User login

- Consider the research showing that spiritual faith is an ally to health and positive health behaviors, and that many patients rely on their spiritual beliefs in times of illness (C).

- Regardless of personal ethic, physicians need a set of principles to guide decisions concerning the appropriateness of addressing spiritual issues when such issues arise in the clinical setting (C).

- The EBQT (Evidence-Belief-Quality Care-Time) paradigm provides a natural set of principles for consistent clinical decision-making regarding spiritual or alternative adjuncts to medical therapy (C).

In recent years, physicians have been encouraged to assess their patient’s spiritual sources of strength or stress when taking a medical history. However, the decision to act on such information can be ethically complex. Physicians may feel apprehensive about delving into spiritual issues in clinical practice without clear ethical guidelines as to which actions may, or may not, be taken in response to information gained from such an inquiry. This paper introduces the EBQT paradigm, a set of 4 principles designed to guide physicians who wish to address clinically relevant spiritual issues in their practice.

Need for guidelines

The contribution of a patient’s personal faith to the success or failure of medical care has long been a subject of interest to physicians. Sir William Osler, contrasting the beneficial and harmful effects of various expressions of faith, called it “an essential factor in the practice of medicine.”1 Research highlights both the beneficial aspects of a patient’s spiritual faith,2-7 and the harmful effects of religious struggle in regard to illness8 or lack of strength and comfort from religion.10

Due to the potential relevance of spiritual beliefs and practices, many authors9-13 recommend that physicians include a brief spiritual assessment when taking a patient’s medical history. A decision to act on such information, however, can prove ethically complex. Should physicians have a referral relationship with local clergy? Is it ethical to pray with patients who make such a request? Can a physician express support for faith-based activities? When is it appropriate to confront a patient’s harmful religious beliefs?

Some authors argue against addressing spiritual issues, calling the activity premature and ethically questionable.14 Others acknowledge a connection between spiritual faith and health, yet do not agree on the extent to which physicians should address spiritual issues.15 We elect not to discuss the details of each point of view here, but do emphasize that, despite holding divergent viewpoints, authors seem to agree that guidelines for behavior are lacking. Richard Sloan and colleagues conclude their critique by stating “between the extremes of rejecting the idea that religion and faith can bring comfort to some people coping with illness and endorsing the view that physicians should actively promote religious activity among patients lies a vast uncharted territory in which guidelines for appropriate behavior are needed urgently.”16

This paper introduces such guidelines in the form of what we call the EBQT Paradigm. With the principles of this paradigm, physicians may personally evaluate or openly debate the ethics of certain spiritual adjuncts to therapy using consistent parameters on which to base their conclusions. Previous authors have developed principles for accommodating the religious beliefs of patients.17 Others have provided recommendations for the discussion of spiritual issues with patients.18 However, guidelines for acting on a patient’s spiritual history were not found in a Medline search of the medical literature, including articles and letters from peer-reviewed publications from the last 15 years that refer to or assess the clinical relevance of spirituality, prayer, clergy, religion, or faith.

The EBQT paradigm for spiritual assessment

The EBQT paradigm (Table 1) involves 4 principles: Evidence, Belief, Quality Care, and Time. Used in concert with a spiritual assessment, these principles provide an ethical model with which physicians may evaluate the benefit or harm in addressing spiritual sources of strength or stress in the clinical setting.

TABLE 1

EBQT Paradigm: 4 principles for determining appropriateness of religious/spiritual prescriptive recommendations

| Evidence |

| Does sufficient evidence of good quality exist to recommend this spiritual adjunct to therapy for this patient? |

| Belief |

| Does sufficient congruence exist between the patient’s belief, the physician’s belief, and relevance of therapy? |

| Quality care |

| Will this recommendation improve the quality of care for this patient? |

| Time |

| Can this recommendation be made and implemented within the time constraints of the clinical encounter, respecting the time committed to other patients? |

Principle of evidence

Before considering a spiritual adjunct to therapy, evaluate the evidence that supports a therapeutic advantage to such action. Two questions must be answered: 1) does sufficient evidence exist to recommend the action, and 2) what is the quality of that evidence?

One might logically question whether evidence exists at all to support a physician addressing spiritual issues. Several authors have thoroughly reviewed the evidence for a connection between spiritual commitment and health outcomes.19-21 It is not our intent to repeat their effort here. However, in reviewing their findings, we were struck by the varying quality of evidence found in the medical literature. In some cases, spiritually related actions are supported by abundant evidence; other spiritual practices lack sufficient data for recommendation in the clinical setting. As empirical evidence accumulates, physicians will be increasingly able to discern the therapeutic benefit of certain faith-based practices. Evidence alone, however, does not establish an ethical imperative to address a patient’s spiritual or faith-based practices. The physician’s belief, medical and patient values, and available time must also be taken into account.

Principle of belief

Belief in a given therapy, by both the patient and the physician, is a major part of successful doctor-patient interactions. Researchers recognize that a caregiver’s belief or disbelief in a given therapy can significantly alter a patient’s response to treatment; otherwise there would be no need to double-blind studies.

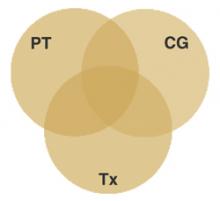

The principle of belief, illustrated in Figure 1, states a spiritual adjunct to therapy is maximally beneficial when congruence exists between the patient’s belief, the caregiver’s belief, and the relevance of that shared belief to therapy. Conversely, a spiritual adjunct to treatment is less appropriate when the principle of belief is violated by caregiver incongruence, patient incongruence, incongruence of therapy, or extreme incongruence of the caregiver, patient, and therapy.

FIGURE 1

Congruence of belief

Spiritual adjuncts to therapy are maximally beneficial when congruence exists between the patient’s belief (PT), the caregiver’s belief (CG), and the relevance of that shared belief to therapy (Tx).

A physician may respectfully observe and document the faith-based practices of a patient without supporting or criticizing these practices. Encouraging or integrating the patient’s faith-based practices into therapy, however, requires a personal judgment concerning how the patient’s beliefs and those of the caregiver are relevant to a medical condition. Even in cases of incongruence, using this model may lead to serendipitous therapeutic options as a caregiver and patient work together to find common ground for relevant recommendations.

Principle of quality care

The principle of quality care states that a patient’s spiritual beliefs are most appropriately incorporated into therapy when and if doing so improves the quality of care received by the patient.

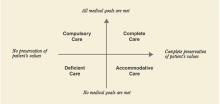

A popular definition characterizes quality care as the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes....”22 Many definitions of quality care share this narrow focus on health outcomes. However, patients may more broadly define quality of care by including the degree to which personal values are preserved. A comprehensive definition of quality care, illustrated in Figure 2, takes into account both desired health outcomes and the patient’s values.

Complete care occurs when medical goals are achieved and the patient’s values are preserved.

Accommodative care occurs when medical treatment is adjusted for the sake of a patient’s values, as when a patient declines vaccination or other therapies for religious reasons.

Compulsory care describes forced medical therapy without preservation of the patient’s values. This type of care may result from conflicts between religious beliefs and medical standards leading to a patient being treated against his or her will. The adverse effects of compulsory care can be minimized by a thorough patient history that includes questions concerning personal beliefs that may conflict with standard treatment.

