User login

As part of the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News, it is intriguing to think about where a time machine journey 5 decades back would find the field of pediatric dermatology, and to assess the changes in the specialty during the time that Dermatology News (operating then as “Skin & Allergy News”) has been reporting on innovations and changes in the practice of dermatology.

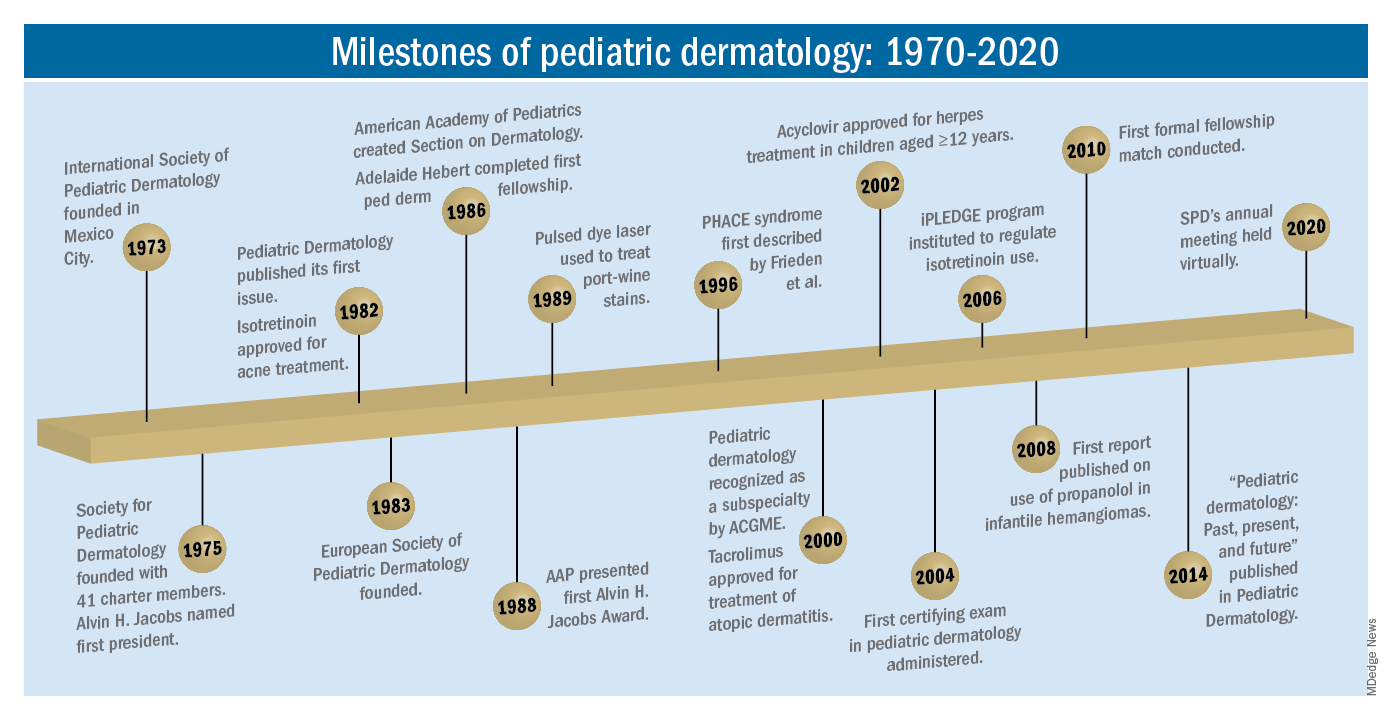

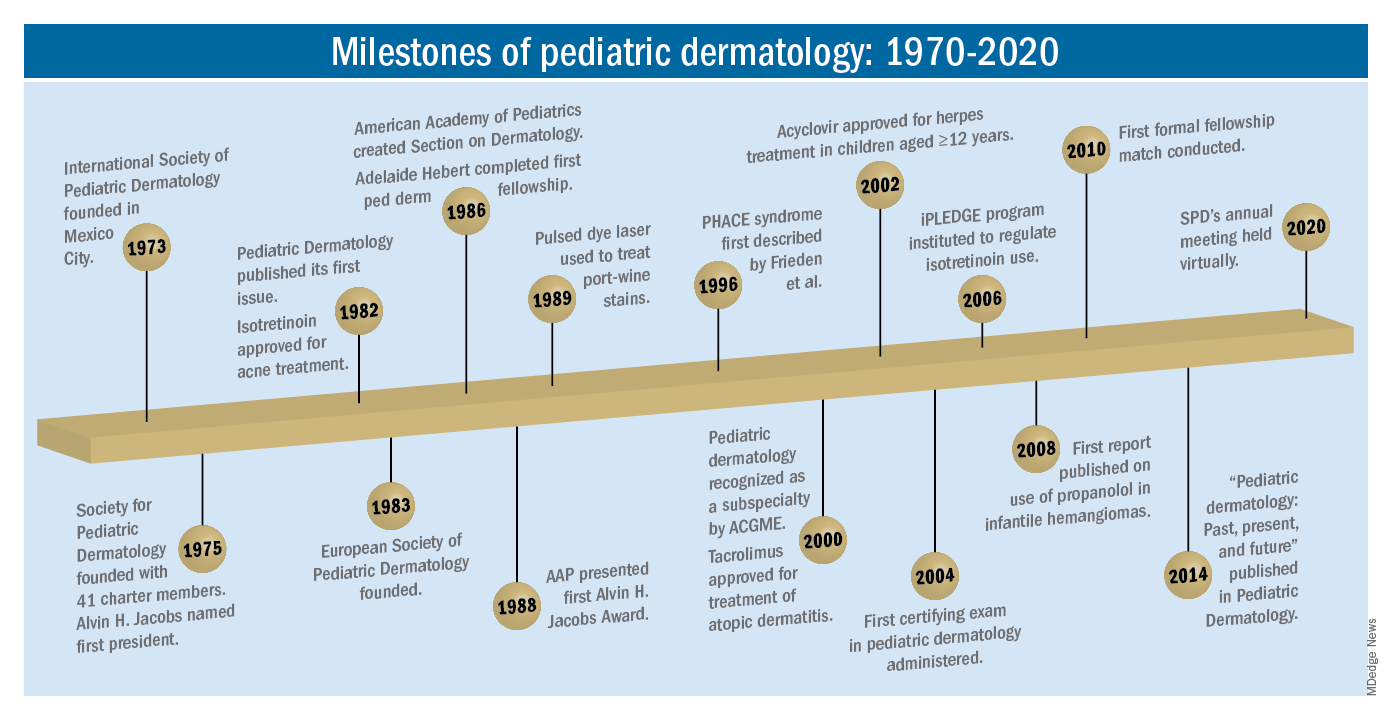

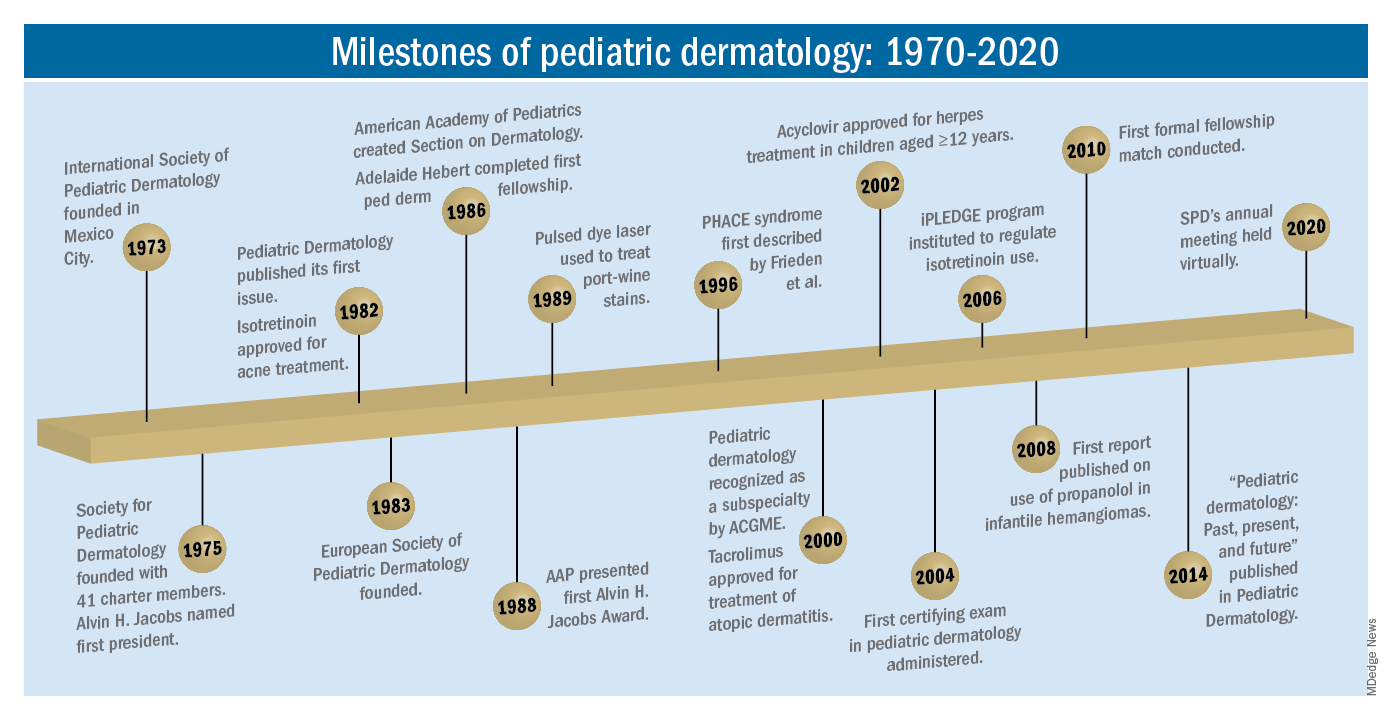

So, starting . It was not until 3 years later, in October 1973 in Mexico City, that the first international symposium on Pediatric Dermatology was held, and the International Society for Pediatric Dermatology was founded. I reached out to Andrew Margileth, MD, 100 years old this past July, and still active voluntary faculty in pediatric dermatology at the University of Miami, to help me “reach back” to those days. Dr. Margileth commented on how the first symposium was “brilliantly orchestrated by Ramon Ruiz-Maldonado,” from the National Institute of Paediatrics in Mexico, and that it was his “Aha moment for future practice!” That meeting spurred discussions on the development of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology the next year, with Alvin Jacobs, MD; Samuel Weinberg, MD; Nancy Esterly, MD; Sidney Hurwitz, MD; William Weston, MD; and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers,” and the society was officially established in 1975.

The field of pediatric dermatology was fairly “infantile” 50 years ago, with few practitioners. But the early leaders in the field recognized that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits included skin problems, and that there was limited training for dermatologists, as well as pediatricians, about skin diseases in children. There were clearly clinical and educational needs to establish a subspecialty of pediatric dermatology, and over the next 1-2 decades, the field expanded. The journal Pediatric Dermatology was established (in 1982), the Section on Dermatology was established by the American Academy of Pediatrics (in 1986), and fellowship programs were launched at select academic centers. And it was 30 years into our timeline before the formal subspecialty of pediatric dermatology was established through the American Board of Dermatology (2000).

