User login

As I was reading my departmental, end-of-the-academic-year newsletter, I was pondering my own group’s hospitalist pipeline. Each year, I earnestly read the list of internal-medicine-program graduates, focusing on what and where they are going to practice. I first selfishly scan the list for “hospital medicine, MUSC.” Then I go back and reread the list to see who I can now send my discharges to or who I can refer any new friends or relatives who move to town, scanning the list for “primary care, MUSC.”

This year, similar to recent years, the list for “primary care” is slim.

SHM has long been motivated to think about the pipeline, about how to get the best and the brightest interested in practicing HM, and practicing primary care, as they are vital partners in the spectrum of generalist care. We need to know and understand our pipeline: Where will they train, how will they be trained, will they be prepared to function and thrive in the medical industry of tomorrow? Regardless of how or where you practice, all of us should be thinking about our pipeline.

As such, all of us should be thinking about graduate medical education (GME), how it is funded, how much it is funded, and what regulations control the types of specialties that come out of U.S. training programs.1 This is especially true given the projected need for more hospitalists in all areas of the hospital of the future, the ever-expanding role of “specialty hospitalists,” and the need for hospitalists during the “peri-hospital” stay (from pre-operative clinics to post-discharge clinics). And this is especially true given the ongoing projected expanse of the primary-care shortage.

The career path for physicians starts long before medical school and is heavily shaped by what types of physicians they are exposed to, when they are exposed to them, and what their experience was. The periods of medical school and graduate medical education training can have a profound impact on the “health” of the U.S. health-care system and whether it is equipped to care for the needs of its citizens.

American taxpayers have long been in the business of funding the physician pipeline. The federal government invests $13 billion annually on graduate medical education subsidies. The money flows directly to teaching hospitals to pay for the salaries of the trainees and the salaries of the attendings who supervise their work, as well as the hospital overhead that has to be invested to house these trainees during their tenure.

Federal subsidies for apprenticeships are relatively unheard of in other industries; this funding stream was initiated with the passage of Medicare almost 50 years ago, under the provision that additional training for medical students would result in better and safer medical care for all Americans. However, what was not set up as a tagline to these federal subsidies was any type of accountability on process or outcome measures, such as how exactly do teaching hospitals invest their GME money, and how will they produce the types and amounts of physicians that the U.S. needs?

Cold, Hard Facts

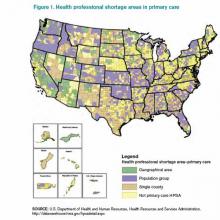

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, Health Resources and Services Administration, http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/hpsadetail.aspx

So what do Americans get for that annual $13 billion investment? We get what we should expect out of the “free will” of graduating residents: We get an oversupply of specialists in areas of abundance and an undersupply of generalists in most areas. The system “produces” the most appealing specialties (those handsomely reimbursed and highly prestigious), leaving a dwindling number of generalists to be spread thinly. And the most prestigious and top-ranked academic medical centers are the least likely to produce generalists. In many of these highly ranked training programs, less than 10% of their graduates go on to work in primary care, and even fewer work in rural or public health facilities. More than 20% of all residency programs produce no primary-care physicians (PCPs) at all. Despite the $13 billion annual investment, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) predicts a shortage of 45,000 primary-care physicians by 2020.2

Because of this shortage, even fully insured Americans find the act of securing a generalist to be problematic: Almost 1 in 5 of us live in a federally designated primary-care-shortage area (see Figure 1).3 It is estimated that our current training programs will produce 40% fewer PCPs than will be needed to keep pace with the baby boomers and the insurance expansion of the Affordable Care Act. Attempts at using GME subsidies as a lever to increase the number of generalists have failed for decades. Almost 30 years ago, Dan Quayle petitioned Medicare to forgo any subsidies to training programs that did not commit to graduating at least 70% of trainees to primary-care careers, to no avail. Years later, the Institute of Medicine appealed to the federal government to reduce the training of specialists, and increase the training pool for generalists, to no avail. To reduce the financial burden of GME training, about 15 years ago, Congress threw in place a stop-gap measure, putting a freeze on the total number of residency slots that would be funded, but it did not put any measures in place to ensure that the allocation of slots would match what the U.S. health-care system needs. This has left us in a global shortage of physicians, the most grotesque of which is among generalists in regions of greatest need.