Deficient care, defined as failure to achieve medical goals while also violating patient values, can result from poor medical management, patient non-adherence, or lack of communication.

During any clinical encounter, the caregiver’s ultimate goal should be to provide complete care. Accommodative care and compulsory care may be necessary at times, but deficient care should always be avoided.

FIGURE 2

Criteria for defining quality of care

Principle of time

Research underscores the commonly recognized relation between longer consultations and general satisfaction among patients.23,24 Yet time is too often a clinical luxury. Primary care physicians report lack of time as a barrier to providing a variety of potentially beneficial preventive services, including basic counsel on health issues,25-26 despite evidence that brief physician advice can lead to changes in a patient’s health behaviors.27 Similarly, family physicians28 report lack of time as the number one barrier to discussions of spiritual issues.

Generally, preventive health counseling in a primary care setting increases the length of time with a patient anywhere from 2.5 to 3.8 minutes.26,29 Time like this must be taken into account when weighing the importance of addressing spiritual issues with one patient against the time committed to other patients.

The principle of time states that addressing spiritual issues with patients who wish to do so is most appropriate when these issues can be entertained and any actions completed within the time constraints of clinical practice.

Lack of time should not be used routinely as an excuse to withhold care. Though spiritual matters, like other lifestyle issues, take time to address, the time invested may prove beneficial in the long run and management will require less time during follow up if core issues are addressed early and possibly incorporated into therapy.

The principle of time allows the caregiver to evaluate the feasibility of addressing clinically-relevant spiritual issues given a limited amount of time.

Applying the principles

Together, the principles of evidence, belief, quality care, and time serve as ethical precepts for guiding an appropriate response to information gained from a patient’s spiritual history. The scale shown in Table 2, and applied to the following cases, illustrates how these principles might be used in the clinical setting. The scale differentiates between appropriate, potential, and inappropriate recommendations according to the number of principles upheld by each recommendation. While admittedly pragmatic and far from comprehensive, this scale allows for the consistent clinical application of an otherwise theoretical model.

TABLE 2

Using the 4 EBQT principles to determine the usefulness of an action in the physician-patient encounter

| Number of EBQT principles upheld to treatment | Appropriateness of adjunct |

|---|---|

| All 4 | APPROPRIATE recommendation: potentially useful to physicians when a patient’s history warrants such action. Likely ethical. |

| 2 or 3 | POTENTIAL recommendation: action is limited to special circumstances and may not be useful to all physicians, even if warranted by the patient’s history. |

| 0 or 1 | INAPPROPRIATE recommendation: unlikely to be useful in the clinical physician-patient encounter. Risks being unethical. |

Case 1

A physician who maintains a relationship with local clergy is treating a 55-year-old woman with diabetes who has end-stage renal disease. The patient is distraught over lifestyle changes necessitated by dialysis. A spiritual assessment reveals the patient finds strength in her religious faith, actively participates in a local church, and speaks well of the pastoral staff.

Is referral to clergy an appropriate recommendation for addressing the patient’s social and personal issues?

Principle of evidence [+]: Evidence suggests a beneficial role for clergy in facilitating the use of in-home and community-based health services.30 Additionally, a chaplain or minister who knows the patient would be able to ensure she has access and transportation to congregational activities, such as worship or support groups. Religious involvement is associated with better disability outcomes31 and lower use of hospital services32 by medically ill older adults. In contrast, lack of religious participation33 and absence of strength and comfort in religion4 are associated with higher mortality.

Finally, clergy may help facilitate the use of private religious activities, such as prayer or devotional reading, which appear to promote lower blood pressure,34 survival advantage,3 and a reduction in cognitive symptoms of depression.35 The latter finding is particularly relevant to this patient whose intrinsic religious beliefs, according to research, statistically and independently predict a faster remission from depression related to the medical illness.36

Principle of belief [+]: Upheld by physician, patient, and therapy congruence. The physician maintains a referral relationship with local clergy, the patient expresses trust in her pastoral staff, and spiritual support from a trusted pastoral counselor, minister, or chaplain is relevant to the patient’s therapy.

Principle of quality care [+]: Referral promotes a more complete care, advancing medical goals, such as adherence to a renal treatment protocol, in a way that reinforces the patient’s values.

Principle of time [+]: The recommendation can actually save time in a busy practice, assuming an existing relationship with qualified local clergy.

The referral to clergy in this setting upholds all 4 principles and may be considered appropriate.

Case 2

A 25-year-old man with cystic fibrosis is admitted to a private religious hospital for an exacerbation of his illness. The patient’s spiritual history reveals a distant belief in a supreme being, but no formal faith or religious practice.

Can a religiously devout physician recommend religious attendance or devotional reading given this patient’s spiritual history?

Principle of evidence [–]: Some patients may rely on religious activities as a positive means of coping with chronic illness; however, no evidence suggests an advantage for beginning religious activities or attendance for mere health benefits.

Principle of belief [–]: The suggestion violates the principle of belief due to physician-patient incongruence.

Principle of quality care [–]: The recommendation does not acknowledge the patient’s values and would fail to advance medical goals, thereby increasing the risk of compulsory, or worse, deficient care.

Principle of time [+/–]: Whether the principle of time is violated depends on the amount of time allotted to make and implement such a recommendation.

Since only 1, if any, of the principles is upheld in this clinical scenario, the recommendation is considered inappropriate.

Even when faced with a scenario like this, the perceptive physician will gain insight into how a patient copes with illness by taking a spiritual history. Simply asking the question, “What do you rely on in times of illness?” may help identify adjuncts to therapy that will be useful and more appropriate in a patient’s care.

Benefits of the EBQT paradigm

The EBQT paradigm was designed to help health-care providers regardless of their personal belief. Physicians with divergent points of view may use the 4 principles to come to similar, if not identical, conclusions on whether support of a patient’s spiritual practices is warranted. And, as illustrated in case 2, the paradigm allows recognition of inappropriate spiritually-based recommendations.

The cases discussed relate to organized religious practices, because it is in this arena we find the most controversy over physicians’ involvement with patients’ spiritual beliefs. However, we recognize that patients may seek spiritual sources of strength outside organized religion. The 4 principles are also helpful when encountering less formal and less controversial practices of spirituality as found in art, music, relaxation techniques, support groups, gardening, writing, etc. Furthermore, the principles are beneficial for evaluating the appropriateness of certain forms of alternative medicine—acupuncture, hypnosis, homeopathic or naturopathic therapies—regardless of whether these therapies are spiritual in nature.

Of course, conscience trumps all other principles. Caregivers should not compromise their own values. Nor should a patient be put into a potentially compromising position concerning his or her spiritual beliefs. Providing optimum care while avoiding such conflicts requires discernment. We find the EBQT paradigm, used with a careful spiritual assessment, provides helpful guidance in this regard.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ken Mueller, PhD, clinical psychologist in Anchorage, AK, and Dan Stockstill, PhD, professor of Bible and Religion, Harding University, for their thoughtful contribution to the development of the EBQT paradigm and the formation of this article. Disclosure: Robert T. Lawrence has served as a Christian minister since 1989. He completed medical school at the University of Washington School of Medicine and is currently a resident at the Greenwood Family Practice Residency in Greenwood, SC.

Corresponding author

Robert T. Lawrence, MD, MEd., 110 Firethorn Rd, Greenwood, SC 29649. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Osler W. The faith that heals. BMJ 1910;June 18:1470-1472.

