User login

In a sample of infants born with microcephaly and a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus, about one-third were found to have vision-threatening eye abnormalities, according to researchers working in a Zika hot spot in Brazil.

The group, led by Dr. Bruno de Paula Freitas of the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, in Salvador, Brazil, evaluated 29 infants with microcephaly born at a single hospital in December following suspected maternal infection with the mosquito-borne Zika virus. In a paper published online Feb 9., Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues reported eye abnormalities in 10 of these children (34.5%) (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267.).

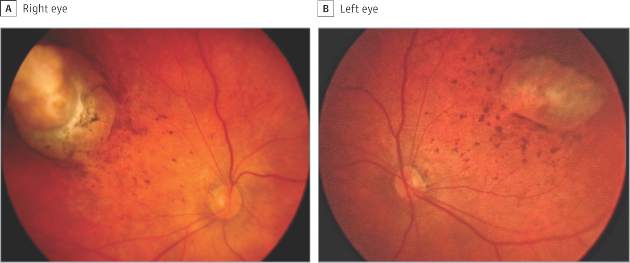

Brazil first reported an outbreak of Zika virus infections in April 2015, followed months later by a spike in the number of infants born with microcephaly, a birth defect defined by a cephalic circumference of 32 cm or less in newborns. The most common ocular abnormalities seen in the cohort of affected infants were pigment mottling of the retina and chorioretinal atrophy (11 of 17 abnormal eyes); optic nerve abnormalities (8 eyes); and iris coloboma (affecting 2 eyes in one infant).

While a previous study of a Zika virus outbreak in Micronesia found conjunctivitis among infected individuals, none of the mothers of the current cohort of infants disclosed having had conjunctivitis. Altogether 23 of the mothers (79%) reported having had any symptoms of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues acknowledged that their results were limited by a small sample size and single-site study design. However, the investigators noted, the findings suggest the possibility “that even oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic pregnant patients presumably infected [with Zika virus] may have microcephalic newborns with ophthalmoscopic lesions” and those newborns should be routinely evaluated for ocular symptoms.

An important question that requires further investigation, they noted, is whether newborns without microcephaly, but whose mothers may have been infected with the Zika virus, should be screened to identify possible ocular lesions.

Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection are not yet well described. The report by de Paula Freitas et al. implicates this infection as the cause of chorioretinal scarring and possibly other ocular abnormalities in infants with microcephaly recently born in Brazil.

Microcephaly can be genetic, metabolic, drug related, or caused by perinatal insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or infection. The present 20-fold reported increase of microcephaly in parts of Brazil is temporally associated with the outbreak of Zika virus. However, this association is still presumptive because definitive serologic testing for Zika virus was not available in Brazil at the time of the outbreak, and confusion may occur with other causes of microcephaly. Similarly, the currently described eye lesions are presumptively associated with the virus.

Based on current information, in our opinion, clinicians in areas where Zika virus is present should perform ophthalmologic examinations on all microcephalic babies. Because it is still unclear whether the eye lesions occur in the absence of microcephaly, it is premature to suggest ophthalmic screening of all babies born in epidemic areas.

Dr. Lee M. Jampol and Dr. Debra A Goldstein are from the department of ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaopthalmol.2016.0284.). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection are not yet well described. The report by de Paula Freitas et al. implicates this infection as the cause of chorioretinal scarring and possibly other ocular abnormalities in infants with microcephaly recently born in Brazil.

Microcephaly can be genetic, metabolic, drug related, or caused by perinatal insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or infection. The present 20-fold reported increase of microcephaly in parts of Brazil is temporally associated with the outbreak of Zika virus. However, this association is still presumptive because definitive serologic testing for Zika virus was not available in Brazil at the time of the outbreak, and confusion may occur with other causes of microcephaly. Similarly, the currently described eye lesions are presumptively associated with the virus.

Based on current information, in our opinion, clinicians in areas where Zika virus is present should perform ophthalmologic examinations on all microcephalic babies. Because it is still unclear whether the eye lesions occur in the absence of microcephaly, it is premature to suggest ophthalmic screening of all babies born in epidemic areas.

Dr. Lee M. Jampol and Dr. Debra A Goldstein are from the department of ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaopthalmol.2016.0284.). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection are not yet well described. The report by de Paula Freitas et al. implicates this infection as the cause of chorioretinal scarring and possibly other ocular abnormalities in infants with microcephaly recently born in Brazil.