The Good News

So where does this leave hospitalists? Fortunately for our specialty, hospital medicine remains very appealing to new graduates and to the health-care system. For new graduates, it offers a competitive salary and work-life balance, without additional fellowship training. For the health-care system, we are generalists who can enhance the “value equation,” having proven to enhance quality while simultaneously reducing cost. As generalists, our specialty remains relatively undifferentiated and flexible to meet the needs of the system, including caring for patients at many stages of an acute or chronic illness; pre-operative care; post-discharge transitions of care; and assisting in some stages of “specialty care” (e.g. the medical care of the neurologic emergency, the pregnant patient, comanagement with a variety of surgical subspecialists).

As a progressive specialty, we should continue to focus on the pipeline, not only to ensure we recruit our “favorite picks” to hospital medicine, but also to support the reform needed to enhance the appeal of generalist practices and reduce the irresistible appeal of specialty care. In this way, we can add yet another meaningful contribution to meeting the needs of the U.S. health-care system.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Longman P. First teach no harm. The Washington Monthly website. Available at: http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/july_august_2013/features/first_teach_no_harm045361.php?page=all. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician shortages to worsen without increases in residency training. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/150612/data/md-shortage.pdf. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

As I was reading my departmental, end-of-the-academic-year newsletter, I was pondering my own group’s hospitalist pipeline. Each year, I earnestly read the list of internal-medicine-program graduates, focusing on what and where they are going to practice. I first selfishly scan the list for “hospital medicine, MUSC.” Then I go back and reread the list to see who I can now send my discharges to or who I can refer any new friends or relatives who move to town, scanning the list for “primary care, MUSC.”

This year, similar to recent years, the list for “primary care” is slim.

SHM has long been motivated to think about the pipeline, about how to get the best and the brightest interested in practicing HM, and practicing primary care, as they are vital partners in the spectrum of generalist care. We need to know and understand our pipeline: Where will they train, how will they be trained, will they be prepared to function and thrive in the medical industry of tomorrow? Regardless of how or where you practice, all of us should be thinking about our pipeline.

As such, all of us should be thinking about graduate medical education (GME), how it is funded, how much it is funded, and what regulations control the types of specialties that come out of U.S. training programs.1 This is especially true given the projected need for more hospitalists in all areas of the hospital of the future, the ever-expanding role of “specialty hospitalists,” and the need for hospitalists during the “peri-hospital” stay (from pre-operative clinics to post-discharge clinics). And this is especially true given the ongoing projected expanse of the primary-care shortage.

The career path for physicians starts long before medical school and is heavily shaped by what types of physicians they are exposed to, when they are exposed to them, and what their experience was. The periods of medical school and graduate medical education training can have a profound impact on the “health” of the U.S. health-care system and whether it is equipped to care for the needs of its citizens.

American taxpayers have long been in the business of funding the physician pipeline. The federal government invests $13 billion annually on graduate medical education subsidies. The money flows directly to teaching hospitals to pay for the salaries of the trainees and the salaries of the attendings who supervise their work, as well as the hospital overhead that has to be invested to house these trainees during their tenure.

Federal subsidies for apprenticeships are relatively unheard of in other industries; this funding stream was initiated with the passage of Medicare almost 50 years ago, under the provision that additional training for medical students would result in better and safer medical care for all Americans. However, what was not set up as a tagline to these federal subsidies was any type of accountability on process or outcome measures, such as how exactly do teaching hospitals invest their GME money, and how will they produce the types and amounts of physicians that the U.S. needs?