The field of pediatric dermatology has evolved and matured rapidly. Standard reference textbooks have been developed in the United States and around the world (and of course, online). Pediatric dermatology is an essential part of the core curriculum for dermatologist trainees. Organizations promoting pediatric research have developed to influence basic, translational, and clinical research in conditions in neonates through adolescents, such as the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA). And meetings throughout the world now feature pediatric dermatology sessions and help to spread the advances in the diagnosis and management of pediatric skin disorders.

The practice of pediatric dermatology: How has it changed?

It is beyond the scope of this article to try to comprehensively review all of the changes in pediatric dermatology practice. But review of the evolution of a few disease states (choices influenced by my discussions with my 100-year old history guide, Dr. Margileth) displays examples of where we have been, and where we are going in our next 5, 10, or 50 years.

Hemangiomas and vascular malformations

Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that standard cutaneous hemangiomas had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of interest, the hallmark article’s first author was Dr. Margileth, published in 1965 in JAMA!.This was still at a time when the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” as we say in the trade) was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized the distinct variant tumors such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, or hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome was not yet described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden, MD, and colleagues). And for a time, hemangiomas were treated with x-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. It seems that, as a consequence of the use of x-ray therapy and as a backlash from the radiation therapy side effects and potential toxicities, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, with a sensibility that doing nothing might be better than doing the wrong thing.

Over the next 15 years, the recognition of functionally significant hemangiomas, deformation associated with their proliferation, and the recognition of PHACE syndrome made hemangiomas of infancy an area of concern, with systemic steroids and occasionally chemotherapeutic agents (such as vincristine) being used for problematic lesions.

