User login

- If a patient does not exhibit any of the criteria of the Ottawa Ankle Rules, radiographs of the foot or ankle are unnecessary (SOR: A).

- Discuss the history, exam findings, and Ottawa Rules with patients. Evidence suggests that satisfaction with care does not depend on whether radiographs are ordered (SOR: B).

In the United States, most ankle injuries are evaluated radiographically, 1,2 even though only about 15% are found to involve fractures. 3 An estimated 6 million ankle radiographs are performed annually in the US and Canada, costing approximately $300 million dollars (US). The Ottawa Ankle Rules can significantly decrease the number of unnecessary ankle radiographs.

The rules are not a substitute for sound clinical judgment, but augment findings in the history and physical examination to help the clinician determine the appropriateness of ankle films. If the rules are met and radiographs are avoided, it is unlikely, especially with good communication and follow-up, that a patient will turn out to have a significant fracture. Moreover, discussing physical examination findings and the reasons for doing or not doing radiographs will enhance patient-physician communication. As we report in this article, patients’ satisfaction with care seems not to depend on whether x-ray films are ordered.

Applying the Ottawa Ankle Rules

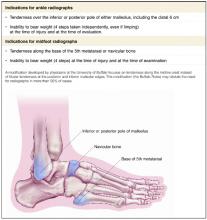

To address the problem of low positive predictive value of ankle radiographs, Stiell and colleagues4 at the University of Ottawa and the Ontario Health Ministry developed a set of clinical parameters in the early 1990s to evaluate the need for ankle and midfoot radiographs. Their criteria were based on a multivariable data analysis involving a large number of clinical variables associated with ankle injuries. The resulting rules (Figure) have been shown to decrease the need for films by about 30%.4 If a patient does not exhibit any of the criteria, radiographs of the foot or ankle are not needed after trauma (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

FIGURE

Ottawa Ankle Rules for determining the need for radiographs Indications for ankle radiographs

Validation of the rules in different settings

A number of studies have tested the negative predictive value of the Ottawa Ankle Rules. A high negative predictive value implies that if the rules are followed, a fracture will not be missed. Most of these studies were conducted in emergency medicine, sports medicine, and orthopedic settings. In a follow-up study, Stiell and colleagues found a sensitivity of 1.0 (95% confidence interval, 0.95–1.0) for ankle fractures and mid-foot fractures. A positive result is a clinically significant fracture, described as one greater than 3 mm. Such avulsion type injuries are treated clinically like a sprain. In the Stiell study, all films were evaluated by radiologists. The authors estimated a decrease in ankle radiographs by 28% if the rules were followed.4

Emergency medicine. The sensitivity in this setting was also found to be 1.0, with a negative predictive value of 1.0 when used by physicians. This means that no fractures would be missed by using the rules. Specificity was only 0.19.3 In a multicenter Canadian trial, the results were similar. Over 12,000 adults were evaluated with the ankle rule at 8 teaching and community hospital emergency departments. This study found a significant decrease in the number of ankle radiographs ordered without an increase in the rate of fractures missed.5

Orthopedic surgery. In a study involving 153 military cadets at West Point, orthopedic surgeons also showed the sensitivity of these rules was 1.0, with no false negatives. The investigators estimated they could safely forego 40% of all ankle films and 79% of all midfoot films. In the 4 years of training at the Military Academy, an estimated 33% of all cadets suffer an ankle sprain, which speaks to the prevalence of this condition among young, active persons.4

Sports medicine. A prospective study in a university sports medicine clinic validated the use of the ankle rules in a population of 94 athletes. The investigators found a sensitivity of 1.0 for both ankle and midfoot injuries, and a reduction by 34% in the number of films ordered.7 In that study the authors comment on the value of these rules in the sports medicine venue, where the rate of ankle and midfoot fractures is low (less than 3%, as opposed to up to 20% in the emergency setting).8

Family medicine. Little research in family medicine discusses office use of the Ottawa Ankle Rules, but there is a need for a set of evidence-based protocols in evaluating acute ankle injuries. Before establishment of the ankle rules, family physicians used the clinical findings of (1) absence of tenderness on the dorsum of the foot, (2) lack of impaired weight bearing, (3) recentness of injury (more than 12 hours earlier), and (4) absence of additional injuries. Each of these findings had a negative predictive value of least 94%. While family physician researchers involved in one study did not establish a set of decision “rules,” they estimated that using these criteria could reduce unnecessary films by about 30%.9