Cold, Hard Facts

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, Health Resources and Services Administration, http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/hpsadetail.aspx

So what do Americans get for that annual $13 billion investment? We get what we should expect out of the “free will” of graduating residents: We get an oversupply of specialists in areas of abundance and an undersupply of generalists in most areas. The system “produces” the most appealing specialties (those handsomely reimbursed and highly prestigious), leaving a dwindling number of generalists to be spread thinly. And the most prestigious and top-ranked academic medical centers are the least likely to produce generalists. In many of these highly ranked training programs, less than 10% of their graduates go on to work in primary care, and even fewer work in rural or public health facilities. More than 20% of all residency programs produce no primary-care physicians (PCPs) at all. Despite the $13 billion annual investment, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) predicts a shortage of 45,000 primary-care physicians by 2020.2

Because of this shortage, even fully insured Americans find the act of securing a generalist to be problematic: Almost 1 in 5 of us live in a federally designated primary-care-shortage area (see Figure 1).3 It is estimated that our current training programs will produce 40% fewer PCPs than will be needed to keep pace with the baby boomers and the insurance expansion of the Affordable Care Act. Attempts at using GME subsidies as a lever to increase the number of generalists have failed for decades. Almost 30 years ago, Dan Quayle petitioned Medicare to forgo any subsidies to training programs that did not commit to graduating at least 70% of trainees to primary-care careers, to no avail. Years later, the Institute of Medicine appealed to the federal government to reduce the training of specialists, and increase the training pool for generalists, to no avail. To reduce the financial burden of GME training, about 15 years ago, Congress threw in place a stop-gap measure, putting a freeze on the total number of residency slots that would be funded, but it did not put any measures in place to ensure that the allocation of slots would match what the U.S. health-care system needs. This has left us in a global shortage of physicians, the most grotesque of which is among generalists in regions of greatest need.

The Good News

So where does this leave hospitalists? Fortunately for our specialty, hospital medicine remains very appealing to new graduates and to the health-care system. For new graduates, it offers a competitive salary and work-life balance, without additional fellowship training. For the health-care system, we are generalists who can enhance the “value equation,” having proven to enhance quality while simultaneously reducing cost. As generalists, our specialty remains relatively undifferentiated and flexible to meet the needs of the system, including caring for patients at many stages of an acute or chronic illness; pre-operative care; post-discharge transitions of care; and assisting in some stages of “specialty care” (e.g. the medical care of the neurologic emergency, the pregnant patient, comanagement with a variety of surgical subspecialists).

As a progressive specialty, we should continue to focus on the pipeline, not only to ensure we recruit our “favorite picks” to hospital medicine, but also to support the reform needed to enhance the appeal of generalist practices and reduce the irresistible appeal of specialty care. In this way, we can add yet another meaningful contribution to meeting the needs of the U.S. health-care system.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Longman P. First teach no harm. The Washington Monthly website. Available at: http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/july_august_2013/features/first_teach_no_harm045361.php?page=all. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician shortages to worsen without increases in residency training. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/150612/data/md-shortage.pdf. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

As I was reading my departmental, end-of-the-academic-year newsletter, I was pondering my own group’s hospitalist pipeline. Each year, I earnestly read the list of internal-medicine-program graduates, focusing on what and where they are going to practice. I first selfishly scan the list for “hospital medicine, MUSC.” Then I go back and reread the list to see who I can now send my discharges to or who I can refer any new friends or relatives who move to town, scanning the list for “primary care, MUSC.”

This year, similar to recent years, the list for “primary care” is slim.

SHM has long been motivated to think about the pipeline, about how to get the best and the brightest interested in practicing HM, and practicing primary care, as they are vital partners in the spectrum of generalist care. We need to know and understand our pipeline: Where will they train, how will they be trained, will they be prepared to function and thrive in the medical industry of tomorrow? Regardless of how or where you practice, all of us should be thinking about our pipeline.

As such, all of us should be thinking about graduate medical education (GME), how it is funded, how much it is funded, and what regulations control the types of specialties that come out of U.S. training programs.1 This is especially true given the projected need for more hospitalists in all areas of the hospital of the future, the ever-expanding role of “specialty hospitalists,” and the need for hospitalists during the “peri-hospital” stay (from pre-operative clinics to post-discharge clinics). And this is especially true given the ongoing projected expanse of the primary-care shortage.

