User login

Public speaking is one of the best ways to market and promote your skills as a physician. It is an ethical way of communicating and showcasing your areas of interest and expertise to professional or lay audiences. Most physicians and health care professionals take pride in their ability to communicate. After all, that is how we take a history, discuss our findings with patients, and educate individuals on restoring or maintaining their health. Public speaking, though, for the most part is a learned skill. Except for presentations to faculty at bedside or at grand rounds, we have received little training in public speaking.

Few of us are naturally comfortable in front of a live audience or a TV or video camera. But with a little practice and diligent preparation, we can become good or even excellent, confident public speakers. This article—the first in a series of 3—provides you with preparatory tips and techniques to enhance your public speaking skills.

First, know your audience

Whether you are presenting to a group of 20 or 200, you can do certain things in advance to ensure that your presentation achieves the desired response. Most important: Know your audience. Don’t assume the audience is like you. To connect with them, you need to understand why your topic is important to them. What do they expect to learn from the presentation? Each attendee will be asking, “What’s in it for me?”

To keep listeners interested and engaged, you also must know their level of knowledge about the topic. If you are speaking to a group of residents about pelvic organ prolapse, you would use different language and content than if you were speaking to practicing primary care doctors; and these elements would be different again if you were speaking to a group of practicing urogynecologists. It’s insulting to recite basic information to highly knowledgeable physicians, or to present sophisticated technical content and complicated slides to novice physicians or lay people.

When presenting in a foreign country, learn how the culture of the audience differs from yours. How do they dress? What style of humor do they favor? How do they typically communicate? What gestures are appropriate or inappropriate? Are there religious influences to consider?

Practical steps. Before the meeting or event, speak to the organizer or meeting planner and find out the audience’s level of knowledge on the topic. Ask about audience expectations as well as demographics (such as age and background). If you are speaking at an industry event, research the event’s website and familiarize yourself with the mission of the event and who are the typical attendees. If you are presenting to a corporation, learn as much as you can about it by visiting its website, reading news reports, and reviewing associated blogs.

In addition to knowing the needs of the audience, ask the meeting planner about the goals and objectives for the program to make certain you can deliver on the requests.

Know your talk stem to stern

Review your slide material thoroughly. Understand each slide in the presentation and be comfortable with its content.

Avoid reading from slides. Reciting content that viewers can read for themselves breeds boredom and makes them lose interest. Further, when you are looking at the slides, you are not making eye contact with the audience and risk losing their attention. Good speakers are so comfortable with their slides that they can discuss each one without having to look at it.

Rehearse. The best way to achieve the foregoing is to rehearse. Your audience will be able to tell if you took the slide deck directly from a CD and loaded it into a computer and are giving the talk for the first time. You’ll need to know how long the program is to last and how long you are to speak. We suggest you practice with a timer to be certain you do not exceed the allotted time. Rehearse your talk aloud several times with all the props and audiovisual equipment you plan to use. This practice will help to curb filler words such as “ah” and “um.” It is also helpful to practice slide transitions, pauses, and even your breathing.

Prepare for the unexpected, too. Dinner meetings, for instance, may not start on time due to office or hospital delays for attending physicians, possibly resulting in a need to shorten your presentation.

Ask about the meeting agenda. If a meal is to be served, will you be speaking beforehand? This is the least favorable time slot, as you are holding people hostage before they can eat. Our preference is to speak after the appetizer is served and the orders have been taken by the wait staff. This way, attendees are not starving and they have something to drink. You can assure the waiters they won’t be disturbing you, and you can ask them to avoid walking in front of the projector. Ideally, you should end your presentation before dessert arrives and use the remaining time to field questions.

We suggest that you prepare a handout to be distributed at the end of the program, not before. You want your audience focused on you and your slides as you are speaking. Tell the audience you will be providing a handout of your presentation, which will minimize note-taking during your talk.

Your speech opening

The first and last 30 seconds of any speech probably have the most impact.1 Give extra thought, time, and effort to your opening and closing remarks. Do not open with “Good evening, it is a pleasure to be here tonight.” That wastes precious seconds.