It has now been 12 years since the work of Christine Léauté-Labrèze, MD, et al., from the University of Bordeaux (France), led to the breakthrough of propranolol for hemangioma treatment, profoundly changing hemangioma management to an incredibly effective medical therapy extensively studied, tested in formal clinical trials, and approved by regulatory authorities. And how intriguing that this was pursued after the chance (but skilled) observation that a child who developed hypertension as a side effect of systemic steroids for nasal hemangioma treatment was prescribed propranolol for the hypertension and had his nasal hemangioma rapidly shrink, with a response superior and much quicker than that to corticosteroids.

The evolution of management of hemangiomas has another story within it, that of collaborative research. The Hemangioma Investigator Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development, and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas. Our knowledge of these lesions is now evidence based and broad, and the impact on care tremendous! The HIG has also influenced the practice of pediatricians and other specialists, including otorhinolaryngologists, hematologist/oncologists, and surgeons, is partnering with advocacy groups to support patients and families, and is helping guide patients and families to contribute to ongoing research.

Vascular malformations (VM) reflect an incredible change in our understanding of the developmental pathways and pathophysiology of blood vessel tumors, and, in fact, birthmarks other than vascular lesions! First, important work separated out hemangiomas of infancy and hemangiomalike tumors from vascular malformations, with the thought being that hemangiomas had a rapid growth phase, often arising from lesions that were minimally evident or not evident at birth, unlike malformations, which were “programing errors,” all present at birth and expected to be fairly static with proportionate growth over a lifetime. Approaches to vascular malformations were limited to sclerotherapy, laser, and/or surgery. While this general schema of classification is still useful, our sense of the “why and how” of vascular malformations is remarkably different. Vascular malformations – still usefully subdivided into capillary, lymphatic, venous arteriovenous, or mixed malformations – are mostly associated with inherited or somatic mutations. Mutations are most commonly found in two signal pathways: RAS/MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways, with specific sets of mutations seen in both localized and multifocal lesions, with or without overgrowth or other systemic anomalies. The discovery of specific mutations has led to the possibility of small-molecule inhibitors, many already existing as anticancer drugs, being utilized as targeted therapies for VM.

