User login

Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) has been suggested as a parallel pyogenic infection to acute otitis media (AOM). Like AOM, ABRS is due to obstruction of the normal drainage system into the nasopharynx from a normally aerated pouch(es) within the bone of the skull. Potential pathogens from the nasopharynx, having refluxed into the aerated spaces, begin to replicate and induce inflammation, at least in part due to the obstruction and the inflammation-induced deficiency of the normal cleansing system. For the middle ear, this system is the eustachian tube complex. For the sinuses, it is the osteomeatal complex. The similarities have led some to designate ABRS as "AOM in the middle of the face."

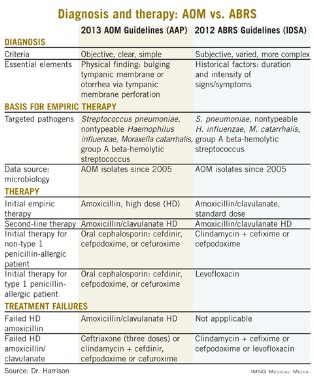

Other parallels are striking, including the microbiology, although 21st century data are less available for the microbiology of ABRS compared with AOM. The table lists some comparisons between the 2013 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines on managing AOM (Pediatrics 2013;131;e964-e999) and the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) ABRS guidelines (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:e72-e112).

So the question arises: Why was high-dose amoxicillin reaffirmed as the drug of choice for uncomplicated AOM in normal hosts in the 2013 AAP AOM guidelines, whereas the most recent guidelines for ABRS (2012 from IDSA) recommend standard-dose amoxicillin plus clavulanate? Amoxicillin is an inexpensive and reasonably palatable drug with a low adverse effect (AE) profile. Amoxicillin-clavulanate is a broader-spectrum, more expensive, somewhat bitter-tasting drug with a moderate AE profile. When the extra spectrum is needed, the added expense and AEs are acceptable. But they seem excessive for a first-line drug.

Do differences in diagnostic criteria lessen the impact on antimicrobial resistance from use of a broader-spectrum first-line drug for ABRS compared to AOM?

Compared with the 2013 AAP otitis media guidelines, which provide objective, clear, and simple criteria, the 2012 IDSA ABRS Guidelines have less objective and less precise criteria. For an AOM diagnosis, the tympanic membrane (TM) must be bulging or be perforated with purulent drainage. Both result from an expanding inflammatory process that stretches the TM. Using this single criterion in the presence of an effusion, clinicians have a clear understanding of what constitutes AOM. No more need to rely on history of acute onset, or a particular color or opacity, or lack of mobility on pneumatic otoscopy. One need only see a bulging TM and note that there is an inflammatory effusion. Bingo – this is AOM.

So, diagnosis of AOM is easier and can be more precise, eliminating "uncertain AOM" from the options. With these firm diagnostic criteria, the question then is whether the AOM episode requires antibiotics. That question is also addressed in the 2013 guidelines and will not be discussed here. The end result is that the 2013 AOM guidelines should decrease the number of AOM diagnoses and thereby antibiotic overuse.

Based on the 2012 IDSA Guideline for ABRS, in contrast, there are three sets of circumstances whereby an ABRS diagnosis can be made. For the most part these involve historical data about duration and intensity of symptoms reported by patients or parents. Thus these are varied, mostly subjective, and more complex with multiple nuances. There is more art and no real reliance on objective physical findings in diagnosing ABRS. This is due to there being no reliable physical findings to diagnose uncomplicated ABRS. There also is no reliable, inexpensive, and safe laboratory or radiological modality for ABRS diagnosis. This results in considerable wiggle room and subjective clinical judgment about the diagnosis.

And the 2012 IDSA ABRS guidelines state that antibiotic treatment should begin whenever an ABRS diagnosis is made. There is some verbiage that one could consider observation without antibiotics if the symptoms are mild, but there are no specifics about what constitutes "mild." This seems like the perfect storm for potential overdiagnosis and overuse of antibiotics, so a broader-spectrum drug would be less desirable from an antibiotic stewardship perspective.

