User login

Deck: Study finds overall high quality of care but identifies important gaps in assessment and treatment.

Active-duty service members with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression are frequent users of both inpatient and outpatient Military Health System (MHS) care, but there were significant variations in the quality and type of care they received, according to a recent RAND Corporation study. According to the authors, the MHS “performed well in providing initial screening for suicide and substance abuse but needs to improve at providing adequate follow-up to service members with suicide risk.”

The Quality of Care for PTSD and Depression in the Military Health System study is the third in a series of reports on the quality of depression and PTSD care for active-duty service members. The study examined data for 2013-2014 and included 14,654 service members with PTSD and 30,496 with depression; 6,322 service members were in both groups. The goal of the report was to determine whether the service members with PTSD or depression receive evidence-based care and whether there were disparities in care quality by branch of service, geographic region, and other characteristics, such as gender, age, pay grade, race/ethnicity, or deployment history.

Related: New Center of Excellence to Lead Research of “Signature Wounds”

In both the PTSD and depression cohorts, the majority of active-component service members were enlisted soldiers and had 1 or more deployments. A large number of patients were in both the PTSD and depression cohorts. The study noted that more than half of patients in the PTSD cohort had a diagnosis of depression, and more than one-fourth of those in the depression cohort received a PTSD diagnosis during the 12-month observation period.

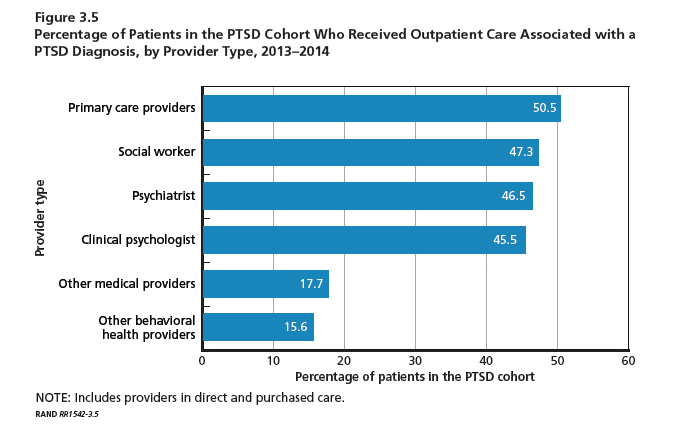

Service members with PTSD or depression were willing to engage the health system with medians of 40 and 31 visits for PTSD and depression, respectively, during the 1-year observation period. Most of these visits were for unrelated conditions. Importantly, more than half of patients received their care from primary care providers. Social workers, psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists provided care for slightly less than half of the PTSD cohort. These mental health provider groups saw between 33% and 40% of the depression cohort. The majority of patients in both the PTSD and depression cohorts received care for their cohort diagnosis solely at military treatment facilities

“The high utilization for both medical and psychological conditions combined with the high number of different providers raise questions about the extent of coordination vs fragmentation of care for all the care these service members received,” the study reported. “The high number of psychotherapy visits received by members of these cohorts suggests that the MHS may be more successful than the civilian sector in engaging patients with PTSD or depression in psychosocial interventions.”

The study also highlighted the following important gaps in treatment, assessment, and follow-up:

- Assessment of baseline symptom severity of PTSD for a new treatment episode with the PCL (PTSD Checklist) was not as frequent, though current efforts are under way within the MHS to increase the regular use of the PCL to monitor PTSD patient symptoms.

- Standardized tools were used in less than half of the assessments for depression, suicide risk, and recent substance use and almost never used for assessment of function.

- Appropriate minimal care for patients with suicidal ideation was less than optimal (54%), primarily due to a lack of documentation regarding addressing access to lethal means. A Safety Plan Worksheet has recently been added to the clinical guideline for assessment and management of suicide risk which may improve this performance in the future.

- Most service members with PTSD or depression received at least some psychotherapy, but the MHS could increase delivery of evidence-based psychotherapy.

- Improvements are still needed in rates of outcome monitoring and performance on outcome measures.

- Multiple “statistically significant and clinically meaningful differences” were found in measure scores by service branch, TRICARE region, and service member.

Deck: Study finds overall high quality of care but identifies important gaps in assessment and treatment.

Active-duty service members with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression are frequent users of both inpatient and outpatient Military Health System (MHS) care, but there were significant variations in the quality and type of care they received, according to a recent RAND Corporation study. According to the authors, the MHS “performed well in providing initial screening for suicide and substance abuse but needs to improve at providing adequate follow-up to service members with suicide risk.”

The Quality of Care for PTSD and Depression in the Military Health System study is the third in a series of reports on the quality of depression and PTSD care for active-duty service members. The study examined data for 2013-2014 and included 14,654 service members with PTSD and 30,496 with depression; 6,322 service members were in both groups. The goal of the report was to determine whether the service members with PTSD or depression receive evidence-based care and whether there were disparities in care quality by branch of service, geographic region, and other characteristics, such as gender, age, pay grade, race/ethnicity, or deployment history.