Meta-analysis. To synthesize results from a large number of studies of the Ottawa Ankle Rules, a meta-analysis involving 27 studies including over 15,000 patients found that evidence supported the rules as an instrument for clinically excluding fractures of the ankle and midfoot. This analysis noted the sensitivity of 1.0 found in virtually every study and estimated that the Ottawa Ankle Rules would decrease the need for films by 30% to 40%.10

The Ottawa Ankle Rules and children

The original Ottawa Ankle Rules were applied strictly to adults, but they also have been studied considerably in the care of children. Pediatric studies have documented sensitivities ranging from 97% to 100% and specificities from 24% to 47%. All studies have shown significant decreases in unnecessary films and significant cost savings. The conclusion of all authors was that the Ottawa Ankle Rules are a cost-effective, highly sensitive test for evaluating acute ankle injuries in children. 11-14

However, researchers at the University of Colorado prospectively evaluated the use of Ottawa Ankle Rules in children aged <18 years. The previous studies had used the same criteria as used for adults, but because of the uncertainty of the long-term effects of Salter I (epiphyseal injury) or small (<3 mm) avulsion fractures in the pediatric population, those injuries were included in the fracture category. This brought the sensitivity down to 83%, with a negative predictive value of 93%. The authors suggested that the Ottawa Rules not be employed in the pediatric population.15 Clearly, more work needs to be done in order to clear them for use in children.

Using the rules reduces costs

Researchers analyzed the cost effectiveness of the rules in the US.16 Variables used to estimate savings included waiting time and lost productivity as well as the obvious medical and radiographic costs. Previous studies have indicated at least a 28% decrease in unneeded ankle films.4 By using this admittedly conservative reduction, it was estimated that the savings would range from $18 to $90 million annually (depending on payer mix involved). Even the smaller amount represents a significant cost savings.

Rule modifications could increase specificity

Because of the low specificity of the Ottawa Rules (a large number of false-positive results are still obtained), sports medicine physicians at the University of Buffalo determined that a modified set of ankle rules could increase specificity significantly. These rules, called the “Buffalo Rules,” kept most of the original rules but changed the original area of fibular tenderness from the posterior and inferior malleolar edges to the midline crest. Using this modification maintained the high sensitivity of the original rules and decreased the need for radiographs from 34% to over 50% (SOR: B).7

Patient satisfaction not dependent on films

While most radiographs done for acute ankle injuries are not helpful, many physicians believe patients expect them and will be dissatisfied or upset if films are not taken. A recent Canadian study evaluated the claim that patient preferences influenced physician test ordering and compliance with clinical guidelines. Specifically it looked at emergency department implementation of the Ottawa Ankle Rules and patient satisfaction.17

This study of almost 1000 patients, split between a population who received films and those who did not for an acute ankle or midfoot injury, indicated that patients who did not get radiographs were just as satisfied with their care as those that did. In the study, 76% of physicians supported the use of clinical guidelines, but 78% admitted that patient expectations influenced their decision making. These rules would likely be of great value where radiographic facilities are inconvenient or costly for patients.

Correspondence

Dr. Paul J. Nugent, 4411 Montgomery Rd, Suite 200, Cincinnati, Ohio 45212. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Dunlop MG, Beattie TF, White GK, Raab GM, Doull RI. Guidelines for selective radiologic assessment of inversion ankle injuries. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:603-605.

2. Vargish T, Clarke WR. The ankle injury: indication for selective use of X-rays. Injury 1983;14:507-512.

3. Pigman EC, Klug RK, Sanford S, Jolly BT. Evaluation of the Ottawa clinical decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle and midfoot injuries in the emergency department: an independent site assessment. Ann Emerg Med 1994;24:41-45.

4. Stiell IG, McKnight RD, Greenberg GH, et al. Implementation of the Ottawa Ankle Rules. JAMA 1994;271:827-832.

5. McBride KL. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules. Experience at a community hospital. Can Fam Physician 1997;43:459-465.

6. Springer, Arciero RA, Tenuta JJ, Taylor DC. A prospective study of modified Ottawa ankle rule in a military population. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:864-868.