Are pathogens in routine uncomplicated ABRS more resistant to amoxicillin than in AOM so that addition of clavulanate to neutralize beta-lactamase is warranted?

The 2012 ABRS guidelines indicate that the basis for recommending amoxicillin-clavulanate was the microbiology of AOM. There has been little pediatric ABRS microbiology in the past 25 years because sinus punctures are needed to have the best data. Such punctures have not been used in controlled trials in decades. So it is logical to use AOM data, given that pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) have produced shifts in pneumococcal serotypes, and there continues to be an evolving distribution of serotypes and their accompanying antibiotic resistance patterns since the 2010 shift to PCV13.

The current expectation is that serotype 19A, the most frequently multidrug-resistant serotype that emerged after PCV7 was introduced in 2000, will decline by the end of 2013. Other classic pneumococcal otopathogen serotypes expressing resistance to amoxicillin have declined since 2004, as has the overall prevalence of AOM due to pneumococcus. Since 2004, more than 50% of recently antibiotic-treated or recurrent AOM appear to be due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (ntHi), and more than half of these produce beta-lactamase. (Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004;23:829-33; Pediatr. Infect Dis. J. 2010;29:304-9). So more than 25% of recently antibiotic-treated AOM patients would be expected to have amoxicillin-resistant pathogens by virtue of beta-lactamase.

Is this a reasonable rationale for the first-line therapy for both AOM and ABRS to be standard (some would call low) dose, but beta-lactamase stable, amoxicillin-clavulanate at 45 mg/kg per day divided twice daily? This is the argument utilized in the 2012 IDSA ABRS guidelines. However, based on the same data, the AAP 2013 AOM guidelines conclude that high-dose amoxicillin without clavulanate should be used for first-line empiric therapy of AOM.

A powerful argument for the AAP AOM guidelines is the expectation that half of all ntHi, including those that produce beta-lactamase, will spontaneously clear without antibiotics. This is more frequent than for pneumococcus, which has only a 20% spontaneous remission. Data from our laboratory in Kansas City showed that up to 50% of the ntHi in persistent or recurrent AOM produce beta-lactamase; however, less than 15% do so in AOM when not recently treated with antibiotics (Harrison, C.J. The Changing Microbiology of Acute Otitis Media, in "Acute Otitis Media: Translating Science into Clinical Practice," International Congress and Symposium Series. 265:22-35. Royal Society of Medicine Press, London, 2007). How powerful then is the argument to add clavulanate and to use low-dose amoxicillin?

ntHi considered

First consider the contribution to amoxicillin failures by ntHi. Choosing a worst-case scenario of all ABRS having the microbiology of recently treated AOM, we will assume that 60% of persistent/recurrent AOM (and by extrapolation ABRS) is due to ntHi, and 50% of these produce beta-lactamase. Now factor in that 50% of all ntHi clear without antibiotics. The overall expected clinical failure rate for amoxicillin due to beta-lactamase producing ntHi in recurrent/persistent AOM (and by extrapolation ABRS) is 15% (0.6 × 0.5 × 0.5 = 0.15).

In contrast, let us assume that recently untreated ABRS has the same microbiology as recently untreated AOM. Then 45% would be due to ntHi, and 15% of those produce beta-lactamase. Again 50% of all the ntHi spontaneously clear without antibiotics. The expected clinical failure rate for amoxicillin would be 3%-4% due to beta-lactamase–producing ntHi (0.45 × 0.15 × 0.50 = 0.034). This relatively low rate of expected amoxicillin failure for a noninvasive AOM or ABRS pathogen does not seem to mandate addition of clavulanate.

Further, the higher resistance based on beta-lactamase production in ntHi that was quoted in the ABRS 2012 IDSA guidelines were from isolates of children who had tympanocentesis mostly for persistent or recurrent AOM. So, my deduction is that it is logical to use the beta-lactamase–stable drug combination as second-line therapy, that is, in persistent or recurrent AOM and by extrapolation, also in persistent or recurrent ABRS, but not as first-line therapy.