And similar advances in understanding of other birthmarks, with or without syndromic features, are being made steadily. The mutations in congenital melanocytic nevi, epidermal nevi, acquired tumors (pilomatricomas), and other lesions, along with steady epidemiologic, translational, and clinical work, evolves our knowledge and potential therapies.

Inflammatory skin disorders: Acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris is now recognized as much more common under age 12 than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later, with expert recommendations formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013. Over the past few years, there has been a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance. There are unanswered questions as we evolve our care: How will the new topical antiandrogens be used? Will spironolactone become part of hormonal therapy under age 18? Will the insights on certain strains of Cutibacterium acnes being associated with worse acne translate to microbiome or vaccine-based strategies?

Pediatric psoriasis has suffered, being “behind in the revolution” of biologic agents because of delayed approval of any biologic agent for treatment of pediatric psoriasis in the United States until just a few years ago, and lags behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Only this year have we expanded beyond one biologic agent approved for under age 12 and two for ages 12 and older, with other approvals expected including interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-23 agents. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, with new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis, supplied first by PeDRA and then in the new American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation pediatric psoriasis guidelines .

Pediatric atopic dermatitis (AD) is in its early years of revolution. In the 50-year period of our thought experiment, AD has increased in prevalence from 5% or less of the pediatric population to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, and management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their use of these useful agents. But newer studies are markedly reassuring about their safe use in children.

Steroid phobia, as well as concerns about potential side effects of the TCIs, has resulted in undertreatment of childhood AD. It is quite common to see multiple children during pediatric dermatology office hours with poorly controlled eczema, high body-surface areas of eczema, compromised sleep, secondary infections, and anxiety and depression, especially in our moderate to severe adolescents. The field is “hot” with new topical and systemic agents, including our few years’ experience with topical crisaborole, a phosphodiesterase (PDE)-4 inhibitor; and dupilumab, an IL-4-alpha blocker – the first biologic agent approved for AD and the first systemic agent (other than oral corticosteroids), just extended from 12 years to 6 years of age! As dupilumab gets studied for younger children, other biologics (including IL-13 and IL-31 blockers) are undertaking pediatric and/or adolescent trials, oral and topical JAK inhibitors are including adolescents in core clinical trials, and other novel topical agents are under study, including an aryl-hydrocarbon receptor–modulating agent and other PDE-4 inhibitors.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: From liquid nitrogen to laser, surgery, and multimodal skin care

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. The care of the conditions discussed above, as well as genodermatoses, diagnostic dilemmas, and management of dermatologic manifestations of systemic disease and other conditions, was the “bread and butter” of pediatric dermatology care. When I was in training, my mentor Paul Honig, MD, at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia had a procedure half-day each week, where he would care for a few patients who needed liquid nitrogen therapy for warts, or who needed biopsies. It was uncommon to have a large procedural/surgical part of pediatric dermatology practice. But this is now a routine part of many specialists in the field. How did this change occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser for treatment of port-wine birthmarks in children with minimal scarring, and a seminal article published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1989. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists developed the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age-appropriate manner, with consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota, for example), hair laser, and combinations of lasers, including fractionated CO2 technology, to treat hypertrophic, constrictive and/or deforming scars.

The future

What will pediatric dermatology be like in 10, 20, or 50 years?

I have not yet discussed some of the most challenging diseases in our field, including epidermolysis bullosa, ichthyosis, and neurocutaneous disorders and other genetic skin disorders that have an incredible impact on the lives of affected children and their families, with incredible morbidity and with many conditions that shorten lifespans. But these are the conditions where “the future is happening now,” and we are looking forward to our new gene therapy techniques helping to transform our care.

And other aspects of practice? Will we be doing a large percentage of practice over the phone (or whatever devices we have then – remember, the first iPhone was only released 13 years ago)?

Will our patients be using their own imaging systems to evaluate their nevi and skin growths, and perhaps to diagnose and manage their rashes?

Will we have prevented our inflammatory skin disorders, or “turned them off” in early life with aggressive therapy in infantile life?

I project only that all of us in dermatology will still be a resource to our pediatric patients, from neonate through young adult, through our work of preventing, caring, healing and minimizing disease impact, and hopefully enjoying the pleasures of seeing our patients healthfully develop and evolve! As will our field.

Dr. Eichenfield is professor of dermatology and pediatrics and vice-chair of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield reports financial relationships with 20 pharmaceutical companies that manufacture dermatologic products, including products for the diseases discussed here.

