User login

NAPLES, FLA. – Without a single life lost at area hospitals, the medical response to the Boston Marathon bombings was by all accounts remarkable. But what if police and other first-responders had tourniquets and were trained in their use?

As it was, advanced topical hemostatic agents and tourniquets were MIA in the field, forcing all but one prehospital tourniquet to be improvised, according to Massachusetts General Hospital trauma surgeon Lt. Col. David King, U. S. Army Reserve.

"It’s abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work," he said. "The fact that every soldier down range has one in his pocket and we couldn’t muster up more than one in the city of Boston is a shame and we need to rectify that."

In all, there were 66 limb injuries, with 29 patients having recognized limb exsanguination at the scene. Of the 27 tourniquets applied, 26 were improvised.

Failure to translate this important lesson from military experience meant that these homemade devices were most likely wildly ineffective and, in some cases, may have even exacerbated blood loss, he said. Surprisingly, there’s no formal protocol for tourniquet application or training paradigm in Massachusetts, such that exists in the Army’s prehospital Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook.

"If you look across the paramedic medical guidelines, there is no protocol on the right, evidence-based way to put on a tourniquet or what the indications are for a tourniquet," Dr. King said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). "We don’t have it, and we need to" have it nationwide.

EAST is hoping to provide some guidance in this area with the development of practice management guidelines (PMG) for tourniquet use in extremity trauma. Dr. King, who heads this PMG committee, reported at the meeting that the guidelines, due out later this year, will emphasize that commercially made tourniquets should be available in the prehospital setting, improvised tourniquets rarely work and cannot be recommended; essentially all commercially made tourniquets are equieffective; and that nonmedical personnel can be trained to correctly apply a proper tourniquet.

The need for bleeding control equipment and training for the public has not gone unnoticed by other stakeholders and is the central focus of the newest statement from the Hartford Consensus, a collaborative group of trauma surgeons, law enforcement officers, and emergency responders led by the American College of Surgeons (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:467-75).

In dissecting the medical response to the Boston bombings, much has been made of the fact that Boston is home to six Level 1 trauma centers, and that it was race day, a city holiday, 3 p.m., and low-yield devices were used. Dr. King, however, gave high praise to an unsung hero, the Boston EMS loading officer who managed most of the transport destination decisions and smartly distributed critical cases throughout the area’s hospitals.

All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some have argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a "stay-and-play" mentality in the medical tent. The after-action review suggests there probably were enough ambulances to do the job in 30 minutes, said Dr. King, who remarked that the only thing that matters in critical trauma cases is time to surgical hemorrhage control.

"This will remain a controversial issue for Boston, whether staying and playing in the medical tent was a good idea," he said. "I don’t know what the right answer is."

Credit was also given to Massachusetts General, and many of the other city hospitals, for their insistence on regular full-scale drills that allowed quick lock-down of the facility to control access and manage the surge capacity in the emergency department.

"It’s more than just a tabletop exercise," Dr. King said. "When we test the surge capacity, we actually empty the emergency room for real. Usually, it occurs between 5:00 and 7:00 or 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning, but actually doing these things was useful, because when it came time to do it for real, no one was tripping over their own feet."

ED volume on that April afternoon was reduced from 97 patients to just 39 within 1.5 hours. Nontrauma physicians, including psychiatrists, did their part by writing "barebones orders" to get patients transferred to the wards.

Staff at Massachusetts General treated 43 patients, performing nine emergent operations, six amputations, two laparotomies, and one thoracotomy, with two traumatic arrests within the first 72 hours. As with other Boston hospitals, there were no in-hospital deaths, he said.

