User login

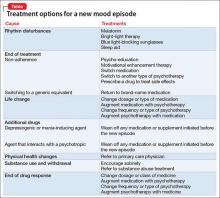

A mood disorder is a chronic illness, associated with episodic recurrence over time1,2; when a patient experiences a new mood episode, explore possible underlying causes of that recurrence. The mnemonic RELAPSE can help you take an informed approach to treatment, instead of making reflexive medication changes (Table).

Rhythm disturbances. Seasonal changes, shift work, jet lag, and sleep irregularity can induce a mood episode in a vulnerable patient. Failure of a patient’s circadian clock to resynchronize itself after such disruption in the dark–light cycle can trigger mood symptoms.

Ending treatment. Intentional or unintentional non-adherence to a prescribed medication or psychotherapy can trigger a mood episode. Likewise, switching from a brand-name medication to a generic equivalent can induce a new episode because the generic drug might be as much as 20% less bioavailable than the brand formulation.3

Life change. Some life events, such as divorce or job loss, can be sufficiently overwhelming—despite medical therapy and psychotherapy—to induce a new episode in a vulnerable patient.

Additional drugs. Opiates, interferon, steroids, reserpine, and other drugs can be depressogenic; on the other hand, steroids, anticholinergic agents, and antidepressants can induce mania. If another physician, or the patient, adds a medication or supplement that causes an interaction with the patient’s current psychotropic prescription, the result might be increased metabolism or clearance of the psychotropic—thus decreasing its efficacy and leading to a new mood episode.

Physical health changes. Neurologic conditions (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke), autoimmune illnesses (eg, lupus), primary sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), and hormone changes (eg, testosterone, estrogen, and thyroid) that can occur over the lifespan of a patient with a mood disorder can trigger a new episode.

Substance use and withdrawal. Chronic use of alcohol and opiates and withdrawal from cocaine and stimulants in a patient with a mood disorder can induce a depressive episode; use of cocaine, stimulants, and caffeine can induce a manic state.

End of drug response. Some patients experience a loss of drug response over time (tachyphylaxis) or a depressive recurrence while taking an antidepressant.4 These phenomena might be caused by brain changes over time. These are a diagnosis of exclusion after other possibilities have been ruled out.

1. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229-233.

2. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217-224.

3. Ellingrod VL. How differences among generics might affect your patient’s response. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):31-32,38.

4. Dunlop BW. Depressive recurrence on antidepressant treatment (DRAT): 4 next-step options. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:54-55.

A mood disorder is a chronic illness, associated with episodic recurrence over time1,2; when a patient experiences a new mood episode, explore possible underlying causes of that recurrence. The mnemonic RELAPSE can help you take an informed approach to treatment, instead of making reflexive medication changes (Table).

Rhythm disturbances. Seasonal changes, shift work, jet lag, and sleep irregularity can induce a mood episode in a vulnerable patient. Failure of a patient’s circadian clock to resynchronize itself after such disruption in the dark–light cycle can trigger mood symptoms.

Ending treatment. Intentional or unintentional non-adherence to a prescribed medication or psychotherapy can trigger a mood episode. Likewise, switching from a brand-name medication to a generic equivalent can induce a new episode because the generic drug might be as much as 20% less bioavailable than the brand formulation.3

Life change. Some life events, such as divorce or job loss, can be sufficiently overwhelming—despite medical therapy and psychotherapy—to induce a new episode in a vulnerable patient.

Additional drugs. Opiates, interferon, steroids, reserpine, and other drugs can be depressogenic; on the other hand, steroids, anticholinergic agents, and antidepressants can induce mania. If another physician, or the patient, adds a medication or supplement that causes an interaction with the patient’s current psychotropic prescription, the result might be increased metabolism or clearance of the psychotropic—thus decreasing its efficacy and leading to a new mood episode.

Physical health changes. Neurologic conditions (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke), autoimmune illnesses (eg, lupus), primary sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), and hormone changes (eg, testosterone, estrogen, and thyroid) that can occur over the lifespan of a patient with a mood disorder can trigger a new episode.

Substance use and withdrawal. Chronic use of alcohol and opiates and withdrawal from cocaine and stimulants in a patient with a mood disorder can induce a depressive episode; use of cocaine, stimulants, and caffeine can induce a manic state.

End of drug response. Some patients experience a loss of drug response over time (tachyphylaxis) or a depressive recurrence while taking an antidepressant.4 These phenomena might be caused by brain changes over time. These are a diagnosis of exclusion after other possibilities have been ruled out.

A mood disorder is a chronic illness, associated with episodic recurrence over time1,2; when a patient experiences a new mood episode, explore possible underlying causes of that recurrence. The mnemonic RELAPSE can help you take an informed approach to treatment, instead of making reflexive medication changes (Table).

Rhythm disturbances. Seasonal changes, shift work, jet lag, and sleep irregularity can induce a mood episode in a vulnerable patient. Failure of a patient’s circadian clock to resynchronize itself after such disruption in the dark–light cycle can trigger mood symptoms.

Ending treatment. Intentional or unintentional non-adherence to a prescribed medication or psychotherapy can trigger a mood episode. Likewise, switching from a brand-name medication to a generic equivalent can induce a new episode because the generic drug might be as much as 20% less bioavailable than the brand formulation.3

Life change. Some life events, such as divorce or job loss, can be sufficiently overwhelming—despite medical therapy and psychotherapy—to induce a new episode in a vulnerable patient.

Additional drugs. Opiates, interferon, steroids, reserpine, and other drugs can be depressogenic; on the other hand, steroids, anticholinergic agents, and antidepressants can induce mania. If another physician, or the patient, adds a medication or supplement that causes an interaction with the patient’s current psychotropic prescription, the result might be increased metabolism or clearance of the psychotropic—thus decreasing its efficacy and leading to a new mood episode.

Physical health changes. Neurologic conditions (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke), autoimmune illnesses (eg, lupus), primary sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), and hormone changes (eg, testosterone, estrogen, and thyroid) that can occur over the lifespan of a patient with a mood disorder can trigger a new episode.

Substance use and withdrawal. Chronic use of alcohol and opiates and withdrawal from cocaine and stimulants in a patient with a mood disorder can induce a depressive episode; use of cocaine, stimulants, and caffeine can induce a manic state.

End of drug response. Some patients experience a loss of drug response over time (tachyphylaxis) or a depressive recurrence while taking an antidepressant.4 These phenomena might be caused by brain changes over time. These are a diagnosis of exclusion after other possibilities have been ruled out.

1. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229-233.

2. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217-224.

3. Ellingrod VL. How differences among generics might affect your patient’s response. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):31-32,38.

4. Dunlop BW. Depressive recurrence on antidepressant treatment (DRAT): 4 next-step options. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:54-55.

1. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229-233.

2. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217-224.

3. Ellingrod VL. How differences among generics might affect your patient’s response. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):31-32,38.

4. Dunlop BW. Depressive recurrence on antidepressant treatment (DRAT): 4 next-step options. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:54-55.