I also am concerned about using a lower dose of amoxicillin because this regimen would be expected to cover less than half of pneumococci with intermediate resistance to penicillin and none with high levels of penicillin resistance. Because pneumococcus is the potentially invasive and yet still common oto- and sinus pathogen, it seems logical to optimize coverage for pneumococcus rather than ntHi in as many young children as possible, particularly those not yet fully PCV13 immunized. This means high-dose amoxicillin, not standard-dose amoxicillin.

This high-dose amoxicillin is what is recommended in the 2013 AAP AOM guidelines. So I feel comfortable, based on the available AOM data, using high-dose amoxicillin (90 mg/kg per day divided in two daily doses) as empiric first-line therapy for non–penicillin-allergic ABRS patients. I would, however, use high-dose amoxicillin-clavulanate as second-line therapy for recurrent or persistent ABRS.

Summary

Most of us wish to follow rules and recommendations from groups of experts who laboriously review the literature and work many hours crafting them. However, sometimes we must remember that such rules are, as was stated in "Pirates of the Caribbean" in regard to "parlay," still only guidelines. When guidelines conflict and practicing clinicians are caught in the middle, we must consider the data and reasons underpinning the conflicting recommendations. Given the AAP AOM 2013 guidelines and examination of the available data, I am comfortable and feel that I am doing my part for antibiotic stewardship by using the same first- and second-line drugs for ABRS as recommended for AOM in the 2013 AOM guidelines.

Dr. Harrison is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Dr. Harrison said he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) has been suggested as a parallel pyogenic infection to acute otitis media (AOM). Like AOM, ABRS is due to obstruction of the normal drainage system into the nasopharynx from a normally aerated pouch(es) within the bone of the skull. Potential pathogens from the nasopharynx, having refluxed into the aerated spaces, begin to replicate and induce inflammation, at least in part due to the obstruction and the inflammation-induced deficiency of the normal cleansing system. For the middle ear, this system is the eustachian tube complex. For the sinuses, it is the osteomeatal complex. The similarities have led some to designate ABRS as "AOM in the middle of the face."

Other parallels are striking, including the microbiology, although 21st century data are less available for the microbiology of ABRS compared with AOM. The table lists some comparisons between the 2013 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines on managing AOM (Pediatrics 2013;131;e964-e999) and the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) ABRS guidelines (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:e72-e112).

So the question arises: Why was high-dose amoxicillin reaffirmed as the drug of choice for uncomplicated AOM in normal hosts in the 2013 AAP AOM guidelines, whereas the most recent guidelines for ABRS (2012 from IDSA) recommend standard-dose amoxicillin plus clavulanate? Amoxicillin is an inexpensive and reasonably palatable drug with a low adverse effect (AE) profile. Amoxicillin-clavulanate is a broader-spectrum, more expensive, somewhat bitter-tasting drug with a moderate AE profile. When the extra spectrum is needed, the added expense and AEs are acceptable. But they seem excessive for a first-line drug.

Do differences in diagnostic criteria lessen the impact on antimicrobial resistance from use of a broader-spectrum first-line drug for ABRS compared to AOM?

Compared with the 2013 AAP otitis media guidelines, which provide objective, clear, and simple criteria, the 2012 IDSA ABRS Guidelines have less objective and less precise criteria. For an AOM diagnosis, the tympanic membrane (TM) must be bulging or be perforated with purulent drainage. Both result from an expanding inflammatory process that stretches the TM. Using this single criterion in the presence of an effusion, clinicians have a clear understanding of what constitutes AOM. No more need to rely on history of acute onset, or a particular color or opacity, or lack of mobility on pneumatic otoscopy. One need only see a bulging TM and note that there is an inflammatory effusion. Bingo – this is AOM.

