User login

Psychiatric patients stand to benefit greatly from adhering to prescribed pharmacotherapy, but many patients typically do not follow their medication regimens.1,2 Three months after pharmacotherapy is initiated, approximately 50% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) do not take their prescribed antidepressants.3 Adherence rates in patients with schizophrenia range from 50% to 60%, and patients with bipolar disorder have adherence rates as low as 35%.4-6 One possible explanation for “treatment-resistant” depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder may simply be nonadherence to prescribed pharmacotherapy.

Several strategies have been used to address this vexing problem (Table 1).7,8 They include individual and family psychoeducation,9,10 cognitive-behavioral therapy,11 interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, and family-focused therapy. This article describes an additional strategy I call “participatory pharmacotherapy.” In this model, the patient becomes a partner in the process of treatment choices and decision-making. This encourages patients to provide their own opinions and points of view regarding medication use. The prescribing clinician makes the patient feel that he or she has been listened to and understood. This and other techniques emphasize forming a therapeutic alliance with the patient before initiating pharmacotherapy. The patient provides information on his or her family history, medical and psychiatric history, and experience with previous medications, with a specific focus on which medications worked best for the patient and family members diagnosed with a similar condition.

Getting patients to participate

One of the fundamental tasks is to encourage patients to accept a participatory role, determine their underlying diagnosis, and co-create a treatment plan that will be most compatible with their illness and their personality. There are 10 components of establishing and practicing participatory pharmacotherapy.

1. Encourage patients to share their opinion of what a desirable treatment outcome should be. Some patients have unrealistic expectations about what medications can achieve. Clarify with patients what would be a realistic expectation of pharmacotherapy, and modify the patient’s beliefs to be compatible with a more probable outcome. For example, Ms. D, a 46-year-old mother of 2, is diagnosed with MDD, recurrent type without psychotic features. She states she expects pharmacotherapy will alleviate all symptoms and allow her to achieve a new healthy, happy state in which she will be able to laugh, socialize, and have fun every day for the rest of her life. Although achieving remission is a realistic and desirable treatment goal, Ms. D’s expectations are idealistic. Helping Ms. D accept and agree to realistic and achievable outcomes will improve her adherence to prescribed medications.

2. Encourage patients to share their ideas of how a desirable outcome can be accomplished. Similar to their expectations of outcomes, some patients have an unrealistic understanding of how treatment is conducted. Some patients expect treatment to be limited to prescribed medications or a one-time injection of a curative drug. Others prefer to use herbs and supplements and want to avoid prescribed medications. Understanding the patient’s expectations of how treatment is carried out will allow clinicians to provide patients with a rational view of treatment and establish a partnership based on realistic expectations.

3. Engage patients in choosing the best medication for them. Many patients have preconceived ideas about medications and which medicine would be best for them. They get this information from various sources, including family members and friends who benefitted from a specific drug, personal experience with medications, and exposure to drug advertising.

Understanding the patient’s preference for a specific medication and why he or she made such a choice is critical because doing so can take advantage of the patient’s self-fulfilling prophecies and improve the chances of obtaining a better outcome. For example, Mr. O, a 52-year-old father of 3, has been experiencing recurrent episodes of severe panic attacks. His clinician asked him to describe medications that in his opinion were most helpful in the past. He said he preferred clonazepam because it had helped him control the panic attacks and had minimal side effects, but he discontinued it after a previous psychotherapist told him he would become addicted to it. Obtaining this information was valuable because the clinician was able to clarify guidelines for clonazepam use without the risk of dependence. Mr. O is prescribed clonazepam, which he takes consistently and responds to excellently.

4. Involve patients in setting treatment goals and targeting symptoms to be relieved. Actively listen when patients describe their symptoms, discomforts, and past experiences with treatments. I invite patients to speak uninterrupted for 5 to 10 minutes, even if they talk about issues that seem irrelevant. I then summarize the patient’s major points and ask, “And what else?” After he or she says, “That’s it,” I ask the patient to assign a priority to alleviating each symptom.

For example, Ms. J, a 38-year-old married mother of 2, was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder. She listed her highest priority as controlling her impulsive shopping rather than alleviating depression, insomnia, or overeating. She had been forced to declare bankruptcy twice, and she was determined to never do so again. She also wanted to regain her husband’s trust and her ability to manage her finances. Ensuring that Ms. J felt understood regarding this issue increased the chances of establishing a solid treatment partnership. Providing Ms. J with a menu of treatment choices and asking her to describe her previous experiences with medications helped her and the clinician choose a medication that is compatible with her desire to control her impulsive shopping.