7. Leddy JL, Smolinski RJ, Lawrence J, Snyder JL, Priore RL. Prospective evaluation of the Ottawa ankle rules in a university sports medicine center. With a modification to increase specificity for identifying malleolar fractures. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:158-165.

8. Garrick JG. Epidemiological perspective. Clin Sports Med 1982;1:13-18.

9. Smith GF, Madlon-Kay DJ, Hunt V. Clinical inversion injuries in family practice offices. J Fam Pract 1993;37:345-348.

10. Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, ter Riet G. Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fracture of the ankle and midfoot: systematic review. BMJ 2003;326:417.-

11. Chande VT. Decision rules for roentgenography of children with acute ankle injuries. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:255-258.

12. Karpas A, Hennes H, Walsh-Kelly C. Utilization of the Ottawa ankle rules by nurses in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:130-133.

13. Libetta C, Burke D, Brennan P, Yassa J. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules in children. J Accid Emerg Med 1999;16:342-344.

14. Plint AC, Bulloch B, Osmond MH, et al. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules in children with ankle injuries. Acad Emerg Med 1999;6:1005-1009.

15. Clark KD, Tanner S. Evaluation of the Ottawa ankle rules in children. Pedriatr Emerg Care 2003;19:73-78.

16. Anis AH, Stiell IG, Stewart DG, Laupacis A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the Ottawa ankle rules. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:422-428.

17. Wilson DE, Noseworthy TW, Rowe BH, Holroyd BR. Evaluation of patient satisfaction and outcomes after assessment for acute ankle injuries. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:18-22.

- If a patient does not exhibit any of the criteria of the Ottawa Ankle Rules, radiographs of the foot or ankle are unnecessary (SOR: A).

- Discuss the history, exam findings, and Ottawa Rules with patients. Evidence suggests that satisfaction with care does not depend on whether radiographs are ordered (SOR: B).

In the United States, most ankle injuries are evaluated radiographically, 1,2 even though only about 15% are found to involve fractures. 3 An estimated 6 million ankle radiographs are performed annually in the US and Canada, costing approximately $300 million dollars (US). The Ottawa Ankle Rules can significantly decrease the number of unnecessary ankle radiographs.

The rules are not a substitute for sound clinical judgment, but augment findings in the history and physical examination to help the clinician determine the appropriateness of ankle films. If the rules are met and radiographs are avoided, it is unlikely, especially with good communication and follow-up, that a patient will turn out to have a significant fracture. Moreover, discussing physical examination findings and the reasons for doing or not doing radiographs will enhance patient-physician communication. As we report in this article, patients’ satisfaction with care seems not to depend on whether x-ray films are ordered.

Applying the Ottawa Ankle Rules

To address the problem of low positive predictive value of ankle radiographs, Stiell and colleagues4 at the University of Ottawa and the Ontario Health Ministry developed a set of clinical parameters in the early 1990s to evaluate the need for ankle and midfoot radiographs. Their criteria were based on a multivariable data analysis involving a large number of clinical variables associated with ankle injuries. The resulting rules (Figure) have been shown to decrease the need for films by about 30%.4 If a patient does not exhibit any of the criteria, radiographs of the foot or ankle are not needed after trauma (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

FIGURE

Ottawa Ankle Rules for determining the need for radiographs Indications for ankle radiographs

Validation of the rules in different settings

A number of studies have tested the negative predictive value of the Ottawa Ankle Rules. A high negative predictive value implies that if the rules are followed, a fracture will not be missed. Most of these studies were conducted in emergency medicine, sports medicine, and orthopedic settings. In a follow-up study, Stiell and colleagues found a sensitivity of 1.0 (95% confidence interval, 0.95–1.0) for ankle fractures and mid-foot fractures. A positive result is a clinically significant fracture, described as one greater than 3 mm. Such avulsion type injuries are treated clinically like a sprain. In the Stiell study, all films were evaluated by radiologists. The authors estimated a decrease in ankle radiographs by 28% if the rules were followed.4

Emergency medicine. The sensitivity in this setting was also found to be 1.0, with a negative predictive value of 1.0 when used by physicians. This means that no fractures would be missed by using the rules. Specificity was only 0.19.3 In a multicenter Canadian trial, the results were similar. Over 12,000 adults were evaluated with the ankle rule at 8 teaching and community hospital emergency departments. This study found a significant decrease in the number of ankle radiographs ordered without an increase in the rate of fractures missed.5