So, diagnosis of AOM is easier and can be more precise, eliminating "uncertain AOM" from the options. With these firm diagnostic criteria, the question then is whether the AOM episode requires antibiotics. That question is also addressed in the 2013 guidelines and will not be discussed here. The end result is that the 2013 AOM guidelines should decrease the number of AOM diagnoses and thereby antibiotic overuse.

Based on the 2012 IDSA Guideline for ABRS, in contrast, there are three sets of circumstances whereby an ABRS diagnosis can be made. For the most part these involve historical data about duration and intensity of symptoms reported by patients or parents. Thus these are varied, mostly subjective, and more complex with multiple nuances. There is more art and no real reliance on objective physical findings in diagnosing ABRS. This is due to there being no reliable physical findings to diagnose uncomplicated ABRS. There also is no reliable, inexpensive, and safe laboratory or radiological modality for ABRS diagnosis. This results in considerable wiggle room and subjective clinical judgment about the diagnosis.

And the 2012 IDSA ABRS guidelines state that antibiotic treatment should begin whenever an ABRS diagnosis is made. There is some verbiage that one could consider observation without antibiotics if the symptoms are mild, but there are no specifics about what constitutes "mild." This seems like the perfect storm for potential overdiagnosis and overuse of antibiotics, so a broader-spectrum drug would be less desirable from an antibiotic stewardship perspective.

Are pathogens in routine uncomplicated ABRS more resistant to amoxicillin than in AOM so that addition of clavulanate to neutralize beta-lactamase is warranted?

The 2012 ABRS guidelines indicate that the basis for recommending amoxicillin-clavulanate was the microbiology of AOM. There has been little pediatric ABRS microbiology in the past 25 years because sinus punctures are needed to have the best data. Such punctures have not been used in controlled trials in decades. So it is logical to use AOM data, given that pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) have produced shifts in pneumococcal serotypes, and there continues to be an evolving distribution of serotypes and their accompanying antibiotic resistance patterns since the 2010 shift to PCV13.

The current expectation is that serotype 19A, the most frequently multidrug-resistant serotype that emerged after PCV7 was introduced in 2000, will decline by the end of 2013. Other classic pneumococcal otopathogen serotypes expressing resistance to amoxicillin have declined since 2004, as has the overall prevalence of AOM due to pneumococcus. Since 2004, more than 50% of recently antibiotic-treated or recurrent AOM appear to be due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (ntHi), and more than half of these produce beta-lactamase. (Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004;23:829-33; Pediatr. Infect Dis. J. 2010;29:304-9). So more than 25% of recently antibiotic-treated AOM patients would be expected to have amoxicillin-resistant pathogens by virtue of beta-lactamase.

Is this a reasonable rationale for the first-line therapy for both AOM and ABRS to be standard (some would call low) dose, but beta-lactamase stable, amoxicillin-clavulanate at 45 mg/kg per day divided twice daily? This is the argument utilized in the 2012 IDSA ABRS guidelines. However, based on the same data, the AAP 2013 AOM guidelines conclude that high-dose amoxicillin without clavulanate should be used for first-line empiric therapy of AOM.

A powerful argument for the AAP AOM guidelines is the expectation that half of all ntHi, including those that produce beta-lactamase, will spontaneously clear without antibiotics. This is more frequent than for pneumococcus, which has only a 20% spontaneous remission. Data from our laboratory in Kansas City showed that up to 50% of the ntHi in persistent or recurrent AOM produce beta-lactamase; however, less than 15% do so in AOM when not recently treated with antibiotics (Harrison, C.J. The Changing Microbiology of Acute Otitis Media, in "Acute Otitis Media: Translating Science into Clinical Practice," International Congress and Symposium Series. 265:22-35. Royal Society of Medicine Press, London, 2007). How powerful then is the argument to add clavulanate and to use low-dose amoxicillin?

ntHi considered

First consider the contribution to amoxicillin failures by ntHi. Choosing a worst-case scenario of all ABRS having the microbiology of recently treated AOM, we will assume that 60% of persistent/recurrent AOM (and by extrapolation ABRS) is due to ntHi, and 50% of these produce beta-lactamase. Now factor in that 50% of all ntHi clear without antibiotics. The overall expected clinical failure rate for amoxicillin due to beta-lactamase producing ntHi in recurrent/persistent AOM (and by extrapolation ABRS) is 15% (0.6 × 0.5 × 0.5 = 0.15).

