User login

Screening for and treating bacterial vaginosis is a routine part of preterm birth prevention. A quick course of antibiotics for women with proven infection is easy and inexpensive – and if it works, a bullet with a huge bang for the buck.

Unfortunately, it just doesn’t seem to work.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial presented Feb. 6 at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, found that clindamycin conferred no benefit on women with bacterial vaginosis (BV)who were at high risk for preterm birth.

The trial, held from May 2006 through June 2011, randomized 2,869 pregnant women at low risk for preterm birth to receive either one of two oral clindamycin regimens or placebo before 15 weeks’ gestation.

The study was complicated by the unexpectedly low preterm birth rate in the group that wasn’t treated, Dr. Gilles Brabant said at the meeting.

The study design assumed a 2% rate in the treated group and 4% rate in the nontreated group. The actual rate was extremely low and almost identical (1.2% in the treatment groups vs. 1% in the comparator group).

However, the power of calculation held in the final analysis, leading Dr. Brabant, of the University Hospital of Lille, France, to question just why the antibiotic wasn’t improving outcomes.

"We to have to ask ourselves, is BV the guilty party or might it be something else? We need to look further – to genetics, inflammatory response, and molecular biology – and perhaps even the microbiome."

Dr. Michal Elovitz said that she couldn’t agree more. In fact, during her presentation she said that it’s time to rethink the whole pathological paradigm of preterm birth.

The current concept starts with bacterial colonization that ascends to the cervix from the vagina, instigating an inflammatory response. The bacteria then propagate in the placenta, provoking another inflammatory response in the decidua and uterus. From there, they travel through the umbilical cord, getting the baby into the inflammation act.

"All of these serve to promote uterine contractions and degradation of the fetal membrane," said Dr. Elovitz of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. "In this model, contractions are the primary event leading to delivery – cervical remodeling is a secondary event."

But this model doesn’t explain why antibiotic trials fail to demonstrate any effect on preterm birth. In the face of these repeat failures, Dr. Elovitz said, "We need to ask if bacterial ascension into the uterus is a necessary pathogenesis for preterm birth."

She’s not letting bacteria off the hook, but she is suggesting that they may affect pregnancy outcomes in a much different way – through the collective influence of their communities at the cervicovaginal junction.

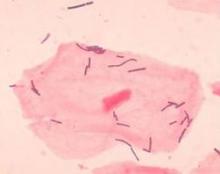

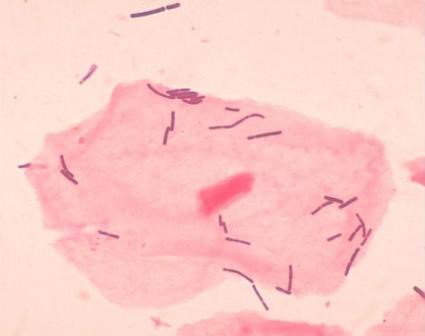

Dr. Elovitz’s research has identified four distinct communities that can populate the cervicovaginal space. Three of these are dominated by different species of lactobacilli – a species never before associated with preterm birth. The fourth lacks lactobacilli; it’s largely composed of the anaerobes that have typically been associated with BV.

She said she thinks it’s time for a new pathogenic model for preterm birth.

"We propose that the microbiota – specifically a dysbiotic community in the cervicovaginal space – may induce cervical remodeling through the interaction of the microbiota, the cervical-epithelial barrier, and the immune system," she said.

She investigated this by looking at 77 cervicovaginal samples*. Of these, 21 belonged to women who went on to have a preterm birth. The samples were obtained at 20-24 weeks and 24-28 weeks’ gestation, and genotyped to discover the exact nature of all their bacterial inhabitants. She found 168 phylotypes, and went on to focus on the 50 that were most frequently present in all samples.

The women who had term and preterm deliveries were demographically similar, except that in the first gestational period, cervical length was already significantly shorter in women destined for a preterm delivery – a hint that something was going on months before any symptoms developed.

It turns out that a single species of lactobacillus – L. iners – dominated the samples of almost all of the women who eventually had a preterm delivery. Women who had term pregnancies were significantly less likely to have that group. In fact, their samples were about evenly split between groups headed by L. crispatus and the Lactobacilli-absent anaerobes.

Lactobacilli generally aren’t thought of as bad guys, Dr. Elovitz said. But emerging data suggest that some strains aren’t so mild-mannered. "We know from nonpregnant data that there are different strains that are either pro- or negative immune mediators," which may play into the preterm birth puzzle.

"Lactobacillus also has mutations that can produce a much less favorable mucin, and if you have those mutations you are much more prone to acquire sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infections."

