User login

Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

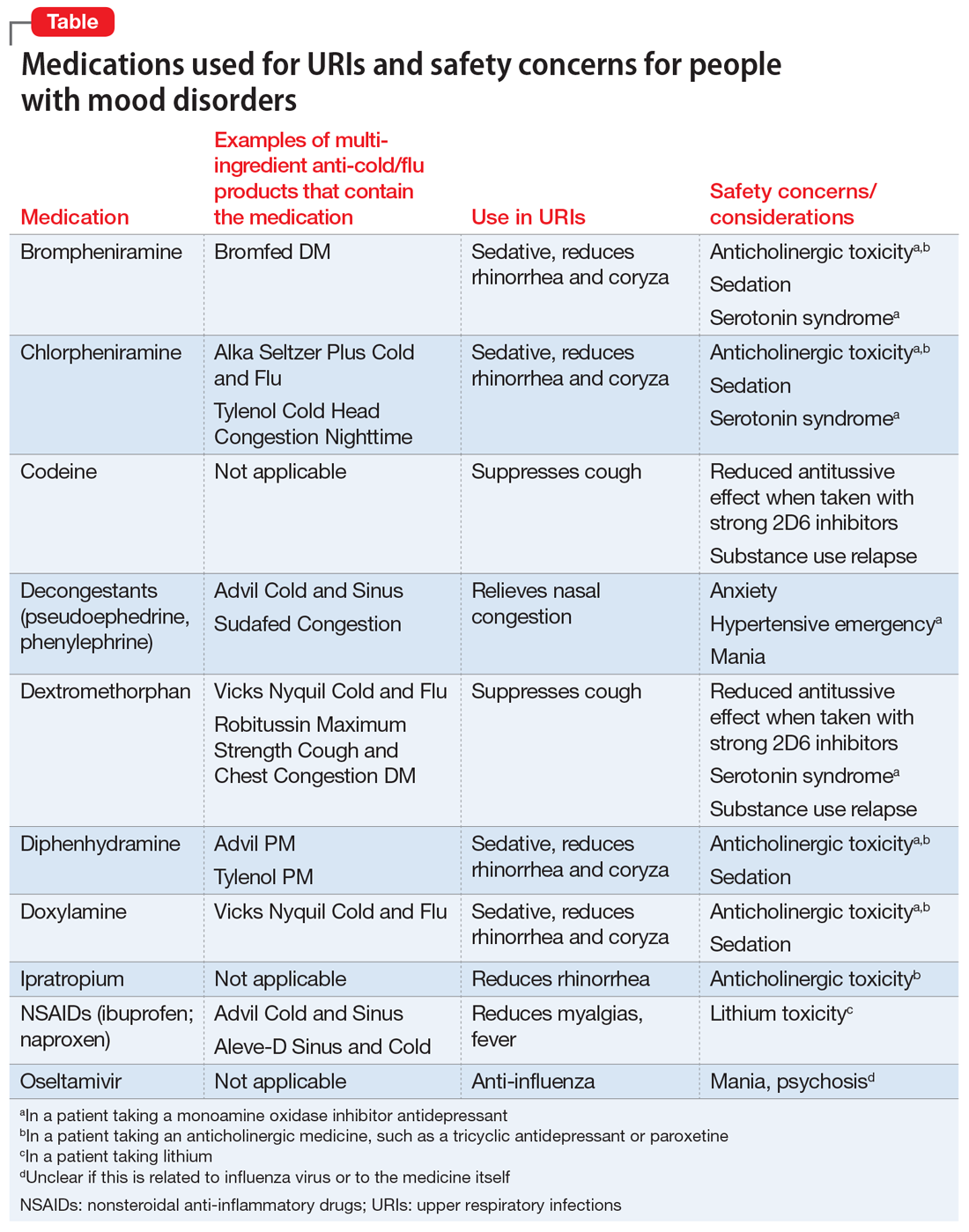

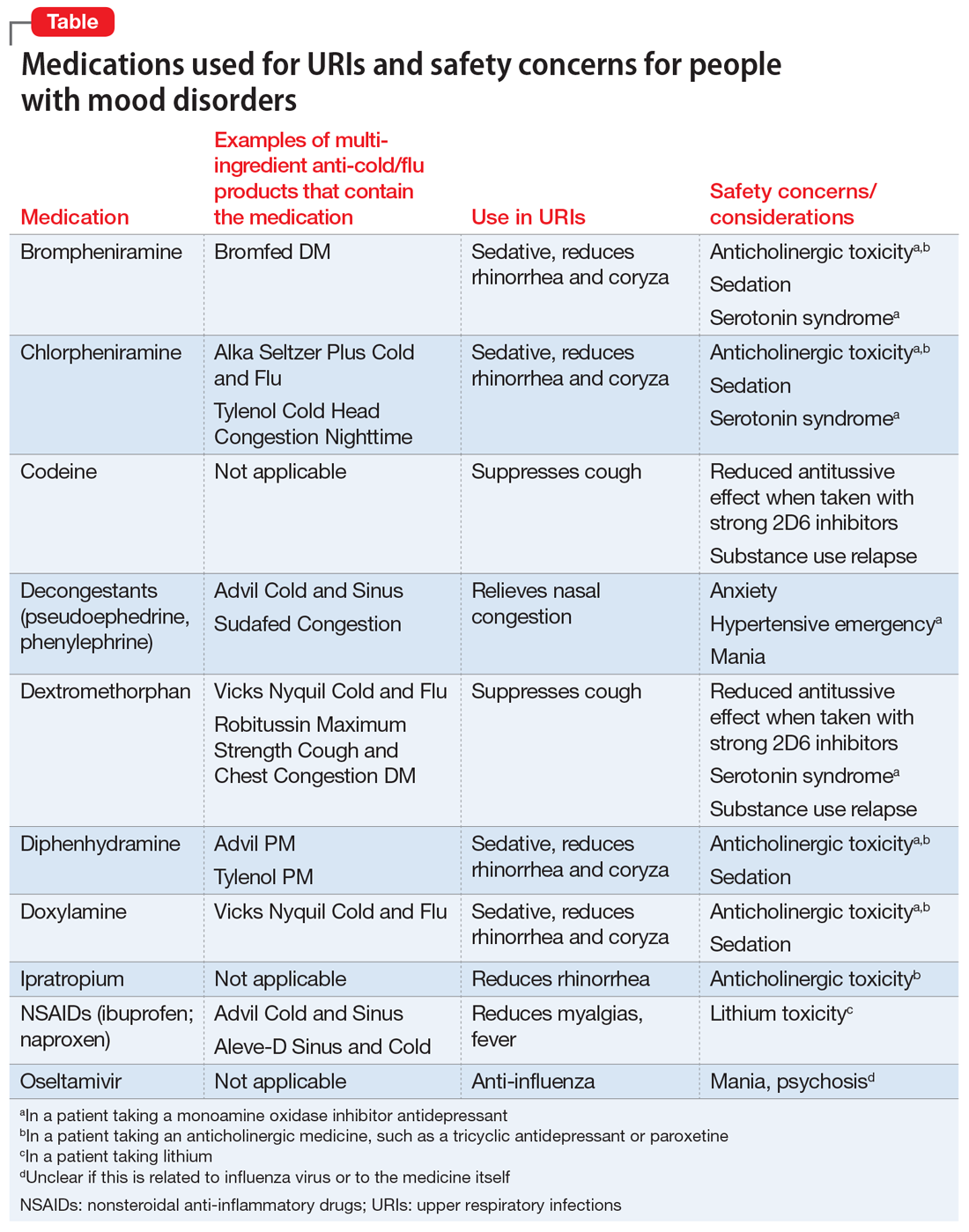

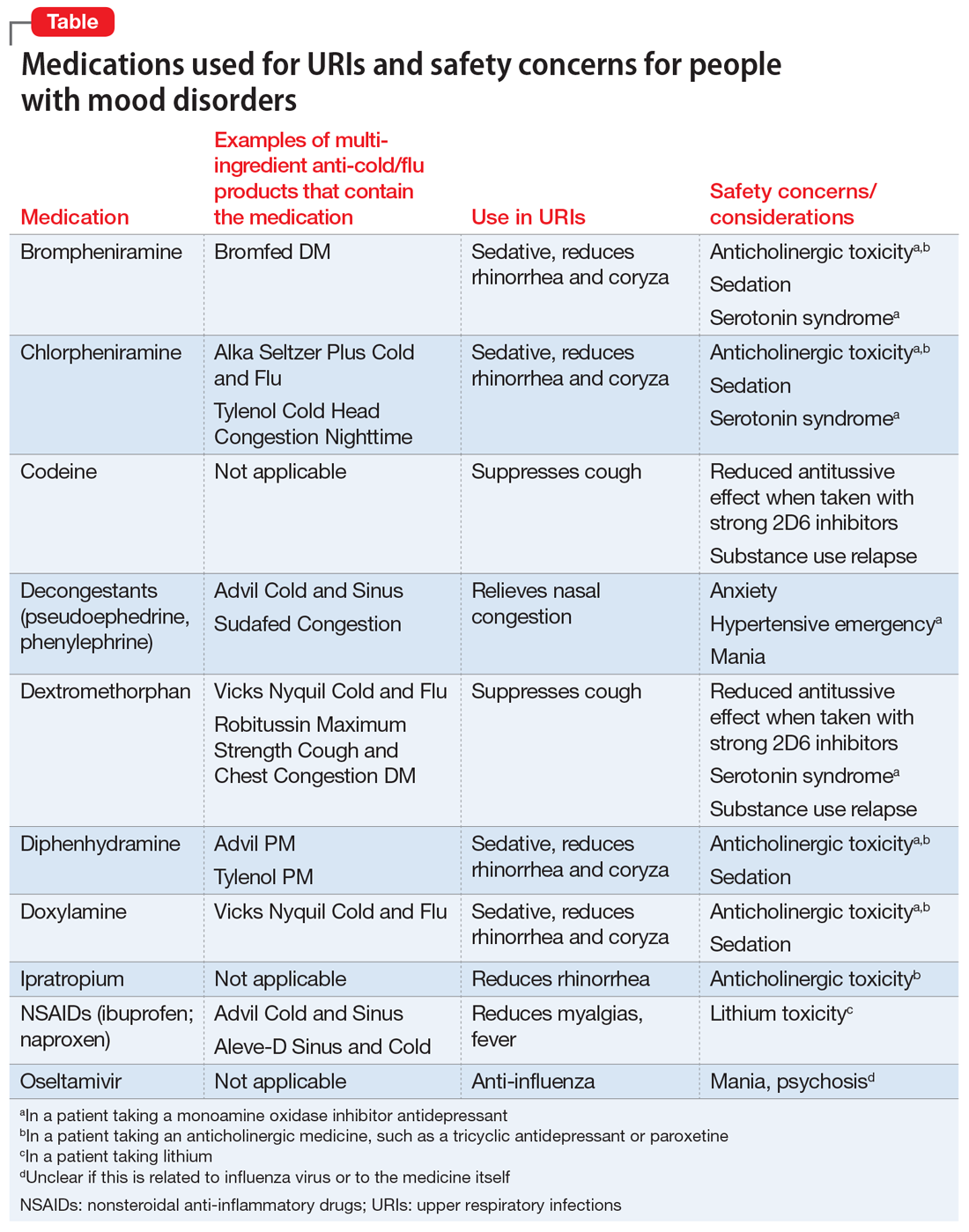

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.

32. Ho LN, Chung JP, Choy KL. Oseltamivir-induced mania in a patient with H1N1. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):350.

33. Jeon SW, Han C. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with influenza A (H1N1) treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu): a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):209-211.

34. Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):190-199.

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.

32. Ho LN, Chung JP, Choy KL. Oseltamivir-induced mania in a patient with H1N1. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):350.

33. Jeon SW, Han C. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with influenza A (H1N1) treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu): a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):209-211.

34. Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):190-199.

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.

32. Ho LN, Chung JP, Choy KL. Oseltamivir-induced mania in a patient with H1N1. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):350.

33. Jeon SW, Han C. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with influenza A (H1N1) treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu): a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):209-211.

34. Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):190-199.

RELAPSE: Answers to why a patient is having a new mood episode

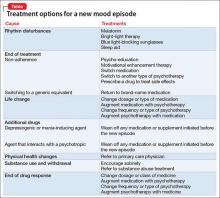

A mood disorder is a chronic illness, associated with episodic recurrence over time1,2; when a patient experiences a new mood episode, explore possible underlying causes of that recurrence. The mnemonic RELAPSE can help you take an informed approach to treatment, instead of making reflexive medication changes (Table).

Rhythm disturbances. Seasonal changes, shift work, jet lag, and sleep irregularity can induce a mood episode in a vulnerable patient. Failure of a patient’s circadian clock to resynchronize itself after such disruption in the dark–light cycle can trigger mood symptoms.