In contrast, let us assume that recently untreated ABRS has the same microbiology as recently untreated AOM. Then 45% would be due to ntHi, and 15% of those produce beta-lactamase. Again 50% of all the ntHi spontaneously clear without antibiotics. The expected clinical failure rate for amoxicillin would be 3%-4% due to beta-lactamase–producing ntHi (0.45 × 0.15 × 0.50 = 0.034). This relatively low rate of expected amoxicillin failure for a noninvasive AOM or ABRS pathogen does not seem to mandate addition of clavulanate.

Further, the higher resistance based on beta-lactamase production in ntHi that was quoted in the ABRS 2012 IDSA guidelines were from isolates of children who had tympanocentesis mostly for persistent or recurrent AOM. So, my deduction is that it is logical to use the beta-lactamase–stable drug combination as second-line therapy, that is, in persistent or recurrent AOM and by extrapolation, also in persistent or recurrent ABRS, but not as first-line therapy.

I also am concerned about using a lower dose of amoxicillin because this regimen would be expected to cover less than half of pneumococci with intermediate resistance to penicillin and none with high levels of penicillin resistance. Because pneumococcus is the potentially invasive and yet still common oto- and sinus pathogen, it seems logical to optimize coverage for pneumococcus rather than ntHi in as many young children as possible, particularly those not yet fully PCV13 immunized. This means high-dose amoxicillin, not standard-dose amoxicillin.

This high-dose amoxicillin is what is recommended in the 2013 AAP AOM guidelines. So I feel comfortable, based on the available AOM data, using high-dose amoxicillin (90 mg/kg per day divided in two daily doses) as empiric first-line therapy for non–penicillin-allergic ABRS patients. I would, however, use high-dose amoxicillin-clavulanate as second-line therapy for recurrent or persistent ABRS.

Summary

Most of us wish to follow rules and recommendations from groups of experts who laboriously review the literature and work many hours crafting them. However, sometimes we must remember that such rules are, as was stated in "Pirates of the Caribbean" in regard to "parlay," still only guidelines. When guidelines conflict and practicing clinicians are caught in the middle, we must consider the data and reasons underpinning the conflicting recommendations. Given the AAP AOM 2013 guidelines and examination of the available data, I am comfortable and feel that I am doing my part for antibiotic stewardship by using the same first- and second-line drugs for ABRS as recommended for AOM in the 2013 AOM guidelines.

Dr. Harrison is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Dr. Harrison said he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) has been suggested as a parallel pyogenic infection to acute otitis media (AOM). Like AOM, ABRS is due to obstruction of the normal drainage system into the nasopharynx from a normally aerated pouch(es) within the bone of the skull. Potential pathogens from the nasopharynx, having refluxed into the aerated spaces, begin to replicate and induce inflammation, at least in part due to the obstruction and the inflammation-induced deficiency of the normal cleansing system. For the middle ear, this system is the eustachian tube complex. For the sinuses, it is the osteomeatal complex. The similarities have led some to designate ABRS as "AOM in the middle of the face."

Other parallels are striking, including the microbiology, although 21st century data are less available for the microbiology of ABRS compared with AOM. The table lists some comparisons between the 2013 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines on managing AOM (Pediatrics 2013;131;e964-e999) and the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) ABRS guidelines (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:e72-e112).

So the question arises: Why was high-dose amoxicillin reaffirmed as the drug of choice for uncomplicated AOM in normal hosts in the 2013 AAP AOM guidelines, whereas the most recent guidelines for ABRS (2012 from IDSA) recommend standard-dose amoxicillin plus clavulanate? Amoxicillin is an inexpensive and reasonably palatable drug with a low adverse effect (AE) profile. Amoxicillin-clavulanate is a broader-spectrum, more expensive, somewhat bitter-tasting drug with a moderate AE profile. When the extra spectrum is needed, the added expense and AEs are acceptable. But they seem excessive for a first-line drug.