5. Engage patients in choosing the best delivery system for the prescribed medication. For many medications, clinicians can choose from a variety of delivery systems, including pills, transdermal patches, rectal or vaginal suppositories, creams, ointments, orally disintegrating tablets, liquids, and intramuscular injections. Patients have varying beliefs about the efficacy of particular delivery systems, based on personal experiences or what they have learned from the media, their family and friends, or the Internet. For example, Ms. S, age 28, experienced recurrent, disabling anxiety attacks. When asked about the best way of providing medication to relieve her symptoms, she chose gluteal injections because, as a child, her pediatrician had treated her for an unspecified illness by injecting medication in her buttock, which rapidly relieved her symptoms. This left her with the impression that injectable medications were the best therapeutic delivery system. After discussing the practicalities and availability of fast-acting medications to control panic attacks, we agreed to use orally disintegrating clonazepam, which is absorbed swiftly and provides fast symptom relief. Ms. S reported favorable results and was pleased with the process of developing this strategy with her clinician.

6. Involve patients in choosing the times and frequency of medication administration. The timing and frequency of medication administration can be used to enhance desirable therapeutic effects. For example, an antidepressant that causes sedation and somnolence could be taken at bedtime to help alleviate insomnia. Some studies have shown that taking a medication once a day improves adherence compared with taking the same medication in divided doses.13 Other patients may wish to take a medication several times a day so they can keep the medication in their purse or briefcase and feel confident that if they need a medication for immediate symptom relief, it will be readily available.

7. Teach patients to self-monitor changes and improvements in target symptoms. Engaging patients in a system of self-monitoring improves their chances of achieving successful treatment outcomes.14 Instruct patients to create a list of symptoms and monitor the intensity of each symptom using a rating scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represents the lowest intensity and 5 represents the highest. As for frequency, patients can rate each symptom from “not present” to “present most of the time.”

Self-monitoring allows patients to observe which daily behaviors and lifestyle choices make symptoms better and which make them worse. For example, Mrs. P, a 38-year-old married mother of 2, had anxiety and panic attacks associated with low self-esteem and chronic depression. Her clinician instructed her to use a 1-page form to monitor the frequency and intensity of her anxiety and panic symptoms by focusing on the physical manifestations, such as rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, nausea, tremors, dry mouth, frequent urination, and diarrhea to see if there was any correlation between her behaviors and her symptoms.

8. Instruct patients to call you to report any changes, including minor successes. Early in my career, toward the end of each appointment after I’d prescribed medications I’d tell patients, “Please call me if you have a problem.” Frequently, patients would call with a list of problems and side effects that they believed were caused by the newly prescribed medication. Later, I realized that I may have inadvertently encouraged patients to develop problems so they would have a reason to call me. To achieve a more favorable outcome I changed the way I communicate. I now say, “Please call me next week, even if you begin to feel better with this new medication.” The phone call is now associated with the idea that they will “get better,” and internalizing such a suggestion allows patients to talk with the clinician and report favorable treatment results.

9. Tell patients to monitor their successes by relabeling and reframing their symptoms. Mr. B, age 28, has MDD and reports irritability, insomnia, short temper, and restlessness. After reviewing his desired treatment outcome, we discuss the benefits of pharmacotherapy. I tell him the new medication will improve the quality and length of his sleep, which will allow his body and mind to recharge his “internal batteries” and restore health and energy. When we discuss side effects, I tell him to expect a dry mouth, which will be his signal that the medication is working. This discussion helps patients reframe side effects and improves their ability to tolerate side effects and adhere to pharmacotherapy.

