User login

Growth continues among palliative care programs in the United States, although access often depends “more upon accidents of geography than it does upon the needs of patients,” according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

“As is true for many aspects of health care, geography is destiny. Where you live determines your access to the best quality of life and highest quality of care during a serious illness,” said Diane E. Meier, MD, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in a written statement.

the two organizations said in their 2019 report card on palliative care access. What hasn’t changed since 2015, however, is the country’s overall grade, which remains a B.

Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have a palliative care program in all of their hospitals with 50 or more beds and each earned a grade of A (palliative care rate of greater than 80%), along with 17 other states. The lowest-performing states – Alabama, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – all received Ds for having a rate below 40%, the CAPC said.

The urban/rural divide also is prominent in palliative care: “90% of hospitals with palliative care are in urban areas. Only 17% of rural hospitals with fifty or more beds report palliative care programs,” the report said.

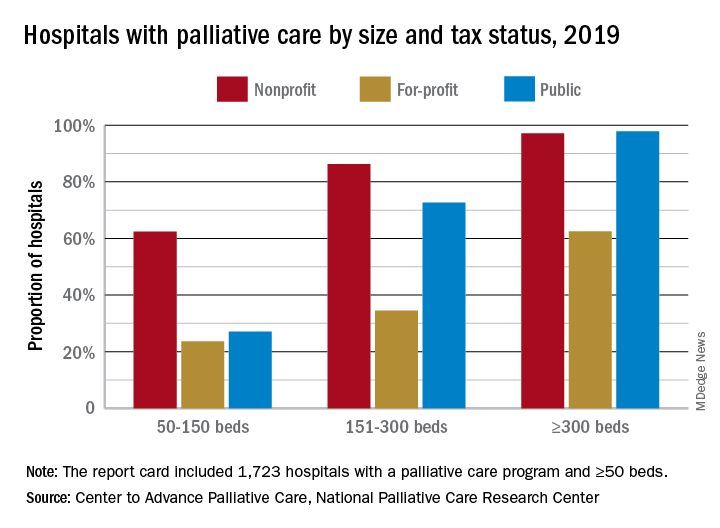

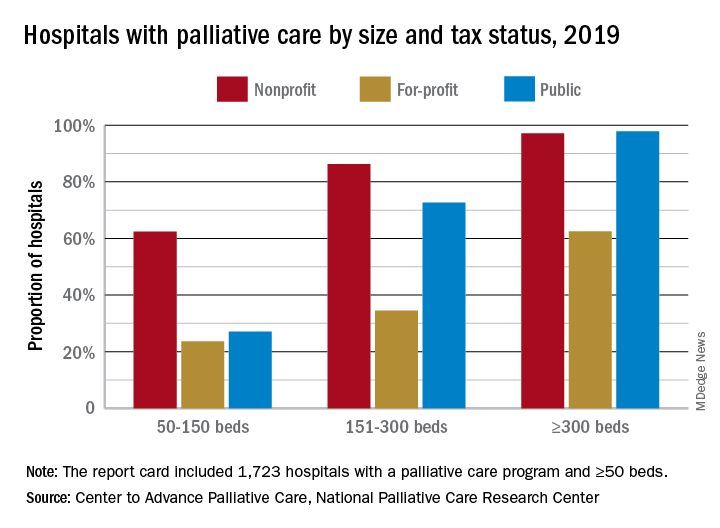

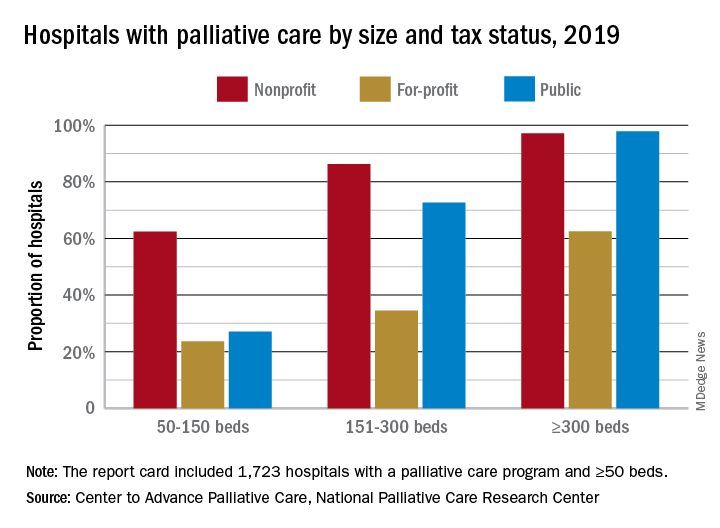

Hospital type is another source of disparity. Small, nonprofit hospitals are much more likely to offer access to palliative care than either for-profit or public facilities of the same size, but the gap closes as size increases, at least between nonprofit and public hospitals. For the largest institutions, the public hospitals pull into the lead, 98% versus 97%, over the nonprofits, with the for-profit facilities well behind at 63%.