As part of the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News, it is intriguing to think about where a time machine journey 5 decades back would find the field of pediatric dermatology, and to assess the changes in the specialty during the time that Dermatology News (operating then as “Skin & Allergy News”) has been reporting on innovations and changes in the practice of dermatology.

So, starting . It was not until 3 years later, in October 1973 in Mexico City, that the first international symposium on Pediatric Dermatology was held, and the International Society for Pediatric Dermatology was founded. I reached out to Andrew Margileth, MD, 100 years old this past July, and still active voluntary faculty in pediatric dermatology at the University of Miami, to help me “reach back” to those days. Dr. Margileth commented on how the first symposium was “brilliantly orchestrated by Ramon Ruiz-Maldonado,” from the National Institute of Paediatrics in Mexico, and that it was his “Aha moment for future practice!” That meeting spurred discussions on the development of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology the next year, with Alvin Jacobs, MD; Samuel Weinberg, MD; Nancy Esterly, MD; Sidney Hurwitz, MD; William Weston, MD; and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers,” and the society was officially established in 1975.

The field of pediatric dermatology was fairly “infantile” 50 years ago, with few practitioners. But the early leaders in the field recognized that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits included skin problems, and that there was limited training for dermatologists, as well as pediatricians, about skin diseases in children. There were clearly clinical and educational needs to establish a subspecialty of pediatric dermatology, and over the next 1-2 decades, the field expanded. The journal Pediatric Dermatology was established (in 1982), the Section on Dermatology was established by the American Academy of Pediatrics (in 1986), and fellowship programs were launched at select academic centers. And it was 30 years into our timeline before the formal subspecialty of pediatric dermatology was established through the American Board of Dermatology (2000).

The field of pediatric dermatology has evolved and matured rapidly. Standard reference textbooks have been developed in the United States and around the world (and of course, online). Pediatric dermatology is an essential part of the core curriculum for dermatologist trainees. Organizations promoting pediatric research have developed to influence basic, translational, and clinical research in conditions in neonates through adolescents, such as the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA). And meetings throughout the world now feature pediatric dermatology sessions and help to spread the advances in the diagnosis and management of pediatric skin disorders.

The practice of pediatric dermatology: How has it changed?

It is beyond the scope of this article to try to comprehensively review all of the changes in pediatric dermatology practice. But review of the evolution of a few disease states (choices influenced by my discussions with my 100-year old history guide, Dr. Margileth) displays examples of where we have been, and where we are going in our next 5, 10, or 50 years.

Hemangiomas and vascular malformations

Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that standard cutaneous hemangiomas had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of interest, the hallmark article’s first author was Dr. Margileth, published in 1965 in JAMA!.This was still at a time when the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” as we say in the trade) was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized the distinct variant tumors such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, or hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome was not yet described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden, MD, and colleagues). And for a time, hemangiomas were treated with x-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. It seems that, as a consequence of the use of x-ray therapy and as a backlash from the radiation therapy side effects and potential toxicities, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, with a sensibility that doing nothing might be better than doing the wrong thing.

Over the next 15 years, the recognition of functionally significant hemangiomas, deformation associated with their proliferation, and the recognition of PHACE syndrome made hemangiomas of infancy an area of concern, with systemic steroids and occasionally chemotherapeutic agents (such as vincristine) being used for problematic lesions.

It has now been 12 years since the work of Christine Léauté-Labrèze, MD, et al., from the University of Bordeaux (France), led to the breakthrough of propranolol for hemangioma treatment, profoundly changing hemangioma management to an incredibly effective medical therapy extensively studied, tested in formal clinical trials, and approved by regulatory authorities. And how intriguing that this was pursued after the chance (but skilled) observation that a child who developed hypertension as a side effect of systemic steroids for nasal hemangioma treatment was prescribed propranolol for the hypertension and had his nasal hemangioma rapidly shrink, with a response superior and much quicker than that to corticosteroids.

The evolution of management of hemangiomas has another story within it, that of collaborative research. The Hemangioma Investigator Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development, and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas. Our knowledge of these lesions is now evidence based and broad, and the impact on care tremendous! The HIG has also influenced the practice of pediatricians and other specialists, including otorhinolaryngologists, hematologist/oncologists, and surgeons, is partnering with advocacy groups to support patients and families, and is helping guide patients and families to contribute to ongoing research.

Vascular malformations (VM) reflect an incredible change in our understanding of the developmental pathways and pathophysiology of blood vessel tumors, and, in fact, birthmarks other than vascular lesions! First, important work separated out hemangiomas of infancy and hemangiomalike tumors from vascular malformations, with the thought being that hemangiomas had a rapid growth phase, often arising from lesions that were minimally evident or not evident at birth, unlike malformations, which were “programing errors,” all present at birth and expected to be fairly static with proportionate growth over a lifetime. Approaches to vascular malformations were limited to sclerotherapy, laser, and/or surgery. While this general schema of classification is still useful, our sense of the “why and how” of vascular malformations is remarkably different. Vascular malformations – still usefully subdivided into capillary, lymphatic, venous arteriovenous, or mixed malformations – are mostly associated with inherited or somatic mutations. Mutations are most commonly found in two signal pathways: RAS/MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways, with specific sets of mutations seen in both localized and multifocal lesions, with or without overgrowth or other systemic anomalies. The discovery of specific mutations has led to the possibility of small-molecule inhibitors, many already existing as anticancer drugs, being utilized as targeted therapies for VM.