10. Harness the placebo effect and the power of suggestion to increase chances of achieving the best treatment outcomes. In a previous article,12 I reviewed the principles of recognizing and enhancing the placebo effect and the power of suggestion to improve the chances of achieving better pharmacotherapy outcomes. When practicing participatory pharmacotherapy, clinicians are consciously aware of the power embedded in their words and are careful to use language that enhances the placebo effect and the power of suggestion when prescribing medications. Use the patient’s own language as a way of pacing yourself to the patient’s description of his or her distress. For example, Ms. R, a 42-year-old mother of 3, describes her experiences seeking help for her anxiety and depression, stating that she has not yet found the right combination of medications that provide benefits with tolerable side effects. Her clinician responds by focusing on the word “yet” (pacing) stating, “even though you have not yet found the right combination of medications to provide the most desirable benefit of beginning healing and restoring your hope, I promise to work with you and together we will try to achieve an improvement in your overall health and well-being.” This response includes several positive words and suggestions of future success, which are referred to as leading.

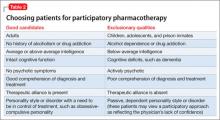

Not all patients will respond to participatory pharmacotherapy. Some factors will make patients good candidates for this approach, and others should be considered exclusionary qualities (Table 2).

Bottom Line

“Participatory pharmacotherapy” involves identifying patients as partners in the process of treatment choice and decision-making, encouraging them to provide their opinions regarding medication use, and making patients feel they have been heard and understood. This technique emphasizes forming a therapeutic alliance with the patient to improve patients’ adherence to pharmacotherapy and optimize treatment outcomes.

Related Resources

- Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(2);CD000011.

- Mahone IH. Shared decision making and serious mental illness. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2008;22(6):334-343.

- Russel CL, Ruppar TM, Metteson M. Improving medication adherence: moving from intention and motivation to a personal systems approach. Nurs Clin North Am. 2011;46(3):271-281.

- Tibaldi G, Salvador-Carulla L, Garcia-Gutierrez JC. From treatment adherence to advanced shared decision making: New professional strategies and attitudes in mental health care. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2011;6(2):91-99.

Drug Brand Name

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Disclosure

Dr. Torem reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, et al. Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1653-1664.

2. Nosé M, Barbui C, Gray R, et al. Clinical interventions for treatment non-adherence in psychosis: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:197-206.

3. Vergouwen AC, van Hout HP, Bakker A. Methods to improve patient compliance in the use of antidepressants. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2002;146:204-207.

4. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892-909.

5. Perkins DO. Predictors of noncompliance in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:1121-1128.

6. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment noncompliance in euthymic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:549-555.

7. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487-497.

8. Osterberg LG, Rudd R. Medication adherence for antihypertensive therapy. In: Oparil S, Weber MA, eds. Hypertension: a companion to Brenner and Rector’s the kidney. 2nd ed. Philadelphia. PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:848.

9. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16:306-324.

10. Miklowitz DJ. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008; 165:1408-1419.

11. Szentagotai A, David D. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:66-72.

12. Torem MS. Words to the wise: 4 secrets of successful pharmacotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(12):19-24.

13. Medic G, Higashi K, Littlewood KJ, et al. Dosing frequency and adherence in chronic psychiatric disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013; 9:119-131.

14. Virdi N, Daskiran M, Nigam S, et al. The association of self-monitoring of blood glucose use with medication adherence and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes initiating non-insulin treatment. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(9):790-798.

Psychiatric patients stand to benefit greatly from adhering to prescribed pharmacotherapy, but many patients typically do not follow their medication regimens.1,2 Three months after pharmacotherapy is initiated, approximately 50% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) do not take their prescribed antidepressants.3 Adherence rates in patients with schizophrenia range from 50% to 60%, and patients with bipolar disorder have adherence rates as low as 35%.4-6 One possible explanation for “treatment-resistant” depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder may simply be nonadherence to prescribed pharmacotherapy.

Several strategies have been used to address this vexing problem (Table 1).7,8 They include individual and family psychoeducation,9,10 cognitive-behavioral therapy,11 interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, and family-focused therapy. This article describes an additional strategy I call “participatory pharmacotherapy.” In this model, the patient becomes a partner in the process of treatment choices and decision-making. This encourages patients to provide their own opinions and points of view regarding medication use. The prescribing clinician makes the patient feel that he or she has been listened to and understood. This and other techniques emphasize forming a therapeutic alliance with the patient before initiating pharmacotherapy. The patient provides information on his or her family history, medical and psychiatric history, and experience with previous medications, with a specific focus on which medications worked best for the patient and family members diagnosed with a similar condition.

Getting patients to participate

One of the fundamental tasks is to encourage patients to accept a participatory role, determine their underlying diagnosis, and co-create a treatment plan that will be most compatible with their illness and their personality. There are 10 components of establishing and practicing participatory pharmacotherapy.

