User login

- The process for evaluating treatment refusal should be consistent regardless of setting, problem (ie, medical or psychiatric), type of patient, or practitioner.

- Assess decisional capacity, psychiatric dangerousness, and medical risk in all cases of treatment refusal while addressing potential causes of treatment refusal.

- Based on these assessments, choose between: a) respecting the treatment refusal, b) obtaining a surrogate, or c) mandating hospitalization and possibly treatment.

An 80-year-old woman with diabetes who has been your patient for many years is in failing health and may need dialysis for deteriorating kidney function. She refuses even to consider further evaluation.

A 37-year-old man has, according to his family, become increasingly depressed and makes comments suggesting suicidal ideation. They are afraid for his safety. He says he’s just going through a rough period and doesn’t need help.

Would you be prepared to handle instances of treatment refusal such as these? Treatment refusal can be challenging, creating conflicts among patients, families, and health care providers, and raising important ethical considerations. A patient’s autonomy may be undermined if her wishes are overridden. Inappropriately confining, restraining, or treating patients may cause harm. Failing to obtain a surrogate when indicated may result in a missed opportunity to benefit a patient. Refusal of treatment, when unaddressed or mishandled, may lead to patient dissatisfaction, substandard care, increased litigation, or disparities in care.

Clearer guidelines are needed to help clinicians evaluate and manage patients who refuse treatment. Building on previous work in treatment refusal, informed consent, and competency theory, we propose an approach to treatment refusal that provides 3 unique contributions:

- First, our model integrates medical and psychiatric treatment refusal practices—usually found in separate literature bases—into one model.

- Second, it emphasizes that evaluations of both decisional capacity and dangerousness (both defined later) are crucial to determining the appropriate response to treatment refusal.

- Third, it provides concrete guidance for how to decide between 3 actions: 1) respect the treatment refusal, 2) obtain a surrogate, or 3) mandate hospitalization and possibly treatment.

How to assess and manage treatment refusal

Step 1: Evaluate both decisional capacity and dangerousness

Grisso and Appelbaum have described an empirically tested model of how to evaluate decisional capacity.1Decisional capacity refers to the ability to make a choice about treatment, and it is determined by the presence and extent of functional abilities, which are hierarchical, from the simplest to the most complex:

- Making a choice (“I’d like to have the cardiac catheterization”)

- Understanding relevant details, such as diagnosis, prognosis, the benefits and burdens of different treatment alternatives, and what will happen without treatment

- Appreciating that the relevant details apply to oneself and will mean something for one’s own future

- Rationally describing why a choice was made (such as explaining why one would prefer a particular set of risks, benefits, or burdens from one treatment alternative over another).

Many factors may interfere with these abilities and they should be assessed,1 but additional discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

Not all patients with mental illness have impaired decisional capacity. On the contrary, there is significant variability in the decisional capacity of people with serious mental illness.2 One instrument to evaluate decisional capacity for treatment decisions has been studied, but time constraints may limit its widespread application in clinical practice.3

Dangerousness in the clinical setting is generally defined as the intent to harm oneself or others, creating imminent risk. For the purposes of our model, this will be called “psychiatric dangerousness.” Other sources describe the assessment of psychiatric dangerousness in more detail,4 but the assessment typically includes a thorough psychosocial history, an evaluation for mental illness, a determination of risk factors for suicide, and often corroborating history from family or friends. “Medical dangerousness” is defined as the risk of morbidity or mortality that accompanies medical intervention or non-intervention.

In cases of treatment refusal, explicitly assess both decisional capacity and dangerousness. There are 3 benefits in doing so. First, it helps avoid the tendency to assess dangerousness only in the psychiatric context and decisional capacity in the general medical context. Second, it provides a useful way to approach treatment refusal when the cause of symptoms or complaints is ambiguous. Third, it helps when a patient exhibits both medical and psychiatric symptoms of illness.

Step 2: Determine the need for involuntary hospitalization and treatment

The ideal threshold for involuntary confinement is the point at which those who will harm themselves or others are confined and protected, while those who will not harm themselves or others are not. Determining the ideal threshold for involuntary treatment is difficult. Besides the challenges in predicting dangerousness,5 this determination involves a balance between potentially competing goals: respecting individual liberties, enhancing quality of life, and protecting patients and others from harm.

