospital physicians checked the medications before sending the patient to the rehab facility.”

Interestingly, a hospitalist went back and made a chart entry after the second surgery. He wrote, “Late chart entry. Discussion with surgeon regarding LMWH. I told him to stop it.” Does that make him free and clear?

Mr. Donnelly: Actually, the hospitalist just shot his credibility, and now the jury is really angry. The dollar value of the case has just gone up.

Dr. Michota: Okay, suppose the hospitalist wouldn’t do something that obvious. Instead, he goes back to the chart after the fact, finds the same color pen as the entry at the time, and writes, “Patient is okay. Please stop LMWH,” and signs his name. Is there any way anyone is going to be able to figure that out?

Mr. Donnelly: All the other doctors and nurses will testify that the note was not in the chart before. The plaintiff will hire a handwriting expert and look at the different impressions on the paper, the inks, and the style of writing. Now the hospitalist has really escalated the situation and is liable for punitive damages, which will come out of his own pocket, since malpractice insurance doesn’t cover punitive damages. His license may be threatened. The jury will really be angered, and the plaintiff’s lawyer will love stoking the situation.

If this is a typical audience of physicians involved in perioperative care, about 35% to 40% of you have been sued for malpractice and have learned the hard way some of the lessons we will discuss today. This session will begin with an overview of malpractice law and medicolegal principles, after which we will review three real-life malpractice cases and open the floor to the audience for discussion of the lessons these cases can offer.

MALPRACTICE LAWSUITS ARE COMMON, EXPENSIVE, DAMAGING

If a physician practices long enough, lawsuits are nearly inevitable, especially in certain specialties. Surgeons and anesthesiologists are sued about once every 4 to 5 years; internists generally are sued less, averaging once every 7 to 10 years,1 but hospitalists and others who practice a good deal of perioperative care probably constitute a higher risk pool among internists.

At the same time, it is estimated that only one in eight preventable medical errors committed in hospitals results in a malpractice claim.2 From 1995 to 2000, the number of new malpractice claims actually declined by approximately 4%.3

Jury awards can be huge

Fewer than half (42%) of verdicts in malpractice cases are won by plaintiffs.4 But when plaintiffs succeed, the awards can be costly: the mean amount of physician malpractice payments in the United States in 2006 (the most recent data available) was $311,965, according to the National Practitioner Data Bank.5 Cases that involve a death result in substantially higher payments, averaging $1.4 million.4

Lawsuits are traumatic

Even if a physician is covered by good malpractice insurance, a malpractice lawsuit typically changes his or her life. It causes major disruption to the physician’s practice and may damage his or her reputation. Lawsuits cause considerable emotional distress, including a loss of self-esteem, particularly if the physician feels that a mistake was made in the delivery of care.

CATEGORIES OF CLAIMS IN MALPRACTICE LAW

Malpractice law involves torts, which are civil wrongs causing injury to a person or property for which the plaintiff may seek redress through the courts. In general, the plaintiff seeks financial compensation. Practitioners do not go to jail for committing malpractice unless a district attorney decides that the harm was committed intentionally, in which case criminal charges may be brought.

There are many different categories of claims in malpractice law. The most common pertaining to perioperative medicine involve issues surrounding informed consent and medical negligence (the worst form being wrongful death).

Informed consent

Although everyone is familiar with informed consent, details of the process are called into question when something goes wrong. Informed consent is based on the right of patient autonomy: each person has a right to determine what will be done to his or her body, which includes the right to consent to or refuse treatment.

For any procedure, treatment, or medication, patients should be informed about the following:

- The nature of the intervention

- The benefits of the intervention (why it is being recommended)

- Significant risks reasonably expected to exist

- Available alternatives (including “no treatment”).

If possible, it is important that the patient’s family understand the risks involved, because if the patient dies or becomes incapacitated, a family that is surprised by the outcome is more likely to sue.

The standard to which physicians are held in malpractice suits is that of a “reasonable physician” dealing with a “reasonable patient.” Often, a plaintiff claims that he or she did not know that a specific risk was involved, and the doctor claims that he or she spent a “typical” amount of time explaining all the risks. If that amount of time was only a few seconds, that may not pass the “reasonable physician” test, as a jury might conclude that more time may have been necessary.