Patients arrived in such rapid succession, however, that it slowed the electronic medical record system and forced staff to use sequential record numbers, which can be dangerous. Registration couldn’t keep up and orders couldn’t be put in fast enough with 43 patients arriving in roughly 35 minutes, Dr. King explained. Workarounds were often old-school, and reminiscent of his days as a green trauma surgeon serving at Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

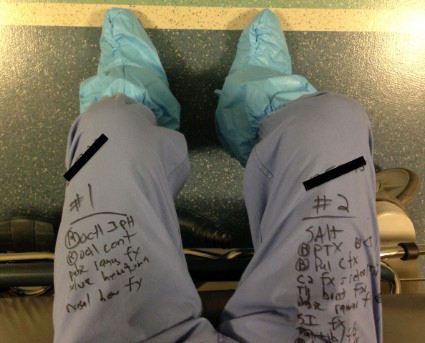

"In the midst of this entire event, I turned to my nurse practitioner and asked for x, y, z information on a particular patient," he said. "She didn’t turn to her tablet or desktop computer in the operating room. She pulled out a piece of paper where she’d written all the relevant information. At the end of the event, I looked down and realized I’d done the same thing. I was keeping track of my patients on my pants with a Sharpie."

King describes this as a failure of technology and translation from the battlefield, but noted that the hospital did use the military’s practice of reviewing a critical event. Once they’d finished in the operating room and achieved hemorrhage and contamination control, the entire trauma team was reassembled. They did detailed tertiary trauma surveys and went back through every single patient to determine what additional studies they needed, what injuries had been missed.

"It was remarkable the number of things that were missed," Dr. King said. "No one was bleeding to death, but tons and tons of [small, non–life threatening] missed injuries [like ruptured ear drums], and to me this was one of the more important events that surrounded our response to the entire bombing – sitting down after the dust had settled and carefully going over every patient’s medical record."

Dr. King reported having no financial disclosures.

Lt. Col. King makes some excellent points. However, despite Dr. King's combat medicine experience, his contribution to this article reveals a gap that still exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

The case against improvised tourniquets

There is no consensus on the definition of an "improvised" tourniquet. Homemade applications such as neckties and sticks are defined as improvised, but the Boston EMS kits (surgical tubing and Kelly clamps) also could be considered improvised. All of these methods may sound primitive since the advent of Combat-Application Tourniquets; however CATS are relatively new to the scene. Should we consider every tourniquet applied prior to their introduction to have been improvised? For the price of one CAT, we can assemble 10 tourniquet kits. And if Dr. King's initial contention was that tourniquets were in short supply, then it is a better system to deploy as many as possible. This point may be moot, however, because since the Boston bombing incident, federal grant money has allowed the purchase of CAT units in great numbers within the Metro-Boston area.

Tourniquet efficacy

"It is abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work." I feel this study had the wrong focus. Rather than ask which tourniquets have a better success rate, the study should have asked whose tourniquets have a better success rate.

Study after study has shown that successful intubation rates have little to do with the level of training of the practitioner, and everything to do with the frequency of intubation. More tubes equal more successful passes. I propose that this applies to tourniquet application as well. Field personnel who do not practice or have the opportunity to apply tourniquets frequently (which is the great majority of us) may not be applying tourniquets properly. This is why we instituted a massive tourniquet training and review program almost immediately following the 2013 bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Another point not addressed in studies is the effectiveness of nonresponder tourniquets. I would contend that an experienced practitioner with a necktie and a stick would be more successful in hemorrhage control that a civilian with a CAT, but those data have not been explored yet either.

The Loading Officer as unsung hero

All our Action Area Officers performed brilliantly (full disclosure, I was the Loading Officer). However the term Loading Officer is a misnomer. Yes, there is a Loading Officer, but there is actually a Loading Team. It consists of staff at the scene who liaise with the treatment areas and the true unsung heroes, the staff in the Operations Division or Dispatch Center. Dispatchers are in constant contact with the hospitals, scene operations, as well as continuing city service. They perform the hospital destination designations because they have a global sense of traffic, while at the scene we have only a worm's-eye view.

The stay-and-play critique

"All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a 'stay-and-play' mentality." I take exception to this assertion. First, the point is contradictory. All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but there was a stay-and-play mentality? Every EMT and paramedic knows that transport times translate into positive results with trauma.

Emergency personnel are taught that what matters most in trauma survival is not basic life support, advance life support, or wheelbarrow, but getting them to the ED fast. Yes, there were slowdowns in the medical tents, but most of delays came from non-EMS personnel who were not well versed in field medicine. We questioned, pleaded, and ultimately ordered some practitioners away from patients as they were attempting to perform procedures that we would never attempt on a trauma patient in the field. This is by no means a condemnation on my part. The staff we worked with was exceptional, and I witnessed true skill, heroism, and compassion. But it also demonstrated to me that a disconnect exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

I see an opportunity here for training to better acclimate responders to working together with our hospital counterparts. We also need hospital personnel to be oriented to realities and limitations of field medicine.