2. Matthews D, McCullough M, Larson D, Koenig H, Sawyers J, Milano M. Religious commitment and health status: a review of the research and implications for family medicine. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:118-124.

3. Helm H, Hays J, Flint E, Koenig H, Blazer D. Does private religious activity prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3,851 older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55:M400-M405.

4. Oxman T, Freeman D, Manheimer E. Lack of social participation or religious strength and comfort as risk factors for death after cardiac surgery in the elderly. Psychosom Med 1995;57:5-15.

5. Koenig H, Cohen H, George L, Hays J, Larson D, Blazer D. Attendance at religious services, interleukin-6, and other biological parameters of immune function in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med 1997;27:233-250.

6. Woods T, Antoni M, Ironson G, Kling D. Religiosity is associated with affective and immune status in symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. J Psychosom Res 1999;46:165-176.

7. Koenig H, George L, Meador K, Blazer D, Ford S. Religious practices and alcoholism in a southern adult population. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994;45:225-231.

8. Pargament K, Koenig H, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1881-1885.

9. Anandarajah G, Hight E. Spirituality and medical practice: using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician 2001;63:81-88.

10. Post S, Puchalski C, Larson D. Physicians and patient spirituality: professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:578-583.

11. Maugans T, Wadland W. Religion and family medicine: a survey of physicians and patients. J Fam Pract 1991;32:210-213.

12. Ehman J, Ott B, Short T, Ciampa R, Hansen-Flaschen J. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1803-1806.

13. Block S. Psychological considerations, growth, and transcendence at the end of life. JAMA 2001;285:2898-2905.

14. Sloan R, Bagiella E, VandeCreek L, et al. Should physicians prescribe religious activities? N Engl J Med 2000;342:1913-1916.

15. Koenig G, Idler E, Kasl S, et al. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: a rebuttal to skeptics. Int J Psychiatry Med 1999;29:123-131.

16. Sloan R, Bagiella E, Powell T. Religion, spirituality, and medicine. Lancet 1999;353:664-667.

17. Buryska J. Assessing the Ethical weight of cultural, religious and spiritual claims in the clinical context. J Med Ethics 2001;27:118-122.

18. Lo B, Ruston D, Kates L, Arnold R, Cohen C, Faber-Langendoen K, et al. Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life. a practical guide for physicians. JAMA 2002;287:749-754.

19. Matthews D, McCullough M, Larson D, Koenig H, Swyers J, Milano M. Religious commitment and health status: a review of the research and implications for family medicine. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:118-124.

20. Mueller P, Plevak D, Rummans T. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:1225-1235.

21. Levin J, Puchalski C. Religion and spirituality in medicine: research and education. JAMA 1997;278:792-793.

22. Blumenthal D. Quality of health care, part 1: quality of care—what is it? N Engl J Med 1996;335:891-894.

23. Shum C, Humphreys A, Wheeler D, Cochrane M, Skoda S, Clement S. Nurse management of patients with minor illnesses in general practice: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2000;320:1038-1043.

24. Venning P, Durie A, Roland M, Roberts C, Leese B. Randomised controlled trial comparing cost effectiveness of general practitioners and nurse practitioners in primary care. BMJ 2000;320:1048-1053.

25. Jaen C, Stange K, Nutting P. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract 1994;38:166-171.

26. Goodwin M, Flocke S, Borawski E, Zyzanski S, Stange K. Direct observation of health-habit counseling of adolescents. Arch Ped Ado Med 1999;153:367-373.

27. Fleming M, Manwell L, Barry K, Adams W, Stauffacher E. Brief physician advice for alcohol problems in older adults: a randomized community-based trial. J Fam Pract 1999;48:378-384.

28. Ellis M, Vinson D, Ewigman B. Addressing spiritual concerns of patients. J Fam Pract 1999;48:105-109.

29. Merenstein D, Green L, Fryer G, Dovey S. Shortchanging adolescents: room for improvement in preventive care by physicians. Fam Med 2001;33:120-123.

30. Schoenberg N, Campbell K, Johnson M. Physicians and clergy as facilitators of formal services for older adults. J Aging Soc Policy 1999;11(1):9-26.

31. Idler E, Kasl S. Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons ii: attendance at religious services as a predictor of the course of disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997;52:S306-S316.

32. Koenig H, Larson D. Use of hospital services, religious attendance, and religious affiliation. South Med J 1998;91:925-932.

33. Strawbridge W, Cohen R, Shema S, Kaplan G. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. Am J Pub Health 1997;87:957-968.

34. Koenig H, George L, Hays J, Larson D, Cohen H, Blazer D. The relationship between religious activities and blood pressure in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998;28:189-213.

35. Koenig H, Cohen H, Blazer D, Kudler H, Drishnan K, Sibert T. Religious coping and cognitive symptoms of depression in elderly medical patients. Psychosomatics 1995;36(4):369-375.

36. Koenig H, George L, Peterson B. Religiosity and remission of depression in medically ill older adults. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:536-542.

- Consider the research showing that spiritual faith is an ally to health and positive health behaviors, and that many patients rely on their spiritual beliefs in times of illness (C).

- Regardless of personal ethic, physicians need a set of principles to guide decisions concerning the appropriateness of addressing spiritual issues when such issues arise in the clinical setting (C).

- The EBQT (Evidence-Belief-Quality Care-Time) paradigm provides a natural set of principles for consistent clinical decision-making regarding spiritual or alternative adjuncts to medical therapy (C).

In recent years, physicians have been encouraged to assess their patient’s spiritual sources of strength or stress when taking a medical history. However, the decision to act on such information can be ethically complex. Physicians may feel apprehensive about delving into spiritual issues in clinical practice without clear ethical guidelines as to which actions may, or may not, be taken in response to information gained from such an inquiry. This paper introduces the EBQT paradigm, a set of 4 principles designed to guide physicians who wish to address clinically relevant spiritual issues in their practice.

Need for guidelines

The contribution of a patient’s personal faith to the success or failure of medical care has long been a subject of interest to physicians. Sir William Osler, contrasting the beneficial and harmful effects of various expressions of faith, called it “an essential factor in the practice of medicine.”1 Research highlights both the beneficial aspects of a patient’s spiritual faith,2-7 and the harmful effects of religious struggle in regard to illness8 or lack of strength and comfort from religion.10

Due to the potential relevance of spiritual beliefs and practices, many authors9-13 recommend that physicians include a brief spiritual assessment when taking a patient’s medical history. A decision to act on such information, however, can prove ethically complex. Should physicians have a referral relationship with local clergy? Is it ethical to pray with patients who make such a request? Can a physician express support for faith-based activities? When is it appropriate to confront a patient’s harmful religious beliefs?