Negligence and wrongful death

Negligence, including wrongful death, is a very common category of claim. The plaintiff generally must demonstrate four elements in negligence claims:

- The provider had a duty to the patient

- The duty was breached

- An injury occurred

- The breach of duty was a “proximate cause” of the injury.

Duty arises from the physician-patient relationship: any person whose name is on the medical chart essentially has a duty to the patient and can be brought into the case, even if the involvement was only peripheral.

Breach of duty. Determining whether a breach of duty occurred often involves a battle of medical experts. The standard of care is defined as what a reasonable practitioner would do under the same or similar circumstances, assuming similar training and background. The jury decides whether the physician met the standard of care based on testimony from experts.

The Latin phrase res ipsa loquitur means “the thing speaks for itself.” In surgery, the classic example is if an instrument or a towel were accidentally left in a patient. In such a situation, the breach of duty is obvious, so the strategy of the defense generally must be to show that the patient was not harmed by the breach.

Injury. The concept of injury can be broad and often depends on distinguishing bad practice from a bad or unfortunate outcome. For instance, a patient who suffered multisystem trauma but whose life was saved by medical intervention could sue if he ended up with paresthesia in the foot afterwards. An expert may be called to help determine whether or not the complication is reasonable for the particular medical situation. Patient expectations usually factor prominently into questions of injury.

Proximate cause often enters into situations involving wrongful death. A clear understanding of the cause of death or evidence from an autopsy is not necessarily required for a plaintiff to argue that malpractice was a proximate cause of death. A plaintiff’s attorney will often speculate why a patient died, and because the plaintiff’s burden of proof is so low (see next paragraph), it may not help the defense to argue that it is pure speculation that a particular event was related to the death.

A low burden of proof

In a civil tort, the burden of proof is established by a “preponderance of the evidence,” meaning that the allegation is “more likely than not.” This is a much lower standard than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” threshold used for criminal proceedings. In other words, the plaintiff has to show only that the chance that malpractice occurred was greater than 50%.

Three types of damages

Potential damages (financial compensation) in malpractice suits fall into three categories:

- Economic, or the monetary costs of an injury (eg, medical bills or loss of income)

- Noneconomic (eg, pain and suffering, loss of ability to have sex)

- Punitive, or damages to punish a defendant for willful and wanton conduct.

Punitive damages are generally not covered by malpractice insurance policies and are only rarely involved in cases against an individual physician. They are more often awarded when deep pockets are perceived to be involved, such as in a case against a hospital system or an insurance company, and when the jury wants to punish the entity for doing something that was believed to be willful.

REDUCING THE RISK OF BEING SUED

Regardless of the circumstances, communication is probably the most important factor determining whether a physician will be sued. Sometimes a doctor does everything right medically but gets sued because of lack of communication with the patient. Conversely, many of us know of veteran physicians who still practice medicine as they did 35 years ago but are never sued because they have a great rapport with their patients and their patients love them for it.

The importance of careful charting also cannot be overemphasized. In malpractice cases, experts for the plaintiff will comb through the medical records and be sure to notice if something is missing. The plaintiff also benefits enormously if, for instance, nurses documented that they paged the doctor many times over a 3-day period and got no response.

CASE 1: PATIENT DIES DURING PREOPERATIVE STRESS TEST FOR KNEE SURGERY

A 65-year-old man with New York Heart Association class III cardiac disease (marked limitation of physical activity) is scheduled for a total knee arthroplasty and is seen at the preoperative testing center. His past medical history includes coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and prior repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. He is referred for a preoperative stress test.

Dobutamine stress echocardiography is performed. His target heart rate is reached at 132 beats per minute with sporadic premature ventricular contractions. Toward the end of the test, he complains of shortness of breath and chest pain. The test is terminated, and the patient goes into ventricular tachycardia and then ventricular fibrillation. Despite resuscitative efforts, he dies.