Do differences in diagnostic criteria lessen the impact on antimicrobial resistance from use of a broader-spectrum first-line drug for ABRS compared to AOM?

Compared with the 2013 AAP otitis media guidelines, which provide objective, clear, and simple criteria, the 2012 IDSA ABRS Guidelines have less objective and less precise criteria. For an AOM diagnosis, the tympanic membrane (TM) must be bulging or be perforated with purulent drainage. Both result from an expanding inflammatory process that stretches the TM. Using this single criterion in the presence of an effusion, clinicians have a clear understanding of what constitutes AOM. No more need to rely on history of acute onset, or a particular color or opacity, or lack of mobility on pneumatic otoscopy. One need only see a bulging TM and note that there is an inflammatory effusion. Bingo – this is AOM.

So, diagnosis of AOM is easier and can be more precise, eliminating "uncertain AOM" from the options. With these firm diagnostic criteria, the question then is whether the AOM episode requires antibiotics. That question is also addressed in the 2013 guidelines and will not be discussed here. The end result is that the 2013 AOM guidelines should decrease the number of AOM diagnoses and thereby antibiotic overuse.

Based on the 2012 IDSA Guideline for ABRS, in contrast, there are three sets of circumstances whereby an ABRS diagnosis can be made. For the most part these involve historical data about duration and intensity of symptoms reported by patients or parents. Thus these are varied, mostly subjective, and more complex with multiple nuances. There is more art and no real reliance on objective physical findings in diagnosing ABRS. This is due to there being no reliable physical findings to diagnose uncomplicated ABRS. There also is no reliable, inexpensive, and safe laboratory or radiological modality for ABRS diagnosis. This results in considerable wiggle room and subjective clinical judgment about the diagnosis.

And the 2012 IDSA ABRS guidelines state that antibiotic treatment should begin whenever an ABRS diagnosis is made. There is some verbiage that one could consider observation without antibiotics if the symptoms are mild, but there are no specifics about what constitutes "mild." This seems like the perfect storm for potential overdiagnosis and overuse of antibiotics, so a broader-spectrum drug would be less desirable from an antibiotic stewardship perspective.

Are pathogens in routine uncomplicated ABRS more resistant to amoxicillin than in AOM so that addition of clavulanate to neutralize beta-lactamase is warranted?

The 2012 ABRS guidelines indicate that the basis for recommending amoxicillin-clavulanate was the microbiology of AOM. There has been little pediatric ABRS microbiology in the past 25 years because sinus punctures are needed to have the best data. Such punctures have not been used in controlled trials in decades. So it is logical to use AOM data, given that pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) have produced shifts in pneumococcal serotypes, and there continues to be an evolving distribution of serotypes and their accompanying antibiotic resistance patterns since the 2010 shift to PCV13.

The current expectation is that serotype 19A, the most frequently multidrug-resistant serotype that emerged after PCV7 was introduced in 2000, will decline by the end of 2013. Other classic pneumococcal otopathogen serotypes expressing resistance to amoxicillin have declined since 2004, as has the overall prevalence of AOM due to pneumococcus. Since 2004, more than 50% of recently antibiotic-treated or recurrent AOM appear to be due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (ntHi), and more than half of these produce beta-lactamase. (Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004;23:829-33; Pediatr. Infect Dis. J. 2010;29:304-9). So more than 25% of recently antibiotic-treated AOM patients would be expected to have amoxicillin-resistant pathogens by virtue of beta-lactamase.

Is this a reasonable rationale for the first-line therapy for both AOM and ABRS to be standard (some would call low) dose, but beta-lactamase stable, amoxicillin-clavulanate at 45 mg/kg per day divided twice daily? This is the argument utilized in the 2012 IDSA ABRS guidelines. However, based on the same data, the AAP 2013 AOM guidelines conclude that high-dose amoxicillin without clavulanate should be used for first-line empiric therapy of AOM.