Some authors argue against addressing spiritual issues, calling the activity premature and ethically questionable.14 Others acknowledge a connection between spiritual faith and health, yet do not agree on the extent to which physicians should address spiritual issues.15 We elect not to discuss the details of each point of view here, but do emphasize that, despite holding divergent viewpoints, authors seem to agree that guidelines for behavior are lacking. Richard Sloan and colleagues conclude their critique by stating “between the extremes of rejecting the idea that religion and faith can bring comfort to some people coping with illness and endorsing the view that physicians should actively promote religious activity among patients lies a vast uncharted territory in which guidelines for appropriate behavior are needed urgently.”16

This paper introduces such guidelines in the form of what we call the EBQT Paradigm. With the principles of this paradigm, physicians may personally evaluate or openly debate the ethics of certain spiritual adjuncts to therapy using consistent parameters on which to base their conclusions. Previous authors have developed principles for accommodating the religious beliefs of patients.17 Others have provided recommendations for the discussion of spiritual issues with patients.18 However, guidelines for acting on a patient’s spiritual history were not found in a Medline search of the medical literature, including articles and letters from peer-reviewed publications from the last 15 years that refer to or assess the clinical relevance of spirituality, prayer, clergy, religion, or faith.

The EBQT paradigm for spiritual assessment

The EBQT paradigm (Table 1) involves 4 principles: Evidence, Belief, Quality Care, and Time. Used in concert with a spiritual assessment, these principles provide an ethical model with which physicians may evaluate the benefit or harm in addressing spiritual sources of strength or stress in the clinical setting.

TABLE 1

EBQT Paradigm: 4 principles for determining appropriateness of religious/spiritual prescriptive recommendations

| Evidence |

| Does sufficient evidence of good quality exist to recommend this spiritual adjunct to therapy for this patient? |

| Belief |

| Does sufficient congruence exist between the patient’s belief, the physician’s belief, and relevance of therapy? |

| Quality care |

| Will this recommendation improve the quality of care for this patient? |

| Time |

| Can this recommendation be made and implemented within the time constraints of the clinical encounter, respecting the time committed to other patients? |

Principle of evidence

Before considering a spiritual adjunct to therapy, evaluate the evidence that supports a therapeutic advantage to such action. Two questions must be answered: 1) does sufficient evidence exist to recommend the action, and 2) what is the quality of that evidence?

One might logically question whether evidence exists at all to support a physician addressing spiritual issues. Several authors have thoroughly reviewed the evidence for a connection between spiritual commitment and health outcomes.19-21 It is not our intent to repeat their effort here. However, in reviewing their findings, we were struck by the varying quality of evidence found in the medical literature. In some cases, spiritually related actions are supported by abundant evidence; other spiritual practices lack sufficient data for recommendation in the clinical setting. As empirical evidence accumulates, physicians will be increasingly able to discern the therapeutic benefit of certain faith-based practices. Evidence alone, however, does not establish an ethical imperative to address a patient’s spiritual or faith-based practices. The physician’s belief, medical and patient values, and available time must also be taken into account.

Principle of belief

Belief in a given therapy, by both the patient and the physician, is a major part of successful doctor-patient interactions. Researchers recognize that a caregiver’s belief or disbelief in a given therapy can significantly alter a patient’s response to treatment; otherwise there would be no need to double-blind studies.

The principle of belief, illustrated in Figure 1, states a spiritual adjunct to therapy is maximally beneficial when congruence exists between the patient’s belief, the caregiver’s belief, and the relevance of that shared belief to therapy. Conversely, a spiritual adjunct to treatment is less appropriate when the principle of belief is violated by caregiver incongruence, patient incongruence, incongruence of therapy, or extreme incongruence of the caregiver, patient, and therapy.

FIGURE 1

Congruence of belief

Spiritual adjuncts to therapy are maximally beneficial when congruence exists between the patient’s belief (PT), the caregiver’s belief (CG), and the relevance of that shared belief to therapy (Tx).

A physician may respectfully observe and document the faith-based practices of a patient without supporting or criticizing these practices. Encouraging or integrating the patient’s faith-based practices into therapy, however, requires a personal judgment concerning how the patient’s beliefs and those of the caregiver are relevant to a medical condition. Even in cases of incongruence, using this model may lead to serendipitous therapeutic options as a caregiver and patient work together to find common ground for relevant recommendations.

Principle of quality care

The principle of quality care states that a patient’s spiritual beliefs are most appropriately incorporated into therapy when and if doing so improves the quality of care received by the patient.

A popular definition characterizes quality care as the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes....”22 Many definitions of quality care share this narrow focus on health outcomes. However, patients may more broadly define quality of care by including the degree to which personal values are preserved. A comprehensive definition of quality care, illustrated in Figure 2, takes into account both desired health outcomes and the patient’s values.

Complete care occurs when medical goals are achieved and the patient’s values are preserved.

Accommodative care occurs when medical treatment is adjusted for the sake of a patient’s values, as when a patient declines vaccination or other therapies for religious reasons.

Compulsory care describes forced medical therapy without preservation of the patient’s values. This type of care may result from conflicts between religious beliefs and medical standards leading to a patient being treated against his or her will. The adverse effects of compulsory care can be minimized by a thorough patient history that includes questions concerning personal beliefs that may conflict with standard treatment.

Deficient care, defined as failure to achieve medical goals while also violating patient values, can result from poor medical management, patient non-adherence, or lack of communication.

During any clinical encounter, the caregiver’s ultimate goal should be to provide complete care. Accommodative care and compulsory care may be necessary at times, but deficient care should always be avoided.

FIGURE 2

Criteria for defining quality of care

Principle of time

Research underscores the commonly recognized relation between longer consultations and general satisfaction among patients.23,24 Yet time is too often a clinical luxury. Primary care physicians report lack of time as a barrier to providing a variety of potentially beneficial preventive services, including basic counsel on health issues,25-26 despite evidence that brief physician advice can lead to changes in a patient’s health behaviors.27 Similarly, family physicians28 report lack of time as the number one barrier to discussions of spiritual issues.

Generally, preventive health counseling in a primary care setting increases the length of time with a patient anywhere from 2.5 to 3.8 minutes.26,29 Time like this must be taken into account when weighing the importance of addressing spiritual issues with one patient against the time committed to other patients.

The principle of time states that addressing spiritual issues with patients who wish to do so is most appropriate when these issues can be entertained and any actions completed within the time constraints of clinical practice.

Lack of time should not be used routinely as an excuse to withhold care. Though spiritual matters, like other lifestyle issues, take time to address, the time invested may prove beneficial in the long run and management will require less time during follow up if core issues are addressed early and possibly incorporated into therapy.

The principle of time allows the caregiver to evaluate the feasibility of addressing clinically-relevant spiritual issues given a limited amount of time.

Applying the principles

Together, the principles of evidence, belief, quality care, and time serve as ethical precepts for guiding an appropriate response to information gained from a patient’s spiritual history. The scale shown in Table 2, and applied to the following cases, illustrates how these principles might be used in the clinical setting. The scale differentiates between appropriate, potential, and inappropriate recommendations according to the number of principles upheld by each recommendation. While admittedly pragmatic and far from comprehensive, this scale allows for the consistent clinical application of an otherwise theoretical model.

TABLE 2

Using the 4 EBQT principles to determine the usefulness of an action in the physician-patient encounter

| Number of EBQT principles upheld to treatment | Appropriateness of adjunct |

|---|---|

| All 4 | APPROPRIATE recommendation: potentially useful to physicians when a patient’s history warrants such action. Likely ethical. |

| 2 or 3 | POTENTIAL recommendation: action is limited to special circumstances and may not be useful to all physicians, even if warranted by the patient’s history. |

| 0 or 1 | INAPPROPRIATE recommendation: unlikely to be useful in the clinical physician-patient encounter. Risks being unethical. |

Case 1

A physician who maintains a relationship with local clergy is treating a 55-year-old woman with diabetes who has end-stage renal disease. The patient is distraught over lifestyle changes necessitated by dialysis. A spiritual assessment reveals the patient finds strength in her religious faith, actively participates in a local church, and speaks well of the pastoral staff.

