User login

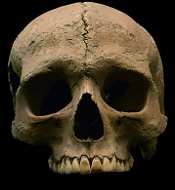

individual from Velia, Italy

Photo courtesy of Luca

Bandioli, Pigorini Museum

An analysis of 2000-year-old human remains from several regions across the Italian peninsula has confirmed the presence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria during the Roman Empire, according to researchers.

The team found mitochondrial genomic evidence of P falciparum malaria, coaxed from the teeth of bodies buried in 3 Italian cemeteries, dating back to the Imperial period.

The researchers said these finding provide a key reference point for when and where the malaria parasite existed in humans, as well as more information about the evolution of human disease.

The team reported these findings in Current Biology.

“There is extensive written evidence describing fevers that sound like malaria in ancient Greece and Rome, but the specific malaria species responsible is unknown,” said study author Stephanie Marciniak, PhD, of Pennsylvania State University in University Park.

“Our data confirm that the species was likely Plasmodium falciparum and that it affected people in different ecological and cultural environments. These results open up new questions to explore, particularly how widespread this parasite was and what burden it placed upon communities in Imperial Roman Italy.”

Dr Marciniak and her colleagues sampled teeth taken from 58 adults interred at 3 Imperial period Italian cemeteries: Isola Sacra, Velia, and Vagnari.

Located on the coast, Velia and Isola Sacra were known as important port cities and trading centers. Vagnari is located further inland and believed to be the burial site of laborers who would have worked on a Roman rural estate.

The researchers mined tiny DNA fragments from dental pulp. They were able to extract, purify, and enrich specifically for the Plasmodium species known to infect humans.

The team noted that usable DNA is challenging to extract because the parasites primarily dwell within the bloodstream and organs, which decompose and break down over time—in this instance, over the course of 2 millennia.

However, the researchers recovered more than half of the P falciparum mitochondrial genome from 2 individuals from Velia and Vagnari. ![]()

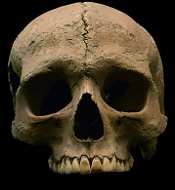

individual from Velia, Italy

Photo courtesy of Luca

Bandioli, Pigorini Museum

An analysis of 2000-year-old human remains from several regions across the Italian peninsula has confirmed the presence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria during the Roman Empire, according to researchers.

The team found mitochondrial genomic evidence of P falciparum malaria, coaxed from the teeth of bodies buried in 3 Italian cemeteries, dating back to the Imperial period.

The researchers said these finding provide a key reference point for when and where the malaria parasite existed in humans, as well as more information about the evolution of human disease.

The team reported these findings in Current Biology.

“There is extensive written evidence describing fevers that sound like malaria in ancient Greece and Rome, but the specific malaria species responsible is unknown,” said study author Stephanie Marciniak, PhD, of Pennsylvania State University in University Park.

“Our data confirm that the species was likely Plasmodium falciparum and that it affected people in different ecological and cultural environments. These results open up new questions to explore, particularly how widespread this parasite was and what burden it placed upon communities in Imperial Roman Italy.”

Dr Marciniak and her colleagues sampled teeth taken from 58 adults interred at 3 Imperial period Italian cemeteries: Isola Sacra, Velia, and Vagnari.

Located on the coast, Velia and Isola Sacra were known as important port cities and trading centers. Vagnari is located further inland and believed to be the burial site of laborers who would have worked on a Roman rural estate.

The researchers mined tiny DNA fragments from dental pulp. They were able to extract, purify, and enrich specifically for the Plasmodium species known to infect humans.

The team noted that usable DNA is challenging to extract because the parasites primarily dwell within the bloodstream and organs, which decompose and break down over time—in this instance, over the course of 2 millennia.

However, the researchers recovered more than half of the P falciparum mitochondrial genome from 2 individuals from Velia and Vagnari. ![]()

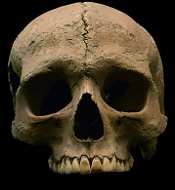

individual from Velia, Italy

Photo courtesy of Luca

Bandioli, Pigorini Museum

An analysis of 2000-year-old human remains from several regions across the Italian peninsula has confirmed the presence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria during the Roman Empire, according to researchers.

The team found mitochondrial genomic evidence of P falciparum malaria, coaxed from the teeth of bodies buried in 3 Italian cemeteries, dating back to the Imperial period.

The researchers said these finding provide a key reference point for when and where the malaria parasite existed in humans, as well as more information about the evolution of human disease.

The team reported these findings in Current Biology.

“There is extensive written evidence describing fevers that sound like malaria in ancient Greece and Rome, but the specific malaria species responsible is unknown,” said study author Stephanie Marciniak, PhD, of Pennsylvania State University in University Park.

“Our data confirm that the species was likely Plasmodium falciparum and that it affected people in different ecological and cultural environments. These results open up new questions to explore, particularly how widespread this parasite was and what burden it placed upon communities in Imperial Roman Italy.”

Dr Marciniak and her colleagues sampled teeth taken from 58 adults interred at 3 Imperial period Italian cemeteries: Isola Sacra, Velia, and Vagnari.

Located on the coast, Velia and Isola Sacra were known as important port cities and trading centers. Vagnari is located further inland and believed to be the burial site of laborers who would have worked on a Roman rural estate.

The researchers mined tiny DNA fragments from dental pulp. They were able to extract, purify, and enrich specifically for the Plasmodium species known to infect humans.

The team noted that usable DNA is challenging to extract because the parasites primarily dwell within the bloodstream and organs, which decompose and break down over time—in this instance, over the course of 2 millennia.

However, the researchers recovered more than half of the P falciparum mitochondrial genome from 2 individuals from Velia and Vagnari. ![]()