While opening a speech with a joke or funny story is the conventional wisdom, ask yourself1:

- Is my selection appropriate to the occasion and for this audience?

- Is it in good taste?

- Does it relate to me (my service) or to the event or the group? Does it support my topic or its key points?

A humorous story or inspirational vignette that relates to your topic or audience can grab the audience’s attention. If you feel that demands more presentation skill than you possess at the outset of your public-speaking career, give the audience what you know and what they most want to hear. You know the questions that you have heard most at cocktail receptions or professional society meetings. So, put the answers to those questions in your speech.

For example. A scientist working with a major corporation was preparing a speech for a lay audience. Since most of the audience did not know what scientists do, he offered the following analogy: “Being a scientist is like doing a jigsaw puzzle in a snowstorm at night...you don’t have all the pieces...and you don’t have the picture on the front of the box to work from.” You can say more with less.1

Your closing

The closing is an important aspect of your speech. Summarize the key elements to your presentation. If you are going to take questions, a good approach is to say, “Before my closing remarks, are there any questions?” Following the questions, finish with a takeaway message that ties into your theme.1

Prepare an autobiographical introduction

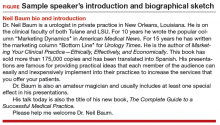

We suggest that you write your own introduction and e-mail it to the person who will be introducing you. Let them know it is a suggestion that they are welcome to modify. We have found that most emcees or meeting planners are delighted to have the introduction and will use it just as you have written it. Also bring hard copy with you; many emcees will have forgotten to download what you sent. The figure shows an example of the introduction that one of us (NHB) uses, and you are welcome to modify it for your own use.

Ask about and confirm audiovisual support

Ask the meeting planner ahead of time if they will be providing the computer, projector, and screen. And if, for instance, they will provide a projector but not a computer, make sure the computer you will bring is compatible with their projector. Also, you will probably not require a microphone for a small group, but if you are speaking in a loud restaurant, a portable microphone-speaker system may be helpful.

Arrive early at the program venue to make sure the computers, projector, screen placement, and seating arrangement are all in order. Nothing can sidetrack a speaker (even a seasoned one) like a problem with the computer or equipment setup—for example, your flash drive requiring a USB port cannot connect to the sponsor’s computer, or your program created on a Mac does not run on the sponsor’s PC.

Show time: Getting ready

Another benefit in arriving early, besides being able to check on the equipment, is the chance to greet the audience members as they enter. It is easier to speak to a group of friends than strangers. And if you can remember their names, you can call on them and ask their opinion or how they might manage a patient who has the condition you are discussing. You also could suggest to the meeting planner that name tags for attendees would be helpful.

Warming up. A public speaker, like an athlete, needs to warm up physically before the event. If the facility has an anteroom available, use it for the following exercises suggested by public speaking coach Patricia Fripp1:

- Stand on one leg and shake the other (remove high heels first). When you place your raised foot back on the floor, it will feel lighter than the other one. Repeat the exercise using the other leg. Imagine your energy going down through the floor and up out of your head. While this sounds quite comical, it is not. It is a practical technique used by actors.

- Shake your hands vigorously. Hold them above your head, bending your wrists and elbows, then return your arms to your sides. This will make your hand movements more natural.

- Warm up your facial muscles by chewing in a highly exaggerated way. Do shoulder and neck rolls. Imagine you are at eye level with a clock. As you look at 12 o’clock, pull as much of your face up to the 12 as you can; move your eyes to 3 and repeat, then down to 6, and finally over to 9.

Not only do these exercises warm you up but they also relax you. The exaggerated movements help your movements to flow more naturally.1

This is just the start

Thorough preparation is key to making a solid presentation. But other factors are important too. Your goal is for the audience to take action or to implement suggestions from your presentation. In part 2 of this series, we will share tips on elements of the presentation itself that will encourage audience engagement and message retention. We will discuss how to make your message “stick” and how to make a dynamic, effective presentation that holds your audience’s attention for your entire talk.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Fripp P. Add credibility to your business reputation through public speaking. Patricia Fripp website. http://www.fripp.com/add-credibility-to-your-business-reputation-through-public-speaking/. Accessed June 15, 2016.