Lt. Brian Pomodoro is a member of the Boston EMS.

Lt. Col. King makes some excellent points. However, despite Dr. King's combat medicine experience, his contribution to this article reveals a gap that still exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

The case against improvised tourniquets

There is no consensus on the definition of an "improvised" tourniquet. Homemade applications such as neckties and sticks are defined as improvised, but the Boston EMS kits (surgical tubing and Kelly clamps) also could be considered improvised. All of these methods may sound primitive since the advent of Combat-Application Tourniquets; however CATS are relatively new to the scene. Should we consider every tourniquet applied prior to their introduction to have been improvised? For the price of one CAT, we can assemble 10 tourniquet kits. And if Dr. King's initial contention was that tourniquets were in short supply, then it is a better system to deploy as many as possible. This point may be moot, however, because since the Boston bombing incident, federal grant money has allowed the purchase of CAT units in great numbers within the Metro-Boston area.

Tourniquet efficacy

"It is abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work." I feel this study had the wrong focus. Rather than ask which tourniquets have a better success rate, the study should have asked whose tourniquets have a better success rate.

Study after study has shown that successful intubation rates have little to do with the level of training of the practitioner, and everything to do with the frequency of intubation. More tubes equal more successful passes. I propose that this applies to tourniquet application as well. Field personnel who do not practice or have the opportunity to apply tourniquets frequently (which is the great majority of us) may not be applying tourniquets properly. This is why we instituted a massive tourniquet training and review program almost immediately following the 2013 bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Another point not addressed in studies is the effectiveness of nonresponder tourniquets. I would contend that an experienced practitioner with a necktie and a stick would be more successful in hemorrhage control that a civilian with a CAT, but those data have not been explored yet either.

The Loading Officer as unsung hero

All our Action Area Officers performed brilliantly (full disclosure, I was the Loading Officer). However the term Loading Officer is a misnomer. Yes, there is a Loading Officer, but there is actually a Loading Team. It consists of staff at the scene who liaise with the treatment areas and the true unsung heroes, the staff in the Operations Division or Dispatch Center. Dispatchers are in constant contact with the hospitals, scene operations, as well as continuing city service. They perform the hospital destination designations because they have a global sense of traffic, while at the scene we have only a worm's-eye view.

The stay-and-play critique

"All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a 'stay-and-play' mentality." I take exception to this assertion. First, the point is contradictory. All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but there was a stay-and-play mentality? Every EMT and paramedic knows that transport times translate into positive results with trauma.

Emergency personnel are taught that what matters most in trauma survival is not basic life support, advance life support, or wheelbarrow, but getting them to the ED fast. Yes, there were slowdowns in the medical tents, but most of delays came from non-EMS personnel who were not well versed in field medicine. We questioned, pleaded, and ultimately ordered some practitioners away from patients as they were attempting to perform procedures that we would never attempt on a trauma patient in the field. This is by no means a condemnation on my part. The staff we worked with was exceptional, and I witnessed true skill, heroism, and compassion. But it also demonstrated to me that a disconnect exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

I see an opportunity here for training to better acclimate responders to working together with our hospital counterparts. We also need hospital personnel to be oriented to realities and limitations of field medicine.

Lt. Brian Pomodoro is a member of the Boston EMS.

Lt. Col. King makes some excellent points. However, despite Dr. King's combat medicine experience, his contribution to this article reveals a gap that still exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

The case against improvised tourniquets

There is no consensus on the definition of an "improvised" tourniquet. Homemade applications such as neckties and sticks are defined as improvised, but the Boston EMS kits (surgical tubing and Kelly clamps) also could be considered improvised. All of these methods may sound primitive since the advent of Combat-Application Tourniquets; however CATS are relatively new to the scene. Should we consider every tourniquet applied prior to their introduction to have been improvised? For the price of one CAT, we can assemble 10 tourniquet kits. And if Dr. King's initial contention was that tourniquets were in short supply, then it is a better system to deploy as many as possible. This point may be moot, however, because since the Boston bombing incident, federal grant money has allowed the purchase of CAT units in great numbers within the Metro-Boston area.