In general, there is greater justification for involuntary hospitalization with increasing “psychiatric dangerousness.” States vary on what requirements must be met for involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. Many jurisdictions have additional requirements to force psychiatric treatment; in some jurisdictions, forcing psychiatric treatment is not permitted.

Step 3: Determine the need for a surrogate decision-maker

The strength of the case for surrogate decision-making increases as decisional capacity decreases. A surrogate decision-maker is the person authorized to make decisions for a person who is not fully autonomous because of impaired decisional capacity. The ethical justification for obtaining a surrogate is to respect the patient’s prior ability to be informed and make a choice. Some patients share decision-making with other family or friends and this should be respected.

In our view, a surrogate should be obtained for a patient with impaired decisional capacity even when significant “psychiatric dangerousness” is present and involuntary hospitalization or treatment is pursued. The principle of equal respect for persons supports the view that since incompetent patients with medical problems are afforded a surrogate, so should incompetent patients with psychiatric problems.

Some might argue that the judge ordering the mandatory hospitalization or treatment is the surrogate. However, others who know the patient better and are more familiar with their values are more likely to provide authentic substituted judgment. At the same time, safety concerns for the patient (in the case of suicidal intent) or others (in the case of homicidal intent) require that surrogate decision-making be restricted. Surprisingly, no law or regulation in the US, to our knowledge, mandates appointing a surrogate for a patient who is involuntarily hospitalized or treated.

Managing treatment refusal in practice

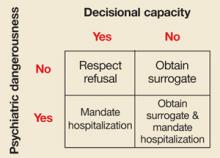

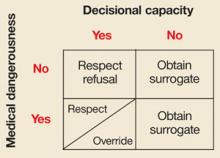

Evaluating decisional capacity and dangerousness leads to 3 possible decisions: 1) respect the treatment refusal, 2) obtain a surrogate, or 3) mandate hospitalization and possibly treatment. FIGURES 1 AND 2 depict such decisions for psychiatric and medical dangerousness, respectively. The important question during evaluation is not, “Is there decisional capacity or dangerousness?” but is rather, “How much decisional capacity or dangerousness is present?” Even if different evaluators agree which decision-making abilities are present or how much psychiatric dangerousness exists, a value judgment must be made to decide the threshold at which a surrogate is obtained or the court is petitioned for involuntary hospitalization or treatment.

Similarities in the assessments of medical and psychiatric dangerousness.

When a patient exhibits adequate decisional capacity and insufficient dangerousness of either type, treatment refusal is respected. When decisional capacity is judged to be impaired, a surrogate should be obtained regardless of the type of dangerousness that is present.

FIGURE 1

Decisional capacity and psychiatric dangerousness

In assessing a patient’s decisional capacity and level of psychiatric dangerousness, we depart from traditional practice (lower right-hand box) and recommend obtaining a surrogate decision-maker when the patient has inadequate decisional capacity.

FIGURE 2

Decisional capacity and medical dangerousness

In assessing a patient’s decisional capacity and level of medical dangerousness, our model considers the clinical context in judging whether to override or respect a patient’s decision (lower left-hand box).

Decisional capacity

Differences in the assessments. Two boxes in the figures deserve comment. First, the bottom right box of FIGURE 1 recommends a departure from current practice. As described earlier, we recommend obtaining a surrogate for patients who have impaired decisional capacity and are involuntarily hospitalized for psychiatric dangerousness. Second, in the bottom left box of FIGURE 2, treatment refusal by a patient who has decisional capacity and “medical dangerousness” may be respected or overridden depending on contextual factors. The long history of respect for liberty, and the requirement not to invade another’s body without consent generally supports respecting treatment refusal.

When decisions may be overridden in a patient with adequate decisional capacity and medical dangerousness. During a public health emergency, such as a tuberculosis or SARS outbreak, ensuring the public’s safety may outweigh respect for individual liberties. When someone with tuberculosis refuses treatment and has adequate decisional capacity, legal precedent and ethical justification exist to defend involuntary confinement or treatment in certain circumstances.6

When the threshold for adequate decisional capacity changes based on the level of medical dangerousness. With increasing medical dangerousness, a given level of decisional capacity may be regarded as inadequate, and treatment refusal may be appropriately questioned and consideration given to naming a surrogate.7,8 Alternatively, when there is little “medical dangerousness,” less decisional capacity may be required for a treatment refusal to be respected. This approach is controversial because it involves a modifiable notion of decisional capacity.9

In addition, this approach is not appropriate in all contexts. For example, in patients who are imminently dying with irreversible terminal illness, “medical dangerousness” may be very high, but the threshold for adequate decisional capacity should not necessarily be very high.