“High quality palliative care has been shown to improve patient and family quality of life, improve patients’ and families’ health care experiences, and in certain diseases, prolong life. Palliative care has also been shown to improve hospital efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending,” said R. Sean Morrison, MD, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center.

The report card is based on data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey Database, with additional data from the National Palliative Care Registry and Center to Advance Palliative Care’s Mapping Community Palliative Care initiative. The final sample included 2,409 hospitals with 50 or more beds.

Growth continues among palliative care programs in the United States, although access often depends “more upon accidents of geography than it does upon the needs of patients,” according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

“As is true for many aspects of health care, geography is destiny. Where you live determines your access to the best quality of life and highest quality of care during a serious illness,” said Diane E. Meier, MD, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in a written statement.

the two organizations said in their 2019 report card on palliative care access. What hasn’t changed since 2015, however, is the country’s overall grade, which remains a B.

Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have a palliative care program in all of their hospitals with 50 or more beds and each earned a grade of A (palliative care rate of greater than 80%), along with 17 other states. The lowest-performing states – Alabama, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – all received Ds for having a rate below 40%, the CAPC said.

The urban/rural divide also is prominent in palliative care: “90% of hospitals with palliative care are in urban areas. Only 17% of rural hospitals with fifty or more beds report palliative care programs,” the report said.

Hospital type is another source of disparity. Small, nonprofit hospitals are much more likely to offer access to palliative care than either for-profit or public facilities of the same size, but the gap closes as size increases, at least between nonprofit and public hospitals. For the largest institutions, the public hospitals pull into the lead, 98% versus 97%, over the nonprofits, with the for-profit facilities well behind at 63%.

“High quality palliative care has been shown to improve patient and family quality of life, improve patients’ and families’ health care experiences, and in certain diseases, prolong life. Palliative care has also been shown to improve hospital efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending,” said R. Sean Morrison, MD, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center.

The report card is based on data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey Database, with additional data from the National Palliative Care Registry and Center to Advance Palliative Care’s Mapping Community Palliative Care initiative. The final sample included 2,409 hospitals with 50 or more beds.

Growth continues among palliative care programs in the United States, although access often depends “more upon accidents of geography than it does upon the needs of patients,” according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

“As is true for many aspects of health care, geography is destiny. Where you live determines your access to the best quality of life and highest quality of care during a serious illness,” said Diane E. Meier, MD, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in a written statement.

the two organizations said in their 2019 report card on palliative care access. What hasn’t changed since 2015, however, is the country’s overall grade, which remains a B.

Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have a palliative care program in all of their hospitals with 50 or more beds and each earned a grade of A (palliative care rate of greater than 80%), along with 17 other states. The lowest-performing states – Alabama, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – all received Ds for having a rate below 40%, the CAPC said.

The urban/rural divide also is prominent in palliative care: “90% of hospitals with palliative care are in urban areas. Only 17% of rural hospitals with fifty or more beds report palliative care programs,” the report said.

Hospital type is another source of disparity. Small, nonprofit hospitals are much more likely to offer access to palliative care than either for-profit or public facilities of the same size, but the gap closes as size increases, at least between nonprofit and public hospitals. For the largest institutions, the public hospitals pull into the lead, 98% versus 97%, over the nonprofits, with the for-profit facilities well behind at 63%.

“High quality palliative care has been shown to improve patient and family quality of life, improve patients’ and families’ health care experiences, and in certain diseases, prolong life. Palliative care has also been shown to improve hospital efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending,” said R. Sean Morrison, MD, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center.

The report card is based on data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey Database, with additional data from the National Palliative Care Registry and Center to Advance Palliative Care’s Mapping Community Palliative Care initiative. The final sample included 2,409 hospitals with 50 or more beds.