User login

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our dermatology clinic with the self-diagnosis of “recurrent shingles,” noting that she’d had a rash over her sacrum on and off for the past 10 years. She said that the tender blisters typically appeared in this area 3 to 4 times per year (FIGURE) and that their onset was occasionally associated with stress. The rash tended to resolve—without treatment—within 5 to 7 days. The patient had no other medical problems or symptoms. Physical examination revealed 3 groups of vesicular lesions, each on an erythematous base, located bilaterally over the gluteal cleft.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Recurrent herpes simplex virus-2

While the presentation of herpes zoster (shingles) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) is similar—grouped vesicles on an erythematous base—recurrent shingles is rare in immunocompetent patients. Also, the herpes zoster rash is generally unilateral and is not common on the buttocks.1,2

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) generally occurs around the mouth. Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) is generally a genital rash. (Our patient was not aware that she’d had a genital primary HSV-2 infection.) That said, non-genital recurrences in the sacral region and lower extremities occur in up to 60% of patients whose primary genital HSV-2 infection also involved non-genital sites.3

HSV-2 infects an estimated 5% to 25% of adults in western nations.4 In 2012, approximately 417 million people ages 15 to 49 were living with HSV-2 worldwide, including 19 million who were newly infected.5

A dormant infection that is reactivated. Following a genital primary infection, HSV-2 lies dormant in the sacral nerve root ganglia, which innervate both the genitals and sacrum. Reactivation can thus result in recurrences anywhere over the sacral dermatome.6 The sacral area is the most common non-genital site for recurrent HSV-2.3 Reactivation of HSV-2 is more common and more severe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.7

Neurologic complications in some patients with genital herpes (eg, sacral radiculopathy, hyperesthesia) reinforce the hypothesis that genital herpes can infect ganglia that are also associated with sacral nerves.8 Contrary to popular belief, sacral HSV-2 is not commonly contracted from toilet seats.

How to differentiate herpes simplex from herpes zoster

As noted earlier, the location of the vesicles and unilateral nature of herpes zoster are useful in differentiating HSV from herpes zoster.

Tzanck preparation can’t be used to differentiate HSV and herpes zoster because it will demonstrate multinucleated giant cells in both cases. When necessary, viral culture can be used to distinguish the 2 conditions, although HSV often takes 24 to 72 hours to grow and herpes zoster may take up to 2 weeks.9,10 Increasingly, polymerase chain reaction is being used for this purpose.

Antivirals are used for both genital and non-genital recurrences

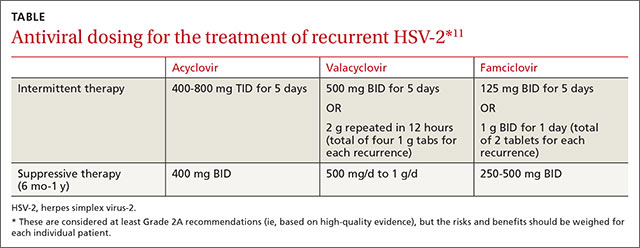

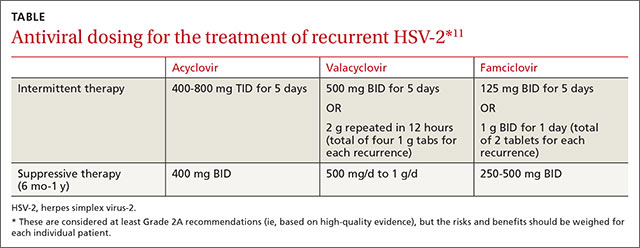

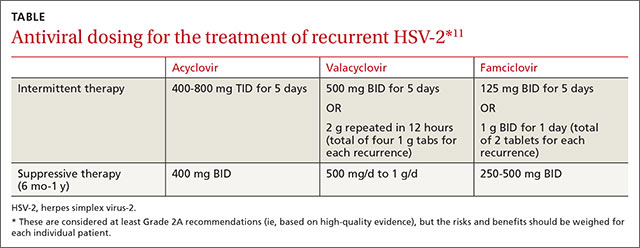

The mainstay of treatment for HSV is antiviral therapy with acyclovir. Famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used as well (TABLE).11 These antivirals inhibit viral DNA replication, shorten duration of symptoms, increase lesion healing, and decrease viral shedding time.12 They are generally safe; the main adverse effects of oral therapy are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

In general, non-genital recurrences of HSV are treated the same as genital recurrences.13 Dosing during prodromal symptoms, or at the first sign of a recurrence is recommended for maximum efficacy.13 Suppressive therapy can be effective in patients who experience frequent recurrences and is generally recommended for 6 months to a year or longer.

Patients should also be warned that because of increased genital viral shedding during sacral recurrences, they should avoid sexual contact during outbreaks.14

Our patient began taking oral valacyclovir 1 g daily and had no recurrences over the next year.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, et al. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1605-1609.

2. Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

3. Benedetti JK, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Frequency and reactivation of nongenital lesions among patients with genital herpes simplex virus. Am J Med. 1995;98:237-242.

4. Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186 Suppl 1:S3-S28.

5. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KME, et al. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e114989.

6. Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, et al. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:958-972.

7. Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

8. Ooi C, Zawar V. Hyperaesthesia following genital herpes: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:903595.

9. Domeika M, Bashmakova M, Savicheva A, et al; Eastern European Network for Sexual and Reproductive Health (EE SRH Network). Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of genital herpes in eastern European countries. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(44). pii:19703.

10. Solomon AR, Rasmussen JE, Weiss JS. A comparison of the Tzanck smear and viral isolation in varicella and herpes zoster. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:282-285.

11. Cernik C, Gallina K, Brodell RT. The treatment of herpes simplex infections: an evidence-based review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1137-1144.

12. Goldberg LH, Kaufman R, Conant MA, et al. Oral acyclovir for episodic treatment of recurrent genital herpes. Efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:256-264.

13. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: McGraw-Hill:2005;800-803.

14. Kerkering K, Gardella C, Selke S, et al. Isolation of herpes simplex virus from the genital tract during symptomatic recurrence on the buttocks. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:947-952.

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our dermatology clinic with the self-diagnosis of “recurrent shingles,” noting that she’d had a rash over her sacrum on and off for the past 10 years. She said that the tender blisters typically appeared in this area 3 to 4 times per year (FIGURE) and that their onset was occasionally associated with stress. The rash tended to resolve—without treatment—within 5 to 7 days. The patient had no other medical problems or symptoms. Physical examination revealed 3 groups of vesicular lesions, each on an erythematous base, located bilaterally over the gluteal cleft.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Recurrent herpes simplex virus-2

While the presentation of herpes zoster (shingles) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) is similar—grouped vesicles on an erythematous base—recurrent shingles is rare in immunocompetent patients. Also, the herpes zoster rash is generally unilateral and is not common on the buttocks.1,2

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) generally occurs around the mouth. Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) is generally a genital rash. (Our patient was not aware that she’d had a genital primary HSV-2 infection.) That said, non-genital recurrences in the sacral region and lower extremities occur in up to 60% of patients whose primary genital HSV-2 infection also involved non-genital sites.3

HSV-2 infects an estimated 5% to 25% of adults in western nations.4 In 2012, approximately 417 million people ages 15 to 49 were living with HSV-2 worldwide, including 19 million who were newly infected.5

A dormant infection that is reactivated. Following a genital primary infection, HSV-2 lies dormant in the sacral nerve root ganglia, which innervate both the genitals and sacrum. Reactivation can thus result in recurrences anywhere over the sacral dermatome.6 The sacral area is the most common non-genital site for recurrent HSV-2.3 Reactivation of HSV-2 is more common and more severe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.7

Neurologic complications in some patients with genital herpes (eg, sacral radiculopathy, hyperesthesia) reinforce the hypothesis that genital herpes can infect ganglia that are also associated with sacral nerves.8 Contrary to popular belief, sacral HSV-2 is not commonly contracted from toilet seats.

How to differentiate herpes simplex from herpes zoster

As noted earlier, the location of the vesicles and unilateral nature of herpes zoster are useful in differentiating HSV from herpes zoster.

Tzanck preparation can’t be used to differentiate HSV and herpes zoster because it will demonstrate multinucleated giant cells in both cases. When necessary, viral culture can be used to distinguish the 2 conditions, although HSV often takes 24 to 72 hours to grow and herpes zoster may take up to 2 weeks.9,10 Increasingly, polymerase chain reaction is being used for this purpose.

Antivirals are used for both genital and non-genital recurrences

The mainstay of treatment for HSV is antiviral therapy with acyclovir. Famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used as well (TABLE).11 These antivirals inhibit viral DNA replication, shorten duration of symptoms, increase lesion healing, and decrease viral shedding time.12 They are generally safe; the main adverse effects of oral therapy are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

In general, non-genital recurrences of HSV are treated the same as genital recurrences.13 Dosing during prodromal symptoms, or at the first sign of a recurrence is recommended for maximum efficacy.13 Suppressive therapy can be effective in patients who experience frequent recurrences and is generally recommended for 6 months to a year or longer.

Patients should also be warned that because of increased genital viral shedding during sacral recurrences, they should avoid sexual contact during outbreaks.14

Our patient began taking oral valacyclovir 1 g daily and had no recurrences over the next year.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our dermatology clinic with the self-diagnosis of “recurrent shingles,” noting that she’d had a rash over her sacrum on and off for the past 10 years. She said that the tender blisters typically appeared in this area 3 to 4 times per year (FIGURE) and that their onset was occasionally associated with stress. The rash tended to resolve—without treatment—within 5 to 7 days. The patient had no other medical problems or symptoms. Physical examination revealed 3 groups of vesicular lesions, each on an erythematous base, located bilaterally over the gluteal cleft.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Recurrent herpes simplex virus-2

While the presentation of herpes zoster (shingles) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) is similar—grouped vesicles on an erythematous base—recurrent shingles is rare in immunocompetent patients. Also, the herpes zoster rash is generally unilateral and is not common on the buttocks.1,2