Dealing with uncertainty

Sometimes the degree of “medical dangerousness” is difficult to quantify, in part because the diagnosis may be uncertain; or even when the diagnosis is known, prognostication may be difficult.10

In instances of uncertainty, considering the possibility that there may be a serious underlying condition is important both medically (in case immediate intervention can prevent a negative outcome) and ethically (to benefit the patient and preserve autonomy by preventing morbidity that may be impairing). Thus, shifting the standard for decisional capacity to require a higher level of understanding and appreciation may be justified.

In such cases, even though a patient has some level of decisional capacity, a surrogate may be needed. One approach might be to attempt shared decision-making between the patient and surrogate, although ultimate decision-making should be left to the surrogate.

Careful documentation is important

As with other medical issues, in cases of treatment refusal, thoroughly document the process, whether or not treatment refusal is ultimately honored. Note findings from the evaluation including decisional capacity and medical and psychiatric dangerousness, thinking associated with the assessment, and specific management plans.

Record any decision for involuntary hospitalization or treatment because of psychiatric dangerousness or the need for a surrogate decision-maker because of impaired decisional capacity. Finally, describe your reasons for a course of action in the special situations noted above.

Benefits of this model

This approach to treatment refusal is consistent and involves clear standards and processes for evaluation, regardless of setting, problem, type of patient, or practitioner. It facilitates respect for persons, equal treatment independent of diagnosis, and appropriate involvement of surrogate decision-makers and the courts.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this work have been presented at the following meetings:

Bekelman D, Carrese J (2003). Treatment refusal and decisional competence assessment. Concurrent Session, Clinical Ethics Consultation: First International Summit, Cleveland, Ohio.

Bekelman D (2002). Treatment refusal: Conceptual models and clinical approaches. Workshop, 49th annual meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, Tucson, Arizona.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Bekelman, MD, MPH, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, 4200 East 9th Avenue, B180, Denver, CO 80262. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

2. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. III: Abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law Hum Behav 1995;19:149-174.

3. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1415–1419. The tool itself can be found online at: www.prpress.com/books/mact-setfr.html.

4. Packman WL, Marlitt RE, Bongar B, O’Connor PT. A comprehensive and concise assessment of suicide risk. Behav Sci Law 2004;22:667.-

5. Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1994.

6. Gostin LO. Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

7. Buchanan AE, Brock DW. Deciding for Others: The Ethics of Surrogate Decision Making. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press,1989.

8. Roth LH, Meisel A, Lidz CW. Tests of competency to consent to treatment. Am J Psych 1977;134:279-284.

9. Beauchamp TL, Childress CF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

10. Christakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1999.

- The process for evaluating treatment refusal should be consistent regardless of setting, problem (ie, medical or psychiatric), type of patient, or practitioner.

- Assess decisional capacity, psychiatric dangerousness, and medical risk in all cases of treatment refusal while addressing potential causes of treatment refusal.

- Based on these assessments, choose between: a) respecting the treatment refusal, b) obtaining a surrogate, or c) mandating hospitalization and possibly treatment.

An 80-year-old woman with diabetes who has been your patient for many years is in failing health and may need dialysis for deteriorating kidney function. She refuses even to consider further evaluation.

A 37-year-old man has, according to his family, become increasingly depressed and makes comments suggesting suicidal ideation. They are afraid for his safety. He says he’s just going through a rough period and doesn’t need help.

Would you be prepared to handle instances of treatment refusal such as these? Treatment refusal can be challenging, creating conflicts among patients, families, and health care providers, and raising important ethical considerations. A patient’s autonomy may be undermined if her wishes are overridden. Inappropriately confining, restraining, or treating patients may cause harm. Failing to obtain a surrogate when indicated may result in a missed opportunity to benefit a patient. Refusal of treatment, when unaddressed or mishandled, may lead to patient dissatisfaction, substandard care, increased litigation, or disparities in care.