Ending treatment. Intentional or unintentional non-adherence to a prescribed medication or psychotherapy can trigger a mood episode. Likewise, switching from a brand-name medication to a generic equivalent can induce a new episode because the generic drug might be as much as 20% less bioavailable than the brand formulation.3

Life change. Some life events, such as divorce or job loss, can be sufficiently overwhelming—despite medical therapy and psychotherapy—to induce a new episode in a vulnerable patient.

Additional drugs. Opiates, interferon, steroids, reserpine, and other drugs can be depressogenic; on the other hand, steroids, anticholinergic agents, and antidepressants can induce mania. If another physician, or the patient, adds a medication or supplement that causes an interaction with the patient’s current psychotropic prescription, the result might be increased metabolism or clearance of the psychotropic—thus decreasing its efficacy and leading to a new mood episode.

Physical health changes. Neurologic conditions (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke), autoimmune illnesses (eg, lupus), primary sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), and hormone changes (eg, testosterone, estrogen, and thyroid) that can occur over the lifespan of a patient with a mood disorder can trigger a new episode.

Substance use and withdrawal. Chronic use of alcohol and opiates and withdrawal from cocaine and stimulants in a patient with a mood disorder can induce a depressive episode; use of cocaine, stimulants, and caffeine can induce a manic state.

End of drug response. Some patients experience a loss of drug response over time (tachyphylaxis) or a depressive recurrence while taking an antidepressant.4 These phenomena might be caused by brain changes over time. These are a diagnosis of exclusion after other possibilities have been ruled out.

1. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229-233.

2. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217-224.

3. Ellingrod VL. How differences among generics might affect your patient’s response. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):31-32,38.

4. Dunlop BW. Depressive recurrence on antidepressant treatment (DRAT): 4 next-step options. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:54-55.

A mood disorder is a chronic illness, associated with episodic recurrence over time1,2; when a patient experiences a new mood episode, explore possible underlying causes of that recurrence. The mnemonic RELAPSE can help you take an informed approach to treatment, instead of making reflexive medication changes (Table).

Rhythm disturbances. Seasonal changes, shift work, jet lag, and sleep irregularity can induce a mood episode in a vulnerable patient. Failure of a patient’s circadian clock to resynchronize itself after such disruption in the dark–light cycle can trigger mood symptoms.

Ending treatment. Intentional or unintentional non-adherence to a prescribed medication or psychotherapy can trigger a mood episode. Likewise, switching from a brand-name medication to a generic equivalent can induce a new episode because the generic drug might be as much as 20% less bioavailable than the brand formulation.3

Life change. Some life events, such as divorce or job loss, can be sufficiently overwhelming—despite medical therapy and psychotherapy—to induce a new episode in a vulnerable patient.

Additional drugs. Opiates, interferon, steroids, reserpine, and other drugs can be depressogenic; on the other hand, steroids, anticholinergic agents, and antidepressants can induce mania. If another physician, or the patient, adds a medication or supplement that causes an interaction with the patient’s current psychotropic prescription, the result might be increased metabolism or clearance of the psychotropic—thus decreasing its efficacy and leading to a new mood episode.

Physical health changes. Neurologic conditions (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke), autoimmune illnesses (eg, lupus), primary sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), and hormone changes (eg, testosterone, estrogen, and thyroid) that can occur over the lifespan of a patient with a mood disorder can trigger a new episode.

Substance use and withdrawal. Chronic use of alcohol and opiates and withdrawal from cocaine and stimulants in a patient with a mood disorder can induce a depressive episode; use of cocaine, stimulants, and caffeine can induce a manic state.

End of drug response. Some patients experience a loss of drug response over time (tachyphylaxis) or a depressive recurrence while taking an antidepressant.4 These phenomena might be caused by brain changes over time. These are a diagnosis of exclusion after other possibilities have been ruled out.

A mood disorder is a chronic illness, associated with episodic recurrence over time1,2; when a patient experiences a new mood episode, explore possible underlying causes of that recurrence. The mnemonic RELAPSE can help you take an informed approach to treatment, instead of making reflexive medication changes (Table).

Rhythm disturbances. Seasonal changes, shift work, jet lag, and sleep irregularity can induce a mood episode in a vulnerable patient. Failure of a patient’s circadian clock to resynchronize itself after such disruption in the dark–light cycle can trigger mood symptoms.