1. Encourage patients to share their opinion of what a desirable treatment outcome should be. Some patients have unrealistic expectations about what medications can achieve. Clarify with patients what would be a realistic expectation of pharmacotherapy, and modify the patient’s beliefs to be compatible with a more probable outcome. For example, Ms. D, a 46-year-old mother of 2, is diagnosed with MDD, recurrent type without psychotic features. She states she expects pharmacotherapy will alleviate all symptoms and allow her to achieve a new healthy, happy state in which she will be able to laugh, socialize, and have fun every day for the rest of her life. Although achieving remission is a realistic and desirable treatment goal, Ms. D’s expectations are idealistic. Helping Ms. D accept and agree to realistic and achievable outcomes will improve her adherence to prescribed medications.

2. Encourage patients to share their ideas of how a desirable outcome can be accomplished. Similar to their expectations of outcomes, some patients have an unrealistic understanding of how treatment is conducted. Some patients expect treatment to be limited to prescribed medications or a one-time injection of a curative drug. Others prefer to use herbs and supplements and want to avoid prescribed medications. Understanding the patient’s expectations of how treatment is carried out will allow clinicians to provide patients with a rational view of treatment and establish a partnership based on realistic expectations.

3. Engage patients in choosing the best medication for them. Many patients have preconceived ideas about medications and which medicine would be best for them. They get this information from various sources, including family members and friends who benefitted from a specific drug, personal experience with medications, and exposure to drug advertising.

Understanding the patient’s preference for a specific medication and why he or she made such a choice is critical because doing so can take advantage of the patient’s self-fulfilling prophecies and improve the chances of obtaining a better outcome. For example, Mr. O, a 52-year-old father of 3, has been experiencing recurrent episodes of severe panic attacks. His clinician asked him to describe medications that in his opinion were most helpful in the past. He said he preferred clonazepam because it had helped him control the panic attacks and had minimal side effects, but he discontinued it after a previous psychotherapist told him he would become addicted to it. Obtaining this information was valuable because the clinician was able to clarify guidelines for clonazepam use without the risk of dependence. Mr. O is prescribed clonazepam, which he takes consistently and responds to excellently.

4. Involve patients in setting treatment goals and targeting symptoms to be relieved. Actively listen when patients describe their symptoms, discomforts, and past experiences with treatments. I invite patients to speak uninterrupted for 5 to 10 minutes, even if they talk about issues that seem irrelevant. I then summarize the patient’s major points and ask, “And what else?” After he or she says, “That’s it,” I ask the patient to assign a priority to alleviating each symptom.

For example, Ms. J, a 38-year-old married mother of 2, was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder. She listed her highest priority as controlling her impulsive shopping rather than alleviating depression, insomnia, or overeating. She had been forced to declare bankruptcy twice, and she was determined to never do so again. She also wanted to regain her husband’s trust and her ability to manage her finances. Ensuring that Ms. J felt understood regarding this issue increased the chances of establishing a solid treatment partnership. Providing Ms. J with a menu of treatment choices and asking her to describe her previous experiences with medications helped her and the clinician choose a medication that is compatible with her desire to control her impulsive shopping.

5. Engage patients in choosing the best delivery system for the prescribed medication. For many medications, clinicians can choose from a variety of delivery systems, including pills, transdermal patches, rectal or vaginal suppositories, creams, ointments, orally disintegrating tablets, liquids, and intramuscular injections. Patients have varying beliefs about the efficacy of particular delivery systems, based on personal experiences or what they have learned from the media, their family and friends, or the Internet. For example, Ms. S, age 28, experienced recurrent, disabling anxiety attacks. When asked about the best way of providing medication to relieve her symptoms, she chose gluteal injections because, as a child, her pediatrician had treated her for an unspecified illness by injecting medication in her buttock, which rapidly relieved her symptoms. This left her with the impression that injectable medications were the best therapeutic delivery system. After discussing the practicalities and availability of fast-acting medications to control panic attacks, we agreed to use orally disintegrating clonazepam, which is absorbed swiftly and provides fast symptom relief. Ms. S reported favorable results and was pleased with the process of developing this strategy with her clinician.