Microcephaly can be genetic, metabolic, drug related, or caused by perinatal insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or infection. The present 20-fold reported increase of microcephaly in parts of Brazil is temporally associated with the outbreak of Zika virus. However, this association is still presumptive because definitive serologic testing for Zika virus was not available in Brazil at the time of the outbreak, and confusion may occur with other causes of microcephaly. Similarly, the currently described eye lesions are presumptively associated with the virus.

Based on current information, in our opinion, clinicians in areas where Zika virus is present should perform ophthalmologic examinations on all microcephalic babies. Because it is still unclear whether the eye lesions occur in the absence of microcephaly, it is premature to suggest ophthalmic screening of all babies born in epidemic areas.

Dr. Lee M. Jampol and Dr. Debra A Goldstein are from the department of ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaopthalmol.2016.0284.). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

In a sample of infants born with microcephaly and a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus, about one-third were found to have vision-threatening eye abnormalities, according to researchers working in a Zika hot spot in Brazil.

The group, led by Dr. Bruno de Paula Freitas of the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, in Salvador, Brazil, evaluated 29 infants with microcephaly born at a single hospital in December following suspected maternal infection with the mosquito-borne Zika virus. In a paper published online Feb 9., Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues reported eye abnormalities in 10 of these children (34.5%) (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267.).

Brazil first reported an outbreak of Zika virus infections in April 2015, followed months later by a spike in the number of infants born with microcephaly, a birth defect defined by a cephalic circumference of 32 cm or less in newborns. The most common ocular abnormalities seen in the cohort of affected infants were pigment mottling of the retina and chorioretinal atrophy (11 of 17 abnormal eyes); optic nerve abnormalities (8 eyes); and iris coloboma (affecting 2 eyes in one infant).

While a previous study of a Zika virus outbreak in Micronesia found conjunctivitis among infected individuals, none of the mothers of the current cohort of infants disclosed having had conjunctivitis. Altogether 23 of the mothers (79%) reported having had any symptoms of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues acknowledged that their results were limited by a small sample size and single-site study design. However, the investigators noted, the findings suggest the possibility “that even oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic pregnant patients presumably infected [with Zika virus] may have microcephalic newborns with ophthalmoscopic lesions” and those newborns should be routinely evaluated for ocular symptoms.

An important question that requires further investigation, they noted, is whether newborns without microcephaly, but whose mothers may have been infected with the Zika virus, should be screened to identify possible ocular lesions.

Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

In a sample of infants born with microcephaly and a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus, about one-third were found to have vision-threatening eye abnormalities, according to researchers working in a Zika hot spot in Brazil.

The group, led by Dr. Bruno de Paula Freitas of the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, in Salvador, Brazil, evaluated 29 infants with microcephaly born at a single hospital in December following suspected maternal infection with the mosquito-borne Zika virus. In a paper published online Feb 9., Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues reported eye abnormalities in 10 of these children (34.5%) (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267.).

Brazil first reported an outbreak of Zika virus infections in April 2015, followed months later by a spike in the number of infants born with microcephaly, a birth defect defined by a cephalic circumference of 32 cm or less in newborns. The most common ocular abnormalities seen in the cohort of affected infants were pigment mottling of the retina and chorioretinal atrophy (11 of 17 abnormal eyes); optic nerve abnormalities (8 eyes); and iris coloboma (affecting 2 eyes in one infant).

While a previous study of a Zika virus outbreak in Micronesia found conjunctivitis among infected individuals, none of the mothers of the current cohort of infants disclosed having had conjunctivitis. Altogether 23 of the mothers (79%) reported having had any symptoms of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues acknowledged that their results were limited by a small sample size and single-site study design. However, the investigators noted, the findings suggest the possibility “that even oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic pregnant patients presumably infected [with Zika virus] may have microcephalic newborns with ophthalmoscopic lesions” and those newborns should be routinely evaluated for ocular symptoms.

An important question that requires further investigation, they noted, is whether newborns without microcephaly, but whose mothers may have been infected with the Zika virus, should be screened to identify possible ocular lesions.

Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA OPTHALMOLOGY

Key clinical point: Serious ocular abnormalities may accompany microcephaly in babies born to mothers infected with the Zika virus.

Major finding: More than one-third (34.5%) of a cohort of 29 infants born with microcephaly and with a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus had ocular abnormalities in one or both eyes.

Data source: A single-site cohort study evaluating 29 infants born with microcephaly in a single hospital in Salvador, Brazil.

Disclosures: Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.