Public speaking is one of the best ways to market and promote your skills as a physician. It is an ethical way of communicating and showcasing your areas of interest and expertise to professional or lay audiences. Most physicians and health care professionals take pride in their ability to communicate. After all, that is how we take a history, discuss our findings with patients, and educate individuals on restoring or maintaining their health. Public speaking, though, for the most part is a learned skill. Except for presentations to faculty at bedside or at grand rounds, we have received little training in public speaking.

Few of us are naturally comfortable in front of a live audience or a TV or video camera. But with a little practice and diligent preparation, we can become good or even excellent, confident public speakers. This article—the first in a series of 3—provides you with preparatory tips and techniques to enhance your public speaking skills.

First, know your audience

Whether you are presenting to a group of 20 or 200, you can do certain things in advance to ensure that your presentation achieves the desired response. Most important: Know your audience. Don’t assume the audience is like you. To connect with them, you need to understand why your topic is important to them. What do they expect to learn from the presentation? Each attendee will be asking, “What’s in it for me?”

To keep listeners interested and engaged, you also must know their level of knowledge about the topic. If you are speaking to a group of residents about pelvic organ prolapse, you would use different language and content than if you were speaking to practicing primary care doctors; and these elements would be different again if you were speaking to a group of practicing urogynecologists. It’s insulting to recite basic information to highly knowledgeable physicians, or to present sophisticated technical content and complicated slides to novice physicians or lay people.

When presenting in a foreign country, learn how the culture of the audience differs from yours. How do they dress? What style of humor do they favor? How do they typically communicate? What gestures are appropriate or inappropriate? Are there religious influences to consider?

Practical steps. Before the meeting or event, speak to the organizer or meeting planner and find out the audience’s level of knowledge on the topic. Ask about audience expectations as well as demographics (such as age and background). If you are speaking at an industry event, research the event’s website and familiarize yourself with the mission of the event and who are the typical attendees. If you are presenting to a corporation, learn as much as you can about it by visiting its website, reading news reports, and reviewing associated blogs.

In addition to knowing the needs of the audience, ask the meeting planner about the goals and objectives for the program to make certain you can deliver on the requests.

Know your talk stem to stern

Review your slide material thoroughly. Understand each slide in the presentation and be comfortable with its content.

Avoid reading from slides. Reciting content that viewers can read for themselves breeds boredom and makes them lose interest. Further, when you are looking at the slides, you are not making eye contact with the audience and risk losing their attention. Good speakers are so comfortable with their slides that they can discuss each one without having to look at it.

Rehearse. The best way to achieve the foregoing is to rehearse. Your audience will be able to tell if you took the slide deck directly from a CD and loaded it into a computer and are giving the talk for the first time. You’ll need to know how long the program is to last and how long you are to speak. We suggest you practice with a timer to be certain you do not exceed the allotted time. Rehearse your talk aloud several times with all the props and audiovisual equipment you plan to use. This practice will help to curb filler words such as “ah” and “um.” It is also helpful to practice slide transitions, pauses, and even your breathing.

Prepare for the unexpected, too. Dinner meetings, for instance, may not start on time due to office or hospital delays for attending physicians, possibly resulting in a need to shorten your presentation.

Ask about the meeting agenda. If a meal is to be served, will you be speaking beforehand? This is the least favorable time slot, as you are holding people hostage before they can eat. Our preference is to speak after the appetizer is served and the orders have been taken by the wait staff. This way, attendees are not starving and they have something to drink. You can assure the waiters they won’t be disturbing you, and you can ask them to avoid walking in front of the projector. Ideally, you should end your presentation before dessert arrives and use the remaining time to field questions.

We suggest that you prepare a handout to be distributed at the end of the program, not before. You want your audience focused on you and your slides as you are speaking. Tell the audience you will be providing a handout of your presentation, which will minimize note-taking during your talk.

Your speech opening

The first and last 30 seconds of any speech probably have the most impact.1 Give extra thought, time, and effort to your opening and closing remarks. Do not open with “Good evening, it is a pleasure to be here tonight.” That wastes precious seconds.