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) generally occurs around the mouth. Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) is generally a genital rash. (Our patient was not aware that she’d had a genital primary HSV-2 infection.) That said, non-genital recurrences in the sacral region and lower extremities occur in up to 60% of patients whose primary genital HSV-2 infection also involved non-genital sites.3

HSV-2 infects an estimated 5% to 25% of adults in western nations.4 In 2012, approximately 417 million people ages 15 to 49 were living with HSV-2 worldwide, including 19 million who were newly infected.5

A dormant infection that is reactivated. Following a genital primary infection, HSV-2 lies dormant in the sacral nerve root ganglia, which innervate both the genitals and sacrum. Reactivation can thus result in recurrences anywhere over the sacral dermatome.6 The sacral area is the most common non-genital site for recurrent HSV-2.3 Reactivation of HSV-2 is more common and more severe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.7

Neurologic complications in some patients with genital herpes (eg, sacral radiculopathy, hyperesthesia) reinforce the hypothesis that genital herpes can infect ganglia that are also associated with sacral nerves.8 Contrary to popular belief, sacral HSV-2 is not commonly contracted from toilet seats.

How to differentiate herpes simplex from herpes zoster

As noted earlier, the location of the vesicles and unilateral nature of herpes zoster are useful in differentiating HSV from herpes zoster.

Tzanck preparation can’t be used to differentiate HSV and herpes zoster because it will demonstrate multinucleated giant cells in both cases. When necessary, viral culture can be used to distinguish the 2 conditions, although HSV often takes 24 to 72 hours to grow and herpes zoster may take up to 2 weeks.9,10 Increasingly, polymerase chain reaction is being used for this purpose.

Antivirals are used for both genital and non-genital recurrences

The mainstay of treatment for HSV is antiviral therapy with acyclovir. Famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used as well (TABLE).11 These antivirals inhibit viral DNA replication, shorten duration of symptoms, increase lesion healing, and decrease viral shedding time.12 They are generally safe; the main adverse effects of oral therapy are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

In general, non-genital recurrences of HSV are treated the same as genital recurrences.13 Dosing during prodromal symptoms, or at the first sign of a recurrence is recommended for maximum efficacy.13 Suppressive therapy can be effective in patients who experience frequent recurrences and is generally recommended for 6 months to a year or longer.

Patients should also be warned that because of increased genital viral shedding during sacral recurrences, they should avoid sexual contact during outbreaks.14

Our patient began taking oral valacyclovir 1 g daily and had no recurrences over the next year.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, et al. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1605-1609.

2. Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

3. Benedetti JK, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Frequency and reactivation of nongenital lesions among patients with genital herpes simplex virus. Am J Med. 1995;98:237-242.

4. Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186 Suppl 1:S3-S28.

5. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KME, et al. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e114989.

6. Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, et al. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:958-972.

7. Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

8. Ooi C, Zawar V. Hyperaesthesia following genital herpes: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:903595.

9. Domeika M, Bashmakova M, Savicheva A, et al; Eastern European Network for Sexual and Reproductive Health (EE SRH Network). Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of genital herpes in eastern European countries. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(44). pii:19703.

10. Solomon AR, Rasmussen JE, Weiss JS. A comparison of the Tzanck smear and viral isolation in varicella and herpes zoster. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:282-285.

11. Cernik C, Gallina K, Brodell RT. The treatment of herpes simplex infections: an evidence-based review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1137-1144.

12. Goldberg LH, Kaufman R, Conant MA, et al. Oral acyclovir for episodic treatment of recurrent genital herpes. Efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:256-264.

13. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: McGraw-Hill:2005;800-803.

14. Kerkering K, Gardella C, Selke S, et al. Isolation of herpes simplex virus from the genital tract during symptomatic recurrence on the buttocks. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:947-952.

1. Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, et al. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1605-1609.

2. Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

3. Benedetti JK, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Frequency and reactivation of nongenital lesions among patients with genital herpes simplex virus. Am J Med. 1995;98:237-242.

4. Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186 Suppl 1:S3-S28.

5. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KME, et al. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e114989.

6. Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, et al. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:958-972.

7. Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

8. Ooi C, Zawar V. Hyperaesthesia following genital herpes: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:903595.

9. Domeika M, Bashmakova M, Savicheva A, et al; Eastern European Network for Sexual and Reproductive Health (EE SRH Network). Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of genital herpes in eastern European countries. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(44). pii:19703.

10. Solomon AR, Rasmussen JE, Weiss JS. A comparison of the Tzanck smear and viral isolation in varicella and herpes zoster. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:282-285.

11. Cernik C, Gallina K, Brodell RT. The treatment of herpes simplex infections: an evidence-based review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1137-1144.

12. Goldberg LH, Kaufman R, Conant MA, et al. Oral acyclovir for episodic treatment of recurrent genital herpes. Efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:256-264.

13. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: McGraw-Hill:2005;800-803.

14. Kerkering K, Gardella C, Selke S, et al. Isolation of herpes simplex virus from the genital tract during symptomatic recurrence on the buttocks. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:947-952.