Tourniquet efficacy

"It is abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work." I feel this study had the wrong focus. Rather than ask which tourniquets have a better success rate, the study should have asked whose tourniquets have a better success rate.

Study after study has shown that successful intubation rates have little to do with the level of training of the practitioner, and everything to do with the frequency of intubation. More tubes equal more successful passes. I propose that this applies to tourniquet application as well. Field personnel who do not practice or have the opportunity to apply tourniquets frequently (which is the great majority of us) may not be applying tourniquets properly. This is why we instituted a massive tourniquet training and review program almost immediately following the 2013 bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Another point not addressed in studies is the effectiveness of nonresponder tourniquets. I would contend that an experienced practitioner with a necktie and a stick would be more successful in hemorrhage control that a civilian with a CAT, but those data have not been explored yet either.

The Loading Officer as unsung hero

All our Action Area Officers performed brilliantly (full disclosure, I was the Loading Officer). However the term Loading Officer is a misnomer. Yes, there is a Loading Officer, but there is actually a Loading Team. It consists of staff at the scene who liaise with the treatment areas and the true unsung heroes, the staff in the Operations Division or Dispatch Center. Dispatchers are in constant contact with the hospitals, scene operations, as well as continuing city service. They perform the hospital destination designations because they have a global sense of traffic, while at the scene we have only a worm's-eye view.

The stay-and-play critique

"All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a 'stay-and-play' mentality." I take exception to this assertion. First, the point is contradictory. All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but there was a stay-and-play mentality? Every EMT and paramedic knows that transport times translate into positive results with trauma.

Emergency personnel are taught that what matters most in trauma survival is not basic life support, advance life support, or wheelbarrow, but getting them to the ED fast. Yes, there were slowdowns in the medical tents, but most of delays came from non-EMS personnel who were not well versed in field medicine. We questioned, pleaded, and ultimately ordered some practitioners away from patients as they were attempting to perform procedures that we would never attempt on a trauma patient in the field. This is by no means a condemnation on my part. The staff we worked with was exceptional, and I witnessed true skill, heroism, and compassion. But it also demonstrated to me that a disconnect exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

I see an opportunity here for training to better acclimate responders to working together with our hospital counterparts. We also need hospital personnel to be oriented to realities and limitations of field medicine.

Lt. Brian Pomodoro is a member of the Boston EMS.

NAPLES, FLA. – Without a single life lost at area hospitals, the medical response to the Boston Marathon bombings was by all accounts remarkable. But what if police and other first-responders had tourniquets and were trained in their use?

As it was, advanced topical hemostatic agents and tourniquets were MIA in the field, forcing all but one prehospital tourniquet to be improvised, according to Massachusetts General Hospital trauma surgeon Lt. Col. David King, U. S. Army Reserve.

"It’s abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work," he said. "The fact that every soldier down range has one in his pocket and we couldn’t muster up more than one in the city of Boston is a shame and we need to rectify that."

In all, there were 66 limb injuries, with 29 patients having recognized limb exsanguination at the scene. Of the 27 tourniquets applied, 26 were improvised.

Failure to translate this important lesson from military experience meant that these homemade devices were most likely wildly ineffective and, in some cases, may have even exacerbated blood loss, he said. Surprisingly, there’s no formal protocol for tourniquet application or training paradigm in Massachusetts, such that exists in the Army’s prehospital Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook.

"If you look across the paramedic medical guidelines, there is no protocol on the right, evidence-based way to put on a tourniquet or what the indications are for a tourniquet," Dr. King said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). "We don’t have it, and we need to" have it nationwide.

EAST is hoping to provide some guidance in this area with the development of practice management guidelines (PMG) for tourniquet use in extremity trauma. Dr. King, who heads this PMG committee, reported at the meeting that the guidelines, due out later this year, will emphasize that commercially made tourniquets should be available in the prehospital setting, improvised tourniquets rarely work and cannot be recommended; essentially all commercially made tourniquets are equieffective; and that nonmedical personnel can be trained to correctly apply a proper tourniquet.