And similar advances in understanding of other birthmarks, with or without syndromic features, are being made steadily. The mutations in congenital melanocytic nevi, epidermal nevi, acquired tumors (pilomatricomas), and other lesions, along with steady epidemiologic, translational, and clinical work, evolves our knowledge and potential therapies.

Inflammatory skin disorders: Acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris is now recognized as much more common under age 12 than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later, with expert recommendations formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013. Over the past few years, there has been a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance. There are unanswered questions as we evolve our care: How will the new topical antiandrogens be used? Will spironolactone become part of hormonal therapy under age 18? Will the insights on certain strains of Cutibacterium acnes being associated with worse acne translate to microbiome or vaccine-based strategies?

Pediatric psoriasis has suffered, being “behind in the revolution” of biologic agents because of delayed approval of any biologic agent for treatment of pediatric psoriasis in the United States until just a few years ago, and lags behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Only this year have we expanded beyond one biologic agent approved for under age 12 and two for ages 12 and older, with other approvals expected including interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-23 agents. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, with new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis, supplied first by PeDRA and then in the new American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation pediatric psoriasis guidelines .

Pediatric atopic dermatitis (AD) is in its early years of revolution. In the 50-year period of our thought experiment, AD has increased in prevalence from 5% or less of the pediatric population to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, and management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their use of these useful agents. But newer studies are markedly reassuring about their safe use in children.

Steroid phobia, as well as concerns about potential side effects of the TCIs, has resulted in undertreatment of childhood AD. It is quite common to see multiple children during pediatric dermatology office hours with poorly controlled eczema, high body-surface areas of eczema, compromised sleep, secondary infections, and anxiety and depression, especially in our moderate to severe adolescents. The field is “hot” with new topical and systemic agents, including our few years’ experience with topical crisaborole, a phosphodiesterase (PDE)-4 inhibitor; and dupilumab, an IL-4-alpha blocker – the first biologic agent approved for AD and the first systemic agent (other than oral corticosteroids), just extended from 12 years to 6 years of age! As dupilumab gets studied for younger children, other biologics (including IL-13 and IL-31 blockers) are undertaking pediatric and/or adolescent trials, oral and topical JAK inhibitors are including adolescents in core clinical trials, and other novel topical agents are under study, including an aryl-hydrocarbon receptor–modulating agent and other PDE-4 inhibitors.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: From liquid nitrogen to laser, surgery, and multimodal skin care

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. The care of the conditions discussed above, as well as genodermatoses, diagnostic dilemmas, and management of dermatologic manifestations of systemic disease and other conditions, was the “bread and butter” of pediatric dermatology care. When I was in training, my mentor Paul Honig, MD, at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia had a procedure half-day each week, where he would care for a few patients who needed liquid nitrogen therapy for warts, or who needed biopsies. It was uncommon to have a large procedural/surgical part of pediatric dermatology practice. But this is now a routine part of many specialists in the field. How did this change occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser for treatment of port-wine birthmarks in children with minimal scarring, and a seminal article published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1989. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists developed the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age-appropriate manner, with consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota, for example), hair laser, and combinations of lasers, including fractionated CO2 technology, to treat hypertrophic, constrictive and/or deforming scars.

The future

What will pediatric dermatology be like in 10, 20, or 50 years?

I have not yet discussed some of the most challenging diseases in our field, including epidermolysis bullosa, ichthyosis, and neurocutaneous disorders and other genetic skin disorders that have an incredible impact on the lives of affected children and their families, with incredible morbidity and with many conditions that shorten lifespans. But these are the conditions where “the future is happening now,” and we are looking forward to our new gene therapy techniques helping to transform our care.

And other aspects of practice? Will we be doing a large percentage of practice over the phone (or whatever devices we have then – remember, the first iPhone was only released 13 years ago)?

Will our patients be using their own imaging systems to evaluate their nevi and skin growths, and perhaps to diagnose and manage their rashes?

Will we have prevented our inflammatory skin disorders, or “turned them off” in early life with aggressive therapy in infantile life?

I project only that all of us in dermatology will still be a resource to our pediatric patients, from neonate through young adult, through our work of preventing, caring, healing and minimizing disease impact, and hopefully enjoying the pleasures of seeing our patients healthfully develop and evolve! As will our field.

Dr. Eichenfield is professor of dermatology and pediatrics and vice-chair of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield reports financial relationships with 20 pharmaceutical companies that manufacture dermatologic products, including products for the diseases discussed here.