The good news is that while antibiotics may not be the key to this puzzle, the microbiome can be modified. For example, a plant-based diet has been found to change the microbiota associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

It’s not clear yet if, or how, the cervicovaginal communities could be modulated to protect against preterm birth. But it is clear that the well-trod path of antibiotics just isn’t getting the results researchers, doctors, mothers, and babies need.

Neither Dr. Brabant nor Dr. Elovitz had any financial declarations.

*Correction, 2/7/2014: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the number of cervicovaginal samples.

Screening for and treating bacterial vaginosis is a routine part of preterm birth prevention. A quick course of antibiotics for women with proven infection is easy and inexpensive – and if it works, a bullet with a huge bang for the buck.

Unfortunately, it just doesn’t seem to work.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial presented Feb. 6 at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, found that clindamycin conferred no benefit on women with bacterial vaginosis (BV)who were at high risk for preterm birth.

The trial, held from May 2006 through June 2011, randomized 2,869 pregnant women at low risk for preterm birth to receive either one of two oral clindamycin regimens or placebo before 15 weeks’ gestation.

The study was complicated by the unexpectedly low preterm birth rate in the group that wasn’t treated, Dr. Gilles Brabant said at the meeting.

The study design assumed a 2% rate in the treated group and 4% rate in the nontreated group. The actual rate was extremely low and almost identical (1.2% in the treatment groups vs. 1% in the comparator group).

However, the power of calculation held in the final analysis, leading Dr. Brabant, of the University Hospital of Lille, France, to question just why the antibiotic wasn’t improving outcomes.

"We to have to ask ourselves, is BV the guilty party or might it be something else? We need to look further – to genetics, inflammatory response, and molecular biology – and perhaps even the microbiome."

Dr. Michal Elovitz said that she couldn’t agree more. In fact, during her presentation she said that it’s time to rethink the whole pathological paradigm of preterm birth.

The current concept starts with bacterial colonization that ascends to the cervix from the vagina, instigating an inflammatory response. The bacteria then propagate in the placenta, provoking another inflammatory response in the decidua and uterus. From there, they travel through the umbilical cord, getting the baby into the inflammation act.

"All of these serve to promote uterine contractions and degradation of the fetal membrane," said Dr. Elovitz of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. "In this model, contractions are the primary event leading to delivery – cervical remodeling is a secondary event."

But this model doesn’t explain why antibiotic trials fail to demonstrate any effect on preterm birth. In the face of these repeat failures, Dr. Elovitz said, "We need to ask if bacterial ascension into the uterus is a necessary pathogenesis for preterm birth."

She’s not letting bacteria off the hook, but she is suggesting that they may affect pregnancy outcomes in a much different way – through the collective influence of their communities at the cervicovaginal junction.

Dr. Elovitz’s research has identified four distinct communities that can populate the cervicovaginal space. Three of these are dominated by different species of lactobacilli – a species never before associated with preterm birth. The fourth lacks lactobacilli; it’s largely composed of the anaerobes that have typically been associated with BV.

She said she thinks it’s time for a new pathogenic model for preterm birth.

"We propose that the microbiota – specifically a dysbiotic community in the cervicovaginal space – may induce cervical remodeling through the interaction of the microbiota, the cervical-epithelial barrier, and the immune system," she said.

She investigated this by looking at 77 cervicovaginal samples*. Of these, 21 belonged to women who went on to have a preterm birth. The samples were obtained at 20-24 weeks and 24-28 weeks’ gestation, and genotyped to discover the exact nature of all their bacterial inhabitants. She found 168 phylotypes, and went on to focus on the 50 that were most frequently present in all samples.

The women who had term and preterm deliveries were demographically similar, except that in the first gestational period, cervical length was already significantly shorter in women destined for a preterm delivery – a hint that something was going on months before any symptoms developed.

It turns out that a single species of lactobacillus – L. iners – dominated the samples of almost all of the women who eventually had a preterm delivery. Women who had term pregnancies were significantly less likely to have that group. In fact, their samples were about evenly split between groups headed by L. crispatus and the Lactobacilli-absent anaerobes.

Lactobacilli generally aren’t thought of as bad guys, Dr. Elovitz said. But emerging data suggest that some strains aren’t so mild-mannered. "We know from nonpregnant data that there are different strains that are either pro- or negative immune mediators," which may play into the preterm birth puzzle.

"Lactobacillus also has mutations that can produce a much less favorable mucin, and if you have those mutations you are much more prone to acquire sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infections."

The good news is that while antibiotics may not be the key to this puzzle, the microbiome can be modified. For example, a plant-based diet has been found to change the microbiota associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

It’s not clear yet if, or how, the cervicovaginal communities could be modulated to protect against preterm birth. But it is clear that the well-trod path of antibiotics just isn’t getting the results researchers, doctors, mothers, and babies need.