6. Involve patients in choosing the times and frequency of medication administration. The timing and frequency of medication administration can be used to enhance desirable therapeutic effects. For example, an antidepressant that causes sedation and somnolence could be taken at bedtime to help alleviate insomnia. Some studies have shown that taking a medication once a day improves adherence compared with taking the same medication in divided doses.13 Other patients may wish to take a medication several times a day so they can keep the medication in their purse or briefcase and feel confident that if they need a medication for immediate symptom relief, it will be readily available.

7. Teach patients to self-monitor changes and improvements in target symptoms. Engaging patients in a system of self-monitoring improves their chances of achieving successful treatment outcomes.14 Instruct patients to create a list of symptoms and monitor the intensity of each symptom using a rating scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represents the lowest intensity and 5 represents the highest. As for frequency, patients can rate each symptom from “not present” to “present most of the time.”

Self-monitoring allows patients to observe which daily behaviors and lifestyle choices make symptoms better and which make them worse. For example, Mrs. P, a 38-year-old married mother of 2, had anxiety and panic attacks associated with low self-esteem and chronic depression. Her clinician instructed her to use a 1-page form to monitor the frequency and intensity of her anxiety and panic symptoms by focusing on the physical manifestations, such as rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, nausea, tremors, dry mouth, frequent urination, and diarrhea to see if there was any correlation between her behaviors and her symptoms.

8. Instruct patients to call you to report any changes, including minor successes. Early in my career, toward the end of each appointment after I’d prescribed medications I’d tell patients, “Please call me if you have a problem.” Frequently, patients would call with a list of problems and side effects that they believed were caused by the newly prescribed medication. Later, I realized that I may have inadvertently encouraged patients to develop problems so they would have a reason to call me. To achieve a more favorable outcome I changed the way I communicate. I now say, “Please call me next week, even if you begin to feel better with this new medication.” The phone call is now associated with the idea that they will “get better,” and internalizing such a suggestion allows patients to talk with the clinician and report favorable treatment results.

9. Tell patients to monitor their successes by relabeling and reframing their symptoms. Mr. B, age 28, has MDD and reports irritability, insomnia, short temper, and restlessness. After reviewing his desired treatment outcome, we discuss the benefits of pharmacotherapy. I tell him the new medication will improve the quality and length of his sleep, which will allow his body and mind to recharge his “internal batteries” and restore health and energy. When we discuss side effects, I tell him to expect a dry mouth, which will be his signal that the medication is working. This discussion helps patients reframe side effects and improves their ability to tolerate side effects and adhere to pharmacotherapy.

10. Harness the placebo effect and the power of suggestion to increase chances of achieving the best treatment outcomes. In a previous article,12 I reviewed the principles of recognizing and enhancing the placebo effect and the power of suggestion to improve the chances of achieving better pharmacotherapy outcomes. When practicing participatory pharmacotherapy, clinicians are consciously aware of the power embedded in their words and are careful to use language that enhances the placebo effect and the power of suggestion when prescribing medications. Use the patient’s own language as a way of pacing yourself to the patient’s description of his or her distress. For example, Ms. R, a 42-year-old mother of 3, describes her experiences seeking help for her anxiety and depression, stating that she has not yet found the right combination of medications that provide benefits with tolerable side effects. Her clinician responds by focusing on the word “yet” (pacing) stating, “even though you have not yet found the right combination of medications to provide the most desirable benefit of beginning healing and restoring your hope, I promise to work with you and together we will try to achieve an improvement in your overall health and well-being.” This response includes several positive words and suggestions of future success, which are referred to as leading.

Not all patients will respond to participatory pharmacotherapy. Some factors will make patients good candidates for this approach, and others should be considered exclusionary qualities (Table 2).

Bottom Line

“Participatory pharmacotherapy” involves identifying patients as partners in the process of treatment choice and decision-making, encouraging them to provide their opinions regarding medication use, and making patients feel they have been heard and understood. This technique emphasizes forming a therapeutic alliance with the patient to improve patients’ adherence to pharmacotherapy and optimize treatment outcomes.

Related Resources

- Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(2);CD000011.

- Mahone IH. Shared decision making and serious mental illness. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2008;22(6):334-343.

- Russel CL, Ruppar TM, Metteson M. Improving medication adherence: moving from intention and motivation to a personal systems approach. Nurs Clin North Am. 2011;46(3):271-281.