Orthopedic surgery. In a study involving 153 military cadets at West Point, orthopedic surgeons also showed the sensitivity of these rules was 1.0, with no false negatives. The investigators estimated they could safely forego 40% of all ankle films and 79% of all midfoot films. In the 4 years of training at the Military Academy, an estimated 33% of all cadets suffer an ankle sprain, which speaks to the prevalence of this condition among young, active persons.4

Sports medicine. A prospective study in a university sports medicine clinic validated the use of the ankle rules in a population of 94 athletes. The investigators found a sensitivity of 1.0 for both ankle and midfoot injuries, and a reduction by 34% in the number of films ordered.7 In that study the authors comment on the value of these rules in the sports medicine venue, where the rate of ankle and midfoot fractures is low (less than 3%, as opposed to up to 20% in the emergency setting).8

Family medicine. Little research in family medicine discusses office use of the Ottawa Ankle Rules, but there is a need for a set of evidence-based protocols in evaluating acute ankle injuries. Before establishment of the ankle rules, family physicians used the clinical findings of (1) absence of tenderness on the dorsum of the foot, (2) lack of impaired weight bearing, (3) recentness of injury (more than 12 hours earlier), and (4) absence of additional injuries. Each of these findings had a negative predictive value of least 94%. While family physician researchers involved in one study did not establish a set of decision “rules,” they estimated that using these criteria could reduce unnecessary films by about 30%.9

Meta-analysis. To synthesize results from a large number of studies of the Ottawa Ankle Rules, a meta-analysis involving 27 studies including over 15,000 patients found that evidence supported the rules as an instrument for clinically excluding fractures of the ankle and midfoot. This analysis noted the sensitivity of 1.0 found in virtually every study and estimated that the Ottawa Ankle Rules would decrease the need for films by 30% to 40%.10

The Ottawa Ankle Rules and children

The original Ottawa Ankle Rules were applied strictly to adults, but they also have been studied considerably in the care of children. Pediatric studies have documented sensitivities ranging from 97% to 100% and specificities from 24% to 47%. All studies have shown significant decreases in unnecessary films and significant cost savings. The conclusion of all authors was that the Ottawa Ankle Rules are a cost-effective, highly sensitive test for evaluating acute ankle injuries in children. 11-14

However, researchers at the University of Colorado prospectively evaluated the use of Ottawa Ankle Rules in children aged <18 years. The previous studies had used the same criteria as used for adults, but because of the uncertainty of the long-term effects of Salter I (epiphyseal injury) or small (<3 mm) avulsion fractures in the pediatric population, those injuries were included in the fracture category. This brought the sensitivity down to 83%, with a negative predictive value of 93%. The authors suggested that the Ottawa Rules not be employed in the pediatric population.15 Clearly, more work needs to be done in order to clear them for use in children.

Using the rules reduces costs

Researchers analyzed the cost effectiveness of the rules in the US.16 Variables used to estimate savings included waiting time and lost productivity as well as the obvious medical and radiographic costs. Previous studies have indicated at least a 28% decrease in unneeded ankle films.4 By using this admittedly conservative reduction, it was estimated that the savings would range from $18 to $90 million annually (depending on payer mix involved). Even the smaller amount represents a significant cost savings.

Rule modifications could increase specificity

Because of the low specificity of the Ottawa Rules (a large number of false-positive results are still obtained), sports medicine physicians at the University of Buffalo determined that a modified set of ankle rules could increase specificity significantly. These rules, called the “Buffalo Rules,” kept most of the original rules but changed the original area of fibular tenderness from the posterior and inferior malleolar edges to the midline crest. Using this modification maintained the high sensitivity of the original rules and decreased the need for radiographs from 34% to over 50% (SOR: B).7

Patient satisfaction not dependent on films

While most radiographs done for acute ankle injuries are not helpful, many physicians believe patients expect them and will be dissatisfied or upset if films are not taken. A recent Canadian study evaluated the claim that patient preferences influenced physician test ordering and compliance with clinical guidelines. Specifically it looked at emergency department implementation of the Ottawa Ankle Rules and patient satisfaction.17

This study of almost 1000 patients, split between a population who received films and those who did not for an acute ankle or midfoot injury, indicated that patients who did not get radiographs were just as satisfied with their care as those that did. In the study, 76% of physicians supported the use of clinical guidelines, but 78% admitted that patient expectations influenced their decision making. These rules would likely be of great value where radiographic facilities are inconvenient or costly for patients.