Dr. Michota: From the family’s perspective, this patient had come for quality-of-life–enhancing surgery. They were looking forward to him getting a new knee so he could play golf again when he retired. The doctor convinced them that he needed a stress test first, which ends up killing him. Mr. Donnelly, as a lawyer, would you want to be the plaintiff’s attorney in this case?

Mr. Donnelly: Very much so. The family never contemplated that their loved one would die from this procedure. The first issue would be whether or not the possibility of complications or death from the stress test had been discussed with the patient or his family.

Consent must be truly ‘informed’ and documented

Dr. Michota: How many of our audience members who do preoperative assessments and refer patients for stress testing can recall a conversation with a patient that included the comment, “You may die from getting this test”? Before this case occurred, I never brought up this possibility, but I do now. This case illustrates how important expectations are.

Comment from the audience: I think you have to be careful of your own bias about risks. You might say to the patient, “There’s a risk that you’ll have an arrhythmia and die,” but if you also tell him, “I’ve never seen that happen during a stress test in my 10 years of practice,” you’ve biased the informed consent. The family can say, “Well, he basically told us that it wasn’t going to happen; he’d never seen a case of it.”

Dr. Michota: Are there certain things we shouldn’t say? Surely you should never promise somebody a good outcome by saying that certain rare events never happen.

Mr. Donnelly: That’s true. You can give percentages. You might say, “I’m letting you know there’s a possibility that you could die from this, but it’s a low percentage risk.” That way, you are informing the patient. This relates to the “reasonable physician” and “reasonable patient” standard. You are expected to do what is reasonable.

Is a signed consent form adequate defense?

Dr. Michota: What should the defense team do now? Let’s say informed consent was obtained and documented at the stress lab. The patient signed a form that listed death as a risk, but no family members were present. Is this an adequate defense?

Mr. Donnelly: It depends on whether the patient understood what was on the form and had the opportunity to ask questions.

Dr. Michota: So the form means nothing?

Mr. Donnelly: If he didn’t understand it, that is correct.

Dr. Michota: We thought he understood it. Can’t we just say, “Of course he understood it—he signed it.”

Mr. Donnelly: No. Keep in mind that most jurors have been patients at one time or another. There may be a perception that physicians are rushed or don’t have time to answer questions. Communication is really important here.

Dr. Michota: But surely there’s a physician on the jury who can help talk to the other jurors about how it really works.

Mr. Donnelly: No, a “jury of peers” is not a jury box of physicians. The plaintiff’s attorneys tend to exclude scientists and other educated professionals from the jury; they don’t want jurors who are accustomed to holding people to certain standards. They prefer young, impressionable people who wouldn’t think twice about awarding somebody $20 million.

Who should be obtaining informed consent?

Question from the audience: Who should have obtained informed consent for this patient—the doctor who referred him for the stress test or the cardiologist who conducted the test? Sometimes I have to get informed consent for specialty procedures that I myself do not understand very well. Could I be considered culpable even though I’m not the one doing the procedure? I can imagine an attorney asking, “Doctor, are you a cardiologist? How many of these tests do you do? Why are you the one doing the informed consent? Did the patient really understand the effects of the test? Do you really understand them?”

Dr. Michota: That question is even more pertinent if the patient is referred to another institution covered under different malpractice insurance. You can bet the other provider will try to blame you if something goes wrong.

Mr. Donnelly: In an ideal world, both the referring physician and the physician who does the test discuss the risks, benefits, and alternatives, and answer all questions that the patient and family have. The discussion is properly documented in the medical record.

Question from the audience: Can you address the issue of supervision? What is the liability of a resident or intern in doing the informed consent?

Mr. Donnelly: The attending physician is usually responsible for everything that a resident does. I would prefer that the attending obtain the informed consent.

Dr. Michota: But our fellows and second-year postgraduate residents are independent licensed practitioners in Ohio. Does letting them handle informed consent pose a danger to a defense team’s legal case?

Mr. Donnelly: It’s not necessarily a danger medically, but it gives the plaintiff something to talk about. They will ignore the fact that an independent licensed practitioner obtained the informed consent. They will simply focus on the fact that the physician was a resident or fellow. They will claim, “They had this young, inexperienced doctor give the informed consent when there were staff physicians with 20 years of experience who should have done it.” Plaintiffs will attempt to get a lot of mileage out of these minor issues.