- Tibaldi G, Salvador-Carulla L, Garcia-Gutierrez JC. From treatment adherence to advanced shared decision making: New professional strategies and attitudes in mental health care. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2011;6(2):91-99.

Drug Brand Name

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Disclosure

Dr. Torem reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Psychiatric patients stand to benefit greatly from adhering to prescribed pharmacotherapy, but many patients typically do not follow their medication regimens.1,2 Three months after pharmacotherapy is initiated, approximately 50% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) do not take their prescribed antidepressants.3 Adherence rates in patients with schizophrenia range from 50% to 60%, and patients with bipolar disorder have adherence rates as low as 35%.4-6 One possible explanation for “treatment-resistant” depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder may simply be nonadherence to prescribed pharmacotherapy.

Several strategies have been used to address this vexing problem (Table 1).7,8 They include individual and family psychoeducation,9,10 cognitive-behavioral therapy,11 interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, and family-focused therapy. This article describes an additional strategy I call “participatory pharmacotherapy.” In this model, the patient becomes a partner in the process of treatment choices and decision-making. This encourages patients to provide their own opinions and points of view regarding medication use. The prescribing clinician makes the patient feel that he or she has been listened to and understood. This and other techniques emphasize forming a therapeutic alliance with the patient before initiating pharmacotherapy. The patient provides information on his or her family history, medical and psychiatric history, and experience with previous medications, with a specific focus on which medications worked best for the patient and family members diagnosed with a similar condition.

Getting patients to participate

One of the fundamental tasks is to encourage patients to accept a participatory role, determine their underlying diagnosis, and co-create a treatment plan that will be most compatible with their illness and their personality. There are 10 components of establishing and practicing participatory pharmacotherapy.

1. Encourage patients to share their opinion of what a desirable treatment outcome should be. Some patients have unrealistic expectations about what medications can achieve. Clarify with patients what would be a realistic expectation of pharmacotherapy, and modify the patient’s beliefs to be compatible with a more probable outcome. For example, Ms. D, a 46-year-old mother of 2, is diagnosed with MDD, recurrent type without psychotic features. She states she expects pharmacotherapy will alleviate all symptoms and allow her to achieve a new healthy, happy state in which she will be able to laugh, socialize, and have fun every day for the rest of her life. Although achieving remission is a realistic and desirable treatment goal, Ms. D’s expectations are idealistic. Helping Ms. D accept and agree to realistic and achievable outcomes will improve her adherence to prescribed medications.

2. Encourage patients to share their ideas of how a desirable outcome can be accomplished. Similar to their expectations of outcomes, some patients have an unrealistic understanding of how treatment is conducted. Some patients expect treatment to be limited to prescribed medications or a one-time injection of a curative drug. Others prefer to use herbs and supplements and want to avoid prescribed medications. Understanding the patient’s expectations of how treatment is carried out will allow clinicians to provide patients with a rational view of treatment and establish a partnership based on realistic expectations.

3. Engage patients in choosing the best medication for them. Many patients have preconceived ideas about medications and which medicine would be best for them. They get this information from various sources, including family members and friends who benefitted from a specific drug, personal experience with medications, and exposure to drug advertising.

Understanding the patient’s preference for a specific medication and why he or she made such a choice is critical because doing so can take advantage of the patient’s self-fulfilling prophecies and improve the chances of obtaining a better outcome. For example, Mr. O, a 52-year-old father of 3, has been experiencing recurrent episodes of severe panic attacks. His clinician asked him to describe medications that in his opinion were most helpful in the past. He said he preferred clonazepam because it had helped him control the panic attacks and had minimal side effects, but he discontinued it after a previous psychotherapist told him he would become addicted to it. Obtaining this information was valuable because the clinician was able to clarify guidelines for clonazepam use without the risk of dependence. Mr. O is prescribed clonazepam, which he takes consistently and responds to excellently.

4. Involve patients in setting treatment goals and targeting symptoms to be relieved. Actively listen when patients describe their symptoms, discomforts, and past experiences with treatments. I invite patients to speak uninterrupted for 5 to 10 minutes, even if they talk about issues that seem irrelevant. I then summarize the patient’s major points and ask, “And what else?” After he or she says, “That’s it,” I ask the patient to assign a priority to alleviating each symptom.