A powerful argument for the AAP AOM guidelines is the expectation that half of all ntHi, including those that produce beta-lactamase, will spontaneously clear without antibiotics. This is more frequent than for pneumococcus, which has only a 20% spontaneous remission. Data from our laboratory in Kansas City showed that up to 50% of the ntHi in persistent or recurrent AOM produce beta-lactamase; however, less than 15% do so in AOM when not recently treated with antibiotics (Harrison, C.J. The Changing Microbiology of Acute Otitis Media, in "Acute Otitis Media: Translating Science into Clinical Practice," International Congress and Symposium Series. 265:22-35. Royal Society of Medicine Press, London, 2007). How powerful then is the argument to add clavulanate and to use low-dose amoxicillin?

ntHi considered

First consider the contribution to amoxicillin failures by ntHi. Choosing a worst-case scenario of all ABRS having the microbiology of recently treated AOM, we will assume that 60% of persistent/recurrent AOM (and by extrapolation ABRS) is due to ntHi, and 50% of these produce beta-lactamase. Now factor in that 50% of all ntHi clear without antibiotics. The overall expected clinical failure rate for amoxicillin due to beta-lactamase producing ntHi in recurrent/persistent AOM (and by extrapolation ABRS) is 15% (0.6 × 0.5 × 0.5 = 0.15).

In contrast, let us assume that recently untreated ABRS has the same microbiology as recently untreated AOM. Then 45% would be due to ntHi, and 15% of those produce beta-lactamase. Again 50% of all the ntHi spontaneously clear without antibiotics. The expected clinical failure rate for amoxicillin would be 3%-4% due to beta-lactamase–producing ntHi (0.45 × 0.15 × 0.50 = 0.034). This relatively low rate of expected amoxicillin failure for a noninvasive AOM or ABRS pathogen does not seem to mandate addition of clavulanate.

Further, the higher resistance based on beta-lactamase production in ntHi that was quoted in the ABRS 2012 IDSA guidelines were from isolates of children who had tympanocentesis mostly for persistent or recurrent AOM. So, my deduction is that it is logical to use the beta-lactamase–stable drug combination as second-line therapy, that is, in persistent or recurrent AOM and by extrapolation, also in persistent or recurrent ABRS, but not as first-line therapy.

I also am concerned about using a lower dose of amoxicillin because this regimen would be expected to cover less than half of pneumococci with intermediate resistance to penicillin and none with high levels of penicillin resistance. Because pneumococcus is the potentially invasive and yet still common oto- and sinus pathogen, it seems logical to optimize coverage for pneumococcus rather than ntHi in as many young children as possible, particularly those not yet fully PCV13 immunized. This means high-dose amoxicillin, not standard-dose amoxicillin.

This high-dose amoxicillin is what is recommended in the 2013 AAP AOM guidelines. So I feel comfortable, based on the available AOM data, using high-dose amoxicillin (90 mg/kg per day divided in two daily doses) as empiric first-line therapy for non–penicillin-allergic ABRS patients. I would, however, use high-dose amoxicillin-clavulanate as second-line therapy for recurrent or persistent ABRS.

Summary

Most of us wish to follow rules and recommendations from groups of experts who laboriously review the literature and work many hours crafting them. However, sometimes we must remember that such rules are, as was stated in "Pirates of the Caribbean" in regard to "parlay," still only guidelines. When guidelines conflict and practicing clinicians are caught in the middle, we must consider the data and reasons underpinning the conflicting recommendations. Given the AAP AOM 2013 guidelines and examination of the available data, I am comfortable and feel that I am doing my part for antibiotic stewardship by using the same first- and second-line drugs for ABRS as recommended for AOM in the 2013 AOM guidelines.

Dr. Harrison is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Dr. Harrison said he has no relevant financial disclosures.