While opening a speech with a joke or funny story is the conventional wisdom, ask yourself1:

- Is my selection appropriate to the occasion and for this audience?

- Is it in good taste?

- Does it relate to me (my service) or to the event or the group? Does it support my topic or its key points?

A humorous story or inspirational vignette that relates to your topic or audience can grab the audience’s attention. If you feel that demands more presentation skill than you possess at the outset of your public-speaking career, give the audience what you know and what they most want to hear. You know the questions that you have heard most at cocktail receptions or professional society meetings. So, put the answers to those questions in your speech.

For example. A scientist working with a major corporation was preparing a speech for a lay audience. Since most of the audience did not know what scientists do, he offered the following analogy: “Being a scientist is like doing a jigsaw puzzle in a snowstorm at night...you don’t have all the pieces...and you don’t have the picture on the front of the box to work from.” You can say more with less.1

Your closing

The closing is an important aspect of your speech. Summarize the key elements to your presentation. If you are going to take questions, a good approach is to say, “Before my closing remarks, are there any questions?” Following the questions, finish with a takeaway message that ties into your theme.1

Prepare an autobiographical introduction

We suggest that you write your own introduction and e-mail it to the person who will be introducing you. Let them know it is a suggestion that they are welcome to modify. We have found that most emcees or meeting planners are delighted to have the introduction and will use it just as you have written it. Also bring hard copy with you; many emcees will have forgotten to download what you sent. The figure shows an example of the introduction that one of us (NHB) uses, and you are welcome to modify it for your own use.

Ask about and confirm audiovisual support

Ask the meeting planner ahead of time if they will be providing the computer, projector, and screen. And if, for instance, they will provide a projector but not a computer, make sure the computer you will bring is compatible with their projector. Also, you will probably not require a microphone for a small group, but if you are speaking in a loud restaurant, a portable microphone-speaker system may be helpful.

Arrive early at the program venue to make sure the computers, projector, screen placement, and seating arrangement are all in order. Nothing can sidetrack a speaker (even a seasoned one) like a problem with the computer or equipment setup—for example, your flash drive requiring a USB port cannot connect to the sponsor’s computer, or your program created on a Mac does not run on the sponsor’s PC.

Show time: Getting ready

Another benefit in arriving early, besides being able to check on the equipment, is the chance to greet the audience members as they enter. It is easier to speak to a group of friends than strangers. And if you can remember their names, you can call on them and ask their opinion or how they might manage a patient who has the condition you are discussing. You also could suggest to the meeting planner that name tags for attendees would be helpful.

Warming up. A public speaker, like an athlete, needs to warm up physically before the event. If the facility has an anteroom available, use it for the following exercises suggested by public speaking coach Patricia Fripp1:

- Stand on one leg and shake the other (remove high heels first). When you place your raised foot back on the floor, it will feel lighter than the other one. Repeat the exercise using the other leg. Imagine your energy going down through the floor and up out of your head. While this sounds quite comical, it is not. It is a practical technique used by actors.

- Shake your hands vigorously. Hold them above your head, bending your wrists and elbows, then return your arms to your sides. This will make your hand movements more natural.

- Warm up your facial muscles by chewing in a highly exaggerated way. Do shoulder and neck rolls. Imagine you are at eye level with a clock. As you look at 12 o’clock, pull as much of your face up to the 12 as you can; move your eyes to 3 and repeat, then down to 6, and finally over to 9.

Not only do these exercises warm you up but they also relax you. The exaggerated movements help your movements to flow more naturally.1

This is just the start

Thorough preparation is key to making a solid presentation. But other factors are important too. Your goal is for the audience to take action or to implement suggestions from your presentation. In part 2 of this series, we will share tips on elements of the presentation itself that will encourage audience engagement and message retention. We will discuss how to make your message “stick” and how to make a dynamic, effective presentation that holds your audience’s attention for your entire talk.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Public speaking is one of the best ways to market and promote your skills as a physician. It is an ethical way of communicating and showcasing your areas of interest and expertise to professional or lay audiences. Most physicians and health care professionals take pride in their ability to communicate. After all, that is how we take a history, discuss our findings with patients, and educate individuals on restoring or maintaining their health. Public speaking, though, for the most part is a learned skill. Except for presentations to faculty at bedside or at grand rounds, we have received little training in public speaking.