Is referral to clergy an appropriate recommendation for addressing the patient’s social and personal issues?

Principle of evidence [+]: Evidence suggests a beneficial role for clergy in facilitating the use of in-home and community-based health services.30 Additionally, a chaplain or minister who knows the patient would be able to ensure she has access and transportation to congregational activities, such as worship or support groups. Religious involvement is associated with better disability outcomes31 and lower use of hospital services32 by medically ill older adults. In contrast, lack of religious participation33 and absence of strength and comfort in religion4 are associated with higher mortality.

Finally, clergy may help facilitate the use of private religious activities, such as prayer or devotional reading, which appear to promote lower blood pressure,34 survival advantage,3 and a reduction in cognitive symptoms of depression.35 The latter finding is particularly relevant to this patient whose intrinsic religious beliefs, according to research, statistically and independently predict a faster remission from depression related to the medical illness.36

Principle of belief [+]: Upheld by physician, patient, and therapy congruence. The physician maintains a referral relationship with local clergy, the patient expresses trust in her pastoral staff, and spiritual support from a trusted pastoral counselor, minister, or chaplain is relevant to the patient’s therapy.

Principle of quality care [+]: Referral promotes a more complete care, advancing medical goals, such as adherence to a renal treatment protocol, in a way that reinforces the patient’s values.

Principle of time [+]: The recommendation can actually save time in a busy practice, assuming an existing relationship with qualified local clergy.

The referral to clergy in this setting upholds all 4 principles and may be considered appropriate.

Case 2

A 25-year-old man with cystic fibrosis is admitted to a private religious hospital for an exacerbation of his illness. The patient’s spiritual history reveals a distant belief in a supreme being, but no formal faith or religious practice.

Can a religiously devout physician recommend religious attendance or devotional reading given this patient’s spiritual history?

Principle of evidence [–]: Some patients may rely on religious activities as a positive means of coping with chronic illness; however, no evidence suggests an advantage for beginning religious activities or attendance for mere health benefits.

Principle of belief [–]: The suggestion violates the principle of belief due to physician-patient incongruence.

Principle of quality care [–]: The recommendation does not acknowledge the patient’s values and would fail to advance medical goals, thereby increasing the risk of compulsory, or worse, deficient care.

Principle of time [+/–]: Whether the principle of time is violated depends on the amount of time allotted to make and implement such a recommendation.

Since only 1, if any, of the principles is upheld in this clinical scenario, the recommendation is considered inappropriate.

Even when faced with a scenario like this, the perceptive physician will gain insight into how a patient copes with illness by taking a spiritual history. Simply asking the question, “What do you rely on in times of illness?” may help identify adjuncts to therapy that will be useful and more appropriate in a patient’s care.

Benefits of the EBQT paradigm

The EBQT paradigm was designed to help health-care providers regardless of their personal belief. Physicians with divergent points of view may use the 4 principles to come to similar, if not identical, conclusions on whether support of a patient’s spiritual practices is warranted. And, as illustrated in case 2, the paradigm allows recognition of inappropriate spiritually-based recommendations.

The cases discussed relate to organized religious practices, because it is in this arena we find the most controversy over physicians’ involvement with patients’ spiritual beliefs. However, we recognize that patients may seek spiritual sources of strength outside organized religion. The 4 principles are also helpful when encountering less formal and less controversial practices of spirituality as found in art, music, relaxation techniques, support groups, gardening, writing, etc. Furthermore, the principles are beneficial for evaluating the appropriateness of certain forms of alternative medicine—acupuncture, hypnosis, homeopathic or naturopathic therapies—regardless of whether these therapies are spiritual in nature.

Of course, conscience trumps all other principles. Caregivers should not compromise their own values. Nor should a patient be put into a potentially compromising position concerning his or her spiritual beliefs. Providing optimum care while avoiding such conflicts requires discernment. We find the EBQT paradigm, used with a careful spiritual assessment, provides helpful guidance in this regard.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ken Mueller, PhD, clinical psychologist in Anchorage, AK, and Dan Stockstill, PhD, professor of Bible and Religion, Harding University, for their thoughtful contribution to the development of the EBQT paradigm and the formation of this article. Disclosure: Robert T. Lawrence has served as a Christian minister since 1989. He completed medical school at the University of Washington School of Medicine and is currently a resident at the Greenwood Family Practice Residency in Greenwood, SC.

Corresponding author

Robert T. Lawrence, MD, MEd., 110 Firethorn Rd, Greenwood, SC 29649. E-mail: [email protected].

- Consider the research showing that spiritual faith is an ally to health and positive health behaviors, and that many patients rely on their spiritual beliefs in times of illness (C).

- Regardless of personal ethic, physicians need a set of principles to guide decisions concerning the appropriateness of addressing spiritual issues when such issues arise in the clinical setting (C).

- The EBQT (Evidence-Belief-Quality Care-Time) paradigm provides a natural set of principles for consistent clinical decision-making regarding spiritual or alternative adjuncts to medical therapy (C).

In recent years, physicians have been encouraged to assess their patient’s spiritual sources of strength or stress when taking a medical history. However, the decision to act on such information can be ethically complex. Physicians may feel apprehensive about delving into spiritual issues in clinical practice without clear ethical guidelines as to which actions may, or may not, be taken in response to information gained from such an inquiry. This paper introduces the EBQT paradigm, a set of 4 principles designed to guide physicians who wish to address clinically relevant spiritual issues in their practice.

Need for guidelines

The contribution of a patient’s personal faith to the success or failure of medical care has long been a subject of interest to physicians. Sir William Osler, contrasting the beneficial and harmful effects of various expressions of faith, called it “an essential factor in the practice of medicine.”1 Research highlights both the beneficial aspects of a patient’s spiritual faith,2-7 and the harmful effects of religious struggle in regard to illness8 or lack of strength and comfort from religion.10

Due to the potential relevance of spiritual beliefs and practices, many authors9-13 recommend that physicians include a brief spiritual assessment when taking a patient’s medical history. A decision to act on such information, however, can prove ethically complex. Should physicians have a referral relationship with local clergy? Is it ethical to pray with patients who make such a request? Can a physician express support for faith-based activities? When is it appropriate to confront a patient’s harmful religious beliefs?

Some authors argue against addressing spiritual issues, calling the activity premature and ethically questionable.14 Others acknowledge a connection between spiritual faith and health, yet do not agree on the extent to which physicians should address spiritual issues.15 We elect not to discuss the details of each point of view here, but do emphasize that, despite holding divergent viewpoints, authors seem to agree that guidelines for behavior are lacking. Richard Sloan and colleagues conclude their critique by stating “between the extremes of rejecting the idea that religion and faith can bring comfort to some people coping with illness and endorsing the view that physicians should actively promote religious activity among patients lies a vast uncharted territory in which guidelines for appropriate behavior are needed urgently.”16

This paper introduces such guidelines in the form of what we call the EBQT Paradigm. With the principles of this paradigm, physicians may personally evaluate or openly debate the ethics of certain spiritual adjuncts to therapy using consistent parameters on which to base their conclusions. Previous authors have developed principles for accommodating the religious beliefs of patients.17 Others have provided recommendations for the discussion of spiritual issues with patients.18 However, guidelines for acting on a patient’s spiritual history were not found in a Medline search of the medical literature, including articles and letters from peer-reviewed publications from the last 15 years that refer to or assess the clinical relevance of spirituality, prayer, clergy, religion, or faith.