As part of the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News, it is intriguing to think about where a time machine journey 5 decades back would find the field of pediatric dermatology, and to assess the changes in the specialty during the time that Dermatology News (operating then as “Skin & Allergy News”) has been reporting on innovations and changes in the practice of dermatology.

So, starting . It was not until 3 years later, in October 1973 in Mexico City, that the first international symposium on Pediatric Dermatology was held, and the International Society for Pediatric Dermatology was founded. I reached out to Andrew Margileth, MD, 100 years old this past July, and still active voluntary faculty in pediatric dermatology at the University of Miami, to help me “reach back” to those days. Dr. Margileth commented on how the first symposium was “brilliantly orchestrated by Ramon Ruiz-Maldonado,” from the National Institute of Paediatrics in Mexico, and that it was his “Aha moment for future practice!” That meeting spurred discussions on the development of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology the next year, with Alvin Jacobs, MD; Samuel Weinberg, MD; Nancy Esterly, MD; Sidney Hurwitz, MD; William Weston, MD; and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers,” and the society was officially established in 1975.

The field of pediatric dermatology was fairly “infantile” 50 years ago, with few practitioners. But the early leaders in the field recognized that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits included skin problems, and that there was limited training for dermatologists, as well as pediatricians, about skin diseases in children. There were clearly clinical and educational needs to establish a subspecialty of pediatric dermatology, and over the next 1-2 decades, the field expanded. The journal Pediatric Dermatology was established (in 1982), the Section on Dermatology was established by the American Academy of Pediatrics (in 1986), and fellowship programs were launched at select academic centers. And it was 30 years into our timeline before the formal subspecialty of pediatric dermatology was established through the American Board of Dermatology (2000).

The field of pediatric dermatology has evolved and matured rapidly. Standard reference textbooks have been developed in the United States and around the world (and of course, online). Pediatric dermatology is an essential part of the core curriculum for dermatologist trainees. Organizations promoting pediatric research have developed to influence basic, translational, and clinical research in conditions in neonates through adolescents, such as the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA). And meetings throughout the world now feature pediatric dermatology sessions and help to spread the advances in the diagnosis and management of pediatric skin disorders.

The practice of pediatric dermatology: How has it changed?

It is beyond the scope of this article to try to comprehensively review all of the changes in pediatric dermatology practice. But review of the evolution of a few disease states (choices influenced by my discussions with my 100-year old history guide, Dr. Margileth) displays examples of where we have been, and where we are going in our next 5, 10, or 50 years.

Hemangiomas and vascular malformations

Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that standard cutaneous hemangiomas had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of interest, the hallmark article’s first author was Dr. Margileth, published in 1965 in JAMA!.This was still at a time when the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” as we say in the trade) was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized the distinct variant tumors such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, or hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome was not yet described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden, MD, and colleagues). And for a time, hemangiomas were treated with x-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. It seems that, as a consequence of the use of x-ray therapy and as a backlash from the radiation therapy side effects and potential toxicities, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, with a sensibility that doing nothing might be better than doing the wrong thing.

Over the next 15 years, the recognition of functionally significant hemangiomas, deformation associated with their proliferation, and the recognition of PHACE syndrome made hemangiomas of infancy an area of concern, with systemic steroids and occasionally chemotherapeutic agents (such as vincristine) being used for problematic lesions.

It has now been 12 years since the work of Christine Léauté-Labrèze, MD, et al., from the University of Bordeaux (France), led to the breakthrough of propranolol for hemangioma treatment, profoundly changing hemangioma management to an incredibly effective medical therapy extensively studied, tested in formal clinical trials, and approved by regulatory authorities. And how intriguing that this was pursued after the chance (but skilled) observation that a child who developed hypertension as a side effect of systemic steroids for nasal hemangioma treatment was prescribed propranolol for the hypertension and had his nasal hemangioma rapidly shrink, with a response superior and much quicker than that to corticosteroids.

The evolution of management of hemangiomas has another story within it, that of collaborative research. The Hemangioma Investigator Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development, and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas. Our knowledge of these lesions is now evidence based and broad, and the impact on care tremendous! The HIG has also influenced the practice of pediatricians and other specialists, including otorhinolaryngologists, hematologist/oncologists, and surgeons, is partnering with advocacy groups to support patients and families, and is helping guide patients and families to contribute to ongoing research.

Vascular malformations (VM) reflect an incredible change in our understanding of the developmental pathways and pathophysiology of blood vessel tumors, and, in fact, birthmarks other than vascular lesions! First, important work separated out hemangiomas of infancy and hemangiomalike tumors from vascular malformations, with the thought being that hemangiomas had a rapid growth phase, often arising from lesions that were minimally evident or not evident at birth, unlike malformations, which were “programing errors,” all present at birth and expected to be fairly static with proportionate growth over a lifetime. Approaches to vascular malformations were limited to sclerotherapy, laser, and/or surgery. While this general schema of classification is still useful, our sense of the “why and how” of vascular malformations is remarkably different. Vascular malformations – still usefully subdivided into capillary, lymphatic, venous arteriovenous, or mixed malformations – are mostly associated with inherited or somatic mutations. Mutations are most commonly found in two signal pathways: RAS/MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways, with specific sets of mutations seen in both localized and multifocal lesions, with or without overgrowth or other systemic anomalies. The discovery of specific mutations has led to the possibility of small-molecule inhibitors, many already existing as anticancer drugs, being utilized as targeted therapies for VM.