Ending treatment. Intentional or unintentional non-adherence to a prescribed medication or psychotherapy can trigger a mood episode. Likewise, switching from a brand-name medication to a generic equivalent can induce a new episode because the generic drug might be as much as 20% less bioavailable than the brand formulation.3

Life change. Some life events, such as divorce or job loss, can be sufficiently overwhelming—despite medical therapy and psychotherapy—to induce a new episode in a vulnerable patient.

Additional drugs. Opiates, interferon, steroids, reserpine, and other drugs can be depressogenic; on the other hand, steroids, anticholinergic agents, and antidepressants can induce mania. If another physician, or the patient, adds a medication or supplement that causes an interaction with the patient’s current psychotropic prescription, the result might be increased metabolism or clearance of the psychotropic—thus decreasing its efficacy and leading to a new mood episode.

Physical health changes. Neurologic conditions (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke), autoimmune illnesses (eg, lupus), primary sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), and hormone changes (eg, testosterone, estrogen, and thyroid) that can occur over the lifespan of a patient with a mood disorder can trigger a new episode.

Substance use and withdrawal. Chronic use of alcohol and opiates and withdrawal from cocaine and stimulants in a patient with a mood disorder can induce a depressive episode; use of cocaine, stimulants, and caffeine can induce a manic state.

End of drug response. Some patients experience a loss of drug response over time (tachyphylaxis) or a depressive recurrence while taking an antidepressant.4 These phenomena might be caused by brain changes over time. These are a diagnosis of exclusion after other possibilities have been ruled out.

1. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229-233.

2. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217-224.

3. Ellingrod VL. How differences among generics might affect your patient’s response. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):31-32,38.

4. Dunlop BW. Depressive recurrence on antidepressant treatment (DRAT): 4 next-step options. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:54-55.

1. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229-233.

2. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217-224.

3. Ellingrod VL. How differences among generics might affect your patient’s response. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):31-32,38.

4. Dunlop BW. Depressive recurrence on antidepressant treatment (DRAT): 4 next-step options. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:54-55.

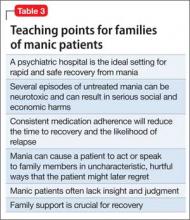

Outpatient mania

Treating bipolar mania in the outpatient setting: Risk vs reward

Manic episodes, by definition, are associated with significant social or occupational impairment.1 Some manic patients are violent or engage in reckless behaviors that can harm themselves or others, such as speeding, disrupting traffic, or playing with fire. When these patients present to a psychiatrist’s outpatient practice, involuntary hospitalization might be justified.

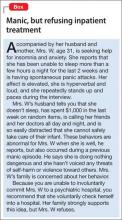

However, some manic patients, in spite of their elevated, expansive, or irritable mood state, never behave dangerously and might not meet legal criteria for involuntary hospitalization, although these criteria differ from state to state. These patients might see a psychiatrist because manic symptoms such as irritability, talkativeness, and impulsivity are bothersome to their family members but pose no serious danger (Box). In this situation, the psychiatrist can strongly encourage the patient to seek voluntary hospitalization or attend a partial hospitalization program. If the patient declines, the psychiatrist is left with 2 choices: initiate treatment in the outpatient setting or refuse to treat the patient and refer to another provider.

Treating “non-dangerous” mania in the outpatient setting is fraught with challenges:

• the possibility that the patient’s condition will progress to dangerousness

• poor adherence to treatment because of the patient’s limited insight

• the large amount of time required from the psychiatrist and care team to adequately manage the manic episode (eg, time spent with family members, frequent patient visits, and managing communications from the patient).

There are no guidelines to assist the office-based practitioner in treating mania in the outpatient setting. When considering dosing and optimal medication combinations for treating mania, clinical trials may be of limited value because most of these studies only included hospitalized manic patients.

Because of this dearth of knowledge, we provide recommendations based on our review of the literature and from our experience working with manic patients who refuse voluntary hospitalization and could not be hospitalized against their will. These recommendations are organized into 3 sections: diagnostic approach, treatment strategy, and family involvement.

Diagnostic approach

Making a diagnosis of mania might seem straightforward for clinicians who work in inpatient settings; however, mania might not present with classic florid symptoms among outpatients. Patients might have a chief concern of irritability, dysphoria, anxiety, or “insomnia,” which may lead clinicians to focus initially on non-bipolar conditions.2

During the interview, it is important to assess for any current DSM-5 symptoms of a manic episode, while being careful not to accept a patient’s denial of symptoms. Patients with mania often have poor insight and are unaware of changes from their baseline state when manic.3 Alternatively, manic patients may want you to believe that they are well and could minimize or deny all symptoms. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to mental status examination findings, such as hyperverbal speech, elated affect, psychomotor agitation, a tangential thought process, or flight of ideas.