The EBQT paradigm for spiritual assessment

The EBQT paradigm (Table 1) involves 4 principles: Evidence, Belief, Quality Care, and Time. Used in concert with a spiritual assessment, these principles provide an ethical model with which physicians may evaluate the benefit or harm in addressing spiritual sources of strength or stress in the clinical setting.

TABLE 1

EBQT Paradigm: 4 principles for determining appropriateness of religious/spiritual prescriptive recommendations

| Evidence |

| Does sufficient evidence of good quality exist to recommend this spiritual adjunct to therapy for this patient? |

| Belief |

| Does sufficient congruence exist between the patient’s belief, the physician’s belief, and relevance of therapy? |

| Quality care |

| Will this recommendation improve the quality of care for this patient? |

| Time |

| Can this recommendation be made and implemented within the time constraints of the clinical encounter, respecting the time committed to other patients? |

Principle of evidence

Before considering a spiritual adjunct to therapy, evaluate the evidence that supports a therapeutic advantage to such action. Two questions must be answered: 1) does sufficient evidence exist to recommend the action, and 2) what is the quality of that evidence?

One might logically question whether evidence exists at all to support a physician addressing spiritual issues. Several authors have thoroughly reviewed the evidence for a connection between spiritual commitment and health outcomes.19-21 It is not our intent to repeat their effort here. However, in reviewing their findings, we were struck by the varying quality of evidence found in the medical literature. In some cases, spiritually related actions are supported by abundant evidence; other spiritual practices lack sufficient data for recommendation in the clinical setting. As empirical evidence accumulates, physicians will be increasingly able to discern the therapeutic benefit of certain faith-based practices. Evidence alone, however, does not establish an ethical imperative to address a patient’s spiritual or faith-based practices. The physician’s belief, medical and patient values, and available time must also be taken into account.

Principle of belief

Belief in a given therapy, by both the patient and the physician, is a major part of successful doctor-patient interactions. Researchers recognize that a caregiver’s belief or disbelief in a given therapy can significantly alter a patient’s response to treatment; otherwise there would be no need to double-blind studies.

The principle of belief, illustrated in Figure 1, states a spiritual adjunct to therapy is maximally beneficial when congruence exists between the patient’s belief, the caregiver’s belief, and the relevance of that shared belief to therapy. Conversely, a spiritual adjunct to treatment is less appropriate when the principle of belief is violated by caregiver incongruence, patient incongruence, incongruence of therapy, or extreme incongruence of the caregiver, patient, and therapy.

FIGURE 1

Congruence of belief

Spiritual adjuncts to therapy are maximally beneficial when congruence exists between the patient’s belief (PT), the caregiver’s belief (CG), and the relevance of that shared belief to therapy (Tx).

A physician may respectfully observe and document the faith-based practices of a patient without supporting or criticizing these practices. Encouraging or integrating the patient’s faith-based practices into therapy, however, requires a personal judgment concerning how the patient’s beliefs and those of the caregiver are relevant to a medical condition. Even in cases of incongruence, using this model may lead to serendipitous therapeutic options as a caregiver and patient work together to find common ground for relevant recommendations.

Principle of quality care

The principle of quality care states that a patient’s spiritual beliefs are most appropriately incorporated into therapy when and if doing so improves the quality of care received by the patient.

A popular definition characterizes quality care as the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes....”22 Many definitions of quality care share this narrow focus on health outcomes. However, patients may more broadly define quality of care by including the degree to which personal values are preserved. A comprehensive definition of quality care, illustrated in Figure 2, takes into account both desired health outcomes and the patient’s values.

Complete care occurs when medical goals are achieved and the patient’s values are preserved.

Accommodative care occurs when medical treatment is adjusted for the sake of a patient’s values, as when a patient declines vaccination or other therapies for religious reasons.

Compulsory care describes forced medical therapy without preservation of the patient’s values. This type of care may result from conflicts between religious beliefs and medical standards leading to a patient being treated against his or her will. The adverse effects of compulsory care can be minimized by a thorough patient history that includes questions concerning personal beliefs that may conflict with standard treatment.

Deficient care, defined as failure to achieve medical goals while also violating patient values, can result from poor medical management, patient non-adherence, or lack of communication.

During any clinical encounter, the caregiver’s ultimate goal should be to provide complete care. Accommodative care and compulsory care may be necessary at times, but deficient care should always be avoided.

FIGURE 2

Criteria for defining quality of care

Principle of time

Research underscores the commonly recognized relation between longer consultations and general satisfaction among patients.23,24 Yet time is too often a clinical luxury. Primary care physicians report lack of time as a barrier to providing a variety of potentially beneficial preventive services, including basic counsel on health issues,25-26 despite evidence that brief physician advice can lead to changes in a patient’s health behaviors.27 Similarly, family physicians28 report lack of time as the number one barrier to discussions of spiritual issues.

Generally, preventive health counseling in a primary care setting increases the length of time with a patient anywhere from 2.5 to 3.8 minutes.26,29 Time like this must be taken into account when weighing the importance of addressing spiritual issues with one patient against the time committed to other patients.

The principle of time states that addressing spiritual issues with patients who wish to do so is most appropriate when these issues can be entertained and any actions completed within the time constraints of clinical practice.

Lack of time should not be used routinely as an excuse to withhold care. Though spiritual matters, like other lifestyle issues, take time to address, the time invested may prove beneficial in the long run and management will require less time during follow up if core issues are addressed early and possibly incorporated into therapy.

The principle of time allows the caregiver to evaluate the feasibility of addressing clinically-relevant spiritual issues given a limited amount of time.

Applying the principles

Together, the principles of evidence, belief, quality care, and time serve as ethical precepts for guiding an appropriate response to information gained from a patient’s spiritual history. The scale shown in Table 2, and applied to the following cases, illustrates how these principles might be used in the clinical setting. The scale differentiates between appropriate, potential, and inappropriate recommendations according to the number of principles upheld by each recommendation. While admittedly pragmatic and far from comprehensive, this scale allows for the consistent clinical application of an otherwise theoretical model.

TABLE 2

Using the 4 EBQT principles to determine the usefulness of an action in the physician-patient encounter

| Number of EBQT principles upheld to treatment | Appropriateness of adjunct |

|---|---|

| All 4 | APPROPRIATE recommendation: potentially useful to physicians when a patient’s history warrants such action. Likely ethical. |

| 2 or 3 | POTENTIAL recommendation: action is limited to special circumstances and may not be useful to all physicians, even if warranted by the patient’s history. |

| 0 or 1 | INAPPROPRIATE recommendation: unlikely to be useful in the clinical physician-patient encounter. Risks being unethical. |

Case 1

A physician who maintains a relationship with local clergy is treating a 55-year-old woman with diabetes who has end-stage renal disease. The patient is distraught over lifestyle changes necessitated by dialysis. A spiritual assessment reveals the patient finds strength in her religious faith, actively participates in a local church, and speaks well of the pastoral staff.