Clearer guidelines are needed to help clinicians evaluate and manage patients who refuse treatment. Building on previous work in treatment refusal, informed consent, and competency theory, we propose an approach to treatment refusal that provides 3 unique contributions:

- First, our model integrates medical and psychiatric treatment refusal practices—usually found in separate literature bases—into one model.

- Second, it emphasizes that evaluations of both decisional capacity and dangerousness (both defined later) are crucial to determining the appropriate response to treatment refusal.

- Third, it provides concrete guidance for how to decide between 3 actions: 1) respect the treatment refusal, 2) obtain a surrogate, or 3) mandate hospitalization and possibly treatment.

How to assess and manage treatment refusal

Step 1: Evaluate both decisional capacity and dangerousness

Grisso and Appelbaum have described an empirically tested model of how to evaluate decisional capacity.1Decisional capacity refers to the ability to make a choice about treatment, and it is determined by the presence and extent of functional abilities, which are hierarchical, from the simplest to the most complex:

- Making a choice (“I’d like to have the cardiac catheterization”)

- Understanding relevant details, such as diagnosis, prognosis, the benefits and burdens of different treatment alternatives, and what will happen without treatment

- Appreciating that the relevant details apply to oneself and will mean something for one’s own future

- Rationally describing why a choice was made (such as explaining why one would prefer a particular set of risks, benefits, or burdens from one treatment alternative over another).

Many factors may interfere with these abilities and they should be assessed,1 but additional discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

Not all patients with mental illness have impaired decisional capacity. On the contrary, there is significant variability in the decisional capacity of people with serious mental illness.2 One instrument to evaluate decisional capacity for treatment decisions has been studied, but time constraints may limit its widespread application in clinical practice.3

Dangerousness in the clinical setting is generally defined as the intent to harm oneself or others, creating imminent risk. For the purposes of our model, this will be called “psychiatric dangerousness.” Other sources describe the assessment of psychiatric dangerousness in more detail,4 but the assessment typically includes a thorough psychosocial history, an evaluation for mental illness, a determination of risk factors for suicide, and often corroborating history from family or friends. “Medical dangerousness” is defined as the risk of morbidity or mortality that accompanies medical intervention or non-intervention.

In cases of treatment refusal, explicitly assess both decisional capacity and dangerousness. There are 3 benefits in doing so. First, it helps avoid the tendency to assess dangerousness only in the psychiatric context and decisional capacity in the general medical context. Second, it provides a useful way to approach treatment refusal when the cause of symptoms or complaints is ambiguous. Third, it helps when a patient exhibits both medical and psychiatric symptoms of illness.

Step 2: Determine the need for involuntary hospitalization and treatment

The ideal threshold for involuntary confinement is the point at which those who will harm themselves or others are confined and protected, while those who will not harm themselves or others are not. Determining the ideal threshold for involuntary treatment is difficult. Besides the challenges in predicting dangerousness,5 this determination involves a balance between potentially competing goals: respecting individual liberties, enhancing quality of life, and protecting patients and others from harm.

In general, there is greater justification for involuntary hospitalization with increasing “psychiatric dangerousness.” States vary on what requirements must be met for involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. Many jurisdictions have additional requirements to force psychiatric treatment; in some jurisdictions, forcing psychiatric treatment is not permitted.

Step 3: Determine the need for a surrogate decision-maker

The strength of the case for surrogate decision-making increases as decisional capacity decreases. A surrogate decision-maker is the person authorized to make decisions for a person who is not fully autonomous because of impaired decisional capacity. The ethical justification for obtaining a surrogate is to respect the patient’s prior ability to be informed and make a choice. Some patients share decision-making with other family or friends and this should be respected.

In our view, a surrogate should be obtained for a patient with impaired decisional capacity even when significant “psychiatric dangerousness” is present and involuntary hospitalization or treatment is pursued. The principle of equal respect for persons supports the view that since incompetent patients with medical problems are afforded a surrogate, so should incompetent patients with psychiatric problems.

Some might argue that the judge ordering the mandatory hospitalization or treatment is the surrogate. However, others who know the patient better and are more familiar with their values are more likely to provide authentic substituted judgment. At the same time, safety concerns for the patient (in the case of suicidal intent) or others (in the case of homicidal intent) require that surrogate decision-making be restricted. Surprisingly, no law or regulation in the US, to our knowledge, mandates appointing a surrogate for a patient who is involuntarily hospitalized or treated.