Correspondence

Dr. Paul J. Nugent, 4411 Montgomery Rd, Suite 200, Cincinnati, Ohio 45212. E-mail: [email protected].

- If a patient does not exhibit any of the criteria of the Ottawa Ankle Rules, radiographs of the foot or ankle are unnecessary (SOR: A).

- Discuss the history, exam findings, and Ottawa Rules with patients. Evidence suggests that satisfaction with care does not depend on whether radiographs are ordered (SOR: B).

In the United States, most ankle injuries are evaluated radiographically, 1,2 even though only about 15% are found to involve fractures. 3 An estimated 6 million ankle radiographs are performed annually in the US and Canada, costing approximately $300 million dollars (US). The Ottawa Ankle Rules can significantly decrease the number of unnecessary ankle radiographs.

The rules are not a substitute for sound clinical judgment, but augment findings in the history and physical examination to help the clinician determine the appropriateness of ankle films. If the rules are met and radiographs are avoided, it is unlikely, especially with good communication and follow-up, that a patient will turn out to have a significant fracture. Moreover, discussing physical examination findings and the reasons for doing or not doing radiographs will enhance patient-physician communication. As we report in this article, patients’ satisfaction with care seems not to depend on whether x-ray films are ordered.

Applying the Ottawa Ankle Rules

To address the problem of low positive predictive value of ankle radiographs, Stiell and colleagues4 at the University of Ottawa and the Ontario Health Ministry developed a set of clinical parameters in the early 1990s to evaluate the need for ankle and midfoot radiographs. Their criteria were based on a multivariable data analysis involving a large number of clinical variables associated with ankle injuries. The resulting rules (Figure) have been shown to decrease the need for films by about 30%.4 If a patient does not exhibit any of the criteria, radiographs of the foot or ankle are not needed after trauma (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

FIGURE

Ottawa Ankle Rules for determining the need for radiographs Indications for ankle radiographs

Validation of the rules in different settings

A number of studies have tested the negative predictive value of the Ottawa Ankle Rules. A high negative predictive value implies that if the rules are followed, a fracture will not be missed. Most of these studies were conducted in emergency medicine, sports medicine, and orthopedic settings. In a follow-up study, Stiell and colleagues found a sensitivity of 1.0 (95% confidence interval, 0.95–1.0) for ankle fractures and mid-foot fractures. A positive result is a clinically significant fracture, described as one greater than 3 mm. Such avulsion type injuries are treated clinically like a sprain. In the Stiell study, all films were evaluated by radiologists. The authors estimated a decrease in ankle radiographs by 28% if the rules were followed.4

Emergency medicine. The sensitivity in this setting was also found to be 1.0, with a negative predictive value of 1.0 when used by physicians. This means that no fractures would be missed by using the rules. Specificity was only 0.19.3 In a multicenter Canadian trial, the results were similar. Over 12,000 adults were evaluated with the ankle rule at 8 teaching and community hospital emergency departments. This study found a significant decrease in the number of ankle radiographs ordered without an increase in the rate of fractures missed.5

Orthopedic surgery. In a study involving 153 military cadets at West Point, orthopedic surgeons also showed the sensitivity of these rules was 1.0, with no false negatives. The investigators estimated they could safely forego 40% of all ankle films and 79% of all midfoot films. In the 4 years of training at the Military Academy, an estimated 33% of all cadets suffer an ankle sprain, which speaks to the prevalence of this condition among young, active persons.4

Sports medicine. A prospective study in a university sports medicine clinic validated the use of the ankle rules in a population of 94 athletes. The investigators found a sensitivity of 1.0 for both ankle and midfoot injuries, and a reduction by 34% in the number of films ordered.7 In that study the authors comment on the value of these rules in the sports medicine venue, where the rate of ankle and midfoot fractures is low (less than 3%, as opposed to up to 20% in the emergency setting).8