Is referral to clergy an appropriate recommendation for addressing the patient’s social and personal issues?

Principle of evidence [+]: Evidence suggests a beneficial role for clergy in facilitating the use of in-home and community-based health services.30 Additionally, a chaplain or minister who knows the patient would be able to ensure she has access and transportation to congregational activities, such as worship or support groups. Religious involvement is associated with better disability outcomes31 and lower use of hospital services32 by medically ill older adults. In contrast, lack of religious participation33 and absence of strength and comfort in religion4 are associated with higher mortality.

Finally, clergy may help facilitate the use of private religious activities, such as prayer or devotional reading, which appear to promote lower blood pressure,34 survival advantage,3 and a reduction in cognitive symptoms of depression.35 The latter finding is particularly relevant to this patient whose intrinsic religious beliefs, according to research, statistically and independently predict a faster remission from depression related to the medical illness.36

Principle of belief [+]: Upheld by physician, patient, and therapy congruence. The physician maintains a referral relationship with local clergy, the patient expresses trust in her pastoral staff, and spiritual support from a trusted pastoral counselor, minister, or chaplain is relevant to the patient’s therapy.

Principle of quality care [+]: Referral promotes a more complete care, advancing medical goals, such as adherence to a renal treatment protocol, in a way that reinforces the patient’s values.

Principle of time [+]: The recommendation can actually save time in a busy practice, assuming an existing relationship with qualified local clergy.

The referral to clergy in this setting upholds all 4 principles and may be considered appropriate.

Case 2

A 25-year-old man with cystic fibrosis is admitted to a private religious hospital for an exacerbation of his illness. The patient’s spiritual history reveals a distant belief in a supreme being, but no formal faith or religious practice.

Can a religiously devout physician recommend religious attendance or devotional reading given this patient’s spiritual history?

Principle of evidence [–]: Some patients may rely on religious activities as a positive means of coping with chronic illness; however, no evidence suggests an advantage for beginning religious activities or attendance for mere health benefits.

Principle of belief [–]: The suggestion violates the principle of belief due to physician-patient incongruence.

Principle of quality care [–]: The recommendation does not acknowledge the patient’s values and would fail to advance medical goals, thereby increasing the risk of compulsory, or worse, deficient care.

Principle of time [+/–]: Whether the principle of time is violated depends on the amount of time allotted to make and implement such a recommendation.

Since only 1, if any, of the principles is upheld in this clinical scenario, the recommendation is considered inappropriate.

Even when faced with a scenario like this, the perceptive physician will gain insight into how a patient copes with illness by taking a spiritual history. Simply asking the question, “What do you rely on in times of illness?” may help identify adjuncts to therapy that will be useful and more appropriate in a patient’s care.

Benefits of the EBQT paradigm

The EBQT paradigm was designed to help health-care providers regardless of their personal belief. Physicians with divergent points of view may use the 4 principles to come to similar, if not identical, conclusions on whether support of a patient’s spiritual practices is warranted. And, as illustrated in case 2, the paradigm allows recognition of inappropriate spiritually-based recommendations.

The cases discussed relate to organized religious practices, because it is in this arena we find the most controversy over physicians’ involvement with patients’ spiritual beliefs. However, we recognize that patients may seek spiritual sources of strength outside organized religion. The 4 principles are also helpful when encountering less formal and less controversial practices of spirituality as found in art, music, relaxation techniques, support groups, gardening, writing, etc. Furthermore, the principles are beneficial for evaluating the appropriateness of certain forms of alternative medicine—acupuncture, hypnosis, homeopathic or naturopathic therapies—regardless of whether these therapies are spiritual in nature.

Of course, conscience trumps all other principles. Caregivers should not compromise their own values. Nor should a patient be put into a potentially compromising position concerning his or her spiritual beliefs. Providing optimum care while avoiding such conflicts requires discernment. We find the EBQT paradigm, used with a careful spiritual assessment, provides helpful guidance in this regard.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ken Mueller, PhD, clinical psychologist in Anchorage, AK, and Dan Stockstill, PhD, professor of Bible and Religion, Harding University, for their thoughtful contribution to the development of the EBQT paradigm and the formation of this article. Disclosure: Robert T. Lawrence has served as a Christian minister since 1989. He completed medical school at the University of Washington School of Medicine and is currently a resident at the Greenwood Family Practice Residency in Greenwood, SC.

Corresponding author

Robert T. Lawrence, MD, MEd., 110 Firethorn Rd, Greenwood, SC 29649. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Osler W. The faith that heals. BMJ 1910;June 18:1470-1472.

2. Matthews D, McCullough M, Larson D, Koenig H, Sawyers J, Milano M. Religious commitment and health status: a review of the research and implications for family medicine. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:118-124.

3. Helm H, Hays J, Flint E, Koenig H, Blazer D. Does private religious activity prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3,851 older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55:M400-M405.

4. Oxman T, Freeman D, Manheimer E. Lack of social participation or religious strength and comfort as risk factors for death after cardiac surgery in the elderly. Psychosom Med 1995;57:5-15.

5. Koenig H, Cohen H, George L, Hays J, Larson D, Blazer D. Attendance at religious services, interleukin-6, and other biological parameters of immune function in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med 1997;27:233-250.

6. Woods T, Antoni M, Ironson G, Kling D. Religiosity is associated with affective and immune status in symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. J Psychosom Res 1999;46:165-176.

7. Koenig H, George L, Meador K, Blazer D, Ford S. Religious practices and alcoholism in a southern adult population. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994;45:225-231.

8. Pargament K, Koenig H, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1881-1885.

9. Anandarajah G, Hight E. Spirituality and medical practice: using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician 2001;63:81-88.

10. Post S, Puchalski C, Larson D. Physicians and patient spirituality: professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:578-583.

11. Maugans T, Wadland W. Religion and family medicine: a survey of physicians and patients. J Fam Pract 1991;32:210-213.

12. Ehman J, Ott B, Short T, Ciampa R, Hansen-Flaschen J. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1803-1806.

13. Block S. Psychological considerations, growth, and transcendence at the end of life. JAMA 2001;285:2898-2905.

14. Sloan R, Bagiella E, VandeCreek L, et al. Should physicians prescribe religious activities? N Engl J Med 2000;342:1913-1916.

15. Koenig G, Idler E, Kasl S, et al. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: a rebuttal to skeptics. Int J Psychiatry Med 1999;29:123-131.

16. Sloan R, Bagiella E, Powell T. Religion, spirituality, and medicine. Lancet 1999;353:664-667.

17. Buryska J. Assessing the Ethical weight of cultural, religious and spiritual claims in the clinical context. J Med Ethics 2001;27:118-122.

18. Lo B, Ruston D, Kates L, Arnold R, Cohen C, Faber-Langendoen K, et al. Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life. a practical guide for physicians. JAMA 2002;287:749-754.

19. Matthews D, McCullough M, Larson D, Koenig H, Swyers J, Milano M. Religious commitment and health status: a review of the research and implications for family medicine. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:118-124.