And similar advances in understanding of other birthmarks, with or without syndromic features, are being made steadily. The mutations in congenital melanocytic nevi, epidermal nevi, acquired tumors (pilomatricomas), and other lesions, along with steady epidemiologic, translational, and clinical work, evolves our knowledge and potential therapies.

Inflammatory skin disorders: Acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris is now recognized as much more common under age 12 than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later, with expert recommendations formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013. Over the past few years, there has been a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance. There are unanswered questions as we evolve our care: How will the new topical antiandrogens be used? Will spironolactone become part of hormonal therapy under age 18? Will the insights on certain strains of Cutibacterium acnes being associated with worse acne translate to microbiome or vaccine-based strategies?

Pediatric psoriasis has suffered, being “behind in the revolution” of biologic agents because of delayed approval of any biologic agent for treatment of pediatric psoriasis in the United States until just a few years ago, and lags behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Only this year have we expanded beyond one biologic agent approved for under age 12 and two for ages 12 and older, with other approvals expected including interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-23 agents. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, with new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis, supplied first by PeDRA and then in the new American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation pediatric psoriasis guidelines .

Pediatric atopic dermatitis (AD) is in its early years of revolution. In the 50-year period of our thought experiment, AD has increased in prevalence from 5% or less of the pediatric population to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, and management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their use of these useful agents. But newer studies are markedly reassuring about their safe use in children.

Steroid phobia, as well as concerns about potential side effects of the TCIs, has resulted in undertreatment of childhood AD. It is quite common to see multiple children during pediatric dermatology office hours with poorly controlled eczema, high body-surface areas of eczema, compromised sleep, secondary infections, and anxiety and depression, especially in our moderate to severe adolescents. The field is “hot” with new topical and systemic agents, including our few years’ experience with topical crisaborole, a phosphodiesterase (PDE)-4 inhibitor; and dupilumab, an IL-4-alpha blocker – the first biologic agent approved for AD and the first systemic agent (other than oral corticosteroids), just extended from 12 years to 6 years of age! As dupilumab gets studied for younger children, other biologics (including IL-13 and IL-31 blockers) are undertaking pediatric and/or adolescent trials, oral and topical JAK inhibitors are including adolescents in core clinical trials, and other novel topical agents are under study, including an aryl-hydrocarbon receptor–modulating agent and other PDE-4 inhibitors.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: From liquid nitrogen to laser, surgery, and multimodal skin care

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. The care of the conditions discussed above, as well as genodermatoses, diagnostic dilemmas, and management of dermatologic manifestations of systemic disease and other conditions, was the “bread and butter” of pediatric dermatology care. When I was in training, my mentor Paul Honig, MD, at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia had a procedure half-day each week, where he would care for a few patients who needed liquid nitrogen therapy for warts, or who needed biopsies. It was uncommon to have a large procedural/surgical part of pediatric dermatology practice. But this is now a routine part of many specialists in the field. How did this change occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser for treatment of port-wine birthmarks in children with minimal scarring, and a seminal article published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1989. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists developed the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age-appropriate manner, with consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota, for example), hair laser, and combinations of lasers, including fractionated CO2 technology, to treat hypertrophic, constrictive and/or deforming scars.

The future

What will pediatric dermatology be like in 10, 20, or 50 years?

I have not yet discussed some of the most challenging diseases in our field, including epidermolysis bullosa, ichthyosis, and neurocutaneous disorders and other genetic skin disorders that have an incredible impact on the lives of affected children and their families, with incredible morbidity and with many conditions that shorten lifespans. But these are the conditions where “the future is happening now,” and we are looking forward to our new gene therapy techniques helping to transform our care.

And other aspects of practice? Will we be doing a large percentage of practice over the phone (or whatever devices we have then – remember, the first iPhone was only released 13 years ago)?

Will our patients be using their own imaging systems to evaluate their nevi and skin growths, and perhaps to diagnose and manage their rashes?

Will we have prevented our inflammatory skin disorders, or “turned them off” in early life with aggressive therapy in infantile life?

I project only that all of us in dermatology will still be a resource to our pediatric patients, from neonate through young adult, through our work of preventing, caring, healing and minimizing disease impact, and hopefully enjoying the pleasures of seeing our patients healthfully develop and evolve! As will our field.

Dr. Eichenfield is professor of dermatology and pediatrics and vice-chair of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield reports financial relationships with 20 pharmaceutical companies that manufacture dermatologic products, including products for the diseases discussed here.