The need for bleeding control equipment and training for the public has not gone unnoticed by other stakeholders and is the central focus of the newest statement from the Hartford Consensus, a collaborative group of trauma surgeons, law enforcement officers, and emergency responders led by the American College of Surgeons (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:467-75).

In dissecting the medical response to the Boston bombings, much has been made of the fact that Boston is home to six Level 1 trauma centers, and that it was race day, a city holiday, 3 p.m., and low-yield devices were used. Dr. King, however, gave high praise to an unsung hero, the Boston EMS loading officer who managed most of the transport destination decisions and smartly distributed critical cases throughout the area’s hospitals.

All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some have argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a "stay-and-play" mentality in the medical tent. The after-action review suggests there probably were enough ambulances to do the job in 30 minutes, said Dr. King, who remarked that the only thing that matters in critical trauma cases is time to surgical hemorrhage control.

"This will remain a controversial issue for Boston, whether staying and playing in the medical tent was a good idea," he said. "I don’t know what the right answer is."

Credit was also given to Massachusetts General, and many of the other city hospitals, for their insistence on regular full-scale drills that allowed quick lock-down of the facility to control access and manage the surge capacity in the emergency department.

"It’s more than just a tabletop exercise," Dr. King said. "When we test the surge capacity, we actually empty the emergency room for real. Usually, it occurs between 5:00 and 7:00 or 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning, but actually doing these things was useful, because when it came time to do it for real, no one was tripping over their own feet."

ED volume on that April afternoon was reduced from 97 patients to just 39 within 1.5 hours. Nontrauma physicians, including psychiatrists, did their part by writing "barebones orders" to get patients transferred to the wards.

Staff at Massachusetts General treated 43 patients, performing nine emergent operations, six amputations, two laparotomies, and one thoracotomy, with two traumatic arrests within the first 72 hours. As with other Boston hospitals, there were no in-hospital deaths, he said.

Patients arrived in such rapid succession, however, that it slowed the electronic medical record system and forced staff to use sequential record numbers, which can be dangerous. Registration couldn’t keep up and orders couldn’t be put in fast enough with 43 patients arriving in roughly 35 minutes, Dr. King explained. Workarounds were often old-school, and reminiscent of his days as a green trauma surgeon serving at Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

"In the midst of this entire event, I turned to my nurse practitioner and asked for x, y, z information on a particular patient," he said. "She didn’t turn to her tablet or desktop computer in the operating room. She pulled out a piece of paper where she’d written all the relevant information. At the end of the event, I looked down and realized I’d done the same thing. I was keeping track of my patients on my pants with a Sharpie."

King describes this as a failure of technology and translation from the battlefield, but noted that the hospital did use the military’s practice of reviewing a critical event. Once they’d finished in the operating room and achieved hemorrhage and contamination control, the entire trauma team was reassembled. They did detailed tertiary trauma surveys and went back through every single patient to determine what additional studies they needed, what injuries had been missed.

"It was remarkable the number of things that were missed," Dr. King said. "No one was bleeding to death, but tons and tons of [small, non–life threatening] missed injuries [like ruptured ear drums], and to me this was one of the more important events that surrounded our response to the entire bombing – sitting down after the dust had settled and carefully going over every patient’s medical record."

Dr. King reported having no financial disclosures.

NAPLES, FLA. – Without a single life lost at area hospitals, the medical response to the Boston Marathon bombings was by all accounts remarkable. But what if police and other first-responders had tourniquets and were trained in their use?

As it was, advanced topical hemostatic agents and tourniquets were MIA in the field, forcing all but one prehospital tourniquet to be improvised, according to Massachusetts General Hospital trauma surgeon Lt. Col. David King, U. S. Army Reserve.

"It’s abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work," he said. "The fact that every soldier down range has one in his pocket and we couldn’t muster up more than one in the city of Boston is a shame and we need to rectify that."

In all, there were 66 limb injuries, with 29 patients having recognized limb exsanguination at the scene. Of the 27 tourniquets applied, 26 were improvised.