Family medicine. Little research in family medicine discusses office use of the Ottawa Ankle Rules, but there is a need for a set of evidence-based protocols in evaluating acute ankle injuries. Before establishment of the ankle rules, family physicians used the clinical findings of (1) absence of tenderness on the dorsum of the foot, (2) lack of impaired weight bearing, (3) recentness of injury (more than 12 hours earlier), and (4) absence of additional injuries. Each of these findings had a negative predictive value of least 94%. While family physician researchers involved in one study did not establish a set of decision “rules,” they estimated that using these criteria could reduce unnecessary films by about 30%.9

Meta-analysis. To synthesize results from a large number of studies of the Ottawa Ankle Rules, a meta-analysis involving 27 studies including over 15,000 patients found that evidence supported the rules as an instrument for clinically excluding fractures of the ankle and midfoot. This analysis noted the sensitivity of 1.0 found in virtually every study and estimated that the Ottawa Ankle Rules would decrease the need for films by 30% to 40%.10

The Ottawa Ankle Rules and children

The original Ottawa Ankle Rules were applied strictly to adults, but they also have been studied considerably in the care of children. Pediatric studies have documented sensitivities ranging from 97% to 100% and specificities from 24% to 47%. All studies have shown significant decreases in unnecessary films and significant cost savings. The conclusion of all authors was that the Ottawa Ankle Rules are a cost-effective, highly sensitive test for evaluating acute ankle injuries in children. 11-14

However, researchers at the University of Colorado prospectively evaluated the use of Ottawa Ankle Rules in children aged <18 years. The previous studies had used the same criteria as used for adults, but because of the uncertainty of the long-term effects of Salter I (epiphyseal injury) or small (<3 mm) avulsion fractures in the pediatric population, those injuries were included in the fracture category. This brought the sensitivity down to 83%, with a negative predictive value of 93%. The authors suggested that the Ottawa Rules not be employed in the pediatric population.15 Clearly, more work needs to be done in order to clear them for use in children.

Using the rules reduces costs

Researchers analyzed the cost effectiveness of the rules in the US.16 Variables used to estimate savings included waiting time and lost productivity as well as the obvious medical and radiographic costs. Previous studies have indicated at least a 28% decrease in unneeded ankle films.4 By using this admittedly conservative reduction, it was estimated that the savings would range from $18 to $90 million annually (depending on payer mix involved). Even the smaller amount represents a significant cost savings.

Rule modifications could increase specificity

Because of the low specificity of the Ottawa Rules (a large number of false-positive results are still obtained), sports medicine physicians at the University of Buffalo determined that a modified set of ankle rules could increase specificity significantly. These rules, called the “Buffalo Rules,” kept most of the original rules but changed the original area of fibular tenderness from the posterior and inferior malleolar edges to the midline crest. Using this modification maintained the high sensitivity of the original rules and decreased the need for radiographs from 34% to over 50% (SOR: B).7

Patient satisfaction not dependent on films

While most radiographs done for acute ankle injuries are not helpful, many physicians believe patients expect them and will be dissatisfied or upset if films are not taken. A recent Canadian study evaluated the claim that patient preferences influenced physician test ordering and compliance with clinical guidelines. Specifically it looked at emergency department implementation of the Ottawa Ankle Rules and patient satisfaction.17

This study of almost 1000 patients, split between a population who received films and those who did not for an acute ankle or midfoot injury, indicated that patients who did not get radiographs were just as satisfied with their care as those that did. In the study, 76% of physicians supported the use of clinical guidelines, but 78% admitted that patient expectations influenced their decision making. These rules would likely be of great value where radiographic facilities are inconvenient or costly for patients.

Correspondence

Dr. Paul J. Nugent, 4411 Montgomery Rd, Suite 200, Cincinnati, Ohio 45212. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Dunlop MG, Beattie TF, White GK, Raab GM, Doull RI. Guidelines for selective radiologic assessment of inversion ankle injuries. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:603-605.

2. Vargish T, Clarke WR. The ankle injury: indication for selective use of X-rays. Injury 1983;14:507-512.

3. Pigman EC, Klug RK, Sanford S, Jolly BT. Evaluation of the Ottawa clinical decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle and midfoot injuries in the emergency department: an independent site assessment. Ann Emerg Med 1994;24:41-45.

4. Stiell IG, McKnight RD, Greenberg GH, et al. Implementation of the Ottawa Ankle Rules. JAMA 1994;271:827-832.

5. McBride KL. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules. Experience at a community hospital. Can Fam Physician 1997;43:459-465.