Few of us are naturally comfortable in front of a live audience or a TV or video camera. But with a little practice and diligent preparation, we can become good or even excellent, confident public speakers. This article—the first in a series of 3—provides you with preparatory tips and techniques to enhance your public speaking skills.

First, know your audience

Whether you are presenting to a group of 20 or 200, you can do certain things in advance to ensure that your presentation achieves the desired response. Most important: Know your audience. Don’t assume the audience is like you. To connect with them, you need to understand why your topic is important to them. What do they expect to learn from the presentation? Each attendee will be asking, “What’s in it for me?”

To keep listeners interested and engaged, you also must know their level of knowledge about the topic. If you are speaking to a group of residents about pelvic organ prolapse, you would use different language and content than if you were speaking to practicing primary care doctors; and these elements would be different again if you were speaking to a group of practicing urogynecologists. It’s insulting to recite basic information to highly knowledgeable physicians, or to present sophisticated technical content and complicated slides to novice physicians or lay people.

When presenting in a foreign country, learn how the culture of the audience differs from yours. How do they dress? What style of humor do they favor? How do they typically communicate? What gestures are appropriate or inappropriate? Are there religious influences to consider?

Practical steps. Before the meeting or event, speak to the organizer or meeting planner and find out the audience’s level of knowledge on the topic. Ask about audience expectations as well as demographics (such as age and background). If you are speaking at an industry event, research the event’s website and familiarize yourself with the mission of the event and who are the typical attendees. If you are presenting to a corporation, learn as much as you can about it by visiting its website, reading news reports, and reviewing associated blogs.

In addition to knowing the needs of the audience, ask the meeting planner about the goals and objectives for the program to make certain you can deliver on the requests.

Know your talk stem to stern

Review your slide material thoroughly. Understand each slide in the presentation and be comfortable with its content.

Avoid reading from slides. Reciting content that viewers can read for themselves breeds boredom and makes them lose interest. Further, when you are looking at the slides, you are not making eye contact with the audience and risk losing their attention. Good speakers are so comfortable with their slides that they can discuss each one without having to look at it.

Rehearse. The best way to achieve the foregoing is to rehearse. Your audience will be able to tell if you took the slide deck directly from a CD and loaded it into a computer and are giving the talk for the first time. You’ll need to know how long the program is to last and how long you are to speak. We suggest you practice with a timer to be certain you do not exceed the allotted time. Rehearse your talk aloud several times with all the props and audiovisual equipment you plan to use. This practice will help to curb filler words such as “ah” and “um.” It is also helpful to practice slide transitions, pauses, and even your breathing.

Prepare for the unexpected, too. Dinner meetings, for instance, may not start on time due to office or hospital delays for attending physicians, possibly resulting in a need to shorten your presentation.

Ask about the meeting agenda. If a meal is to be served, will you be speaking beforehand? This is the least favorable time slot, as you are holding people hostage before they can eat. Our preference is to speak after the appetizer is served and the orders have been taken by the wait staff. This way, attendees are not starving and they have something to drink. You can assure the waiters they won’t be disturbing you, and you can ask them to avoid walking in front of the projector. Ideally, you should end your presentation before dessert arrives and use the remaining time to field questions.

We suggest that you prepare a handout to be distributed at the end of the program, not before. You want your audience focused on you and your slides as you are speaking. Tell the audience you will be providing a handout of your presentation, which will minimize note-taking during your talk.

Your speech opening

The first and last 30 seconds of any speech probably have the most impact.1 Give extra thought, time, and effort to your opening and closing remarks. Do not open with “Good evening, it is a pleasure to be here tonight.” That wastes precious seconds.

While opening a speech with a joke or funny story is the conventional wisdom, ask yourself1:

- Is my selection appropriate to the occasion and for this audience?

- Is it in good taste?

- Does it relate to me (my service) or to the event or the group? Does it support my topic or its key points?