For example, Ms. J, a 38-year-old married mother of 2, was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder. She listed her highest priority as controlling her impulsive shopping rather than alleviating depression, insomnia, or overeating. She had been forced to declare bankruptcy twice, and she was determined to never do so again. She also wanted to regain her husband’s trust and her ability to manage her finances. Ensuring that Ms. J felt understood regarding this issue increased the chances of establishing a solid treatment partnership. Providing Ms. J with a menu of treatment choices and asking her to describe her previous experiences with medications helped her and the clinician choose a medication that is compatible with her desire to control her impulsive shopping.

5. Engage patients in choosing the best delivery system for the prescribed medication. For many medications, clinicians can choose from a variety of delivery systems, including pills, transdermal patches, rectal or vaginal suppositories, creams, ointments, orally disintegrating tablets, liquids, and intramuscular injections. Patients have varying beliefs about the efficacy of particular delivery systems, based on personal experiences or what they have learned from the media, their family and friends, or the Internet. For example, Ms. S, age 28, experienced recurrent, disabling anxiety attacks. When asked about the best way of providing medication to relieve her symptoms, she chose gluteal injections because, as a child, her pediatrician had treated her for an unspecified illness by injecting medication in her buttock, which rapidly relieved her symptoms. This left her with the impression that injectable medications were the best therapeutic delivery system. After discussing the practicalities and availability of fast-acting medications to control panic attacks, we agreed to use orally disintegrating clonazepam, which is absorbed swiftly and provides fast symptom relief. Ms. S reported favorable results and was pleased with the process of developing this strategy with her clinician.

6. Involve patients in choosing the times and frequency of medication administration. The timing and frequency of medication administration can be used to enhance desirable therapeutic effects. For example, an antidepressant that causes sedation and somnolence could be taken at bedtime to help alleviate insomnia. Some studies have shown that taking a medication once a day improves adherence compared with taking the same medication in divided doses.13 Other patients may wish to take a medication several times a day so they can keep the medication in their purse or briefcase and feel confident that if they need a medication for immediate symptom relief, it will be readily available.

7. Teach patients to self-monitor changes and improvements in target symptoms. Engaging patients in a system of self-monitoring improves their chances of achieving successful treatment outcomes.14 Instruct patients to create a list of symptoms and monitor the intensity of each symptom using a rating scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represents the lowest intensity and 5 represents the highest. As for frequency, patients can rate each symptom from “not present” to “present most of the time.”

Self-monitoring allows patients to observe which daily behaviors and lifestyle choices make symptoms better and which make them worse. For example, Mrs. P, a 38-year-old married mother of 2, had anxiety and panic attacks associated with low self-esteem and chronic depression. Her clinician instructed her to use a 1-page form to monitor the frequency and intensity of her anxiety and panic symptoms by focusing on the physical manifestations, such as rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, nausea, tremors, dry mouth, frequent urination, and diarrhea to see if there was any correlation between her behaviors and her symptoms.

8. Instruct patients to call you to report any changes, including minor successes. Early in my career, toward the end of each appointment after I’d prescribed medications I’d tell patients, “Please call me if you have a problem.” Frequently, patients would call with a list of problems and side effects that they believed were caused by the newly prescribed medication. Later, I realized that I may have inadvertently encouraged patients to develop problems so they would have a reason to call me. To achieve a more favorable outcome I changed the way I communicate. I now say, “Please call me next week, even if you begin to feel better with this new medication.” The phone call is now associated with the idea that they will “get better,” and internalizing such a suggestion allows patients to talk with the clinician and report favorable treatment results.

9. Tell patients to monitor their successes by relabeling and reframing their symptoms. Mr. B, age 28, has MDD and reports irritability, insomnia, short temper, and restlessness. After reviewing his desired treatment outcome, we discuss the benefits of pharmacotherapy. I tell him the new medication will improve the quality and length of his sleep, which will allow his body and mind to recharge his “internal batteries” and restore health and energy. When we discuss side effects, I tell him to expect a dry mouth, which will be his signal that the medication is working. This discussion helps patients reframe side effects and improves their ability to tolerate side effects and adhere to pharmacotherapy.