Countertransference feelings of diagnostic confusion or frustration after long patient monologues or multiple interruptions by the patient should be incorporated into the diagnostic assessment. Family members or friends often can provide objective observations of behavioral changes necessary to secure the diagnosis.

Treatment strategy

Decision points. When treating manic outpatients, assess the need for hospitalization at each visit. Advantages of the inpatient setting include:

• the possibility of rapid medication adjustments

• continuous observation to ensure the patient’s safety

• keeping the patient temporarily removed from his community to prevent irreversible social and economic harms.

However, a challenge with hospitalization is third-party payers’ influence on a patient’s length of stay, which may lead to rapid medication changes that may not be clinically ideal.

At each outpatient visit, explore with the patient and family emerging symptoms that could justify involuntary hospitalization. Document whether you recommended inpatient hospitalization, the patient’s response to the recommendation, that you are aware and have considered the risks associated with outpatient care, and that you have discussed these risks with the patient and family.

For patients well-known to the psychiatrist, a history of dangerous mania may lead him (her) to strongly recommend hospitalization, whereas a pre-existing therapeutic alliance and no current or distant history of dangerous mania may lead the clinician to look for alternatives to inpatient care. Concomitant drug or alcohol use may increase the likelihood of mania becoming dangerous, making outpatient treatment ill-advised and riskier for everyone involved.

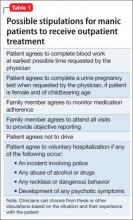

In exchange for agreeing to provide outpatient care for mania, it often is helpful to negotiate with the patient and family a threshold level of symptoms or behavior that will result in the patient agreeing to voluntary hospitalization (Table 1). Such an agreement can include stopping outpatient treatment if the patient does not improve significantly after 2 or 3 weeks or develops psychotic symptoms. The negotiation also can include partial hospitalization as an option, so long as the patient’s mania continues to be non-dangerous.

Obtaining pretreatment blood work can help a clinician determine whether a medication is safe to prescribe and establish causality if laboratory abnormalities arise after treatment begins. Ideally, the psychiatrist should follow consensus guidelines developed by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders4 or the American Psychiatric Association (APA)5 and order appropriate laboratory tests before prescribing anti-manic medications. Determine the pregnancy status of female patients of child-bearing age before prescribing a potentially teratogenic medication, especially because mania is associated with increased libido.6

Manic patients might be too disorganized to follow up with recommendations for laboratory testing, or could wait several days before completing blood work. Although not ideal, to avoid delaying treatment, a clinician might need to prescribe medication at the initial office visit, without pretreatment laboratory results. When the patient is more organized, complete the blood work. Keeping home pregnancy tests in the office can help rule out pregnancy before prescribing medication.

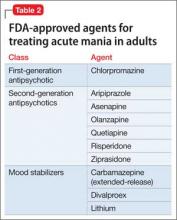

Medication. Meta-analyses have established the efficacy of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics for treating mania,7,8 and several consensus guidelines have incorporated these findings into treatment algorithms.9

For a patient already taking medications recommended by the guidelines, assess treatment adherence during the initial interview by questioning the patient and family. When the logistics of phlebotomy permit, obtaining the blood level of psychotropics can show the presence of any detectable drug concentration, which demonstrates that the patient has taken the medication recently.

If there is no evidence of nonadherence, an initial step might be to increase the dosage of the antipsychotic or mood stabilizer that the patient is already taking, ensuring that the dosage is optimized based on FDA indications and clinical trials data. The recommended rate of dosage adjustments differs among medications; however, optimal dosing should be reached quickly because a World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry task force recommends that a mania treatment trial not exceed 2 weeks.10

Dosage increases can be made at weekly visits or sooner, based on treatment response and tolerability. If there is no benefit after optimizing the dosage, the next step would be to add a mood stabilizer to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), or vice versa to promote additive or synergistic medication effects.11 Switching one medication for the other should be avoided unless there are tolerability concerns.