Related: New Center of Excellence to Lead Research of “Signature Wounds”

In both the PTSD and depression cohorts, the majority of active-component service members were enlisted soldiers and had 1 or more deployments. A large number of patients were in both the PTSD and depression cohorts. The study noted that more than half of patients in the PTSD cohort had a diagnosis of depression, and more than one-fourth of those in the depression cohort received a PTSD diagnosis during the 12-month observation period.

Service members with PTSD or depression were willing to engage the health system with medians of 40 and 31 visits for PTSD and depression, respectively, during the 1-year observation period. Most of these visits were for unrelated conditions. Importantly, more than half of patients received their care from primary care providers. Social workers, psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists provided care for slightly less than half of the PTSD cohort. These mental health provider groups saw between 33% and 40% of the depression cohort. The majority of patients in both the PTSD and depression cohorts received care for their cohort diagnosis solely at military treatment facilities

“The high utilization for both medical and psychological conditions combined with the high number of different providers raise questions about the extent of coordination vs fragmentation of care for all the care these service members received,” the study reported. “The high number of psychotherapy visits received by members of these cohorts suggests that the MHS may be more successful than the civilian sector in engaging patients with PTSD or depression in psychosocial interventions.”

The study also highlighted the following important gaps in treatment, assessment, and follow-up:

- Assessment of baseline symptom severity of PTSD for a new treatment episode with the PCL (PTSD Checklist) was not as frequent, though current efforts are under way within the MHS to increase the regular use of the PCL to monitor PTSD patient symptoms.

- Standardized tools were used in less than half of the assessments for depression, suicide risk, and recent substance use and almost never used for assessment of function.

- Appropriate minimal care for patients with suicidal ideation was less than optimal (54%), primarily due to a lack of documentation regarding addressing access to lethal means. A Safety Plan Worksheet has recently been added to the clinical guideline for assessment and management of suicide risk which may improve this performance in the future.

- Most service members with PTSD or depression received at least some psychotherapy, but the MHS could increase delivery of evidence-based psychotherapy.

- Improvements are still needed in rates of outcome monitoring and performance on outcome measures.

- Multiple “statistically significant and clinically meaningful differences” were found in measure scores by service branch, TRICARE region, and service member.

Deck: Study finds overall high quality of care but identifies important gaps in assessment and treatment.

Active-duty service members with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression are frequent users of both inpatient and outpatient Military Health System (MHS) care, but there were significant variations in the quality and type of care they received, according to a recent RAND Corporation study. According to the authors, the MHS “performed well in providing initial screening for suicide and substance abuse but needs to improve at providing adequate follow-up to service members with suicide risk.”

The Quality of Care for PTSD and Depression in the Military Health System study is the third in a series of reports on the quality of depression and PTSD care for active-duty service members. The study examined data for 2013-2014 and included 14,654 service members with PTSD and 30,496 with depression; 6,322 service members were in both groups. The goal of the report was to determine whether the service members with PTSD or depression receive evidence-based care and whether there were disparities in care quality by branch of service, geographic region, and other characteristics, such as gender, age, pay grade, race/ethnicity, or deployment history.

Related: New Center of Excellence to Lead Research of “Signature Wounds”

In both the PTSD and depression cohorts, the majority of active-component service members were enlisted soldiers and had 1 or more deployments. A large number of patients were in both the PTSD and depression cohorts. The study noted that more than half of patients in the PTSD cohort had a diagnosis of depression, and more than one-fourth of those in the depression cohort received a PTSD diagnosis during the 12-month observation period.

Service members with PTSD or depression were willing to engage the health system with medians of 40 and 31 visits for PTSD and depression, respectively, during the 1-year observation period. Most of these visits were for unrelated conditions. Importantly, more than half of patients received their care from primary care providers. Social workers, psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists provided care for slightly less than half of the PTSD cohort. These mental health provider groups saw between 33% and 40% of the depression cohort. The majority of patients in both the PTSD and depression cohorts received care for their cohort diagnosis solely at military treatment facilities

“The high utilization for both medical and psychological conditions combined with the high number of different providers raise questions about the extent of coordination vs fragmentation of care for all the care these service members received,” the study reported. “The high number of psychotherapy visits received by members of these cohorts suggests that the MHS may be more successful than the civilian sector in engaging patients with PTSD or depression in psychosocial interventions.”

The study also highlighted the following important gaps in treatment, assessment, and follow-up:

- Assessment of baseline symptom severity of PTSD for a new treatment episode with the PCL (PTSD Checklist) was not as frequent, though current efforts are under way within the MHS to increase the regular use of the PCL to monitor PTSD patient symptoms.

- Standardized tools were used in less than half of the assessments for depression, suicide risk, and recent substance use and almost never used for assessment of function.

- Appropriate minimal care for patients with suicidal ideation was less than optimal (54%), primarily due to a lack of documentation regarding addressing access to lethal means. A Safety Plan Worksheet has recently been added to the clinical guideline for assessment and management of suicide risk which may improve this performance in the future.

- Most service members with PTSD or depression received at least some psychotherapy, but the MHS could increase delivery of evidence-based psychotherapy.

- Improvements are still needed in rates of outcome monitoring and performance on outcome measures.

- Multiple “statistically significant and clinically meaningful differences” were found in measure scores by service branch, TRICARE region, and service member.