A humorous story or inspirational vignette that relates to your topic or audience can grab the audience’s attention. If you feel that demands more presentation skill than you possess at the outset of your public-speaking career, give the audience what you know and what they most want to hear. You know the questions that you have heard most at cocktail receptions or professional society meetings. So, put the answers to those questions in your speech.

For example. A scientist working with a major corporation was preparing a speech for a lay audience. Since most of the audience did not know what scientists do, he offered the following analogy: “Being a scientist is like doing a jigsaw puzzle in a snowstorm at night...you don’t have all the pieces...and you don’t have the picture on the front of the box to work from.” You can say more with less.1

Your closing

The closing is an important aspect of your speech. Summarize the key elements to your presentation. If you are going to take questions, a good approach is to say, “Before my closing remarks, are there any questions?” Following the questions, finish with a takeaway message that ties into your theme.1

Prepare an autobiographical introduction

We suggest that you write your own introduction and e-mail it to the person who will be introducing you. Let them know it is a suggestion that they are welcome to modify. We have found that most emcees or meeting planners are delighted to have the introduction and will use it just as you have written it. Also bring hard copy with you; many emcees will have forgotten to download what you sent. The figure shows an example of the introduction that one of us (NHB) uses, and you are welcome to modify it for your own use.

Ask about and confirm audiovisual support

Ask the meeting planner ahead of time if they will be providing the computer, projector, and screen. And if, for instance, they will provide a projector but not a computer, make sure the computer you will bring is compatible with their projector. Also, you will probably not require a microphone for a small group, but if you are speaking in a loud restaurant, a portable microphone-speaker system may be helpful.

Arrive early at the program venue to make sure the computers, projector, screen placement, and seating arrangement are all in order. Nothing can sidetrack a speaker (even a seasoned one) like a problem with the computer or equipment setup—for example, your flash drive requiring a USB port cannot connect to the sponsor’s computer, or your program created on a Mac does not run on the sponsor’s PC.

Show time: Getting ready

Another benefit in arriving early, besides being able to check on the equipment, is the chance to greet the audience members as they enter. It is easier to speak to a group of friends than strangers. And if you can remember their names, you can call on them and ask their opinion or how they might manage a patient who has the condition you are discussing. You also could suggest to the meeting planner that name tags for attendees would be helpful.

Warming up. A public speaker, like an athlete, needs to warm up physically before the event. If the facility has an anteroom available, use it for the following exercises suggested by public speaking coach Patricia Fripp1:

- Stand on one leg and shake the other (remove high heels first). When you place your raised foot back on the floor, it will feel lighter than the other one. Repeat the exercise using the other leg. Imagine your energy going down through the floor and up out of your head. While this sounds quite comical, it is not. It is a practical technique used by actors.

- Shake your hands vigorously. Hold them above your head, bending your wrists and elbows, then return your arms to your sides. This will make your hand movements more natural.

- Warm up your facial muscles by chewing in a highly exaggerated way. Do shoulder and neck rolls. Imagine you are at eye level with a clock. As you look at 12 o’clock, pull as much of your face up to the 12 as you can; move your eyes to 3 and repeat, then down to 6, and finally over to 9.

Not only do these exercises warm you up but they also relax you. The exaggerated movements help your movements to flow more naturally.1

This is just the start

Thorough preparation is key to making a solid presentation. But other factors are important too. Your goal is for the audience to take action or to implement suggestions from your presentation. In part 2 of this series, we will share tips on elements of the presentation itself that will encourage audience engagement and message retention. We will discuss how to make your message “stick” and how to make a dynamic, effective presentation that holds your audience’s attention for your entire talk.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Fripp P. Add credibility to your business reputation through public speaking. Patricia Fripp website. http://www.fripp.com/add-credibility-to-your-business-reputation-through-public-speaking/. Accessed June 15, 2016.

Reference

- Fripp P. Add credibility to your business reputation through public speaking. Patricia Fripp website. http://www.fripp.com/add-credibility-to-your-business-reputation-through-public-speaking/. Accessed June 15, 2016.

In this Article

- Preparing a presentation

- Your speech opening

- AV equipment and support