Managing treatment refusal in practice

Evaluating decisional capacity and dangerousness leads to 3 possible decisions: 1) respect the treatment refusal, 2) obtain a surrogate, or 3) mandate hospitalization and possibly treatment. FIGURES 1 AND 2 depict such decisions for psychiatric and medical dangerousness, respectively. The important question during evaluation is not, “Is there decisional capacity or dangerousness?” but is rather, “How much decisional capacity or dangerousness is present?” Even if different evaluators agree which decision-making abilities are present or how much psychiatric dangerousness exists, a value judgment must be made to decide the threshold at which a surrogate is obtained or the court is petitioned for involuntary hospitalization or treatment.

Similarities in the assessments of medical and psychiatric dangerousness.

When a patient exhibits adequate decisional capacity and insufficient dangerousness of either type, treatment refusal is respected. When decisional capacity is judged to be impaired, a surrogate should be obtained regardless of the type of dangerousness that is present.

FIGURE 1

Decisional capacity and psychiatric dangerousness

In assessing a patient’s decisional capacity and level of psychiatric dangerousness, we depart from traditional practice (lower right-hand box) and recommend obtaining a surrogate decision-maker when the patient has inadequate decisional capacity.

FIGURE 2

Decisional capacity and medical dangerousness

In assessing a patient’s decisional capacity and level of medical dangerousness, our model considers the clinical context in judging whether to override or respect a patient’s decision (lower left-hand box).

Decisional capacity

Differences in the assessments. Two boxes in the figures deserve comment. First, the bottom right box of FIGURE 1 recommends a departure from current practice. As described earlier, we recommend obtaining a surrogate for patients who have impaired decisional capacity and are involuntarily hospitalized for psychiatric dangerousness. Second, in the bottom left box of FIGURE 2, treatment refusal by a patient who has decisional capacity and “medical dangerousness” may be respected or overridden depending on contextual factors. The long history of respect for liberty, and the requirement not to invade another’s body without consent generally supports respecting treatment refusal.

When decisions may be overridden in a patient with adequate decisional capacity and medical dangerousness. During a public health emergency, such as a tuberculosis or SARS outbreak, ensuring the public’s safety may outweigh respect for individual liberties. When someone with tuberculosis refuses treatment and has adequate decisional capacity, legal precedent and ethical justification exist to defend involuntary confinement or treatment in certain circumstances.6

When the threshold for adequate decisional capacity changes based on the level of medical dangerousness. With increasing medical dangerousness, a given level of decisional capacity may be regarded as inadequate, and treatment refusal may be appropriately questioned and consideration given to naming a surrogate.7,8 Alternatively, when there is little “medical dangerousness,” less decisional capacity may be required for a treatment refusal to be respected. This approach is controversial because it involves a modifiable notion of decisional capacity.9

In addition, this approach is not appropriate in all contexts. For example, in patients who are imminently dying with irreversible terminal illness, “medical dangerousness” may be very high, but the threshold for adequate decisional capacity should not necessarily be very high.

Dealing with uncertainty

Sometimes the degree of “medical dangerousness” is difficult to quantify, in part because the diagnosis may be uncertain; or even when the diagnosis is known, prognostication may be difficult.10

In instances of uncertainty, considering the possibility that there may be a serious underlying condition is important both medically (in case immediate intervention can prevent a negative outcome) and ethically (to benefit the patient and preserve autonomy by preventing morbidity that may be impairing). Thus, shifting the standard for decisional capacity to require a higher level of understanding and appreciation may be justified.

In such cases, even though a patient has some level of decisional capacity, a surrogate may be needed. One approach might be to attempt shared decision-making between the patient and surrogate, although ultimate decision-making should be left to the surrogate.

Careful documentation is important

As with other medical issues, in cases of treatment refusal, thoroughly document the process, whether or not treatment refusal is ultimately honored. Note findings from the evaluation including decisional capacity and medical and psychiatric dangerousness, thinking associated with the assessment, and specific management plans.

Record any decision for involuntary hospitalization or treatment because of psychiatric dangerousness or the need for a surrogate decision-maker because of impaired decisional capacity. Finally, describe your reasons for a course of action in the special situations noted above.