The career path for physicians starts long before medical school and is heavily shaped by what types of physicians they are exposed to, when they are exposed to them, and what their experience was. The periods of medical school and graduate medical education training can have a profound impact on the “health” of the U.S. health-care system and whether it is equipped to care for the needs of its citizens.

American taxpayers have long been in the business of funding the physician pipeline. The federal government invests $13 billion annually on graduate medical education subsidies. The money flows directly to teaching hospitals to pay for the salaries of the trainees and the salaries of the attendings who supervise their work, as well as the hospital overhead that has to be invested to house these trainees during their tenure.

Federal subsidies for apprenticeships are relatively unheard of in other industries; this funding stream was initiated with the passage of Medicare almost 50 years ago, under the provision that additional training for medical students would result in better and safer medical care for all Americans. However, what was not set up as a tagline to these federal subsidies was any type of accountability on process or outcome measures, such as how exactly do teaching hospitals invest their GME money, and how will they produce the types and amounts of physicians that the U.S. needs?

Cold, Hard Facts

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, Health Resources and Services Administration, http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/hpsadetail.aspx

So what do Americans get for that annual $13 billion investment? We get what we should expect out of the “free will” of graduating residents: We get an oversupply of specialists in areas of abundance and an undersupply of generalists in most areas. The system “produces” the most appealing specialties (those handsomely reimbursed and highly prestigious), leaving a dwindling number of generalists to be spread thinly. And the most prestigious and top-ranked academic medical centers are the least likely to produce generalists. In many of these highly ranked training programs, less than 10% of their graduates go on to work in primary care, and even fewer work in rural or public health facilities. More than 20% of all residency programs produce no primary-care physicians (PCPs) at all. Despite the $13 billion annual investment, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) predicts a shortage of 45,000 primary-care physicians by 2020.2

Because of this shortage, even fully insured Americans find the act of securing a generalist to be problematic: Almost 1 in 5 of us live in a federally designated primary-care-shortage area (see Figure 1).3 It is estimated that our current training programs will produce 40% fewer PCPs than will be needed to keep pace with the baby boomers and the insurance expansion of the Affordable Care Act. Attempts at using GME subsidies as a lever to increase the number of generalists have failed for decades. Almost 30 years ago, Dan Quayle petitioned Medicare to forgo any subsidies to training programs that did not commit to graduating at least 70% of trainees to primary-care careers, to no avail. Years later, the Institute of Medicine appealed to the federal government to reduce the training of specialists, and increase the training pool for generalists, to no avail. To reduce the financial burden of GME training, about 15 years ago, Congress threw in place a stop-gap measure, putting a freeze on the total number of residency slots that would be funded, but it did not put any measures in place to ensure that the allocation of slots would match what the U.S. health-care system needs. This has left us in a global shortage of physicians, the most grotesque of which is among generalists in regions of greatest need.

The Good News

So where does this leave hospitalists? Fortunately for our specialty, hospital medicine remains very appealing to new graduates and to the health-care system. For new graduates, it offers a competitive salary and work-life balance, without additional fellowship training. For the health-care system, we are generalists who can enhance the “value equation,” having proven to enhance quality while simultaneously reducing cost. As generalists, our specialty remains relatively undifferentiated and flexible to meet the needs of the system, including caring for patients at many stages of an acute or chronic illness; pre-operative care; post-discharge transitions of care; and assisting in some stages of “specialty care” (e.g. the medical care of the neurologic emergency, the pregnant patient, comanagement with a variety of surgical subspecialists).

As a progressive specialty, we should continue to focus on the pipeline, not only to ensure we recruit our “favorite picks” to hospital medicine, but also to support the reform needed to enhance the appeal of generalist practices and reduce the irresistible appeal of specialty care. In this way, we can add yet another meaningful contribution to meeting the needs of the U.S. health-care system.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Longman P. First teach no harm. The Washington Monthly website. Available at: http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/july_august_2013/features/first_teach_no_harm045361.php?page=all. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician shortages to worsen without increases in residency training. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/150612/data/md-shortage.pdf. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.