For a patient who is not taking any medications, select a treatment that balances rapid stabilization with long-term efficacy and tolerability. Table 2 lists FDA-approved treatments for mania. Lamotrigine provides prophylactic efficacy with few associated risks, but it has no anti-manic effects and would be a poor choice for most actively manic patients. Most studies indicate that antipsychotics work faster than lithium at the 1-week mark; however, this may be a function of the lithium titration schedule followed in the protocols, the severity of mania among enrolled patients, the inclusion of typically non-responsive manic patients (eg, mixed) in the analysis, and the antipsychotic’s sedative potential relative to lithium. Although the anti-manic and prophylactic potential of lithium and valproate might make them an ideal first-line option, antipsychotics could stabilize a manic patient faster, especially if agitation is present.12,13

Breaking mania quickly is important when treating patients in the outpatient setting. In these situations, a reasonable choice is to prescribe a SGA, because of their rapid onset of effect, low potential for switch to depression, and utility in treating classic, mixed, or psychotic mania.10 Oral loading of valproate (20 mg/kg) is another option. An inpatient study that used an oral-loading strategy demonstrated a similar time to response as olanzapine,14 in contrast to an inpatient15 and an outpatient study16 that employed a standard starting dosage for each patient and led to slower improvement compared with olanzapine.

SGAs should be dosed moderately and lower than if the patient were hospitalized, to avoid alienating the patient from treatment by causing intolerable side effects. In particular, patients and their families should be warned about immediate risks, such as orthostasis or extrapyramidal symptoms. Although treatment guidelines recommend combination therapy as a possible first-line option,9 in the outpatient setting, monotherapy with an optimally dosed, rapid-acting agent is preferred to promote medication adherence and avoid potentially dangerous sedation. Manic patients experience increased distractibility and verbal memory and executive function impairments that can interfere with medication adherence.17 Therefore, patients are more likely to follow a simpler regimen. If SGA or valproate monotherapy does not control mania, begin combination treatment with a mood stabilizer and SGA. If the patient experiences remission with SGA monotherapy, the risks and benefits of maintaining the SGA vs switching to a mood stabilizer can be discussed.

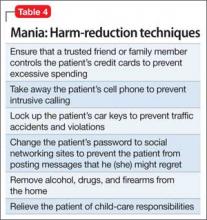

Provide medication “as needed” for agitation—additional SGA dosing or a benzodiazepine—and explain to family members when their use is warranted. Benzodiazepines can provide short-term benefits for manic patients: anxiety relief, sedation, and anti-manic efficacy as monotherapy18-20 and in combination with other medications.21 Studies showing monotherapy efficacy employed high dosages of benzodiazepines (lorazepam mean dosage, 14 mg/d; clonazepam mean dosage, 13 mg/d)19 and high dosages of antipsychotics as needed,18,20 and often were associated with excessive sedation and ataxia.18,19 This makes benzodiazepine monotherapy a potentially dangerous approach for outpatient treatment of mania. IM lorazepam treated manic agitation less quickly than IM olanzapine, suggesting that SGAs are preferable in the outpatient setting because rapid control of agitation is crucial.22 If prescribed, a trusted family member should dispense benzodiazepines to the patient to minimize misuse because of impulsivity, distractibility, desperation to sleep, or pleasure seeking.

SGAs have the benefit of sedation but occasionally additional sleep medications are required. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs), such as zolpidem, eszopiclone, and zaleplon, should be used with caution. Although these medicines are effective in treating insomnia in individuals with primary insomnia23 and major depression,24 they have not been studied in manic patients. The decreased need for sleep in mania is phenomenologically25 and perhaps biologically different than insomnia in major depression.26 Therefore, mania-associated sleep disturbance might not respond to BZRAs. BzRAs also might induce somnambulism and other parasomnias,27 especially when used in combination with psychotropics, such as valproate28; it is unclear if the manic state itself increases this risk further. Sedating antihistamines with anticholinergic blockade, such as diphenhydramine and low dosages (<100 mg/d) of quetiapine, are best used only in combination with anti-manic medications because of putative link between anticholinergic blockade and manic induction.29 Less studied but safer options include novel anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin), melatonin, and melatonin receptor agonists. Sedating antidepressants, such as mirtazapine and trazodone, should be avoided.25

Important adjunctive treatment steps include discontinuing all pro-manic agents, including antidepressants, stimulants, and steroids, and discouraging use of caffeine, energy drinks, illicit drugs, and alcohol. The patient should return for office visits at least weekly, and possibly more frequently, depending on severity. Telephone check-in calls between scheduled visits may be necessary until the mania is broken.