User login

An 88-year-old Caucasian man of Italian ancestry came into our clinic with multiple, painful purple-red “growths” on his left foot that he’d had for several years (FIGURE 1).

The patient had no systemic complaints (no fever, chills, weight loss, night sweats). He had a history of hypertension, a cardiac valve replacement, and chronic back pain (secondary to a motor vehicle accident). He was taking warfarin and nadolol.

The patient had multiple, 0.1– to 0.5-cm purple-red papules and nodules on the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the left foot, with associated moderate lower extremity edema and mottled dyspigmentation.

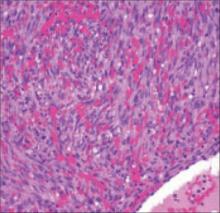

We did a punch biopsy, which showed a nodular neoplasm composed of moderately plump, spindle-shaped cells in short interweaving fascicles and numerous extravasated erythrocytes in the spaces (“vascular slits”) between the spindle-shaped cells (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1

Painful papules and nodules

FIGURE 2

Hematoxylin/eosin stain

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma is a rare mesenchymal tumor most often seen in elderly men of Mediterranean or Ashkenazi Jewish origin with an annual incidence in the United States of between 0.02% and 0.06%, with a peak occurring in the 5th to 8th decade of life.1 (Two-thirds of cases develop after the age of 50.) Population-based studies in the United States have shown a male-to-female ratio of 4:1.1

First described by the Hungarian dermatologist Moritz Kaposi in 1872, Kaposi’s sarcoma assumed prominence during the emerging HIV epidemic and is now the most common tumor in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).2

Recent research has implicated the human herpes virus–8 (HHV–8) as an inductive agent (necessary though not sufficient) in all epidemiologic subsets of the disease.2

There are 4 principal clinical variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma:

- classic (or chronic),

- African endemic (includes childhood lymphadenopathic),

- transplant-associated, and

- AIDS-related.

What you’ll see

Clinically, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma often first manifests as blue-red, well-demarcated, painless macules confined to the distal lower extremities.3 These slow-growing lesions may enlarge to forms papules and plaques, or progress to nodules and tumors. Unilateral involvement is often observed at the outset of the disease, with potential centripetal spread occurring late-in-course.3

Early lesions are generally soft, spongy, and “angiomatous,” while in the advanced state, lesional skin becomes hard, solid, and brown in color.3 Edema of the surrounding tissue is common. In addition to the skin, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma also involves mucosal sites (especially the oral and gastrointestinal mucosae).

Differential includes melanocytic nevus

A differential diagnosis for classic Kaposi’s sarcoma includes stasis dermatitis (“acroangiodermatitis”), melanocytic nevus, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, arthropod assault, and dermatofibroma/dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DF/DFSP).

Melanocytic nevi, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, and DF/DFSP ordinarily feature single lesions, while Kaposi’s sarcoma has multiple lesions. An arthropod assault is pruritic, and stasis dermatitis typically has dilated/varicose veins.

Histology will confirm your suspicions

While epidemiological and clinical factors may suggest classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, a final diagnosis ultimately rests on confirmatory histology. The pathology of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma (like all of the variant subtypes) is based solely on stage of the lesion.

Early patch-stage lesions exhibit papillary dermal proliferation of small, angulated vessels lined by bland endothelial cells with an accompanying sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

As the disease progresses to the plaque stage, the vascular proliferation expands into the reticular dermis and subcutis. The transition to nodular Kaposi’s sarcoma develops when a population of spindle cells expressing endothelial markers occurs between the “vascular slits” (FIGURE 2).

Chemotherapy for rapidly progressive disease

There is minimal evidence-based data for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Treatment options for limited disease include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical retinoids (alitretinoin), interferon-alpha, and radiation.1

If rapidly progressive disease (>10 new lesions per month) exists, the most effective treatment remains systemic chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin, vinblastine,4 bleomycin,4 or paclitaxel5). The benefits of chemotherapy can last for months—and even years.

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy does the trick

We treated our patient with liquid nitrogen cryotherapy that was applied at regular 4- to 6-week intervals over several months. After 3 months, our patient’s lesions were nearly resolved. We followed him monthly thereafter.

Correspondence

John Patrick Welsh, MD, Associates in Dermatology, 4727 Friendship Avenue, Suite 300, Pittsburgh, PA 15224-1778; [email protected].

1. Iscovich J, Boffetta P, Franceschi S, Azizi E, Sarid R. Classic Kaposi sarcoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Cancer. 2000;88:500-517.

2. Pellet C, Kerob D, Dupuy A, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viremia is associated with the progression of classic and endemic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:621-627.

3. Schwartz R. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

4. Brambilla L, Miedico A, Ferrucci S, et al. Combination of vinblastine and bleomycin as first line therapy in advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1090-1094.