Benefits of this model

This approach to treatment refusal is consistent and involves clear standards and processes for evaluation, regardless of setting, problem, type of patient, or practitioner. It facilitates respect for persons, equal treatment independent of diagnosis, and appropriate involvement of surrogate decision-makers and the courts.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this work have been presented at the following meetings:

Bekelman D, Carrese J (2003). Treatment refusal and decisional competence assessment. Concurrent Session, Clinical Ethics Consultation: First International Summit, Cleveland, Ohio.

Bekelman D (2002). Treatment refusal: Conceptual models and clinical approaches. Workshop, 49th annual meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, Tucson, Arizona.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Bekelman, MD, MPH, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, 4200 East 9th Avenue, B180, Denver, CO 80262. E-mail: [email protected]

- The process for evaluating treatment refusal should be consistent regardless of setting, problem (ie, medical or psychiatric), type of patient, or practitioner.

- Assess decisional capacity, psychiatric dangerousness, and medical risk in all cases of treatment refusal while addressing potential causes of treatment refusal.

- Based on these assessments, choose between: a) respecting the treatment refusal, b) obtaining a surrogate, or c) mandating hospitalization and possibly treatment.

An 80-year-old woman with diabetes who has been your patient for many years is in failing health and may need dialysis for deteriorating kidney function. She refuses even to consider further evaluation.

A 37-year-old man has, according to his family, become increasingly depressed and makes comments suggesting suicidal ideation. They are afraid for his safety. He says he’s just going through a rough period and doesn’t need help.

Would you be prepared to handle instances of treatment refusal such as these? Treatment refusal can be challenging, creating conflicts among patients, families, and health care providers, and raising important ethical considerations. A patient’s autonomy may be undermined if her wishes are overridden. Inappropriately confining, restraining, or treating patients may cause harm. Failing to obtain a surrogate when indicated may result in a missed opportunity to benefit a patient. Refusal of treatment, when unaddressed or mishandled, may lead to patient dissatisfaction, substandard care, increased litigation, or disparities in care.

Clearer guidelines are needed to help clinicians evaluate and manage patients who refuse treatment. Building on previous work in treatment refusal, informed consent, and competency theory, we propose an approach to treatment refusal that provides 3 unique contributions:

- First, our model integrates medical and psychiatric treatment refusal practices—usually found in separate literature bases—into one model.

- Second, it emphasizes that evaluations of both decisional capacity and dangerousness (both defined later) are crucial to determining the appropriate response to treatment refusal.

- Third, it provides concrete guidance for how to decide between 3 actions: 1) respect the treatment refusal, 2) obtain a surrogate, or 3) mandate hospitalization and possibly treatment.

How to assess and manage treatment refusal

Step 1: Evaluate both decisional capacity and dangerousness

Grisso and Appelbaum have described an empirically tested model of how to evaluate decisional capacity.1Decisional capacity refers to the ability to make a choice about treatment, and it is determined by the presence and extent of functional abilities, which are hierarchical, from the simplest to the most complex:

- Making a choice (“I’d like to have the cardiac catheterization”)

- Understanding relevant details, such as diagnosis, prognosis, the benefits and burdens of different treatment alternatives, and what will happen without treatment

- Appreciating that the relevant details apply to oneself and will mean something for one’s own future

- Rationally describing why a choice was made (such as explaining why one would prefer a particular set of risks, benefits, or burdens from one treatment alternative over another).

Many factors may interfere with these abilities and they should be assessed,1 but additional discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

Not all patients with mental illness have impaired decisional capacity. On the contrary, there is significant variability in the decisional capacity of people with serious mental illness.2 One instrument to evaluate decisional capacity for treatment decisions has been studied, but time constraints may limit its widespread application in clinical practice.3

Dangerousness in the clinical setting is generally defined as the intent to harm oneself or others, creating imminent risk. For the purposes of our model, this will be called “psychiatric dangerousness.” Other sources describe the assessment of psychiatric dangerousness in more detail,4 but the assessment typically includes a thorough psychosocial history, an evaluation for mental illness, a determination of risk factors for suicide, and often corroborating history from family or friends. “Medical dangerousness” is defined as the risk of morbidity or mortality that accompanies medical intervention or non-intervention.