10. Harness the placebo effect and the power of suggestion to increase chances of achieving the best treatment outcomes. In a previous article,12 I reviewed the principles of recognizing and enhancing the placebo effect and the power of suggestion to improve the chances of achieving better pharmacotherapy outcomes. When practicing participatory pharmacotherapy, clinicians are consciously aware of the power embedded in their words and are careful to use language that enhances the placebo effect and the power of suggestion when prescribing medications. Use the patient’s own language as a way of pacing yourself to the patient’s description of his or her distress. For example, Ms. R, a 42-year-old mother of 3, describes her experiences seeking help for her anxiety and depression, stating that she has not yet found the right combination of medications that provide benefits with tolerable side effects. Her clinician responds by focusing on the word “yet” (pacing) stating, “even though you have not yet found the right combination of medications to provide the most desirable benefit of beginning healing and restoring your hope, I promise to work with you and together we will try to achieve an improvement in your overall health and well-being.” This response includes several positive words and suggestions of future success, which are referred to as leading.

Not all patients will respond to participatory pharmacotherapy. Some factors will make patients good candidates for this approach, and others should be considered exclusionary qualities (Table 2).

Bottom Line

“Participatory pharmacotherapy” involves identifying patients as partners in the process of treatment choice and decision-making, encouraging them to provide their opinions regarding medication use, and making patients feel they have been heard and understood. This technique emphasizes forming a therapeutic alliance with the patient to improve patients’ adherence to pharmacotherapy and optimize treatment outcomes.

Related Resources

- Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(2);CD000011.

- Mahone IH. Shared decision making and serious mental illness. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2008;22(6):334-343.

- Russel CL, Ruppar TM, Metteson M. Improving medication adherence: moving from intention and motivation to a personal systems approach. Nurs Clin North Am. 2011;46(3):271-281.

- Tibaldi G, Salvador-Carulla L, Garcia-Gutierrez JC. From treatment adherence to advanced shared decision making: New professional strategies and attitudes in mental health care. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2011;6(2):91-99.

Drug Brand Name

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Disclosure

Dr. Torem reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, et al. Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1653-1664.

2. Nosé M, Barbui C, Gray R, et al. Clinical interventions for treatment non-adherence in psychosis: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:197-206.

3. Vergouwen AC, van Hout HP, Bakker A. Methods to improve patient compliance in the use of antidepressants. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2002;146:204-207.

4. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892-909.

5. Perkins DO. Predictors of noncompliance in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:1121-1128.

6. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment noncompliance in euthymic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:549-555.

7. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487-497.

8. Osterberg LG, Rudd R. Medication adherence for antihypertensive therapy. In: Oparil S, Weber MA, eds. Hypertension: a companion to Brenner and Rector’s the kidney. 2nd ed. Philadelphia. PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:848.

9. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16:306-324.

10. Miklowitz DJ. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008; 165:1408-1419.

11. Szentagotai A, David D. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:66-72.

12. Torem MS. Words to the wise: 4 secrets of successful pharmacotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(12):19-24.

13. Medic G, Higashi K, Littlewood KJ, et al. Dosing frequency and adherence in chronic psychiatric disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013; 9:119-131.

14. Virdi N, Daskiran M, Nigam S, et al. The association of self-monitoring of blood glucose use with medication adherence and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes initiating non-insulin treatment. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(9):790-798.

1. Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, et al. Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1653-1664.

2. Nosé M, Barbui C, Gray R, et al. Clinical interventions for treatment non-adherence in psychosis: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:197-206.

3. Vergouwen AC, van Hout HP, Bakker A. Methods to improve patient compliance in the use of antidepressants. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2002;146:204-207.

4. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892-909.

5. Perkins DO. Predictors of noncompliance in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:1121-1128.

6. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment noncompliance in euthymic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:549-555.

7. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487-497.

8. Osterberg LG, Rudd R. Medication adherence for antihypertensive therapy. In: Oparil S, Weber MA, eds. Hypertension: a companion to Brenner and Rector’s the kidney. 2nd ed. Philadelphia. PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:848.

9. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16:306-324.

10. Miklowitz DJ. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008; 165:1408-1419.

11. Szentagotai A, David D. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:66-72.

12. Torem MS. Words to the wise: 4 secrets of successful pharmacotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(12):19-24.

13. Medic G, Higashi K, Littlewood KJ, et al. Dosing frequency and adherence in chronic psychiatric disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013; 9:119-131.

14. Virdi N, Daskiran M, Nigam S, et al. The association of self-monitoring of blood glucose use with medication adherence and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes initiating non-insulin treatment. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(9):790-798.