5. Baskan EB, Tunali S, Adim SB, et al. Treatment of advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with weekly low-dose paclitaxel therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1441-1443.

An 88-year-old Caucasian man of Italian ancestry came into our clinic with multiple, painful purple-red “growths” on his left foot that he’d had for several years (FIGURE 1).

The patient had no systemic complaints (no fever, chills, weight loss, night sweats). He had a history of hypertension, a cardiac valve replacement, and chronic back pain (secondary to a motor vehicle accident). He was taking warfarin and nadolol.

The patient had multiple, 0.1– to 0.5-cm purple-red papules and nodules on the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the left foot, with associated moderate lower extremity edema and mottled dyspigmentation.

We did a punch biopsy, which showed a nodular neoplasm composed of moderately plump, spindle-shaped cells in short interweaving fascicles and numerous extravasated erythrocytes in the spaces (“vascular slits”) between the spindle-shaped cells (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1

Painful papules and nodules

FIGURE 2

Hematoxylin/eosin stain

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma is a rare mesenchymal tumor most often seen in elderly men of Mediterranean or Ashkenazi Jewish origin with an annual incidence in the United States of between 0.02% and 0.06%, with a peak occurring in the 5th to 8th decade of life.1 (Two-thirds of cases develop after the age of 50.) Population-based studies in the United States have shown a male-to-female ratio of 4:1.1

First described by the Hungarian dermatologist Moritz Kaposi in 1872, Kaposi’s sarcoma assumed prominence during the emerging HIV epidemic and is now the most common tumor in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).2

Recent research has implicated the human herpes virus–8 (HHV–8) as an inductive agent (necessary though not sufficient) in all epidemiologic subsets of the disease.2

There are 4 principal clinical variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma:

- classic (or chronic),

- African endemic (includes childhood lymphadenopathic),

- transplant-associated, and

- AIDS-related.

What you’ll see

Clinically, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma often first manifests as blue-red, well-demarcated, painless macules confined to the distal lower extremities.3 These slow-growing lesions may enlarge to forms papules and plaques, or progress to nodules and tumors. Unilateral involvement is often observed at the outset of the disease, with potential centripetal spread occurring late-in-course.3

Early lesions are generally soft, spongy, and “angiomatous,” while in the advanced state, lesional skin becomes hard, solid, and brown in color.3 Edema of the surrounding tissue is common. In addition to the skin, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma also involves mucosal sites (especially the oral and gastrointestinal mucosae).

Differential includes melanocytic nevus

A differential diagnosis for classic Kaposi’s sarcoma includes stasis dermatitis (“acroangiodermatitis”), melanocytic nevus, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, arthropod assault, and dermatofibroma/dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DF/DFSP).

Melanocytic nevi, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, and DF/DFSP ordinarily feature single lesions, while Kaposi’s sarcoma has multiple lesions. An arthropod assault is pruritic, and stasis dermatitis typically has dilated/varicose veins.

Histology will confirm your suspicions

While epidemiological and clinical factors may suggest classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, a final diagnosis ultimately rests on confirmatory histology. The pathology of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma (like all of the variant subtypes) is based solely on stage of the lesion.

Early patch-stage lesions exhibit papillary dermal proliferation of small, angulated vessels lined by bland endothelial cells with an accompanying sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

As the disease progresses to the plaque stage, the vascular proliferation expands into the reticular dermis and subcutis. The transition to nodular Kaposi’s sarcoma develops when a population of spindle cells expressing endothelial markers occurs between the “vascular slits” (FIGURE 2).

Chemotherapy for rapidly progressive disease

There is minimal evidence-based data for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Treatment options for limited disease include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical retinoids (alitretinoin), interferon-alpha, and radiation.1

If rapidly progressive disease (>10 new lesions per month) exists, the most effective treatment remains systemic chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin, vinblastine,4 bleomycin,4 or paclitaxel5). The benefits of chemotherapy can last for months—and even years.

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy does the trick

We treated our patient with liquid nitrogen cryotherapy that was applied at regular 4- to 6-week intervals over several months. After 3 months, our patient’s lesions were nearly resolved. We followed him monthly thereafter.

Correspondence

John Patrick Welsh, MD, Associates in Dermatology, 4727 Friendship Avenue, Suite 300, Pittsburgh, PA 15224-1778; [email protected].

An 88-year-old Caucasian man of Italian ancestry came into our clinic with multiple, painful purple-red “growths” on his left foot that he’d had for several years (FIGURE 1).

The patient had no systemic complaints (no fever, chills, weight loss, night sweats). He had a history of hypertension, a cardiac valve replacement, and chronic back pain (secondary to a motor vehicle accident). He was taking warfarin and nadolol.

The patient had multiple, 0.1– to 0.5-cm purple-red papules and nodules on the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the left foot, with associated moderate lower extremity edema and mottled dyspigmentation.