6. Springer, Arciero RA, Tenuta JJ, Taylor DC. A prospective study of modified Ottawa ankle rule in a military population. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:864-868.

7. Leddy JL, Smolinski RJ, Lawrence J, Snyder JL, Priore RL. Prospective evaluation of the Ottawa ankle rules in a university sports medicine center. With a modification to increase specificity for identifying malleolar fractures. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:158-165.

8. Garrick JG. Epidemiological perspective. Clin Sports Med 1982;1:13-18.

9. Smith GF, Madlon-Kay DJ, Hunt V. Clinical inversion injuries in family practice offices. J Fam Pract 1993;37:345-348.

10. Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, ter Riet G. Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fracture of the ankle and midfoot: systematic review. BMJ 2003;326:417.-

11. Chande VT. Decision rules for roentgenography of children with acute ankle injuries. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:255-258.

12. Karpas A, Hennes H, Walsh-Kelly C. Utilization of the Ottawa ankle rules by nurses in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:130-133.

13. Libetta C, Burke D, Brennan P, Yassa J. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules in children. J Accid Emerg Med 1999;16:342-344.

14. Plint AC, Bulloch B, Osmond MH, et al. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules in children with ankle injuries. Acad Emerg Med 1999;6:1005-1009.

15. Clark KD, Tanner S. Evaluation of the Ottawa ankle rules in children. Pedriatr Emerg Care 2003;19:73-78.

16. Anis AH, Stiell IG, Stewart DG, Laupacis A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the Ottawa ankle rules. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:422-428.

17. Wilson DE, Noseworthy TW, Rowe BH, Holroyd BR. Evaluation of patient satisfaction and outcomes after assessment for acute ankle injuries. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:18-22.

1. Dunlop MG, Beattie TF, White GK, Raab GM, Doull RI. Guidelines for selective radiologic assessment of inversion ankle injuries. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:603-605.

2. Vargish T, Clarke WR. The ankle injury: indication for selective use of X-rays. Injury 1983;14:507-512.

3. Pigman EC, Klug RK, Sanford S, Jolly BT. Evaluation of the Ottawa clinical decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle and midfoot injuries in the emergency department: an independent site assessment. Ann Emerg Med 1994;24:41-45.

4. Stiell IG, McKnight RD, Greenberg GH, et al. Implementation of the Ottawa Ankle Rules. JAMA 1994;271:827-832.

5. McBride KL. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules. Experience at a community hospital. Can Fam Physician 1997;43:459-465.

6. Springer, Arciero RA, Tenuta JJ, Taylor DC. A prospective study of modified Ottawa ankle rule in a military population. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:864-868.

7. Leddy JL, Smolinski RJ, Lawrence J, Snyder JL, Priore RL. Prospective evaluation of the Ottawa ankle rules in a university sports medicine center. With a modification to increase specificity for identifying malleolar fractures. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:158-165.

8. Garrick JG. Epidemiological perspective. Clin Sports Med 1982;1:13-18.

9. Smith GF, Madlon-Kay DJ, Hunt V. Clinical inversion injuries in family practice offices. J Fam Pract 1993;37:345-348.

10. Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, ter Riet G. Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fracture of the ankle and midfoot: systematic review. BMJ 2003;326:417.-

11. Chande VT. Decision rules for roentgenography of children with acute ankle injuries. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:255-258.

12. Karpas A, Hennes H, Walsh-Kelly C. Utilization of the Ottawa ankle rules by nurses in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:130-133.

13. Libetta C, Burke D, Brennan P, Yassa J. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules in children. J Accid Emerg Med 1999;16:342-344.

14. Plint AC, Bulloch B, Osmond MH, et al. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules in children with ankle injuries. Acad Emerg Med 1999;6:1005-1009.

15. Clark KD, Tanner S. Evaluation of the Ottawa ankle rules in children. Pedriatr Emerg Care 2003;19:73-78.

16. Anis AH, Stiell IG, Stewart DG, Laupacis A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the Ottawa ankle rules. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:422-428.

17. Wilson DE, Noseworthy TW, Rowe BH, Holroyd BR. Evaluation of patient satisfaction and outcomes after assessment for acute ankle injuries. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:18-22.