20. Mueller P, Plevak D, Rummans T. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:1225-1235.

21. Levin J, Puchalski C. Religion and spirituality in medicine: research and education. JAMA 1997;278:792-793.

22. Blumenthal D. Quality of health care, part 1: quality of care—what is it? N Engl J Med 1996;335:891-894.

23. Shum C, Humphreys A, Wheeler D, Cochrane M, Skoda S, Clement S. Nurse management of patients with minor illnesses in general practice: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2000;320:1038-1043.

24. Venning P, Durie A, Roland M, Roberts C, Leese B. Randomised controlled trial comparing cost effectiveness of general practitioners and nurse practitioners in primary care. BMJ 2000;320:1048-1053.

25. Jaen C, Stange K, Nutting P. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract 1994;38:166-171.

26. Goodwin M, Flocke S, Borawski E, Zyzanski S, Stange K. Direct observation of health-habit counseling of adolescents. Arch Ped Ado Med 1999;153:367-373.

27. Fleming M, Manwell L, Barry K, Adams W, Stauffacher E. Brief physician advice for alcohol problems in older adults: a randomized community-based trial. J Fam Pract 1999;48:378-384.

28. Ellis M, Vinson D, Ewigman B. Addressing spiritual concerns of patients. J Fam Pract 1999;48:105-109.

29. Merenstein D, Green L, Fryer G, Dovey S. Shortchanging adolescents: room for improvement in preventive care by physicians. Fam Med 2001;33:120-123.

30. Schoenberg N, Campbell K, Johnson M. Physicians and clergy as facilitators of formal services for older adults. J Aging Soc Policy 1999;11(1):9-26.

31. Idler E, Kasl S. Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons ii: attendance at religious services as a predictor of the course of disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997;52:S306-S316.

32. Koenig H, Larson D. Use of hospital services, religious attendance, and religious affiliation. South Med J 1998;91:925-932.

33. Strawbridge W, Cohen R, Shema S, Kaplan G. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. Am J Pub Health 1997;87:957-968.

34. Koenig H, George L, Hays J, Larson D, Cohen H, Blazer D. The relationship between religious activities and blood pressure in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998;28:189-213.

35. Koenig H, Cohen H, Blazer D, Kudler H, Drishnan K, Sibert T. Religious coping and cognitive symptoms of depression in elderly medical patients. Psychosomatics 1995;36(4):369-375.

36. Koenig H, George L, Peterson B. Religiosity and remission of depression in medically ill older adults. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:536-542.

1. Osler W. The faith that heals. BMJ 1910;June 18:1470-1472.

2. Matthews D, McCullough M, Larson D, Koenig H, Sawyers J, Milano M. Religious commitment and health status: a review of the research and implications for family medicine. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:118-124.

3. Helm H, Hays J, Flint E, Koenig H, Blazer D. Does private religious activity prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3,851 older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55:M400-M405.

4. Oxman T, Freeman D, Manheimer E. Lack of social participation or religious strength and comfort as risk factors for death after cardiac surgery in the elderly. Psychosom Med 1995;57:5-15.

5. Koenig H, Cohen H, George L, Hays J, Larson D, Blazer D. Attendance at religious services, interleukin-6, and other biological parameters of immune function in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med 1997;27:233-250.

6. Woods T, Antoni M, Ironson G, Kling D. Religiosity is associated with affective and immune status in symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. J Psychosom Res 1999;46:165-176.

7. Koenig H, George L, Meador K, Blazer D, Ford S. Religious practices and alcoholism in a southern adult population. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994;45:225-231.

8. Pargament K, Koenig H, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1881-1885.

9. Anandarajah G, Hight E. Spirituality and medical practice: using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician 2001;63:81-88.

10. Post S, Puchalski C, Larson D. Physicians and patient spirituality: professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:578-583.

11. Maugans T, Wadland W. Religion and family medicine: a survey of physicians and patients. J Fam Pract 1991;32:210-213.

12. Ehman J, Ott B, Short T, Ciampa R, Hansen-Flaschen J. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1803-1806.

13. Block S. Psychological considerations, growth, and transcendence at the end of life. JAMA 2001;285:2898-2905.

14. Sloan R, Bagiella E, VandeCreek L, et al. Should physicians prescribe religious activities? N Engl J Med 2000;342:1913-1916.

15. Koenig G, Idler E, Kasl S, et al. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: a rebuttal to skeptics. Int J Psychiatry Med 1999;29:123-131.

16. Sloan R, Bagiella E, Powell T. Religion, spirituality, and medicine. Lancet 1999;353:664-667.

17. Buryska J. Assessing the Ethical weight of cultural, religious and spiritual claims in the clinical context. J Med Ethics 2001;27:118-122.

18. Lo B, Ruston D, Kates L, Arnold R, Cohen C, Faber-Langendoen K, et al. Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life. a practical guide for physicians. JAMA 2002;287:749-754.

19. Matthews D, McCullough M, Larson D, Koenig H, Swyers J, Milano M. Religious commitment and health status: a review of the research and implications for family medicine. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:118-124.

20. Mueller P, Plevak D, Rummans T. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:1225-1235.

21. Levin J, Puchalski C. Religion and spirituality in medicine: research and education. JAMA 1997;278:792-793.

22. Blumenthal D. Quality of health care, part 1: quality of care—what is it? N Engl J Med 1996;335:891-894.

23. Shum C, Humphreys A, Wheeler D, Cochrane M, Skoda S, Clement S. Nurse management of patients with minor illnesses in general practice: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2000;320:1038-1043.

24. Venning P, Durie A, Roland M, Roberts C, Leese B. Randomised controlled trial comparing cost effectiveness of general practitioners and nurse practitioners in primary care. BMJ 2000;320:1048-1053.

25. Jaen C, Stange K, Nutting P. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract 1994;38:166-171.

26. Goodwin M, Flocke S, Borawski E, Zyzanski S, Stange K. Direct observation of health-habit counseling of adolescents. Arch Ped Ado Med 1999;153:367-373.

27. Fleming M, Manwell L, Barry K, Adams W, Stauffacher E. Brief physician advice for alcohol problems in older adults: a randomized community-based trial. J Fam Pract 1999;48:378-384.

28. Ellis M, Vinson D, Ewigman B. Addressing spiritual concerns of patients. J Fam Pract 1999;48:105-109.

29. Merenstein D, Green L, Fryer G, Dovey S. Shortchanging adolescents: room for improvement in preventive care by physicians. Fam Med 2001;33:120-123.

30. Schoenberg N, Campbell K, Johnson M. Physicians and clergy as facilitators of formal services for older adults. J Aging Soc Policy 1999;11(1):9-26.

31. Idler E, Kasl S. Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons ii: attendance at religious services as a predictor of the course of disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997;52:S306-S316.

32. Koenig H, Larson D. Use of hospital services, religious attendance, and religious affiliation. South Med J 1998;91:925-932.

33. Strawbridge W, Cohen R, Shema S, Kaplan G. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. Am J Pub Health 1997;87:957-968.

34. Koenig H, George L, Hays J, Larson D, Cohen H, Blazer D. The relationship between religious activities and blood pressure in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998;28:189-213.

35. Koenig H, Cohen H, Blazer D, Kudler H, Drishnan K, Sibert T. Religious coping and cognitive symptoms of depression in elderly medical patients. Psychosomatics 1995;36(4):369-375.

36. Koenig H, George L, Peterson B. Religiosity and remission of depression in medically ill older adults. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:536-542.