We did a punch biopsy, which showed a nodular neoplasm composed of moderately plump, spindle-shaped cells in short interweaving fascicles and numerous extravasated erythrocytes in the spaces (“vascular slits”) between the spindle-shaped cells (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1

Painful papules and nodules

FIGURE 2

Hematoxylin/eosin stain

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma is a rare mesenchymal tumor most often seen in elderly men of Mediterranean or Ashkenazi Jewish origin with an annual incidence in the United States of between 0.02% and 0.06%, with a peak occurring in the 5th to 8th decade of life.1 (Two-thirds of cases develop after the age of 50.) Population-based studies in the United States have shown a male-to-female ratio of 4:1.1

First described by the Hungarian dermatologist Moritz Kaposi in 1872, Kaposi’s sarcoma assumed prominence during the emerging HIV epidemic and is now the most common tumor in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).2

Recent research has implicated the human herpes virus–8 (HHV–8) as an inductive agent (necessary though not sufficient) in all epidemiologic subsets of the disease.2

There are 4 principal clinical variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma:

- classic (or chronic),

- African endemic (includes childhood lymphadenopathic),

- transplant-associated, and

- AIDS-related.

What you’ll see

Clinically, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma often first manifests as blue-red, well-demarcated, painless macules confined to the distal lower extremities.3 These slow-growing lesions may enlarge to forms papules and plaques, or progress to nodules and tumors. Unilateral involvement is often observed at the outset of the disease, with potential centripetal spread occurring late-in-course.3

Early lesions are generally soft, spongy, and “angiomatous,” while in the advanced state, lesional skin becomes hard, solid, and brown in color.3 Edema of the surrounding tissue is common. In addition to the skin, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma also involves mucosal sites (especially the oral and gastrointestinal mucosae).

Differential includes melanocytic nevus

A differential diagnosis for classic Kaposi’s sarcoma includes stasis dermatitis (“acroangiodermatitis”), melanocytic nevus, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, arthropod assault, and dermatofibroma/dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DF/DFSP).

Melanocytic nevi, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, and DF/DFSP ordinarily feature single lesions, while Kaposi’s sarcoma has multiple lesions. An arthropod assault is pruritic, and stasis dermatitis typically has dilated/varicose veins.

Histology will confirm your suspicions

While epidemiological and clinical factors may suggest classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, a final diagnosis ultimately rests on confirmatory histology. The pathology of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma (like all of the variant subtypes) is based solely on stage of the lesion.

Early patch-stage lesions exhibit papillary dermal proliferation of small, angulated vessels lined by bland endothelial cells with an accompanying sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

As the disease progresses to the plaque stage, the vascular proliferation expands into the reticular dermis and subcutis. The transition to nodular Kaposi’s sarcoma develops when a population of spindle cells expressing endothelial markers occurs between the “vascular slits” (FIGURE 2).

Chemotherapy for rapidly progressive disease

There is minimal evidence-based data for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Treatment options for limited disease include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical retinoids (alitretinoin), interferon-alpha, and radiation.1

If rapidly progressive disease (>10 new lesions per month) exists, the most effective treatment remains systemic chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin, vinblastine,4 bleomycin,4 or paclitaxel5). The benefits of chemotherapy can last for months—and even years.

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy does the trick

We treated our patient with liquid nitrogen cryotherapy that was applied at regular 4- to 6-week intervals over several months. After 3 months, our patient’s lesions were nearly resolved. We followed him monthly thereafter.

Correspondence

John Patrick Welsh, MD, Associates in Dermatology, 4727 Friendship Avenue, Suite 300, Pittsburgh, PA 15224-1778; [email protected].

1. Iscovich J, Boffetta P, Franceschi S, Azizi E, Sarid R. Classic Kaposi sarcoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Cancer. 2000;88:500-517.

2. Pellet C, Kerob D, Dupuy A, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viremia is associated with the progression of classic and endemic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:621-627.

3. Schwartz R. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

4. Brambilla L, Miedico A, Ferrucci S, et al. Combination of vinblastine and bleomycin as first line therapy in advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1090-1094.

5. Baskan EB, Tunali S, Adim SB, et al. Treatment of advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with weekly low-dose paclitaxel therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1441-1443.

1. Iscovich J, Boffetta P, Franceschi S, Azizi E, Sarid R. Classic Kaposi sarcoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Cancer. 2000;88:500-517.

2. Pellet C, Kerob D, Dupuy A, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viremia is associated with the progression of classic and endemic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:621-627.

3. Schwartz R. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

4. Brambilla L, Miedico A, Ferrucci S, et al. Combination of vinblastine and bleomycin as first line therapy in advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1090-1094.

5. Baskan EB, Tunali S, Adim SB, et al. Treatment of advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with weekly low-dose paclitaxel therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1441-1443.