Failure to translate this important lesson from military experience meant that these homemade devices were most likely wildly ineffective and, in some cases, may have even exacerbated blood loss, he said. Surprisingly, there’s no formal protocol for tourniquet application or training paradigm in Massachusetts, such that exists in the Army’s prehospital Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook.

"If you look across the paramedic medical guidelines, there is no protocol on the right, evidence-based way to put on a tourniquet or what the indications are for a tourniquet," Dr. King said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). "We don’t have it, and we need to" have it nationwide.

EAST is hoping to provide some guidance in this area with the development of practice management guidelines (PMG) for tourniquet use in extremity trauma. Dr. King, who heads this PMG committee, reported at the meeting that the guidelines, due out later this year, will emphasize that commercially made tourniquets should be available in the prehospital setting, improvised tourniquets rarely work and cannot be recommended; essentially all commercially made tourniquets are equieffective; and that nonmedical personnel can be trained to correctly apply a proper tourniquet.

The need for bleeding control equipment and training for the public has not gone unnoticed by other stakeholders and is the central focus of the newest statement from the Hartford Consensus, a collaborative group of trauma surgeons, law enforcement officers, and emergency responders led by the American College of Surgeons (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:467-75).

In dissecting the medical response to the Boston bombings, much has been made of the fact that Boston is home to six Level 1 trauma centers, and that it was race day, a city holiday, 3 p.m., and low-yield devices were used. Dr. King, however, gave high praise to an unsung hero, the Boston EMS loading officer who managed most of the transport destination decisions and smartly distributed critical cases throughout the area’s hospitals.

All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some have argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a "stay-and-play" mentality in the medical tent. The after-action review suggests there probably were enough ambulances to do the job in 30 minutes, said Dr. King, who remarked that the only thing that matters in critical trauma cases is time to surgical hemorrhage control.

"This will remain a controversial issue for Boston, whether staying and playing in the medical tent was a good idea," he said. "I don’t know what the right answer is."

Credit was also given to Massachusetts General, and many of the other city hospitals, for their insistence on regular full-scale drills that allowed quick lock-down of the facility to control access and manage the surge capacity in the emergency department.

"It’s more than just a tabletop exercise," Dr. King said. "When we test the surge capacity, we actually empty the emergency room for real. Usually, it occurs between 5:00 and 7:00 or 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning, but actually doing these things was useful, because when it came time to do it for real, no one was tripping over their own feet."

ED volume on that April afternoon was reduced from 97 patients to just 39 within 1.5 hours. Nontrauma physicians, including psychiatrists, did their part by writing "barebones orders" to get patients transferred to the wards.

Staff at Massachusetts General treated 43 patients, performing nine emergent operations, six amputations, two laparotomies, and one thoracotomy, with two traumatic arrests within the first 72 hours. As with other Boston hospitals, there were no in-hospital deaths, he said.

Patients arrived in such rapid succession, however, that it slowed the electronic medical record system and forced staff to use sequential record numbers, which can be dangerous. Registration couldn’t keep up and orders couldn’t be put in fast enough with 43 patients arriving in roughly 35 minutes, Dr. King explained. Workarounds were often old-school, and reminiscent of his days as a green trauma surgeon serving at Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

"In the midst of this entire event, I turned to my nurse practitioner and asked for x, y, z information on a particular patient," he said. "She didn’t turn to her tablet or desktop computer in the operating room. She pulled out a piece of paper where she’d written all the relevant information. At the end of the event, I looked down and realized I’d done the same thing. I was keeping track of my patients on my pants with a Sharpie."

King describes this as a failure of technology and translation from the battlefield, but noted that the hospital did use the military’s practice of reviewing a critical event. Once they’d finished in the operating room and achieved hemorrhage and contamination control, the entire trauma team was reassembled. They did detailed tertiary trauma surveys and went back through every single patient to determine what additional studies they needed, what injuries had been missed.

"It was remarkable the number of things that were missed," Dr. King said. "No one was bleeding to death, but tons and tons of [small, non–life threatening] missed injuries [like ruptured ear drums], and to me this was one of the more important events that surrounded our response to the entire bombing – sitting down after the dust had settled and carefully going over every patient’s medical record."

Dr. King reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY 2014