In cases of treatment refusal, explicitly assess both decisional capacity and dangerousness. There are 3 benefits in doing so. First, it helps avoid the tendency to assess dangerousness only in the psychiatric context and decisional capacity in the general medical context. Second, it provides a useful way to approach treatment refusal when the cause of symptoms or complaints is ambiguous. Third, it helps when a patient exhibits both medical and psychiatric symptoms of illness.

Step 2: Determine the need for involuntary hospitalization and treatment

The ideal threshold for involuntary confinement is the point at which those who will harm themselves or others are confined and protected, while those who will not harm themselves or others are not. Determining the ideal threshold for involuntary treatment is difficult. Besides the challenges in predicting dangerousness,5 this determination involves a balance between potentially competing goals: respecting individual liberties, enhancing quality of life, and protecting patients and others from harm.

In general, there is greater justification for involuntary hospitalization with increasing “psychiatric dangerousness.” States vary on what requirements must be met for involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. Many jurisdictions have additional requirements to force psychiatric treatment; in some jurisdictions, forcing psychiatric treatment is not permitted.

Step 3: Determine the need for a surrogate decision-maker

The strength of the case for surrogate decision-making increases as decisional capacity decreases. A surrogate decision-maker is the person authorized to make decisions for a person who is not fully autonomous because of impaired decisional capacity. The ethical justification for obtaining a surrogate is to respect the patient’s prior ability to be informed and make a choice. Some patients share decision-making with other family or friends and this should be respected.

In our view, a surrogate should be obtained for a patient with impaired decisional capacity even when significant “psychiatric dangerousness” is present and involuntary hospitalization or treatment is pursued. The principle of equal respect for persons supports the view that since incompetent patients with medical problems are afforded a surrogate, so should incompetent patients with psychiatric problems.

Some might argue that the judge ordering the mandatory hospitalization or treatment is the surrogate. However, others who know the patient better and are more familiar with their values are more likely to provide authentic substituted judgment. At the same time, safety concerns for the patient (in the case of suicidal intent) or others (in the case of homicidal intent) require that surrogate decision-making be restricted. Surprisingly, no law or regulation in the US, to our knowledge, mandates appointing a surrogate for a patient who is involuntarily hospitalized or treated.

Managing treatment refusal in practice

Evaluating decisional capacity and dangerousness leads to 3 possible decisions: 1) respect the treatment refusal, 2) obtain a surrogate, or 3) mandate hospitalization and possibly treatment. FIGURES 1 AND 2 depict such decisions for psychiatric and medical dangerousness, respectively. The important question during evaluation is not, “Is there decisional capacity or dangerousness?” but is rather, “How much decisional capacity or dangerousness is present?” Even if different evaluators agree which decision-making abilities are present or how much psychiatric dangerousness exists, a value judgment must be made to decide the threshold at which a surrogate is obtained or the court is petitioned for involuntary hospitalization or treatment.

Similarities in the assessments of medical and psychiatric dangerousness.

When a patient exhibits adequate decisional capacity and insufficient dangerousness of either type, treatment refusal is respected. When decisional capacity is judged to be impaired, a surrogate should be obtained regardless of the type of dangerousness that is present.

FIGURE 1

Decisional capacity and psychiatric dangerousness

In assessing a patient’s decisional capacity and level of psychiatric dangerousness, we depart from traditional practice (lower right-hand box) and recommend obtaining a surrogate decision-maker when the patient has inadequate decisional capacity.

FIGURE 2

Decisional capacity and medical dangerousness

In assessing a patient’s decisional capacity and level of medical dangerousness, our model considers the clinical context in judging whether to override or respect a patient’s decision (lower left-hand box).

Decisional capacity

Differences in the assessments. Two boxes in the figures deserve comment. First, the bottom right box of FIGURE 1 recommends a departure from current practice. As described earlier, we recommend obtaining a surrogate for patients who have impaired decisional capacity and are involuntarily hospitalized for psychiatric dangerousness. Second, in the bottom left box of FIGURE 2, treatment refusal by a patient who has decisional capacity and “medical dangerousness” may be respected or overridden depending on contextual factors. The long history of respect for liberty, and the requirement not to invade another’s body without consent generally supports respecting treatment refusal.