Neither Dr. Brabant nor Dr. Elovitz had any financial declarations.

*Correction, 2/7/2014: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the number of cervicovaginal samples.

Screening for and treating bacterial vaginosis is a routine part of preterm birth prevention. A quick course of antibiotics for women with proven infection is easy and inexpensive – and if it works, a bullet with a huge bang for the buck.

Unfortunately, it just doesn’t seem to work.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial presented Feb. 6 at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, found that clindamycin conferred no benefit on women with bacterial vaginosis (BV)who were at high risk for preterm birth.

The trial, held from May 2006 through June 2011, randomized 2,869 pregnant women at low risk for preterm birth to receive either one of two oral clindamycin regimens or placebo before 15 weeks’ gestation.

The study was complicated by the unexpectedly low preterm birth rate in the group that wasn’t treated, Dr. Gilles Brabant said at the meeting.

The study design assumed a 2% rate in the treated group and 4% rate in the nontreated group. The actual rate was extremely low and almost identical (1.2% in the treatment groups vs. 1% in the comparator group).

However, the power of calculation held in the final analysis, leading Dr. Brabant, of the University Hospital of Lille, France, to question just why the antibiotic wasn’t improving outcomes.

"We to have to ask ourselves, is BV the guilty party or might it be something else? We need to look further – to genetics, inflammatory response, and molecular biology – and perhaps even the microbiome."

Dr. Michal Elovitz said that she couldn’t agree more. In fact, during her presentation she said that it’s time to rethink the whole pathological paradigm of preterm birth.

The current concept starts with bacterial colonization that ascends to the cervix from the vagina, instigating an inflammatory response. The bacteria then propagate in the placenta, provoking another inflammatory response in the decidua and uterus. From there, they travel through the umbilical cord, getting the baby into the inflammation act.

"All of these serve to promote uterine contractions and degradation of the fetal membrane," said Dr. Elovitz of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. "In this model, contractions are the primary event leading to delivery – cervical remodeling is a secondary event."

But this model doesn’t explain why antibiotic trials fail to demonstrate any effect on preterm birth. In the face of these repeat failures, Dr. Elovitz said, "We need to ask if bacterial ascension into the uterus is a necessary pathogenesis for preterm birth."

She’s not letting bacteria off the hook, but she is suggesting that they may affect pregnancy outcomes in a much different way – through the collective influence of their communities at the cervicovaginal junction.

Dr. Elovitz’s research has identified four distinct communities that can populate the cervicovaginal space. Three of these are dominated by different species of lactobacilli – a species never before associated with preterm birth. The fourth lacks lactobacilli; it’s largely composed of the anaerobes that have typically been associated with BV.

She said she thinks it’s time for a new pathogenic model for preterm birth.

"We propose that the microbiota – specifically a dysbiotic community in the cervicovaginal space – may induce cervical remodeling through the interaction of the microbiota, the cervical-epithelial barrier, and the immune system," she said.

She investigated this by looking at 77 cervicovaginal samples*. Of these, 21 belonged to women who went on to have a preterm birth. The samples were obtained at 20-24 weeks and 24-28 weeks’ gestation, and genotyped to discover the exact nature of all their bacterial inhabitants. She found 168 phylotypes, and went on to focus on the 50 that were most frequently present in all samples.

The women who had term and preterm deliveries were demographically similar, except that in the first gestational period, cervical length was already significantly shorter in women destined for a preterm delivery – a hint that something was going on months before any symptoms developed.

It turns out that a single species of lactobacillus – L. iners – dominated the samples of almost all of the women who eventually had a preterm delivery. Women who had term pregnancies were significantly less likely to have that group. In fact, their samples were about evenly split between groups headed by L. crispatus and the Lactobacilli-absent anaerobes.

Lactobacilli generally aren’t thought of as bad guys, Dr. Elovitz said. But emerging data suggest that some strains aren’t so mild-mannered. "We know from nonpregnant data that there are different strains that are either pro- or negative immune mediators," which may play into the preterm birth puzzle.

"Lactobacillus also has mutations that can produce a much less favorable mucin, and if you have those mutations you are much more prone to acquire sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infections."

The good news is that while antibiotics may not be the key to this puzzle, the microbiome can be modified. For example, a plant-based diet has been found to change the microbiota associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

It’s not clear yet if, or how, the cervicovaginal communities could be modulated to protect against preterm birth. But it is clear that the well-trod path of antibiotics just isn’t getting the results researchers, doctors, mothers, and babies need.

Neither Dr. Brabant nor Dr. Elovitz had any financial declarations.

*Correction, 2/7/2014: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the number of cervicovaginal samples.