Question from the audience: At our institution, the physician is present with the technician, so that when the physician obtains consent, the technician signs as a witness. The bottom of the long form basically says, “By signing this form, I attest that the physician performing the test has informed me of the benefits and risks of this test, and I agree to go ahead. I fully understand the implications of the test.” Does that have value in the eyes of the law?

Mr. Donnelly: That’s a great informed consent process and will have great value. That said, you can still get sued, because you can get sued for anything. But the jury ultimately decides, and odds are that with a process like yours they will conclude that the patient knew all the risks and benefits and alternatives because he or she signed the form and the doctor documented that everything was discussed.

Confidentiality vs family involvement

Comment from the audience: I’m struck by the comments that informed consent is supposed to be with the family so that there will be living witnesses in case the patient dies. According to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations, we have to be very careful to maintain confidentiality. For a competent patient, medical discussions are private unless specific permission has been obtained to involve the family.

Mr. Donnelly: Yes, we’ve assumed that the patient gave permission to discuss these issues with his family. If the patient does not want that, obviously you can’t include the family because of HIPAA regulations.

Question from the audience: Should we routinely ask a patient to involve the family in an informed consent in case something goes wrong?

Mr. Donnelly: No. In general, it’s appropriate only if the family is already present.

Dr. Michota: Keep in mind that there’s nothing you can do to completely prevent being sued. You can do everything right and still get sued. If you’re following good clinical practice and a patient doesn’t want to involve the family, all you can do is document your discussion and that you believed the patient understood the risks of the procedure.

Question from the audience: Do you consider a patient’s decision-making capacity for informed consent? Should physicians document it prior to obtaining consent? A plaintiff can always claim that an elderly patient did not understand.

Mr. Donnelly: I have never seen specific documentation that a patient had capacity to consent, but it’s a good idea for a borderline case. For such a case, it’s especially important to involve the family and document, “I discussed the matter with this elderly patient and her husband and three daughters.” You could also get a psychiatric consult or a social worker to help determine whether a patient has the capacity to make legal and medical decisions.

CASE 2: FATAL POSTSURGICAL MI RAISES QUESTIONS ABOUT THE PREOP EVALUATION

A 75-year-old man with rectal cancer presents for colorectal surgery. He has a remote cardiac history but exercises regularly and has a good functional classification without symptoms. The surgery is uneventful, but the patient develops hypotension in the postanesthesia care unit. He improves the next morning and goes to the colorectal surgery ward. Internal bleeding occurs but initially goes unrecognized; on postoperative day 2, his hemoglobin is found to be 2 g/dL and he is transferred to the intensive care unit, then back to the operating room, where he suffers cardiac arrest. He is revived but dies 2 weeks later. Autopsy reveals that he died of a myocardial infarction (MI).

Dr. Michota: The complaint in this case is that the patient did not receive a proper preoperative evaluation because no cardiac workup was done. As the hypothetical defense attorney, do you feel this case has merit? The patient most likely had an MI from demand ischemia due to hemorrhage, but does this have anything to do with not having a cardiac workup?

Mr. Donnelly: You as the physician are saying that even if he had an electrocardiogram (ECG), it is likely that nothing would have been determined. The cardiac problems he had prior to the surgery in question were well controlled, occurred in the distant past, and may not have affected the outcome. Maybe his remote cardiac problems were irrelevant and something else caused the MI that killed him. Nevertheless, the fact that the ECG wasn’t done still could be a major issue for the plaintiff’s attorney. After the fact, it seems like a no-brainer that an ECG should have been done in a case like this, and it’s easy for the plaintiff to argue that it might have detected something. The defense has to keep reminding the jury that the case cannot be looked at retrospectively, and that’s a tall order.

Dr. Michota: This case shows that even in the context of high-quality care, such things can happen. We have spent a lot of time at this summit talking about guidelines. But at the end of the day, if somebody dies perioperatively of an MI, the family may start looking for blame and any plaintiff’s attorney will go through the record to see if a preoperative ECG was done. If it wasn’t, a suit will get filed.

The four Cs offer the best protection