When decisions may be overridden in a patient with adequate decisional capacity and medical dangerousness. During a public health emergency, such as a tuberculosis or SARS outbreak, ensuring the public’s safety may outweigh respect for individual liberties. When someone with tuberculosis refuses treatment and has adequate decisional capacity, legal precedent and ethical justification exist to defend involuntary confinement or treatment in certain circumstances.6

When the threshold for adequate decisional capacity changes based on the level of medical dangerousness. With increasing medical dangerousness, a given level of decisional capacity may be regarded as inadequate, and treatment refusal may be appropriately questioned and consideration given to naming a surrogate.7,8 Alternatively, when there is little “medical dangerousness,” less decisional capacity may be required for a treatment refusal to be respected. This approach is controversial because it involves a modifiable notion of decisional capacity.9

In addition, this approach is not appropriate in all contexts. For example, in patients who are imminently dying with irreversible terminal illness, “medical dangerousness” may be very high, but the threshold for adequate decisional capacity should not necessarily be very high.

Dealing with uncertainty

Sometimes the degree of “medical dangerousness” is difficult to quantify, in part because the diagnosis may be uncertain; or even when the diagnosis is known, prognostication may be difficult.10

In instances of uncertainty, considering the possibility that there may be a serious underlying condition is important both medically (in case immediate intervention can prevent a negative outcome) and ethically (to benefit the patient and preserve autonomy by preventing morbidity that may be impairing). Thus, shifting the standard for decisional capacity to require a higher level of understanding and appreciation may be justified.

In such cases, even though a patient has some level of decisional capacity, a surrogate may be needed. One approach might be to attempt shared decision-making between the patient and surrogate, although ultimate decision-making should be left to the surrogate.

Careful documentation is important

As with other medical issues, in cases of treatment refusal, thoroughly document the process, whether or not treatment refusal is ultimately honored. Note findings from the evaluation including decisional capacity and medical and psychiatric dangerousness, thinking associated with the assessment, and specific management plans.

Record any decision for involuntary hospitalization or treatment because of psychiatric dangerousness or the need for a surrogate decision-maker because of impaired decisional capacity. Finally, describe your reasons for a course of action in the special situations noted above.

Benefits of this model

This approach to treatment refusal is consistent and involves clear standards and processes for evaluation, regardless of setting, problem, type of patient, or practitioner. It facilitates respect for persons, equal treatment independent of diagnosis, and appropriate involvement of surrogate decision-makers and the courts.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this work have been presented at the following meetings:

Bekelman D, Carrese J (2003). Treatment refusal and decisional competence assessment. Concurrent Session, Clinical Ethics Consultation: First International Summit, Cleveland, Ohio.

Bekelman D (2002). Treatment refusal: Conceptual models and clinical approaches. Workshop, 49th annual meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, Tucson, Arizona.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Bekelman, MD, MPH, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, 4200 East 9th Avenue, B180, Denver, CO 80262. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

2. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. III: Abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law Hum Behav 1995;19:149-174.

3. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1415–1419. The tool itself can be found online at: www.prpress.com/books/mact-setfr.html.

4. Packman WL, Marlitt RE, Bongar B, O’Connor PT. A comprehensive and concise assessment of suicide risk. Behav Sci Law 2004;22:667.-

5. Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1994.

6. Gostin LO. Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

7. Buchanan AE, Brock DW. Deciding for Others: The Ethics of Surrogate Decision Making. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press,1989.

8. Roth LH, Meisel A, Lidz CW. Tests of competency to consent to treatment. Am J Psych 1977;134:279-284.

9. Beauchamp TL, Childress CF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

10. Christakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1999.

1. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

2. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. III: Abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law Hum Behav 1995;19:149-174.

3. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1415–1419. The tool itself can be found online at: www.prpress.com/books/mact-setfr.html.

4. Packman WL, Marlitt RE, Bongar B, O’Connor PT. A comprehensive and concise assessment of suicide risk. Behav Sci Law 2004;22:667.-

5. Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1994.

6. Gostin LO. Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

7. Buchanan AE, Brock DW. Deciding for Others: The Ethics of Surrogate Decision Making. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press,1989.

8. Roth LH, Meisel A, Lidz CW. Tests of competency to consent to treatment. Am J Psych 1977;134:279-284.

9. Beauchamp TL, Childress CF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

10. Christakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1999.